Abstract

Practical relevance:

Pet owners want dietary recommendations from their veterinarian. Providing a brief nutritional assessment for every cat at every visit will result in better medical care and build trust with clients.

Clinical challenges:

Examination time is limited, and it can be challenging to ensure appointments are efficient, yet thorough. A range of practical assessment tools is available that can assist with this process.

Patient group:

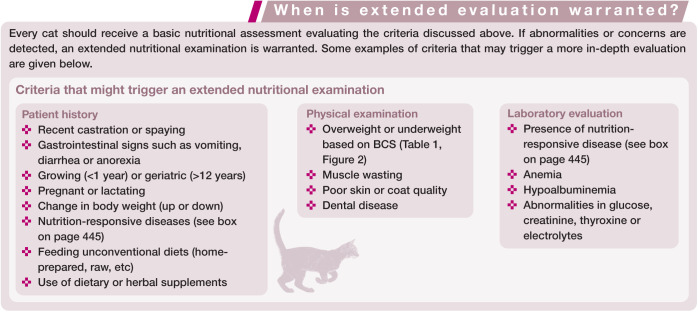

Every cat can benefit from a screening nutritional evaluation as the fifth vital assessment (after temperature, pulse, respiration and pain assessment). Identifying patients with nutritional risk factors or nutrition-responsive diseases should prompt a more in-depth review of dietary needs.

Audience:

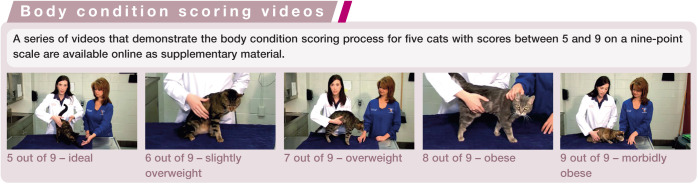

This article is aimed at all veterinary health professionals and is accompanied by videos demonstrating the body condition scoring process for a series of cats ranging from ideal body weight through to obese.

Evidence base:

Information in the review is drawn from the current scientific literature, as well as the clinical experience of the authors.

Keywords: Nutrition, diet, body condition score, nutritional assessment

Every cat, every veterinary visit

While all veterinary professionals (and likely most pet owners) would agree that nutrition is a key component of good health, many veterinarians feel ill-equipped to provide adequate nutritional assessments and recommendations for their patients. 1 According to the Pet Nutrition Alliance, 90% of pet owners reported wanting a nutritional recommendation from their veterinarian, but only 15% actually perceived receiving one. 2 In 2016 the global feline pet food market reached 26 billion US dollars. 3 With so much at stake, pet owners can be heavily influenced by the marketing claims of pet food manufacturers. Therefore, it is essential that veterinarians provide guidance based on evidence-based nutrition. Key to this are nutritional assessments for every cat at every visit to educate clients regarding the specific nutritional needs of their pet.

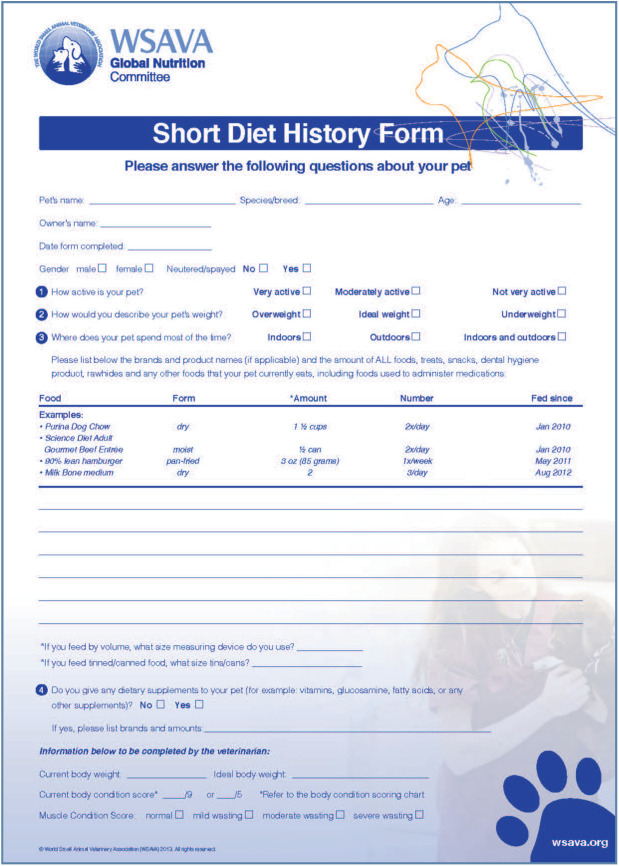

A nutritional assessment can be a fast and easy process that utilizes the entire veterinary team. To maximise efficiency, a nutritional history form (Figure 1) should be provided to pet owners for completion prior to their appointment; either it can be posted or emailed in advance or handed out at check-in for completion while they wait for the veterinarian. In addition, clients may be asked to bring along to the appointment a picture on their phone of their current cat food. Once completed, the history form can be reviewed by the veterinarian or a trained veterinary technician.

Figure 1.

Example of a short nutritional history form that can be completed by pet owners prior to the appointment. Part of a suite of resources within the WSAVA’s ‘Global Nutrition Toolkit’, the form is available to download from www.wsava.org/Guidelines/Global-Nutrition-Guidelines.

Image courtesy of the World Small Animal Veterinary Association

Three aspects are evaluated when performing a nutritional assessment: patient, diet and environment.4,5 While a few quick screening questions will provide adequate evaluation for most healthy pets (Figure 1), the presence of nutritional risk factors or nutrition-responsive diseases necessitates more in-depth review.

Assess the cat

The first step in providing a nutritional assessment is to examine the cat. Veterinarians are classically trained to record temperature, pulse, respiration and pain as vital assessments. Nutritional status is also now recommended as a fifth vital assessment to evaluate for every patient. 5 Patient characteristics to consider in the nutritional evaluation include age and physiologic status, activity, body condition score, muscle condition and nutrient-responsive disorders.

Age and physiologic status

Nutrient and energy requirements vary tremendously with age. Compared with adult cats, growing kittens need a calorically dense food with higher concentrations of vitamins and minerals such as calcium, phosphorus and vitamin D. 6 A diet meeting the Association of American Feed Control Officials (AAFCO) recommendations for growth is best for kittens. The age at which cats should transition from kitten to adult feline food is debatable, but 9–12 months is an appropriate period for most.

Spaying and castration can also increase the appetite and lower the energy needs of cats. 7 Therefore, owners should be counseled on ideal body condition at the time of surgical discharge and directed to switch to a lower calorie kitten food if their pet becomes overweight. Adult cat foods or those designed for weight loss may not meet nutritional requirements for growth and should not be used prior to skeletal maturity.

The nutrient needs of adult cats also change as they become geriatric (ie, >12 years). While the energy needs of most animals decrease later in life, some elderly cats require more energy to maintain their body weight. In approximately 30% of cats older than 12 years of age fat absorption is decreased, and in 20% protein digestibility is decreased. 8 This attenuated digestion can also lead to deficiencies in other vitamins and minerals. 8 To compensate for impaired nutrient absorption, elderly cats tend to eat more food relative to their body weight than younger cats. 9 Healthy geriatric cats with weight loss benefit from highly digestible, calorically dense diets that are higher in fat and protein. Changes in diet should be made gradually to prevent gastrointestinal upset. Some geriatric cats may be unable to tolerate energy-dense diets if excess nutrients reach the colon, where they can be fermented.

In addition to age, physiologic processes such as pregnancy and lactation also change the nutrient needs of cats. Adult cats in either of these life stages should have their diet and body condition scores (see below) closely monitored to ensure that adequate nutrition and calories are provided.

Activity

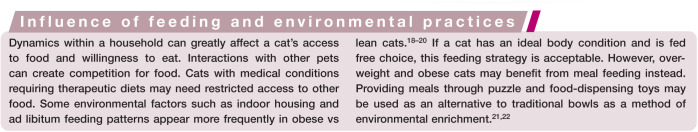

While not specifically studied, it is reasonable to assume that most outdoor cats have higher overall activity levels compared with indoor cats. Activity also decreases with age in indoor cats. 10 Activity patterns should be assessed for individual patients and food intake increased or decreased accordingly.

Body condition

A key component of the physical examination should be an assessment of body condition. Body condition scoring (BCS) is a method for estimating body fat mass based on a combination of visual assessment and palpation (Table 1; Figure 2). The veterinarian can use either a five- or nine-point scale in which 1 is cachexic and 5 or 9 is obese.11,12 Each point on the BCS scales correlates with a percentage range of body fat.

Table 1.

Descriptions of body condition scoring systems and their approximate correlations with body fat percentage11,12

| Five-point scale | Nine-point scale | % body fat | Body condition scoring |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | ≤5 | Emaciated – ribs and bony prominences are visible from a distance. No palpable body fat. Loss of muscle mass |

| 2 | 2 | 6–9 | Very thin – ribs and bony prominences visible. Minimal loss of muscle mass but no palpable fat |

| 3 | 10–14 | Thin – ribs easily palpable, tops of lumbar vertebrae are visible. Obvious waist and may have an abdominal tuck | |

| 3 | 4 | 15–19 | Lean – ribs easily palpable, waist visible from above. Abdominal fat may be present or absent. If present, it is made up of loose skin and no fat within |

| 5 | 20–24 | Ideal – ribs palpable without excess fat covering. Cats have a waist and a minimal abdominal fat pad | |

| 4 | 6 | 25–29 | Slightly overweight – ribs have slight excess fat covering. Waist is discernible from above but not obvious. Abdominal fat pad is apparent but not obvious |

| 7 | 30–34 | Overweight – difficult to palpate ribs. Moderate abdominal fat pad and rounding of the abdomen | |

| 5 | 8 | 35–39 | Obese – ribs not palpable, and abdomen may be rounded. Prominent abdominal fat pad and lumbar fat deposits. Fat deposit may be obvious in shoulder or abdominal area |

| 9 | 40–45+ | Morbidly obese – heavy fat deposits over lumbar area, face and limbs. Large abdominal fat pad and rounded |

Figure 2.

Nine-point body condition scoring chart.

From the Global Nutrition Toolkit, provided courtesy of the World Small Animal Veterinary Association

Ideally, body fat composition in cats ranges from 15–24%. 13 It is important to note that many obese cats may exceed the body fat percentages applicable to current BCS systems (>45% body fat). Therefore, additional assessment of body fat index (BFI) may be warranted for overweight and obese cats (Table 2). 14 Utilizing this system of assessment allows clinicans to estimate body fat percentages in even the most obese cases; this in turn will aid both client communication (eg, your cat is 60% body fat and should ideally be closer to 20% fat) and estimations of ideal body weight using the formula:

Table 2.

Body fat index (BFI) system for assessing overweight and obese cats

| BFI 30:

26–35% body fat |

BFI 40:

36–45% body fat |

BFI 50:

46–55% body fat |

BFI 60:

56–65% body fat |

BFI 70:

>65% body fat |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Face | Slight fat cover; defined bony structures on palpation | Slight to moderate fat cover; defined to slight bony structures on palpation | Moderate fat cover; slight to minimal bony structures on palpation | Thick fat cover; minimal to no palpable bony structures | Very thick fat cover; no palpable bony structures |

| Head and neck | Clear distinction between head and shoulder; loose scruff; slight scruff fat | Clear to slight distinction between head and shoulder; loose to snug scruff; slight to moderate scruff fat | Minimal distinction between head and shoulder; loose to snug scruff; slight to moderate scruff fat | Poor to no distinction between head and shoulder; snug to tight scruff; moderate to very thick scruff fat | No distinction between head and shoulder; tight scruff; very thick scruff fat |

| Sternum | Defined, slightly prominent; easy to palpate; slight to moderate pectoral fat | Minimally prominent; palpable; moderate pectoral fat | Poorly defined to not prominent; difficult to palpate; moderate to thick pectoral fat | Not prominent; very/extremely difficult to palpate; very/extremely thick pectoral fat | Not prominent; impossible to palpate; extremely thick pectoral fat |

| Scapula | Defined, slightly prominent; easy/very easy to palpate | Slightly prominent; easy to palpate | Minimally to not prominent; palpable | Not prominent; difficult to palpate | Not prominent; impossible to palpate |

| Ribs | Not prominent; easy to palpate | Not prominent; palpable | Not prominent; difficult to palpate | Not prominent; extremely difficult to impossible to palpate | Not prominent; impossible to palpate |

| Abdomen | Loose abdominal skin with minimal fat; easy to palpate abdominal contents | Obvious skin fold with moderate fat; easy to palpate abdominal contents | Heavy fat pad; difficult to palpate abdominal contents | Very heavy fat pad; indistinct from abdominal fat; impossible to palpate abdominal contents | Extremely heavy fat pad; indistinct from abdominal fat; impossible to palpate abdominal contents |

| Tail base | Slightly to minimally prominent bony structure; palpable; slight fat cover | Slightly to minimally prominent bony structure; palpable; slight to moderate fat cover | Poorly defined bony structure; difficult to palpate; moderate to thick fat cover | Bony structure very/extremely difficult to palpate; very thick to extremely thick fat cover | Bony structure very/extremely difficult to palpate; extremely thick fat cover |

| Shape from behind | Clear to poor muscle definition under a thin to moderate layer of fat | Poor muscle definition under a moderate layer of fat | Rounded appearance; thick layer of fat | Rounded to square appearance; thick layer of fat | Square appearance; very thick layer of fat |

| Shape from the side | No abdominal tuck | Slight abdominal bulge | Moderate abdominal | Severe abdominal bulge | Very severe abdominal bulge |

| Shape from above | Slight hourglass/straightening of waist with no hourglass indentation | Straightening of waist with no hourglass indentation and/or mild distension of the abdomen | Broadened back | Severely broadened back | Extremely broadened back |

BFI system validated as a method to estimate body composition in overweight and obese cats 14

Muscle condition

Muscle condition should be assessed and described separately from body condition score as cats may be overweight, yet suffer from muscle loss. Palpation of musculature over the skull, scapula, spine and wings of the ilia can be performed using a 0–3 point scale, with categories defined as severe muscle wasting (0), moderate muscle wasting (1), mild muscle wasting (2) or normal musculature (3). 15 Patients with reduced muscle condition should receive further medical and nutritional evaluation to determine the etiology of muscle loss.

Nutrition-responsive disorders

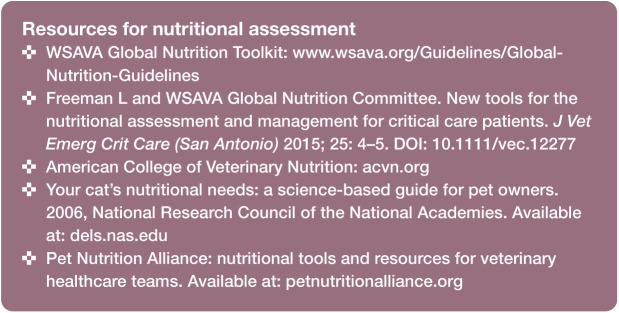

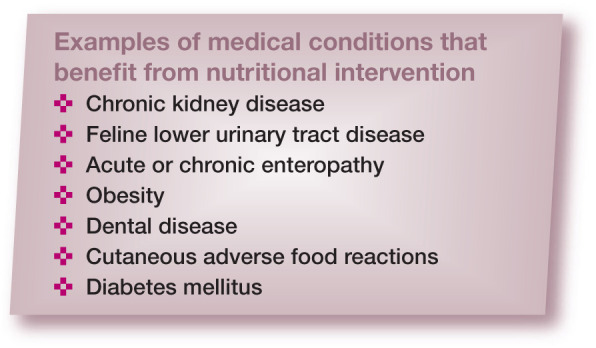

Cats suffering from diseases that may benefit from dietary intervention should have an in-depth nutritional evaluation performed. Examples of medical conditions that warrant nutritional intervention are given in the box below.

Assess the diet

Assessing the quality of a diet based on packaging claims, ingredient lists or the guaranteed analysis is difficult. The AAFCO has established standards and regulations regarding animal feed and so one method for assessing the quality of a cat food brand in North America is to look for an AAFCO statement on the package. Foods can either undergo a standard AAFCO feeding trial or be formulated to meet AAFCO nutrient requirements. Feeding trials are considered the gold standard because they test nutrient bioavailability.

In addition to reading the AAFCO statements, when available, before selecting a food brand the veterinarian and cat owner should also rely on company reputation and look for those with good quality control and safety measures. Calling manufacturers directly to determine the credentials of the persons formulating their diet and steps they take to ensure their diets meet post-production safety and nutrient requirements can provide insight into the quality level of the company. Ideally, individuals with advanced degrees or board certification in animal nutrition should be responsible for cat food formulations. Reputable companies will also provide full nutrient profiles of their products when requested.

Some owners prepare their cat’s food themselves and do not feed commercially manufactured diets. Nutritional imbalances can have severe health consequences. Home-prepared diets for cats are often deficient in calcium, iron, zinc and vitamin E, and thiamine, which can result in bone fractures / deformities, anemia, skin disorders and neurologic disease, respectively. 16 If cat owners insist on feeding home-prepared diets, veterinarians should recommend consultation with a board-certified veterinary nutrition specialist. A list of ACVN and ECVCN diplomates providing consultations can be found at www.acvn.org and www.esvcn.eu/college, respectively.

Feeding diets containing raw meat ingredients is another popular trend that should stimulate veterinarians to have a more detailed nutrition discussion with cat owners. A comprehensive review of the pros and cons of raw food feeding in pets is available. 17 Briefly, the risks of feeding undercooked meat with pathogenic bacteria extend to both pets and human household members. At this time, the documented benefits of feeding raw meat do not justify the potential health risks. Assuming companies utilize good manufacturing practices, some processes that destroy bacteria without using heat, for example high-pressure pasteurization, may provide viable alternatives for cat owners wanting to feed raw meat-based diets. However, dehydration and freeze-drying methods are not effective for killing many forms of pathogenic bacteria.

When assessing feeding management (see box below), it is also important to quantify current calorie content, especially for under-or overweight cats. The calorie content of cat food is now a labeling requirement of AAFCO and available on most company websites. Clients may be given a target calorie intake and asked to calculate their cat’s food volume based on the labeled calories per cup or gram. Alternatively, a member of the veterinary team can calculate food volumes for the client. Table 4 lists estimated energy needs of cats based on their ideal weight.

Table 4.

Estimated daily kilocalorie requirements for adult cats

| Ideal weight (kg/lb) | Obese-prone | Neutered | Intact |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3/6.6 | 160 | 192–225 | 225–255 |

| 4/8.8 | 200 | 240–280 | 280–320 |

| 5/11 | 235 | 280–330 | 330–376 |

| 6/13.2 | 271 | 325–380 | 380–433 |

| 7/15.4 | 300 | 360–420 | 420–480 |

Estimated daily energy requirements of adult cats are calculated using resting energy requirements of (body weight [kg]0.75)*70 and multiplying by a lifestage factor of 1.0 for obese-prone, 1.2–1.4 for neutered and 1.4–1.6 for intact cats. Energy requirements for active weight loss may require a factor lower than 1.0. Note these are guidelines only and individual cats may need more or less energy to maintain ideal body condition

Incorporating nutritional assessment into daily practice

Incorporating nutritional assessments into everyday practice is a team effort. Veterinarians, technicians and front desk staff should all work together to collect accurate information and provide clear recommendations.

Suggested steps for incorporating nutritional assessments into practice include:

Mailing or emailing a nutritional history form with each appointment reminder.

Requesting owners complete a nutritional history form prior to their visit or while in the waiting room.

Having a veterinary technician review the nutritional history form with the owner and calculate current calorie intake.

Placing the nutritional history into the medical record.

Including a body condition and muscle condition evaluation and making nutritional recommendations during the veterinary consultation (written recommendations should be provided if the feeding plan is changed).

Following up with the owner by a veterinary technician to ask if there are any questions about the feeding plan and to provide informational handouts, brochures, measuring cups, and so on, if required.

Dispensing of recommended food by front desk staff, if sold within the hospital, and answering any remaining questions.

Whenever new food is dispensed or recommended, having front desk staff or a veterinary technician call or email the owner a few days later to see if the changes are accepted.

Key Points

Nutrition affects the health of every cat.

It is the veterinarian’s responsibility to provide evidence-based nutritional assessments and plans for every patient at every visit. Otherwise, marketing and misinformation will guide cat owners’ decisions, often to the detriment of their pet.

To increase efficiency and reinforce messages, veterinary practices should approach nutritional assessments as a team.

Every cat should receive a screening assessment, while those with nutritional risk factors require evaluation that is more detailed.

Footnotes

Supplementary material: A series of videos that demonstrate the body condition scoring process for five cats with scores between 5 and 9 on a nine-point scale.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: AWR has grants from Royal Canin, Hill’s Pet Nutrition and Vet Innovations; MM’s position is partially funded by, and MM is in receipt of grants from, Royal Canin.

References

- 1. Buffington CA, LaFlamme DP. A survey of veterinarians’ knowledge and attitudes about nutrition. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1996; 208: 674–675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pet Nutrition Alliance. Tips for implementing nutrition as a vital assessment in your practice. http://www.wsava.org/sites/default/files/PNA_TipsGuide_WSAVAproof2.pdf (accessed March 11, 2019).

- 3. Phillips-Donaldson D. Global pet food sales update: ending 2016. on a high note. https://www.petfoodindustry.com/blogs/7-adventures-in-pet-food/post/6207-global-pet-food-sales-update-ending-2016-on-a-high-note (2017, accessed November 14, 2018).

- 4. Baldwin K, Bartges J, Buffington T, et al. AAHA nutritional assessment guidelines for dogs and cats. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2010; 46: 285–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Freeman L, Becvarova I, Cave N, et al. ; WSAVA Nutritional Assessment Guidelines Task Force. WSAVA nutritional assessment guidelines. J Feline Med Surg 2011; 13: 516–525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. National Research Council. Nutrient requirements of dogs and cats. Washington DC: National Academies Press, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Flynn MF, Hardie EM, Armstrong PJ. Effect of ovariohysterectomy on maintenance energy requirements in cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1996; 209: 1572–1581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Laflamme DP. Nutrition for aging cats and dogs and the importance of body condition. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2005; 35: 713–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Harper EJ. Changing perspectives on aging and energy requirements: aging and digestive function in humans, dogs and cats. J Nutr 1998; 128 Suppl 12: 2632–2635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Naik R, Witzel A, Albright J, et al. Pilot study evaluating the effect of feeding method on overall activity of neutered indoor pet cats. J Vet Behav 2019; 25: 9–13. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Laflamme D. Development and validation of a body condition score system for cats: a clinical tool. Feline Pract 1997; 25: 13–17. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Toll PW, Yamka RM, Schoenherr WD, et al. (eds). Small animal clinical nutrition. Topeka, Kansas: Mark Morris Institute, 2010, pp 501–542. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cline M, Witzel A, Moyers T, et al. Body composition of lean outdoor intact cats vs lean indoor neutered cats using dual energy x-ray absorp-tiometry. J Feline Med Surg. Epub ahead of print 1 June 2018. DOI: 10.1177/1098612X18780872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Witzel AL, Kirk CA, Henry GA, et al. Use of a morphometric method and body fat index system for estimation of body composition in overweight and obese cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2014; 244: 1285–1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Michel KE, Anderson W, Cupp C, et al. Correlation of a feline muscle mass score with body composition determined by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry. Br J Nutr 2011; 106 Suppl 1: 57–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pedrinelli V, Gomes MOS, Carciofi AC. Analysis of recipes of home-prepared diets for dogs and cats published in Portugese. J Nutr Sci 2017; 6. DOI: 10.1017/jns.2017.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Freeman LM, Chandler ML, Hamper BA, et al. Current knowledge about the risks and benefits of raw meat-based diets for dogs and cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2013; 243: 1549–1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Russell K, Sabin R, Holt S, et al. Influence of feeding regimen on body condition in the cat. J Small Anim Pract 2000; 41: 12–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Harper EJ, Stack DM, Watson TD, et al. Effects of feeding regimens on bodyweight, composition and condition score in cats following ovariohys-terectomy. J Small Anim Pract 2001; 42: 433–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kienzle E, Bergler R. Human-animal relationship of owners of normal and overweight cats. J Nutr 2006; 136 Suppl 7: 1947–1950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dantas LM, Delgado MM, Johnson I, et al. Food puzzles for cats: feeding for physical and emotional wellbeing. J Feline Med Surg 2016; 18: 723–732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sadek T, Hamper B, Horwitz D, et al. Feline feeding programs: addressing behavioral needs to improve feline health and wellbeing. J Feline Med Surg 2018; 20: 1049–1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]