Abstract

Previously, we had isolated by transposon mutagenesis a Legionella pneumophila mutant that appeared defective for intracellular iron acquisition. While sequencing in the proximity of the mini-Tn10 insertion, we found a locus that had a predicted protein product with strong similarity to PilB from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. PilB is a component of the type II secretory pathway, which is required for the assembly of type IV pili. Consequently, the locus was cloned and sequenced. Within this 4-kb region were three genes that appeared to be organized in an operon and encoded homologs of P. aeruginosa PilB, PilC, and PilD, proteins essential for pilus production and type II protein secretion. Northern blot analysis identified a transcript large enough to include all three genes and showed a substantial increase in expression of this operon when L. pneumophila was grown at 30°C as opposed to 37°C. The latter observation was then correlated with an increase in piliation when bacteria were grown at the lower temperature. Southern hybridization analysis indicated that the pilB locus was conserved within L. pneumophila serogroups and other Legionella species. These data represent the first isolation of type II secretory genes from an intracellular parasite and indicate that the legionellae express temperature-regulated type IV pili.

The gram-negative bacterium Legionella pneumophila causes a potentially fatal pneumonia known as Legionnaires’ disease (7, 20). This organism normally exists in freshwater ecosystems, either free living within biofilms or as an intracellular parasite of protozoa (23). In order for L. pneumophila to cause disease within humans, contaminated aerosols must be inhaled into the lung, where alveolar macrophages serve as the primary sites of bacterial replication (7). Interestingly, alveolar type I and type II epithelial cells are infected in vitro by this bacterium, suggesting a secondary mechanism for survival and spread of the pathogen within its human host (10, 28). Unfortunately, our understanding of L. pneumophila pathogenesis is still rather minimal. However, a number of known or candidate virulence factors have been identified. For example, L. pneumophila possesses flagella and pili which may aid in adherence of the bacteria to host cells (41). Furthermore, several loci, including mip, dot, and icm, potentiate intracellular survival and replication (3, 5, 9). Finally, a variety of excreted toxins and enzymes, such as proteases and phospholipases, may promote tissue destruction and bacterial spread (7).

The focus of our recent efforts has been to identify bacterial systems which facilitate the intracellular acquisition of nutrients such as iron (17, 18, 24, 33, 36). As one approach toward identifying these virulence factors, we randomly mutagenized L. pneumophila 130b (serogroup 1) with mini-Tn10 and screened for mutants with deficiencies in both iron uptake (e.g., resistance to streptonigrin) and growth within U937 cells, a human macrophage-like cell line (36). Seventeen mutants appeared defective for iron uptake, and six of these had infectivity defects. While the genetic basis of the defect in one of these mutants (i.e., NU218) was being determined, an operon (pilBCD) containing genes involved in pilin biosynthesis and type II protein secretion was discovered and characterized.

To determine the genetic loci involved in L. pneumophila iron acquisition, we employed inverse PCR to identify sequences near each of the mini-Tn10 insertions in our iron uptake mutants (31). More specifically, 5 μg of genomic DNA was digested with HindIII, an enzyme which cuts once within the mini-Tn10, and then the restricted DNA was circularized with T4 DNA ligase overnight at 15°C. After ethanol precipitation of the ligated molecules, PCR products were generated with primers (5′-TGATTTTGATGACGAGCG and 5′-GTGACGACTGAATCCGGT) that recognize sequences on either side of the transposon’s HindIII site as well as a primer (5′-CCTTAACTTAATGATTTTTAC) specific for a sequence in the transposon’s inverted repeats. For each mutant, there was the potential to obtain two PCR products, enabling sequencing of the regions immediately surrounding the transposon as well as the DNA flanking the distal HindIII sites. The conditions utilized for PCR were 1.5 min at 95°C and 1 min at 47°C, followed by 3 min at 72°C, with 30 cycles and 1.25 U of Taq polymerase added in a total reaction volume of 50 μl. To prepare the PCR products for sequencing, approximately 100 ng of PCR product was incubated with 2 U of alkaline phosphatase and 1 U of exonuclease I for 15 min at 37°C, followed by enzyme inactivation at 80°C for 15 min. PCR products and plasmids were sequenced with the Perkin-Elmer sequencing kit according to the manufacturer’s specifications (Foster City, Calif.).

While sequencing a region more than 1 kb away from the mini-Tn10 insertion in the mutant NU218, we found sequences encoding a predicted protein with strong similarity to PilB of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. PilB and its homologs in other bacteria are components of type II protein secretion systems that are required for the assembly of type IV pili (22, 29, 35). The importance of type IV pili for mediating the attachment of P. aeruginosa and other pathogens to epithelial cells has been well documented (14, 15, 26, 46). Early studies by Rodgers and colleagues had detected pili in L. pneumophila, but the nature of these structures and the genes and proteins involved in their biosynthesis have remained elusive (40, 41). In many species, the gene encoding the PilB homolog is adjacent to the gene for the type IV pilus subunit as well as other genes involved in pilin biogenesis (29, 35). One of these nearby genes, encoding the prepilin peptidase PilD in P. aeruginosa, is also involved, albeit indirectly, in the export of toxins and enzymes (25). We therefore sought to confirm the existence of a Legionella pilB-like gene and to identify other genes in its vicinity that might contribute to the biosynthesis of pili and/or type II protein secretion.

To isolate clones containing the putative pilB homolog, the 1.8-kb PCR product generated from NU218 was labeled with digoxigenin (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, Ind.) and used to probe genomic libraries of strain 130b (1, 17). Southern blots confirmed the presence of the gene within four different cosmids and one plasmid (data not shown). To facilitate sequencing of this locus, the 5-kb segment of Legionella DNA from the recombinant plasmid was subcloned into pSU2719 (4, 27), and the resulting plasmid, pML218, was subjected to unidirectional deletion with exonuclease III (13). To help determine sequences downstream of the putative pilB analog, a 6-kb BglII fragment from one of the cosmids (i.e., C5) was subcloned into pSU2719, yielding pML219.

The 4,259-bp region that was sequenced had three open reading frames (ORFs) which were predicted to encode products with significant similarity to proteins involved in type II protein secretion and pilin biogenesis (Fig. 1). The first ORF was 1,723 bp in length, and the deduced amino acid sequence predicted a 62-kDa protein with 52% identity and 72% similarity to P. aeruginosa PilB. This predicted product was also similar in terms of sequence and size to PilB analogs in Aeromonas hydrophila, Dichelobacter nodosus, and Neisseria gonorrhoeae, among others, and possessed the highly conserved Walker sequence, an ATP-binding motif found in PilB-like proteins (Fig. 2) (50). Although the exact cellular location and function of PilB are unknown, the protein is believed to be present at the cytoplasmic face of the inner membrane, where its nucleotide-binding domain may provide energy for the introduction of prepilin into the inner membrane (46). Due to the considerable similarity of the predicted protein to P. aeruginosa PilB, we designated the first ORF as the L. pneumophila pilB gene. Immediately downstream of L. pneumophila pilB was an ORF predicted to encode a 45-kDa protein which had 50% identity and 72% similarity to P. aeruginosa PilC, as well as comparable similarity to PilC homologs in other species (data not shown). As was the case for PilB, mutational analysis had determined that PilC is required for pilus expression (37, 49). More specifically, PilC-like proteins, because of their putative transmembrane domains, are believed to be anchored within the inner membrane where they may facilitate pilin translocation (46). Our designation for the second L. pneumophila ORF was pilC. The region downstream of pilC revealed a third ORF predicted to encode a 33-kDa protein with significant similarity to P. aeruginosa PilD and PilD homologs in other bacteria (Fig. 3). PilD is a bifunctional enzyme which cleaves prepilin and N methylates the first residue of the resultant mature pilin (25). Furthermore, this peptidase also processes the secreted prepilin-like proteins (XcpT, XcpU, XcpV, and XcpW) that are required for the terminal branch of type II protein secretion in P. aeruginosa (30). Thus, PilD, unlike PilB and PilC, has the additional function of contributing to the export of important toxins and enzymes, such as exotoxin A, phospholipase C, and elastase (30, 47). Although clearly significant, the sequence homology between L. pneumophila PilD and P. aeruginosa PilD (43% identity and 58% similarity) is less than that observed between L. pneumophila PilB or PilC and its respective homologs (Fig. 3). However, the L. pneumophila protein did contain a conserved tetracysteine domain which is thought to be important for the correct folding of the peptidase (Fig. 3) (38, 45). Overall, the G+C percentage of the L. pneumophila pilB, pilC, and pilD genes was 36.6%. This value is fairly close to the 39% G+C content associated with the L. pneumophila genome (6), suggesting that this locus is not a recent acquisition (43). Although we have not confirmed that these three ORFs express functional products, these sequence data do indicate that L. pneumophila contains a set of genes well known to participate in type II protein secretion. Furthermore, they represent the first recorded instance of a type II secretory system in an intracellular parasite. Given that L. pneumophila has pilBCD analogs, we strongly suspect that L. pneumophila also possesses the other components of the type II secretory system. Finally, the discovery of pilB, pilC, and pilD in strain 130b strongly suggested that L. pneumophila expresses type IV pili.

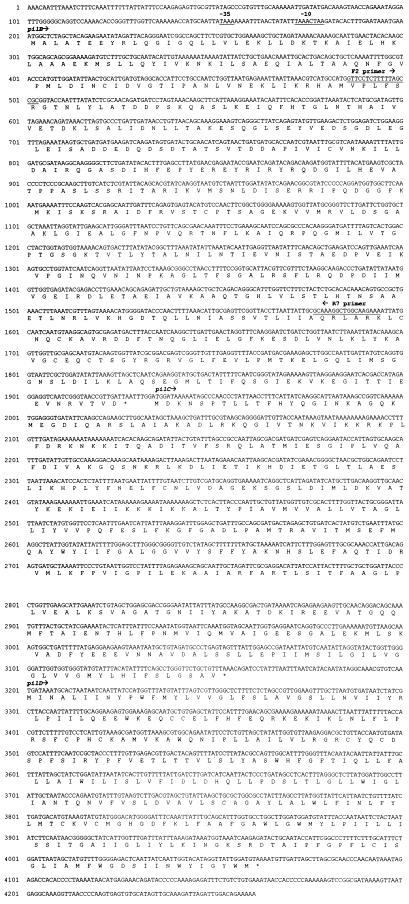

FIG. 1.

Nucleotide sequence of the L. pneumophila pilBCD genes. The deduced amino acid sequences of the three ORFs and the termination codons (∗) are indicated. The direction of transcription-translation of each ORF is indicated by a horizontal arrow. The possible binding sites for the alternative ς28 factor are indicated by the −35 and −10 designations. Although Northern blot analysis indicated otherwise (see below), no transcriptional terminator was evident at the end of the pilBCD locus. The locations of the F2 and R7 primers used to prepare a pilB-specific probe are also indicated. The sequence between nucleotides 1 and 3140 was obtained from analysis of the pML218 insert, whereas the sequence from nucleotides 689 to 4259 was from the pML219 insert. Double-stranded sequence data were compiled with Gene Runner (Hastings Software, Inc., Hastings, N.Y.).

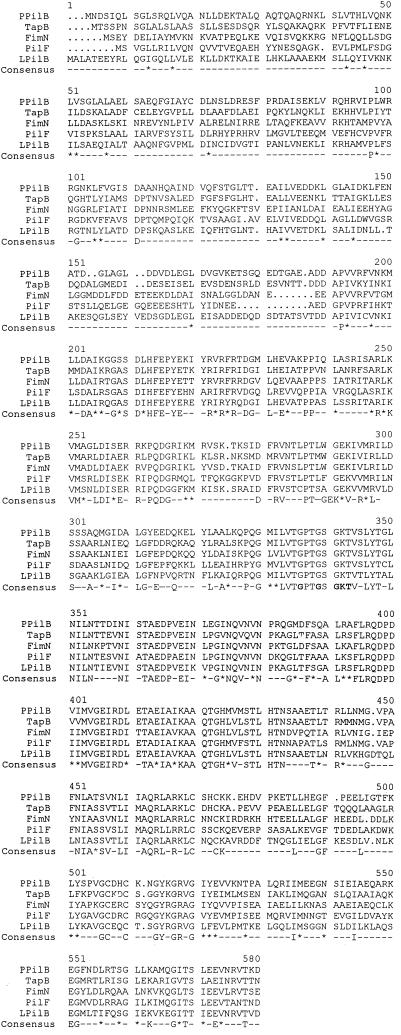

FIG. 2.

Alignment of the deduced amino acid sequence of the L. pneumophila PilB protein (LPilB) with homologs from P. aeruginosa (PPilB), A. hydrophila (TapB), D. nodosus (FimN), and N. gonorrhoeae (PilF). The positions and identities of amino acids common to all five proteins are indicated on the last line by the conserved letter, whereas conservative amino acid changes are indicated on this line by asterisks. The position of the conserved nucleotide-binding domain (Walker sequence) is in boldface within the consensus sequence. Other species expressing PilB homologs include Xanthomonas campestris, enteropathogenic E. coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Vibrio cholerae (data not shown). The sequences for all PilB analogs were obtained from GenBank at NCBI. For protein alignments, we used programs within the Genetics Computer Group Sequencing Analysis Software package (GCG, Madison, Wis.).

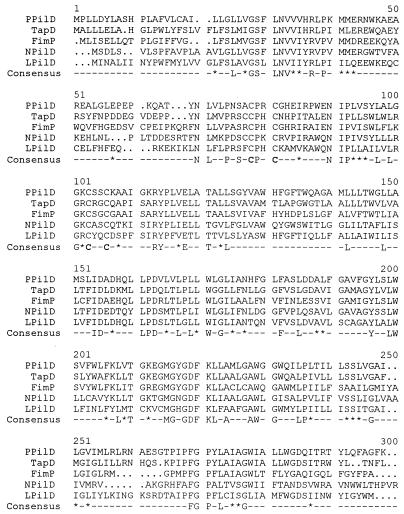

FIG. 3.

Alignment of the deduced amino acid sequence of the L. pneumophila PilD protein (LPilD) with homologs from P. aeruginosa (PPilD), A. hydrophila (TapD), D. nodosus (FimP), and N. gonorrhoeae (NPilD). The positions and identities of amino acids common to all five proteins are indicated on the last line by the conserved letter, whereas conservative amino acid changes are indicated on this line by asterisks. The conserved tetracysteine domain is highlighted in boldface within the consensus sequence. Other species expressing L. pneumophila PilD homologs include Xanthomonas campestris, enteropathogenic E. coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Vibrio cholerae (data not shown). The sequences for all PilD analogs were obtained from GenBank at NCBI. For protein alignments, we used programs within the Genetics Computer Group Sequencing Analysis Software package (GCG).

The genes required for pilin secretion are often adjacent to the type IV pilin gene. For example, in P. aeruginosa, pilA is located 192 bp upstream from pilB (29). Therefore, in an attempt to locate an L. pneumophila pilin gene, we sequenced the regions directly upstream of pilB (2 kb) and downstream of pilD (300 bp). The DNA sequences flanking pilB and pilD did not contain the pilin gene and did not have significant similarity to genes in the GenBank database (Fig. 1 and data not shown). However, Stone and Abu Kwaik report in this issue the discovery of an L. pneumophila 130b gene (pilEL) that is required for the production of long pili and whose predicted product has strong homology to type IV pilins (44). Using a digoxigenin-labeled, 2-kb ClaI fragment from pBJ120 which contains pilEL (44), we probed a Southern blot containing DNAs from all of our pilBCD plasmids and cosmids as well as a 130b control. No hybridization was observed except for one band in strain 130b (data not shown), indicating that there are at least two distinct regions of the L. pneumophila chromosome involved in type IV pilin biosynthesis. The arrangement of the L. pneumophila pilin biosynthetic genes thus appears to be most like that of D. nodosus (Fig. 4). However, chromosomal mapping and transcriptional analysis of both the pilBCD locus and pilEL will be necessary to establish how similar the organizations of pilin biosynthetic genes are in these two pathogens.

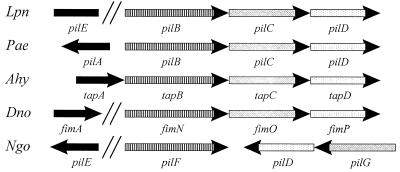

FIG. 4.

Organization of type II secretory/pilus biogenesis genes in L. pneumophila (Lpn), P. aeruginosa (Pae), A. hydrophila (Ahy), D. nodosus (Dno), and N. gonorrhoeae (Ngo) (19, 22, 29, 35). Note that the orientation of the Lpn pilin gene with respect to the Lpn pilBCD operon is unknown. Common shading of the bars indicates homology between the proteins.

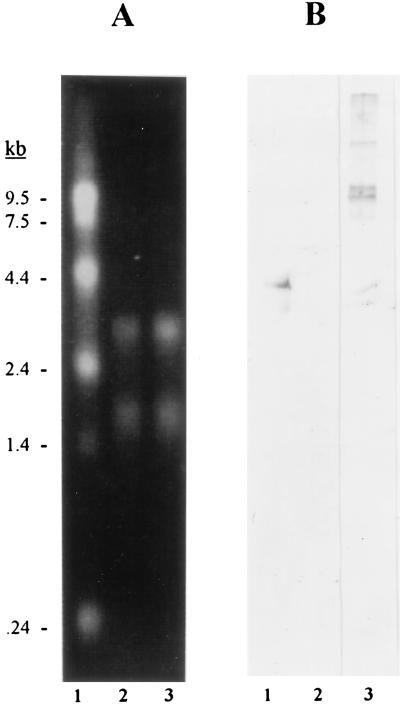

In other organisms, the pilB-, pilC-, and pilD-like genes are often arranged in an operon (Fig. 4). In L. pneumophila, pilC began only 8 bp past the end of pilB, and pilD followed only 48 bp past pilC, suggesting that these three ORFs are also cotranscribed (Fig. 1). To confirm this hypothesis, we hybridized RNA isolated from L. pneumophila by using the Trizol reagent (Gibco-BRL) with a pilB-specific probe (Fig. 1). Since the legionellae exist in aquatic environments as well as in the mammalian lung, and since the expression of their flagella is greater at 30°C than at 37°C (34), we assessed the expression of pilB in 130b grown at both 30 and 37°C. The Northern blot revealed a transcript of sufficient size (i.e., approximately 4 kb) to include all three ORFs, but only from the bacteria grown at 30°C (Fig. 5). No transcripts were detected in the bacteria grown at 37°C. To determine whether low-level transcription occurred at 37°C, we used a more sensitive reverse transcriptase PCR assay. Briefly, total RNA was first treated with RNase-free DNase for 2 h at 37°C. The RNA was then precipitated, and the DNase treatment was repeated three times until control PCRs indicated no residual DNA contamination. After addition of random hexamers, reverse transcriptase, and RNase inhibitors to 1 μg of L. pneumophila RNA, the reaction mixtures were incubated at 42°C for 1 h, followed by 10 min at 94°C. With the cDNA as template, PCR was performed with pilB-specific primers (Fig. 1). We detected the expected 1,048-bp PCR product, indicating that pilB mRNA exists within bacteria grown at 37°C (data not shown). Taken together, these data suggest that, although the L. pneumophila pilBCD genes are similar both in their predicted products and in their organization to type II secretory genes in other gram-negative bacteria, they are unique in terms of their regulation. The difference between the levels of pilB expression at 30 and 37°C suggests that pilBCD is regulated in a manner similar to that observed with the L. pneumophila flagellin gene, i.e., transcriptional control by the alternative ς28-like RpoF factor (16). In support of this notion, the promoter region of the pilBCD operon appears to possess some elements of the ς28 consensus sequence (Fig. 1).

FIG. 5.

Temperature-dependent expression of pilBCD. Five micrograms of bacterial RNA along with RNA size markers (Gibco-BRL) was electrophoresed through a 1% agarose-formaldehyde gel and then transferred onto nitrocellulose. After baking, the blot was incubated overnight at 50°C with a digoxigenin-labeled probe in the manufacturer’s recommended hybridization solution (Boehringer Mannheim). After high-stringency washing, the hybridized probe was detected colorimetrically. Duplicate samples were stained with ethidium bromide to visualize the integrity and concentration of RNA. (A) Ethidium bromide-stained agarose-formaldehyde gel containing RNA markers (lane 1) and RNA from L. pneumophila grown at 30°C (lane 2) and 37°C (lane 3). Note that the 30°C sample contains no more, and likely less, RNA than the 37°C sample. (B) Northern blot hybridized with the pilB-specific probe. Samples include RNA isolated from L. pneumophila grown at 30°C (lane 1) and 37°C (lane 2) and E. coli XL1Blue (pML218) grown at 37°C (lane 3). The larger bands evident in lane 3, panel B, are most likely due to transcripts initiating from a vector promoter(s).

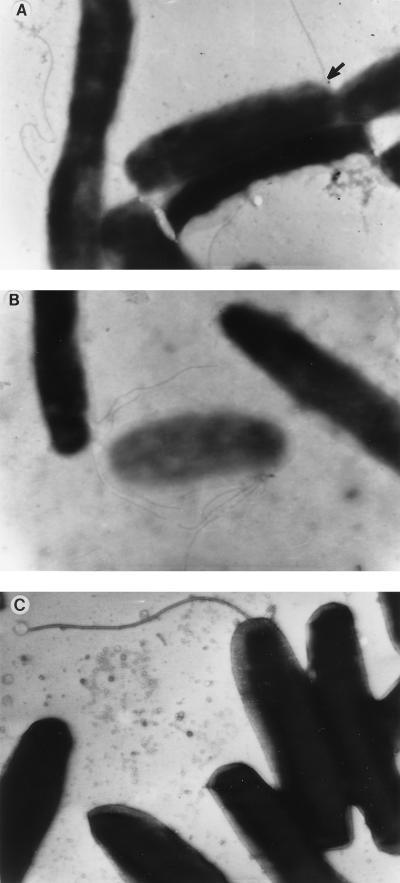

The increase in the level of pilBCD transcripts at 30°C suggested that piliation in L. pneumophila is also controlled by temperature. To address this hypothesis, we grew strain 130b on buffered charcoal yeast extract agar for 72 h at either 30 or 37°C and then examined bacteria by electron microscopy. To visualize pili on the surface of L. pneumophila, we employed a slight variation of the method described by Ruffolo et al. (42). Briefly, 100 μl of sterile phosphate-buffered saline was placed on isolated colonies of strain 130b, and then Formvar-coated copper grids (Ladd Industries, Burlington, Vt.) were placed gently onto the wetted colonies. After 2 min, the grids were removed, and excess saline was wicked off with Whatman no. 3 filter paper. Bacteria adherent to the grid were stained with 10 μl of 1% phosphotungstic acid (PTA; Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) for 1 min, after which the PTA was carefully removed with filter paper, and the grids were allowed to air dry for several minutes. Finally, stained bacteria were visualized on a JEOL JEM-100 CxII transmission electron microscope at 60 kV. When grown at 30°C, on average 5 to 10% of bacteria had pili, with many unattached pili also present on the grids, but on rare occasions up to 50% of the bacteria could be seen to possess pili. Typically, we saw only one pilus per cell that was of a length, diameter, and position comparable to those observed by others (40, 44) (Fig. 6A). Bacteria with multiple pili radiating from their surfaces were also noticed (Fig. 6B). It is possible that these multiple pilin strands can form a cohesive bundled pilus as seen with the bundle-forming pilus of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (12). In contrast, we did not see pili on bacteria grown at 37°C, and only rarely could a flagellum be found (Fig. 6C). This temperature-dependent expression of pili was observed in three independent experiments, with hundreds of bacteria being examined on each occasion. The lower incidence of piliation at 37°C in our study compared to others is likely due to differences in growth conditions. For example, Rodgers et al. observed piliated L. pneumophila when strains were grown on enriched blood agar (41). Similarly, Stone and Abu Kwaik examined strain 130b after growth in static buffered yeast extract broth, a method differing from ours in O2 concentration, the presence of agar, and the general stage of bacterial growth (44). Currently, it is unknown whether the temperature-induced alteration in piliation results simply from the observed changes in pilBCD transcription or also requires changes in pilEL expression. Other temperature-regulated pili include the type IV bundle-forming pilus and the M pilus of E. coli (21, 48). Whereas the M pilus, like the L. pneumophila pilus, is minimally expressed at 37°C, the bundle-forming pilus is hyperexpressed at the elevated temperature. Although temperature-regulated piliation is not novel, this is, to our knowledge, the first demonstration of temperature-dependent expression of type II secretory genes.

FIG. 6.

Temperature-dependent piliation of L. pneumophila. Bacteria were grown at either 30°C (A and B) or 37°C (C), stained with PTA, and examined by transmission electron microscopy. (A) Three different bacteria grown at 30°C possess a single pilus. One of the pilus structures may represent the bundling of two or more individual fibers (see arrow for possible fusion point). (B) Multiple pili are seen radiating from two different bacteria also grown at 30°C. (C) One of the bacteria grown at 37°C has a flagellum, but none of the cells have pili. Note the significantly larger diameter of the flagellum in panel C in comparison to the thinner pili in the first two panels. All electron micrographs are at a magnification of ca. ×17,000.

In addition to L. pneumophila, the Legionella genus contains 40 other species, with half of these being associated with disease (2). Pili have been detected, but not classified, in strains of L. micdadei, L. birminghamensis, L. gormanii, and L. jamestowniensis as well as strains from L. pneumophila serogroups 1 to 6, but not in a strain of L. longbeachae (40). Thus, we tested various L. pneumophila serogroups and Legionella species for hybridization with the pilB-specific probe (Table 1). L. pneumophila strains representing serogroups 2 to 5 and 8 to 14 hybridized under high-stringency conditions (permitting ca. 10% base pair mismatch) with the probe, giving a single band that varied in size (data not shown). Similarly, 14 other Legionella species tested hybridized with pilB DNA, albeit under low-stringency conditions (permitting ca. 30% base pair mismatch [data not shown]). With the exception of L. israelensis, the intensity of the bands from the various species was noticeably weaker than that from L. pneumophila, despite equivalent amounts of genomic DNA being analyzed for each sample. Nevertheless, these data indicate that pilBCD is conserved in the Legionella genus and suggest that many legionellae have the genetic potential to express type IV pili. Finally, since L. pneumophila as well as other Legionella species secretes enzymes and toxins (11), it is likely that the pilBCD operon facilitates Legionella growth and pathogenesis in multiple ways.

TABLE 1.

Legionella strainsa used in this study

| Sp. | Strain | Serogroup | Implicated in disease |

|---|---|---|---|

| L. pneumophila | 130b (Wadsworth) | 1 | Yes |

| L. pneumophila | ATCC 33154 | 2 | Yes |

| L. pneumophila | ATCC 33155 | 3 | Yes |

| L. pneumophila | ATCC 33156 | 4 | Yes |

| L. pneumophila | ATCC 33216 | 5 | Yes |

| L. pneumophila | ATCC 35096 | 8 | Yes |

| L. pneumophila | MDPHb | 9 | Yes |

| L. pneumophila | MDPHb | 10 | Yes |

| L. pneumophila | MDPHb | 11 | Yes |

| L. pneumophila | MDPHb | 12 | Yes |

| L. pneumophila | B2A3105 | 13 | Yes |

| L. pneumophila | 1169-MN-H | 14 | Yes |

| L. birminghamensis | 1407-AL-H | Yes | |

| L. erythra | SE-32A | No | |

| L. gormanii | ATCC 33297 | Yes | |

| L. feeleii | WO-44C | Yes | |

| L. hackeliae | Lansing 2 | Yes | |

| L. israelensis | Bercovier 4 | No | |

| L. jamestowniensis | JA-26 | No | |

| L. longbeachae | ATCC 33462 | Yes | |

| L. micdadei | Rivera | Yes | |

| L. oakridgensis | OR-10 | Yes | |

| L. parisiensis | PF-209 | Yes | |

| L. sainthelensi | Mount St. Helens 4 | Yes | |

| L. santicrucis | SC-63 | No | |

| L. spiritensis | MSH-9 | No |

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The L. pneumophila pilBCD sequence is deposited in the GenBank database at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) under accession no. AF038655.

Acknowledgments

We thank Barbara Stone and Yousef Abu Kwaik for sharing their data and pilEL clone prior to publication. We also thank Joe Dillard, Cynthia Long, Carmel Ruffolo, and Mark Strom for technical assistance and helpful discussions and Mark McClain and N. Cary Engleberg for the generous donation of the 130b cosmid library.

M.R.L. was supported, in part, by NIH training grant ES07284. Overall, this work was funded by grant AI34937 from the NIH.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arroyo J, Hurley M C, Wolf M, McClain M S, Eisenstein B I, Engleberg N C. Shuttle mutagenesis of Legionella pneumophila: identification of a gene associated with host cell cytopathicity. Infect Immun. 1994;62:4075–4080. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.9.4075-4080.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benson R F, Thacker W L, Daneshvar M I, Brenner D J. Legionella waltersii sp. nov. and an unnamed Legionella genomospecies isolated from water in Australia. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1996;46:631–634. doi: 10.1099/00207713-46-3-631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berger K H, Merriam J J, Isberg R R. Altered intracellular targeting properties associated with mutations in Legionella pneumophila dotA gene. Mol Microbiol. 1994;14:809–822. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Birnboim H C. A rapid alkaline extraction method for the isolation of plasmid DNA. Methods Enzymol. 1983;100:243–255. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(83)00059-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brand B C, Sadosky A B, Shuman H A. The Legionella pneumophila icm locus: a set of genes required for intracellular multiplication in human macrophages. Mol Microbiol. 1994;14:797–808. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brenner D J, Steigerwalt A G, Weaver R E, McDade J E, Feeley J C, Mandel M. Classification of the Legionnaires’ disease bacterium: an interim report. Curr Microbiol. 1978;1:7–10. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cianciotto N, Eisenstein B I, Engleberg N C, Shuman H. Genetics and molecular pathogenesis of Legionella pneumophila, an intracellular parasite of macrophages. Mol Biol Med. 1989;6:409–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cianciotto N P, Bangsborg J M, Eisenstein B I, Engleberg N C. Identification of mip-like genes in the genus Legionella. Infect Immun. 1990;58:2912–2918. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.9.2912-2918.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cianciotto N P, Fields B S. Legionella pneumophila mip gene potentiates intracellular infection of protozoa and human macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:5188–5191. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.11.5188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cianciotto N P, Stamos J K, Kamp D W. Infectivity of Legionella pneumophila mip mutant for alveolar epithelial cells. Curr Microbiol. 1995;30:247–250. doi: 10.1007/BF00293641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dowling J N, Saha A K, Glew R H. Virulence factors of the family Legionellaceae. Microbiol Rev. 1992;56:32–60. doi: 10.1128/mr.56.1.32-60.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giron J A, Ho A S Y, Schoolnik G K. An inducible bundle-forming pilus of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Science. 1991;254:710–713. doi: 10.1126/science.1683004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guo L H, Wu R. New rapid methods for DNA sequencing based on exonuclease III digestion followed by repair synthesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 1982;10:2065–2084. doi: 10.1093/nar/10.6.2065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hahn H P. The type-4 pilus is the major virulence-associated adhesin of Pseudomonas aeruginosa—a review. Gene. 1997;192:99–108. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00116-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heckels J E. Structure and function of pili of pathogenic Neisseria species. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1989;2:S66–S73. doi: 10.1128/cmr.2.suppl.s66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heuner K, Bender-Beck L, Brand B C, Luck P C, Mann K, Marre R, Ott M, Hacker J. Cloning and genetic characterization of the flagellum subunit gene (flaA) of Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2499–2507. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.7.2499-2507.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hickey E K, Cianciotto N P. Cloning and sequencing of the Legionella pneumophila fur gene. Gene. 1994;143:117–121. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90615-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hickey E K, Cianciotto N P. An iron- and Fur-repressed Legionella pneumophila gene that promotes intracellular infection and encodes a protein with similarity to the Escherichia coli aerobactin synthetases. Infect Immun. 1997;65:133–143. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.1.133-143.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hobbs M, Dalrymple B P, Cox P T, Livingstone S P, Delaney S F, Mattick J S. Organization of the fimbrial gene region of Bacteroides nodosus: class I and class II strains. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:543–560. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb00726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Horwitz M A. Interactions between macrophages and Legionella pneumophila. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1992;181:265–282. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-77377-8_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karste G, Adler K, Tschape H. Temperature dependence of M pilus formation as demonstrated by electron microscopy. J Basic Microbiol. 1987;27:225–228. doi: 10.1002/jobm.3620270414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lauer P, Albertson N H, Koomey M. Conservation of genes encoding components of a type IV pilus assembly/two-step protein export pathway in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:357–368. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee J V, West A A. Survival and growth of Legionella species in the environment. J Appl Bacteriol Symp Suppl. 1991;70:121S–129S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liles M R, Cianciotto N P. Absence of siderophore-like activity in Legionella pneumophila supernatants. Infect Immun. 1996;64:1873–1875. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.5.1873-1875.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lory S, Strom M S. Structure-function relationship of type-IV prepilin peptidase of Pseudomonas aeruginosa—a review. Gene. 1997;192:117–121. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00830-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manning P A. The tcp gene cluster of Vibrio cholerae. Gene. 1997;192:63–70. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00036-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martinez E, Bartolome B, de la Cruz F. pACYC184-derived cloning vectors containing the multiple cloning site and lacZ alpha reporter gene of pUC8/9 and pUC18/19 plasmids. Gene. 1988;68:159–162. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90608-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mody C H, Paine III R, Shahrabadi M S, Simon R H, Pearlman E, Eisenstein B I, Toews G B. Legionella pneumophila replicates within rat alveolar epithelial cells. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:1138–1145. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.5.1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nunn D, Bergman S, Lory S. Products of three accessory genes, pilB, pilC, and pilD, are required for biogenesis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa pili. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:2911–2919. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.6.2911-2919.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nunn D N, Lory S. Components of the protein-excretion apparatus of Pseudomonas aeruginosa are processed by the type IV prepilin peptidase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:47–51. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.1.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ochman H, Gerber A S, Hartl D L. Genetic applications of an inverse PCR. Genetics. 1988;120:621–623. doi: 10.1093/genetics/120.3.621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O’Connell W A, Bangsburg J M, Cianciotto N P. Characterization of a Legionella micdadei mip mutant. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2840–2845. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.8.2840-2845.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O’Connell W A, Hickey E K, Cianciotto N P. A Legionella pneumophila gene that promotes hemin binding. Infect Immun. 1996;64:842–848. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.3.842-848.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ott M, Messner J, Heesemann R, Marre R, Hacker J. Temperature-dependent expression of flagella in Legionella. J Gen Microbiol. 1991;137:1955–1961. doi: 10.1099/00221287-137-8-1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pepe C M, Eklund M W, Strom M S. Cloning of an Aeromonas hydrophila type IV pilus biogenesis cluster: complementation of pilus assembly functions and characterization of a type IV leader peptidase/N-methyltransferase required for extracellular protein secretion. Mol Microbiol. 1996;19:857–869. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.431958.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pope C D, O’Connell W A, Cianciotto N P. Legionella pneumophila mutants that are defective for iron acquisition and assimilation and intracellular infection. Infect Immun. 1996;64:629–636. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.2.629-636.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Possot O, d’Enfert C, Reyss I, Pugsley A P. Pullulanase secretion in Escherichia coli K-12 requires a cytoplasmic protein and a putative polytopic cytoplasmic membrane protein. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:95–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb00841.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Possot O M, Pugsley A P. The conserved tetracysteine motif in the general secretory pathway component PulE is required for efficient pullulanase secretion. Gene. 1997;192:45–50. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00009-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Presti F L, Riffard S, Vandenesch F, Reyrolle M, Ronco E, Ichai P, Etienne J. The first clinical isolate of Legionella parisiensis, from a liver transplant patient with pneumonia. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1706–1709. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.7.1706-1709.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rodgers F G. Morphology of Legionella. In: Katz S M, editor. Legionellosis. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press; 1985. pp. 39–82. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rodgers F G, Greaves P W, Macrae A D, Lewis M J. Electron microscopic evidence of flagella and pili on Legionella pneumophila. J Clin Pathol. 1980;33:1184–1188. doi: 10.1136/jcp.33.12.1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ruffolo C G, Tennent J M, Michalski W P, Adler B. Identification, purification, and characterization of the type 4 fimbriae of Pasteurella multocida. Infect Immun. 1997;65:339–343. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.1.339-343.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Spangenberg C, Fislage R, Romling U, Tummler B. Disrespectful type IV pilins. Mol Microbiol. 1997;25:203–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stone B, Abu Kwaik Y. Expression of multiple pili by Legionella pneumophila: identification and characterization of a type IV pilin gene and its role in adherence to mammalian and protozoan cells. Infect Immun. 1998;66:1768–1775. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.4.1768-1775.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Strom M S, Bergman P, Lory S. Identification of active-site cysteines in the conserved domain of PilD, the bifunctional type IV pilin leader peptidase/N-methyltransferase of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:15788–15794. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Strom M S, Lory S. Structure-function and biogenesis of the type IV pili. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1993;47:565–596. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.47.100193.003025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Strom M S, Nunn D, Lory S. Multiple roles of the pilus biogenesis protein PilD: involvement of PilD in excretion of enzymes from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:1175–1180. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.3.1175-1180.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tobe T, Schoolnik G K, Sohel I, Bustamante V H, Puente J L. Cloning and characterization of bfpTVW, genes required for the transcriptional activation of bfpA in enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1997;21:963–975. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.531415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tonjum T, Freitag N E, Namork E, Koomey M. Identification and characterization of pilG, a highly conserved pilus-assembly gene in pathogenic Neisseria. Mol Microbiol. 1995;16:451–464. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Turner L R, Lara J C, Nunn D N, Lory S. Mutations in the consensus ATP-binding sites of XcpR and PilB eliminate extracellular protein secretion and pilus biogenesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:4962–4969. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.16.4962-4969.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]