Abstract

Case series summary

Gastric diverticulum (GD) is a rare condition that is described adequately in humans but has not been reported in cats. This case series describes six cats with GD, including three that were published in a previous abstract. All cats presented for a variety of gastrointestinal disorders, including chronic vomiting, weight loss and anorexia, and underwent negative contrast radiography to diagnose GD. All but one cat underwent surgical resection of the GD via partial gastrectomy, while the remaining cat was euthanized. Resection of the GD was associated with reduction of reported clinical signs.

Relevance and novel information

Gastric diverticula have never been reported in the cat. Negative contrast radiography appears to be a superior imaging technique in the diagnosis of feline GD. In cats with a vague chronic history, including vomiting, anorexia and weight loss, GD should be considered among the differential diagnoses. Further study and more cases need to be identified to better assess clinical problems referable to GD in the absence of other comorbidities. Maine Coon cats with GD appear to be over-represented.

Keywords: Gastric diverticulum, vomiting, partial gastrectomy, weight loss, pneumoradiography

Introduction

Gastric diverticulum (GD) is defined as an outpouching of the gastric wall.1–3 Gastric diverticula have not been reported in cats.

Gastric diverticula are rare in humans, identified in 0.02% of post-mortem examinations, in 0.04% of upper gastrointestinal (GI) contrast studies and in 0.11% of upper GI endoscopies.3,4 Congenital GD (true GD) are full-thickness diverticula involving all gastric layers that comprise the majority (72–75%) of cases, which most commonly develop in the gastric fundus.1–4 True GD are hypothesized to develop during division of the longitudinal muscle fibers during gestation. The remaining circular muscle fibers form a weak region through which GD can develop. 5 Acquired GD (false GD or pseudodiverticula) do not involve the muscularis layer, are typically found in the antrum and are considered a consequence of other GI disorders such as pancreatitis, neoplasia and gastric obstruction that damage the gastric muscle layers.1,2

The clinical presentation of GD in humans varies from chronic clinical signs of vomiting, nausea, weight loss, epigastric pain, dysphagia and dyspepsia to asymptomatic incidental findings.6,7 Complications are rare but include gastric or peritoneal hemorrhage, bowel obstruction and gastric ulceration and perforation.1,2,7–9 The clinical signs of GD in humans are similar to other GI disorders, and a 1951 review of GD reported that in 61% of cases, clinical signs were attributed to other disorders. 10 This is further complicated by the identification of comorbid GI disease in the majority of cases, and confounds ascription of clinical signs.11,12 Gastric diverticula can be found concurrently with various GI abnormalities, such as gastroesophageal reflux disease and neoplasia.8,13

In humans, the gold standard for diagnosis of GD is reported to be esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD). 7 However, GD can be missed with plain and contrast radiography, EGD and CT imaging.1,2,14 We have found no reports of ultrasonographic diagnoses of GD. Contrast GI studies are traditionally performed in human and veterinary medicine to increase the utility of radiography. Positive contrast radiography is a relatively common procedure in veterinary medicine, but the administration of barium sulfate may be difficult in cats as they are often uncooperative and these studies can be time consuming. 15 In humans, false negatives occur if GD lesions cannot be projected tangentially or if the orifice is small or occluded.12,16,17 Air as a negative contrast agent is a widely recognized but an infrequently used imaging technique in veterinary medicine.16–18 Room air is poorly absorbed by the GI tract, and is typically evacuated passively through the esophagus or aborally. 19 While negative-contrast upper GI study (NCG) techniques require anesthesia, the procedure can be performed quickly on an outpatient basis. Complications are uncommon and include aspiration, gastric rupture, vagally mediated cardiac changes and venous embolism. 18 In cases of upper GI endoscopy, an inflation pressure of approximately 11–18 mmHg is typically needed to open the lower esophageal sphincter to allow the passage of air into the stomach,20,21 while cat stomachs have been demonstrated to distort and rupture at pressures ranging from 90 to 160 mmHg. 22

There are few reports of other feline GI diverticula. An esophageal diverticulum was identified in a cat with a trichobezoar; 23 four cases of intestinal diverticula were noted in a 1991 report; 24 and a single report describes feline intestinal pseudodiverticulosis incidentally identified on exploration for an ovarian remnant. 25

To our knowledge, there are no reports of feline GD and rare reports of other feline GI diverticula.23–25 The purpose of this paper is to describe clinical findings, diagnostic methods and surgical management of six cats with GD, and to emphasize that although GI disease is common in cats, this condition may be underdiagnosed. Further investigation and case-control studies are necessary to determine the best diagnostic approach in, and management of, feline GD.

Case series description

The medical records at a single practice were reviewed between September 2011 and October 2020 for cats with a diagnosis of GD. Data were collected from the medical records, including signalment, history, results of physical examinations, imaging studies performed (including NCG), histologic diagnosis and survival data. All six cats underwent an NCG, which facilitated the diagnosis of GD. Five of six cats underwent partial gastrectomy. Significant comorbidities were also noted in 4/6 cats (see Table 1 for detailed information about each individual case). In the 10 years over which these cats were identified, 547 NCGs were performed in cats presented with clinical signs attributed to GI abnormalities. Additionally, 122 Maine Coon cats were examined at the practice location during that time period, compared with 11,815 non-Maine Coon cats. Three Maine Coon cats were identified to have GD and included in this report. Fisher’s exact test was performed to evaluate the statistical significance of Maine Coon cats with GD.

Table 1.

Information relative to the diagnosis, treatment and follow-up of gastric diverticula in six cats

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 | Case 5 | Case 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Signalment | Age 15 years; MN; Maine Coon cat | Age 9 years; MN; Himalayan | Age 17 years; MN; DSH | Age 10 years; FS; Maine Coon cat | Age 17 years; MN; DSH | Age 13 years; MN; Maine Coon |

| History | Vomiting (3 years); weight loss (3 years); anorexia (1 week) | Vomiting (daily, 3 years); vomiting (twice daily, 4 days) | Anorexia (10 months); vomiting (2 weeks) | Vomiting hairballs (6 years); vomiting without hairballs (1 month) | Vomiting (2 years); weight loss (2 years); anorexia (2 months); chronic kidney disease (2 years) | Vomiting (3 years); aversion to being picked up (2 months) |

| Clinical findings | Temperature 38.3°C; dehydration; abdominal pain | Temperature 38.6°C | Temperature 37.8°C; palpably thickened intestines; abdominal pain | Temperature 38.2°C; dehydration; gastric distension | Temperature 37.7°C | Temperature 37.6°C; palpably thickened intestines |

| Cobalamin, folate, fPL, TLI* | NP | NP | NP | Cobalamin: 354 ng/l (low–normal); folate: 5.3 µg/l; fPL: 4.2 µg/l |

Cobalamin: 185 ng/l; fPL: 9.4 µg/l |

Cobalamin: 260 ng/l |

| Esophagogastroscopy | NP | Unremarkable | NP | NP | NP | NP |

| Abdominal radiography | Outpouching at gastric fundic region; gastric distension | NP | Abnormal gastric distension; irregular gastric shape | Irregular gastric shape | Irregular gastric shape | Ingesta within the stomach despite fasting for 12 h |

| Ultrasonography | NP | NP | NP | No abnormalities | NP | Duodenal muscularis thickening (0.04 cm); ileal muscularis thickening (0.1 cm) |

| Negative contrast upper GI study | Outpouching at the gastric fundus | Outpouching at the gastric fundus; gastric linear opacity | Outpouching at the gastric fundus | Large outpouching along greater gastric curvature at the gastric fundus; smaller gastric outpouching along lesser gastric curvature | Outpouching at the gastric fundus | Outpouching at the gastric fundus |

| Gastric cytology | Unremarkable | Unremarkable | NP | Extracellular rods; Malassezia yeast; polymorphonuclear leukocytes | NP | NP |

| Gastric diverticula histopathology | Atrophy of the muscularis layer; hypertrophy of the muscularis mucosa; segmental reduplication of the muscularis layer | Atrophy of the muscularis layer; hypertrophy of the muscularis mucosa; invagination and infolding of the muscularis layer | Atrophy of the muscularis layer; fibrosis of the muscularis mucosa | Atrophy of the muscularis layer; hypertrophy of the muscularis mucosa | Atrophy of the muscularis layer; ill-defined bundles and fibrosis within the muscularis layer | Atrophy of the muscularis layer; hypertrophy of the muscularis mucosa; hypertrophy of the tunica media arteries |

| Other histopathology, comorbidities | Intestines: inflammatory bowel disease (eosinophilic) Liver: no abnormalities Spleen: no abnormalities |

Intestines: no abnormalities | Intestines: inflammatory bowel disease (duodenum); alimentary small cell lymphoma (jejunum) Pancreas: nodular hyperplasia |

Intestines: no abnormalities Liver: no abnormalities Mesenteric lymph node: no abnormalities |

Intestines: alimentary small cell lymphoma Pancreas: no abnormalities Liver: no abnormalities Mesenteric lymph node: no abnormalities |

Intestines: inflammatory bowel disease |

| Treatment | Gastrotomy with foreign body (trichobezoar) removal; subsequent partial gastrectomy; prednisolone PO 48 months; cyanocobalamin SC 38 months |

Partial gastrectomy ; gastrotomy with foreign body (stick) removal |

NA | Partial gastrectomies (n = 2); cyanocobalamin SC 26 months |

Partial gastrectomy; prednisolone PO 18 months; cyanocobalamin SC 18 months; chlorambucil 17 months |

Partial gastrectomy; dexamethasone sodium phosphate SC 9 months; cyanocobalamin SC 9 months |

| Survival | 48 months (renal cause) | 15 months then lost to follow-up | Euthanized at time of exploratory laparotomy | 26 months then lost to follow-up | 18 months (renal cause) | 9 months at time of writing |

Reference interval (RI) for cobalamin, 290–1499 ng/l; RI for folate, 9.7–21.6 µg/l; RI for fPL, 0–3.5 µg/l (Gastrointestinal Laboratory, Texas A & M College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences).

MN = male neutered; DSH = domestic shorthair; FS = female spayed; fPL = pancreatic lipase immunoreactivity; TLI = serum trypsin-like immunoreactivity; NP = not performed; GI = gastrointestinal; NA = not applicable

All cats presented with a history of GI signs, including ⩾2 years of vomiting (n = 5), anorexia (n = 3) and weight loss (n = 2). Physical examination findings involved non-specific abnormalities such as dehydration and abdominal pain. Esophagogastroscopy was performed in one cat, and no mucosal lesions or gastric abnormalities were noted. Plain abdominal radiography, when performed, revealed an irregular gastric shape and gastric distension in five cats. A single cat (case 6) had ingesta present within the stomach despite a 12 h fast. Abdominal ultrasonography was pursued in two cats, with no gastric abnormalities noted.

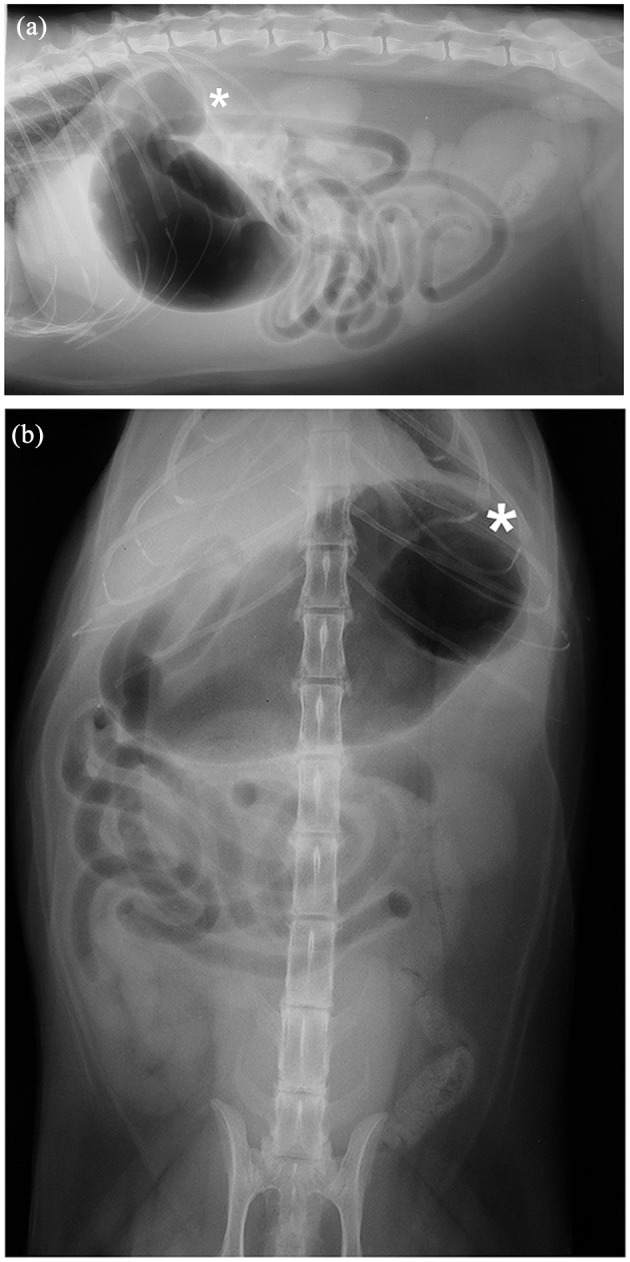

Negative contrast upper GI studies were performed in all cats. The cats were sedated, placed under general anesthesia, intubated and an NCG was performed as follows. A Foley catheter (26 Fr × 30 cm; Bard Medical) was introduced into the esophagus, the cuff was inflated and the catheter was retracted orally so the cuff effaced the caudal aspect of the cricopharyngeal muscle. Approximately 20 ml/kg of air was insufflated into the GI tract via the esophagus, so that upper GI insufflation pressure approximated 10–20 mmHg of room air. Radiography immediately post-insufflation revealed an outpouching at the gastric fundus (Figure 1) in all six cats, supportive of a diagnosis of GD. One cat (case 4) also had an additional gastric outpouching along the lesser curvature noted on the NCG. Gastric mucosal lavage and subsequent gastric cytology was evaluated in three cats, and was either unremarkable (n = 2) or demonstrated the presence of extracellular rods, Malassezia yeast and polymorphonuclear leukocytes (n = 1).

Figure 1.

Case 6, a 13-year-old neutered male Maine Coon cat: (a) left lateral and (b) ventrodorsal radiographs taken immediately post-insufflation during a negative-contrast upper gastrointestinal study. The gastric diverticulum (*) is identified at the gastric fundus, and appreciated on both radiographic views. Incidental spondylosis deformans of the lumbar spine at L3–L4 is also noted

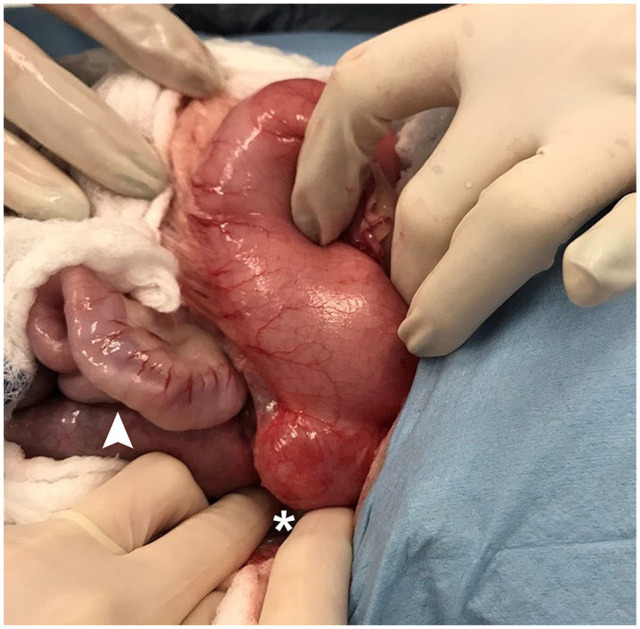

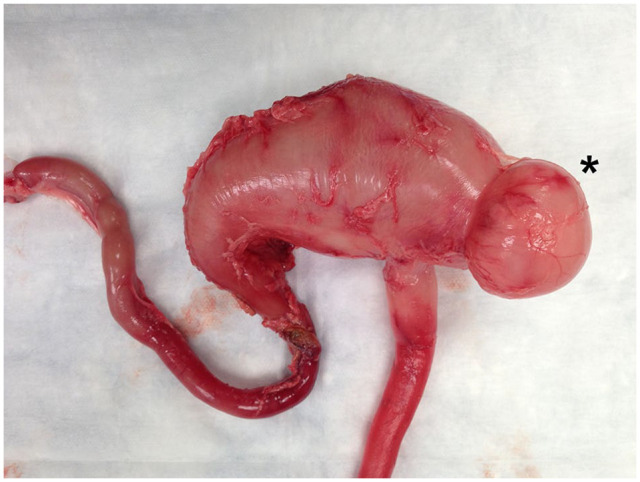

A ventral midline celiotomy was performed in all six cats, which revealed an irregular gastric outpouching at the fundic region (Figure 2) consistent with a GD as identified on NCG. Owing to the presence of other gross abnormalities at the time of laparotomy, the owners of one cat (case 3) declined further intervention and requested euthanasia, and post-mortem examination was performed. In that cat, the GI tract en bloc from the caudal esophagus to proximal duodenum (Figure 3) was submitted for histopathology. The remaining five cats underwent resection of the GD via partial gastrectomy and the resected gastric tissue was submitted for histopathology. Histological examination of all six GD demonstrated atrophy of the muscularis layer, with hypertrophy of the muscularis mucosa (n = 4) and reduplication and fibrosis within the muscularis layer (n = 2) also reported. The five cats recovered uneventfully and were discharged a few days after partial gastrectomy.

Figure 2.

Case 6: intraoperative image of the gastric diverticulum. A 3 cm diameter outpouching of the gastric fundus is appreciated post-insufflation (*) and mild turgidity of the small intestines can be seen (arrowhead). This cat underwent partial gastrectomy to remove the gastric diverticulum, along with full thickness intestinal biopsies, which confirmed inflammatory bowel disease

Figure 3.

Case 3, a 17-year-old, neutered male domestic shorthair cat: post-mortem insufflation photograph of the gastrointestinal tract en bloc from the caudal esophagus to the proximal duodenum. Note the obvious outpouching at the gastric fundus (*), consistent with a gastric diverticulum. Histopathology confirmed a full-thickness gastric diverticulum and concurrent alimentary lymphoma

One month after discharge, weight gain and partial or complete resolution of the vomiting were reported in all five cats. An improvement in appetite was also noted in three cats (case 1, case 4 and case 5), while a single cat was reported by the owners to be more amenable to being picked up (case 6). No recurrence of the GD was noted upon repeat NCG performed on case 1 and case 2 at 2 months and 11 months postoperatively, respectively. Until the time of death or loss to follow-up, all cats demonstrated no recurrence of clinical signs attributable to upper GI disease following resection of the GD.

Survival time was known for two cats (48 months [case 1] and 18 months [case 5] from time of partial gastrectomy), which were euthanized for non-GI morbidities. Two cats were lost to follow-up (15 months [case 2] and 26 months [case 4] from time of partial gastrectomy), while the remaining cat is alive at the time of writing (9 months [case 6]).

Only 6/547 (1%) cats that underwent NCG at the practice over the 10-year period were diagnosed with GD via ante-mortem NCG and confirmed with subsequent surgery and supportive histopathology. Maine Coon cats diagnosed with GD, 3/6 (50%), were over-represented in this study (Fisher’s exact test, P <0.01).

Discussion

Feline GD is an uncommonly diagnosed condition. In humans, the diagnosis is made most reliably with positive contrast radiograph or endoscopy (EGD), with the latter considered the gold standard for diagnosis.1,2,7 The narrow connecting opening in human GD facilitates the diagnosis via EGD, although a small percentage (5%) of cases are missed with this procedure. 10 In this series of cats, all but one had a large diverticulum, which had an opening contiguous with the gastric lumen. This difference may make endoscopy less specific for diagnosing feline GD. No known reported cases of GD in humans or cats have been diagnosed with ultrasound, and of the two cats that underwent abdominal ultrasonography in this report, neither was reported to have any gastric abnormalities. Further investigation is needed to assess the usefulness of ultrasonography in diagnosing feline GD. In this study, NCG was used to better visualize the upper GI tract and make a diagnosis of GD. It is suggested that NCG may be uniquely suited for diagnosing feline GD. All six cats in this report had GD located at the gastric fundus, which is suggestive of the human condition of congenital (true) GD. All these feline GD had similar histopathology, demonstrating involvement of all layers of the gastric wall, including the muscularis layer, further supportive of their similarities in comparison to congenital GD in humans.

There is currently no consensus on the medical and surgical management of GD in humans. Proton pump inhibitors have been utilized for symptomatic therapy, though this does not resolve the underlying pathology. 26 Surgical resection of GD is recommended for large lesions, lesions complicated by bleeding or if a patient remains symptomatic following medical management.1,2,7,27 There is no standardized approach for the medical and surgical management of this condition in cats. As in humans, medical management of symptomatic feline GD with proton pump inhibitors may be a valid approach. However, this is complicated by the fact that the many indicators of GD in humans cannot be reported by non-verbal patients, and thus may be overlooked. Epigastric pain, dyspepsia and nausea are clinical signs which necessarily cannot be reported by feline patients.

Surgical correction of GD via partial gastrectomy has been associated with a good clinical outcome and has been pursued in dogs. A single report of canine GD describes two dogs that presented with chronic vomiting, anorexia and weight loss, and subsequently underwent positive contrast radiography to confirm GD. Both dogs underwent surgical resection of the GD and were reported to make a full recovery postoperatively, though documentation of weight gain and improvement of vomiting frequency was not recorded. 28 In the present study, all cats that underwent surgical resection of the GD were associated with a reduction in vomiting frequency and weight gain. Case 1 and case 6 also had an overall improvement in behavior, and the cats were reported to seek out more attention from their owners. This suggests that surgical management via partial gastrectomy may be a valid treatment option in cases of feline GD.

All cats in this series had a chronic history of vomiting and GI signs and a concurrent GI disorder was identified in 4/6 cats. Inflammatory bowel disease and alimentary lymphoma were diagnosed in those cats via histopathology analyses of intestinal biopsies. In humans, a large proportion of patients with GD have disease of other parts of the GI tract. 10 The demonstration of diverticula in humans and cats with other disorders could be considered coincidental. We suggest that the cats in this study were diagnosed with GD because of the clinical signs of the concurrent GI disorders, and the subsequent diagnostic workup that was pursued. A clinical index of suspicion should be maintained for GD in cats that have a history of chronic GI signs in order to diagnose and effectively manage these cases. More cases need to be identified and evaluated to better assess clinical problems referable to feline GD in the absence of other comorbidities.

Conclusions

This case series identifies that GD is an uncommon condition, which should be considered as a differential diagnosis in cats with chronic GI abnormalities such as chronic vomiting, anorexia and weight loss. Clinical signs of GD in cats may not be readily apparent. This report also highlights the usefulness of negative-contrast radiography to demonstrate feline GD, and may be superior to endoscopy, ultrasound and positive contrast radiography. Maine Coon cats may be predisposed to developing GD.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Lauren Demos BVMS, HonsBSc, DABVP (Feline), and Janette Vani DVM, for their contribution to this manuscript, and Ahmed Elewa PhD for the statistical analysis.

Footnotes

Accepted: 28 May 2021

Author note: An abstract of this paper was presented, in part, at the 2017 AAFP Conference.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval: The work described in this manuscript involved the use of non-experimental (owned or unowned) animals. Established internationally recognized high standards (‘best practice’) of veterinary clinical care for the individual patient were always followed and/or this work involved the use of cadavers. Ethical approval from a committee was therefore not specifically required for publication in JFMS. Although not required, where ethical approval was still obtained, it is stated in the manuscript.

Informed consent: Informed consent (verbal or written) was obtained from the owner or legal custodian of all animal(s) described in this work (experimental or non-experimental animals, including cadavers) for all the procedure(s) undertaken (prospective or retrospective studies). No animals or people are identifiable within this publication, and therefore additional informed consent for publication was not required.

ORCID iD: Kaitlin N Bahlmann  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3716-7878

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3716-7878

References

- 1. Shah J, Patel K, Sunkara T, et al. Gastric diverticulum: a comprehensive review. Inflamm Intest Dis 2018; 3: 161–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rashid F, Aber A, Iftikhar SY. A review on gastric diverticulum. World J Emerg Surg 2012; 7. DOI: 10.1186/1749-7922-7-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gockel I, Thomschke D, Lorenz D. Gastrointestinal: gastric diverticula. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004; 19: 227. DOI: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2004.3339a.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rodeberg DA, Zaheer S, Moir CR, et al. Gastric diverticulum: a series of four pediatric patients. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2002; 34: 564–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Reich NE. Gastric diverticula. Am J Dig Dis 1941; 8: 70–76. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kilkenny JW, 3rd. Gastric diverticula: it’s time for an updated review [abstract]. Gastroenterology 1995; 108: A1226. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Podda M, Atzeni J, Campanella AM, et al. Syncope with surprise: an unexpected finding of huge gastric diverticulum. Case Rep Surg 2016; 2016: 1941293. DOI: 10.1155/2016/1941293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. MaCauley M, Bollard E. Gastric diverticulum: a rare cause of refractory epigastric pain. Am J Med 2010; 123: 5–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Perbet S, Constantin JM, Poincloux L, et al. Gastric diverticulum: a rare cause of hemorrhagic shock. J Intensive Care Med 2008; 34: 1353–1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Palmer ED. Collective review: gastric diverticula. Int Abstr Surg 1951; 92: 417–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Palmer ED. Gastric diverticulosis. Am Fam Physician 1973; 7: 114–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Meeroff M, Gollan JR, Meeroff JC. Gastric diverticulum. Am J Gastroenterol 1967; 47: 189–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Adachi Y, Mori M, Haraguchi Y, et al. Gastric diverticulum invaded by gastric adenocarcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol 1987; 82: 807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Anaise D, Brand DL, Smith NL, et al. Pitfalls in the diagnosis and treatment of a symptomatic gastric diverticulum. Gastrointest Endosc 1984; 30: 28–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Herrtage ME, Dennis R. Contrast media and their use in small animal radiology. J Small Anim Pract 1987; 28: 1105–1114. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Evans SM. Double versus single contrast gastrography in the dog and cat. Vet Radiol Ultrasound 1983; 24: 6–10. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Evans SM, Biery DN. Double contrast gastrography in the cat. Vet Radiol Ultrasound 1983; 24: 3–5. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bowlus RA, Biller DS, Armbrust LJ, et al. Clinical utility of pneumogastrography in dogs. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2005; 41: 171–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lo SK, Fujii-Lau LL, Enestvedt BK, et al. The use of carbon dioxide in gastrointestinal endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 2016; 83: 857–865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ho CM, Yin IW, Tsou KF, et al. Gastric rupture after awake fibreoptic intubation in a patient with laryngeal carcinoma. Br J Anaesth 2005; 94: 856–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lawes EG, Campbell I, Mercer D. Inflation pressure, gastric insufflation and rapid sequence induction. Br J Anaesth 1987; 59: 315–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schulze-Delrieu K. Volume accommodation by distension of gastric fundus (rabbit) and gastric corpus (cat). Dig Dis Sci 1983; 28: 625–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Durocher L, Johnson SE, Green E. Esophageal diverticulum associated with a trichobezoar in a cat. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2009; 45: 142–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ablin LW, Moore FM, Henney LHS, et al. Intestinal diverticular malformations in dogs and cats. Compend Contin Educ Vet 1991: 13: 426–433. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Evers P, Kramek BA, Root MV. Intestinal pseudodiverticulosis in a cat. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 1996; 32: 291–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mohan P, Ananthavadivelu M, Venkataraman J. Gastric diverticulum. CMAJ 2010; 182: E226. DOI: 10.1503/cmaj.090832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fine A. Laparoscopic resection of a large proximal gastric diverticulum. Gastrointest Endosc 1998; 48: 93–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Abidoye EO, Abdurrahman M, Emmanuel EG, et al. Gastric diverticulosis and ulcerations in bitches. Sokoto J Vet Sci 2014; 12: 62–65. [Google Scholar]