Abstract

Case series summary

The aim of this case series is to describe the clinical and radiological features of mandibular and maxillary abnormalities in cats diagnosed with patellar fractures and dental anomalies, a condition that we have named ‘patellar fracture and dental anomaly syndrome’ (PADS), also known previously as ‘knees and teeth syndrome’. Where available, clinical records, skull and/or intraoral dental radiographs, head CT images, microbiology and histopathology reports were collected, and follow-up was obtained. Ten cats with mandibular or maxillary abnormalities were identified. Common clinical features included multiple persistent deciduous teeth, gingivitis and swellings of the jaw. Skull radiographs were available for 7/10 cats and head CT images were available for one cat. Findings included marked bony and periosteal proliferation, hypodontia, root resorption, root malformation and unerupted permanent teeth. Where available, microbiology and histopathology results were consistent with osteomyelitis.

Relevance and novel information

Mandibular and maxillary abnormalities are an additional unreported clinical feature of the rare condition that we have termed PADS. Radiologically, these lesions can have an aggressive appearance, which can mimic neoplasia. Medical management with antibiotic and anti-inflammatory therapy improves clinical signs in the short term; however, surgical extraction of persistent deciduous and unerupted permanent teeth, and debridement of proliferative and necrotic bone appear to be necessary for an improved outcome. Additional information on long-term outcome is required.

Keywords: Patellar fracture, persistent deciduous teeth, osteomyelitis, osteopetrosis

Introduction

Cats with patellar fractures are a fairly rare presentation in veterinary practice. A survey of feline patellar fractures published in 2009 documented findings from 52 patellar fractures in 34 cats. 1 It was revealed that feline patellar fractures most commonly occur spontaneously in young adult cats at a mean age of 28 months. Over 50% of cats subsequently develop fractures of the contralateral patella with a median interval of 3 months from the first patellar fracture. 1 Fractures in these cases were consistently transverse and at the level of the mid to proximal third of the patella. 1 Radiological evidence of increased bone opacity of the fractured patella and contralateral non-fractured patella was demonstrated in the majority of cases, a finding suggestive of a response to repetitive mechanical stimulus and a feature of stress fractures. 2 In addition, cats with atraumatic patellar fractures often sustain fractures of other bones; the proximal tibia, acetabulum, ischium, humeral condyle and calcaneus being the most frequently reported bones affected.3,4 It has therefore been postulated that these cats may be suffering from a primary bone disorder; the nature of which has not yet been identified.

The initial publication by Langley-Hobbs centred investigations on patellar fractures as the presenting complaint; however, analysis of collated data revealed that 5/34 cats with patellar fractures (15%) also had deciduous teeth persisting beyond 6 months of age. 1 Subsequent radiological evaluation has indicated that a number of these cats also have unerupted permanent teeth. The combination of patellar fractures and dental abnormalities has led to the coining of the term ‘patellar fracture and dental anomaly syndrome’ (PADS), also known previously as ‘knees and teeth syndrome’. 5

Furthermore, from author experience, a small number of cats affected by this syndrome develop mandibular and maxillary abnormalities. The aim of this publication is to report the clinical and radiological features of mandibular and maxillary abnormalities in cats with PADS.

Case series description

Cats with a history of mandibular and/or maxillary abnormalities and patellar fractures were recruited from a combined database of two authors (SLH and SB). Cases in the combined database included cats with the following clinical features: transverse patellar fractures with or without dental anomalies (including persistent deciduous teeth and unerupted adult teeth) and one or more atraumatic fractures to other bones. Cases had been collected since 2005.

Of the cases identified, all information submitted to the databases was collated and, where possible, further case follow-up was performed. Where available, records of clinical history, skull and/or intraoral dental radiographs, head CT images, and microbiology and histopathology reports were included. All available radiographs and CT images were reviewed separately by specialists in veterinary diagnostic imaging (AM) and veterinary dentistry (MG), who were provided with a basic knowledge of case clinical presentation and treatments performed. The combined database had a total of 191 cats, 92 of which had recorded dental abnormalities. Ten cats with mandibular and/or maxillary abnormalities were identified. The results are summarised briefly in Table 1, and in more detail on a case-by-case basis.

Table 1.

Summary of signalment and fractures sustained for cases 1–10

| Case | Sex | Breed | Retained teeth | Patellar fracture | Tibial fracture | Pelvic fracture | Humeral fracture | Calcaneal fracture | Femoral fracture | Other fractures |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | MN | DSH | Unknown | XX | XX | XX | X | |||

| 2 | FN | DSH | Yes | XX | X | X | ||||

| 3 | FN | DLH | Yes | X | ||||||

| 4 | FN | Siamese X |

Yes | X | X | |||||

| 5 | MN | DSH | Yes | XX | X | |||||

| 6 | FE | DSH | Yes | XX | X | X | ||||

| 7 | FN | Maine Coon X | Yes | X | ||||||

| 8 | FN | DSH | Yes | XX | X | |||||

| 9 | FN | DSH | Yes | X | Olecranon; rib | |||||

| 10 | FN | DSH | Yes | X | X | X | X |

MN = male neutered; DSH = domestic shorthair; FN = female neutered; DLH = domestic longhair; Siamese X = Siamese cross; FE = female entire; Maine Coon X = Maine Coon cross; X = unilateral fracture; XX = bilateral fractures

Case 1

An adult male neutered domestic shorthair (DSH) cat presented with a history of fractures of the patella, tibia, lateral humeral condyle and ischium, and a maxillary swelling. Radiographs of the skull demonstrated a unilateral, expansile and proliferative bony lesion of the maxilla (Figure 1). The lesion exhibited a region of marked, but smooth and solid periosteal proliferation without significant evidence of radiologically aggressive characteristics. Differential diagnoses based on radiographic appearance included osteoma, osteochondroma and low-grade osteomyelitis, with chondrosarcoma and osteosarcoma considered less likely. No follow-up information was available as this cat was euthanased following the diagnosis of a second patellar fracture.

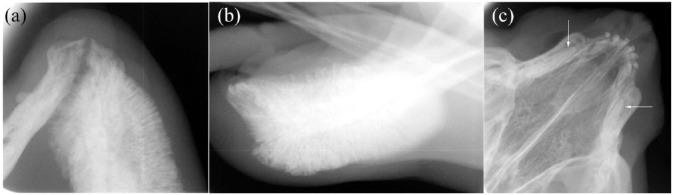

Figure 1.

Dorsoventral skull radiograph from case 1 showing a unilateral expansile and proliferative bony lesion of the maxilla and rostral zygomatic bone with a well-defined zone of transition and no evidence of cortical destruction

Case 2

A female neutered DSH cat presented at 8 months of age with inappetence and a painful swelling of the right rostral mandible, which was most compatible with an abscess of unknown origin. Multiple persistent deciduous teeth were also identified on clinical examination. Purulent material from the mandibular swelling was cultured and Pasteurella species and anaerobes were isolated. A skull radiograph was unremarkable. A clinical improvement was observed following a 2 week course of oral marbofloxacin (2.75 mg/kg PO q24h); the mandibular swelling reduced in size but did not completely resolve.

At 9 months of age the cat presented with right hindlimb lameness and recurrence of the mandibular abscess, and antibiotics were administered (as previously prescribed). At 10 months of age, the cat developed left hindlimb lameness and radiographs revealed bilateral patellar fractures, which were managed conservatively. The cat subsequently sustained a fracture of the right proximal femur followed by a fracture of the left tarsus; both fractures were managed surgically.

Recurrence of the right mandibular swelling and generalised gingivitis were noted when the cat was 6 years of age and prescribed antibiotics (amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, 12.5 mg/kg PO q12h). The cat subsequently sustained a luxation of the right coxofemoral joint and was euthanased.

Case 3

A female neutered domestic longhair cat was rehomed as a young adult. The owner reported bilateral jaw abnormalities with skin defects and persistent deciduous teeth. Radiographs were not available for review; however, clinical records reported the presence of unerupted permanent teeth on radiographs. Surgery was performed to debride the proliferative bone of the mandibular jaw and to close the skin defects. Following surgery, the owner reported that the cat made a satisfactory recovery with a good quality of life. The cat developed a patellar fracture in the following year. No further follow-up information was available.

Case 4

A female neutered Siamese cross cat was rehomed from a rescue centre. Prior to being rehomed, a left unilateral mandibulectomy was performed to manage a presumed mandibular osteoma. Histopathology reports for this lesion were not available. At 2 years of age the cat developed left hindlimb lameness. Persistent deciduous teeth and generalised gingivitis were noted at presentation. Radiographs of the left hindlimb revealed a patellar fracture, which was surgically stabilised. The cat was euthanased after sustaining a humeral condylar fracture in the postoperative period following patellar fracture stabilisation.

Case 5

A male neutered DSH cat presented at 1 year and 8 months of age with severe generalised gingivitis, multiple persistent deciduous teeth and failure of eruption of permanent dentition. Surgical extraction of all persistent deciduous teeth was performed. Within the same month, the cat sustained a right patellar fracture, which was managed surgically. Five months following the right patellar fracture, a left patellar fracture was diagnosed and managed conservatively. At this time, the cat also presented with a recurrence of gingivitis and development of left mandibular swelling. Radiographs revealed marked irregular periosteal proliferation of the left mandibular body (Figure 2a,b). The lesion was classified as radiologically aggressive owing to the active periosteal reaction, and differential diagnoses included osteomyelitis, osteosarcoma, chondrosarcoma and multilobular tumour of bone. There was evidence of malformed, unerupted permanent maxillary canine teeth and unerupted permanent maxillary incisor teeth (Figure 2c).

Figure 2.

Radiographs from case 5. (a) Intraoral ventrodorsal mandibular radiograph and (b) lateral mandibular radiograph demonstrating marked irregular periosteal proliferation of the rostral left mandibular body. The periosteal reaction is thick and brush-like to palisading and considered radiologically aggressive. (c) Intraoral dorsoventral maxillary radiograph showing unerupted permanent canine teeth (arrowed)

The mandibular swelling persisted, despite medical management with antibiotics and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and the lesion was biopsied. Histopathological findings were consistent with osteomyelitis. A staged surgery was performed to extract the unerupted permanent mandibular teeth. The swelling gradually reduced in size over a period of 6 months with continued medical management of antibiotics and NSAIDs; however, following development of a pelvic fracture the cat was euthanased.

Case 6

A female entire DSH cat was rehomed at 4 months of age from a rescue centre. Left hindlimb lameness was noted at 5 months of age and radiographs demonstrated coxofemoral luxation; a femoral head ostectomy was performed. Sixteen months later the cat developed right hindlimb lameness and bilateral patellar fractures were diagnosed on radiographs; both were managed conservatively.

At 2 years of age the cat presented with a left mandibular swelling and multiple persistent deciduous teeth were noted. Skull radiographs showed marked irregular/brush-like and heterogeneous periosteal reaction with aggressive characteristics affecting the left mandibular body (Figure 3a). Differential diagnoses included osteomyelitis, osteosarcoma, chondrosarcoma and multilobular tumour of bone. Multiple unerupted permanent mandibular teeth were also observed. The cat was prescribed antibiotics (amoxicillin/clavulanic acid [12.5 mg/kg PO q12h] and enrofloxacin [5 mg/kg PO q24h]) and surgery was performed to debride the proliferative bone and extract the unerupted teeth (Figure 3b,c). Escherichia coli, Enterococcus species and Serratia marcescens were isolated on bacterial culture of the excised tissue. Bone biopsies were submitted for histopathological examination, which revealed periosteal woven bone proliferation and suppurative inflammation – findings consistent with osteomyelitis.

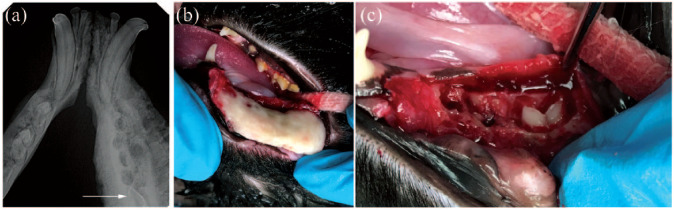

Figure 3.

Images from case 6. (a) Intraoral ventrodorsal mandibular radiograph showing marked periosteal reaction with aggressive characteristics affecting, in particular, the left mandibular body. The unerupted left first molar tooth is visible (arrowed). (b) Intraoperative photograph showing marked bony proliferation of the left mandibular body following elevation of a mucogingival flap. (c) Intraoperative photograph demonstrating an unerupted permanent first molar tooth following ostectomy of part of the proliferative mandibular bone and extraction of the premolar teeth

Following surgery, the mandibular swelling persisted and the cat developed an area of exposed necrotic mandibular bone and a left total mandibulectomy was performed. The left mandibular body was submitted for histopathology, which revealed marked, chronic pyogranulomatous osteomyelitis with bony proliferation. At the time of writing, treatment for this cat is ongoing.

Case 7

A female neutered Maine Coon cross cat presented at 10 months of age with multiple persistent deciduous teeth (Figure 4a), gingivitis and ventral mandibular swellings. Skull radiographs confirmed the presence of persistent deciduous teeth and unerupted permanent teeth (Figure 4b). Bilaterally, the mandibular bodies were thickened with a loss of normal corticomedullary definition. Multiple persistent deciduous teeth and unerupted permanent teeth were surgically extracted. Necrotic mandibular bone was debrided and samples submitted for histopathological examination. Histological findings were consistent with secondary osteonecrosis and suppurative osteomyelitis. The mandibular bone also exhibited features suggestive of a diagnosis of osteopetrosis, such as areas of increased bone density with abnormal organisation.

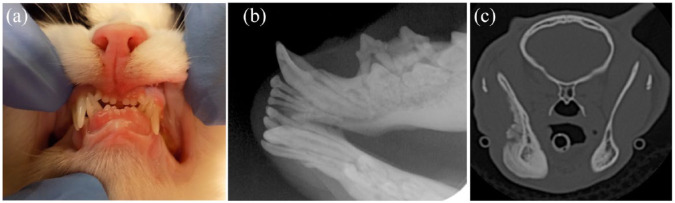

Figures 4.

Images from case 7. (a) Photograph showing multiple persistent deciduous teeth identified on clinical examination (teeth 504, 704, 701, 801, 802, 804). (b) Intraoral ventrodorsal mandibular radiograph illustrating persistent deciduous canine, third and fourth premolar teeth, unerupted permanent third and fourth premolar teeth, and an enlarged mid-mandibular body. (c) Transverse, bone window CT image at the level of the rostral mandibular rami, demonstrating a marked irregular periosteal reaction along the lateral and ventral margin of the right mandible

Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (20 mg/kg PO q12h) and robenacoxib (2 mg/kg PO q24h) were prescribed. Five months later, the cat developed left hindlimb lameness and radiographs demonstrated a chronic left patellar fracture with a fibrous union, which was conservatively managed.

Eight months following the initial presentation, a fluctuant swelling developed over the right side of the head. Intraoral examination of the right caudal mandible revealed areas of exposed necrotic bone, severe inflammation and a draining tract. The swelling was surgically incised, drained and flushed and the area of necrotic bone was debrided. Abscess material was cultured, Pasteurella and Actinomyces species were isolated and antibiotic therapy was initiated (amoxicillin/clavulanic acid [20 mg/kg PO q12h] and metronidazole [5 mg/kg PO q12h]). The areas of necrotic bone persisted despite antibiotic therapy and a CT scan of the head was performed. CT images demonstrated an aggressive, proliferative lesion of the right mandible, most consistent with osteomyelitis (Figure 4c). Multiple teeth were absent and several small hyperattenuating fragments were present within the right mandibular body, consistent with small foci of sequestered necrotic bone. Bilateral mandibular and medial retropharyngeal lymphadenomegaly was detected and considered reactive; however, cytological examination was not performed. The right parotid salivary gland was also enlarged, a possible indication of right parotid sialoadenitis. Further debridement of necrotic bone was performed and antibiotic therapy was continued. A resolution of the intraoral inflammation and exposure of necrotic bone was observed, and at the time of writing, treatment is ongoing.

Case 8

A female neutered DSH cat presented at 15 months of age with right hindlimb lameness. Multiple persistent deciduous teeth were noted on clinical examination. NSAIDs (meloxicam 0.05 mg/kg PO q24h) were prescribed and a mild improvement in lameness was observed. At 18 months of age the cat presented with left hindlimb lameness. Radiographs of the stifles revealed bilateral patellar fractures, which were surgically managed.

At 8 years of age the cat sustained fractures of the pelvis, including a right ilial body fracture, which was surgically stabilised.

At 9 years of age the cat presented with halitosis, gingivitis and a necrotic lesion on the ventral aspect of the left mandible. Persistent deciduous teeth associated with the localised area of gingivitis were extracted. Twelve months later the cat developed additional necrotic lesions, gingivitis and a swelling of the right mandibular ramus. NSAIDs (meloxicam 0.05 mg/kg PO q24h) and antibiotics (cefovecin 8 mg/kg SC) were administered. The necrotic lesions improved; however, swelling of right mandible remained. Skull radiographs showed both persistent deciduous teeth and unerupted permanent teeth, with evidence of tooth resorption in multiple arcades. Bony changes comprised mild thickening of the mandibular cortices and smooth periosteal reaction. These changes were considered relatively non-aggressive, most likely reflecting reactive inflammatory change, with marked osteomyelitis considered less likely. Abnormal dentition was surgically extracted and the necrotic bone debrided. Follow-up was performed 4 weeks after surgery and a persistent discharging sinus was reported; at time of writing, treatment is ongoing.

Case 9

A female neutered DSH cat presented at 11 months of age with difficulty walking. Persistent deciduous teeth were noted on clinical examination. Radiographs demonstrated bilateral olecranon fractures, a right patellar fracture and multiple rib fractures. Generalised increased radio-opacity and a lack of corticomedullary definition of the long bones were identified on radiographs. Haematology and serum biochemistry were within normal limits. The cat was managed conservatively with NSAIDs and significantly improved over a period of 3 months.

At 20 months of age, the cat developed a swelling of the right mandible. Radiographs of the skull demonstrated smooth, well-defined periosteal proliferation along the ventral aspect of the right mandibular body with differential diagnoses, including inflammatory/reactive change or low-grade chronic osteomyelitis. There was generalised increased opacity of the osseous structures, including the calvarial bone, mandibular cortices, vertebral bodies and the hyoid bones (Figure 5).

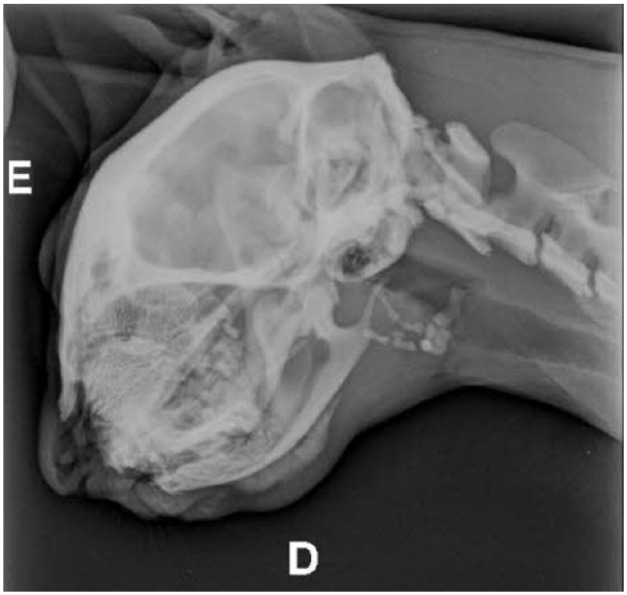

Figure 5.

Lateral skull radiograph from case 9 showing smooth, well-defined periosteal proliferation along the ventral aspect of the right mandibular body with generalised increased opacity of the osseous structures

Case 10

A female neutered DSH cat was rehomed at approximately 2 years of age and presented with right hindlimb lameness 3 days following rehoming. Persistent deciduous teeth were noted on clinical examination. Radiographs demonstrated a right patellar fracture, which was managed conservatively with NSAIDs (meloxicam 0.05 mg/kg PO q24h).

At 2 years and 2 months of age the cat developed a draining mandibular abscess and was prescribed NSAIDs (meloxicam 0.05 mg/kg PO q24h) and antibiotics (clindamycin 5.5 mg/kg PO q12h) for 1 week. An improvement was noted; however, the abscess recurred 3 months later. A mandibular molar tooth associated with the abscess was extracted and antibiotics (clindamycin 5.5 mg/kg PO q12h) were prescribed. Four weeks later, the cat presented with a mandibular swelling at the same site, together with halitosis and gingivitis. A 6 week course of antibiotics (clindamycin 5.5 mg/kg PO q12h) was prescribed; however, the mandibular swelling remained. Radiographs were obtained but were not available for review. Reports indicated the presence of persistent deciduous teeth and changes consistent with osteomyelitis and antibiotics were continued.

At 3 years and 6 months of age, the cat developed left hindlimb lameness and radiographs demonstrated pelvic fractures, which were managed conservatively. At 4 years and 6 months of age, the cat developed a right humeral condylar fracture, which was surgically stabilised. At 9 years of age the cat sustained a right calcaneal fracture and was euthanased.

Discussion

Mandibular and maxillary abnormalities in cats with ‘patellar fracture and dental anomaly syndrome’ (PADS) have not previously been reported. In cats, the process of exfoliation of primary teeth and eruption of permanent teeth is usually complete by 6 months of age. 6 Unlike dogs, deciduous teeth persisting beyond 6 months of age are rarely reported in the feline population and as such the incidence is poorly documented. One study describing dental pathology of adult feral cats from an inbred population on a sub-Antarctic island found the incidence of persistent deciduous teeth to be 2%. 7 While collating data from initial investigations on feline patellar fractures in 2009, it was found that 15% of cats with patellar fractures had persistent deciduous teeth. 1 Additionally, of the cases included in the initial survey, it was noted that a small number of these cats also presented with mandibular and maxillary abnormalities, prompting further investigation of this clinical presentation.

A key objective of this case series was to report the radiological features of mandibular and maxillary abnormalities in cats with this syndrome. Marked bony and periosteal proliferation was a common feature, with lesions being classified as radiologically aggressive in several cases. Osteomyelitis was considered a key differential diagnosis for these radiographic lesions, alongside neoplasia. Interestingly, one of the cats in this case series had previously undergone a unilateral mandibulectomy for management of a suspected osteoma. No radiographs or histopathology reports were available for this cat. However, considering the subsequent history of a patellar fracture, mandibular osteomyelitis would be a reasonable alternative differential diagnosis for the mandibular lesion. Dental abnormalities identified on radiographs included persistent deciduous teeth, hypodontia, root resorption, root malformation and unerupted permanent teeth. Head CT images were available for one cat and demonstrated findings consistent with ongoing osteomyelitis, despite surgical extraction of persistent deciduous and unerupted permanent teeth. Small hyperattenuating fragments were also identified within the most affected mandible and are suspected to be foci of sequestered necrotic bone acting as a nidus for infection.

Research is currently ongoing for cats with PADS to establish a genetic cause for the disorder. Biopsies of mandibular bone from one case demonstrated histological features of osteopetrosis. Osteopetrosis in humans is a rare genetic disorder characterised by reduced osteoclast-mediated bone resorption, leading to a net increase in bone density.8,9 Human patients with osteopetrosis have also been reported to suffer from persistent deciduous teeth and pathological fractures. Generalised increased bone opacity is not a common feature of this syndrome, but was observed for one case in the series, in which radiographs demonstrated increased radio-opacity of multiple skeletal structures, including long bones and bones of the skull. Furthermore, a recent case report documented how a cat receiving long-term oral bisphosphonates (inhibitors of osteoclastic bone resorption) developed bilateral patellar fractures in association with sclerosis of both patellae. 10 A degree of increased bone density can also be present without an abnormal radiological appearance.

Bone from patients with osteopetrosis is thought to have a reduced vascular supply and is therefore more prone to osteomyelitis. 8 In one human study, nearly two-thirds of patients with osteopetrosis autosomal dominant type II had oral manifestations, including mandibular osteomyelitis (11%). 11 In humans, mandibular osteomyelitis has been shown to be a destructive process requiring repeated surgeries and multiple courses of antibiotics. 11 For this case series, positive bacterial cultures were obtained for all cats where microbiology reports were available, and histopathology findings were consistent with osteomyelitis and osteonecrosis.

Treatment protocols were extremely variable for the 10 cats included in this case series; however, antibiotics and NSAIDs were administered in the majority of cases. Initial improvement of clinical signs was often observed; however, complete resolution of clinical signs was not a common feature for cats receiving solely medical management.

Deciduous teeth may persist for many years if their permanent counterparts are not present. 12 Physiological root ankylosis and resorption and tooth exfoliation often results. 12 Surgical extraction of unerupted permanent teeth is often recommended to prevent complications such as the development of dentigerous cysts.13,14 Interestingly, none of the cases reported here showed radiographic or histological signs of cystic development. Surgery was performed for 7/10 cats in this case series. Surgical procedures included extraction of persistent deciduous teeth, extraction of unerupted permanent teeth, debridement of proliferative and necrotic bone and in two cases a unilateral mandibulectomy.

Unfortunately, owing to the rarity of this condition, a limitation of this case series is the small number of cases included. Other limitations include the retrospective nature of the case series and variability of information in the case notes, particularly relating to details about specific tooth involvement. Furthermore, treatment protocols and quality of available images were variable. Long-term follow-up on surgical outcome was not available for many of the cats in the series, as cats were either lost to follow-up, euthanased following development of multiple limb or pelvic fractures, or treatment was ongoing at the time of data acquisition. Further research on long-term outcome is required.

Conclusions

Mandibular and maxillary abnormalities are an additional clinical feature of this disease that we have named PADS. It is therefore recommended that a thorough oral examination is performed in every cat diagnosed with atraumatic patellar fractures. Radiologically, these lesions can exhibit aggressive characteristics, which, owing to the rarity of this condition, may be misinterpreted as neoplastic disease. Additional diagnostic tests, such as microbiology and histopathology, are recommended to distinguish osteomyelitis from neoplasia. Treatment of osteomyelitis with targeted antimicrobial agents and anti-inflammatory medication is associated with short-term improvement of clinical signs. However, surgical extraction of persistent deciduous and unerupted permanent teeth, and debridement of proliferative and necrotic bone appears to be associated with an improved outcome. Aggressive surgical management such as mandibulectomy is not recommended as a first-line treatment but could be considered for cases where osteomyelitis is unresponsive to treatment.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the following veterinarians and owners who aided us with data collection relating to this case series: Victoria Darke, Pamela Taylor, Jim Perry, Indira Coomaraswamy, Casey Kersten, Kirsten Berggren, Mark Norcott, Adriana Silva Cristina and Patrick Ridge.

Footnotes

Accepted: 6 July 2018

Author note: These findings were presented as a clinical research abstract at the British Veterinary Orthopaedic Association’s spring meeting in April 2017.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Charlotte Howes  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5943-3618

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5943-3618

Natalia Reyes  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9939-2870

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9939-2870

References

- 1. Langley-Hobbs SJ. Survey of 52 fractures of the patella in 34 cats. Vet Rec 2009; 164: 80–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mason RW, Moore TE, Walker CW, et al. Patellar fatigue fractures. Skeletal Radiol 1996; 25: 329–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Longley M, Bergmann H, Langley-Hobbs SJ. Case report: calcaneal fractures in a cat. Companion Anim 2016; 21: 265–269. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Langley-Hobbs SJ, Ball S, McKee WM. Transverse stress fractures of the proximal tibia in 10 cats with non-union patellar fractures. Vet Rec 2009; 164: 425–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brooks TS, Bailey SJ. Knees & teeth case series presentation. http://www.toothvet.ca/PDFfiles/Feline_knees_and_teeth.pdf (2012, accessed August 20, 2018).

- 6. Orsini P, Hennet P. Anatomy of the mouth and teeth of the cat. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 1992; 22: 1265–1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Verstraete FJ, Van Aarde RJ, Nieuwoudt BA, et al. The dental pathology of feral cats on Marion Island, part I: congenital, developmental and traumatic abnormalities. J Comp Pathol 1996; 115: 265–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Krithika C, Neelakandan RS, Sivapathasundaram B, et al. Osteopetrosis-associated osteomyelitis of the jaws: a report of 4 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2009; 108: 56–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. White SC, Pharoah MJ. Systemic diseases manifested in the jaws. In: White SC, Pharoah MJ. (eds). Oral radiology. Principles and interpretation. 5th ed. St Louis, MO: Mosby, 2004, pp 516–537. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Council N, Dyce J, Drost WT, et al. Bilateral patellar fractures and increased cortical bone thickness associated with long-term oral alendronate treatment in a cat. JFMS Open Rep 2017; 3. DOI: 10.1177/2055116917727137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Benichou OD, Laredo JD, De Vernejoul MC. Type II autosomal dominant osteopetrosis (Albers-Schönberg disease): clinical and radiological manifestations in 42 patients. Bone 2000; 26: 87–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schroeder HE. Tooth eruption. In: Schroeder HE. (ed). Oral structural biology. Embryology, structure, and function of normal hard and soft tissues of the oral cavity and temporomandibular joints. Stuttgart and New York: Georg Thieme Verlag Stuttgart, 1991, pp 294–313. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Babbit SG, Krakowski M, Volker M, et al. Incidence of radiographic cystic lesions associated with unerupted teeth in dogs. J Vet Dent 2016; 33: 226–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Verstraete FJM, Zin BS, Kass PH, et al. Clinical signs and histopathologic findings in dogs with odontogenic cysts: 41 cases (1995–2010). J Am Vet Med Assoc 2010; 239: 1470–1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]