Abstract

Practical relevance:

Ocular tumors in cats are seen uncommonly in general practice. Feline ocular post-traumatic sarcomas (FOPTS) represent a very aggressive type of ocular cancer that occurs in cats with a prior history of trauma or severe intraocular disease. Treatment options are limited and early recognition is imperative for close monitoring of disease progression and prompt enucleation.

Clinical challenges:

There is often a delay between the initiating ocular trauma and tumor formation, with an average latency of approximately 6–7 years. Therefore, many cases may not be presented with a documented history of a traumatic incident, especially if the event occurred prior to adoption. While a histologic diagnosis is easy to obtain with enucleation, the aggressive and locally invasive behavior of FOPTS may prevent complete surgical resection.

Global importance:

Cats are the most popular pet in the USA and Western Europe. As there is no breed predisposition for this particular cancer, and males are only slightly over-represented compared with females, a relatively large population of companion animals is at potential risk of developing FOPTS.

Audience:

While uncommon, the understanding and recognition of this tumor type by general practitioners is important for the feline patient. This allows for close monitoring of cats known to have undergone serious ocular trauma, and prompt referral or early enucleation, as well as client education.

Patient group:

The typical patient is a middle-aged to older cat with a history of mechanical trauma to the eye, past intraocular surgery or chronic uveitis.

Evidence base:

Historically, there has been limited clinical evidence upon which to determine the optimal treatment for FOPTS, beyond enucleation of the affected eye. Recommendations are generally based on limited case reports and clinical experience of the practitioner.

Keywords: Sarcoma, cancer, trauma, ocular, enucleation

Introduction

Tumors of the eye are generally rare in cats, but can have devastating consequences for an animal’s vision, appearance and overall comfort. 1 They may even be harbingers of potentially life-threatening disease located elsewhere in the body. By virtue of the location, even benign ocular tumors may cause discomfort and blindness, necessitating surgical removal of the globe owing to local invasion, secondary glaucoma formation, or tissue distortion and/or destruction. 2 Tumors of the eye are categorized as primary tumors originating from the eye itself, or as secondary tumors that have metastasized from another area of the body. The most commonly reported primary tumor of the eye in cats is diffuse iris melanoma, while the most commonly reported metastatic tumor is lymphoma. 3

As vision is a critical sense for humans, there can be a psychological attachment to preserving the eye that should be considered when discussing ocular neoplasia with clients. Many owners see the loss of vision and ocular structures as extremely distressing and often do not realize that companion animals can continue to have an excellent quality of life despite the loss of one, or even both, eyes. Thus, client education remains paramount to ensure potentially life-threatening diseases are explained and addressed in a timely manner.

The purpose of this review is to describe the clinical and histopathological features of feline ocular post-traumatic sarcomas (FOPTS), and to discuss early diagnosis and treatment options. Ocular sarcomas are important for clinicians to know about and understand owing to their malignant potential and association with longstanding ocular disease. 4 However, not all cases of FOPTS are presented with a documented history of ocular trauma or chronic disease; therefore, it is important for clinicians to be cognizant of common presentations and outcomes in order to achieve an early diagnosis and timely implementation of therapy.

Prevalence and risk factors

As reported in the Veterinary Medical Databases (VMDB) in North America over a 10-year period, ocular cancer makes up 0.34% of all recorded feline neoplasms. 3 The actual frequency of ocular neoplasia is undoubtedly higher, as many presumed benign tumors are not submitted for histologic examination. A large database specifically for ocular pathology exists outside the VMDB at the Comparative Ocular Pathology Laboratory of Wisconsin (COPLOW). Within COPLOW’s database (1983–2018), feline submissions make up 12,200 cases, with a total of 6693 submissions (55%) comprising ocular tumors (RR Dubielzig, 2018, personal communication).

Ocular post-traumatic sarcomas were first recognized as a separate disease entity in cats in 1983.4,5 This malignant neoplasm is the third-most common feline primary intraocular tumor following iris melanoma and iridociliary adenoma. 2 Of the 6693 feline submissions to COPLOW from 1983–2018, FOPTS were diagnosed in 560 cases (8.4%) (RR Dubielzig, 2018, personal communication). Among reported cases of FOPTS, there is a common association with ocular trauma and subsequent lens capsule rupture, with chronic intraocular inflammation preceding the development of the tumor.6,7 This disease has also been diagnosed in cats with chronic uveitis, phthisis bulbi or the appearance of an abnormal eye since adoption despite no known history of trauma. Other risk factors for the development of ocular sarcomas in cats are a history of intraocular surgery involving the lens, such as cataract surgery, or globe-sparing chemical cycloablation procedures for glaucoma using intravitreal injections of drugs such as gentamicin (see box below). 8

At this time, viral exposure has not been shown to increase the risk of ocular post-traumatic sarcoma development and, more specifically, no link has been found between FOPTS and FeLV and/or feline sarcoma virus. 9 Initially thought to be a disease entity exclusive to cats, this discrete neoplastic entity has also been reported in rabbits.10,11

History, clinical signs and physical examination

Cats with ocular post-traumatic sarcoma tend to be older adults at presentation, with an average age of 11 and range of 7–15 years; 3 67% of affected cats are intact or neutered males.3,7,12 Rather than reflecting a direct gender predisposition, this over-representation may be due to the behavioral tendency of intact males to fight and thus be at increased risk of ocular trauma. 3 The overwhelming majority of cases reported are domestic shorthair cats; 3 however, this is likely to reflect the popularity of this breed worldwide rather than a true predisposition.

Cats affected by ocular post-traumatic sarcomas typically have a history of a traumatic event pre-dating their presentation, a longstanding history of chronic uveitis, phthisisbulbi and/or have undergone previous intraocular surgery involving the lens.6,7 Although the average time to presentation from the inciting event is approximately 6.2 years, 7 this can range from several months to more than 10 years.1,4,13 Affected cats seldom exhibit signs of pain or irritation as a direct result of the neoplasm;1,13 however, secondary glaucoma, buphthalmos and exposure keratitis are undoubtedly painful and may cause behavioral changes recognizable to the owner. Signs of ocular discomfort include blepharospasm, aggression, decreased appetite, lethargy, hiding and even changes in litter box behavior. In advanced cases, patients may be presented with neurologic signs such as blindness, seizures or mentation changes owing to infiltration of the tumor along the optic nerve and into the brain.4,6,13 Metastatic spread hematogenously to the lungs as well as to the local regional lymph nodes has been reported, but is rare.4,14

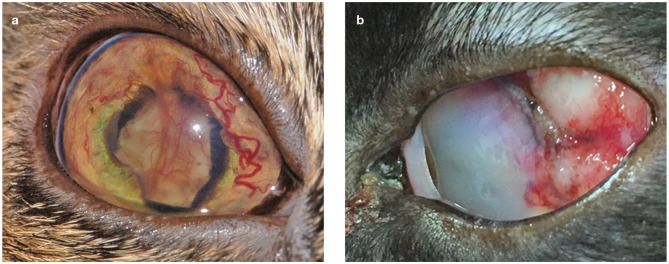

In general, most cats with FOPTS are presented with a change in eye color, owing to corneal opacity, intraocular neoplasm or cataract development. 1 Other presentations may include an abnormally small (phthisical) eye owing to historical trauma and/or chronic uveitis, or an abnormally large (buphthalmic) eye due to secondary glaucoma and/or tumor growth within the eye.1,6,15 The damaged globe undergoes this color change due to tumor infiltration into the cornea and/or proliferation within the anterior chamber of the eye,2,4 both of which can be easily visualized during a routine physical examination. The most commonly observed changes to the affected eye are a white, tan or pink mass filling the chambers of the eye, causing discoloration or a change in the shape of the globe, as already described (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Clinical images of cats with feline ocular post-traumatic sarcomas (FOPTS). (a) A complete cataract with posterior synechiae is causing an abnormal pupil shape (dyscoria). Note the vascular proliferation of neoplastic tissue on the surface of the iris and lens. The majority of the tumor was located in the posterior segment of the eye. (b) A tan/white colored vascular mass is filling the globe and extending through the sclera near the limbus. Images courtesy of (a) Elizabeth Adkins, DVM, MS, DACVO and (b) Brian Marchione, DVM, DACVO

Diagnostic approach

A routine ophthalmic examination is always indicated for feline patients that are presented with vision loss, ocular discharge, globe distortion and/or ocular color change. When performing an ocular examination, it is helpful to evaluate the apparently normal eye first. This will help to establish a normal baseline for that individual animal. General pertinent points of the ocular examination are summarized in the box below.

When cats are suspected of having ocular neoplasia, baseline bloodwork and urinalysis are always indicated to assess their systemic status as well as evaluate for any comorbidities that could influence treatment options and decisions. No changes in baseline bloodwork values are specific to FOPTS. 3 Skull radiographs may demonstrate bone involvement or metallic foreign bodies associated with the previous trauma, but, overall, are not very sensitive or specific for further diagnosis of intraocular neoplasia identified during an ocular examination. 3 By contrast, ocular ultrasound can be very helpful. Although performing the scan is typically relatively straightforward, interpretation of the findings requires training and experience, and therefore referral to an ophthalmologist or radiologist should be considered. Thoracic radiographs are used to evaluate the cardiopulmonary health of the feline patient as well as to assess for evidence of hematogenous metastasis of the tumor.

Advanced imaging with CT and/or MRI may offer superior depiction of the orbit and ocular structures if indicated for assessment of ocular pathology and local invasion of the tumor. These advanced imaging modalities are also useful for treatment planning for cats undergoing surgical resection and/or radiation therapy.

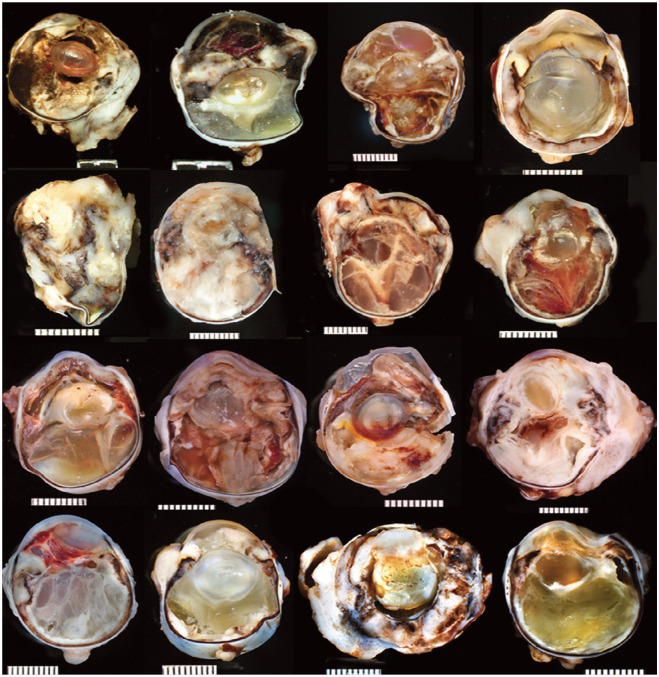

Figure 2.

Post-enucleation photographs of formalin-fixed hemisected globes of 16 cats with the round cell variant of FOPTS. All subtypes have a similar characteristic appearance on gross examination. There is extensive involvement of the intraocular tissues – with circumferential invasion and effacement of uvea and retina, followed by expansion of the tumor within the chambers of the globe, and eventual extension through the sclera and along the optic nerve. Courtesy of Richard R Dubielzig, DVM, DACVP, and COPLOW

Histologic subtypes

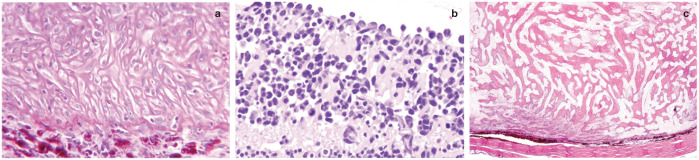

FOPTS are subdivided into three morphologic variants: (1) spindle cell sarcomas, (2) round cell tumors and (3) osteosarcomas/chondrosarcomas (Figure 3 and Table 1). These subtypes cannot be differentiated clinically or grossly and require histologic evaluation. While morphologically different, all three variants have similar biologic behavior.1,18,19

Figure 3.

Histopathologic subtypes of FOPTS. (a) The spindle cell variant comprises fusiform spindle to polygonal cells. There are often periodic acid Schiff (PAS)-positive thick basement membranes, reminiscent of lens capsule, forming around individual cells. Alcian blue/PAS x 40. (b) The round cell variant is comprised of pleomorphic round cells with a large nucleus-to-cytoplasm ratio. Neoplastic cells are infiltrating the inner retina. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) x 40. (c) The osteosarcoma/chondrosarcoma variant comprises mesenchymal cells that demonstrate areas of chondromatous differentiation. Low magnification shows neoplastic osteoid deposition lining the inner pigmented choroid. H&E x 10. Images courtesy of Richard R Dubielzig, DVM, DACVP, and COPLOW

Table 1.

Cases of FOPTS diagnosed at the Comparative Ocular Pathology Laboratory of Wisconsin

| Histologic subtype of FOPTS | Number of cases | Male (%) | Female (%) | Sex unknown (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spindle cell – Early enucleation cases* |

333 54 |

61 54 |

34 44 |

5 2 |

| Round cell/lymphoma – Early enucleation cases* |

122 10 |

70 80 |

28 10 |

2 10 |

| Osteosarcoma/chondrosarcoma | 41 | 46 | 48 | 6 |

| Total/mean percentage | 560 | 62 | 33 | 5 |

FOPTS = feline ocular post-traumatic sarcomas

Early enucleation describes those cases where the globe was likely to have been removed prophylactically owing to concern for a high risk of FOPTS development, and early tumor formation was noted histopathologically

Overall, the spindle cell variant is the most common subtype, and presumed to be derived from lens epithelial cells undergoing transformation to spindle cells after surgical or non-surgical lens trauma.7,19 Although the exact pathogenesis is unclear, there are several features supporting a lens epithelial origin for this variant. 20 For example, early tumors tend to develop around the lens, often extending from regions of lens capsule rupture. Neoplastic cells have differentiation patterns suggesting mesenchymal transition of the original lens epithelium. These neoplastic cells are characterized by a thick, lens capsulelike, basement membrane that stains with the periodic acid Schiff (PAS) method, and can be labeled with vimentin, smooth muscle actin, tumor growth factor beta and basic fibroblastic growth factor. 4 This staining pattern supports the claim that these tumors arise from the lens itself, as normal lens epithelial cells produce a PAS-positive basement membrane, which forms the lens capsule, and have similar staining patterns.4,20

The round cell variant is the second-most common subtype of FOPTS. 7 Neoplastic cells can be labeled with a complex pattern of B and T cell markers, indicating a lymphocytic origin for this tumor subtype.19,21 As lymphoma is often seen in conjunction with chronic uveitis in cats, it is possible this variant represents a form of lymphoma associated with chronic inflammation following a traumatic incident. 21

The osteosarcoma/chondrosarcoma variant is the least common subtype diagnosed.7,19 The cell of origin is currently unknown; however, these tumors are typically characterized by mesenchymal cells that produce cartilage and/or osteoid matrix.14,19,22 Some globes in which the tumor itself does not produce osteoid may have areas of osseous metaplasia instead, which are a common sequela noted with severe ocular trauma.16,23

Therapy

At this time, enucleation is the gold standard of therapy for FOPTS. Thus, it remains important that owners are educated about the increased risk of neoplasia development in cats with eyes that have been traumatized, and those globes that are blind and painful should be removed. 4 Given the propensity for local invasion with this form of neoplasia, as much of the optic nerve as possible should be removed during enucleation. 4 It is important to note that exposure of the optic nerve during enucleation is difficult in cats due to their relatively small orbit and lack of a sigmoid structure to the optic nerve. Excessive rostral traction of the globe to increase surgical exposure or to clamp or ligate the optic nerve is contraindicated in cats as iatrogenic tractional injury to the optic chiasm can result in blindness. 24 Therefore, the authors recommend first removing the globe and then carefully inspecting the orbit to remove any remaining abnormal tissue. This will allow for full histologic evaluation and possible assessment of the extent of disease infiltration. With this information, a prognosis may be more accurately determined and owner expectations managed. The most common life-threatening complication following enucleation is recurrence within the orbit.1,14

Extraocular extension of FOPTS is common, as is recurrence of the tumor, even following orbital exenteration. 12 Unfortunately, owing to the advanced stage at which many of these tumors are first identified and the propensity for early optic nerve involvement, enucleation is often only palliative and may not prolong the patient’s overall survival time.

The authors are aware of no reports in the literature of treatment with radiation, immunotherapy or chemotherapy; therefore, the efficacy of these therapies is unknown. For cats with injection-site sarcomas – a similar type of sarcoma that forms due to chronic inflammation – there have been various attempts at adjuvant treatment and single-agent control with chemotherapy using doxorubicin, carboplatin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, lomustine, mitoxantrone or ifos-famide. 25 Given the developmental similarities of these two tumor types, data generated for injection-site sarcomas may provide a basis for chemotherapy in FOPTS patients. However, further investigations and structured clinical trials would be necessary.

Prognosis

The general prognosis for cats with FOPTS is poor, with an average survival time of 7–11 months.1,15 The prognosis is considerably better for those patients where enucleation is performed before the tumor invades the optic nerve or extends beyond the sclera. Those individuals with extension were found to have reduced life expectancies and tended to die from local invasion and recurrence of their tumors following enucleation. 15 In many cases, there is continued growth along the remainder of the optic nerve into the optic chiasm and brain, which results in loss of vision, other neurologic signs and death. Regional lymph node involvement and pulmonary metastasis have been reported, but are considered rare.1,4,14,26

Owing to the extremely aggressive nature of this tumor, prophylactic enucleation of phthisical or abnormally shaped eyes, those that are blind and severely traumatized, and/or those that are chronically inflamed, may be argued for any feline patient. Extension beyond the sclera or into the optic nerve is common and a poor prognostic indicator, lending further support to early enucleation. Whether early removal will reduce the risk of metastasis and optic nerve infiltration is unknown at present. It is important to educate owners about the increased risk of malignancy in their feline companions that have a history of previously traumatized eyes. This extends to educating owners regarding the contraindication of performing globe-sparing cosmetic procedures such as an evisceration with intraocular prosthesis or ciliary body ablation.4,8

Key Points

Ocular neoplasia is uncommon in companion animals.

A link has not been found between FOPTS and viral agents such as FeLV or FIV.

As ocular post-traumatic sarcomas form in cats with a history of ocular trauma or chronic uveitis, any phthisical or abnormal appearing eye with such a history should be monitored closely and enucleated if blind.

Although rare, FOPTS are a potential complication that should be discussed with clients prior to pursuing cataract surgery or any other globe-sparing cosmetic procedure such as an evisceration with intraocular prosthesis or ciliary body ablation.

Urgent enucleation is advocated as soon as a tumor is noted; however, its effect on long-term survival is not known at this time.

Currently little is known about additional treatment modalities such as radiation therapy or chemotherapy.

Post-traumatic ocular sarcoma is very aggressive and carries a poor prognosis, with few cats surviving long-term following surgical intervention.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr Richard Dubielzig and the Comparative Ocular Pathology Laboratory of Wisconsin for providing information and images from their database, as well as Dr Stephanie Correa and the entire staff at the Animal Cancer Care Clinic of Fort Lauderdale, Florida.

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Contributor Information

Carrissa Wood, Department of Medical Oncology, IndyVet Emergency and Specialty Clinic, Indianapolis, IN, USA.

Erin M Scott, Department of Small Animal Clinical Sciences, College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, USA.

References

- 1. Dubielzig RR, Everitt J, Shadduck JA, et al. Clinical and morphologic features of post-traumatic ocular sarcomas in cats. Vet Pathol 1990; 1: 62–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dubielzig RR. Tumors of the eye. In: Meuten DJ. (ed). Tumors in domestic animals. 5th ed. Ames, IA: John Wiley & Sons, 2017, pp 892–922. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Miller P, Dubielzig RR. Ocular neoplasia. In: Withrow S, Vail D, Page R. (eds). Withrow and MacEwen’s small animal clinical oncology. 5th ed. St Louis, MO, Elsevier, 2013, pp 597–607. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dubielzig RR. Feline ocular sarcomas. In: Ocular tumors in animals and humans. Ames, IA: Iowa State Press, 2008, pp 283–288. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dubielzig RR. Ocular sarcoma following trauma in three cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1984; 5: 578–581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Barrett PM, Merideth RE, Alarcon FL. Central amaurosis induced by an intraocular, posttraumatic fibrosarcoma in a cat. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 1995; 3: 242–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dubielzig RR, Scott EM, De Lombaert MCM, et al. Feline ocular post-traumatic sarcoma (FOPTS), a review of 325 archived cases. Annual meeting of the American College of Veterinary Ophthalmologists; 2012. Oct 17-20; Portland, OR. p 16. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Duke FD, Strong TD, Bentley E, et al. Feline ocular tumors following ciliary body ablation with intravitreal gentamicin. Vet Ophthalmol 2013; 16: 188–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cullen CL, Haines DM, Jackson ML, et al. The use of immunohistochemistry and the poly-merase chain reaction for detection of feline leukemia virus and feline sarcoma virus in six cases of feline ocular sarcoma. Vet Ophthalmol 1998; 4: 189–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dickinson R, Bauer B, Gardhouse S, et al. Intraocular sarcoma associated with a rupture lens in a rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus). Vet Ophthalmol 2013; 16: 168–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. McPherson L, Newman SJ, McLean N, et al. Intraocular sarcomas in two rabbits. J Vet Diagn Invest 2009; 4: 547–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Peiffer RL, Monticello T, Bouldin TW. Primary ocular sarcomas in the cat. J Small Anim Pract 1988; 2: 105–116. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Willis MA, Wilkie DA. Ocular oncology. Clin Tech Small Anim Pract 2001; 16: 77–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Moreira MVL, De Andrade MC, Fulgencio GO, et al. Presumed post-traumatic ocular chon-drosarcoma with intrathoracic metastases in a cat. Vet Ophthalmol 2017; 5: 535–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Perlmann E, Rodarte-Almeida ACV, Albuquerque L, et al. Feline intraocular sarcoma associated with phthisis bulbi. Arq Bras Med Vet Zootec 2011; 3: 591–594. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Grahn BH, Peiffer RL, Cullen CL, et al. Classification of feline intraocular neoplasms based on morphology, histochemical staining, and immunohistochemical labeling. Vet Ophthalmol 2006; 6: 395–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Baba AI, Catoi C. Ocular and otic tumors. In: Comparative oncology. Bucharest: The Publishing House of the Romanian Academy, 2007, pp 1–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dubielzig RR. Ocular neoplasia in small animals. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 1990; 3: 837–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dubielzig RR, Zeiss C. Feline post-traumatic ocular sarcoma: three morphologic variants and evidence that some are derived from lens epithelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2004; 45: 3562. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zeiss CJ, Johnson EM, Dubielzig RR. Feline intraocular tumors may arise from transformation of lens epithelium. Vet Pathol 2003; 4: 355–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Naranjo C, Dubielzig RR. Round cell variant of feline post-traumatic sarcoma: 7 cases. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2007; 48: 3596. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Woog J, Albert DM, Gonder JR, et al. Osteosarcoma in a phthisical feline eye. Vet Pathol 1983; 2: 209–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Groskopf BS, Dubielzig RR, Beaumont SL. Orbital extraskeletal osteosarcoma following enucleation in a cat: a case report. Vet Ophthalmol 2010; 3: 179–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Donaldson D, Riera MM, Holloway A. Contralateral optic neuropathy and retino-pathy associated with visual and afferent pupillomotor dysfunction following enucle-ation in six cats. Vet Opthalmol 2014; 17: 373–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Saba CF. Vaccine-associated feline sarcoma: current perspectives. Vet Med 2017; 8: 13–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Stoltz JH, Carpenter JL, Albert DM, et al. Histologic, immunohistochemical, and ultra-structural features of an intraocular sarcoma of a cat. J Vet Diagn Invest 1994; 1: 114–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]