Abstract

Routine urine cultures were performed in cats with chronic kidney disease (CKD) to assess the overall prevalence and clinical signs associated with a positive urine culture (PUC). An occult urinary tract infection (UTI) was defined as a PUC not associated with clinical signs of lower urinary tract disease or pyelonephritis. Multivariate logistic and Cox proportional hazard regression models were used to evaluate the risk factors for an occult UTI and its relationship with survival. There were 31 PUCs from 25 cats. Eighty-seven percent of PUCs had active urine sediments. The most common infectious agent was Escherichia coli and most bacteria were sensitive to amoxicillin-clavulanate. Eighteen of 25 cats had occult UTIs. Among cats with occult UTI, increasing age in female cats was significantly associated with PUC; no significant association between occult UTI and survival was found and serum creatinine was predictive of survival in the short term (200 days) only. In conclusion, among cats with CKD, those with occult UTI were more likely to be older and female, but there was no association with severity of azotaemia. The presence of an occult UTI, when treated, did not influence survival.

Introduction

As a species, cats have traditionally been considered resistant to bacterial infection of the lower urinary tract with positive cultures present in 1% of healthy cats, and 1–3% of cats with clinical signs of lower urinary tract disease.1–3 In contrast, surveys of older cats with comorbidities, such as chronic kidney disease (CKD), diabetes mellitus and hyperthyroidism, have identified a substantially greater number of cats with bacterial urinary tract infection (UTI), with up to a third of some cohorts having positive urine cultures (PUCs).4–7

There are marked differences in the clinical signs demonstrated by cats with PUCs. Unlike the overt clinical signs (eg, haematuria, stranguria and pollakiuria) demonstrated by younger cats with lower urinary tract disease (LUTD) of all causes, PUC in older cats with concurrent diseases were frequently asymptomatic or occult.4,8

In general, older female cats are at increased risk for a PUC.4,9 Despite some differences in case selection and analytical methods, an increased risk of positive cultures in female cats has been a consistent finding of all studies to date.4,7,9,10 The risk associated with increasing age, however, has not been a consistent observation. Specifically, among older cats with concurrent disease, increasing age has not always been associated with increased risk of a PUC.7,8

One proposed mechanism for the association of age, comorbidities and PUCs is the reduction in urine concentrating ability observed in diseases commonly encountered in older cats. 11 Urine hypertonicity and the associated high concentration of intrinsic antimicrobial factors are considered part of the lower urinary tract’s normal defences against bacterial UTI. 12 However, no difference was identified in urine specific gravity (USG) between cats with and without a PUC. 4 In addition, in the only study to consider the confounding effect of concurrent disease, decreasing USG was not associated with a PUC. 10

Guidelines for the management of many feline geriatric diseases recommend routine urine cultures. 7 In cats with CKD, PUCs are common7,10,13 and treatment is generally recommended to reduce the risks of ascending infection exacerbating renal injury. Whether the presence of bacteria in the bladder is a marker for, or contributes to, increased severity of kidney disease is unknown. Interestingly, no association between serum creatinine concentration and a PUC has been found in studies of cats with CKD and diabetes mellitus.8,10 Treatment of PUCs in the absence of clinical signs is not without potential problems. Cost, difficulties in administrating the medication and poor compliance are all recognised issues in the use of antibiotics, especially in feline medicine. More importantly, the acquisition of antibiotic resistance has been demonstrated in dogs and cats with persistent UTI.14,15 Furthermore, UTI associated Escherichia coli can be transmitted between household members, including animals.16,17

In determining optimal treatment strategies, it might help to distinguish between cats with and without clinical signs of LUTD. In elderly women, UTI infections associated with clinical signs can result in hospitalisation, bacteraemia and death, 18 but treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria in elderly people has been shown to have no beneficial effect on survival, future symptomatic episodes or the prevalence of bacteriuria, and is no longer recommended. 19

The initial aim of this study was to define the prevalence and clinical signs associated with a PUC in a cohort of cats with CKD. Occult UTIs were defined as a positive culture in a cat without clinical signs of LUTD or pyelonephritis. Among cats with occult UTIs, the study further aimed to determine the risks factors for a PUC and investigate the association between a PUC and disease severity, assessed by creatinine concentration and survival.

Materials and methods

Study population

Cats were recruited from two veterinary hospitals, a primary accession inner-city clinic and a university veterinary teaching hospital (with both referral and primary accession patients) between 1 November 1999 and 31 December 2003 (inclusive). All cats with pre-existing or newly diagnosed CKD were eligible for inclusion. CKD was defined as consistent clinical signs with either (i) creatinine concentration >180 µmol/l with inappropriate urine concentration (USG ≤1.035), (ii) persistently increased serum creatinine concentrations without identifiable cause of pre-renal azotaemia, (iii) proteinuria of renal origin confirmed by a urine protein to creatinine ratio >1 or (iv) minimally concentrated urine (USG ≤1.035) on more than three occasions without another identifiable cause for polydipsia. CKD was categorised according to International Renal Interest Society (IRIS) guidelines. 20

With the owners’ consent, urine specimens for microbial culture were obtained by cystocentesis, regardless of the presence of absence of clinical signs of lower urinary tract disease. Urine culture results and clinical records were collated and reviewed by the first author. The follow-up period for survival analysis ended on 31 May 2009. Information regarding survival was obtained from each cat’s medical record or by contacting the owner at the end of the follow-up period.

Sample collection, processing and data collection

All urine specimens were collected aseptically by antepubic cystocentesis using standard technique. 21 Samples were either processed immediately or refrigerated briefly prior to submission to either the commercial diagnostic laboratory (Vetnostics), or the University of Sydney’s Veterinary Diagnostic Pathology Services for standard urinalysis and aerobic microbial culture. Urinalysis was performed using reagent strips (Multistix 10 SG; Bayer) to assess biochemical parameters, microscopic sediment examination to examine for cells and microorganisms, and a refractometer to assess USG. Samples were mixed well and examined macroscopically for colour, volume and turbidity. Using a calibrated loop, 1 μl of well-mixed urine was inoculated onto blood agar base number 2 supplemented with 5% sheep blood (SBA; Oxoid Australia) and spread for single colonies. Plates were incubated aerobically at 37°C for a maximum of 72 h, with assessment of the degree and purity of growth made at 24 h intervals, with all bacterial growth considered significant. A range of standard methods for phenotypic identification of isolates was used and commercial biochemical identification kits (Oxoid; Biomerieux). Antimicrobial susceptibility patterns for all isolates were determined by the Kirby–Bauer disc diffusion method for a range of antimicrobials according to the guidelines of the Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute. An active sediment was defined as pyuria [>five white blood cells/high power field (HPF)], haematuria (>five red blood cells/HPF) or bacteriuria.

Information regarding signalment, the date CKD was diagnosed, urine culture date(s), creatinine concentration, clinical signs, urinalysis and urine culture results was obtained from each cat’s medical records. Clinical signs consistent with lower urinary tract signs included stranguria, haematuria and pollakiuria. Pyelonephritis was suspected on the basis of clinical signs (abdominal pain, pyrexia, renomegaly) and haematological findings (neutrophilia with left shift).

Statistical analyses

Cats were classified as having a PUC if any urine specimen collected over the 3-year period was positive, even if the initial culture result was negative. Where multiple urine cultures were performed, the cat’s age and serum creatinine concentration were determined either at (i) the time of the first urine culture (if this, and subsequent, cultures were negative) or (ii) at the time of the first PUC. Where cats had multiple PUC results, information regarding age, creatinine and clinical signs was obtained from the first positive culture. Cats were only included in each analysis once, ie, with either a positive or negative culture result.

Further statistical analyses were performed to compare cats with occult UTIs to cats with negative urine cultures. Among cats with occult UTI, two outcomes were evaluated using regression analysis. A logistic regression analysis was performed to identify risk factors for a PUC and a Cox proportional hazard regression was used to quantify the association between a PUC and survival. Analyses accounted for the potentially confounding effect of age, sex (male or female), breed (pedigree or domestic), the laboratory at which the sample was cultured and disease severity (as assessed by creatinine concentration).

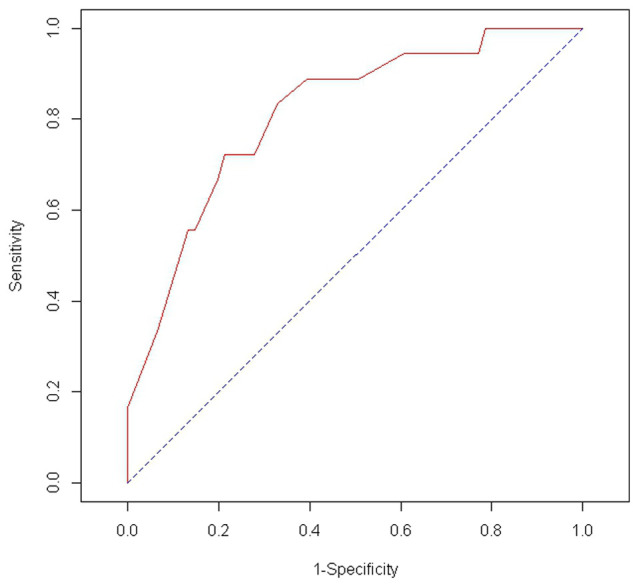

To select variables that best explained the probability of a cat being culture-positive, a backward stepwise approach was used. Variables associated with a cat being culture-positive at an α level <0.2 were entered into the model. The significance of each explanatory variable was tested using the Wald test. Biologically plausible, multiplicative two-way interactions between the remaining variables were assessed for significance. The results of the final model are reported in terms of adjusted odds ratios (OR) for each explanatory variable. The overall significance of the final model was assessed with the likelihood ratio test. A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was constructed on the basis of culture status predicted by the model to provide a measure of the model’s ability to discriminate between culture-positive and culture-negative cats.

Survival of cats with CKD was calculated from the date of the urine culture to the date of euthanasia or death from any other cause. Cats were right censored at date of last consultation if the date of euthanasia was unknown. Kaplan–Meier survival curves were calculated for cats grouped according to age ( ≤ or > median of 13 years), urine culture status (positive vs negative), breed, gender and disease stage (IRIS).22,23 Explanatory variables associated with survival at an α level of <0.2 using the log rank test were selected for inclusion in a Cox proportional hazards model. A backwards stepwise approach was used, as for the logistic regression analysis. The assumption of a linear relationship between serum creatinine and the logarithm of hazard was tested and confirmed using the Martingale residuals from the final Cox model. 24 The assumption of proportional hazards was assessed by plotting the Schoenfeld residuals as a function of time. 25 Significant correlation in the Schoenfeld residuals as a function of time indicated that the proportional hazards assumption was, in this case, violated. To account for this, survival time was categorised into two periods: <200 days after enrolment and >200 days after enrolment. The model was then re-parameterised to allow creatinine to be treated as a time-dependent variable, with two regression coefficients reported: the first quantifying the effect of creatinine concentration at enrolment on survival during the first 200 days of follow-up, and the second quantifying the effect of creatinine concentration at enrolment on survival after 200 days of follow-up.

Post hoc power analysis was performed to evaluate the ability of the study to detect a significant association between an occult UTI and survival at an α of 0.05.

Results

Urine culture results

Eighty-six cats (42 female, 44 male) with CKD had routine urine cultures performed [median age 13 years interquartile range (IQR) 10–15 years]. Two, 26, 41 and 17 cats had IRIS stage 1, 2, 3 and 4 CKD, respectively, when urine cultures were performed. All cats except one male were neutered. Thirty-three cats had two urine cultures, 12 cats had a third culture and five cats had four urine cultures during the study period. In total, 134 urine cultures were performed, excluding intra- and post-treatment cultures, of which 31 were positive from 25 cats (19 female and six male). In four female cats initial urine cultures were negative, but subsequent urine cultures were positive, and these cats were classified as positive for analytical purposes.

Of the 25 cats with positive cultures, 18 showed no clinical signs of a UTI. Only two cats were described by the owners as having signs consistent with LUTD, while pyelonephritis was suspected in five cats. Five cats had two or more PUCs. In these cats, clinical signs reported by the owners varied between episodes. These five cats were female, with a median age of 16 years. Repeat urine cultures were associated with the same bacterial species on three occasions (E coli) and different species on two occasions (E coli and Klebsiella species followed by β-haemolytic Group G species;Enterococcus species followed by E coli).

An active sediment was present in 27/31 (87%) positive cultures. Overall, 27/31 positive cultures (87%) involved a single organism, while 4/31 positive cultures involved concurrent growth of two organisms. Escherichia coli were the most common infectious agent cultured, present in 22/31 (71%) PUCs. Five urine cultures were positive only for β-haemolytic Group G species; Other microorganisms identified included Enterobacter cloacae (one), Enterococcus species (two) and Klebsiella pnemoniae (one). Urine culture from one cat was positive for Cryptococcus neoformans var grubii.

The majority of bacteria identified were susceptible to amoxicillin (23/34; 68% antibiograms) and amoxicillin-clavulanate (29/34; 85% antibiograms). Escherichia coli was the most common bacterial isolate from cats with clinical signs suggestive of pyelonephritis (4/5, the remaining cat had a β-haemolytic Streptococcus group G infection); all bacterial species isolated from these cats were susceptible to amoxicillin-clavulanate.

Multivariate analyses

Seventy nine cats were evaluated statistically, including 18 cats with occult UTIs and 61 cats with negative urine cultures (Table 1). Bivariate results are displayed in Table 2. In the multivariate model, only the interaction of age and sex was a significant risk factor for a PUC [OR = 2.0, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.1-4.9, P = 0.048]. Among cats with CKD, the risk of an occult PUC increased twofold for each year increase-in-age among female cats. The area under the ROC curve was 0.81, indicating that the model had good discriminatory ability (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Chronic kidney disease and urine culture results from in 79 cats: descriptive statistics stratified by urine culture status. Seventy-nine cats were evaluated statistically, including 18 cats with occult UTIs and 61 cats with negative urine cultures

| Variable | Urine culture results |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | Positive | All | |

| Age (years): | |||

| Mean (SD) | 15.0 (3.7) | 14.8 (2.9) | 12.4 |

| Median (Q1–Q3) | 12.0 (10.0–15.0) | 15.0 (14.3–16.0) | 13.0 (10.0–15.0) |

| Minimum, maximum | 2.0, 20.0 | 6.0, 18.0 | 2.0, 20.0 |

| IRIS stage (number of cats): | |||

| Stage 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 2 | 19 | 7 | 26 |

| 3 | 26 | 9 | 35 |

| 4 | 15 | 1 | 16 |

| Sex (number of cats) | |||

| Male:female | 38:23 | 6:12 | 44:35 |

IRIS = International Renal Interest Society; Q1, Q3 = first and third quartiles

Table 2.

Risk factors for an occult urine culture in 79 cats with chronic kidney disease (CKD) * . Regression coefficients and standard errors from bivariate logistic regression †

| Variable | Coefficient (SE) | P | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 1.19 (0.57) | 0.035 | 3.30 (1.12–10.64) |

| Age | 0.31 (0.11) | 0.004 | 1.37 (1.13–1.74) |

| Breed | 0.82 (0.62) | 0.19 | 2.27 (0.72–8.75) |

| Creatinine | −0.002 (0.002) | 0.19 | 0.99 (0.99–1.00) |

| Laboratory | −0.05 (0.55) | 0.93 | 0.95 (0.33–2.91) |

Associated clinical signs refers to clinical signs consistent with lower urinary tract disease and pyelonephritis. All cats had clinical signs consistent with CKD and some had clinical signs associated with concurrent, unrelated disease

In the multivariate model only the interaction of age and gender was a significant risk factor for a positive urine culture [coefficient = 0.75, SE = 0.36, P = 0.038, OR and 95% CI = 2.13 (1.2–5.1)]. Among cats with CKD, the risk of an occult urinary tract infection increased twofold for each 1 year increase in age among female cats

CI = confidence interval; CKD = chronic kidney disease; OR = odds ratio; SE = standard error

Figure 1.

Receiver operator characteristic curve describing the predictive ability of the multivariate model for occult urinary tract infection in cats with chronic kidney disease

Creatinine concentration at the time of enrolment was the only variable significantly associated with survival in the final Cox proportional hazards model. Creatinine concentration was significantly associated with survival only for the first 200 days after enrolment into the study. Each 10 μmol increase in creatinine concentration was associated with a 3% increase in the daily hazard of death (Table 3).

Table 3.

Chronic kidney disease and occult urinary tract infection (UTI) in 79 cats. Regression coefficients and standard errors from a Cox proportional hazards regression model identifying risk factors for survival

| Variable | Cats (n) | Deaths (n) | Coefficient (SE) * | P | Hazard ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Creatinine concentration: | |||||

| ≤ 200 days † | 79 | 31 | 0.003 (0.0005) | <0.00 | 1.003 (1.002–1.004) |

| > 200 days | 37 | 32 | −0.0009 (0.001) | −0.38 | 0.999 (0.997–1.001) |

≤200 days after enrolment into the study

Interpretation: 79 cats includes 18 cats with occult UTIs and 61 cats with negative urine cultures. At the end of 200 days, 31 cats had died, 37 cats survived and entered the second component to the survival analysis, and 11 cats were censored. Each 10 μmol/l increase in creatinine concentration was associated with a 1.03 (1.02–1.04) increase in the daily hazard of death for the first 200 days after testing

CI = confidence interval; SE = standard error

Post hoc power analysis revealed that the survival analysis had a 79% chance of detecting a significant difference in survival between occult PUC and urine culture negative cats (α = 0.05).

Discussion

Thirty percent of cats with CKD had a PUC at some stage during the study period and the majority of positive cultures were occult. The most frequently cultured pathogen was E coli. Increasing age was significantly associated with an increased risk of an occult UTI among female cats, an association not present in male cats. These observations concur with previous work on cats with and without clinical signs of a UTI.7,10

There was no association between occult PUC and disease severity or survival. While this might be the result of effective treatment of the infection, several observations make this unlikely. Recurrent infections were common in this and previous studies of cats with CKD, as they are in women with bacteriuria.15,26,27 Treatment of a single episode did not prevent further positive cultures in many cats nor did treatment of occult UTI prevent the development of future episodes of LUTD or pyelonephritis. Therefore, it seems unlikely that treatment of a single PUC prevented relapse or re-infection and, therefore, likely that at least some cats had undetected episodes of bacteriuria over the study period.

The number of cats presumptively diagnosed with pyelonephritis was unexpected and might have been over-estimated. Confirmation of an ascending infection, if not renal parenchymal involvement, could be achieved in the future by sonographically-guided aspirates and subsequent culture of urine from the renal pelvis, but this would be technically demanding in some instances. An issue that remains unaddressed in studies of feline CKD is the significance of bacteria in the lower urinary tract in terms of contribution to disease progression. Potentially, cats with CKD have a range of structural and functional abnormalities that predispose them to pyelonephritis. Furthermore, compared with normal cats, they are less able to cope with even minimal damage to remaining nephrons. Conversely, the polyuria of CKD reduces renal medullary hypertonicity, which could help protect against renal infection by facilitating the migration of inflammatory cells. 28 It would be advantageous to improve our identification of host characteristics and pathogen virulence factors that determine an individual cat’s susceptibility to pyelonephritis.

It is likely that female cats with CKD are at greater risk of bacteriuria than male cats owing to anatomical features, such as shorter urethral length, although the exact reason for a female cat’s susceptibility to UTIs remains unproven. 28 While virulence factors of uropathogenic E coli in dogs and cats have been described, the identification of E coli isolates with no detectable urovirulence factors in dogs with multiple UTI emphasises the importance of reduced host resistance mechanisms.14,29

Creatinine concentration was significantly associated with survival for the first 200 days after enrolment. A single creatinine determination did not have a significant influence on long-term survival, presumably as disease progression and concurrent disease become more important. The prognostic value of multiple variables has been evaluated in cats with CKD. Of those assessed, creatinine concentration, often categorised according to IRIS guidelines, has usually,22,23 but not invariably, 30 been associated with survival. Changes in creatinine concentration over time might be a better predictor of long-term survival, as has been suggested in dogs with CKD. 31

This study had several limitations. Treatment and timing of repeat urine cultures were at the discretion of attending veterinarian and owners. The lack of a structured plan for repeat urine cultures on all cats, but especially on those with negative urine cultures, means a substantial number of occult UTIs may have been missed. As the majority of cats with CKD and PUCs have occult UTIs further studies into bacteriuria and CKD should involve systematic and repeated urine cultures of all enrolled cats over time.

The inherent variability in these data makes it impossible to comment on the efficacy of treatment other than the subjective observation that recurrence or persistence of infection appeared to be common. Similar observations have been made by other groups,15,26 and this subject requires further study. A randomised clinical trial would be the ideal way to determine the optimal treatment of occult UTI in cats with and without concurrent disease.

Conclusions

The identification of occult UTIs in many cats, especially those with concurrent disease in this and previous studies, 4 and the lack of any association between the presence of occult UTIs, disease severity and survival suggests more investigation into the optimal treatment of occult UTI in cats is required.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the microbiological assistance of Patricia Martin, Faculty of Veterinary Science, University of Sydney.

Footnotes

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

The authors do not have any potential conflicts of interest to declare.

Accepted: 6 November 2012

References

- 1. Kruger JM, Osborne CA, Goyal SM, et al. Clinical evaluation of cats with lower urinary-tract disease. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1991; 199: 211–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Buffington CA, Chew DJ, Kendall MS, et al. Clinical evaluation of cats with non-obstructive urinary tract diseases. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1997; 210: 46–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lees GE. Bacterial urinary tract infections. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 1996; 26: 297–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Litster A, Moss S, Platell J, Trott DJ. Occult bacterial lower urinary tract infections in cats – urinalysis and culture findings. Vet Microbiol 2009; 136: 130–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Eggertsdottir AV, Lund HS, Krontveit R, Sorum H. Bacteria in cats with feline lower urinary tract disease: a clinical study of 134 cases Norway. J Feline Med Surg 2007; 9: 458–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gerber B, Boretti FS, Kley S, et al. Evaluation of clinical signs and causes of lower urinary tract disease in European cats. J Small Anim Pract 2005; 46: 571–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mayer-Roenne B, Goldstein RE, Erb HN. Urinary tract infections in cats with hyperthyroidism, diabetes mellitus and chronic kidney disease. J Feline Med Surg 2007; 9: 124–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bailiff NL, Nelson RW, Feldman EC, et al. Frequency and risk factors for urinary tract infection in cats with diabetes mellitus. J Vet Intern Med 2006; 20: 850–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lekcharoensuk C, Osborne CA, Lulich JP. Epidemiologic study of risk factors for lower urinary tract diseases in cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2001; 218: 1429–1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bailiff NL, Westropp JL, Nelson RW, et al. Evaluation of urine specific gravity and urine sediment as risk factors for urinary tract infections in cats. Vet Clin Pathol 2008; 37: 317–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bartges JW, Barsanti JA. Bacterial urinary tract infection in cats. In: Bonagura J. (ed). Kirk’s current veterinary therapy XIII: small animal practice. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Company, 2000, pp 880–882. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Litster A, Thompson M, Moss S, Trott D. Feline bacterial urinary tract infections: An update on an evolving clinical problem. Vet J 2011; 187: 18–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. DiBartola SP, Rutgers HC, Zack PM, Tarr MJ. Clinicopathologic findings associated with chronic renal disease in cats: 74 cases (1973–1984). J Am Vet Med Assoc 1987; 190: 1196–1202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Drazenovich N, Ling GV, Foley J. Molecular investigation of Escherichia coli strains associated with apparently persistent urinary tract infection in dogs. J Vet Intern Med 2004; 18: 301–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Freitag T, Squires RA, Schmid J, et al. Antibiotic sensitivity profiles do not reliably distinguish relapsing or persisting infections from reinfections in cats with chronic renal failure and multiple diagnoses of Escherichia coli urinary tract infection. J Vet Intern Med 2006; 20: 245–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Johnson JR, Owens K, Gajewski A, Clabots C. Escherichia coli colonization patterns among human household members and pets, with attention to acute urinary tract infection. J Infect Dis 2008; 197: 218–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Johnson JR, Clabots C, Johnson JR, Clabots C. Sharing of virulent Escherichia coli clones among household members of a woman with acute cystitis. Clin Infect Dis 2006; 43: e101–e108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Richards CL, Richards CL. Urinary tract infections in the frail elderly: issues for diagnosis, treatment and prevention. Int Urol Nephrol 2004; 36: 457–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wagenlehner FME, Naber KG, Weidner W. Asymptomatic bacteriuria in elderly patients – significance and implications for treatment. Drugs Aging. 2005; 22: 801–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Polzin D. Chronic kidney disease. In: Bartges J, Polzin D. (eds). Nephrology and urology of small animals. Chichester, Ames: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011, pp 448–449. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Barsanti JA. Genitourinary infections. In: Greene CE. (ed.) Infectious diseases of the dog and cat. 4th ed. St Louis, MO: Elsevier/Saunders, 2012, p 1021. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Boyd LM, Langston C, Thompson K, et al. Survival in cats with naturally occurring chronic kidney disease (2000–2002). J Vet Intern Med 2008; 22: 1111–1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Syme HM, Markwell PJ, Pfeiffer D, Elliott J. Survival of cats with naturally occurring chronic renal failure is related to severity of proteinuria. J Vet Intern Med 2006; 20: 528–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S, May S. Methods to examine the scale of continuous covariates in the log hazard. Applied survival analysis: regression modelling of time-to-event data. 2nd ed. Ames: Wiley Interscience, 2008. pp 136–141. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S, May S. Assessing the proportional hazards assumption. Applied survival analysis: regression modelling of time-to-event data. 2nd ed. Ames: Wiley-Interscience, 2008, pp 177–184. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Barber PJ, Markwell PJ, et al. Incidence and prevalence of baterial urinary tract infections in cats with chronic renal failure. In: 17th Annual American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine Forum, Chigaco, IL, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bengtsson C, Bengtsson U, Bjorkelund C, et al. Bacteriuria in a population sample of women: 24-year follow-up study — results from the prospective population-based study of women in Gothenburg, Sweden. Scand J Urol Nephrol 1998; 32: 284–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Osborne CA, Klausner JS, Lees GE. Urinary-tract infections — normal and abnormal host defense-mechanisms. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 1979; 9: 587–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yuri K, Nakata K, Katae H, et al. Serotypes and virulence factors of Escherichia coli strains isolated from dogs and cats. J Vet Med Sci 1999; 61: 37–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jepson RE, Elliott J, Brodbelt D, Syme HM. Effect of control of systolic blood pressure on survival in cats with systemic hypertension. J Vet Intern Med 2007; 21: 402–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Allen TA, Jaenke RS, Fettman MJ. A technique for estimating progression of chronic renal failure in the dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1987; 190: 866–868. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]