Abstract

Practical relevance:

Procedural sedation and analgesia (PSA) describes the process of depressing a patient’s conscious state to perform unpleasant, minimally invasive procedures, and is part of the daily routine in feline medicine. Maintaining cardiopulmonary stability is critical while peforming PSA.

Clinical challenges:

Decision-making with respect to drug choice and dosage regimen, taking into consideration the cat’s health status, behavior, any concomitant diseases and the need for analgesia, represents an everyday challenge in feline practice. While PSA is commonly perceived to be an uneventful procedure, complications may arise, especially when cats that were meant to be sedated are actually anesthetized.

Aims:

This clinical article reviews key aspects of PSA in cats while exploring the literature and discussing complications and risk factors. Recommendations are given for patient assessment and preparation, clinical monitoring and fasting protocols, and there is discussion of how PSA protocols may change blood results and diagnostic tests. An overview of, and rationale for, building a PSA protocol, and the advantages and disadvantages of different classes of sedatives and anesthetics, is presented in a clinical context. Finally, injectable drug protocols are reported, supported by an evidence-based approach and clinical experience.

Keywords: Acepromazine, agonists of α2-receptors, alfaxalone, benzodiazepines, chemical restraint, ketamine, sedation

Sedation in cats: a routine challenge in feline practice

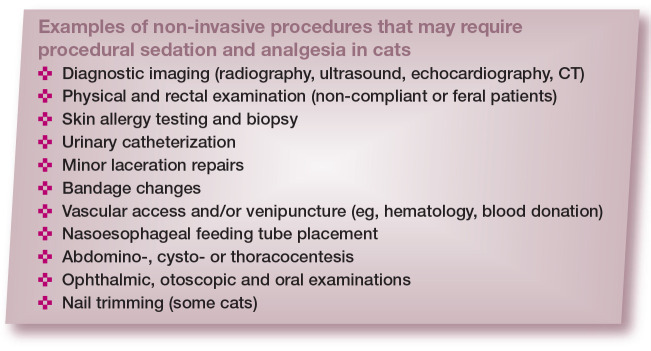

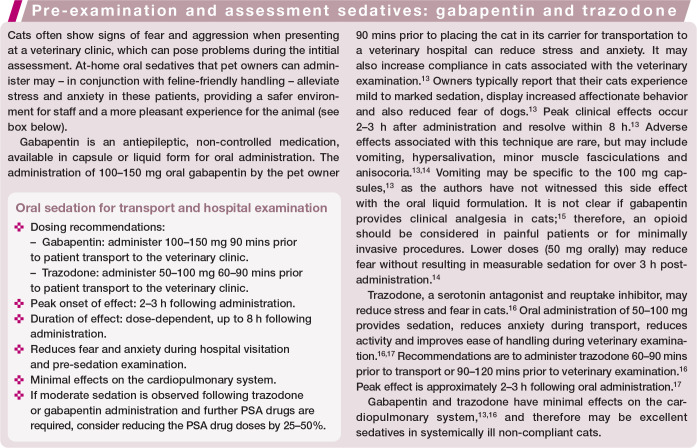

Sedation, chemical restraint and analgesia are part of the daily routine in feline practice. In some cats, especially those with fractious temperaments or showing fearful or excited behavior, sedation is required to render the patient cooperative. It is also used to facilitate diagnostics (eg, venipuncture for hematology, imaging, etc) (see box).

The ultimate goal of sedation is to provide comfort and often analgesia while reducing fear, anxiety and stress in these patients. Sedation will also prevent inadvertent injuries to personnel and promote a better hospital experience for cats undergoing minor procedures. However, the choice of drugs and dosage regimens can be challenging since there is no ‘one size fits all’; protocols should be adjusted and adapted on a case-by-case basis. The clinician must consider the cat’s health status and behavior, concomitant diseases, the need for analgesia, and the magnitude of the procedure and hence the level and duration of sedation required. Other challenges in sedation and analgesia include drug unavailability and lack of familiarity with specific medicines.

Procedural sedation and analgesia (PSA) is a term used in human medicine to describe the process of depressing a patient’s conscious state, in order to perform unpleasant, minimally invasive or objectionable procedures. 1 This clinical review explores the scientific literature to address complications and risk factors, as well as drug protocols used for PSA in cats. Recommendations are made using an evidence-based approach and the authors’ experience.

It’s not ‘just a quick sedation’: complications and risk factors

Sedation is regularly seen as an uneventful procedure with a low risk of complications. However, some protocols used for PSA may induce unconsciousness, amnesia and the loss of protective reflexes (ie, general anesthesia). There may be a mistaken belief that these patients are ‘just sedated’ when they are, in fact, anesthetized, and a more comprehensive monitoring and supportive care plan should be in place given that complications may easily arise. In addition, PSA is not always safer than general anesthesia and is often chosen for its practicality rather than representing the best option for the cat. For instance, general anesthesia offers better airway control and an easy means of ventilation, monitoring and oxygenation when cats are intubated for more extensive and invasive procedures. A study showed that profound sedation may not be suitable for all patients and can increase the risk of anesthesia-related death. 2 Therefore, the decision between PSA and general anesthesia should be taken cautiously, evaluating the advantages and disadvantages of each technique.

Documented risk factors for sedation-related morbidity and mortality are scarce in the veterinary literature.2–4 When risks have been reported, they are often presented in combination with data from anesthetized patients.2,3 This creates difficulty in distinguishing sedation- from anesthesia-specific risk factors. However, one study reported that the risks of mortality following sedation and anesthesia are not significantly different. 3 Extrapolation from previous studies evaluating sedation- and anesthesia-related risk factors can, therefore, provide useful information when determining the likelihood of complications during PSA.

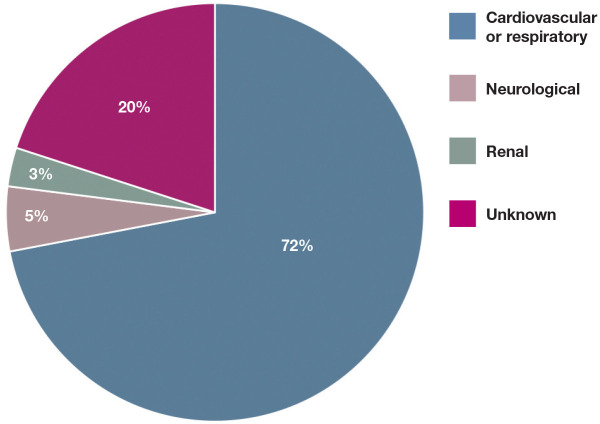

Cats have a higher risk of anesthetic death than dogs.2,3,5–7 The rate of mortality following anesthesia and/or sedation in cats can be as high as 0.24%. 3 The primary causes for anesthesia- or sedation-related mortality in cats are presented in Figure 1. An association between extremes in age and body weight and an increased risk of mortality following sedation and anesthesia has been recognised in cats.2,3 Senior and pediatric patients are more susceptible to the depressant effects of anesthetics, have prolonged recovery due to decreased hepatic blood flow and impaired thermoregulation, and have limited ability to respond to abnormal physiologic states such as hypotension.3,8 Obese patients are not only susceptible to comorbidities due to an enhanced pro-inflammatory state, but they also have reduced cardiovascular reserves and impaired ventilation and mobility due to excessive fat deposition. 3 Intravenous (IV) access, endotracheal intubation and cardio-pulmonary monitoring can be difficult in small cats and kittens. In terms of cat breeds, Himalayans have an increased risk of complications, likely due to their brachy-cephalic conformation, 9 making them prone to respiratory compromise and aspiration pneumonia during anesthesia.10,11 Other risk factors for feline sedation- and anesthetic-related death are detailed in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Primary causes of sedation- and anesthesia-related deaths in cats. From Brodbelt et al (2008) 5

Table 1.

| Risk factors | OR* | |

|---|---|---|

| ASA PS | ASA PS ⩾III vs ⩽II | 3.0–4.0 |

| ASA PS I and II increasing to III | 4.0 | |

| ASA PS III increasing to IV | 3.0–3.7 | |

| ASA PS V vs III | 3.0 | |

| Procedure | Non-elective vs elective | 5.0–6.0 |

| Procedural urgency | 1.6 | |

| Change in urgency status (elective to urgent or urgent to emergent) | 1.6 | |

| Major vs minor procedure | 3.0 | |

| Anesthetic protocol | Premedication + thiopental + isoflurane vs 'other' anesthesia protocols † | 10.0 |

| Endotracheal intubation for minor procedures | 2.0 | |

| Excessive fluid therapy | 4.0 | |

| Lack of pulse oximetry monitoring | 5.0 | |

| Patient demographics | >12 years vs 0.5–5 years | 2.0 |

| <2 kg vs 2–6 kg | 16.0 | |

| >6 kg vs 2–6 kg | 3.0 | |

| Himalayan breed | 4.0 |

ASA PS = American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status

Odds ratio (OR) in this context is the odds that death will occur given a particular condition or circumstance. An OR >1 indicates increased occurrence of mortality

‘Other’ included induction agents other than thiopental, propofol or ketamine alone and maintenance with agents other than isoflurane. For example, use of fentanyl, isoflurane, benzodiazepines or etomidate, or ketamine or thiopental with a coinduction agent

Fluid therapy may be required during PSA. The administration of inappropriate quantities of IV fluids has been found to significantly increase the likelihood of anesthesia- and/or sedation-related deaths in cats. 3 Guidelines for maintenance fluids rate during anesthesia have been published in cats, recommending a significantly lower rate than previously suggested (3–5 vs 5–10 ml/kg/h). 12 Inappropriate use of IV fluids in euvolemic patients can result in volume overload and the development of pulmonary and peripheral edema. A thorough evaluation of the patient’s hydration status and estimated losses during the procedure should help guide the veterinarian in determining if IV fluids are required, and the type and rate of administration to compensate for any ongoing losses and dehydration.

Lastly, fasting may reduce the risk of regurgitation and aspiration pneumonia and, in turn, the sequelae of desaturation, hypoxemia, sympathetic activation and potentially death (see ‘patient assessment and preparation before PSA’). Veterinarians should thus avoid or minimize regurgitation and consider general anesthesia with intubation of the trachea in cats with severe central nervous system, respiratory, cardiovascular or gastrointestinal disorders.

Patient assessment and preparation before PSA

Preanesthetic assessment should be performed in cats before PSA as it may identify potential risk factors and avoid complications. It is not uncommon for a procedure to start under PSA and evolve into a more complex anesthetic challenge. There is a particular problem when procedures become significantly more painful and inadequate analgesia (eg, a weak opioid analgesic) has been administered as part of the PSA protocol. In these circumstances, alternative analgesic agents may be required as the weaker opioids (eg, butorphanol or buprenor-phine) may negatively impact the analgesic efficacy of pure opioid agonists (eg, morphine, methadone and hydromorphone).18,19

The patient’s identification should be confirmed and its medical history reviewed, focussing on previous procedures, and any concomitant medications and diseases. This is also the time to discuss with clients the risks associated with PSA and the planned procedure. Some cats may need fluid therapy and stabilization before PSA; fasting protocols should be in place. Current recommendations include shorter fasting times (3–4 h) when compared with dogs. 20 The administration of a small amount of wet food 3–4 h before sedation may reduce gastroesophageal reflux and acidic reflux. 20 Water should be available until the time of PSA. Specific developmental stages (neonatal, pediatric) and conditions such as gastrointestinal and central nervous system disease or diabetes, brachycephalic conformation or a history of gastroesophageal reflux and/or aspiration may require specific fasting times based on the patient’s individual needs, and further information can be found elsewhere. 21

The assignment of American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status is important to predict complications and identify the risk of anesthetic-related death (Table 1).2,3 Feline-friendly handling techniques should always be adopted (gentle approach, patience, positive attitude, appropriate petting, etc) (Figure 2). Cats with a timid or fearful demeanor should be examined in their carriers; top- or side-opening carriers provide a safe and secure environment for these individuals (Figure 3). Indeed, the cat’s behavior is important in the decision-making process involving PSA and dosage regimens. Blood collection for additional laboratory diagnostics (ie, hematology and blood chemistry analysis), if needed, can be performed after drug administration and during venous catheterization. The authors will often use the blood extracted from the catheter hub to perform a hematocrit and total protein evaluation and avoid unnecessary jugular veni-puncture. However, venous catheterization may not always be performed as part of the PSA protocol and there is no consensus on the administration of fluid therapy in these cats. Additionally, hematocrit values in some cases may decrease by up to 30% after the administration of sedatives, especially dexmedetomidine, ketamine and acepro-mazine.22,23 (Clinicians should also be aware of the potential for increased ultrasonographic and radiographic splenic measures after the administration of acepromazine; 22 and several drugs used during PSA may change echocar-diographic results, as discussed later.)

Figure 2.

Feline-friendly handling techniques should be used throughout procedural sedation and analgesia (PSA) to minimize stress and fear and provide a good hospital experience. The mantras ‘less is more’ and ‘go slow to go fast’ are true during feline handling. Towels can be used around the neck and body for physical restraint and gentle care, and to avoid scruffing. An Elizabethan collar will provide additional protection for the handler from aggressive cats. This particular patient is safely restrained for a procedure such as intramuscular injection or intravenous catheter placement

Figure 3.

Cats may be examined and handled in top-opening or side-opening carriers to facilitate the procedure and maximize comfort during veterinary consultations

Materials, supplies and equipment should be ready and in good order before PSA. Prevention is key to avoiding complications. Doses and volumes of emergency drugs should be calculated beforehand. It is good practice to have an anesthetic machine and means of intubation and ventilation available when sedation is profound, with a risk of regur-gitation and aspiration, and/or with patients that are at high risk of complications (ie, senior or pediatric patients, or those with extremes of body weight) (Figure 4).2–4 In some practices, an anesthetic machine may not be available. Oxygenation may still be required, and portable oxygen cylinders should be available. Oxygen supplementation may be needed to prevent or treat hypoxemia in cats undergoing PSA. 24 A manual resuscitation bag is a practical means of providing oxygenation (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Supplies prepared in advance of PSA, in case intubation of the cat’s trachea is required. a = cuffed endotracheal tube; b = cuff inflation syringe; c = lidocaine with a syringe and catheter for topical application on the arytenoids to prevent laryngospasm during intubation; d = topical eye lubrication; e = sterile endotracheal tube lubrication; f = roll gauze for securing the endotracheal tube in place; g = mask for oxygen supplementation; h = square gauze to help grasp the patient’s tongue during intubation; i = laryngoscope; j = stylet for placement within the endotracheal tube; the stylet should be introduced only as far as 3–5 cm past the arytenoids, and is removed once the endotracheal tube is in place, taking care not to cause pharyngeal or tracheal trauma; k = manual resuscitation bag and attachment for oxygen insufflation. Note: A Mapleson D (Bain) non-rebreathing circuit attached to an anesthetic machine may be used in lieu of a manual resuscitation bag at flow rates of 150–300 ml/kg/min

Hypothermia can be avoided by using a warming system (ie, forced air warming blanket or circulating warm water device) to prevent heat losses during PSA. Additional measures for the prevention of hypothermia include use of bubble wrap, blankets and quilts, or the Hibler’s method. The last is a low-cost technique combining an outer vapor barrier (ie, plastic wrapping) with an inner insulating layer (ie, blankets). 25 In humans, the Hibler’s method has been shown to reduce hypothermia and promote faster rewarming than use of blankets and bubble wrap. 25

Drug protocols for PSA: overview and rationale

Before focussing on specific injectable protocols for PSA, some important principles deserve particular mention. Firstly, patient assessment incorporating health status and behavior is paramount when choosing a drug protocol for PSA. So too is an individualized approach, allowing adjustments to doses and protocols as required. The ideal protocol should maintain appropriate cardiorespiratory function while unpleasant, minimally invasive procedures are performed. What constitutes ‘appropriate’ for each cat undergoing PSA is vague. For example, a healthy cat may tolerate decreases in cardiac output and heart rate induced by agonists of alpha(a)2-adrenergic receptors during hip radiography. Similar changes in cardiovascular function could, however, be severely detrimental in a senior cat with sepsis and undergoing abdominal ultrasonography.

When possible, neuroleptanalgesia is recommended during PSA and involves the combination of an opioid analgesic and a tranquillizer (ie, acepromazine) or sedative (benzodiazepine). 26 This has the potential benefits of producing a greater degree of sedation and analgesia with reduced adverse cardio-pulmonary effects when compared with either drug administered alone at similar doses. Clinical judgment is important in the decision-making process and antagonist agents (ie, atipamezole, flumazenil or naloxone) should always be available and drawn-up ready for use in critical cases. Butorphanol has been reported to preserve analgesia better than naloxone when used as a reversal agent in cats. 19

Acepromazine, benzodiazepines (ie, diazepam or midazolam) or agonists of α2-adrenergic receptors (ie, dexmedetomi-dine, medetomidine or xylazine) are used in combination with an opioid for PSA (Table 2). Local anesthetic blocks are not specifically discussed in this article, but should be incorporated to provide a smooth PSA while decreasing drug requirements.

Table 2.

Examples of neuroleptanalgesia protocols used for procedural sedation and analgesia (PSA) in cats. 27 If necessary, these suggested protocols can be used for premedication prior to induction of general anesthesia

| Drug combination | Dose (mg/kg) and route * | Comments | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dexmedetomidine combinations for cats ASA PS I-II | Caution in critically ill patients and those with bradyarrhythmias. Low doses may be beneficial in patients with left ventricular outflow obstruction and HCM. Useful in procedures when heavy sedation is required | ||

| Dexmedetomidine + butorphanol | 0.01 + 0.2 IM | Provides good sedation for non-invasive diagnostic procedures (radiography, ultrasound examination, and thoraco-, cysto- and abdominocentesis), phlebotomy, intravenous catheter placement, minor procedures or procedures that result in mild pain in healthy cats. Provides minimal analgesia | |

| Dexmedetomidine + buprenorphine † | 0.01 + 0.02 IM | Provides good sedation and mild to moderate analgesia for the above procedures | |

| Dexmedetomidine + hydromorphone or methadone ‡ | 0.01 + 0.1 or 0.5 IM | Provides excellent sedation and analgesia for the above procedures and for procedures that result in moderate to severe pain | |

| Dexmedetomidine + hydromorphone or methadone + ketamine | 0.01 + 0.1 or 0.5 + 3 IM | May produce profound sedation. Provides excellent analgesia for the above procedures and for procedures that result in moderate to severe pain. May produce some dysphoria during emergence from sedation. Ketamine may elicit pain on injection. Caution when using ketamine in cats with HCM due to its sympathomimetic effects on heart rate | |

|

Acepromazine combinations for cats

ASA PS I-II |

Caution in hypovolemic, critically ill or hypotensive patients. Better suited to more protracted procedures due to its long duration of action and lack of reversibility | ||

| Acepromazine + butorphanol | 0.05 + 0.2 IM | Mild sedation for non-invasive diagnostic procedures (radiography, ultrasound examination), phlebotomy, intravenous catheter placement | |

| Acepromazine + buprenorphine † | 0.03 + 0.02 IM | Good analgesia for procedures that result in mild to moderate pain. Euphoria rather than sedation may be present | |

| Acepromazine + hydromorphone or methadone ‡ | 0.03 + 0.1 or 0.5 IM | Mild sedation as described for the other acepromazine combinations. Good analgesia for procedures that result in moderate to severe pain | |

| Other combinations | |||

| Midazolam + butorphanol + ketamine | 0.3 + 0.3 + 5 IM | Effective chemical restraint for fractious cats ASA PS III or IV. Minimal effects on the cardiovascular system. Does not always produce profound sedation and vocalization may be present; however, patients are often compliant for most minor procedures. Ketamine may elicit pain on injection. Caution when using ketamine in cats with HCM due to its sympathomimetic effects on heart rate. Alfaxalone (2–3 mg/kg) can replace ketamine. Oxygen supplementation and endotracheal intubation equipment should be available when using injectable anesthetics | |

| Methadone or hydromorphone* + midazolam | 0.5 or 0.1 + 0.25 IM | Provides adequate sedation in pediatric (<12 weeks), senior (>75% normal life expectancy for the breed) or ASA PS >IV patients. u-opioid receptor agonists can be replaced with butorphanol or buprenorphine for non-painful or mildly painful procedures, respectively | |

If additional doses of PSA drugs are required due to decreases in depth of sedation, the authors recommend administering 25–50% of the original dose

Buprenorphine at standard concentration (0.3 mg/ml)

Other full μ-opioid receptor agonists can be used (ie, fentanyl, oxymorphone, morphine)

ASA PS = American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status; HCM = hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; IM = intramuscularly

Note that alternative methods for achieving PSA, such as chamber induction using inhalant anesthetics, can be useful to protect handlers from injury but may cause airway irritation 28 and an excitatory phase in patients, 29 in addition to the environmental concerns over waste anesthetic gases. 30 Moreover, this technique may be associated with increased risk of anesthetic-related morbidity or mortality due to the excessive inhalant anesthetic concentrations required to induce adequate sedation and avoid involuntary excitement. 20

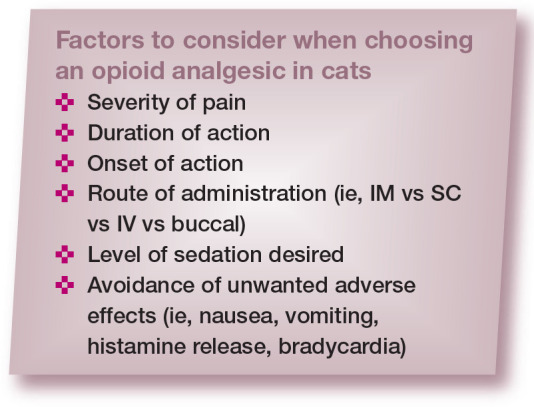

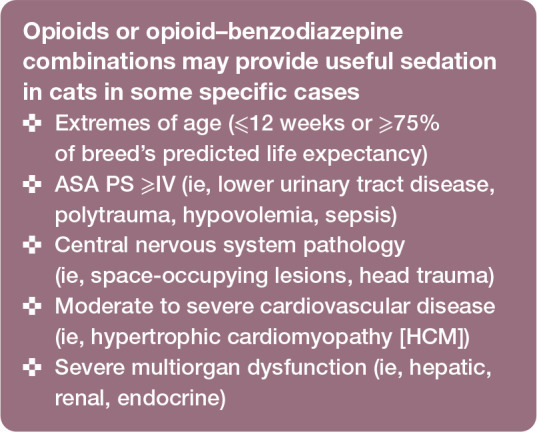

The magnitude/level of sedation and analgesia and the quality of recovery are better with the combination than with each drug used alone;31,32 lower doses of each drug can normally be administered. Also, adverse effects may be reduced with neuroleptanalgesia. For example, in a prospective, randomized, blinded study of 30 cats, the prevalence of vomiting was 70% when dexmedetomidine was used alone, compared with 10% after dexmedetomidine-butorphanol. 33 The dose of single-agent dexmedetomidine also had to be increased two-fold to produce similar sedative effects to a combination of dexmedetomidine with butorphanol or meperidine (pethidine) for various clinical procedures. 33 However, there are some occasional cases where opioids are used alone for PSA or when the specific combination of benzodiazepine-opioid is indicated (see box on right). The specific choice of opioid will depend on the onset, duration and level of analgesia required for the procedure (see box on left; Table 3). For further information, readers are referred elsewhere.18,34–36

Table 3.

Opioids commonly used for procedural sedation and analgesia in cats 34

| Opioid | Dose (mg/kg) | Frequency of administration | Route of administration | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pure μ-opioid receptor agonists | For moderate to severe pain relief | |||

| Methadone | 0.3–0.5 | q4–6h | IM, IV, OTM | Has NMDA receptor antagonist properties |

| Hydromorphone | 0.05–0.1 | q4–6h | IM, IV | Hyperthermia may be observed. Vomiting observed with IM route |

| Morphine | 0.2–0.4 | q4–6h | IM, IV | Slow administration is recommended with IV route due to potential for histamine release. Histamine release is dose-dependent. Vomiting may be observed with IM route |

| Oxymorphone | 0.025–0.1 | q4–6h | IM, IV | – |

| Fentanyl | 0.002–0.01 | q20–30 mins | IV | May produce more pronounced cardiopulmonary depression than other opioids. Consider as a CRI (2–15 (jg/kg/h) for procedures longer than 30 mins |

| Meperidine (pethidine) | 3–5 | q1–2h | IM | Do not administer IV due to histamine release. May produce increases in heart rate |

| Partial u-opioid receptor agonists | Provide mild to moderate pain relief | |||

| Buprenorphine 0.3 mg/ml | 0.02–0.04 | q4–8h | IM, IV, OTM | May produce euphoria |

| Buprenorphine 1.8 mg/ml | 0.24 | q24h up to q3 days | SC, OTM | For the treatment of postoperative pain. Not recommended for short procedural sedations |

| Weak u-opioid receptor agonist or u-opioid receptor antagonist/ K-opioid receptor agonist | Provides minimal pain relief |

IM = intramuscular; IV = intravenous; OTM = oral transmucosal (buccal); NMDA = N-methyl D-aspartate; CRI = constant rate infusion; SC = subcutaneous

Sedation is superior when agonists of α2-adrenoreceptors are administered alone or in combination with opioids when compared with acepromazine alone or with an opioid, and also benzodiazepinebased protocols.22,23 Ketamine, tiletamine– zolazepam and alfaxalone-based protocols have also been used for neuroleptanalgesia to provide robust chemical restraint (Table 4). However, sedative effects may vary according to dosage regimens, individual patient variability in response to the drugs, disease and patient behavior, and the quality of sedation is sometimes unpredictable.

Table 4.

Selected drug protocols used in published studies for procedural sedation and analgesia (PSA) in cats

| Drug combination | Doses, route of administration, procedure/endpoint | Comments | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tiletamine-zolazepam + methadone (TZM) | 3 mg/kg + 0.2 mg/kg IM; before neutering | Better restraint for venous catheterization and higher sedation scores than acepromazine (0.03 mg/kg) and methadone (0.2 mg/kg) (AM) IM but similar HR and RR 25 mins after injection Similar anesthetic-sparing effect during neutering and time to extubation and sternal recumbency to AM. Time to standing longer with TZM |

37 |

| Tiletamine-zolazepam (TZ) | 5 mg/kg or 7.5 mg/kg buccally; no endpoint | 0.1 ml/kg or 0.15 ml/kg, respectively, of the combination is administered into the cheek pouch. Onset and duration of action are approximately 15 mins and 120 mins, respectively Sedative effects were not significantly different and there seems to be no benefit in using high vs low doses of TZ alone buccally, especially considering that systolic BP and RR were lower in high- vs low-dose Tz Hypersalivation was observed in 3/7 cats with the high dose of TZ Dysphoria was observed in the recovery phase but not thoroughly reported |

38 |

| Tiletamine-zolazepam + ketamine + xylazine (TKX) | 500 mg TZ (1 vial) reconstituted with 4 ml ketamine (100 mg/ml) and 1 ml xylazine (100 mg/ml) IM; before neutering | Cats were administered 0.25 ml of the TKX solution IM Monitor closely for hypoxia as SpO2 fell below 90% in most cats Prolonged recoveries even when reversed with yohimbine (72 ± 42 mins from reversal to sternal recumbency) Patients may require additional analgesia for more painful procedures |

39 |

| Acepromazine + butorphanol ± ketamine (AB or ABK, respectively) | 0.1 mg/kg + 0.25 mg/kg ± 1.5 mg/kg IM; echocardiography | Sedation scores or quality of sedation were not recorded Increases in HR seen after ABK and decreases in BP after AB Changes in echocardiographic variables were not deemed clinically relevant, except for decreases in preload and increases in diastolic wall thickness that could be mistaken for hypertrophy (ie, pseudohypertrophy) |

40 |

|

Alfaxalone ± dexmedetomidine

(AD) |

5 mg/kg ± 20 jg/kg IM; no endpoint | High volume of administration may be an issue with IM injection Moderate to profound sedation with alfaxalone alone, suggesting robust chemical restraint with minor cardiorespiratory changes General anesthesia is achieved with AD in a dose-dependent manner. All cats could be intubated with the combination. Decreases in HR and increases in BP were observed with AD. Desaturation can be recorded with high-dose dexmedetomidine Some adverse effects may be observed in the recovery phase: alfaxalone can produce ataxia and dysphoria; vomiting, ataxia and hyperkinesia may be observed with the AD combination |

41 |

| Alfaxalone | Doses of 1, 2.5, 5 and 10 mg/kg (IM) or 5 mg/kg (IV); no endpoint or 2 or 5 mg/kg IM; diagnostic or non-invasive procedures |

Large volumes required for IM injections, especially in the 5 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg groups Time to lateral recumbency was less than 7 mins in all cats, except for the 1 mg/kg group. Dose-dependent duration of sedation was observed, with lateral recumbency for more than 1 h in the 5 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg groups Poor anesthetic recovery with ataxia, muscle tremors, paddling and opisthotonos precludes the use of alfaxalone as a single sedative agent in feline practice Inadequate sedation was recorded for both 2 mg/kg and 5 mg/kg alfaxalone in 10 cats and these animals were excluded from the trial |

24, 42 |

| Dexmedetomidine ± hydromorphone + alfaxalone (DHA or DA, respectively) | 10 jg/kg ± 0.1 mg/kg + 5 mg/kg IM; endotracheal intubation | Both protocols induced light depth of anesthesia according to bispectral index monitoring. Large volumes of alfaxalone are injected IM Time to loss of withdrawal reflex and intubation was shorter in cats receiving DH than D before alfaxalone. All cats were intubated when using both protocols. Spontaneous movement during light anesthesia Prolonged recovery, marked hyperactivity, excitement and ataxia were observed in both the DA and DHA groups. Quality of recovery was not improved with the addition of hydromorphone |

43 |

| Alfaxalone + butorphanol (AB) | 2 mg/kg + 0.2 mg/kg IM; echocardiography or diagnostic/non-invasive procedures or venipuncture for blood collection or 5 mg/kg + 0.2 mg/kg IM; diagnostic/non-invasive procedures or 2–3 mg/kg + 0.4 mg/kg IM; venipuncture for blood collection or 2–3 mg/kg + 0.2 mg/kg SC; oral radioiodine administration |

Onset and duration of lateral recumbency were 5–10 mins and 35 mins approximately, respectively. Time to standing was around 45 mins. Good for outpatient procedures Median recumbency time was 53 mins after AB for blood collection AB produced chemical restraint with some mild systolic depression (decreased left ventricular fractional shortening and ejection fraction) AB produced similar sedation to dexmedetomidine (10 Mg/kg) and butorphanol (0.2 mg/kg; DB) IM. Muscle relaxation was better with DB than AB Cats that did not achieve lateral recumbency with either DB or AB tolerated gentle physical restraint for blood collection Quality of recovery was similar for DB and AB High volumes of administration for alfaxalone required two injections. Two cats receiving 2 mg/kg of alfaxalone for AB did not become recumbent and several cats required additional sedation. High doses of alfaxalone (5 mg/kg) in AB produced superior sedation than 2 mg/kg in AB, but also prolonged recovery. Some cats required oxygen supplementation Peak sedation between 30 mins and 45 mins after SC administration of AB, but enough for the administration of radioiodine in hyperthyroid cats. Tremors and increased sensitivity to noise were observed |

24, 44–47 |

|

Dexmedetomidine + butorphanol

(DBUT) or buprenorphine (DBUP) |

10 Mg/kg + 0.4 mg/kg (DBUT) or 0.02 mg/kg (DBUP) IM; imaging, blood sampling, wound care and chemotherapy or 40 Mg/kg + 0.01 mg/kg (DBUP) IM; echocardiography |

Higher sedation scores with DBUT than DBUP Maximal sedation achieved in 10 mins High prevalence of post-administration vomiting with DBUP Some cats required additional administration of alfaxalone (1.5 mg/kg IM) for venous catheterization DBUP produced chemical restraint (with no need for physical restraint) for echocardiography using high doses of dexmedetomidine (Johard et al 2018). 49 Ventricular and atrial diameters and BP increased; flow velocities, fractional shortening and HR decreased, which could confound diagnosis of cardiomyopathy Vomiting after oral and IM administration was observed in 4/6 and 3/6 cats, respectively. Hypersalivation may also be seen following oral administration, which could impair drug absorption |

48,49 |

| Ketamine + midazolam | 14 mg/kg + 0.5 mg/kg intranasal or M; no endpoint | Similar levels of sedation when both routes of administration were compared In the intranasal group, cats reacted with snorting and/or sneezing. In the IM group, excessive vocalization and changes in behavior suggested pain at injection The nasal mucosa has great vascularization and high permeability that may contribute to rapid drug absorption The authors commonly use a lower dose of ketamine (ie, 5–10 mg/kg) when administered IM |

50 |

| Medetomidine alone ± buprenorphine | 30 mg/kg of medetomidine alone, or 10, 30 or 50 Mg/kg with 0.02 mg/kg of buprenorphine IM; premedication before ovariohysterectomy | Medetomidine (30 Mg/kg) + buprenorphine (0.02 mg/kg) produced a significant isoflurane-sparing effect when compared with medetomidine alone Different doses of medetomidine (10, 30 or 50 Mg/kg) with buprenorphine provided better anesthetic recoveries when compared with medetomidine alone |

32 |

|

Ketamine +

dexmedetomidine (KD) |

3 mg/kg + 5 Mg/kg IM; echocardiography | Similar sedation scores to midazolam (0.4 mg/kg) + butorphanol (0.4 mg/kg) with ketamine (3 mg/kg) (MBK) or dexmedetomidine (5 Mg/kg) (MBD) IM KD produced significantly shorter times to sternal recumbency and standing than MBD, but not MBK. However, atipamezole was not administered to cats after MBD Quality of recovery was superior with KD compared with MBK Vomiting was observed in 4/6 cats with KD Significant changes in hemodynamic parameters were observed after KD and MBD (see text) |

23 |

|

Xylazine

or

dexmedetomidine with ketamine (XK or DK, respectively) |

1 mg/kg or 5 Mg/kg with 3 mg/kg IM; short left eye electroretinography | Yohimbine (0.5 mg/kg) or atipamezole (25 Mg/kg) were administered IM for reversal 30 mins after XK or DK injection Similar onset of action between treatments but cats in the XK group required longer to elevate the head and achieve standing position The protocol was effective for short sedation used for electroretinography |

51 |

Additional PSA protocols are described within the text

IM = intramuscular; HR = heart rate; RR = respiratory rate; BP = blood pressure; SpO2 = saturation of peripheral oxygen; IV = intravenous; SC = subcutaneous

Note: Some PSA protocols may significantly impact diagnostic testing (eg, echocardiography and blood work analysis; Table 5) and this should be considered when interpreting the results

Table 5.

Effects of procedural sedation and analgesia protocols on diagnostic tests

| Diagnostic test | Drug combinations | Effects on diagnostic tests | Comments | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hematology | Propofol-ketamine-dexmedetomidine | Decreased: - Red blood cells - Packed cell volume - Hemoglobin concentration - Mean cell volume - Plasma total protein |

Due to pooling of circulating blood cells in the spleen or other vascular reservoirs owing to decreased sympathetic activity | 23, 52, 53 |

| Acepromazine | Decreased: - Packed cell volume |

53 | ||

| Biochemistry | Ketamine-dexmedetomidine | Decreased: - Lactate concentrations Increased: - Plasma glucose concentrations |

Xylazine and medetomidine result in dose-dependent increases in glucose via inhibition of insulin secretion by agonists of α2-adrenoreceptors. Caution with the use of α2-adrenoreceptor agonists in diabetic cats | 3, 54 |

| Echocardiography and radiography | Dexmedetomidine combinations | Increased: - Cardiac silhouette size - Vertebral heart score - End-diastolic volume - End-systolic volume Decreased: - Ejection fraction - Fractional shortening |

Presumed to be due to increased systemic vascular resistance and afterload. Interpret with caution depending on drug protocol | 23,49,55 |

The following section provides additional information on protocols commonly used for PSA in cats using an evidence-based approach. Detailed pharmacology of these drugs is not presented herein. Drug combinations for PSA are also routinely used for premedication, with important anestheticsparing effects.

Drug protocols for feline PSA: an evidence-based approach

The sedative, cardiorespiratory and metabolic effects of, as well as quality of recovery for, several drug combinations for feline PSA have been reported (see Table 4 for an overview). These drug combinations, together with some additional PSA protocols, are discussed in the text below.

It is important to bear in mind that comparisons are difficult between these studies. A scoring system for feline sedation assessment has not been validated. Most studies have evaluated sedation using interactive visual analog and simple descriptive scales that are dependent on the observer’s experience, leading to large inter-study variability. 56 Various multidimensional scales for sedation scores have also been used but with little validation.24,44,57 Different doses, drug combinations and routes of administration have been reported using either clinical or experimental populations. Protocols have been reported for a single procedure (ie, echocardiography) or for premedication, which cannot be generalized to other situations.

Acepromazine combinations

Acepromazine blocks dopaminergic receptors and decreases reaction to external stimuli. The drug has been used in combination with butorphanol, buprenorphine or methadone as premedication in clinical trials.58–61 Sedation was not always systematically evaluated. These combinations produce a mild calming effect with third eyelid protrusion, purring and kneading, or a state of tranquilization for 2-3 h.58,60–62 Moderate sedation following ace-promazine administration was also effective in lowering propofol dosing requirements for anesthetic induction in cats. 59

In some studies, a eutectic mixture of lidocaine-prilocaine cream was applied over the cephalic vein, and protected with occlusive dressing, after premedication with acepromazine-buprenorphine and approximately 20–30 mins before IV catheterization. This technique avoids excessive physical restraint and behavioral responses to manipulation, especially in cats responding poorly to the sedation.18,60,61 Indeed, the application of this local anesthetic cream reduced the reaction of cats to IV catheterization, as assessed by a numerical rating scale. 63 Even so, acepromazine-opioid combinations will usually produce mild sedation and experienced support staff or veterinarians are often needed for physical restraint and handling. 64

Acepromazine should not be used for PSA in cats with hypovolemia or dehydration, or in procedures with high risk of bleeding (Table 2). Hypothermia and hypotension may occur due to blockade of α1-adrenergic receptors, especially in cats undergoing general anesthesia. Acepromazine combinations should be used with caution in hypovolemic and in hypotensive patients. Acepromazine has some antihistaminic effects and should not be administered to patients undergoing intradermal skin testing.

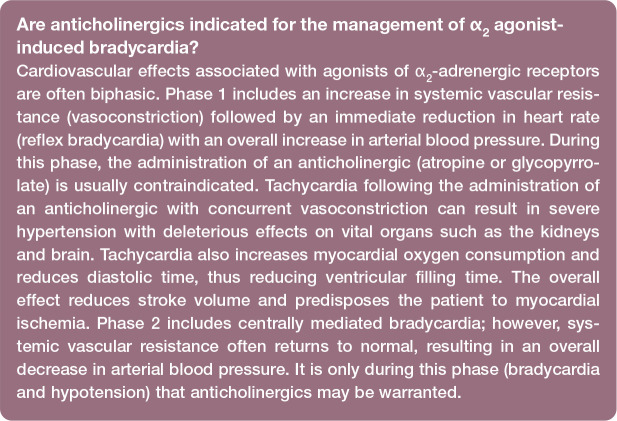

Agonists of α2-adrenergic receptor combinations

Agonists of α2-adrenergic receptors provide sedation, muscle relaxation, analgesia and chemical restraint in a dose-dependent man-ner. 65 They can produce emesis, especially when administered alone, due to direct stimulation of the chemoreceptor trigger zone (more commonly after xylazine). 33 Vomiting becomes an issue in cats with increased intraocular and intracranial pressures, with a detrimental impact on patient health and welfare. These drugs cause peripheral vaso-constriction, hypertension with reflex brady-cardia and decreases in cardiac output. For this reason, agonists of α2-adrenergic receptors are mostly reserved for cats with stable hemodynamic function. Hypothermia can occur via depression of the hypothalamic thermoregulatory center and the lack of muscle activity during PSA.

Dexmedetomidine and medeto-midine are selective agonists of α2-adrenergic receptors and should be preferred over xylazine. Xylazine should not be administered to systemically ill, pediatric or senior cats. Dexmedetomidine is the active isomer of medeto-midine and twice as potent. Dexmedetomidine-butorphanol is a popular drug combination for PSA with a short onset of action (approximately 5 mins). 46 This combination provides superior sedative effects and a lower prevalence of vomiting than dexmedetomidine-buprenorphine during PSA for diagnostic imaging (ultrasound examination, radiography, CT), blood sampling, minor wound care and chemotherapy treatment administration. 48 However, studies have shown that the analgesia produced by dexmedetomidine-buprenorphine is superior.66,67 The thermal antinociceptive effects of dexmedetomidine were enhanced when the drug was combined with buprenorphine. 68 The addition of ketamine (3 mg/kg) to dexmedetomidine (5 ug/kg) and butorphanol (0.3 mg/kg) increased the median duration of action for blood sampling by approximately two-fold. However, sedation scores were not different when compared with dexmedetomidine–butorphanol alone. 69

Dexmedetomidine combinations usually decrease ejection fraction and fractional shortening, and increase end-diastolic and end-systolic volume in cats. This may affect the interpretation of echocardiography results. These combinations (eg, midazolam-butorphanol-dexmedetomidine or ketamine-dexmedetomidine) decrease cardiac output (approximately 50%), significantly more so than ketamine-midazolam-butorphanol (34%). 23 In contrast, medetomidine alone has been shown to increase afterload and was able to attenuate signs of dynamic left ventricular outflow tract obstruction in cats. 70 This is the reason why some veterinarians use low-dose medetomidine combinations for sedation in cats with HCM. Cardiac output is predominantly maintained via heart rate rather than contractility in the pediatric patient (cats <4 months of age). Administration of any α2 receptor agonist in pediatric cats can severely reduce cardiac output and tissue perfusion and requires caution. Similarly, these drugs should not be administered to patients with life-threatening brady-arrythmias (eg, bradycardia secondary to urinary obstruction).

The oral transmucosal (buccal) route of administration has been used with medetomidine or dexmedetomidine as an alternative to intramuscular (IM) injections in cats.57,71 The drug is injected with a 1 ml syringe into the cheek pouch to avoid oral administration (ie, drug swallowing) (Figure 5). Dexmedetomidine (40 jg/kg) in combination with buprenorphine (0.02 mg/kg) produced chemical restraint in cats when drugs were administered either buccally or IM. Sedative effects were not different between the groups. However, IM dosing produced superior sedation compared with buccal dosing when lower doses of dexmedetomidine (20 ug/kg) were used with buprenorphine. 57 Antagonists of α2-adrenergic receptors (atipamezole for dexmedetomidine and medetomidine; yohimbine for xylazine) can be administered IM to hasten recovery and antagonize potential adverse effects. Analgesia and muscle relaxation will also be antagonized. Atipamezole is typically administered IM at equal dose volume as the dexmedetomidine (0.5 mg/ml) or medetomi-dine volume. When using dexmedetomidine at 0.1 mg/ml concentration, the volume of atipamezole should be reduced to one-fifth of the dexmedetomidine dose volume. To reverse xylazine, administer 0.025–0.05 mg/kg of yohimbine IV slowly (25% of the published total dose), with the remaining 75% of the dose administered IM. This technique can help minimize yohimbine’s unwanted side effects (ie, excitement and hypotension). Note that the use of anticholinergics with agonists of α2-adrenergic receptors is normally contraindicated (see box).

Figure 5.

Oral transmucosal (buccal) administration of dexmedetomidine and buprenorphine can provide 'hands-off' sedation, analgesia and chemical restraint. Palatability is generally acceptable. Drug absorption is by the transmucosal route, assuming the drug is not spilled or swallowed by the cat

Benzodiazepine combinations

The administration of benzodiazepines inconsistently produces sedation, and more commonly results in a transient period of excitement in adult, healthy cats. Patients may actually show signs of paradoxical aggressive and defensive behaviors.23,72 There is generally a clinical impression that benzo-diazepines cause minimal cardiovascular depression, but in one early study doses of 0.1 mg/kg of diazepam reduced systolic blood pressure and cardiac contractility, potentially because of the presence of propylene glycol in the formulation. 73 Nevertheless, midazolam and diazepam may be used for coinduction after the administration of propofol for endotracheal intubation in systemically ill cats. Benzodiazepines enhance the affinity of the neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABAA) for its receptor and have a synergistic effect with barbiturates, propofol and alfaxalone. Doses as low as 0.2 and 0.3 mg/kg of midazolam and diazepam, respectively, may have a propofol-sparing effect. 59

In the authors’ experience, midazolam-opioid combinations can be used in senior or critically ill cats (see top-right box on page 1035) to produce sedation for minor diagnostic procedures. Benzodiazepines are also used in combination with ketamine (see below). Diazepam should not be administered IM because the drug is hydrophobic and contains propylene glycol, which causes pain at injection; midazolam is water soluble and recommended for injectable PSA protocols. Flumazenil (0.01–0.04 mg/kg) is the antagonist of benzodiazepines.

Ketamine-based combinations

Ketamine, an N-methyl D-aspartate (NMDA) antagonist, causes dissociation between the thalamoneocortical and limbic systems. 74 It is used as an adjunct analgesic in patients with hyperalgesia or central sensitization, 75 and can be administered IV, IM or buccally in cats.76–78 In humans, ketamine used at subanesthetic doses (<1 mg/kg) rapidly decreased the perception of severe, acute pain and provided an opioid-sparing effect.79,80 Its ability to produce similar analgesic effects at low doses is yet to be determined in cats. 81 This drug is known for causing ‘emergence phenomenon’ (dysphoria during recovery) in a variety of species, including humans, although it is not routinely seen with subanesthetic doses in cats (<0.5 mg/kg). 81 Ketamine is always administered in combination with sedatives and analgesics. The swallowing reflex is well maintained, but the risk of aspiration is still present. 82

Ketamine-based protocols are used to produce chemical restraint for PSA (Table 4). The drug must be combined with a muscle relaxant (ie, midazolam or an agonist of α2-adrenergic receptors) to prevent muscle rigidity, seizure activity and hypersalivation. The drug has an acidic pH and may cause pain during IM injection. 50 For this reason, appropriate physical restraint is required for the administration of ketamine combinations. Ketamine has the potential to increase heart rate via increases in sympathetic tone and should be avoided in patients with HCM or tachy arrhythmias.

Tiletamine-zolazepam and combinations

Tiletamine-zolazepam is available as a white powder combination (500 mg combined) and is reconstituted with 5 ml of sterile water to produce a 100 mg/ml solution. Alternatively, tiletamine-zolazepam powder can be reconstituted with 100 mg of xylazine and 400 mg of ketamine and administered IM at 3.3 mg/kg to cats for anesthesia. Following reconstitution, any unused drug should be discarded after 7 days when stored at room temperature or after 56 days when refrigerated.

This drug combination is widely used in feline practice for PSA and surgery. Sympathetic stimulation is observed after drug administration due to central nervous system stimulation, depression of baroreceptors and inhibition of norepinephrine (noradrenaline) uptake at adrenergic nerve endings. 83 Tiletamine-zolazepam can produce muscle rigidity, myoclonus, salivation, respiratory depression and prolonged recovery from anesthesia, which is a potential concern for patient welfare. 84 The combination of low doses of tiletamine-zolazepam with methadone provided superior sedation to acepromazine-methadone in healthy cats before neutering (Table 4). 37 Similar to ketamine combinations, tiletamine-zolazepam combinations should be avoided in cats with HCM.

Alfaxalone and combinations

Alfaxalone is a synthetic neurosteroid anesthetic drug that has been studied for PSA in cats.24,41,42 The sedative and cardiores-piratory effects of alfaxalone have been evaluated when the drug was administered alone or in combination with butorphanol, hydromorphone or dexmedetomidine (Table 4). These protocols are versatile with a wide margin of safety and used for various procedures in combination with opioids (Table 4). Hypoventilation is a potential adverse effect of alfaxalone use in cats. 85 Some studies have reported ataxia, excitement and hyper-reactivity in some individuals during the recovery phase when doses of 5 mg/kg were used; 43 these effects may be attenuated by the administration of acepromazine and butorphanol. 86

Alfaxalone-based protocols may involve large-volume IM injections. For example, a dose of 5–10 mg/kg may require 2–5 ml of volume administration. Cats may react to the injection even after sedation with dexmedeto-midine-butorphanol. 43 The high volume produces discomfort and violent reactions at injection when administered at 10 mg/kg. 43 Other studies have reported that IM injections are normally tolerated when low doses are used (2 mg/kg). 46 The quality of anesthetic recovery is also a concern with alfaxalone. 87 Studies have reported cats thrashing, paddling, trembling and pacing in the cage.43,87 Jurox, the manufacturer of Alfaxan Multidose, reports that repeated, supraclinical doses (25 mg/kg) of the product administered IV q48h for three doses does not result in adverse effects in cats. 88

Propofol

The phenolic compound propofol is used as an anesthetic induction agent and, in some cases, for maintenance of anesthesia (total IV anesthesia). Propofol is sometimes administered as small boluses for PSA but it can induce adverse effects, especially in systemically ill cats. The drug produces dose-dependent cardiorespiratory depression with variable changes in heart rate, decreases in cardiac contractility and respiratory rate, hypoxia, hypercapnia and vasodilation.52,89–93 Although hypotension may be observed following propofol administration, it is often mild in healthy cats. 92 Apnea may occur, especially after rapid bolus administration.89,94–96 Caution is required when using propofol for PSA in patients with respiratory compromise and oxygen supplementation should be provided.

Small doses of propofol (1 mg/kg) may induce light sedation with signs of excitement and increased muscular activity in healthy cats (ASA PS I or II) sedated with acepro-mazine-methadone. 59 In contrast, these doses have been shown to induce smooth and mild sedation in critically ill cats with urinary obstruction requiring PSA for urethral catheterization after sedation with a midazolam-opioid combination. 97 Indeed, benzodiazepines may reduce propofol requirements for endotracheal intubation by 35% in healthy cats sedated with acepromazine-methadone 59 and by 26% in unpremedicated cats. 98

The development of Heinz bodies after a 30-min infusion of propofol has been reported in cats, but only following the third day of administration; 99 after 7 consecutive days of these 30-min infusions, hemolysis was not detected. 99 The concern for Heinz body development associated with propofol administration in cats is, as yet, undetermined, as it does not appear to have clinical significance even following 24-h propofol infusions. 93

PropoFlo 28 (Zoetis) contains 20 mg/ml of benzyl alcohol, a bacteriostatic preservative that requires glucuronidation for metabolism, and is a multiuse formulation of propofol with a 28-day shelf life. Excessive quantities of benzyl alcohol (>156 mg in 6.5 h) may cause central nervous system toxicity and potentially death. 100 For a standard 3 kg cat, an extreme overdose of propofol (approximately 26 mg/kg) would be required to produce these adverse effects.

Monitoring during PSA

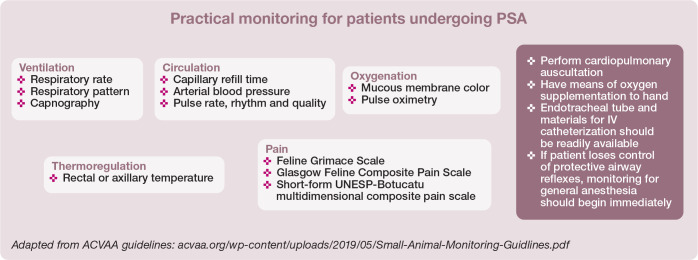

Appropriate monitoring prevents, detects and aids in the treatment of complications such as hypoxia, hypoventilation and apnea, hypothermia, bronchospasm, cardiovascular depression, post-sedation delirium, prolonged recovery, vomiting and aspiration.4,9,101 The American College of Veterinary Anesthesiology and Analgesia (ACVAA) has published guidelines for monitoring of patients undergoing sedation (see box).

Routine neurological assessment (menace response, nystagmus, palpebral reflex, response to stimuli) monitors the depth of sedation.

Pulse oximetry (SpO2) is a valuable monitoring tool during the sedation and recovery periods. Transmission SpO2 probes placed on the tongue, pinna or a (non-pigmented) toe can provide an early indication of respiratory complications and can significantly reduce the risk of mortality (Figure 6). 3 Failure to monitor oxygen saturation during sedation and anesthesia also increased the risk of death. 2 In patients receiving high levels of fractional inspired oxygen (FiO2), pulse oximetry can be misleading because desaturation may not be apparent until a patient is truly hypoxemic. Note also that pulse oximetry values may be affected by or unattainable with the administration of α2-adrenergic agonists (eg, dexmedetomidine or medetomidine).

Capnography is often not employed because patients are not routinely intubated during PSA. However, a side stream adapter can be placed close to the patient’s nostrils to estimate end-tidal carbon dioxide values and monitor ventilation (Figure 6).

Non-invasive blood pressure monitoring using techniques such as oscillometry or Doppler ultrasound and sphygmomanometry is a cost-effective and simple method for indirect assessment of perfusion. The Doppler provides an audio, real-time pulse for rate and rhythm evaluation. Obesity may impact Doppler probe blood pressure readings from the coccygeal and radial artery. 102 There is potential for Doppler measurements to more closely resemble mean arterial pressure in cats. 103 Regardless, blood pressure trends associated with heart rate and oxygenation are the most important outcome for monitoring when using these devices.

Figure 6.

Capnography (performed using a side-stream adapter), pulse oximetry and cardiac auscultation in a cat undergoing procedural sedation and analgesia for an abdominal ultrasound examination. Courtesy of Mary T Schacher

Recovery procedures

The quality of recovery is dependent on body temperature, duration of the procedure, drug antagonism (whether performed and/or effective), pain, and patient health status and behavior. Complications may arise during the sedation period; however, the majority of fatalities (52–60%) have been reported to occur within the first 3 h after the procedure has ended.2,5

Prolonged hypothermia and emergence, collapse and/or excitement may occur during recovery. 9 This is particularly true when anesthetics are administered for PSA. Post-procedure excitement or delirium can be controlled with dexmedetomidine (0.5–1 jg/kg IV) administered slowly for re-sedation in a quiet environment away from other animals. Management and prevention of hypothermia during PSA was discussed earlier (see section on ‘patient assessment preparation before PSA’) and the same principles apply during recovery. Reversal agents for opioids, benzodiazepines and α2-adrenergic agonists should be readily available and administered in the event of prolonged emergence from PSA. Hypotension has been reported following the reversal of dexmedetomidine with atipamezole in isoflurane-anesthetized cats; 104 however, this should not be a concern during PSA. Monitoring should continue for a minimum of 3 h following completion of the procedure and animals should not be left unattended for long periods of time until they have recovered.

Patients are considered fully recovered when they are responsive to normal stimuli, have regained protective airway reflexes and are able to maintain normal cardiopulmonary parameters. Some cats may require continuous monitoring and oxygenation (eg, oxygen tent or chamber). If intubation was necessary, extubation is recommended when a convincing swallowing reflex is present; cats should be monitored for laryngospasm and upper airway obstructions following extubation. A small amount of water and food can be offered to patients that are awake and standing with minimal to no ataxia.

Key Points

Feline patients often require PSA in veterinary practice for various procedures.

Complications may arise, especially when risk factors are present.

The choice of drug protocol depends on the procedure and the health status of the patient, including any concomitant diseases.

The need for analgesia dictates the type of opioid to be administered.

The results of clinical and experimental trials are difficult to extrapolate to every case, and an individualized approach to PSA should be taken. 1

Monitoring, fluid therapy and good practices, as discussed in this article, are paramount for successful PSA in cats.

Footnotes

Dr Paulo Steagall has provided consultancy services to Boehringer Ingelheim, Dechra Pharmaceuticals, Elanco, Procyon and Zoetis; has acted as a key opinion leader to Boehringer Ingelheim, Dechra Pharmaceuticals, Elanco, Vetoquinol and Zoetis; and has received speaker honoraria from Boehringer Ingelheim, Dechra Pharmaceuticals, Elanco and Zoetis.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval: This work did not involve the use of animals and therefore ethical approval was not necessarily required.

Informed consent: This work did not involve the use of animals and therefore informed consent was not required. For any animals or humans individually identifiable within this publication, informed consent (either verbal or written) for their use in the publication was obtained from the people involved.

Contributor Information

Bradley T Simon, Department of Small Animal Clinical Sciences, College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, USA.

Paulo V Steagall, Department of Clinical Sciences, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Universite de Montreal, Saint-Hyacinthe, Canada.

References

- 1. Godwin SA, Burton JH, Gerardo CJ, et al. Clinical policy: procedural sedation and analgesia in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med 2014; 63: 247-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Matthews NS, Mohn TJ, Yang M, et al. Factors associated with anesthetic-related death in dogs and cats in primary care veterinary hospitals. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2017; 250: 655-665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brodbelt DC, Pfeiffer DU, Young LE, et al. Risk factors for anaesthetic-related death in cats: results from the confidential enquiry into perioperative small animal fatalities (CEPSAF). Br J Anaesth 2007; 99: 617-623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brodbelt D. Feline anesthetic deaths in veterinary practice. Top Companion Anim Med 2010; 25: 189-194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brodbelt DC, Pfeiffer DU, Young LE, et al. Results of the confidential enquiry into perioperative small animal fatalities regarding risk factors for anesthetic-related death in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2008; 233: 1096-1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bille C, Auvigne V, Libermann S, et al. Risk of anaesthetic mortality in dogs and cats: an observational cohort study of 3546 cases. Vet Anaesth Analg 2012; 39: 59-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Levy JK, Bard KM, Tucker SJ, et al. Perioperative mortality in cats and dogs undergoing spay or castration at a high-volume clinic. Vet J 2017; 224: 11-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Baetge CL, Matthews NS. Anesthesia and analgesia for geriatric veterinary patients. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2012; 42: 643-653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dyson DH, Maxie MG, Schnurr D. Morbidity and mortality associated with anesthetic management in small animal veterinary practice in Ontario. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 1998; 34: 325-335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gruenheid M, Aarnes TK, McLoughlin MA, et al. Risk of anesthesia-related complications in brachycephalic dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2018; 253: 301-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lindsay B, Cook D, Wetzel JM, et al. Brachycephalic airway syndrome: management of post-operative respiratory complications in 248 dogs. Aust Vet J 2020; 98: 173-180. DOI: 10.1111/avj.12926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Davis H, Jensen T, Johnson A, et al. 2013 AAHA/AAFP fluid therapy guidelines for dogs and cats. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2013; 49: 149-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. van Haaften KA, Forsythe LRE, Stelow EA, et al. Effects of a single preappointment dose of gabapentin on signs of stress in cats during transportation and veterinary examination. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2017; 251: 1175-1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pankratz KE, Ferris KK, Griffith EH, et al. Use of single-dose oral gabapentin to attenuate fear responses in cage-trap confined community cats: a double-blind, placebo-controlled field trial. J Feline Med Surg 2018; 20: 535-543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pypendop BH, Siao KT, Ilkiw JE. Thermal antinociceptive effect of orally administered gabapentin in healthy cats. Am J Vet Res 2010; 71: 1027-1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Stevens BJ, Frantz EM, Orlando JM, et al. Efficacy of a single dose of trazodone hydrochloride given to cats prior to veterinary visits to reduce signs of transport- and examination-related anxiety. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2016; 249: 202-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Orlando JM, Case BC, Thomson AE, et al. Use of oral trazodone for sedation in cats: a pilot study. J Feline Med Surg 2016; 18: 476-482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Simon BT, Steagall PV, Monteiro BP, et al. Antinociceptive effects of intravenous administration of hydromorphone hydrochlo-ride alone or followed by buprenorphine hydrochloride or butorphanol tartrate to healthy conscious cats. Am J Vet Res 2016; 77: 245-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Simon BT, Scallan EM, Baetge CL, et al. The antinociceptive effects of intravenous administration of three doses of butor-phanol tartrate or naloxone hydrochloride following hydromor-phone hydrochloride to healthy conscious cats. Vet Anaesth Analg 2019; 46: 538-547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Robertson SA, Gogolski SM, Pascoe P, et al. AAFP feline anesthesia guidelines. J Feline Med Surg 2018; 20: 602-634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Grubb T, Sager J, Gaynor JS, et al. 2020 AAHA anesthesia and monitoring guidelines for dogs and cats. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2020; 56: 59-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Auger M, Fazio C, de Swarte M, et al. Administration of certain sedative drugs is associated with variation in sonographic and radiographic splenic size in healthy cats. Vet Radiol Ultrasound 2019; 60: 717-728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Biermann K, Hungerbuhler S, Mischke R, et al. Sedative, cardiovascular, haematologic and biochemical effects of four different drug combinations administered intramuscularly in cats. Vet Anaesth Analg 2012; 39: 137-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Deutsch J, Jolliffe C, Archer E, et al. Intramuscular injection of alfaxalone in combination with butorphanol for sedation in cats. Vet Anaesth Analg 2017; 44: 794-802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Thomassen O, Faerevik H, Osteras O, et al. Comparison of three different prehospital wrapping methods for preventing hypothermia – a crossover study in humans. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2011; 19: 41. DOI: 10.1186/1757-7241-19-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bissonnette B, Swan H, Ravussin P, et al. Neuroleptanesthesia: current status. Can J Anesth 1999; 46: 154-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Steagall PV. Sedation and premedication. In: Steagall P, Taylor P. (eds). Feline anesthesia and pain management. Hoboken, NJ, USA: Wiley Blackwell, 2018, pp 35-48. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Doi M, Ikeda K. Airway irritation produced by volatile anaesthetics during brief inhalation: comparison of halothane, enflurane, isoflurane and sevoflurane. Can J Anesth 1993; 40: 122-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Schmid RD, Hodgson DS, McMurphy RM. Comparison of anesthetic induction in cats by use of isoflurane in an anesthetic chamber with a conventional vapor or liquid injection technique. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2008; 233: 262-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Deng HB, Li FX, Cai YH, et al. Waste anesthetic gas exposure and strategies for solution. J Anesth 2018; 32: 269-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Selmi AL, Mendes GM, Lins BT, et al. Evaluation of the sedative and cardiorespiratory effects of dexmedetomidine, dexmedeto-midine-butorphanol, and dexmedetomidine-ketamine in cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2003; 222: 37-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Grint NJ, Burford J, Dugdale AH. Investigating medetomi-dine-buprenorphine as preanaesthetic medication in cats. J Small Anim Pract 2009; 50: 73-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nagore L, Soler C, Gil L, et al. Sedative effects of dexmedetomi-dine, dexmedetomidine-pethidine and dexmedetomidine–butorphanol in cats. J Vet Pharmacol Ther 2013; 36: 222-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Simon BT, Steagall PV. The present and future of opioid analgesics in small animal practice. J Vet Pharmacol Ther 2017; 40: 315-326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bortolami E, Love EJ. Practical use of opioids in cats: a state-of-the-art, evidence-based review. J Feline Med Surg 2015; 17: 283-311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Steagall PV, Monteiro-Steagall BP, Taylor PM. A review of the studies using buprenorphine in cats. J Vet Intern Med 2014; 28: 762-770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mair A, Kloeppel H, Ticehurst K. A comparison of low dose tiletamine-zolazepam or acepromazine combined with methadone for pre-anaesthetic medication in cats. Vet Anaesth Analg 2014; 41: 630-635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Nejamkin P, Cavilla V, Clausse M, et al. Sedative and physiologic effects of tiletamine-zolazepam following buccal administration in cats. J Feline Med Surg 2020; 22: 108-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cistola AM, Golder FJ, Centonze LA, et al. Anesthetic and physiologic effects of tiletamine, zolazepam, ketamine, and xylazine combination (TKX) in feral cats undergoing surgical sterilization. J Feline Med Surg 2004; 6: 297-303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ward JL, Schober KE, Fuentes VL, et al. Effects of sedation on echocardiographic variables of left atrial and left ventricular function in healthy cats. J Feline Med Surg 2012; 14: 678-685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rodrigo-Mocholi D, Belda E, Bosmans T, et al. Clinical efficacy and cardiorespiratory effects of intramuscular administration of alfaxalone alone or in combination with dexmedeto-midine in cats. Vet Anaesth Analg 2016; 43: 291-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tamura J, Ishizuka T, Fukui S, et al. Sedative effects of intramuscular alfaxalone administered to cats. J Vet Med Sci 2015; 77: 897-904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Grubb TL, Greene SA, Perez TE. Cardiovascular and respiratory effects, and quality of anesthesia produced by alfax-alone administered intramuscularly to cats sedated with dexmedetomidine and hydromorphone. J Feline Med Surg 2013; 15: 858-865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ribas T, Bublot I, Junot S, et al. Effects of intramuscular sedation with alfaxalone and butorphanol on echocardiographic measurements in healthy cats. J Feline Med Surg 2015; 17: 530-536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Granfone MC, Walker JM, Smith LJ. Evaluation of an intramuscular butorphanol and alfaxalone protocol for feline blood donation: a pilot study. J Feline Med Surg 2018; 20: 793-798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Reader RC, Barton BA, Abelson AL. Comparison of two intramuscular sedation protocols on sedation, recovery and ease of venipuncture for cats undergoing blood donation. J Feline Med Surg 2019; 21: 95-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ramoo S, Bradbury LA, Anderson GA, et al. Sedation of hyper-thyroid cats with subcutaneous administration of a combination of alfaxalone and butorphanol. Aust Vet J 2013; 91: 131-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bhalla RJ, Trimble TA, Leece EA, et al. Comparison of intramuscular butorphanol and buprenorphine combined with dexmedetomidine for sedation in cats. J Feline Med Surg 2018; 20: 325-331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Johard E, Tidholm A, Ljungvall I, et al. Effects of sedation with dexmedetomidine and buprenorphine on echocardiographic variables, blood pressure and heart rate in healthy cats. J Feline Med Surg 2018; 20: 554-562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Marjani M, Akbarinejad V, Bagheri M. Comparison of intranasal and intramuscular ketamine-midazolam combination in cats. Vet Anaesth Analg 2015; 42: 178-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Del Sole MJ, Nejamkin P, Cavilla V, et al. Comparison of two sedation protocols for short electroretinography in cats. J Feline Med Surg 2018; 20: 172-178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Griffenhagen GM, Rezende ML, Gustafson DL, et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of propofol with or without 2% benzyl alcohol following a single induction dose administered intravenously in cats. Vet Anaesth Analg 2015; 42: 472-483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Sutil DV, Mattoso CRS, Volpato J, et al. Hematological and splenic Doppler ultrasonographic changes in dogs sedated with acepromazine or xylazine. Vet Anaesth Analg 2017; 44: 746-754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kanda T, Hikasa Y. Neurohormonal and metabolic effects of medetomidine compared with xylazine in healthy cats. Can J Vet Res 2008; 72: 278-286. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Zwicker LA, Matthews AR, Cote E, et al. The effect of dexmedetomidine on radiographic cardiac silhouette size in healthy cats. Vet Radiol Ultrasound 2016; 57: 230-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Benito J, Monteiro BP, Beauchamp G, et al. Evaluation of inter-observer agreement for postoperative pain and sedation assessment in cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2017; 251: 544-551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Santos LC, Ludders JW, Erb HN, et al. Sedative and cardio-respiratory effects of dexmedetomidine and buprenorphine administered to cats via oral transmucosal or intramuscular routes. Vet Anaesth Analg 2010; 37: 417-424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Steagall PV, Aucoin M, Monteiro BP, et al. Clinical effects of a constant rate infusion of remifentanil, alone or in combination with ketamine, in cats anesthetized with isoflurane. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2015; 246: 976-981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Robinson R, Borer-Weir K. The effects of diazepam or mida-zolam on the dose of propofol required to induce anaesthesia in cats. Vet Anaesth Analg 2015; 42: 493-501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Benito J, Evangelista MC, Doodnaught GM, et al. Analgesic efficacy of bupivacaine or bupivacaine-dexmedetomidine after intraperi-toneal administration in cats: a randomized, blinded, clinical trial. Front Vet Sci 2019; 6: 307. DOI: 10.3389/fvets.2019.00307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Benito J, Monteiro B, Lavoie AM, et al. Analgesic efficacy of intraperitoneal administration of bupivacaine in cats. J Feline Med Surg 2016; 18: 906-912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Steagall PV, Taylor PM, Brondani JT, et al. Antinociceptive effects of tramadol and acepromazine in cats. J Feline Med Surg 2008; 10: 24-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Oliveira RL, Soares JH, Moreira CM, et al. The effects of lido-caine-prilocaine cream on responses to intravenous catheter placement in cats sedated with dexmedetomidine and either methadone or nalbuphine. Vet Anaesth Analg 2019; 46: 492-495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Bortolami E, Murrell JC, Slingsby LS. Methadone in combination with acepromazine as premedication prior to neutering in the cat. Vet Anaesth Analg 2013; 40: 181-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Ansah OB, Raekallio M, Vainio O. Comparison of three doses of dexmedetomidine with medetomidine in cats following intramuscular administration. J Vet Pharmacol Ther 1998; 21: 380-387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Taylor PM, Kirby JJ, Robinson C, et al. A prospective multi-centre clinical trial to compare buprenorphine and butorphanol for postoperative analgesia in cats. J Feline Med Surg 2010; 12: 247-255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Warne LN, Beths T, Holm M, et al. Evaluation of the peri-operative analgesic efficacy of buprenorphine, compared with butorphanol, in cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2014; 245: 195-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Slingsby LS, Murrell JC, Taylor PM. Combination of dexmedetomidine with buprenorphine enhances the anti-nociceptive effect to a thermal stimulus in the cat compared with either agent alone. Vet Anaesth Analg 2010; 37: 162-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Volpato J, Mattoso CR, Beier SL, et al. Sedative, hematologic and hemostatic effects of dexmedetomidine–butorphanol alone or in combination with ketamine in cats. J Feline Med Surg 2015; 17: 500-506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Lamont LA, Bulmer BJ, Sisson DD, et al. Doppler echocardiograph-ic effects of medetomidine on dynamic left ventricular outflow tract obstruction in cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2002; 221: 1276-1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Porters N, Bosmans T, Debille M, et al. Sedative and antinocicep-tive effects of dexmedetomidine and buprenorphine after oral transmucosal or intramuscular administration in cats. Vet Anaesth Analg 2014; 41: 90-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Ilkiw JE, Suter CM, Farver TB, et al. The behaviour of healthy awake cats following intravenous and intramuscular administration of midazolam. J Vet Pharmacol Ther 1996; 19: 205-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Chai CY, Wang SC. Cardiovascular actions of diazepam in the cat. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1966; 154: 271-280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Bahn EL, Holt KR. Procedural sedation and analgesia: a review and new concepts. Emerg Med Clin North Am 2005; 23: 503-517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Goich M, Bascunan A, Faundez P, et al. Multimodal analgesia for treatment of allodynia and hyperalgesia after major trauma in a cat. JFMS Open Rep 2019; 5. DOI: 10.1177/2055116919855809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Wetzel RW, Ramsay EC. Comparison of four regimens for intraoral administration of medication to induce sedation in cats prior to euthanasia. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1998; 213: 243-245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Hanna RM, Borchard RE, Schmidt SL. Pharmacokinetics of ketamine HCl and metabolite I in the cat: a comparison of i.v., i.m., And rectal administration. J Vet Pharmacol Ther 1988; 11: 84-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Grove DM, Ramsay EC. Sedative and physiologic effects of orally administered alpha 2-adrenoceptor agonists and ketamine in cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2000; 216: 1929-1932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Ahern TL, Herring AA, Stone MB, et al. Effective analgesia with low-dose ketamine and reduced dose hydromorphone in ED patients with severe pain. Am J Emerg Med 2013; 31: 847-851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Beaudoin FL, Lin C, Guan W, et al. Low-dose ketamine improves pain relief in patients receiving intravenous opioids for acute pain in the emergency department: results of a randomized, double-blind, clinical trial. Acad Emerg Med 2014; 21: 1193-1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Ambros B, Duke T. Effect of low dose rate ketamine infusions on thermal and mechanical thresholds in conscious cats. Vet Anaesth Analg 2013; 40: e76-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Wilson ML, Ritschel WA. The development of a sedation model in dogs. Methods Find Exp Clin Pharmacol 1990; 12: 251-256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Hellyer P, Muir WW, 3rd, Hubbell JA, et al. Cardiorespiratory effects of the intravenous administration of tiletamine-zolazepam to cats. Vet Surg 1988; 17: 105-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Forsyth S. Administration of a low dose tiletamine-zolazepam combination to cats. N Z Vet J 1995; 43: 101-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Muir W, Lerche P, Wiese A, et al. The cardiorespiratory and anesthetic effects of clinical and supraclinical doses of alfaxalone in cats. Vet Anaesth Analg 2009; 36: 42-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Zaki S, Ticehurst K, Miyaki Y. Clinical evaluation of Alfaxan-CD(R) as an intravenous anaesthetic in young cats. Aust Vet J 2009; 87: 82-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Mathis A, Pinelas R, Brodbelt DC, et al. Comparison of quality of recovery from anaesthesia in cats induced with propo-fol or alfaxalone. Vet Anaesth Analg 2012; 39: 282-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Pasloske K, Whittem T. JX9604.07-H004. A target animal safety study in cats after administration of Alfaxan®-CD RTU as single, repeated injections on days 0, 2, and 5 at dosages of 5, 15 or 25 mg/kg. https://www.jurox.com/au/reference/pasloske-k-and-t-whittem-jx960407-h004-target-animal-safety-study-cats-after (2004, accessed August 18 2020).