Abstract

Practical relevance:

Pain assessment has gained much attention in recent years as a means of improving pain management and treatment standards. It has become an elemental part of feline practice with ultimate benefit to feline health and welfare. Currently pain assessment involves mostly the investigation of sensory-discriminative (intensity, location and duration) and affective-motivational (emotional) domains of pain. Specific behaviors associated with acute pain have been identified and constitute the basis for its assessment in cats.

Recent advances:

The publication of pain scales with reported validation – the UNESP-Botucatu multidimensional composite pain scale and the Glasgow feline composite measure pain scale – and species-specific studies have advanced our knowledge on the subject. Facial expressions have also been shown to be different between painful and non-painful cats, and very recently the Feline Grimace Scale has been validated as a tool for acute pain assessment.

Clinical challenges:

Despite recent advances, several challenges still exist. For instance, the effects of disease and sedation on pain scoring/ assessment are unknown. Also, specific painful conditions (eg, dental pain) have not been systematically investigated. The development and validation of instruments for pain assessment by cat owners is warranted, as these tools are currently lacking.

Aims:

This article reviews the use, advantages, disadvantages and limitations of the two validated pain scales, and presents a practical, stepwise approach to feline pain recognition and assessment using a dynamic and interactive process. The authors also offer perspectives regarding current challenges and future directions.

Keywords: Analgesia, pain scoring systems, pain assessment, acute

Why so crucial?

The lack of pain assessment is one of the main reasons why analgesic administration has often been neglected in cats. 1 Without the ability to accurately assess pain, cats may suffer from the sensory-discriminative, affective-motivational, cognitive-evaluative and physiological consequences of pain (see ‘What are we actually assessing?’, page 26). 2 Pain assessment is an elemental part of feline practice, and pivotal to general health and welfare. It should be part of every physical examination (Figure 1), alongside temperature, pulse, respiration (TPR) and nutritional assessment. Though crucial for proper analgesic treatment, pain recognition is not a simple task in non-verbal patients due to their inability to self-report. 3

Figure 1.

Pain assessment should be considered the fourth vital sign, after TPR assessment. Here, abdominal palpation is being performed as part of a cat’s physical examination

Our knowledge of feline acute pain assessment has dramatically improved in recent years with the publication of pain scales with reported validation,4-6 and studies on factors and limitations affecting pain recognition.7-12

What are we actually assessing?

Pain is a very complex experience and is typically said to be characterized by a set of three ‘domains’. Evaluation of the first of these, the sensory-discriminative domain of pain, involves assessment of intensity, location and duration (ie, physical qualities) by means of a thorough physical examination, history, knowledge of specific behaviors and use of a pain scale. The second is the affective-motivational domain, which relates to the emotional consequences of pain. This domain is often assessed in conjunction with the sensory-discriminative domain. 13 Pain scales allow the evaluator to include pain-induced changes in demeanor, such as dullness or aggression.

The affective-motivational domain plays an important role in pain perception in humans, and cats are probably affected in a similar manner. It is thus reasonable to assume that feline friendly handling techniques, and a quiet, clean and warm environment may help to ameliorate aversive aspects of hospitalization and pain (Figure 2).14,15 Finally, the cognitive-evaluative (third) domain of pain relates to the pain experience in the context of previous experiences or knowledge; it is consequently difficult to assess in cats.

Figure 2.

A non-pharmacological therapeutic approach can be easily and cost-effectively incorporated into feline practice. It maximizes comfort and welfare, and minimizes stress, fear and anxiety. Recovery from anesthesia and surgery, for example, should be facilitated by a quiet location and warm and comfortable bedding

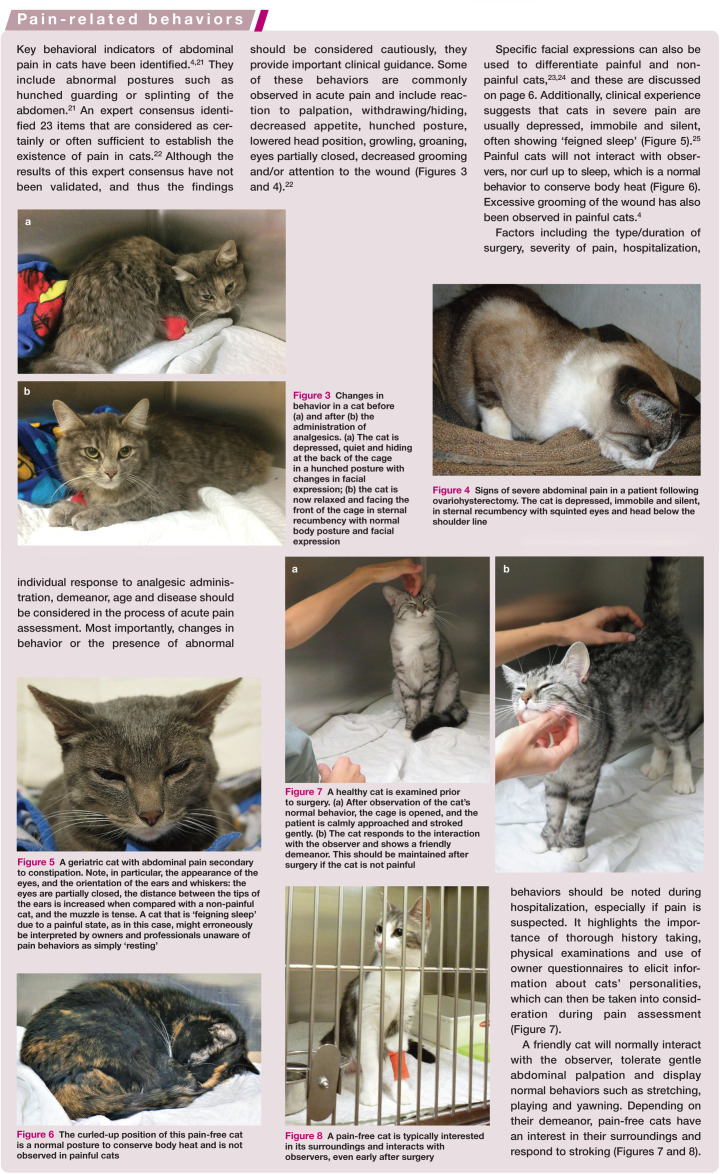

Figure 3.

Changes in behavior in a cat before (a) and after (b) the administration of analgesics. (a) The cat is depressed, quiet and hiding at the back of the cage in a hunched posture with changes in facial expression; (b) the cat is now relaxed and facing the front of the cage in sternal recumbency with normal body posture and facial expression

Figure 4.

Signs of severe abdominal pain in a patient following ovariohysterectomy. The cat is depressed, immobile and silent, in sternal recumbency with squinted eyes and head below the shoulder line

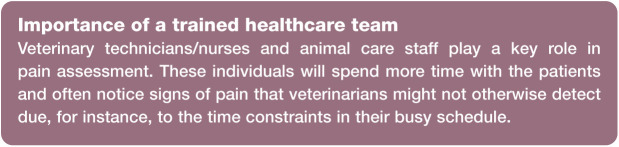

Figure 6.

The curled-up position of this pain-free cat is a normal posture to conserve body heat and is not observed in painful cats

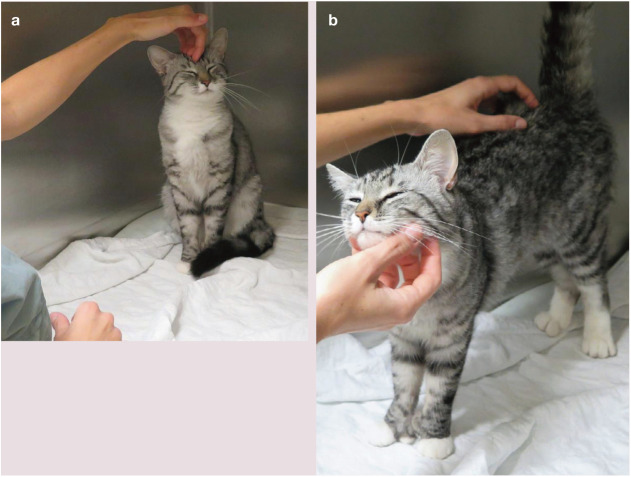

Figure 7.

A healthy cat is examined prior to surgery. (a) After observation of the cat’s normal behavior, the cage is opened, and the patient is calmly approached and stroked gently. (b) The cat responds to the interaction with the observer and shows a friendly demeanor. This should be maintained after surgery if the cat is not painful

Figure 8.

A pain-free cat is typically interested in its surroundings and interacts with observers, even early after surgery

Acute pain assessment by subjective evaluation of changes in behavior

The cat has both physiological and behavioral features that are important in the assessment of pain. However, physiological changes in, for example, heart and respiratory rates, pupil size and neuroendocrine assays (cortisol, glucose, beta-endorphins, etc) are poorly correlated with acute pain in this species;16-19 anxiety, stress and fear will affect these variables, particularly in the hospital setting. 20 For example, anesthesia or bandaging have been shown to increase plasma concentrations of cat-echolamines in non-painful cats.16,17 Therefore, some of these physiological variables might be important in the overall patient/disease evaluation, but not directly for pain assessment. Blood pressure is the only physiological ‘marker’ that has been correlated with increased pain and cortisol concentrations, but its monitoring is not always practical in a busy clinical setting.4,18 Changes in appetite are another important physiological indicator; painful cats have decreased appetite. 4 Conversely, some cats may not eat simply because they are not hungry or are ill. Therefore, pain assessment is mostly performed using subjective behavioral changes, which can often be subtle in cats. Evoked responses (eg, reaction to palpation) via a dynamic and interactive approach with the cat should provide the best assessment. However, cats that are resting should not be disturbed for pain assessment.

Knowledge and observation of pain behaviors (see box on pages 26–27) are therefore fundamental in feline pain assessment.

Feline acute pain scales

Pain scales are clinical metrology instruments that primarily evaluate the behavioral expression of pain. Rigorous validation of these instruments is required before their use is recommended. In brief, the validation process should ensure that the instrument measures what it is intended to measure (validity), produces consistent results when repeated over time (reliability), and is able to detect clinically relevant changes (sensitivity). Ideally, the instrument should be compared with a similar gold-standard tool, if one already exists. 26

In general, pain scales should be practical, user-friendly and easy to implement, independent of who is assessing (technician/ nurse, veterinarian, student or individual under training) or the type of pain (eg, surgical, dental or medical). They should discriminate between different pain intensities (mild, moderate and severe), differentiate painful from non-painful individuals and provide a cut-off point above which interventional (rescue) analgesia is considered (or given) based on solid statistical analysis. 26 Pain scales are important in the repeated assessment of pain as a monitoring tool and for identification of ‘treatment failure’. The advent of validated pain-scoring instruments will undoubtedly improve study design and generate more robust data in feline analgesia.

There are two pain scales that have undergone validation in cats: the UNESP-Botucatu multidimensional composite pain scale (UNESP-Botucatu MCPS) and the Glasgow composite measure pain scale–feline (Glasgow rCMPS-F). 13 The UNESP-Botucatu MCPS is the only instrument to have undergone comprehensive validity, reliability and sensitivity testing. 4 The Glasgow rCMPS-F reported validity and moderate sensitivity, 5 while an updated (‘definitive’) version of the Glasgow rCMPS-F (Glasgow CMPS-Feline) showed improved discriminatory ability (sensitivity). 6 These two instruments have been used in several clinical trials7,8 and are discussed in the boxes on page 28.

Note that other scales are available, including the visual analog scale (VAS), the numerical rating scale (NRS) and various descriptive rating scales such as the University of Melbourne Pain Scale and the Colorado Feline Pain Scale, but these have not been validated and should not be used at this stage for the evaluation of pain in cats. Pain assessment could be misleading.

Limitations and new knowledge

It is natural that pain scales evolve with time as more is learnt about their limitations and further validations are performed.

It is now known, for example, that the UNESP-Botucatu MCPS is influenced by the administration of ketamine-based protocols: 9 specifically, ketamine produces a confounding effect on the ‘psychomotor’ subscale that can lead to false increases in pain scores. These in turn could potentially result in inappropriate administration of rescue analgesia to pain-free cats. 9

Confounding results for both the UNESP-Botucatu MCPS and Glasgow rCMPS-F scales have likewise been described in cats with certain demeanors (ie, shy, or fearful and showing aggressive behavior). 10 In feline practice, these shy or fearful individuals may present high pain scores and it can be difficult to distinguish whether they are truly painful or whether their behavior affects pain assessment (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Pain-scoring systems are affected by demeanor. Shy (a) and fearful cats (b) might present with false increases in pain scores due to their demeanor. Image (b) courtesy of Dr Ryota Watanabe

Pain and dysphoria may be difficult to differentiate using these scales. Dysphoria is usually associated with high doses of opioid administration, and manifests as behavioral changes including resentment to handling, restlessness and agitation, among other negative emotional states. In order to distinguish pain and dysphoria, an analgesic intervention can be administered: a decrease in the observed behaviors suggests the presence of pain (ie, analgesic challenge), whereas no change or worsening of the behaviors suggests dysphoria. In the case of the latter, reversal of the pharmacological agent or administration of a sedative is recommended; opioid analgesic effects will be antagonized with the administration of an opioid antagonist (eg, naloxone). Continuous pain assessment should be performed thereafter.

Another interesting finding has been published recently in a study by the authors’ group using both the UNESP-Botucatu MCPS and Glasgow rCMPS-F scales to evaluate the analgesic effects of gabapentin and buprenorphine in cats. Despite strong or very strong correlation in pain scores between the two pain scales when used by the same observer, the decision regarding the administration of rescue analgesia differed between the scales. 8 In practical terms, one scale indicated the requirement for rescue analgesia for some cats while the other did not. These results are important when considering the study of new analgesic techniques, as they suggest that perceived efficacy of an analgesic drug could be related to the pain scale used for its testing.

Facial expressions and the Feline Grimace Scale

Facial expressions have been used to evaluate pain in different species, and recently they have been incorporated into feline pain assessment. 6 In a previous study, changes in ear and muzzle position had been identified in painful versus non-painful cats (Figure 5). 23 Recently, development of a Feline Grimace Scale revealed further differences between painful and non-painful cats. 24 Five ‘action units’ were identified and included ear position, orbital tightening, muzzle tension, and whiskers and head position (Figure 10). 24

Figure 5.

A geriatric cat with abdominal pain secondary to constipation. Note, in particular, the appearance of the eyes, and the orientation of the ears and whiskers: the eyes are partially closed, the distance between the tips of the ears is increased when compared with a non-painful cat, and the muzzle is tense. A cat that is ‘feigning sleep’ due to a painful state, as in this case, might erroneously be interpreted by owners and professionals unaware of pain behaviors as simply ‘resting’

Figure 10.

Changes in facial expression are good indicators of pain in cats. (a) A 12-year-old male neutered cat prior to dental extractions. The ears are upright, the eyes are wide open, and the whiskers are relaxed. (b) Facial expressions of pain 2 h following full-mouth dental extractions. The distance between the tips of the ears is increased, there is squinting of the eyes and the muzzle is tense. The mouth is also opened and swollen. (c) Thirty minutes after administration of rescue analgesia (hydromorphone) the distance between the tips of the ears has returned to normal, with the ears again in the upright position. The eyes are wide open (mydriasis is secondary to opioid administration) and the whiskers and muzzle are relaxed. Images courtesy of Dr Ryota Watanabe

Very recently this Feline Grimace Scale has been shown to be a valid tool for acute pain assessment. 33 It has displayed good inter- and excellent intra-rater reliability, and discriminates painful from non-painful cats. Current studies are investigating its responsiveness and the cut-off for analgesic administration.

Challenges in clinical acute pain assessment

Various challenges relating to clinical acute pain assessment in cats have been recognized, as listed on the right. A further important challenge and limitation concerns the study population used in investigations on feline analgesia. Published studies commonly involve healthy cats undergoing neutering.27,33 Consequently, it is not known how disease, sedation or pregnancy, for example, affect postoperative pain assessment and scoring in feline practice. 12 Clinically it has been shown that cats with upper respiratory tract disease present changes in facial expressions that are similar to those reported in painful cats (Figure 11) as well as similar body posture, lack of interaction with the observer, reduced appetite and depression. 12 This population of cats may present with clinical signs such as sneezing, ocular discharge, blepharospasm, conjunctivitis, rhinitis and stomatitis, which could be related to pain and/or disease. Therefore, disease might bias pain assessment and the need for rescue analgesia.

Figure 11.

A female cat with upper respiratory tract disease before ovariohysterectomy. The cat was depressed upon presentation and had decreased appetite; note the hunched body posture and ocular discharge. These clinical signs could be interpreted as pain postoperatively

Another type of bias – intrinsic or implicit – refers to attitudes or stereotypes that involuntarily and subconsciously affect our understanding, actions and decisions. Studies have shown that the evaluator’s gender and language can produce intrinsic bias in feline pain assessment. 7 Ideally, the pain-scoring tool should go through back-translation and be validated again in the language of the user to respect cultural semantics. 30 For example, the order of the questions and their relevance in the instrument might change after translation and validation.4,28-31 Clearly, in this respect the UNESP-Botucatu MCPS has an advantage, as it has been published in five languages.

Training also impacts pain assessment. In a recent study, veterinary students recorded lower pain scores than individuals with previous experience in pain assessment. 7 In a separate study, the results of pain assessment differed between veterinary anesthesiologists and graduate veterinarians versus undergraduate veterinary students. 11 Indeed, scores can be significantly different and, depending on who is assessing pain, the outcome for rescue analgesia might change. 7 This also has implications for clinical trials, as the performance of an analgesic drug in this setting might be observer-dependent. 8

Future perspectives

The future for feline acute pain assessment looks to be promising and exciting, as we learn more about specific pain behaviors, and new tools are developed and validated. Some particular perspectives are discussed below.

Studies with cat owners are important and should be addressed. Research has shown that cat owners are able to identify specific behaviors up to 3 days after castration or ovariohysterectomy, with owners reporting a decrease in overall activity level and playfulness, an increase in the amount of time spent sleeping and altered locomotion. 34 Significantly, the pain-related behaviors reported by cat owners were similar to what veterinarians would expect. This highlights the importance and value of client education regarding pain behaviors (what to expect and how to proceed) in order that painful cats are brought into the clinic for appropriate diagnosis and treatment. A useful client education resource is described on page 31.

Behavioral studies are paramount for learning about pain-related behaviors in specific conditions As well as learning about pain-related behaviors in ophthalmic, dental (see below) and neuropathic pain, among others, these studies would corroborate if current pain-scoring instruments are valid in these scenarios. Additionally, behavioral assessment via video analysis may allow discrimination of pain intensity and the study of hitherto unknown pain behaviors, and determine how pain behaviors are affected by the administration of analgesics or treatment of primary disease.

The issue of dental pain in feline practice Global dental guidelines have recently been published by the World Small Animal Veterinary Association (WSAVA) 35 which state that dental pain is under-recognized and undertreated in small animal practice. Periodontal disease produces severe pain, inflammation, dysphagia, sialorrhea, halitosis, weight loss and oral hemorrhage. 35 Some cats will rub or paw at the face, particularly during eating or playing. However, behavioral signs of oral disease-induced pain and the effects of oral pain and its impact on feeding behavior have not been systematically studied in cats. 35 Owners will not usually bring their cat into the clinic unless dental pain is severe, by which stage the nutritional/welfare status of the patient has been dramatically compromised. An ongoing, multidisciplinary study involving nutrition, dentistry, and behavioral and pain management could address this gap in clinical knowledge. These patients present specific pain and feeding behaviors that are different from cats without oral disease. Facial expressions before and after treatment of oral disease and analgesic administration are likewise unique (Figure 10). In the authors’ experience, cats with severe oral disease require up to 96 h of analgesic administration following dental extractions.

Pain scales and use of mechanical nociceptive thresholds can provide means of objective assessment of clinical pain. Mechanical nociceptive threshold testing refers to the use of calibrated devices (ie, algometers) that are applied against parts of the body until a behavioral response is observed (eg, withdrawal, vocalization, escape reaction). The amount of force (ie, grams or newtons) necessary to elicit a behavioral response is measured and considered the mechanical nociceptive threshold. There is an interest in the incorporation of these non-invasive instruments in clinical acute pain assessment. However, results have not been consistent among algometers and other nociceptive devices, and many of these tools lack validity. 27 Further studies on objective measurements of acute pain assessment are warranted.

Key Points

Assessment of acute pain in cats is mostly based on subjective behavioral changes.

Objective assessment is not always practical. With the exception of blood pressure and changes in appetite, physiological changes have not been consistently correlated with acute pain.

Key behavioral indicators of abdominal pain have been identified.

There are two pain scoring instruments for use in cats: the UNESP-Botucatu multidimensional composite pain scale and the Glasgow feline composite measure pain scale.

Facial expressions change in acute pain. These changes should be considered in the evaluation of pain in this species.

Conclusions

Feline acute pain assessment has improved in recent years. Specific pain behaviors have been described and the development and validation of instruments to evaluate pain has made a substantial contribution to this field. However, these tools still have their limitations. Future studies should investigate the effects of disease and sedation on pain assessment and its scoring instruments, and the specific pain behaviors in different states/ diseases. Client education on pain behaviors is also urgently required.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr Ryota Watanabe for video production (supplementary material), and Drs Javier Benito, Ryota Watanabe, Graeme Doodnaught and Marina Evangelista for their key contributions in the study of feline pain management at the Université de Montréal.

Footnotes

Supplementary material: Video 1 Assessment of postoperative pain using the UNESP-Botucatu MCPS in a cat 1 h following ovariohysterectomy. This pain scale provides a clear description of behaviors to be observed. The cat should always be calmly approached, and its reactions carefully monitored. Blood pressure was not evaluated in this example.

Video 2 Assessment of postoperative pain using the Glasgow CMPS-Feline in a cat 2 h following ovariohysterectomy. This pain scale includes scoring of specific behaviors and facial expressions. The cat should always be calmly approached, and its reactions carefully monitored.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Simon BT, Scallan EM, Carroll G, et al. The lack of analgesic use (oligoanalgesia) in small animal practice. J Small Anim Pract 2017; 58: 543-554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Melzack R, Katz J. Pain. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Cogn Sci 2013; 4: 1-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mathews K, Kronen P, Lascelles D, et al. Guidelines for recognition, assessment and treatment of pain: WSAVA Global Pain Council. J Small Anim Pract 2014; 55: E10-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brondani JT, Mama KR, Luna SPL, et al. Validation of the English version of the UNESP-Botucatu multidimensional composite pain scale for assessing postoperative pain in cats. BMC Vet Res 2013; 9: 143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Calvo G, Holden E, Reid J, et al. Development of a behaviour-based measurement tool with defined intervention level for assessing acute pain in cats. J Small Anim Pract 2014; 55: 622-629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Reid J, Scott EM, Calvo G, et al. Definitive Glasgow acute pain scale for cats: validation and intervention level. Vet Rec 2017; 180: 449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Benito J, Monteiro BP, Beauchamp G, et al. Evaluation of interobserver agreement for postoperative pain and sedation assessment in cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2017; 251: 544-551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Steagall P V, Benito J, Monteiro BP, et al. Analgesic effects of gabapentin and buprenor-phine in cats undergoing ovariohysterectomy using two pain-scoring systems: a randomized clinical trial. J Feline Med Surg 2018; 20: 741-748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Buisman M, Wagner MC, Hasiuk MM, et al. Effects of ketamine and alfaxalone on application of a feline pain assessment scale. J Feline Med Surg 2016; 18: 643-651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Buisman M, Hasiuk MMM, Gunn M, et al. The influence of demeanor on scores from two validated feline pain assessment scales during the perioperative period. Vet Anaesth Analg 2017; 44: 646-655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Doodnaught GM, Benito J, Monteiro BP, et al. Agreement among undergraduate and graduate veterinary students and veterinary anesthesiologists on pain assessment in cats and dogs: a preliminary study. Can Vet J 2017; 58: 805-808. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Benito J, Steagall PV. Postoperative analgesia between non-pregnant healthy cats versus pregnant or cats with upper respiratory tract disease. Vet Anaesth Analg 2017; 44: 195.e4. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Merola I, Mills DS. Systematic review of the behavioural assessment of pain in cats. J Feline Med Surg 2016; 18: 60-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rodan I, Sundahl E, Carney H, et al. AAFP and ISFM Feline-Friendly Handling Guidelines. J Feline Med Surg 2011; 13: 364-375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ellis SLH, Rodan I, Carney HC, et al. AAFP and ISFM Feline Environmental Needs Guidelines. J Feline Med Surg 2013; 15: 219-230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cambridge AJ, Tobias KM, Newberry RC, et al. Subjective and objective measurements of postoperative pain in cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2000; 217: 685-690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Smith JD, Allen SW, Quandt JE, et al. Indicators of postoperative pain in cats and correlation with clinical criteria. Am J Vet Res 1996; 57: 1674-1678. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Smith JD, Allen SW, Quandt JE. Changes in cortisol concentration in response to stress and postoperative pain in client-owned cats and correlation with objective clinical variables. Am J Vet Res 1999; 60: 432-436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hoglund O V, Dyall B, Grasman V, et al. Effect of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on postoperative respiratory and heart rate in cats subjected to ovariohysterectomy. J Feline Med Surg. Epub ahead of print 1 November 2017. DOI: 1098612X17742290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Quimby JM, Smith ML, Lunn KF. Evaluation of the effects of hospital visit stress on physiologic parameters in the cat. Feline Med Surg 2017; 13: 733-737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Waran N, Best L, Williams V, et al. A preliminary study of behaviour-based indicators of pain in cats. Anim Welf 2007; 16: 105-108. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Merola I, Mills DS. Behavioural signs of pain in cats: an expert consensus. PLoS One 2016; 11: 1-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Holden E, Calvo G, Collins M, et al. Evaluation of facial expression in acute pain in cats. J Small Anim Pract 2014; 55: 615-621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Evangelista MC, Watanabe R, O’Toole E, et al. Facial expressions of pain in cats: development of the Feline Grimace Scale. Proceedings of the Association of Veterinary Anaesthetists; 2018 March 12-13; St Georges, Grenada, p 61. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Robertson S. Assessment and recognition of acute (adaptive) pain. In: Steagall P, Robertson S, Taylor P. (eds). Feline anesthesia and pain management. New Jersey, USA: Wiley/ Blackwell, 2017, pp 199-219. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Streiner D, Norman G. Health measurement scales: a practical guide to their development and use. 4th ed. Oxford; Oxford University Press, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Benito J, Monteiro B, Lavoie AM, et al. Analgesic efficacy of intraperitoneal administration of bupivacaine in cats. J Feline Med Surg 2016; 18: 906-912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Brondani JT, Luna SPL, Minto BW, et al. Validity and responsiveness of a multidimensional composite scale to assess postoperative pain in cats [article in Spanish]. Arq Bras Med Vet e Zootec 2012; 64: 1529-1538. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Brondani JT, Luna SPL, Crosignani N, et al. Validity and reliability of the Spanish version of the UNESP-Botucatu multidimensional scale to evaluate postoperative pain in cats [article in Spanish]. Arch Med Vet 2014; 46: 477-486. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Steagall PVM, Monteiro BP, Lavoie AM, et al. Validation of the French version of a multidimensional composite scale for evaluating postoperative pain in cats [article in French]. Can Vet J 2017; 58: 56-64.28042156 [Google Scholar]

- 31. Della Rocca G, Catanzaro A, Conti MB, et al. Validation of the Italian version of the UNESP-Botucatu multidimensional composite pain scale for the assessment of postoperative pain in cats. Vet Ital 2018; 54: 49-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Steagall PVM, Taylor PM, Rodrigues LCC, et al. Analgesia for cats after ovariohysterecto-my with either buprenorphine or carprofen alone or in combination. Vet Rec 2009; 164: 359-363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Evangelista M, Watanabe R, Leung V, et al. Construct and criterion validity, and reliability of a Feline Grimace Scale. Proceedings of the World Congress of Veterinary Anesthesiology; 2018 Sept 24-27; Venice, Italy. p 123. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Vaisanen MA-M, Tuomikoski SK, Vainio OM. Behavioral alterations and severity of pain in cats recovering at home following elective ovariohysterectomy or castration. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2007; 231: 236-242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Niemiec B, Gawor J, Nemec A, et al. World Small Animal Veterinary Association Global Dental Guidelines. https://www.wsava.org/Guidelines/Global-Dental-Guidelines (2018, accessed 1 October 2018).