Abstract

Practical relevance:

Traumatic abdominal wall rupture is a potentially serious injury in cats. Feline and general practitioners should be up to date with the significance of these injuries and the procedures required to correct them.

Clinical challenges:

It is essential that the surgeon understands the local anatomy and adheres to Halsted’s principles in order that postoperative morbidity and mortality are kept to a minimum.

Equipment:

Standard general surgical equipment is required together with the facilities to provide adequate pre-, intra- and postoperative patient care.

Evidence base:

The authors have drawn on evidence from the published literature, as well as their own clinical experience, in developing this review aimed all veterinarians who want to update their skills in managing feline abdominal wall trauma.

Keywords: Abdominal wall trauma, surgical techniques, anatomy, treatment approaches, decision-making

Pathophysiology

Traumatic abdominal wall ruptures are defined as protrusions of abdominal content through a trauma-induced defect in the abdominal body wall. Most commonly blunt trauma such as road traffic accidents, falls, ballistic injuries or bite wounds are involved, and there is usually an associated and sudden increase in intra-abdominal pressure or avulsion forces. The location of the rupture depends on the direction of the biomechanical forces and the magnitude of the intra-abdominal pressure changes. Abdominal wall ruptures in cats are most frequently prepubic, paracostal, inguinal and dorsolateral (muscle avulsion from transverse processes of lumbar vertebrae) in location.3–5

As a result, up to 75% of traumatised small animal patients with abdominal ruptures have other significant injuries. Most of these additional injuries are orthopaedic in nature but damage to intraabdominal organs is often found as well. 6

Local anatomy

The abdominal wall extends from the diaphragm to the pelvic canal. It maintains abdominal integrity and confines the abdominal organs within the largest cavity in the body, providing support and strength.

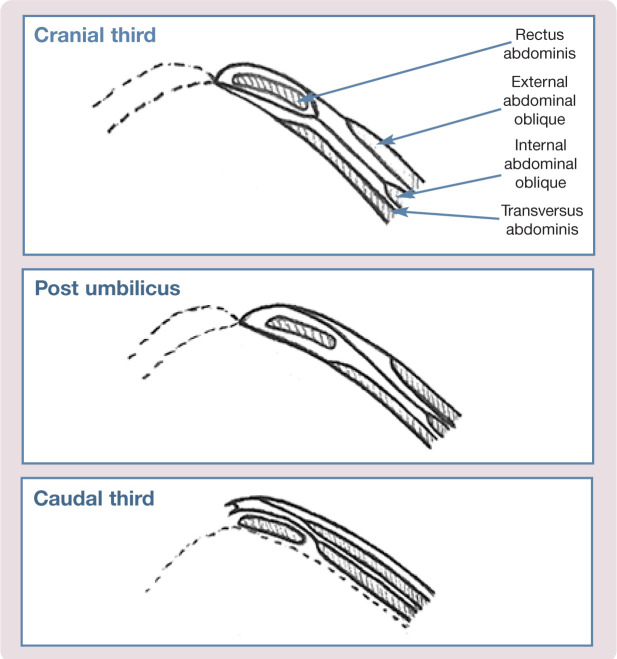

The linea alba is formed by converging fibres from the tendinous aponeuroses of the external abdominal oblique, internal abdominal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles. The external abdominal oblique aponeurosis always runs superficially to the rectus abdominis muscle. The location of the aponeurosis of the internal abdominal oblique varies along the length of the abdomen. In the cranial third of the abdominal wall, fibres pass both deep and superficially to the rectus abdominis muscle. From the umbilicus, all of the internal abdominal oblique fibres run superficially to the rectus abdominis. Fascial fibres of the transversus abdominis pass deep to the rectus abdominis muscle in the cranial two-thirds of the abdominal wall, but in the caudal third, fibres run only superficially to the rectus abdominis muscle (Figure 1).3,7

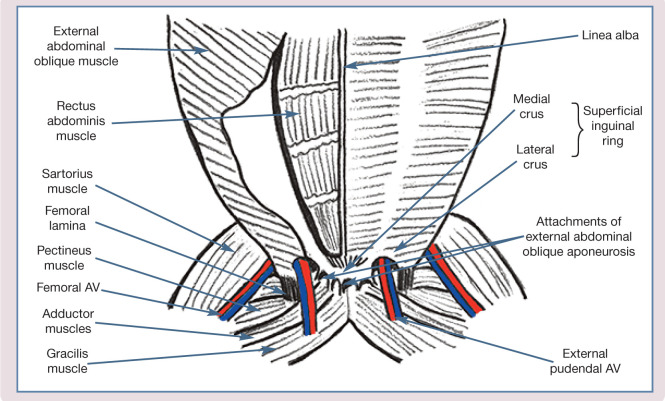

According to studies on the anatomy of the prepubic area in dogs and cats by Constantinescu et al, 8 a true prepubic tendon does not exist in cats. However, the two crura of the superficial inguinal ring are firmly attached to the cranial border of the pubis on both sides of the insertion of the pectineus muscle on the ileopubic eminence. Attachments of the aponeurosis of the external abdominal oblique muscle to the tendon of the pectineus muscle contribute to making the area as strong as the prepubic tendon in dogs (Figure 2). 8

Figure 1.

Abdominal wall muscular anatomy. Modified from Tobias and Johnston 5

Stabilisation

The importance of a thorough clinical examination and diagnostic work-up cannot be over-emphasised in these cases. Initial analgesia is clearly mandatory, and each trauma patient must be triaged and their cardiovascular and pulmonary functions assessed as a priority. Resuscitation (oxygen, fluid therapy, etc) should then be started immediately when required. 9 Open wounds should be bandaged until initial stabilisation and clinical examination are complete.

It is important to determine the aetiology when possible as abdominal wall ruptures are often associated with concurrent injuries and/or complications. For example, in dogs, 50% of body wall ruptures that are contaminated at the time of injury become infected. Concurrent injuries include trauma to other organs, fractures and diaphragmatic or spinal injuries. 4 This is why the patient should always undergo a full general, orthopaedic and neurological examination.

Once the initial stabilisation and a full examination have been performed, laboratory evidence of any organ dysfunction should be obtained (urinalysis, complete blood count and measurement of total protein, albumin and electrolytes). Radiographs and ultrasound examination are likely to be useful to assess concurrent injuries such as fractures, diaphragmatic rupture, free abdominal fluid and pulmonary contusions.

Clinical signs

The most common clinical signs in cases of abdominal wall rupture are a bulging swelling beneath the skin, bruising or asymmetry of the abdominal contour. However, the swelling can appear later on, in some cases 24 h or up to several days (6 days in one report 10 ) after the trauma, as abdominal content slides through the hernia. Clipping the area is often helpful to reveal the extent of the trauma (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Structures of the pubic area in the cat. AV = artery and vein. Modified from Constantinescu et al 8

Concomitant injuries may be responsible for the animal’s clinical signs at presentation and the existence of an abdominal wall rupture and other injuries can be overlooked. In a study including 36 cats and dogs, five cases (4/26 dogs and 1/10 cats) did not have their traumatic body wall rupture diagnosed within 24 h of hospitalisation, leading to three cases having orthopaedic surgery before the body wall defect was detected. 5 This highlights how difficult the identification of a traumatic body wall rupture can be in animals with multiple traumatic injuries.

Diagnostics

Some abdominal wall ruptures can be diagnosed on abdominal palpation alone; however, most cases will require imaging. Radiographs are usually diagnostic when the defect is palpable but, when it is not, traumatic abdominal wall rupture can be missed. In a study involving seven cats with what was described as cranial pubic tendon rupture, radiography did not detect the rupture in the two cases that were not diagnosed on physical examination. 10 Similarly, in a study on traumatic body wall herniation in dogs and cats (predominantly dogs), radiographs were diagnostic or suggestive of a traumatic body wall hernia in 20 cases out of 31. 5

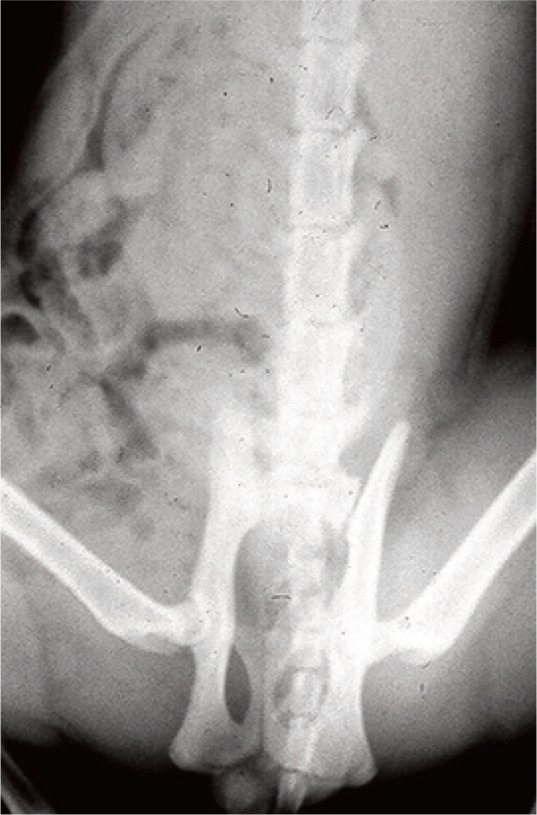

Signs of abdominal wall rupture on radiographs include a discontinuous abdominal wall (loss of abdominal strip), absence of an abdominal organ from its normal location, subcutaneous emphysema and free abdominal gas (Figure 4). 3

Figure 3.

Cat with an abdominal wall rupture in the prepubic area

For cases where the rupture cannot be identified on radiography, ultrasound examination or even CT may be necessary. Findings suggestive of abdominal wall rupture on ultrasound are free abdominal gas or fluid, lack of continuity of the body wall and/or displaced organs. 11

Unlike hernias, acute traumatic ruptures lack a serosa-lined hernial sac, which makes their content more prone to adhesion to extra-abdominal structures and incarceration. Both swelling resulting from acute inflammation and wound contraction during healing may in addition cause strangulation of organs. It is essential to assess for the existence of adhesion, incarceration or strangulation in order to choose the appropriate treatment. 3 If any of these complications are suspected based on physical examination, ultrasound examination or further advanced imaging modalities are likely to be required. 12

Treatment approaches

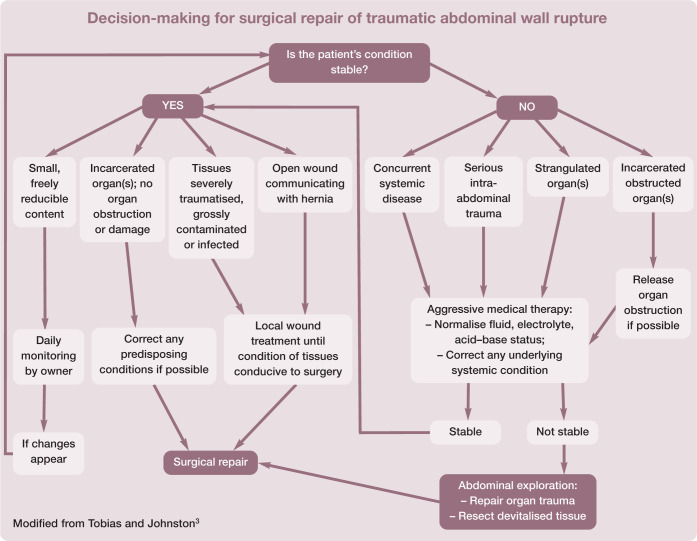

Surgery is not always required, as some small defects with reducible content can be managed conservatively. The appropriate timing for intervention in stable animals is controversial. In some cases where there is a large defect, delaying the surgery for several days may be necessary to allow for improvement in the blood supply, reduction of oedema and resolution of haemorrhage. However, prolonged delay may lead to further potential complications, such as incarceration or strangulation of organs as the wound contracts. Penetrating abdominal wounds or serious intra-abdominal injuries (ie, presence of significant amount of free fluid, evidence of incarceration/strangulation, etc) are indications for immediate emergency surgery once the patient is stabilised. Each case is different and has to be assessed as an individual, with the timing for intervention based on the severity of the initial trauma and the ability to stabilise the patient.

A wide exposure should be planned as it is often difficult to know the exact extent of the defect prior to surgery and extension of the incision is frequently needed. Multiple surgical approaches have been described in the literature but, in general, acute hernias are approached through the linea alba as it enables full abdominal exploration and facilitates the repair, especially for cats with multiple abdominal wall ruptures or when strangulation is expected.3,12 Chronic ruptures without evidence of strangulation, obstruction or further damage may be approached directly over the defect.3,12

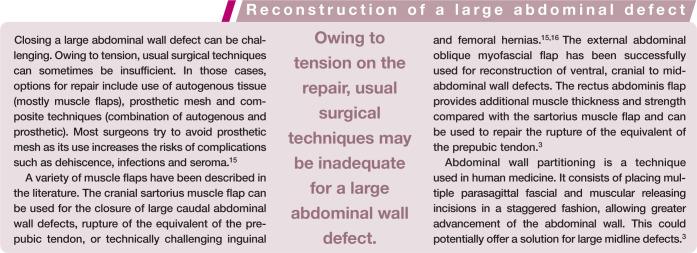

Standard wound care principles are then applied: foreign material removal, debridement of the tissues and lavage. Devitalised/necrotic muscle, fat, fascia and dermal tissue must be carefully debrided and any necrotic organs resected when possible (eg, section of gastrointestinal tract). An active drain may be required to prevent seroma formation where there is significant dead space and in some cases the subcutaneous tissue and skin may need to be left open for daily cleaning and debridement.

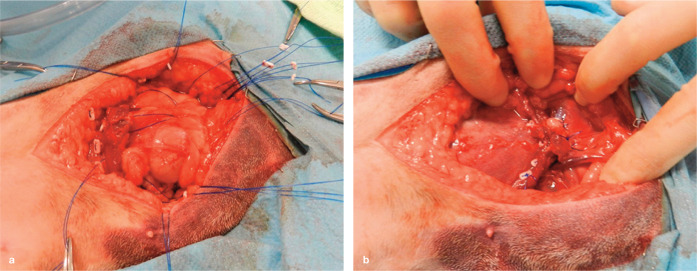

For the repair, synthetic monofilament absorbable sutures such as polydioxanone or non-absorbable sutures such as polypropylene in a tension-relieving (eg, interrupted horizontal or cruciate mattress) suture pattern are usually preferred. The preference of some surgeons for non-absorbable sutures relates to the fact that muscle fascia takes approximately 3 weeks to reach 20% of its original strength after injury and up to a year to regain 80% of its original strength. 15 Generous bites of tissue should be taken. Preplacement of interrupted sutures is the key to a successful repair (Figure 5). If the muscle is friable, a locking loop suture pattern or individual sutures reinforced with buttress material, such as polytetrafluoroethylene (PFTE), may be required to reduce the risk of pull-through. The sutures placed in the deepest part of the wound have to be tied first. Care should be taken to avoid trapping any intra-abdominal structure in the repair.3,15

Figure 4.

Ventrodorsal radiograph of a cat with an abdominal wall rupture. A loss of continuity of the abdominal wall and free abdominal gas can be observed

Figure 5.

Surgical repair of an abdominal wall rupture in the prepubic area in a cat. (a) Preplacement of the sutures; and (b) reconstruction once all the sutures have been tied

Paracostal ruptures are more common in cats than dogs

Some traumatic ruptures require special repair techniques. In cats, for the equivalent of prepubic tendon rupture (see ‘local anatomy’ section) the rectus abdominis muscle can be anchored to the periosteum of the cranial pubic brim. Drilling holes through the pubic brim or passing sutures through the obturator foramen have also been described.3,10,15 It is important to inspect the crura of the superficial inguinal ring as well as the aponeurosis of the external abdominal muscle, as these are commonly affected in cats. Care must be taken not to trap inguinal vessels and nerves.3,8,10,15

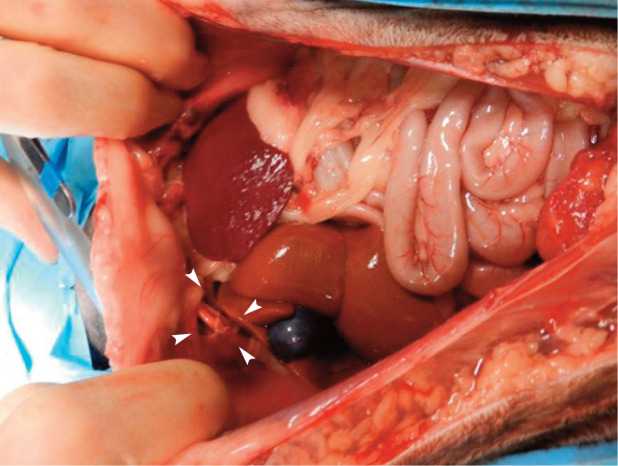

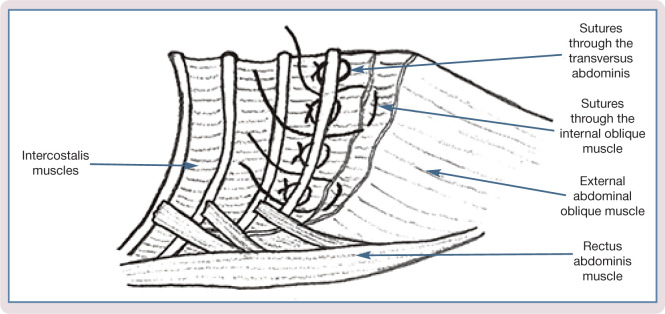

Paracostal ruptures (Figure 6) also require a particular repair technique. They are more common in cats than dogs and involve the origin of the external abdominal oblique and the transversus abdominis muscles, and the insertion of the internal oblique muscle. Abdominal content can sometimes track under the skin or even into the thorax. The repair is performed using the ribs as anchors (Figure 7) with non-absorbable sutures such as polypropylene. As the site is in constant movement due to breathing, recurrence of herniation is common. 4

Figure 6.

Paracostal tear (arrowheads) in a cat

Figure 7.

Paracostal hernia repair. Modified from Williams and Niles 4

Postoperative care and prognosis

The postoperative care depends on the initial injuries. Severely traumatised patients may require intensive supportive care and monitoring. For ambulatory animals, strict exercise limitation for at least 2–4 weeks is required to reduce tension on the repair.

Commonly reported complications include dehiscence, infection, seroma and haematoma formation. Recurrence is generally uncommon, except for paracostal tears where the constant breathing movements increase the risks of further rupture. The overall prognosis depends on the concurrent injuries and is rarely associated with the abdominal wall repair itself.3,5,10,15

Key Points

The most frequent locations in cats for traumatic abdominal wall rupture are prepubic, paracostal, inguinal and dorsolateral.

Traumatic abdominal wall rupture is often associated with concomitant injuries.

A thorough examination and assessment of injuries is key and may require advanced imaging.

Stabilisation, when required, should always be the first priority.

A complete assessment of the abdominal cavity should be made during surgery.

Preplacement of sutures in an interrupted pattern is the key to a successful repair.

The surgeon should be prepared to implement specific repair techniques, dependent on the extent and location of the wound.

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval: This work did not involve the use of animals and therefore ethical approval was not specifically required for publication in JFMS.

Informed consent: This work did not involve the use of animals and therefore informed consent was not required. No animals or humans are identifiable within this publication, and therefore additional informed consent for publication was not required.

Further reading: Boothe, HW. Instrument and tissue handling techniques. In Tobias KM and Johnston SA (eds). Veterinary surgery: small animal. Vol 1, 2nd ed. St Louis, MO: Elsevier, 2018, p 225.

Contributor Information

Julie M Hennet, DVM, MRCVS.

John Williams, MA, VetMB, LLB, CertVR, DipECVS, FRCVS, Vets Now 24/7 Hospital Manchester, 98 Bury Old Road, Whitefield, Manchester M45 6TQ, UK.

References

- 1. Kolata RJ, Johnston DE. Motor vehicle accidents in urban dogs: a study of 600 cases. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1975; 167: 938–941. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Whitney WO, Mehlhaff CJ. High-rise syndrome in cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1987; 191: 1399–1403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Smeak DD. Abdominal wall reconstruction and hernias. In Tobias KM, Johnston SA. (eds). Veterinary surgery: small animal. Vol 2, 2nd ed. St Louis, MO: Elsevier, 2018, pp 1564–1591. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Anderson D. The body wall. In Williams JM, Niles J. (eds). BSAVA manual of canine and feline abdominal surgery. 2nd ed. Quedgeley, Gloucestershire: BSAVA, 2015, pp 45–63. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shaw SP, Rozanski EA, Rush JE. Traumatic body wall herniation in 36 dogs and cats. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2003; 39: 35–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Waldron DR, Hedlund CS, Pechman R. Abdominal hernias in dogs and cats: a review of 24 cases. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 1986; 22: 817–822. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Evans HE. Miller’s anatomy of the dog. 4th ed. St Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Constantinescu GM, Beittenmiller MR, Mann FA, et al. Clinical anatomy of the prepubic tendon in the dog and a comparison with the cat. J Exper Med Surg Res 2007; 14: 79–83. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hall KE, Holowaychuk MK, Sharp CR, et al. Multicenter prospective evaluation of dogs with trauma. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2014; 244: 300–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Friend EJ, White RAS. Rupture of the cranial pubic tendon in the cat. J Small Anim Pract 2002; 43: 522–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lisciandro GR. Abdominal and thoracic focused assessment with sonography for trauma, triage, and monitoring in small animals. J Vet Emerg Crit Care 2011; 21: 104–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pratschke KM. Abdominal wall hernias and ruptures. In Langley-Hobbs SJ, Demetriou JL, Ladlow JF. (eds). Feline soft tissue and general surgery. St Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier, 2013, pp 269–280. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Peterson NW, Buote NJ, Barr JW. The impact of surgical timing and intervention on outcome in traumatized dogs and cats. J Vet Emerg Crit Care 2015; 25: 63–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gibson TWG, Brisson BA, Sears W. Perioperative survival rates after surgery for diaphragmatic hernia in dogs and cats: 92 cases (1990–2002). J Am Vet Med Assoc 2005; 227: 105–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Beittenmiller MR, Mann FA, Constantinescu GM, et al. Clinical anatomy and surgical repair of pre-pubic hernia in dogs and cats. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2009; 45: 284–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mejia S, Boston SE, Skinner OT. Sartorius muscle flap for body wall reconstruction: surgical technique description and retrospective case series. Can Vet J 2018; 59: 1187–1194. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]