Abstract

Aim:

This study sought to identify groups of colorectal cancer patients based upon trajectories of fatigue and examine how demographic, clinical, and behavioral risk factors differentiate these groups.

Method:

Patients were from six cancer centers in the United States and Germany. Fatigue was measured using the fatigue subscale of the EORTC-QLQ-C30 at five time points (baseline/enrollment, 3-, 6-, 12-, and 24-months after diagnosis). Piecewise growth mixture models identified latent trajectories of fatigue. Logistic regression models examined differences in demographic, clinical, and behavioral characteristics between fatigue trajectory groups.

Results:

Among 1,615 participants (57% male, 86% Non-Hispanic White, M age = 61±13 years at diagnosis), three distinct groups were identified. In the high fatigue group (36%), fatigue significantly increased in the first 6 months after diagnosis and then showed statistically and clinically significant improvement from 6 to 24 months (p values < 0.01). Throughout the study period, average fatigue met or exceeded cutoffs for clinical significance. In the moderate (34%) and low (30%) fatigue groups, fatigue levels remained below or near population norms across the study period. Patients who were diagnosed with stage II-IV disease, and/or current smokers were more likely to be in the high fatigue than in the moderate fatigue group (p values < 0.05).

Conclusion:

A large proportion of colorectal cancer patients experienced sustained fatigue after initiation of cancer treatment. Patients with high fatigue at the time of diagnosis may benefit from early supportive care.

Keywords: multicenter consortium, quality of life, fatigue, growth mixture models, longitudinal study design, colorectal cancer

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) and its treatment can lead to distressing symptoms and deteriorating quality of life (QoL) [1, 2]. Fatigue is among the most frequently reported symptoms in patients with cancer [3, 4]. Compared to other cancer-related symptoms such as pain and nausea, fatigue has a greater negative impact on daily activities and QoL [4–6]. Fatigue can persist for months or years following cancer diagnosis [7, 8]; late-onset fatigue has also been documented among post-treatment cancer survivors [9–11].

Despite a wealth of evidence about the severity and impact of cancer-related fatigue among patients with other common cancer types (e.g., breast, prostate, lung), little is known about fatigue in CRC patients [12]. Cross-sectional studies indicate that in general about half of patients with CRC reported some degree of fatigue [13, 14], with 26.8% reporting clinically significant fatigue [13]. A recent meta-analysis of symptomatology among CRC patients reported that fatigue was the most severe symptom following CRC treatment [1]. However, few longitudinal studies have examined changes in fatigue among CRC patients from diagnosis through treatment and survivorship [8, 15–17]. Previous studies with limited sample suggested that the prevalence and severity of fatigue increased immediately after treatment until 6 months [2], then decreased thereafter; at 24 months, fatigue recovered toward the pretreatment levels [15]. Further research with larger sample sizes and data beyond 6-month after the initiation of treatment is needed to investigate the heterogeneity and risk factors of trajectories in fatigue among CRC patients over time. Findings from these studies of cancer-related fatigue can provide evidence and rationale for targeted care interventions to reduce adverse effects of CRC and its treatment.

The purpose of this study was to examine the heterogeneity in changes of patient-reported fatigue following CRC diagnosis, and to identify baseline demographic, clinical, and behavioral characteristics as predictors of fatigue trajectories. It was hypothesized that at least two latent trajectories of fatigue would be identified among two years after diagnosis, and those trajectories would be associated with demographic, clinical, and behavioral characteristics.

Method

Study Population

This is a longitudinal study using data from a larger ColoCare Study. Participants were eligible if they: a) were at least 18 years of age at time of diagnosis, b) were newly diagnosed with colon, rectum, or rectosigmoid cancer (ICD-10 C18-C20) and had stage I-IV CRC based on the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) tumor/node/metastasis (TNM) classification, c) had been diagnosed by, was consulting with, and/or was receiving surgery or other cancer treatment from a physician collaborating with the ColoCare Consortium [18], d) were able to read and speak English (US sites) or German (German site), and e) had no mental or physical disabilities that limited their ability to consent or participate at the discretion of clinical and research team of ColoCare Consortium.

Procedure

Participants were recruited as part of the ColoCare Study cohort (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02328677), a large, multicenter, international prospective cohort investigating multilevel factors relevant to CRC survivorship between December 2009 and March 2021. Details regarding the study design and eligibility criteria have been described previously [18–22]. Participants included in the current analyses were recruited at six sites: H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute (Moffitt, Tampa, FL, USA); University of Tennessee Health Science Center (UTHSC, Memphis, TN, USA); Washington University School of Medicine (WUSM, St. Louis, MO, USA); Huntsman Cancer Institute (HCI, Salt Lake City, UT, USA); Cedars-Sinai Medical Center (Cedars, Los Angeles, CA, USA) and University of Heidelberg (HBG, Heidelberg, Germany). Patients meeting inclusion criteria were enrolled shortly after diagnosis (prior to surgery or treatment). Baseline data were collected shortly after diagnosis, approximately at the initiation of CRC treatment. Follow-up surveys were completed at 3-, 6-, 12-, and 24 months later. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the respective recruitment sites, and all patients provided written informed consent. All data and samples were centrally harmonized according to standardized protocols and standard operating procedures across all institutions.

Measures

Demographic and behavioral characteristics.

Age at diagnosis, sex at birth, race/ethnicity, body mass index (BMI, Kg/m2), and smoking status at recruitment were collected via questionnaires at enrollment and/or via a medical record review.

Fatigue.

Fatigue was measured at five time points (baseline, 3, 6, 12, and 24 months) at most sites (not including the 3-month follow-up at HCI and 24-month follow-up at UTHSC). Fatigue was assessed with the 3-item fatigue subscale of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC-QLQ-C30) [23]. The EORTC QLQ-C30 is a valid, reliable, and sensitive measure of fatigue in cancer research [24, 25]. Raw scores were transformed into a total score ranging from 0 to 100 [26]. Higher scores indicated worse fatigue. Previous research indicates the normative EORTC-QLQ-C30 fatigue score in general population is 29.5 [27], the threshold for clinically significant fatigue is 39 [28], and differences of 10 points or more are considered clinically meaningful [29]. Fatigue was not assessed at 3-month follow-up at one center and 24-month follow-up at another center; thus, these data were treated as missing.

Clinical characteristics.

Stage at diagnosis, primary tumor site, and neoadjuvant and adjuvant cancer treatments were abstracted from medical records. Patients were grouped by cancer stage at diagnosis (I, II, III, and IV—before receipt of any treatment), tumor site (based on ICD-10 codes), neo-adjuvant treatment, and adjuvant treatment. Specific treatment regimens and dates were not available.

Data Analysis

Analyses included participants who completed the fatigue subscale of the EORTC-QLQ-C30 at any time point. Descriptive statistics were used to describe baseline demographic, behavioral, and clinical characteristics, and fatigue over time. Piecewise growth mixture models (GMM) with 1 to 4 classes were fitted to identify latent subgroups of patients with distinct trajectories of fatigue [30]. Consistent with previous research [15], time was segmented into two parts: a period corresponding to when patients were expected to be on treatment (i.e., baseline, 3 months, and 6 months later) and a period corresponding to when they were expected to have finished treatment (i.e., 12 and 24 months after baseline). GMM used all available data at each time point. The optimal number of latent classes was selected based on the standard model fit parameters [31, 32]. Estimated means and 95% confidence limits were derived from GMM to describe fatigue trajectories for each group over time. T-tests and chi-square tests were used to assess differences between latent groups by demographic (age at diagnosis, sex, race/ethnicity), clinical (cancer stage, tumor site, treatment type), and behavioral characteristics (smoking, BMI). Stepwise multivariate logistic or multinomial regression analysis was conducted to identify significant fatigue-related risk factors by fitting a model with lowest AIC where all predictors are statistically significant (ps < 0.05). To examine selection bias, series of models were used to examine if attrition (those missing at least one timepoint) and missing data (those missing risk factors) was related to fatigue trajectories. All analyses were conducted in R version 4.1.2 (lcmm, lme4, or nnet packages) [33]. All tests were two-sided and significant if p < 0.05.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Participant characteristics are provided in Table 1. The mean age of participants at diagnosis was 61 years. Most participants were male (57%), non-Hispanic White (86%), and/or diagnosed with colon cancer (54%). Approximately half were diagnosed with advanced CRC (i.e., 36% stage III, 16% stage IV). Among all participants, 1,193 (74%) provided data at baseline, 925 (57%) at 3 months (M3), 830 (51%) at 6 months (M6), 723 (45%) at 12 months (M12), and 590 (37%) at 24 months (M24).

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics (N = 1,615)

| Overall (N = 1,615) |

Low Fatigue4 (n = 491) |

Moderate Fatigue (n = 545) |

High Fatigue (n = 579) |

P 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Age at diagnosis; M (SD) | 61.2 (12.7) | 60.2 (13.0) | 61.8 (12.3) | 61.4 (12.9) | 0.128 |

| Range | 19 – 92 | 19 – 90 | 25 – 92 | 21 – 91 | |

| Missing, n (%) | 10 (0.6) | 5 (1.0) | 4 (0.7) | 1 (0.1) | |

| Sex; n (%) | 0.002 | ||||

| Male | 921 (57.0) | 311 (63.3) | 303 (55.6) | 307 (53.0) | |

| Female | 694 (43.0) | 180 (36.7) | 242 (44.4) | 272 (47.0) | |

| Race/ethnicity; n (%) | 0.015 | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 1383 (85.6) | 402 (81.9) | 479 (87.9) | 502 (86.7) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 103 (6.4) | 44 (9.0) | 33 (6.1) | 26 (4.5) | |

| Hispanic | 64 (4.0) | 20 (4.1) | 14 (2.6) | 30 (5.2) | |

| Others1 | 49 (3.0) | 19 (3.9) | 12 (2.2) | 18 (3.1) | |

| Missing | 16 (1.0) | 6 (1.2) | 7 (1.3) | 3 (0.5) | |

| Stage at diagnosis; n (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| I | 293 (18.1) | 122 (24.8) | 101 (18.5) | 70 (12.1) | |

| II | 409 (25.3) | 136 (27.7) | 129 (23.7) | 144 (24.9) | |

| III | 582 (36.0) | 163 (33.2) | 200 (36.7) | 219 (37.8) | |

| IV | 258 (16.0) | 42 (8.6) | 86 (15.8) | 130 (22.5) | |

| Missing | 73 (4.5) | 28 (5.7) | 29 (5.3) | 16 (2.8) | |

| Tumor site; n (%) | 0.016 | ||||

| Colon | 875 (54.2) | 271 (55.2) | 305 (56.0) | 299 (51.6) | |

| Rectum | 679 (42.0) | 193 (39.3) | 219 (40.2) | 267 (46.1) | |

| Missing | 61 (3.8) | 27 (5.5) | 21 (3.9) | 13 (2.2) | |

| Adjuvant treatment; n (%) | 0.236 | ||||

| Yes | 829 (51.3) | 265 (54.0) | 285 (52.3) | 279 (48.2) | |

| No | 653 (40.4) | 187 (38.1) | 222 (40.7) | 244 (42.1) | |

| Missing | 133 (8.2) | 39 (7.9) | 38 (7.0) | 56 (9.7) | |

| Neoadjuvant treatment; n (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 993 (61.5) | 340 (69.2) | 333 (61.1) | 320 (55.3) | |

| No | 575 (35.6) | 133 (27.1) | 200 (36.7) | 242 (41.8) | |

| Missing | 47 (2.9) | 18 (3.7) | 12 (2.2) | 17 (2.9) | |

| Smoking status2 | <0.001 | ||||

| Never smoker | 742 (45.9) | 258 (52.5) | 248 (45.5) | 236 (40.8) | |

| Former smoker | 595 (36.8) | 167 (34.0) | 220 (40.4) | 208 (35.9) | |

| Current smoker | 201 (12.4) | 41 (8.4) | 52 (9.5) | 108 (18.7) | |

| Missing | 77 (4.8) | 25 (5.1) | 25 (4.6) | 27 (4.7) | |

| BMI3; M (SD) | 28.4 (6.3) | 28.1 (5.8) | 28.7 (6.4) | 28.4 (6.6) | 0.276 |

| Range | 12 – 66 | 15 – 66 | 12 – 65 | 13 – 66 | |

| Missing, n (%) | 47 (3.0) | 16 (3.4) | 22 (4.0) | 9 (1.6) | |

Notes:

Other includes Asians, Native Hawaiians, Native Americans, American Indian or Alaska Native, Pacific Islander, and patients reporting belonging to other or more than one race.

Never active smoker = people who have never smoked 100 cigarettes in their life. Former smoker = people who have smoked at least 100 cigarettes but stopped smoking for more than 2 years. Current smoker = people who currently smoke at least some days.

BMI = body mass index. Calculated using pounds and inches = (weight in pounds x 703) / (height in inches x height in inches).

The fatigue latent trajectory groups were generated from growth mixture models.

T-tests and chi-square tests were used to assess if demographic, clinical, and behavioral characteristics differed by latent group membership.

Fatigue Trajectories

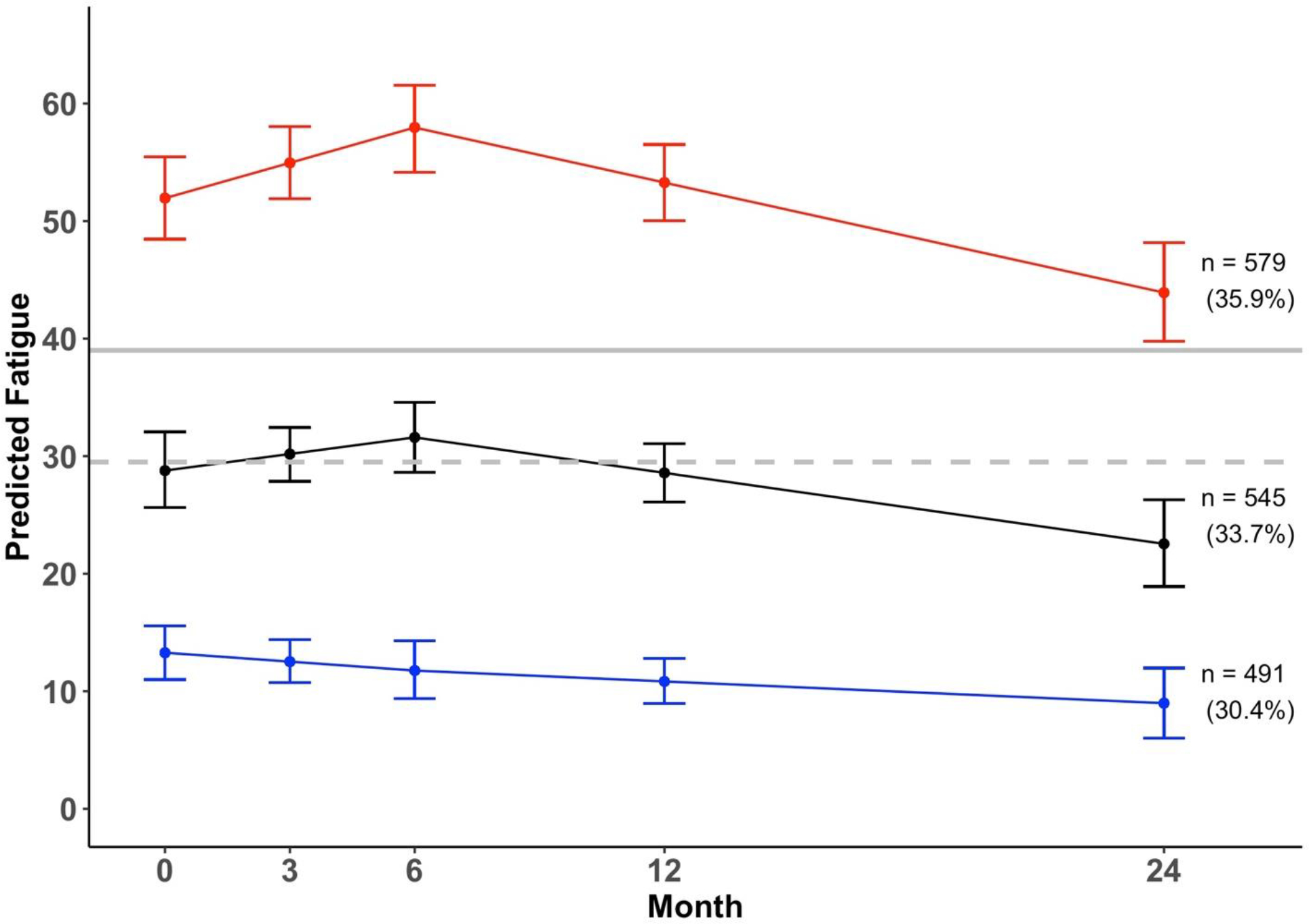

GMM model indices are presented in Table 2. The 3-class GMM model was selected because it had lowest AIC and BIC, indicating the best fit to the data [31, 32]. Estimated means for the high, moderate, and low fatigue groups are presented in Figure 1. The three groups had clinically meaningful differences in fatigue at baseline and throughout follow-up [29, 34].

Table 2.

Statistical fit indices of growth mixture models for different numbers of latent trajectories

| % Patients in each class |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classes | AIC | BIC | np | Δ-2LL | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|

| ||||||||

| 1 | 38931.8 | 38985.7 | 10 | - | 100 | - | - | - |

| 2 | 38697.3 | 38778.1 | 15 | 244.6*** | 61.4 | 38.6 | - | - |

| 3 | 38641.4 | 38749.1 | 20 | 65.9*** | 33.7 | 30.4 | 35.9 | - |

| 4 | 38649.4 | 38784.1 | 25 | 1.98 | 2.3 | 23.0 | 37.3 | 37.3 |

Note. AIC = Akaike information criterion, BIC = Bayesian information criterion; LL = log-likelihood; np = number of parameters.

p < .05

p < .01

p <.001

Figure 1.

Estimated trajectories of fatigue and 95% confidence intervals (n = 1,615).

Note. The red line represents high fatigue group, the black line represents the moderate fatigue group, the blue line represents low fatigue group, the dashed grey line represents the normative fatigue score (29.5), and the solid grey line represents the threshold for clinically meaningful fatigue (39) measured by EORTC-QLQ 30.

The high fatigue group (n = 579, 35.9%) reported clinically significant levels of fatigue on average [28] at baseline (estimated mean [M] = 51.9, 95% confidence interval [CI] = [48.4–55.5]) and throughout the follow-up period. From baseline to M6, fatigue significantly worsened (regression coefficient [b] = 1.0, Wald test = 2.8, p = 0.005), but this change was not clinically significant (at M6: M = 58.0, 95% CI = 54.2–61.6) [34]. From M6 to M24, fatigue significantly improved (b = −0.78, Wald test = −4.09, p < 0.01), and this change was clinically significant (at M24: M = 43.9, 95% CI = 39.9–48.2) [29, 34]. Overall improvement in fatigue from baseline to M24 (i.e., 8 points) was statistically significant (p < 0.05) but not clinically significant [29, 34].

The moderate fatigue group (n = 545, 33.7%) reported fatigue levels that were similar to the population norm [27] at baseline (M = 28.8, 95% CI = [25.6–32.0]). Fatigue did not significantly change from baseline to M6 (b = 0.47, Wald test = 1.30, p = 0.19) but significantly decreased from M6 (M = 31.6, 95% CI = 28.6–34.5) to M24 (M = 22.5, 95% CI = 18.8–26.2; b = −0.50, Wald test = −2.24, p = 0.025). Change in fatigue from baseline to M24 (i.e., 6.3 points) was neither statistically nor clinically significant [29, 34].

The low fatigue group (n = 491, 30.4%) reported fatigue levels that were significantly below the population norm [27] at baseline (M = 13.3, 95% CI = [10.9–15.6]) and remained stable throughout the follow-up period. Fatigue did not change from baseline to M6 (b = −0.25, Wald test = −1.0, p = 0.32) nor from M6 (M = 11.8, 95% CI = 9.5–14.2) to M24 (M = 9.0, 95% CI = 6.2–11.8; b = −0.15, Wald test = 0.31, p = 0.76). The overall change in fatigue from baseline to M24 (i.e., 4.3 points) was neither statistically nor clinically significant [29, 34].

Risk Factors for High Fatigue Group

In univariate analyses, patients’ sex, race/ethnicity, stage at diagnosis, tumor site, history of neoadjuvant treatment, and smoking status were associated with fatigue trajectory membership (ps ≤ 0.02), while age at diagnosis, history of adjuvant treatment, and BMI were not associated (ps ≥ 0.10) (Table 1). Multinomial logistic regression models were fitted using the moderate fatigue group as the reference group. Results of the forward stepwise multinomial logistic regression models (Table 3) indicated that compared to patients with moderate fatigue, those with low and stable fatigue trajectories were more likely to be male, Black, never smokers, have been diagnosed with less advanced cancer, and have lower BMI (ps < 0.05). On the other hand, compared to those who had moderate fatigue levels, high fatigue patients were more likely to have a higher stage of cancer (vs. stage I) and be current smokers (ps < 0.05). Age at diagnosis, cancer site, and receipt of adjuvant or neoadjuvant therapy were not associated with fatigue trajectories in multivariate analyses (ps >0.05).

Table 3.

Results from multinomial logistic regression models that examine if risk factors were related to latent trajectories of fatigue (n = 1,337).

| Low-stable vs Moderate Fatigue |

High-decreasing vs Morderate Fatigue |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | ||

|

| |||

| Age at diagnosis | 1 (0.98, 1.00) | 1 (1.00, 1.02) | |

| Female vs. Male | 0.6 (0.45, 0.80) *** | 1.2 (0.90, 1.55) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black vs. Non-Hispanic White | 2.1 (1.22, 3.56) ** | 0.7 (0.39, 1.30) | |

| Hispanic vs. Non-Hispanic White | 1.6 (0.72, 3.60) | 2.1 (0.98, 4.35) | |

| Others vs. Non-Hispanic White | 1.7 (0.73, 4.11) | 1.8 (0.78, 4.23) | |

| Stage II vs. I | 1.0 (0.64, 1.39) | 1.8 (1.18, 2.75) ** | |

| Stage III vs. I | 0.7 (0.45, 0.97) * | 1.7 (1.10, 2.51) * | |

| Stage IV vs. I | 0.4 (0.22, 0.63) *** | 2.5 (1.54, 3.98) *** | |

| Neoadjuvant treatment vs. No treatment before surgery | 0.8 (0.56, 1.05) | 1.2 (0.89, 1.59) | |

| Former vs. Never smoker | 0.7 (0.54, 0.99) * | 1 (0.78, 1.39) | |

| Current vs. Never smoker | 0.6 (0.37, 0.99) * | 2.4 (1.56, 3.55) *** | |

| BMI | 1 (0.95, 1.00) * | 1 (0.98, 1.02) | |

Note.

p < .05

p < .01

p <.001. The reference groups for categorical risk factors were male, non-Hispanic White, never smokers, patients with very early-stage disease (stage I), colon cancer, and no treatment.

Sensitivity Analysis

Regarding attrition, fatigue level and trajectories did not differ between patients who completed all possible surveys (n = 302) and those who missed at least one survey (n = 1,313) (ps > 0.10), which implies that missing data on the outcome variable (fatigue) are missing at random. Further, fatigue trajectories did not differ between patients who reported data for all risk factors (n = 1,337) and those who were missing data for at least one risk factor (n = 278) (ps > 0.50). Patients who did not have data for cancer stage (n = 73), disease site (n = 61), or BMI (n = 47) were more likely to belong to the low or moderate fatigue groups (ps < 0.01) than the high fatigue group. Individually missing other demographic, behavioral, or clinical characteristics was not related to fatigue level (ps > 0.05).

Discussion and Conclusions

The present study identified trajectories of fatigue among CRC patients in the two years after diagnosis and evaluated demographic, clinical, and behavioral risk factors for high fatigue. Three distinct trajectories in the two years after diagnosis were identified: high (36%), moderate (34%), and low fatigue (30%). The percentage of CRC patients with high fatigue is greater than the prevalence of fatigue among the general population (22%) and among patients with other common types of cancer [35, 36]. Patients were more likely to have high fatigue than moderate fatigue trajectories if they have more advanced cancer stage and report current smoking. We also found that being male, black, a non-smoker, having stage I or II disease or lower BMI may protect CRC patients from experiencing fatigue across time.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine latent trajectories of fatigue in a large, international, multisite sample of multi-stage (stage I-IV) CRC patients. Previous longitudinal studies with CRC patients showed that fatigue levels remained stable or decreased over time [15, 16]. Although it can be useful to describe the overall trajectory of fatigue, averaging across an entire sample may obscure the presence of subgroups with different baseline fatigue levels and different changes in fatigue. Therefore, it is important to examine the varied trajectories of fatigue and what factors contribute to these trajectories. Two European studies identified latent trajectories of fatigue among CRC patients. One study examined fatigue among 183 CRC patients from diagnosis to 18 months later and identified four trajectories including persistent severe fatigue (25.4%), moderate fatigue (56.1%), no fatigue (13.8%), and rapidly improving fatigue (4.7%) [37]. The other study followed 169 metastatic CRC patients undergoing chemotherapy for 6 months and classified four trajectories including intense fatigue (6.5%), moderate fatigue (48.5%), no fatigue (33%), and increasing fatigue (11.8%) [38]. Our study contributes to this literature by using data from a multi-site, international collaboration with a sample almost 10 times as large as past studies (n = 1,615), multi-stage CRC patients, and a longer follow-up period (up to 24 months post-diagnosis).

Our findings on fatigue risk factors among CRC patients were generally consistent with existing evidence for other common cancer types [39, 40]. However, age at diagnosis was not associated with higher fatigue, in contrast with the general cancer fatigue research demonstrating that older patients are less likely to report fatigue [41]. Previous studies have suggested that symptom clusters associated with fatigue in patients with CRC are independent of age [42]. Additional research is needed to understand the age-specific trajectories of fatigue among patients with CRC. Moreover, although cancer stage was a risk factor, cancer site and treatment were not associated with fatigue trajectories in our study in comparison with previous studies showing that types of neoadjuvant regimen were associated with worsening QoL [2]. It is possible that patients with early-stage CRC are more likely to have localized tumors amenable to surgical resection, without the need for additional adjuvant treatment. Those presenting with metastasis may experience greater treatment-related symptom burden owing to more extensive surgery, changes in bowel function, and adjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy related side effects [12]. Our findings about smoking status and BMI have implications for developing effective treatment of fatigue in cancer patients. Although it is commonly suggested that patients should be counseled on maintaining a healthy bodyweight, being physically active, eating a healthy diet, and smoking cessation, most of the CRC practice guidelines state that their recommendations are based on limited evidence. Our results provided important evidence for the clinical guidelines for supportive care oncology.

Major strengths of our study include the long-term follow-up period, large sample size, and inclusion of CRC patients diagnosed at all stages of disease. Compared to other studies among CRC, our study population consisted of a higher proportion of rectal (42%) cancers (versus 29% nationally), making the ColoCare Study cohort a rare resource to study this high-risk subgroup. Methodologically, we used the well-validated EORTC QLQ-C30 to measure fatigue consistently across different sites. Although we have high attrition rates at the 12-month and 24-month follow-ups, the GMM modeling used all available data over time to avoid nonresponse bias.

Study limitations should also be noted. We used a unidimensional scale to assess fatigue and relied on patients’ self-reporting, which may introduce subjective biases and variations in responses. Some of the clinical records and characteristics such as detailed data regarding co-morbidities, recurrence, and treatment regimens and dates were not available, precluding more specific analyses of fatigue in relation to treatment. Given the emerging treatment strategies for CRC in the past 5 years, more research is needed to examine duration of different treatments as risk factors for trajectories of fatigue among patients with CRC. Like other longitudinal observational studies in cancer patients, we have high attrition rates at the long-term follow ups. The study included few racial/ethnic minorities, in part because the eligible patients treated at the participating sites included few racial/ethnic minorities. Due to the limited measure of behavioral factors, we only examined smoking behavior in this current study. More research is needed to examine the prolonged impact of other behavioral factors (e.g., diet, sleep, physical activity) on change in fatigue and to include psychological predictors (such as depression and coping skills) [6, 38] as risk factors for fatigue trajectories among patients with CRC.

In conclusion, findings from the current study suggest that 36% of patients report high fatigue at CRC diagnosis and across the cancer trajectory. Patients who are diagnosed with more advanced stage, former or current smokers are more likely to have high/sustained fatigue than moderate fatigue trajectories. Supportive care interventions should be considered for these patients, particularly early in the cancer trajectory when they may have the most sustained impact. Drugs such as methylphenidate [43, 44] and interventions such as cognitive-behavioral therapy [45, 46] has been shown to improve fatigue in cancer patients and survivors and help them achieve the best possible quality of life after CRC diagnosis. Early implementation of evidence-based fatigue management strategies and care options will benefit patients during and after cancer therapy [47–50]. Our findings, along with the existing evidence [8, 37, 51], are in accordance with guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network that call for initiating early screening for fatigue and continual monitoring of fatigue until treatment completion.

What does this paper add to the literature?

Cancer-related fatigue is common among cancer patients but understudied among those with colorectal cancer (CRC). This study describes trajectories and risk factors of fatigue in 1,615 CRC patients. Findings have implications for clinical practice on cancer-related fatigue and other chronic symptoms that may impact quality of life post CRC diagnosis.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all ColoCare Study participants and the ColoCare Study team at multiple locations.

Financial Support

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Nursing Research R01NR018762 (PIs: Figueiredo, Jim). ColoCare Study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (U01 CA206110, R01 CA189184, R01 CA207371, R01 CA211705, R01 CA254108, R03CA270473, T32 HG008962, KL2TR00–2539), Stiftung LebensBlicke, German Consortium of Translational Cancer Research, (DKTK), German Cancer Research Center, Matthias Lackas Stiftung, Claussen-Simon Stiftung, Huntsman Cancer Foundation, Immunology, Inflammation, and Infectious Disease Initiative, and Cancer Control and Population Health Sciences (CCPS) at the University of Utah. This work was also supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute T32CA009168 (PIs: Etzioni, Schwartz), R2 U01 CA206110 (MPIs: Ulrich/ Siegel/ Li/ Toriola/ Figueiredo/ Shibata), 1A1 R01 CA189184 (PI: Li, Ulrich) and R01 CA207371 (PI: Ulrich, Li). This research was made possible through the Total Cancer Care Protocol at the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute and by the Tissue Core, PRISM and Molecular Genomics Core Facilities at the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute; an NCI designated Comprehensive Cancer Center (P30-CA076292).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

H.S.L.J. reports consulting to SBR Bioscience and grant funding from Kite Pharma. B.D.G reports fees unrelated to this work from Sure Med Compliance and Elly Health. K.M. reports consultant to Reimagine Care. All other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Han CJ, Yang GS, Syrjala K. Symptom experiences in colorectal cancer survivors after cancer treatments: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Nurs. 2020;43(3):E132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Couwenberg AM, Burbach JPM, van Grevenstein WMU, Smits AB, Consten ECJ, Schiphorst AHW, et al. Effect of Neoadjuvant Therapy and Rectal Surgery on Health-related Quality of Life in Patients With Rectal Cancer During the First 2 Years After Diagnosis. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2018;17(3):e499–e512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shi Q, Smith TG, Michonski JD, Stein KD, Kaw C, Cleeland CS. Symptom burden in cancer survivors 1 year after diagnosis: a report from the American Cancer Society’s Studies of Cancer Survivors. Cancer. 2011;117(12):2779–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu HS, Harden JK. Symptom burden and quality of life in survivorship: a review of the literature. Cancer Nurs. 2015;38(1):E29–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hofman M, Ryan JL, Figueroa-Moseley CD, Jean-Pierre P, Morrow GR. Cancer-related fatigue: the scale of the problem. Oncologist. 2007;12 Suppl 1:4–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oh PJ, Cho JR . Changes in Fatigue, Psychological Distress, and Quality of Life After Chemotherapy in Women with Breast Cancer: A Prospective Study. Cancer Nurs. 2020;43(1):E54–E60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller M, Maguire R, Kearney N. Patterns of fatigue during a course of chemotherapy: results from a multi-centre study. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2007;11(2):126–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xian X, Zhu C, Chen Y, Huang B, Xu D. A longitudinal analysis of fatigue in colorectal cancer patients during chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29(9):5245–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lawrence DP, Kupelnick B, Miller K, Devine D, Lau J. Evidence report on the occurrence, assessment, and treatment of fatigue in cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2004(32):40–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aouizerat BE, Dhruva A, Paul SM, Cooper BA, Kober KM, Miaskowski C. Phenotypic and Molecular Evidence Suggests That Decrements in Morning and Evening Energy Are Distinct but Related Symptoms. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;50(5):599–614 e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goedendorp MM, Andrykowski MA, Donovan KA, Jim HS, Phillips KM, Small BJ, et al. Prolonged impact of chemotherapy on fatigue in breast cancer survivors: a longitudinal comparison with radiotherapy-treated breast cancer survivors and noncancer controls. Cancer. 2012;118(15):3833–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rutherford C, Campbell R, White K, King M. Patient-reported outcomes as predictors of survival in patients with bowel cancer: a systematic review. Qual Life Res. 2019;28(11):2871–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mota DD, Pimenta CA, Caponero R. Fatigue in colorectal cancer patients: prevalence and associated factors. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2012;20(3):495–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vardy J, Dhillon HM, Pond GR, Rourke SB, Xu W, Dodd A, et al. Cognitive function and fatigue after diagnosis of colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol. 2014;25(12):2404–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vardy JL, Dhillon HM, Pond GR, Renton C, Dodd A, Zhang H, et al. Fatigue in people with localized colorectal cancer who do and do not receive chemotherapy: a longitudinal prospective study. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(9):1761–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Husson O, Mols F, van de Poll-Franse LV, Thong MS. The course of fatigue and its correlates in colorectal cancer survivors: a prospective cohort study of the PROFILES registry. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23(11):3361–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li SX, Liu BB, Lu JH. Longitudinal study of cancer-related fatigue in patients with colorectal cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15(7):3029–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ulrich CM, Gigic B, Bohm J, Ose J, Viskochil R, Schneider M, et al. The ColoCare Study: A Paradigm of Transdisciplinary Science in Colorectal Cancer Outcomes. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2019;28(3):591–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gigic B, Boeing H, Toth R, Bohm J, Habermann N, Scherer D, et al. Associations Between Dietary Patterns and Longitudinal Quality of Life Changes in Colorectal Cancer Patients: The ColoCare Study. Nutr Cancer. 2018;70(1):51–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gigic B, Nattenmuller J, Schneider M, Kulu Y, Syrjala KL, Bohm J, et al. The Role of CT-Quantified Body Composition on Longitudinal Health-Related Quality of Life in Colorectal Cancer Patients: The Colocare Study. Nutrients. 2020;12(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Himbert C, Ose J, Lin T, Warby CA, Gigic B, Steindorf K, et al. Inflammation- and angiogenesis-related biomarkers are correlated with cancer-related fatigue in colorectal cancer patients: Results from the ColoCare Study. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2019;28(4):e13055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ose J, Gigic B, Lin T, Liesenfeld DB, Bohm J, Nattenmuller J, et al. Multiplatform Urinary Metabolomics Profiling to Discriminate Cachectic from Non-Cachectic Colorectal Cancer Patients: Pilot Results from the ColoCare Study. Metabolites. 2019;9(9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1993;85(5):365–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Minton O, Stone P. A systematic review of the scales used for the measurement of cancer-related fatigue (CRF). Ann Oncol. 2009;20(1):17–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knobel H, Loge JH, Brenne E, Fayers P, Hjermstad MJ, Kaasa S. The validity of EORTC QLQ-C30 fatigue scale in advanced cancer patients and cancer survivors. Palliat Med. 2003;17(8):664–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fayers P, Aaronson NK, Bjordal K, Groenvold M, Curran D, A B, et al. EORTC QLQ–C30 scoring manual. 3rd ed. Brussels, Belgium: European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nolte S, Liegl G, Petersen MA, Aaronson NK, Costantini A, Fayers PM, et al. General population normative data for the EORTC QLQ-C30 health-related quality of life questionnaire based on 15,386 persons across 13 European countries, Canada and the Unites States. Eur J Cancer. 2019;107:153–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Giesinger JM, Kuijpers W, Young T, Tomaszewski KA, Friend E, Zabernigg A, et al. Thresholds for clinical importance for four key domains of the EORTC QLQ-C30: physical functioning, emotional functioning, fatigue and pain. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2016;14:87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cocks K, King MT, Velikova G, Fayers PM, Brown JM. Quality, interpretation and presentation of European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer quality of life questionnaire core 30 data in randomised controlled trials. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44(13):1793–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ram N, Grimm KJ. Growth Mixture Modeling: A Method for Identifying Differences in Longitudinal Change Among Unobserved Groups. Int J Behav Dev. 2009;33(6):565–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bertoletti M, Friel N, Rastelli R. Choosing the number of clusters in a finite mixture model using an exact integrated completed likelihood criterion. Metron. 2015;73(2):177–99. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Diallo TM, Morin AJ, Lu H. Performance of growth mixture models in the presence of time-varying covariates. Behav Res Methods. 2017;49(5):1951–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing.. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Musoro JZ, Sodergren SC, Coens C, Pochesci A, Terada M, King MT, et al. Minimally important differences for interpreting the EORTC QLQ-C30 in patients with advanced colorectal cancer treated with chemotherapy. Colorectal Dis. 2020;22(12):2278–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Al Maqbali M, Al Sinani M, Al Naamani Z, Al Badi K, Tanash MI. Prevalence of Fatigue in Patients With Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2021;61(1):167–89 e14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Galland-Decker C, Marques-Vidal P, Vollenweider P. Prevalence and factors associated with fatigue in the Lausanne middle-aged population: a population-based, cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open. 2019;9(8):e027070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Müller F, Tuinman MA, Janse M, Almansa J, Sprangers MA, Smink A, et al. Clinically distinct trajectories of fatigue and their longitudinal relationship with the disturbance of personal goals following a cancer diagnosis. Br J Health Psychol. 2017;22(3):627–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baussard L, Proust-Lima C, Philipps V, Portales F, Ychou M, Mazard T, et al. Determinants of Distinct Trajectories of Fatigue in Patients Undergoing Chemotherapy for a Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: 6-Month Follow-up Using Growth Mixture Modeling. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2022;63(1):140–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Adam S, van de Poll-Franse LV, Mols F, Ezendam NPM, de Hingh I, Arndt V, et al. The association of cancer-related fatigue with all-cause mortality of colorectal and endometrial cancer survivors: Results from the population-based PROFILES registry. Cancer Med. 2019;8(6):3227–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huang X, Zhang Q, Kang X, Song Y, Zhao W. Factors associated with cancer-related fatigue in breast cancer patients undergoing endocrine therapy in an urban setting: a cross-sectional study. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saligan LN, Olson K, Filler K, Larkin D, Cramp F, Yennurajalingam S, et al. The biology of cancer-related fatigue: a review of the literature. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23(8):2461–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Agasi-Idenburg SC, Thong MS, Punt CJ, Stuiver MM, Aaronson NK. Comparison of symptom clusters associated with fatigue in older and younger survivors of colorectal cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25(2):625–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Qu D, Zhang Z, Yu X, Zhao J, Qiu F, Huang J. Psychotropic drugs for the management of cancer-related fatigue: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2016;25(6):970–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Correa-Morales JE, Cuellar-Valencia L, Mantilla-Manosalva N, Quintero-Munoz E, Iriarte-Aristizabal MF, Giraldo-Moreno S, et al. Cancer and Non-cancer Fatigue Treated With Bupropion: A Systematic Review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2023;65(1):e21–e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jim HSL, Hyland KA, Nelson AM, Pinilla-Ibarz J, Sweet K, Gielissen M, et al. Internet-assisted cognitive behavioral intervention for targeted therapy-related fatigue in chronic myeloid leukemia: Results from a pilot randomized trial. Cancer. 2020;126(1):174–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Van Gessel LD, Abrahams HJG, Prinsen H, Bleijenberg G, Heins M, Twisk J, et al. Are the effects of cognitive behavior therapy for severe fatigue in cancer survivors sustained up to 14 years after therapy? J Cancer Surviv. 2018;12(4):519–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dun L, Xian-Yi W, Si-Ting H. Effects of Cognitive Training and Social Support on Cancer-Related Fatigue and Quality of Life in Colorectal Cancer Survivors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Integr Cancer Ther. 2022;21:15347354221081271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xian X, Zhu C, Chen Y, Huang B, Xiang W. Effect of Solution-Focused Therapy on Cancer-Related Fatigue in Patients With Colorectal Cancer Undergoing Chemotherapy: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Cancer Nurs. 2022;45(3):E663–E73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sleight AG, Crowder SL, Skarbinski J, Coen P, Parker NH, Hoogland AI, et al. A New Approach to Understanding Cancer-Related Fatigue: Leveraging the 3P Model to Facilitate Risk Prediction and Clinical Care. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Aapro M, Scotte F, Bouillet T, Currow D, Vigano A. A Practical Approach to Fatigue Management in Colorectal Cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2017;16(4):275–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jim HS, Sutton SK, Jacobsen PB, Martin PJ, Flowers ME, Lee SJ. Risk factors for depression and fatigue among survivors of hematopoietic cell transplantation. Cancer. 2016;122(8):1290–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]