Abstract

Objectives

The aim of this study was to analyse the frequency of oral cavity lesions in cats, their anatomical location and histological diagnosis, and the effect of life stage, breed and sex on different diagnoses.

Methods

For this purpose, a retrospective study comprising 297 feline oral cavity lesions was performed over a 6-year period between 2010 and 2015. Histopathological records from the DNAtech Pathology Laboratory (Lisbon, Portugal) were analysed.

Results

The incidence of oral disease was higher in male cats (n = 173; 58.4%), mature adults (ranging from 7 to 10 years old [n = 88; 33.0%]) and in the European Shorthair breed (n = 206; 73.6%). The gingiva was the site where oral lesions were most commonly found, with 128 samples (43.1%). Incisional biopsies were used to obtain the majority of samples (n = 256; 86.2%), while excisional biopsies and punch biopsies were performed in 36 (12.1%) and five (1.7%) cases, respectively. Inflammatory and neoplastic lesions accounted for 187 (63%) and 110 (37%) of the studied cases, respectively. Malignancies were found in >80% of neoplastic cases. Feline chronic gingivostomatitis was the most common histological diagnosis (n = 116; 39.1%), followed by squamous cell carcinoma (n = 49; 16.5%) and eosinophilic granuloma complex (n = 33; 11.1%).

Conclusions and relevance

The present work, involving a large series of samples of feline oral cavity lesions, from numerous geographically scattered practices and all examined at a reference veterinary pathology laboratory, adds important new understanding of the epidemiology of feline oral disease.

Keywords: Oral cavity, histopathology, feline chronic gingivostomatitis, squamous cell carcinoma

Introduction

Feline oral cavity lesions are undeniably common in cats. The clinical signs are diverse and can include halitosis, decreased grooming, inappetence and anorexia, ptyalism or sialorrhoea, excessive pawing, oral cavity haemorrhage, teeth exfoliation and facial asymmetry, among others. Considering that cats usually show no clear clinical signs, feline oral cavity lesions are typically noted at an advanced clinical stage. In addition, even though some lesions are consequences of chronic diseases, others can develop suddenly. 1 For these reasons, systematic evaluations of oral cavity during routine visits are imperative for early diagnosis and proper management.2–4

Feline oral cavity lesions can be inflammatory or neoplastic in nature and their final diagnosis requires a histopathological examination. According to the literature, feline chronic gingivostomatitis (FCGS) is the most prevalent inflammatory disease,3,5,6 while eosinophilic granuloma complex (EGC) is the second most common inflammatory disease in cats.1,5,7 When clinical signs of inflammation are diffuse, FCGS and EGC may be clinically indistinguishable, although the correct therapeutic approach for each case is quite distinct. For this reason, the use of prompt microscopic examination is essential.1,8

Neoplastic feline oral cavity lesions account for 3–12% of all tumours in cats, of which up to 89% are malignant.9,10 Oral tumours are further classified into non-odontogenic (originating from oral cavity structures not associated with dental tissues) and odontogenic (originating from the epithelium and the embryonic mesenchyme later involved in tooth formation).10,11 Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the most common non-odontogenic malignant oral tumour in cats (60–80% of all oral tumours),5,9,10 followed by fibrosarcoma (FS; roughly 20% of all cases).5,6,12 Odontogenic tumours are rare in cats, accounting for up to 8% of all oral neoplasms.9,13 These are divided into peripheral odontogenic fibroma (POF), which may be fibromatous or ossifying, acanthomatous ameloblastoma and peripheral giant cell granuloma.10,13,14 The last, although not a true neoplastic lesion, behaves similarly to a tumour from a clinical perspective. For this reason, it has been included in this classification.15,16 Finally, the fibromatous form of POF is the most frequently diagnosed odontogenic tumour in cats. 16

The aim of this study was to assess the prevalence of oral diseases in Portuguese cats, over a 6-year period, in order to evaluate the distribution of inflammatory and neoplastic lesions, while simultaneously correlating them with sex, breed and life stage.

Materials and methods

Samples

In total, 297 surgically removed feline oral cavity lesions examined between 2010 and 2015 at the DNAtech Pathology Laboratory (Lisbon, Portugal) by an expert pathologist were included in this study. Samples in which no alterations were verified were excluded. All specimens were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin. After dehydration and embedding in paraffin, sections of 4 μm were cut from each representative paraffin block for haematoxylin and eosin staining.

Clinicopathological parameters

The following clinical parameters were evaluated: sex, life stage and breed, as well as the anatomical location of origin and the collection technique applied to obtain the samples. Sex was categorised as male or female. Information concerning neutering was not available.

For statistical purposes, life stages were divided into six groups: kitten (up to 6 months old), young (7 months to 2 years old), young adult (3–6 years old), mature adult (7–10 years old), senior (11–14 years old) and geriatric (from 15 years of age upwards). 17

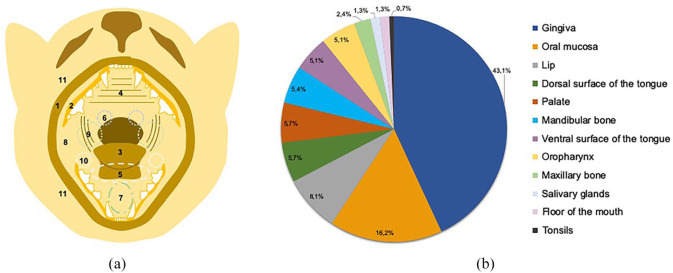

The anatomical location of the lesions was divided into floor of the mouth, gingiva, lip, mandible and maxillary bones, oral mucosa, oropharynx, palate, dorsal and ventral surfaces of the tongue, salivary glands and tonsils (Figure 1). Sample collection was performed using incisional biopsy, excisional biopsy or punch biopsy techniques.

Figure 1.

(a) Schematic image of the anatomical sites from where the studied samples were collected. (b) Relative distribution of oral lesions according to anatomical location.

1 = lip; 2 = gingiva; 3 = dorsal surface of the tongue; 4 = palate; 5 = ventral surface of the tongue; 6 = tonsils; 7 = floor of the mouth; 8 = oral mucosa; 9 = oropharynx; 10 = salivary glands; 11 = mandible and maxillary bones

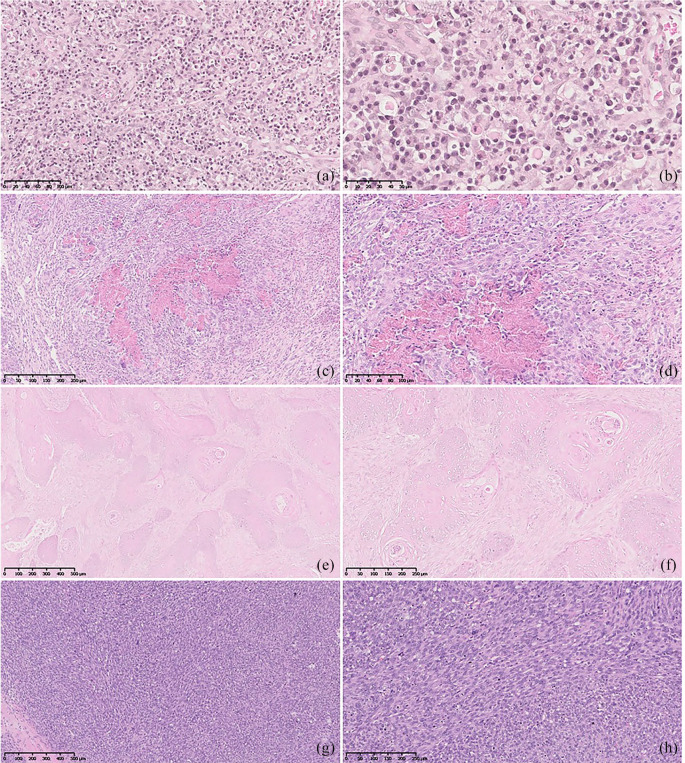

For each sample, data on the nature of the lesions and histopathological diagnosis were collected. Twenty-three histopathological diagnoses were found. These were first divided in accordance to their inflammatory or neoplastic nature. Inflammatory feline oral cavity lesions included FCGS (Figure 2a,b), EGC (Figure 2c,d), feline nasopharyngeal polyp, non-specific stomatitis, gingival hyperplasia, osteomyelitis, bone metaplasia, macule and pyogranulomatous sialadenitis. Neoplastic feline oral cavity lesions included peripheral odontogenic fibroma, peripheral giant cell granuloma, acanthomatous ameloblastoma, SCC (Figure 2e,f), adenocarcinoma, peripheral nerve sheath tumour, granular cell tumour, FS (Figure 2g,h), fibroma, osteoma, mast cell tumour, lymphoma, haemangioma and undifferentiated tumours.

Figure 2.

Photomicrographs depicting representative images (haematoxylin and eosin staining) of observed feline oral cavity lesions: (a,b) feline chronic gingivostomatitis; (c,d) eosinophilic granuloma complex; (e,f) squamous cell carcinoma; and (g,h) fibrosarcoma. Courtesy of Professor Maria dos Anjos Pires, Veterinary Sciences Department, Laboratory of Histology and Anatomical Pathology, UTAD, Portugal

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 22.0 (IBM). As most of the variables were categorical, inferential statistical analysis was performed using Pearson’s χ2 test.

Results

Clinical characterisation of the cats

This retrospective study included a total of 297 feline oral cavity lesions cases in owned pet cats. Of these, 173 (58.4%) were male, 123 (41.6%) were female and, in one case, no information on sex was available.

Regarding breed, from a total of nine pure breeds, European Shorthair cats were predominant (n = 206; 73.6%), followed by Persian (n = 32; 11.4%) and Siamese cats (n = 21; 7.5%). It was not possible to determine the breed of 17 cats in this study (Table 1).

Table 1.

Absolute and relative distribution of feline oral cavity lesions observed according to breed (n = 280)

| Breed | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| European Shorthair | 206 | 73.6 |

| Persian | 32 | 11.4 |

| Siamese | 21 | 7.5 |

| Norwegian Forest Cat | 9 | 3.2 |

| Maine Coon | 4 | 1.4 |

| Russian Blue | 3 | 1.1 |

| British Shorthair | 2 | 0.7 |

| Scottish Straight | 1 | 0.4 |

| Scottish Fold | 1 | 0.4 |

| Chartreux | 1 | 0.4 |

Concerning age, cats were stratified by well-recognised life stages. 17 Feline oral cavity lesions were predominantly present in mature adult cats (7–10 years old [n = 88; 32.9%]), followed by senior cats (n = 60; 22.5%), young adults (n = 48; 18.0%), young cats (n = 37; 13.9%), geriatric cats (n = 24; 9%) and, finally, kittens (n = 10; 3.7%). It was not possible to determine the age of 30 cats in this study.

Description of the oral lesion specimens

Regarding anatomical location (Figure 1b), the gingiva was the most common site for feline oral cavity lesions(n = 128; 43.1%), followed by the oral mucosa (n = 48; 16.2%) and the lip (n = 24; 8.1%). The incisional biopsy technique was used to collect 256 samples (86.2%). Less frequently, excisional biopsy (n = 36; 12.1%) and punch biopsy techniques (n = 5; 1.7%) were adopted to collect feline oral cavity lesions samples.

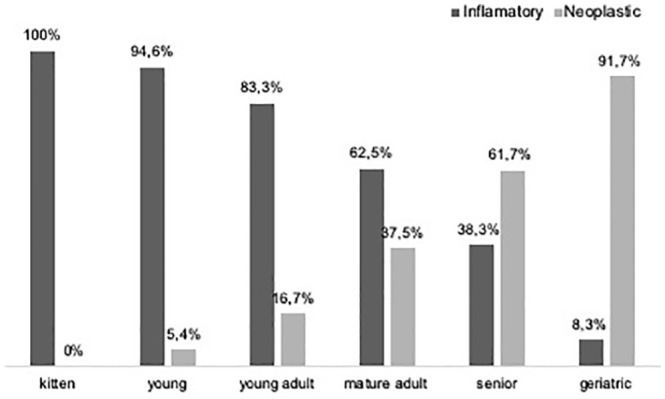

An inflammatory and neoplastic nature accounted for 187 (63%) and 110 (37%) cases among all feline oral cavity lesions studied, respectively. In kittens, up to 6 months of age, only inflammatory lesions were diagnosed. Young cats, young adults and mature adults showed a higher frequency of inflammatory lesions than neoplasms. Neoplastic lesions were diagnosed more frequently in senior and geriatric cats (Figure 3). Differences between the cats’ life stage and the nature of the lesions were found to be statistically significant (P <0.001).

Figure 3.

Relative distribution of inflammatory and neoplastic lesions according to life stage. Surprisingly, >15% of the cases among young adults were neoplastic, despite being more expected in senior and geriatric cats

Table 2 shows all diagnoses of feline oral cavity lesions reported in this study, such as fibroma, osteoma, lymphoma, mast cell tumour, haemangioma, granular cell tumour, feline nasopharyngeal polyps, bone metaplasia, macula, osteomyelitis and pyogranulomatous sialadenitis.

Table 2.

Absolute and relative distribution of the histopathological diagnoses obtained

| Diagnosis | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Feline chronic gingivostomatitis | 116 (39.1) |

| Feline eosinophilic complex | 33 (11.1) |

| Feline nasopharyngeal polyp | 3 (1.0) |

| Non-specific stomatitis | 21 (7.1) |

| Gingival hyperplasia | 10 (3.4) |

| Bone metaplasia | 1 (0.3) |

| Osteomyelitis | 1 (0.3) |

| Macule | 1 (0.3) |

| Pyogranulomatous sialadenitis | 1 (0.3) |

| Peripheral odontogenic fibroma | 5 (1.7) |

| Peripheral giant cell granuloma | 3 (1.0) |

| Acanthomatous ameloblastoma | 1 (0.3) |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 49 (16.5) |

| Adenocarcinoma | 6 (2.0) |

| Peripheral nerve sheath tumour | 9 (3.0) |

| Granular cell tumour | 1 (0.3) |

| Fibrosarcoma | 5 (1.7) |

| Fibroma | 2 (0.7) |

| Osteoma | 3 (1.0) |

| Mast cell tumour | 3 (1.0) |

| Lymphoma | 2 (0.7) |

| Haemangioma | 2 (0.7) |

| Undifferentiated tumours | 19 (6.4) |

Description of the inflammatory oral cavity lesions

FCGS was the most common histological diagnosis found overall (n = 116; 39.1%). It represented 62% of the studied inflammatory feline oral cavity lesions (Figure 2a,b). FCGS was most commonly found in the gingiva (n = 66), followed by oral mucosa (n = 22) and oropharynx (n = 12). Male cats (n = 63; 54.3%), between the ages of 7 and 10 years (n = 39; 32.8%), were most often diagnosed with FCGS. FCGS was most often seen in European Shorthairs (n = 91; 78.4%), followed by Persian cats (n = 13; 10.3%) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Absolute distribution of feline chronic gingivostomatitis, according to life stage, in European Shorthair, Persian and Siamese cats

| Kitten | Young | Young adult | Mature adult | Senior | Geriatric | Not determined | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| European Shorthair | 1 | 14 | 17 | 33 | 11 | 1 | 14 |

| Persian | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Siamese | − | − | − | 2 | 1 | − | − |

EGC was the third most common histological diagnosis found overall (n = 33; 11.1%). It was the second most common inflammatory feline oral cavity lesion diagnosed (17.6%) (Figure 2c,d). EGC comprised 23 eosinophilic ulcers and 10 eosinophilic granulomas. EGC was most commonly found in the lips (n = 12; 36.4%), followed by dorsal and ventral surfaces of the tongue (n = 5 each). Half of the cases occurred in European Shorthair cats (n = 15; 45.5%), followed by Persians (n = 8; 24.2%). There were a slightly higher number of EGC diagnoses in male cats (51.5%). The distribution of EGC was uniform between young cats and mature adult cats.

Description of neoplastic oral cavity lesions

From 110 feline oral cavity tumours found, 90 (81.8%) were malignant. A borderline statistically significant trend (P = 0.067) was observed regarding the relationship between the aggressiveness of the oral cavity tumour and the life stage of the cats.

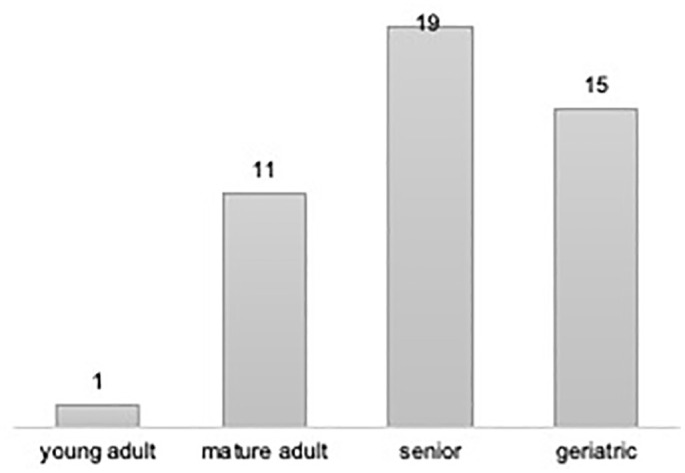

SCC was the most frequently diagnosed feline oral cavity tumour (n = 49) (Figure 2e,f). SCC was more commonly found in senior (n = 19; 38.8%) (Figure 4), European Shorthair (n = 31; 63.3%) and male (n = 26; 53.1%) cats. Gingival SCC (n = 18; 36.7%) was the most prevalent, followed by mandibular SCC (n = 10; 20.4%).

Figure 4.

Absolute distribution of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) according to life stage. No cases of SCC were found in kittens and only one in young adults cats

Five cases of FS were found (4.5%) (Figure 2g,h) among cats that were 3–14 years old and all were European Shorthair. FS were located in the gingiva (three cases), lip and maxillary bone (one case each).

Nine peripheral nerve sheath tumours were found (8.2%). Of these, seven were malignant and two were benign. Five peripheral nerve sheath tumours were found in male cats and four in female cats. Only mature adult and senior cats presented this type of tumours (50% each). Again, it was more often found in European Shorthair cats. Peripheral nerve sheath tumours were located in the gingiva (44.4%), but they were also found in the lip and in the palate.

Odontogenic tumours accounted for 8.2% of all neoplasms. Three fibromatous POFs and two ossifying POFs, two acanthomatous ameloblastoma and one peripheral giant cell granuloma were found. Odontogenic tumours were more often diagnosed in adult male European Shorthair cats (60%) and the gingiva was the most common location (80%).

Discussion

This study included 297 oral cavity lesions from cats. In accordance with previous studies, our results demonstrated that oral lesions were more common in mature adult male cats.5,6

Also, corroborating a recent study from 2019, inflammatory oral lesions were found in approximately 60% of the case series. 5 A study from 2018 showed a slightly lower percentage (51%) in a smaller population of cats (n = 73). 6 Our work showed that FCGS was the most common histological diagnosis for feline oral cavity lesions. According to previous studies, this disease tends to occur at a premature age in exotic cat breeds.3,18,19 Concerning life stage, among the three most prevalent breeds, namely European Shorthair, Persian and Siamese, mature adult cats were the most commonly afflicted. There was a trend showing a later diagnosis in European Shorthair vs Persian cats. Thus, it might be expected that inflammatory lesions would be more predominant in younger cats than in mature adult cats. In addition, it may be hypothesised that a late diagnosis is the cause of such a discrepancy. In our opinion, the histopathological diagnosis will probably not correspond to the beginning of the first clinical signs, which would, in turn, explain the fact that the age of diagnosis in cats is older than expected.3,4

EGC was the second most common inflammatory diagnosis found in the present work. 6 EGC was mostly found on the lips, followed by the dorsal surface of the tongue and floor of the mouth. Our data are in accordance with the literature;1,7,20 however, EGC has not often been described on the ventral surface of the tongue. 20

Previous studies state that tumours in the oral cavity in cats represent between 3% and 12% of all tumours in cats, 89% of which present a malignant behaviour.9,10 In this study, a similar percentage of neoplasms, roughly 80%, was identified as malignant. In agreement with the literature, SCC was the most prevalent tumour diagnosis in this study.5,6,9,10,21 Gingival SCC was predominant, followed by mandibular. SCC in the gingiva has been shown to be the most invasive. Owing to the proximity between the gingiva and bone tissue, SCC is commonly found in both locations.22,23 In line with our results, other groups have reported that SCC has a higher incidence in older cats.5,6,23,24

Although it has been found in some studies that oral FS represents approximately 20% of all oral neoplasms,9,24 recent studies5,6 present lower figures, supporting the results of the present study.

According to previous studies, the peripheral nerve sheath tumour was described to be rarer in oral locations (around 0.3–0.68%).6,9,13 While in the present study this tumour was present in up to 8.1% of the total number of neoplasms, immunohistochemistry panels would most likely help to diagnose the origin of poorly differentiated neoplastic feline oral cavity lesions were they to be routinely used.

Odontogenic tumours also accounted for 8.1% of all neoplasms. Of these, the peripheral odontogenic fibroma of the fibromatous type was predominant, in line with previous publications. 16 A gingival location, specifically the adjacent gingiva of the premolar and molar teeth,9,13 was the most frequently seen in our study. According to the literature, odontogenic tumours are found in cats ranging from 1 to 15 years of age.9,15,16 Our study showed that these benign tumours tend to occur in older cats, rather than in younger ones. This study reinforced the high incidence of malignancy, as well as the wide variety of neoplasms that can be found in the oral cavity of cats. 13 Diagnoses such as feline nasopharyngeal polyps, macula, osteomyelitis and pyogranulomatous sialadenitis were, indeed, uncommon in the oral cavity of cats.

As with any retrospective study, limitations may be found in our work, namely related to the quality of the clinical records provided by the practitioners. The relative proportion of lesions, in this type of study does not necessarily reflect the true distribution of lesions in the general feline population. Nevertheless, our results are in line with previous studies, adding more recent and clinically useful information.

Conclusions

The results of the present study show that inflammatory feline oral cavity lesions were more frequent than neoplasms. FCGS was the most frequent inflammatory feline oral cavity lesion and SCC was the most common neoplastic feline oral cavity lesion. We further confirm statistically significant differences between the life stages of cats and the histological diagnosis of oral diseases.

Footnotes

Accepted: 18 December 2019

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval: This work involved the use of non-experimental animal(s) only (owned or unowned) and followed established internationally recognised high standards (‘best practice’) of individual veterinary clinical patient care. Ethical approval from a committee was therefore not necessarily required.

Informed consent: This work did not involve the use of animals and therefore informed consent was not required. No animals or humans are identifiable within this publication, and therefore additional informed consent for publication was not required.

ORCID iD: Filipa Falcão  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7623-3746

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7623-3746

João Filipe Requicha  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9463-1625

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9463-1625

References

- 1. Lommer MJ. Oral inflammation in small animals. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2013; 43: 555–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bonello D. Feline inflammatory, infectious and other oral conditions. In: Tutt C, Deeprose J, Crosseley D. (eds). British Small Animal Veterinary Association manual of canine and feline dentistry. 3rd ed. Gloucester: British Small Animal Veterinary Association, 2007, pp 126–145. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Healey KAE, Dawson S, Burrow R, et al. Prevalence of feline chronic gingivo-stomatitis in first opinion veterinary practice. J Feline Med Surg 2007; 9: 373–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rolim VM, Pavarini SP, Campos FS, et al. Clinical, pathological, immunohistochemical and molecular characterization of feline chronic gingivostomatitis. J Feline Med Surg 2017; 19: 403–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mikiewicz M, Pazdzior-Czapula K, Gesek M, et al. Canine and feline oral cavity tumours and tumour-like lesions: a retrospective study of 486 cases (2015–2017). J Comp Pathol 2019; 172: 80–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wingo K. Histopathologic diagnoses from biopsies of the oral cavity in 403 dogs and 73 cats. J Vet Dent 2018; 35: 7–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Foster A. Clinical approach to feline eosinophilic granuloma complex. Comp Anim Pract 2003; 25: 2–9. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Buckley L, Nuttall T. Feline eosinophilic granuloma complex(ities): some clinical clarification. J Feline Med Surg 2012; 14: 471–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Stebbins KE, Morse CC, Goldschmidt MH. Feline oral neoplasia: a ten-year survey. Vet Pathol 1989; 26: 121–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Liptak JM, Withrow SJ. Cancer of the gastrointestinal tract – oral tumors. In: Withrow SJ, Vail DM, Page RL. (eds). Withrow & MacEwen’s small animal clinical oncology. 5th ed. St Louis, MO: Elsevier, 2013, pp 381–397. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rodrígues-Quirós J, Trobo J, San Román FSR. Neoplasias orales en pequeños animales. Cirurgía maxilofacial I. In: Ascaso FSR. (ed). Atlas de odontología en pequeños animales. Madrid: Grass Edicions, 1998, pp 143–161. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Morris J, Dobson J. Head and neck. In: Morris J, Dobson J. (eds). Small animal oncology. Oxford: Blackwell Science, 2001, pp 104–118. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Head KW, Cullen JM, Dubielzig RR, et al. Histological classification of tumors of the alimentary system of domestic animals. Second series. World Health Organization. Washington, DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Munday JS, Löhr CV, Kiupel M. Tumors of the alimentary tract. In: Meuten DJ. (ed). Tumors in domestic animals. 5th ed. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2017, pp 499–601. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Colgin LM, Schulman FY, Dubielzig RR. Multiple epulides in 13 cats. Vet Pathol 2001; 38: 227–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bruijn ND, Kirpensteijn J, Neyens IJS, et al. A clinicopathological study of 52 feline epulides. Vet Pathol 2007; 44: 161–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Vogt AH, Rodan I, Brown M, et al. Feline life stage guidelines. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2010; 46: 70–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Diehl K, Rosychuk RAW. Feline gingivitis-stomatitis-pharyngitis. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 1993; 23: 139–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wiggs RB. Estomatite linfocítica-plasmocítica. In: Norsworthy GD, Crystal MA, Tilley LP. (eds). O paciente felino. 2nd ed. São Paulo: Roca, 2009, pp 667–669. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bloom PB. Canine and feline eosinophilic skin diseases. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2006; 36: 141–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Soltero-Rivera MM, Krick EL, Reiter AM, et al. Prevalence of regional and distant metastasis in cats with advanced oral squamous cell carcinoma: 49 cases (2005–2011). J Feline Med Surg 2014; 16:164–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fondati A, Fondevila D, Ferrer L. Histopathological study of feline eosinophilic dermatosis. Vet Dermatol 2001; 12: 333–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Martin CK, Tannehill-Gregg SH, Wolfe TD, et al. Bone-invasive oral squamous cell carcinoma in cats: pathology and expression of parathyroid hormone-related protein. Vet Pathol 2011; 48: 302–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Head KW, Else RW, Dubielzig RR. Tumors of the alimentary tract. In: Meuten DJ. (ed). Tumors in domestic animals. 4th ed. Iowa City, IA: Iowa State Press, 2002, pp 401–482. [Google Scholar]