Abstract

Practical relevance:

More cats are travelling by air every year; however, air travel involves several common causes of stress for cats, such as environmental changes and a lack of control and predictability. The use of a multimodal stress management protocol for all stages of the relocation process, including appropriate and effective anxiolytic medication where necessary, is therefore important in order to safeguard the cat’s welfare while travelling.

Clinical challenges:

Cats may be presented to veterinarians for the purpose of preparing them and/or their documentation for air travel. Maintaining and protecting a cat’s physical, mental and emotional health in a stressful environment, while subjected to likely unfamiliar sights, noises, smells and the movement of the aircraft, and additionally dealing with international legislation, regulations and documents, can pose a complex challenge to veterinarians.

Aims:

This review describes the importance of stress management during air travel for cats, aims to raise awareness about the often poorly understood challenges involved, and outlines effective and airline-compliant stress management modalities. While the discussion is focused on air travel specifically, the stress management methods described can be applied to all types of longer distance travel, such as a long road trip or a ferry crossing, as well as a stay in a holiday home.

Evidence base:

There are currently no studies specifically on air travel in cats and, similarly, there are also limited data on air travel in other species. Many of the recommendations made in this review are therefore based on the authors’ extensive experience of preparing pets for travel, supported by published data when available.

Keywords: Air travel, travel, stress, management

Introduction

Pet travel has increased by 19% in the past decade and over 2 million pets and other live animals are transported by air every year in the USA alone. 1 Cats have been reported to make up 22% of all pet travellers annually. 2 While there is no research-based evidence for cats, research in other species and current knowledge about stress in cats indicate that air transportation is likely to be stressful for them. A study investigating physiological signs and behaviour of dogs during air transport concluded that air transportation is stressful for this species. 3 Further studies have shown that horses experience a sharp increase in heart rate and changes in behavioural activities during air transport, especially during the transitional stages such as the aircraft ascending and descending, 4 and that in two Giant Pandas transported by air from China to the USA, urinary cortisol was highest during the time of the flight compared with the remainder of the 30-day period post-transport. 5

For cats, air transportation involves some of the main causes of stress, suggesting that feline welfare may also be negatively impacted. 6

Understanding and recognising stress related to air travel

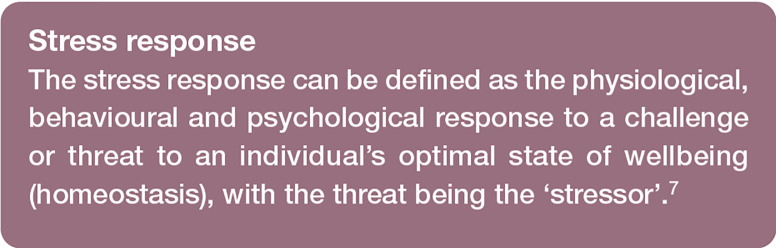

Some of the main causes of stress in cats include environmental changes, such as displacement from territory (eg, when moving to a new house), and a lack of control and predictability, 8 both of which occur during air transportation. Further stressors that cats encounter in relation to air travel can be found in Figure 1.9,10

Figure 1.

Air transportation involves a number of causes of stress for cats. If several of these affect the cat at the same time, the stress response will be much greater than if the animal was exposed to one stressor only

Stressors have additive effects, which means that when several stressors impinge upon the animal at the same time, the resulting stress response will be much greater than if the animal was exposed to one stressor only - a phenomenon known as ‘stressor-stacking’ or ‘trigger-stacking’. The first response to this is a behavioural one. If the animal finds itself in a situation where their ability to perform the behavioural response is limited or thwarted (eg, by confinement), the animal’s second line of defence is activation of the autonomic nervous system. 11

When the stress load is perceived to exceed the coping ability of the individual, this can lead to distress - a negative state of mental or emotional strain resulting from adverse or potentially over-demanding circumstances. 6 A cat’s ability to respond appropriately to a stressor will profoundly influence which emotion(s) it experiences and whether distress will develop. Distinct emotional responses may include anxiety/fear, frustration and pain. 12

When the stress response activates the autonomic nervous system, it affects a diverse number of biological systems including the cardiovascular and respiratory systems, the gastrointestinal tract, urinary tract, exocrine glands and the adrenal glands. 11 Activation of these systems leads to physiological responses, such as increased heart rate, blood pressure and gastrointestinal activity, extremes of which are undesirable and particularly problematic during air transportation as they may lead to physiological decompensation during a time when the cat is not under direct supervision, longer term tissue and organ injury (especially eyes, brain, kidneys and heart) 13 and soiling of the travel carrier.

Recognising stress in cats

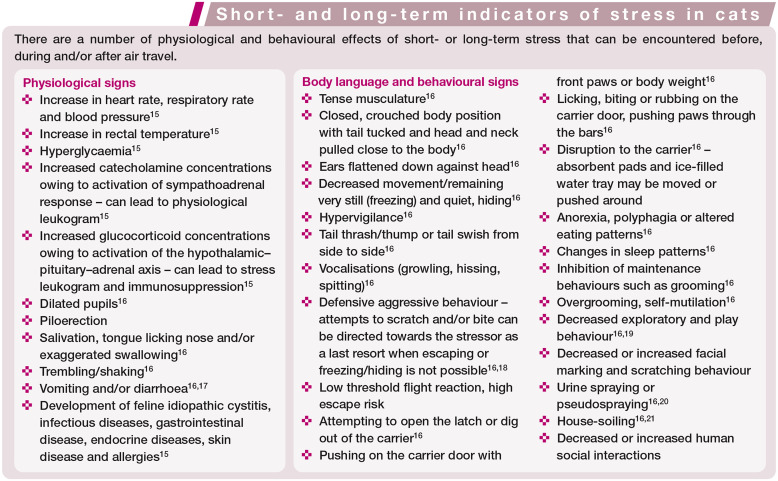

Although cats are predators by nature, when restrained or confined they can exhibit many behaviours characteristic of a prey species, including flight reactions to noises and unfamiliar stimuli, avoidance responses to unfamiliar individuals and defensive reactions. When feeling threatened, cats may try to escape, freeze or act aggressively to protect themselves. These types of behavioural responses, although appropriate and adaptive in some short-term situations, can have a significant negative effect on welfare if they occur excessively or for long periods. 14 Additionally, in the context of air travel, these responses may pose a serious security risk (flight and escape), as well as safety concerns for handlers, who may be unfamiliar or inexperienced with the handling of cats. The behavioural, as well as physiological, signs of stress in cats are listed in the box on page 3.

Assessment of suitability to fly

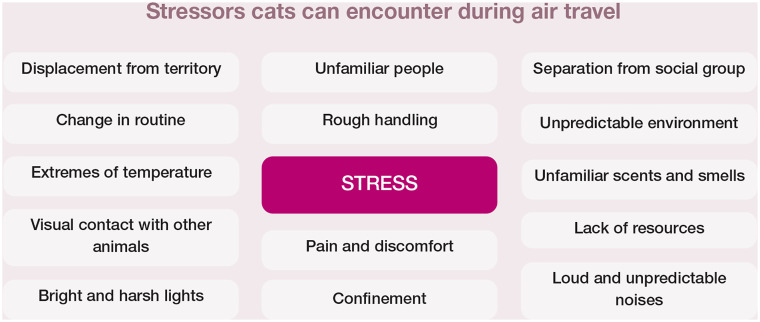

A cat’s fitness to travel should be assessed as soon as air travel is considered. The overall mental, emotional and physical health of the cat needs to be taken into account in order to make a well-considered recommendation regarding the appropriateness of air travel and relocation for that individual, as well as the potential effect on their welfare; this may be particularly relevant for senior or geriatric cats. The decision to travel can pose several ethical challenges and may be largely dependent on any options other than air travel that are available for the cat (eg, rehoming to a local family member), as well as the opinion and emotional attachment of the cat’s owner. The routine ‘fit to fly’ physical examination (Figure 2), which is required by most airlines and authorities issuing travel documents, is usually performed within 10 days of travel, but can also be a useful guidance tool for the initial assessment of a cat’s physical suitability to fly. The cat’s mental and emotional suitability to fly should be assessed and taken into consideration at the same time, or sooner, if possible.

Figure 2.

Example of a ‘fit to fly’ checklist used by the primary author at their practice, German Veterinary Clinic. This can be used as a helpful starting point for veterinarians to create their own checklists based on their individual, country-specific and organisation needs

Managing stress related to air travel

Physical health

When preparing and planning for air travel, physical health is an important consideration. Managing any health conditions and medications, as well as meeting cats’ needs and keeping them comfortable during air travel, for example, by providing absorbent materials in the travel carrier, are all important in ensuring the maintenance of physical health. As changes in health can be a stressor, 22 poor physical health will likely contribute to overall levels of stress.

Chronic health conditions and pre-flight screening

Where a chronic health condition, such as those listed below, is known or suspected, additional planning and input, as well as pre-flight screening, will be required from the veterinary team to increase the cat’s comfort and safety during the flight. This may be particularly relevant to senior or geriatric cats.

Conditions warranting extra consideration may include, but are not limited to:

✜ Osteoarthritis

✜ Diabetes mellitus

✜ Chronic cardiac conditions

✜ Chronic respiratory conditions such as feline asthma

✜ Hypertension

✜ Hyperthyroidism

✜ Chronic renal failure

✜ Any chronic health conditions that lead to dehydration

Depending on the clinical presentation and history of any existing or chronic health conditions, best practice suggests that relevant screening tests, such as blood assays (haematology, biochemistry, renal panels, total thyroxine, N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide), radiography (thoracic, musculoskeletal), continuous ECG tracing (at least 5 mins) for patients with known or suspected cardiac arrythmias, cardiac ultrasonography, blood glucose curves, blood pressure studies and pain assessments, should be performed. In addition, procedures such as intravenous fluid therapy and multimodal analgesia treatment plans may be recommended, and any current treatment should be reviewed and optimised.

Organisation of continued long-term medication

The continuation of any long-term medication needs to be managed throughout the journey, as well as at the destination. This will require pre-planning and effective communication. Any medication should be supplied to the guardian (owner or accompanying person) with an accompanying letter, or it can be pre-ordered to, or dispensed by a local veterinarian at, the destination. If medication is to be given during the journey, detailed instructions should be included in the travel documents.

Food and water intake

Traditional and anecdotal advice from the pet shipping industry is to withhold food for 2-3 h before placing the cat into its carrier to avoid vomiting and/or defecating during the journey. Depending on the route of travel, the cat may receive a meal at a transit location; however, it is possible that the cat will not receive food again until arrival at the destination. Considering a cat’s normal eating pattern of several small meals per day, 23 withholding food for up to 24 h during air travel (including check-in, flight time and the post-arrival period) is likely to be stressful and may also have a significant effect on some medical conditions, such as diabetes mellitus, which will require consideration and management. Unless the cat is known to suffer from travel sickness, the primary author (KJ) does not routinely withdraw food for 2-3 h before the cat is placed in the carrier.

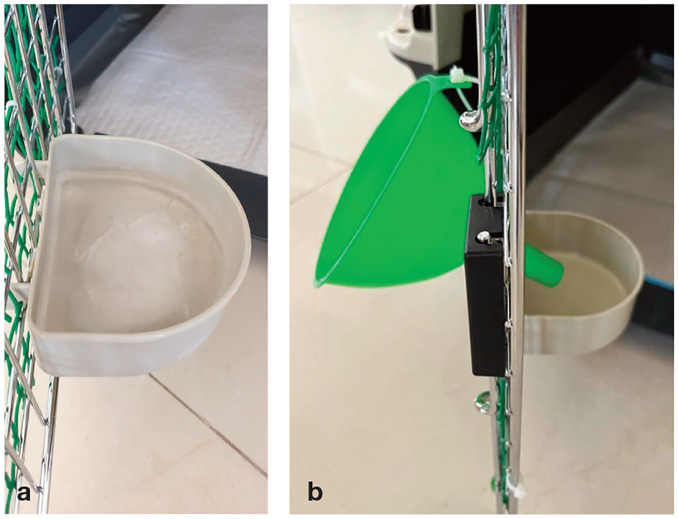

Water can be given in a bowl that is attached to the inside of the carrier throughout the journey. To minimise spillage and provide longer-term access to water, the bowl can be filled and frozen and then attached (Figure 3a) just before placing the cat in the carrier. Depending on the length of the journey, the water bowl may be filled more or less deeply (the average size of carrier water bowls is 4 cm x 11 cm x 10 cm, holding 250 ml of water) and then frozen to allow the ice to melt more or less quickly to provide access to water. On longer journeys, this may result in spillage of water as the ice melts completely; therefore, the primary author tapes a 500 ml bottle of still water to the travel carrier and attaches a funnel to the outside of the cage for journeys over 6 h so the water bowl can be manually refilled by airline or ground handling staff (Figure 3b).

Figure 3.

(a) Before travel, a bowl can be filled with water and frozen in order to minimise spillage and provide longer-term access. (b) A funnel can also be attached to the outside of the carrier for journeys over 6 h so the water bowl can be manually refilled by airline or ground handling staff

Urination and defecation

In the primary author’s experience, it is very rare for cats to soil their travel carriers, even on long journeys. An absorbent pad can be used to soak up any urine or spilled water to prevent the cat becoming soiled or wet; taping it to the bottom of the carrier avoids it slipping. Placing a small litter tray in the carrier has not proven successful owing to space constraints, spillage and, in some cases, aversion or avoidance by the cat.

Logistical considerations

The logistical aspects of managing pet air travel are complex, detailed and ever-changing. While this review cannot provide an extensive discussion of the logistical factors of pet air travel, there is no doubt that careful planning and meticulous preparation have a beneficial impact on the stress and welfare of the animals travelling (see box).

Pet shipping has, in recent years, become an industry of its own and while there are no qualifications necessary to become a pet shipper and no official industry standards other than the IATA LAR 24 (a specific set of guidelines that are updated each year to address any changes and improvements that need to be factored into the daily workings of shipping pets by air 25 ), there are organisations, such as the International Pet and Animal Transportation Association (IPATA) 26 and Animal Transportation Association (ATA), 27 that hold their members to high standards and are a good point of reference to give to pet owners.

The authors highly recommend that veterinarians and pet owners work in collaboration with experienced, reputable pet shipping agents to achieve the best outcome for pets travelling by air.

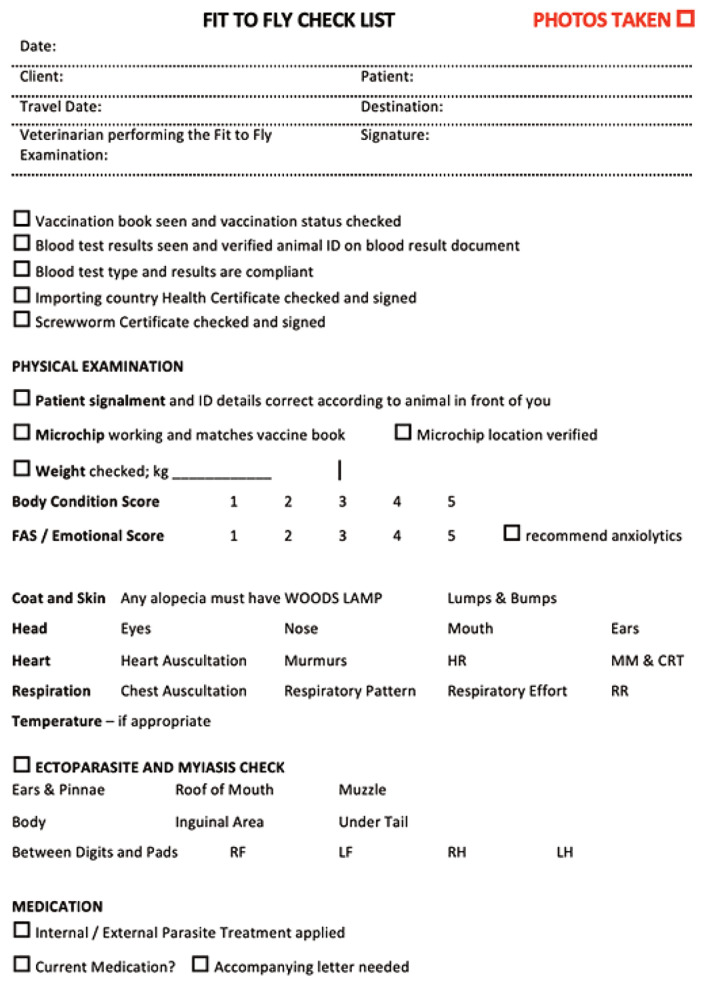

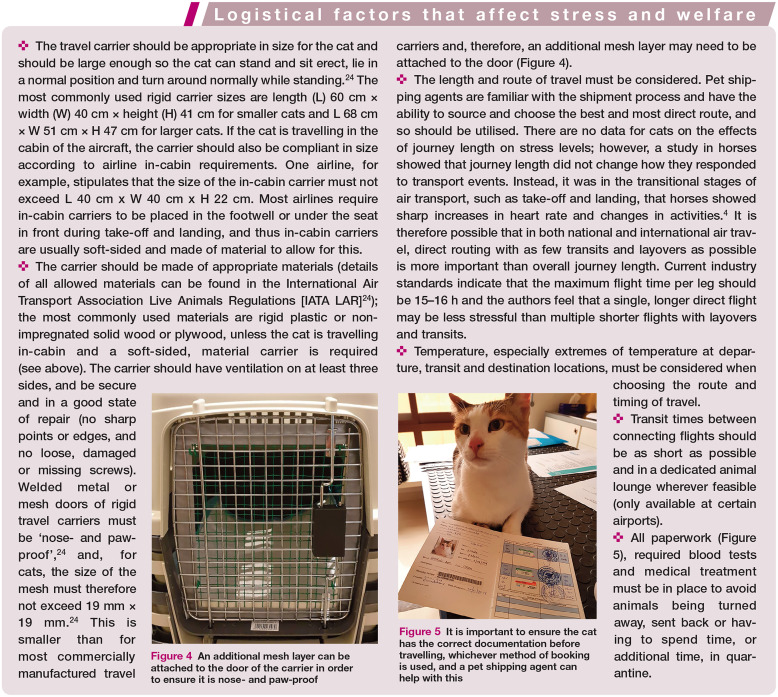

Figure 4.

An additional mesh layer can be attached to the door of the carrier in order to ensure it is nose- and paw-proof

Figure 5.

It is important to ensure the cat has the correct documentation before travelling, whichever method of booking is used, and a pet shipping agent can help with this

Different types of ‘booking’ for air travel

There are a few different ways in which pets can be booked onto flights, each with different advantages and disadvantages (see box). What will be possible and appropriate in each individual case is largely dependent on the airline used, as well as regulations at the countries of departure and arrival. For example, some countries stipulate that all pets arriving by air must arrive as airfreight cargo and not all airlines allow in-cabin air travel or may only allow this up to a certain weight and carrier size; in addition, some airlines may stipulate a maximum number of in-cabin pets per flight.

The type of booking will have implications for stress owing to differences in waiting times, sensory experiences, handling and separation from the owner. It is important to consider each case individually; for example, while some cats may prefer being close to their owners at all times, other cats may struggle with the type of sensory experiences present in a passenger terminal or during an in-cabin flight.

Recently, a Centre of Excellence for Independent Validators (CEIV) for Live Animals Logistics airline accreditation was introduced to establish baseline standards to improve the level of competency, infrastructure and quality management in the handling and transportation of live animals. 29 Increasing numbers of airlines are achieving this accreditation and it is the authors’ recommendation to choose a CEIV-accredited airline for pet transportation where possible.

Stress management methods: a multimodal approach

It must be remembered that both shipping agents and veterinary teams can only influence the process of air travel to a certain point; their influence ceases once the pet has been handed over to the ground handling staff at the airport. Meticulous preparation pre-flight, as well as at the destination, is therefore vital. The importance of airlines and air service providers to educate their teams involved in the pet shipping process worldwide to ensure a safe and successful outcome cannot be emphasised enough. A multimodal approach to stress management should be taken, and the different aspects involved are described below. In order to be successful, stress management methods for air travel should: (1) be effective; (2) be airline compliant (in accordance with individual airline regulations); (3) be easy to accomplish; (4) not negatively affect the animal’s physiology; and (5) be based on evidence.

Crate familiarisation

One of the most reproducible methods for reducing a pet’s stress levels during air transport is for the pet to be acclimatised to the carrier and trained to use it at home (Figure 6). 30 In the home environment, the carrier can become a ‘safe’ zone and/or a place that the pet associates with pleasant experiences, such as feeding, so that on the day of travel, the cat is less likely to be concerned about being inside the carrier. Carrier training via positive reinforcement methods has been shown to reduce behavioural signs of stress in cats during car rides. 9

Figure 6.

Acclimatising the cat to the carrier before air travel at home helps to reduce stress levels during transportation

A number of videos describing cat carrier training can be found at: catfriendlyclinic.org/cat-owners/getting-your-cat-to-the-vet.

Environment and handling

✜ Management of environmental stimuli and handling prior to the flight Minimising sensory input throughout the air travel process aids with reducing stress; examples of how this can be achieved include:

- Placing a towel or blanket over the carrier whenever appropriate to limit visual stimuli but without limiting ventilation. 31

- Protecting the cat’s line of vision from animals and people. 31

- Providing a quiet environment wherever possible and speaking softly.

- Minimising noises that may startle the cat such as phones, alarms, whistles, announcement speakers and fans.

- Playing calming music around the carrier. 31

- Using acoustic dampeners.

- Managing odours by keeping a clean environment wherever this is applicable (veterinary clinic, boarding facility, car/van) and avoiding harsh detergent smells.

- Using feline friendly handling techniques when interacting with the cat. If necessary, using anxiolytic medication (see later) or sedative protocols for certain procedures, such as blood sampling, if necessary and if not immediately prior to the flight.

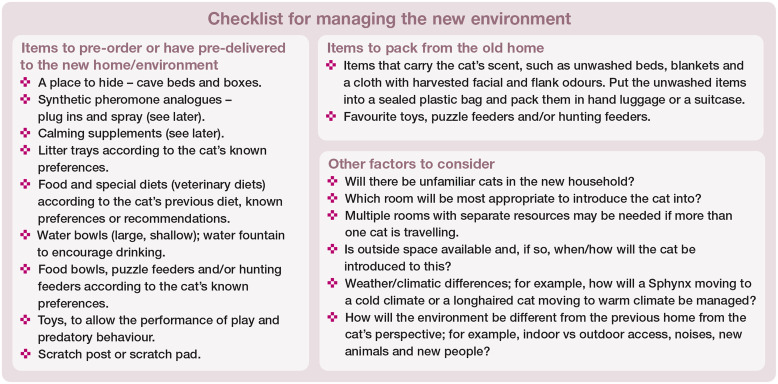

✜ Management of the environment upon arrival The attachment to environmental familiarity makes cats very vulnerable to stress when they are relocated or moved to a new house. 8 Appropriate introduction to a new core territory, following the steps below, reduces stress and the likelihood of problem behaviours due to fear, and a list of things to pack, pre-order and consider in order to best facilitate the transition can be found in ‘Checklist for managing the new environment’ box on page 8.

- Prior to transport, when the cat is still in its original environment, rub a cloth over the cat to harvest some of its flank and facial odours - it is important to only do this when the cat is calm and relaxed - and place the cloth into a sealed bag. 32 Use the cloth to transfer the flank and facial odours to furniture in a quiet room of the new home that the cat will initially be introduced to.

- Place a plug-in of the synthetic pheromone analogue of the F3 fraction of the feline facial pheromone in the quiet room (see later).

- Prepare the quiet room in the new home with food, water, a litter tray and familiar items from the cat’s previous home. Also, provide a place to hide - this can be either a high or low hiding place depending on the cat’s preferences. Hiding is one of the most important coping behaviours expressed by cats confronted with an aversive situation. 33 In one study, cats took between 1 and 5 weeks to adapt to a new environment (boarding kennel vs quarantine); however, each cat needs to be considered as individual and the timeframe may be longer. Allow the cat to explore the room - it should be able to get back into its carrier if desired. Do not pull or coax the cat out of the carrier but rather allow it to come out on its own.

- Allow access to the rest of the house once the cat is completely relaxed in this room. This may take hours to days. 32 Then allow access to additional rooms in the house until the cat has explored the whole house. The cat should be allowed to do this in peace.

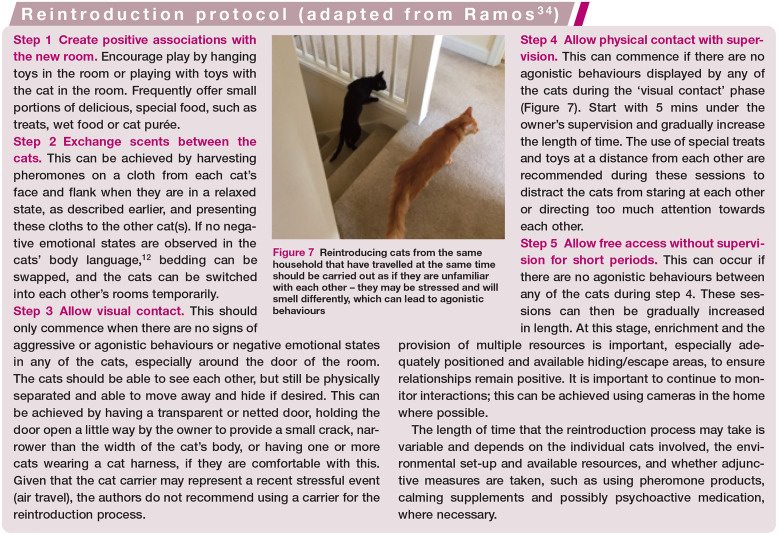

- Reintroduce cats from the same household. If two or more cats from the same household have been transported at the same time, keep them in separate rooms that each contain all the important resources such as litter trays, water and food, resting places, toys and scratching posts 34 and reintroduce the cats as if they are unfamiliar with each other (see box below) - they will smell differently and will have had stressful experiences, both of which may predispose to agonistic behaviours.

Figure 7.

Reintroducing cats from the same household that have travelled at the same time should be carried out as if they are unfamiliar with each other – they may be stressed and will smell differently, which can lead to agonistic behaviours

Synthetic pheromone analogue products: F3 fraction of the feline facial pheromone

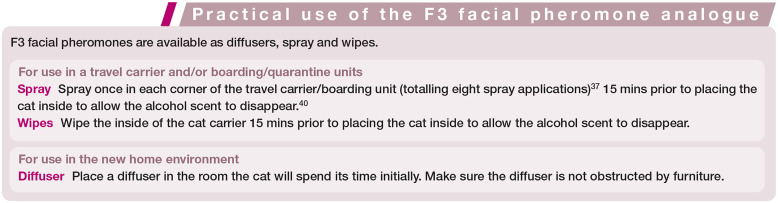

Scent marking through facial rubbing of objects and preferred pathways allows cats to deposit the F3 fraction of the feline facial pheromones in these areas, thus classifying the environment into ‘known objects’ and ‘unknown objects’. 35

A synthetic analogue of the F3 fraction of the feline facial pheromone (Feliway Classic; Ceva Sante Animale) has been reported to reduce anxiety in cats placed in unfamiliar surroundings. 36 It has also shown high efficacy in reducing somatic stress responses and anxiety-related behaviours in cats during car travel. 37

In a new home, personalised scent signals will be absent and there also may be odours from previous resident cats, causing stress and anxiety. 32 One study showed that, compared with a control group, treatment with the F3 synthetic pheromone decreased the amount of time it took for cats to be seen eating after arrival in a holiday home. Furthermore, the cats treated with the F3 synthetic pheromone returned to the holiday home every night, which was not the case in the cats receiving a placebo; additionally, the cats in the treatment group did not urine spray. 38

While the discussion here is limited to the F3 fraction of the feline facial pheromone, as this is most relevant to air travel, other pheromone products, such as appeasing pheromones and pheromone blends, may also be useful, especially if reintroducing cats to each other in a new home.

For guidance on how to use pheromone therapy and the different products, see the paper by Vitale 39 and the box above.

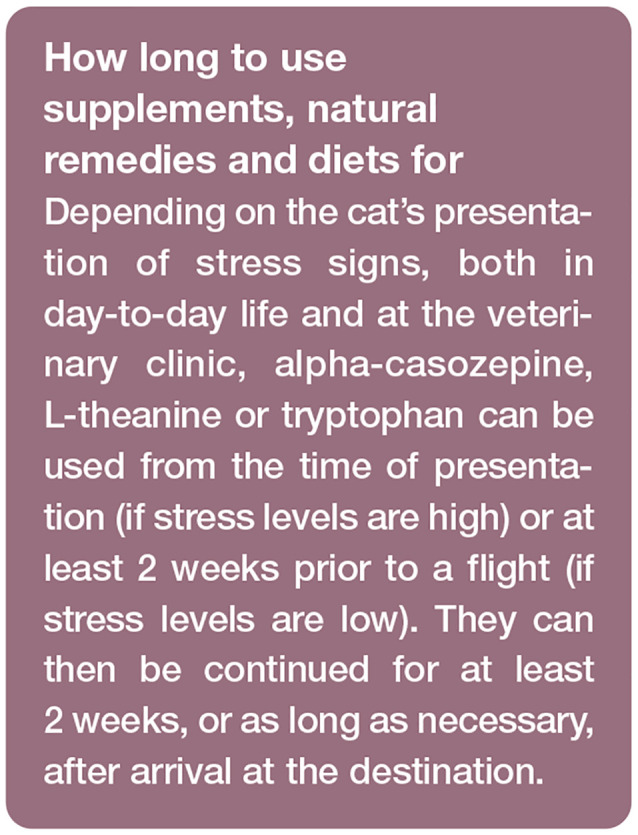

Supplements, natural remedies and diets

✜ Alpha-casozepine Alpha-casozpeine (tryptic bovine alpha-S1-casein hydrolysate) is a milk protein that has a molecular structure similar to gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and has some affinity for GABA A receptors. It is reported to have an anxiolytic effect similar to benzodiazepines but without the same accompanying side effects, such as inco-ordination and disinhibition of aggression. 41 There is evidence that alpha-casozepine is effective in the management of cats that exhibit anxiety in socially stressful conditions 42 and it may influence the autonomic nervous system, inhibiting sweaty paws during stressful situations for cats. 43

Alpha-casozepine is the active ingredient in the veterinary product Zylkene (Vetoquinol). Zylkene can be given once a day, is lactose free, easy to dose, palatable and has not been associated with significant side effects. 42 The authors begin with the recommended manufacturer dose of 15 mg/kg for Zylkene but may increase this up to 45 mg/kg in cats that show more extreme signs of stress, owing to the observed increased effect at higher doses. 43 Alpha-casozepine is also contained in the Royal Canin Feline Calm Diet, which is suggested to reduce the anxiety response of cats when placed in an unfamiliar location. 41

✜ L-Theanine L-Theanine is an amino acid extracted from green tea that competitively binds to glutamate receptors, decreasing excitation and causing an increase in the GABA inhibitory neurotransmitter. It has been shown to reduce anxiety in cats. 44

L-Theanine is the active ingredient in the veterinary product Anxitane (Virbac), which is highly palatable for cats, and is also contained in proprietary blends of the veterinary products Composure (Vetriscience), Composure PRO (Vetriscience) and Solliquin (Nutramax Laboratories). L-Theanine should be dosed according to the manufacturer’s guidelines.

✜ Tryptophan Tryptophan is an essential amino acid and metabolic precursor to melatonin and serotonin (5HT) that has been implicated in the regulation of many behavioural processes such as mood, aggression and susceptibility to stress. Supplementation with tryptophan alone may not be effective because of limitations in its ability to pass the blood-brain barrier as it competes with other large neutral amino acids for a common transporter. 41 There is no veterinary supplement that contains tryptophan alone; however, it is included alongside alpha-casozepine in the Royal Canine Feline Calm Diet, which has been shown to have an anxiolytic effect on cats that are placed in an unfamiliar location. 41 The manufacturer’s guidelines should be followed for the dose.

✜ Magnolia officinalis and Phellodendron amurense Magnolia officinalis and Phellodendron amurense extracts have been shown to have anti-anxiety effects in dogs 45 and are currently available in the proprietary blend of the veterinary product Solliquin (Nutramax Laboratories).

✜ Bach Flower Remedy and cannabidiol Bach Flower Remedy and cannabidiol (CBD) products are frequently mentioned or suggested by pet owners in relation to air travel. It is important to note and relay to owners that there have so far been no studies in animals on any Bach Flower Remedy products but a double-blind, placebo-controlled study in humans showed no clinical efficacy, 46 making it likely that Bach Flower Remedy products show a strong placebo effect. CBD products are currently the cause of much interest and controversy. Based on available information at the time of writing this review, the use of CBD products to relieve signs of stress and anxiety in cats is not recommended by the authors. 47

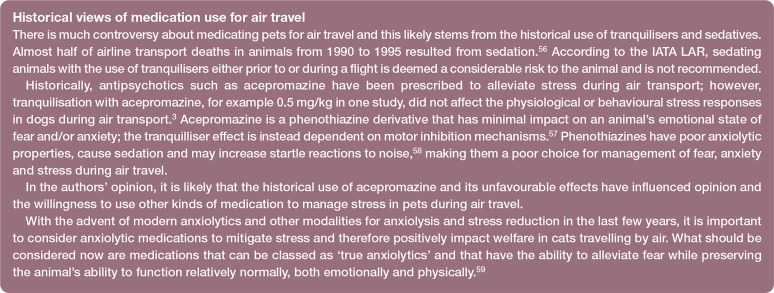

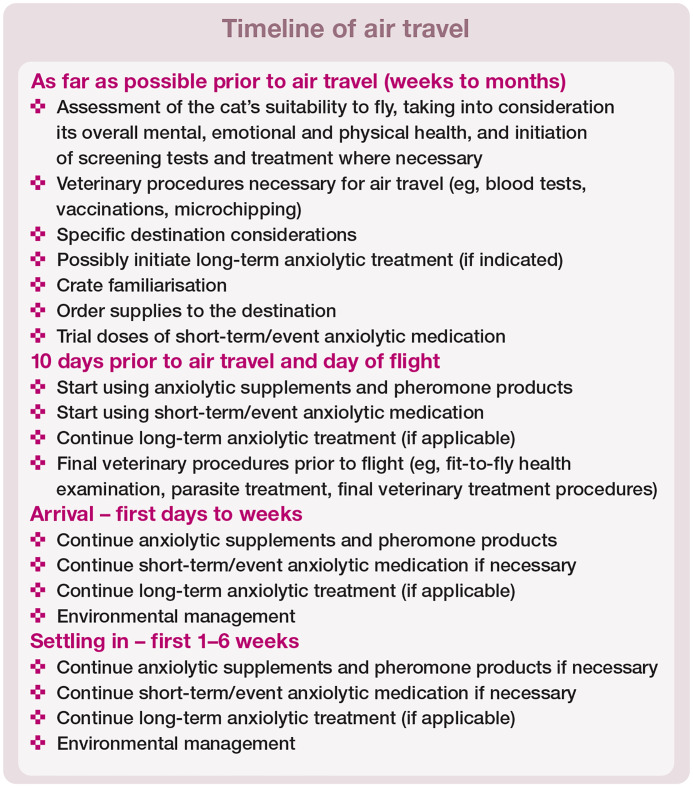

Anxiolytic medication

✜ Off-label use and consent It is important to note that, at the time of publication, only one of the below-mentioned short-term medications is available as a veterinary formulation and licensed for cats - pregabalin (Bonqat; Orion Animal Health), which is approved in the EU, UK, Norway and Iceland for the indication of ‘Alleviation of acute anxiety and fear associated with transportation and veterinary visits’. 48 None of the other below-mentioned short-term medications are available in a veterinary formulation or licensed for use in fear, anxiety or stress in cats; these medications are therefore considered ‘off-label’ and the authors thus recommend obtaining informed consent forms and educating clients on the current ‘off-label’ use of these medications in cats. It should also be noted that there are currently no data available for any of these medications at altitude.

✜ Trial doses and determining the optimal dose for air travel Trial doses of any medication to be given pre-flight are essential to assess the effects in the individual and to screen for unwanted side effects. It is also important to determine the optimal dose for air travel and a balance needs to be established between achieving anxiolysis but not causing levels of sedation or ataxia that might influence the animal’s balance or righting reflex. Cats should be quietly comfortable but alert and able to balance and respond to movements of the carrier. If airlines perceive excessive ataxia or sedation at check-in, they may refuse to accept the cat onto the flight.

When trialling a dose, a low therapeutic dose should be used initially and then titrated upwards until the desired effect has been achieved. Dose ranges for a number of anxiolytic medications can be found in Table 1. Owners should be asked to send videos of the cat 90-120 mins after receiving the trial dose so its effect can be assessed, and provide feedback on whether any unwanted side effects, such as ataxia or signs of sedation, are present. As mentioned in the box, the definition of a ‘true anxiolytic’ is that it has the ability to alleviate fear while preserving the animal’s ability to function relatively normally, both emotionally and physically. 59

Table 1.

Medication chart (continued on page 12)

| Dose range | Onset of action | Duration of action | Side effects | Contraindications | Author comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GABAPENTIN

The authors have had success with the following pre-flight gabapentin protocol: giving the established dose q12h for 2-4 days before the flight and then the final pre-flight dose 90-120 mins prior to placing the cat in the travel carrier | |||||

| 5-25 mg/cat PO q8-12h for more frequent or regular use, with an ‘as needed’ dose range of 50-100 mg/cat PO q8-12h | 90-120 mins;

individual differences should be established during trial doses |

6-12 h; individual differences should be established during trial doses | Hypersalivation and vomiting, and, at higher doses, ataxia and sedation 49 | Patients with renal disease 50 | Anecdotally, veterinary practitioners likely use doses higher than those listed here for veterinary visits, but these are not necessarily suitable for air travel as more profound sedation and ataxia are not desired |

| PREGABALIN

The authors have not yet had the opportunity to use Bonqat (Orion Animal Health) as it is not yet available in their countries of practice, but this may be a good option for the future | |||||

| 5-10 mg/cat PO

q12h |

90-120 mins;

individual differences should be established during trial doses |

6-12 h; individual differences should be established during trial doses | Hypersalivation and vomiting, and, at higher doses, ataxia and sedation 49 | Patients with renal disease 50 | |

| TRAZODONE

The authors currently do not use trazodone very often due to its increased sedative effects | |||||

| 15-25

mg/cat PO q12-24h, or up to 50 mg/cat for ‘as needed’ usage 51 |

90-120 mins;

individual differences should be established during trial doses |

6-12 h; individual differences should be established during trial doses | Lethargy, sedation, vomiting, increased vocalisation, restlessness, agitation 52 | Cautious use in patients with cardiac disease; may lead to hypotension 53 | The pre-flight dose should be given 90-120 mins prior to placing the cat in the travel carrier |

| BENZODIAZEPINES

Benzodiazepines are not frequently utilised for air travel by the authors due to the risk of side effects, including ataxia and increased appetite during a period when food is being withheld, and as there are alternative medication choices available that pose less risk of side effects | |||||

| Alprazolam | |||||

| 0.125-0.25 mg/cat PO

q8-12h |

30-45 mins;

individual differences should be established during trial doses |

Short/medium: 2-6 h; individual differences should be established during trial doses | Sedation, ataxia, muscle relaxation, increased appetite (this may not be beneficial when food is being withheld for long periods due to travel), paradoxical excitation, disinhibition of behaviour, which may lead to aggression | Patients with hepatic or renal disease; doses should be decreased in older or obese patients with known sensitivity to benzodiazepines; pregnant or lactating females; cats with glaucoma; should not be used in conjunction with itraconazole or ketoconazole | |

| Clonazepam | |||||

| 0.25-1

mg/cat PO q12-24h |

45-60 mins;

individual differences should be established during trial doses |

Long: 8-12 h; individual differences should be established during trial doses | Sedation, ataxia, muscle relaxation, increased appetite (this may not be beneficial when food is being withheld for long periods due to travel), paradoxical excitation, disinhibition of behaviour, which may lead to aggression | Patients with hepatic disease due to extensive metabolism in the liver; patients with renal disease; patients with a known sensitivity to benzodiazepines; pregnant or lactating females; cats with glaucoma | |

| Diazepam | |||||

| 1-2.5

mg/cat PO (but avoid where possible in cats) |

45-60 mins;

individual differences should be established during trial doses |

Medium/long: up to 6 h; individual differences should be established during trial doses | Sedation, ataxia, muscle relaxation, increased appetite (this may not be beneficial when food is being withheld for long periods due to travel), paradoxical excitation, disinhibition of behaviour, which may lead to aggression | Oral diazepam has been associated with idiopathic hepatic necrosis in one case series 54 (single case series that has not been replicated) and is therefore not frequently used | |

| Lorzepam | |||||

| 0.125-0.25 mg/cat PO

q12-24h |

30-45 mins;

individual differences should be established during trial doses |

Short: 2-4 h;

individual differences should be established during trial doses |

Sedation, ataxia, muscle relaxation, increased appetite (this may not be beneficial when food is being withheld for long periods due to travel), paradoxical excitation, disinhibition of behaviour, which may lead to aggression | Cats with a known sensitivity to benzodiazepines; pregnant or lactating females; cats with glaucoma | |

| Oxazepam | |||||

| 1-2.5

mg/cat PO q12-24h |

45-60 mins; individual differences should be established during trial doses | Medium: 4-6 h; individual differences should be established during trial doses | Sedation, ataxia, muscle relaxation, increased appetite (this may not be beneficial when food is being withheld for long periods due to travel), paradoxical excitation, disinhibition of behaviour, which may lead to aggression | Cats with a known sensitivity to benzodiazepines; pregnant or lactating females | In animals with hepatic or renal disease, a benzodiazepine without active metabolites, such as oxazepam, is recommended |

| MAROPITANT (not an anxiolytic) | |||||

| 1 mg/kg SC or PO | 45-60 mins | 24 h | Diarrhoea, anorexia lethargy, sedation, pain at injection site 55 | Gastrointestinal obstruction, ingestion of toxins | Oral tablets may be cost-prohibitive in some countries |

✜ Gabapentin and pregabalin The anxiolytic effect of gabapentin and pregabalin is believed to be mediated by the binding of voltage-sensitive calcium channels in the amygdala, preventing the release of the excitatory neurotransmitter glutamate and the associated fear response. 49 Peak levels occur about 100 mins after dosing in cats and gabapentin at a dosage of 50-100 mg/cat PO reduces visible signs of stress 1-2 h after administration. 49 Gabapentin at a dosage of 100 mg/cat PO helps to facilitate transport and compliance during veterinary examinations. 49 In one study a single pre-appointment dose of gabapentin was shown to cause a significant reduction in stress-related behaviours in the transportation and examination of cats, 55 and in another study cats showed reduced fear-based aggressive behaviours during a veterinary examination after oral administration of gabapentin 2 h prior. 60

Bonqat (Orion Animal Health) is currently the only pregabalin product licensed for cats and is approved in the EU, UK, Norway and Iceland for the indication ‘Alleviation of acute anxiety and fear associated with transportation and veterinary visits’, which means that the product is, as per label, approved for single use. 48 As gabapentin and pregabalin have no active intermediate metabolites and minimal passage through the cytochrome (CYP) 450 metabolism, the likelihood of side effects is low. 61 If side effects occur, they typically include hypersalivation and vomiting or, if given at a higher dosage, ataxia and sedation. 55 Pregabalin is considered to have fewer side effects than gabapentin and to be more potent. 61

As renal excretion is the main route of elimination, care should be taken when prescribing gabapentin to patients with renal disease 61 and a lower dose should be used 50 or an alternative medication considered.

See Table 1 for further information about gabapentin and pregabalin.

✜ Trazodone Trazodone is a serotonin antagonist and reuptake inhibitor (SARI) and has been used successfully for its anxiolytic and mild sedative effects. It has been shown to be useful for cats in the amelioration of signs of anxiety associated with car transportation or veterinary visits. 52 Further information can be found in Table 1.

✜ Benzodiazepines Benzodiazepines are anxiolytic medications 62 that facilitate GABA activity by binding to GABA-A receptors in the central nervous system 51 and are potentially useful for any problems involving fear, anxiety or phobias. 59 These medications have a rapid onset of action, and the effects last between 2 and 12 h, depending on the medi-cation. 62 For further information about the benzodiazepines alprazolam, clonazepam, diazepam, lorazepam and oxazepam see Table 1.

✜ Another useful medication: maropitant Indicated for the treatment of motion sickness and other causes of nausea in dogs and cats, 63 maropitant (not an anxiolytic) acts centrally and peripherally by blocking substance P, the neurotransmitter associated with vomiting. 64 See Table 1 for further information.

✜ Use and continuation of long-term anxio-lytic medication There are a few situations in which a cat may be treated with a long-term anxiolytic medication:

- The cat has previously been diagnosed with a mental or emotional ill health disease and prescribed a long-term anxiolytic medication such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants, azapirone or mono-amine oxidase inhibitors.

- The cat has, in the course of evaluation and preparation for air travel, been diagnosed with a mental or emotional ill health disease and been prescribed a long-term anxiolytic medication as mentioned above.

Long-term anxiolytic medications require at least 4-6 weeks to reach therapeutic levels and this timeframe should be considered if an anxiolytic effect is desired for air travel. The short-term medications mentioned earlier (gabapentin and pregabalin, trazodone and benzodiazepines) as part of the stress management methods of air travel are intended specifically for the management of the flight and events surrounding the flight and can be given in addition to long-term anxiolytic medications as part of a polypharmacy protocol. Unwanted drug interactions between psychopharmaceutical medications and other long-term medications are rare; however, the authors recommend checking for contraindications and interactions of any medications prescribed.

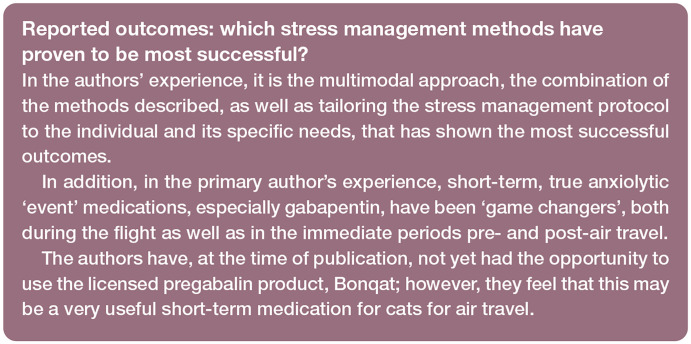

Timeline

When considering stress posed by air travel, it is important to not only consider the immediate periods of check-in and the flight, but to bear in mind that stressors can be present for considerably longer, both pre- and post-flight.

Important periods during the process of air travel

(1) Packers and unfamiliar people in home, disruption of pheromone marks, disruption of routine leaving the familiar territory.

(2) Veterinary visits to prepare for travel. This may include vaccinations, blood tests, internal and external parasite treatment and the ‘fit to fly’ pre-travel health examination.

(3) Potential boarding in a cattery.

(4) Car travel.

(5) Arrival at the airport and loading.

(6) The flight and the effects of altitude during the flight.

(7) Offloading and handling at the destination.

(8) Car ride from the airport to the final destination.

(9) Possible quarantining and/or boarding in a cattery.

(10) Arrival in a new environment, new territory.

The box below shows the proposed timeline when planning the preparation of cats for air travel.

Key Points

✜ Air travel is likely stressful for cats but there are strategies that can be used to reduce and manage the stress experienced.

✜ Using a multimodal stress management approach is important in order to reduce the amount of stress experienced as much as possible.

✜ Physical, mental and emotional health should be evaluated, and health screening tests should be performed, and treatment initiated or optimised, prior to air travel.

✜ It may be helpful to use modern anxiolytic medications, supplements, diets and pheromone analogues.

✜ The recommendations in this review can be adapted to other means of transport, such as long car journeys and travel by ferry, as well as time spent in a holiday home.

✜ It is important for veterinarians and pet owners to collaborate with experienced and reputable pet shipping agents to assist with the logistical process, as this has implications for stress and welfare. While veterinarians are concerned with the animal’s physical, mental and emotional health and welfare, they should not be expected to have in-depth knowledge about the logistical complexities and details of pet air travel.

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval: This work did not involve the use of animals and therefore ethical approval was not specifically required for publication in JFMS.

Informed consent: This work did not involve the use of animals (including cadavers) and therefore informed consent was not required. No animals or people are identifiable within this publication, and therefore additional informed consent for publication was not required.

Contributor Information

Katrin Jahn, DrMedVet, CertVA, MANZCVS (Veterinary Behaviour), MRCVS* German Veterinary Clinic, Villa 112, 39th Street, Khalifa City A, Abu Dhabi, UAE.

Theresa DePorter, BSc, DVM, MRCVS, DECAWBM, DACVB, MRCVS Oakland Veterinary Referral Services, 1400 S Telegraph Road, Bloomfield Hills, MI 48302, USA.

References

- 1. US Department of Transportation. Pets. www.transportation.gov/tags/pets (2020, accessed 27 December 2021).

- 2. Condor Ferries. Pet travel statistics 2020-2021. www.condorferries.co.uk/pet-travel-statistics (2020, accessed 27 December 2021).

- 3. Bergeron R, Scott SL, Emond JP, et al. Physiology and behavior of dogs during air transport. Can J Vet Res 2002; 66: 211-216. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Stewart M, Foster TM, Waas JR. The effects of air transport on the behaviour and heart rate of horses. Appl Anim Behav Sci 2003; 80: 143-160. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Snyder RJ, Perdue BM, Powell DM, et al. Behavioral and hormonal consequences of transporting giant pandas from China to the United States. J Appl Anim Welf Sci 2012; 15. DOI: 10.1080/10888705.2012.624046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Amat M, Camps T, Manteca X. Stress in owned cats: behavioural changes and welfare implications. J Feline Med Surg 2016; 18: 577-586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mills D, Braem Dube M, Zulch H. How animals respond to change. In: Mills D, Braem Dube M, Zulch H. (eds). Stress and pheromonatherapy in small animal clinical behaviour. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2013, pp 3-36. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bradshaw J. What is a cat and why can cats become stressed or distressed? In: Ellis S, Sparkes A. (eds). ISFM guide to feline stress and health. Shaftesbury: Blackmore Group, 2016, pp 19-29. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pratsch L, Mohr N, Palme R, et al. Carrier training cats reduces stress on transport to a veterinary practice. App Anim Behav Sci 2018; 206: 64-74. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Taylor S. Causes of stress and distress for cats in the veterinary clinic. In: Ellis S, Sparkes A. (eds). ISFM guide to feline stress and health. Shaftesbury: Blackmore Group, 2016, pp 56-64. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Moberg GP. Biological response to stress: implications for animal welfare. In: Moberg GP, Mench JA. (eds). The biology of animal stress: basic principles and implications for animal welfare. Wallingford: CAB International, 2000, pp 1-22. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Heath S. Understanding feline emotions: … and their role in problem behaviours. J Feline Med Surg 2018; 20: 437-444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Taylor S, Sparkes AH, Briscoe K, et al. ISFM consensus guidelines on the diagnosis and management of hypertension in cats. J Feline Med Surg 2017; 19: 288-303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gruen ME, Thomson A, Clary B, et al. Conditioning laboratory cats to handling and transport. Lab Anim (NY) 2013; 42: 385-389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sparkes A, German A. Impact of stress and distress on physiology and clinical disease. In: Ellis S, Sparkes A. (eds). ISFM guide to feline stress and health. Shaftesbury: Blackmore Group, 2016, pp 42-53. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Carney H, Gourkow N. Impact of stress and distress on cat behaviour and body language. In: Ellis S, Sparkes A. (eds). ISFM guide to feline stress and health. Shaftesbury: Blackmore Group, 2016, pp 32-39. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Stella JL, Lord LK, Buffington CA. Sickness behaviors in response to unusual external events in healthy cats and in cats with feline interstitial cystitis. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2011; 238: 67-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Heath S. Feline aggression. In Horwitz DF, Mills DS. (eds). BSAVA manual of canine and feline behavioural medicine. Gloucester: British Small Animal Veterinary Association, 2006, p 216. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Carlstead K, Brown JL, Strawn W. Behavioral and physiological correlates of stress in laboratory cats. Appl Anim Behav Sci 1993; 38: 143-158. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mills D, Braem Dube M, Zulch H. Feline house soiling problems. In: Mills D, Braem Dube M, Zulch H. (eds). Stress and pheromona-therapy in small animal clinical behaviour. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2013, pp 149-169. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Neilson JC. House soiling by cats. In: Horwitz DF, Mills DS. (eds). BSAVA manual of canine and feline behavioural medicine. Gloucester: British Small Animal Veterinary Association, 2002, pp 117-126. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Horwitz DF, Rodan I. Behavioral awareness in the feline consultation: understanding physical and emotional health. J Feline Med Surg 2018; 20: 423-436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sadek T, Hamper B, Horwitz D, et al. Feline feeding programs: addressing behavioral needs to improve feline health and wellbeing. J Feline Med Surg 2018; 20: 1049-1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. International Air Transport Association. LAR (live animal regulations). https://www.iata.org/en/publications/store/live-animals-regulations (2021, accessed 29 December 2021).

- 25. Ghandour I. Transporting small animals by air: welfare aspects. Companion Anim 2017; 22:284-288. [Google Scholar]

- 26. International Pet and Animal Transportation Association. www.ipata.org (2021, accessed 29 December 2021).

- 27. Animal Transportation Association. www.animaltransportationassociation.org (2021, accessed 29 December 2021).

- 28. International Cat Care. Cat friendly resources to support travel. https://icatcare.org/app/uploads/2022/06/icc-travel-v5-scaled.jpg (2022, accessed 18 November 2022).

- 29. International Air Transport Association. CEIV live animals. www.iata.org/en/programs/cargo/live-animals/ceiv-animals/ (2021, accessed 10 January 2022).

- 30. Tateo A, Zappaterra M, Covella A, et al. Factors influencing stress and fear-related behaviour of cats during veterinary examinations. Ital J Anim Sci 2021; 20: 46-58. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rodan I, Sundahl E, Carney H, et al. AAFP and ISFM feline-friendly handling guidelines. J Feline Med Surg 2011; 13: 364-375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bowen J, Heath S. Feline fear, anxiety and phobia problems. In: Bowen J, Heath S. (eds). Behaviour problems in small animals. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier, 2005, pp 163-176. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rochlitz I, Podberscek AL, Broom DM. Welfare of cats in a quarantine cattery. Vet Rec 1998; 143: 35-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ramos D. Common feline problem behaviors - aggression in multi-cat households. J Feline Med Surg 2019; 21: 221-233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pageat P, Gaultier E. Current research in canine and feline pheromones. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2003; 33: 187-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Griffith CA, Steigerwald ES, Buffington CAT. Effects of a synthetic facial pheromone on behavior of cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2000; 217: 1154-1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gaultier E, Pageat P, Tessier Y. Effect of a feline facial pheromone analogue (Feliway) on manifestations of stress in cats during transport. Proceedings of the 32nd Congress of the International Society for Applied Ethology; 1998 Jul 21-25; Clermont-Ferrand, France. Clermont-Ferrand: INRA, 1998, p 198. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pageat P, Tessier Y. Usefulness of F3 synthetic pheromone (Feliway) in preventing behaviour problems in cats during holidays. Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Veterinary Behavioural Medicine; 1997 Apr 1-2; Birmingham, England. Wheathampstead: Universities Federation for Animal Welfare, 1997, p 231. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Vitale KR. Tools for managing feline problem behaviors: pheromone therapy. J Feline Med Surg 2018; 20: 1024-1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pereira JS, Fragoso S, Beck A, et al. Improving the feline veterinary consultation: the usefulness of Feliway spray in reducing cats’ stress. J Feline Med Surg 2016; 18: 959-964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Landsberg G, Milgram B, Mougeot I, et al. Therapeutic effects of an alpha-casozepine and L-tryptophan supplemented diet on fear and anxiety in the cat. J Feline Med Surg 2017; 19: 594-602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Beata C, Beaumont-Graff E, Coll V, et al. Effect of alpha-casozepine (Zylkene) on anxiety in cats. J Vet Behav Clin Appl Res 2007; 2: 40-46. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Makawey A, Iben C, Palme R. Cats at the vet: the effect of alpha-Si casozepine. Animals 2020; 10. DOI: 10.3390/ani10112047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Dramard V, Kern L, Hofmans J, et al. Clinical efficacy of L-theanine tablets to reduce anxiety related emotional disorders in cats: a pilot open-label clinical trial [abstract]. J Vet Behav 2007; 85-86. [Google Scholar]

- 45. DePorter TL, Landsberg GM, Araujo JA, et al. Harmonease chewable tablets reduce noise-induced fear and anxiety in a laboratory canine thunderstorm simulation: a blinded and placebo-controlled study. J Vet Behav Clin Appl Res 2012; 7: 225-232. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Armstrong NC, Ernst E. Placebo-controlled trial of a Bach Flower Remedy. Complement Ther Nurs Midwifery 2001; 7: 215-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. American Veterinary Medical Association. Cannabis use and pets. https://www.avma.org/resources-tools/animal-health-and-welfare/cannabis-use-and-pets (2021, accessed 21 January 2022).

- 48. Lamminen T, Korpivaara M, Suokko M, et al. Efficacy of a single dose of pregabalin on signs of anxiety in cats during transportation - a pilot study. Front Vet Sci 2021; 8. DOI: 10.3389/fvets.2021.711816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sinn L. Advances in behavioral psychophar-macology. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2018; 48: 457-471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Quimby JM, Lorbach SK, Saffire A, et al. Serum concentrations of gabapentin in cats with chronic kidney disease. J Feline Med Surg 2022; 22: 1260-1266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Stahl SM. Anxiety disorders and anxiolytics. In: Stahl SM. (ed). Stahl’s essential psychophar-macology - neuroscientific basis and practical applications. 4th ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013, pp 388-419. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Stevens B, Frantz E, Orlando J, et al. Efficacy of a single dose of trazodone hydrochloride given to cats prior to veterinary visits to reduce signs of transport- and examination-related anxiety. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2016; 249: 202-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Fries RC, Kadotani S, Vitt JP, et al. Effects of oral trazodone on echocardiographic and hemodynamic variables in healthy cats. J Feline Med Surg 2019; 21; 1080-1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Center SA, Elston TH, Rowland PH, et al. Fulminant hepatic failure associated with oral administration of diazepam in 11 cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1996; 209: 618-625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Haaften K, Forsythe L, Stelow E, et al. Effects of a single preappointment dose of gabapentin on signs of stress in cats during transportation and veterinary examination. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2017; 251: 1175-1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Tennyson A. Air transport of sedated pets may be fatal. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1995; 207: 684. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Piotti P, Uccheddu S, Alliani M, et al. Management of specific fears and anxiety in the behavioral medicine of companion animals: punctual use of psychoactive medications. Dog Behav 2019; 5: 23-30. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Seibert L, Crowell-Davis S. Antipsychotics. In: Cromwell-Davis SL, Murray TF, de Souza Dantas LM. (eds). Veterinary psychophar-macology. 2nd ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, 2019, pp 201-215. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Crowell-Davis SL, Landsberg GM. Pharmacology and pheromone therapy. In: Horwitz DF, Mills DS. (eds). BSAVA manual of canine and feline behavioural medicine. 2nd ed. Gloucester: British Small Animal Veterinary Association, 2018, pp 245-258. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kruszka M, Graff E, Medam T, et al. Clinical evaluation of the effects of a single oral dose of gabapentin on fear-based aggressive behaviors in cats during veterinary examinations. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2021; 259; 1285-1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Denenberg S. Psychopharmacology. In: Denenberg S. (ed). Small animal veterinary psychiatry. Oxfordshire: CABI, 2021, pp 142-168. [Google Scholar]

- 62. de Souza Dantas ML, Crowell-Davis SL. Benzodiazepines. In: Crowell-Davis SL, Murray TF, de Souza Dantas ML. (eds). Veterinary psychopharmacology. 2nd ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Blackwell, 2019, pp 67-92. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Hickman MA, Cox SR, Mahabir S, et al. Safety, pharmacokinetics and use of the novel NK-1 receptor antagonist maropitant (Cere-niaTM) for the prevention of emesis and motion sickness in cats. J Vet Pharmacol Ther 2008; 31; 220-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. DePorter T, Landsberg GM, Horwitz D. Tools of the trade: psychopharmacology and nutrition. In: Rodan I, Heath S. (eds). Feline behavioral health and welfare. St Louis, MO: Elsevier, 2016, pp 245-267. [Google Scholar]