Abstract

Objectives

The objective of this study was to compare the effects of ketamine and alfaxalone on the application of a validated feline-specific multidimensional composite pain scale (UNESP-Botucatu MCPS).

Methods

In a prospective, randomized, blinded, crossover trial, 11 adult cats (weight 4.4 ± 0.6 kg) were given dexmedetomidine (15 μg/kg) and hydromorphone (0.05 mg/kg) with either alfaxalone (2 mg/kg) or ketamine (5 mg/kg) as a single intramuscular injection for the induction of general anesthesia. After orotracheal intubation, general anesthesia (without surgery) was maintained for 32 mins with isoflurane, followed by atipamezole. The following parameters were recorded at baseline, 1–8 h and 24 h post-extubation: pain (pain expression and psychomotor subscales) and sedation scale scores. Alfaxalone treatment injection sites were examined for inflammation at baseline, postinjection, and 8 h and 24 h post-extubation.

Results

Psychomotor scores were higher with ketamine at hours 1 (3.5 [0–5.0], P <0.0001), 2 (2.5 [0–4.0], P <0.0001) and 3 (0.5 [0–4.0], P = 0.009) post-extubation compared with alfaxalone (hour 1, 0 [0–2]; hour 2, 0 [0–0]; hour 3, 0 [0–0]). Six cats in the ketamine group crossed the analgesic intervention threshold. In contrast, pain expression scores did not differ significantly between treatments at any time (P >0.05); one cat from each group crossed the analgesic intervention threshold. Sedation was greater with ketamine (1 [0–3], P = 0.02) than alfaxalone (0 [0–1]) 1 h post-extubation. No cats had visible inflammation at the injection sites at any time.

Conclusions and relevance

Ketamine has a confounding effect on the psychomotor subscale of the pain scale studied, which may lead to erroneous administration of rescue analgesia. In contrast, alfaxalone was not associated with significant increases in either pain subscale. These effects of ketamine should be considered when evaluating acute postoperative pain in cats.

Introduction

Perioperative pain in cats is commonly undertreated, as shown by multiple surveys, spanning differences in culture and veterinary training.1–7 Using ovariohysterectomy (OHE) as an example of a commonly performed surgical procedure, an older study reported analgesic use as low as 26%. 5 While there has been a trend to an increase in perioperative analgesic administration, with recent reports suggesting an improvement in analgesic use to 50–92%, this still leaves a significant number of animals receiving surgery without analgesia.1,7 An analgesic administration rate of 92% would result in an estimated 3500 OHE procedures performed without analgesia per month in Canada. 1

Undertreatment of pain results from numerous factors, including a perceived inability to assess pain and lack of a validated pain scale.2,4–6,8 Although a validated pain scale for acute pain has been available for dogs for several years, 9 equivalent scales for cats have only recently become available.10,11

It is anticipated that publication of these feline-specific pain scales will markedly improve veterinarian and technician ability to assess acute, postoperative pain reliably and consistently, and aid the decision-making process to administer analgesia. However, scale validation is potentially limited by the original study population, procedure(s) and drug protocol(s) assessed.12,13 Where this has been recognized, efforts have been made to assess validation in a heterogenous setting (different laboratory/clinic, observers, animal population, procedures and protocols).12,14–16 This process of assessing scale performance in a heterogenous setting is known as generalizability. 13

In contrast to the anesthetic protocol initially used to develop the UNESP-Botucatu multidimensional composite pain scale (MCPS; propofol, fentanyl, isoflurane), anesthetic protocols that include the dissociative agent ketamine are commonly administered in cats.2,7,17–19 Ketamine has the potential to induce emergence phenomena during recovery from general anesthesia, including hypersensitivity to touch and noise,20–23 which may interfere with a behavior-based scale. 10 This could explain the observation of Brondani et al that the assessment subscale that included wound palpation (‘pain expression’ subscale) was better at discriminating between analgesic treatments than the subscale consisting of general behavioral observations (‘psychomotor’ subscale) when ketamine was included in the anesthetic protocol. 10

The goal of the present study was to test the hypothesis that ketamine has a confounding effect on the UNESP-Botucatu MCPS by interfering with application of the psychomotor subscale. A secondary aim was to assess any interaction between alfaxalone and the UNESP-Botucatu MCPS.

Methods

Animals

This study was performed following institutional ethics approval (VSACC AC13-0146).

Eleven healthy cats from the teaching colony of the University of Calgary Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, with a median (range) age of 5 (4–14) years and mean ± SD body mass of 4.4 ± 0.6 kg were enrolled in a prospective, randomized, blinded, crossover trial. The study time line was as follows: 1 week of daily socialization and habituation to researchers, first experimental period (2 days), 2 weeks washout, second experimental period (2 days). The initial week of socialization was used to select cats for the study, based on inclusion criteria of interaction with researchers (MB, MW, MH, DP) and ease of handling. Cats were group-housed in rooms, with between three and six cats per room, were fed a combination of commercial dry and wet food, and had free access to fresh water, litter and enrichment (platforms at different heights, cat trees, toys). Rooms were on a 12 h light:dark cycle (lights on at 07:00), and temperature was maintained between 18.0 °C and 19.5 °C. A feline pheromone diffuser (Feliway; Ceva Animal Health) was used in the colony rooms for the duration of the study.

Experimental procedure

Following recruitment, each cat was randomized (random.org) to receive the first of two treatments. Treatment one (KetHD) was ketamine hydrochloride (5 mg/kg, 100 mg/ml, Vetalar; Bioniche Animal Health Canada), hydromorphone hydrochloride (0.05 mg/kg, 10 mg/ml; Sandoz Canada) and dexmedetomidine hydrochloride (15 μg/kg, 0.5 mg/ml, Dexdomitor; Zoetis). Treatment two (AlfHD) was alfaxalone (2 mg/kg, 10 mg/ml, Alfaxan; Jurox), hydromorphone hydrochloride (0.05 mg/kg) and dexmedetomidine hydrochloride (15 μg/kg). The selection of alfaxalone dose was based on researcher experience and the wish to limit the injectate volume to approximately 1 ml.

Cats were fasted for 12 h prior to each experiment, with the anesthesia portion of the experiment beginning at 08:00 (last cat extubated by 11:30).

On experimental days cats were moved to individual kennels containing a plastic igloo shelter, towel, litter tray and empty food bowl. Each kennel was wiped with feline pheromone. Each cat had a baseline assessment of a multidimensional composite pain scale, sedation scale and demeanor scale.10,24,25 The pain assessment scale is comprised of three subscales: pain expression, psychomotor and physiological. Only the pain expression and psychomotor subscales were applied as the physiological subscale requires preanesthetic information on arterial blood pressure and appetite that is not readily available in a clinical setting or obtainable from group housing. The pain expression subscale consists of four equally weighted items (miscellaneous behaviors, response to palpation of incision site and alternate site, and vocalization; scale range 0–12). In lieu of a surgical incision, the abdominal midline was palpated to mimic the incision site associated with OHE. The psychomotor subscale also consists of four equally weighted items (posture, comfort, activity and attitude; scale range 0–12). For each of these subscales, analgesic intervention thresholds were derived from Brondani et al, 10 indicating the probable requirement for rescue analgesia.

For each treatment, drugs were drawn up individually and mixed in a single syringe by an individual not involved in the pain or behavior assessments (DP). Treatment drugs were given intramuscularly (IM; lumbar epaxial muscle) within 10 mins of preparation. The injection site was clipped 3 days prior to the experiment. Following injection, each cat was returned to its kennel in the preparation room under observation. Ten minutes later the sedation scale was applied before transferring the cat to the anesthesia suite. Here the cat was positioned on a table in sternal recumbency and the larynx sprayed with 0.1 ml lidocaine 2%. After 30 s orotracheal intubation was performed. Quality of intubation (presence/absence of cough/swallow), number of attempts (one or more than one attempt) and requirement to deliver isoflurane by mask to facilitate intubation were recorded. If intubation was not possible owing to inadequate depth of general anesthesia, a face mask was used to administer isoflurane gas to effect and intubation attempted again. Once intubated, cats were placed in lateral recumbency and general anesthesia maintained with isoflurane (0.5%) carried in oxygen (1.5 l/min; Bain non-rebreathing system) for 32 mins. This time approximates the time from orotracheal intubation to extubation at a local clinic. 26 The following parameters were monitored and recorded at 5 min intervals using a physiologic monitor (Life Window LW9xVet; Digicare): saturation of hemoglobin with oxygen (probe placed on tongue), non-invasive blood pressure (oscillometric, pressure cuff placed on antebrachium), end-tidal carbon dioxide and esophageal temperature (probe inserted to seventh rib). Each cat was placed between a forced air warming device (below) and blanket (on top). Core body temperature was maintained between 37.2 °C and 40.0 °C. At the end of anesthesia, a final esophageal temperature was recorded, the anesthetic vaporizer turned off, atipamezole hydrochloride (75 μg/kg, 5 mg/ml, Antisedan; Zoetis) injected IM (lumbar epaxial muscle group, opposite treatment injection site) and meloxicam (0.2 mg/kg, 5 mg/ml Metacam; Boehringer-Ingelheim) injected subcutaneously (dorsal neck). Cats were disconnected from the breathing system following completion of injections and allowed to recover on the anesthesia table. The end of anesthesia was defined by extubation (when ear flick or head movement was observed), at which point the cat was returned to its empty kennel and placed in lateral recumbency. Cats remained in these kennels for the remainder of the assessment period, monitored every 15 mins after extubation until sternal recumbency was achieved, at which time the igloo, litter tray and food were added to the kennel. Pain, behavior and sedation scales were applied hourly post-extubation for 8 h. At the 8 h time point, additional food and water were offered. A final pain, behavior and sedation scale assessment was performed 24 h post-extubation, after which cats were returned to their colony housing. The treatment injection site was evaluated in the alfaxalone group for swelling and redness at baseline (prior to injection), postinjection (within 30 mins), 8 and 24 h postinjection.

All assessments were made by one of three trained personnel (MB, MW, MH), blinded to the treatment. Consistency of scoring between raters was compared with inter-rater agreement (intra-class correlation coefficient [ICC]) from data collected in an unrelated study and assessed as ‘very good’ (ICC ⩾0.81). 12 Injection site assessment was performed by a single observer (DP) using blinded photos taken at the assessment times.

Statistical methods

Postoperative temperatures were compared with paired t-tests. Sedation and pain were analyzed with a Friedman test with Dunn’s post-hoc test for within-group comparisons (each time point compared with baseline) and a Kruskall–Wallis test with a Dunn’s post-hoc test for between-group comparisons. Demeanor scale data were compared between groups with a Wilcoxon test. A Fisher’s exact test was used to evaluate the incidence of redness/swelling between treatment groups and intubation data (quality of intubation, number of attempts and requirement for isoflurane). Data are presented as mean ± SD and median (range). P values <0.05 were considered significant. Data were analyzed with commercial software (Graphpad Prism version 6.0b; GraphPad Software).

Results

One cat was excluded from the study owing to a misinjection.

Postoperative temperature did not differ between treatment groups (KetHD 38.4 ± 0.7 °C, AlfHD 38.2 ± 0.5 °C; P = 0.49).

Treatment groups did not differ in demeanor scores at baseline (KetHD 2 [1–5], AlfHD 1.5 [1–4]; P = 0.98) and could be classified as ‘friendly’ according to the scale descriptors. 25

Pain scores

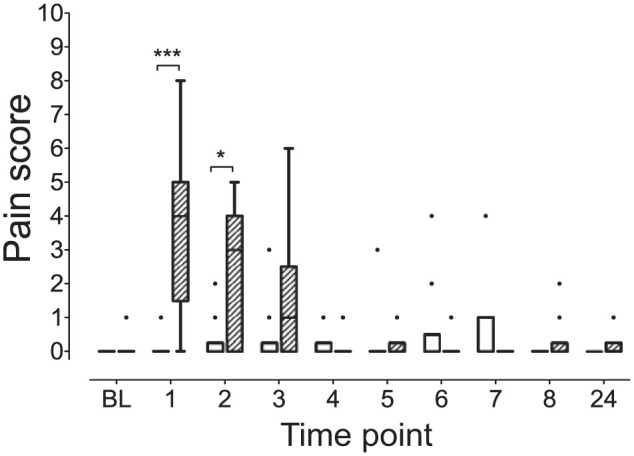

The KetHD treatment resulted in higher pain scores (pain expression and psychomotor subscales combined) at hours 1 (KetHD 4 [0–8], AlfHD 0 [0–1]; P = 0.0002) and 2 (KetHD 3 [0–5], AlfHD 0 [0–2]; P = 0.02) post-extubation (Figure 1). At hour 3, the difference in pain scores (KetHD 1 [0–6], AlfHD 0 [0–3]) was not significant (P >0.99). Within the KetHD group, pain scores were elevated at the 1 h time point compared with baseline (P <0.05). In contrast, the AlfHD group did not show changes in pain scores throughout the assessment period (P >0.9 for all comparisons).

Figure 1.

Pain scores from the combined pain expression and psychomotor subscales are elevated in the ketamine–hydromorphone–dexmedetomidine (KetHD) group. Hatched box is the KetHD group. Clear box is the alfaxalone–hydromorphone–dexmedetomidine group. Box contains the median (horizontal line) and is limited by the interquartile range (IQR); whiskers are delimited by 25th percentile minus IQR and 75th percentile plus IQR (Tukey whiskers). Data points exceeding this calculated range are plotted as individual points. 1, 2, 3, etc, are hours post-extubation. ***P = 0.0002, *P = 0.02 BL = baseline.

Evaluation of the individual pain scale subscales revealed the following.

Psychomotor subscale

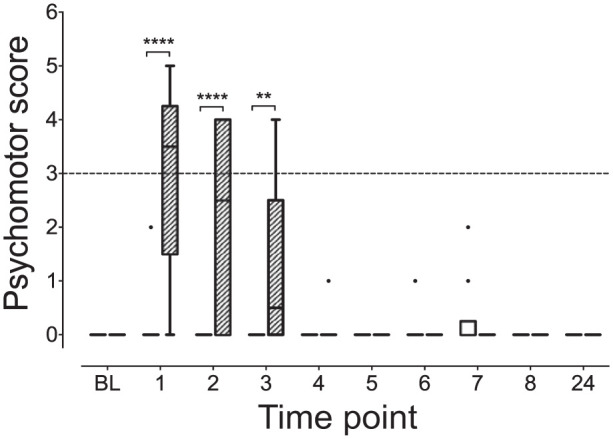

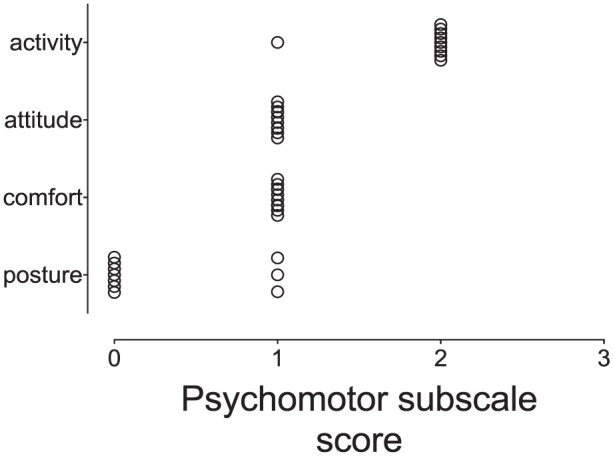

The KetHD group had higher scores at hour 1 (KetHD 3.5 [0–5.0], AlfHD 0 [0–2]; P <0.0001), hour 2 (KetHD 2.5 [0–4.0], AlfHD 0 [0–0]; P <0.0001) and hour 3 (KetHD 0.5 [0–4.0], AlfHD 0 [0–0]; P = 0.009 [Figure 2]) compared with AlfHD. There were no changes in the psychomotor subscale scores within the AlfHD group over time (P >0.9 for all comparisons), but the KetHD group showed a significant increase at hour 1 (3.5 [0–5.0]; P = 0.01) compared with baseline (0 [0–0]). The comparison at hour 2 did not achieve statistical significance (P = 0.09). Furthermore, six cats in the KetHD group crossed the analgesic intervention threshold (subscale score >3/12) at 1 h. Four of these six cats maintained scores above the threshold level at hour 2. An additional cat received a score above the intervention threshold at hour 2. At hour 3, two cats maintained scores above the threshold value. The items of the subscale that resulted in the elevated scores were predominantly those associated with behavior: activity, attitude and comfort (Figure 3). These three items contributed to 30/33 (91%) of item scores greater than zero, with the remaining three scores coming from the posture item.

Figure 2.

Psychomotor subscale scores are higher in the ketamine–hydromorphone–dexmedetomidine (KetHD) than the alfaxalone–hydromorphone–dexmedetomidine treatment group. The broken horizontal line represents the analgesic intervention threshold, indicating potential requirement for rescue analgesia. In the KetHD group, six cats crossed this threshold at hour 1 and an additional cat at hour 2 post-extubation. ****P <0.0001, **P = 0.009. See Figure 1 for full legend. BL = baseline

Figure 3.

A scatter plot of individual item scores (activity, attitude, comfort, posture) comprising the psychomotor subscale from cats (ketamine-hydromorphone-dexmedetomidine group) that crossed the analgesic intervention threshold shows the majority of scores resulting from changes in behavioral items. Only three scores in the posture item exceeded zero

Pain expression subscale

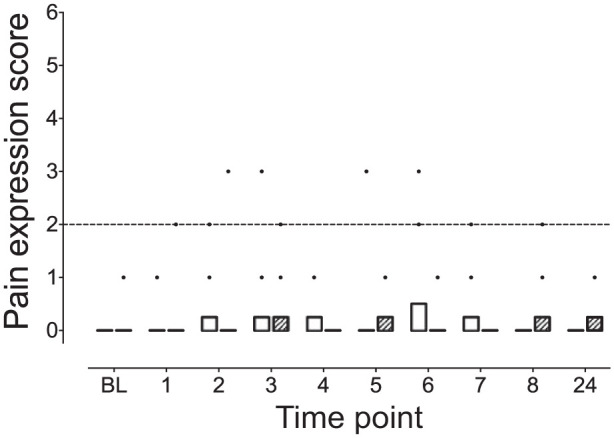

Scores between treatment groups did not reveal any significant differences (P >0.9 for all comparisons; Figure 4). Within each treatment group there were no significant changes in pain expression subscale scores over time (P >0.9 for all comparisons). Two cats, one from each treatment group, crossed the analgesic intervention threshold (subscale score >2/12). One of these cats was responsible for three of the four elevated scores after receiving the AlfHD treatment. The items of the subscale contributing to the elevated scores were behavioral (body position and undisturbed behavior and vocalization). There were no responses to palpation in either group.

Figure 4.

Pain expression subscale scores did not differ between the ketamine–hydromorphone–dexmedetomidine (KetHD) and alfaxalone–hydromorphone–dexmedetomidine (AlfHD) treatment groups (P >0.9 for all comparisons). The broken horizontal line represents the analgesic intervention threshold, indicating the potential requirement for rescue analgesia. Two cats crossed this threshold, with one cat crossing once following KetHD administration and the other cat crossing three times following AlfHD treatment. See Figure 1 for full legend. BL = baseline.

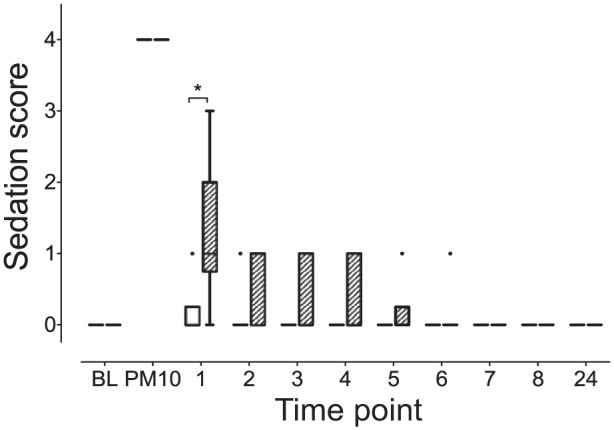

Sedation

KetHD treatment resulted in significantly higher sedation scores at 1 h (KetHD 1 [0–3], AlfHD 0 [0–1]; P = 0.02 [Figure 5]). At hours 2–4, while more cats in the ketamine group had increased sedation scores, the comparisons were not statistically significant: hour 2 (KetHD 1 [0–1], AlfHD 0 [0–1]; P = 0.19); hour 3 (KetHD 0 [0–1], AlfHD 0 [0–0]; P = 0.62); hour 4 (KetHD 0 [0–1], AlfHD 0 [0–0]; P = 0.62). Within each treatment group, sedation scores 10 mins after premedication were significantly greater than at baseline (baseline 0 [0–0], post-premedication 4 [4–4]; P <0.01, both groups). In the KetHD group sedation levels were also greater at 1 h post-extubation compared with baseline (P <0.05).

Figure 5.

Ketamine–hydromorphone–dexmedetomidine results in prolonged sedation compared with alfaxalone–hydromorphone–dexmedetomidine at 1 h post-extubation. *P = 0.02. See Figure 1 for full legend BL = baseline. PM10 = 10 mins after intramuscular injection of treatment.

Injection sites

Four of the photographed images could not be scored owing to movement artefact. Of the remaining 36 images taken to accompany AlfHD injection (10 at baseline, 10 postinjection, nine at 8 h and seven at 24 h) no signs of redness or swelling were observed.

Orotracheal intubation

The number of animals requiring isoflurane to facilitate orotracheal intubation, quality of intubation and number of attempts to achieve intubation did not differ between groups (P >0.05, all comparisons; Table 1).

Table 1.

Intubation data for alfaxalone and ketamine treatment groups

| Intubation parameters |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isoflurane required | Isoflurane not required | Cough/swallow observed | No cough/swallow | More than one intubation attempt | One intubation attempt | |

| Alfaxalone | 2 | 8 | 0 | 9 | 1 | 8 |

| Ketamine | 2 | 8 | 2 | 8 | 1 | 8 |

No significant differences were observed for any comparison (isoflurane requirement, presence of cough/swallow at intubation, number of intubation attempts; P >0.05). Maximum number of intubation attempts was two (once in each treatment group). Data were missing for intubation quality (one animal in alfaxalone group) and number of attempts (one animal from each treatment group)

Discussion

The recent publication of two validated feline-specific pain scales provides essential tools for the assessment and appropriate management of acute pain in cats.10,27 Historically, pain management in cats is poor, and limited pain assessment ability has been cited as a contributing factor.2,5,28

Assessment of pain scale reliability (measurement error between and within observers) and validity (does a scale measure what it is designed to measure?) is labor intensive, though recent years have seen a dramatic increase in the number of validated scales in a wide range of species.9–12,14,15,29 A potential misinterpretation of scale validation is the assumption of generalizability. Generalizability refers to the applicability of a scale to a range of different contexts. However, where the context of the original validation study differs substantially from the new context, generalizability should not be assumed. 13 Difficulty arises in judging the relevance of these differences, ranging from population (sex, age, disease, temperament, drug therapy) to environment (sound, light, temperature) and personnel (sex, experience and training). Indeed, the stark confounding effect of ketamine shown by these data illustrate the risk of such an assumption. The administration of ketamine resulted in an increase in psychomotor subscale scores sufficient to exceed the analgesic intervention threshold, with a summative effect (both subscales combined) on the overall pain score.

The psychomotor subscale consists of four behavioral assessment items, three of which (activity, attitude and comfort) include descriptions of behaviors that overlap with behaviors that may be observed during recovery from ketamine-based anesthesia. These subscale item descriptors include ‘dissociated’ behavior with minimal or no interaction with the observer, a reluctance to move, moving more than normal and indifference to surroundings. 10 The behaviors observed during recovery (emergence phenomena) from ketamine-based anesthesia include ataxia, hyper-reflexia, sensitivity to touch and noise, and increased motor activity.20–23 These have been documented since the 1970s,30,31 though the incidence of observed emergence phenomena varies as a result of variation in the assessment and scoring of recovery, administered doses and presence of other drugs.21,23,30,32,33 For example, benzodiazepines, commonly used to provide muscle relaxation and extend the duration of ketamine, may make the clinical picture more difficult to interpret as they can contribute to behavioral changes. 33

These emergence phenomena are the likely cause of the observed psychomotor subscale interference. The sources of these emergence phenomena are not clear but appear to involve a ketamine-induced alteration in brain neurotransmitters, including a disruption of auditory and visual processing.22,23 An abnormal auditory response (to handclap) was observed in cats receiving ketamine and dexmedetomidine (but not dexmedetomidine alone or with butorphanol). 22 The consequences of this confounding effect of ketamine are that 6/10 cats in the KetHD treatment group qualified for rescue analgesia based on the psychomotor analgesic intervention threshold, while no animals in the AlfHD group crossed the threshold.

The increase in psychomotor subscale scores observed coincided with the presence of sedation at 1 h after extubation. The overlap between the two scales highlights the difficulty of assessing pain in the presence of sedation. Calvo et al acknowledged this potential interaction when developing their pain scale, electing to not assign a pain score when sedation was present. 11 Nevertheless, waiting until sedation has subsided is not always practical and some drug classes, such as a-2 adrenergic agonists, provide sedation in addition to analgesia. In the presence of sedation a pragmatic approach would be to administer analgesics if there is any doubt that analgesia may be insufficient, followed by reassessment of the patient.

In contrast, the pain expression subscale is more dependent on an evoked-response (response to palpation), which accounts for two of the four subscale items. From our data it appears that eliciting an evoked-response may differentiate pain- and drug-related behaviors.

Unlike the results observed from the psychomotor subscale, the pain expression subscale results did not change over time or between treatment groups. However, two cats did cross the intervention threshold. The cause of this increase resulted from the behavioral components (miscellaneous behaviors [observation of body position and behavior] and vocalization [at rest and in response to observer interaction]) of the subscale. In the absence of group differences these results highlight the influence of individual variability, avoidance of a prescriptive approach to applying analgesic intervention scores and the importance of clinical judgment. 27

Based on our findings, within the constraints of a non-surgical study, application of the pain expression subscale alone could help discriminate between sedation and pain, particularly when a ketamine-based protocol is administered. Injectable anesthetic protocols that include ketamine are commonly employed in cats in both companion animal and the trap–neuter–return settings, conferring the benefit of a dose-dependent effect, from sedation to general anesthesia, in a small injectate volume.17–19,26

In contrast to ketamine, the results from the alfaxalone-based protocol support the applicability of both psychomotor and pain expression subscales of the UNESP-Botucatu MCPS. 10 Development of the UNESP-Botucatu MCPS used propofol as the anesthetic induction agent, which shares a mechanism of action with alfaxalone (g-aminobutyric acidA receptor agonism). Importantly, the propofol-based protocol (co-administered drugs included fentanyl, isoflurane, morphine and ketoprofen) was used to derive an analgesic intervention threshold (in adult female cats scheduled for OHE). 10 In support of our findings, when the same study tested the derived analgesic intervention thresholds in a clinical setting, which included the use of intravenous ketamine and diazepam as part of the anesthetic protocol, the authors reported the pain expression subscale as providing better discrimination of analgesic use than the other subscales (psychomotor, physiological). 10 In the context of our data, we postulate that this observation resulted from behavioral changes associated with ketamine. To our knowledge, no other studies have used the pain scale developed by Brondani et al with a ketamine-based anesthetic protocol. 10 In contrast, recent work employing this scale showed efficacy with propofol-based anesthetic protocols, increasing confidence that the scale does translate to a heterogenous setting, illustrating generalizability.34,35

A recently published feline-specific composite measure pain scale (unpublished at the time of conducting this study) has a greater weighting of scores towards an evoked-response (eight out of a maximum of 16 points). It will be interesting to see how it performs in a heterogenous setting. 11

A potential complication of the increased sedation period associated with ketamine is the observation that 61% of general anesthetic- and sedation-related deaths in cats occur during recovery, with the majority of these occurring within the first 3 h of completing a procedure. 36 In addition to the suggestion of closer monitoring, 36 a shortened recovery period, without compromising pain management, is appealing. 26 The concept of optimizing recovery, known as enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS; also known as fast-track surgery), is a multi-disciplinary approach to perioperative management with the goal of a rapid, comfortable recovery.37,38 Such an approach has proved successful in a range of surgery types, and a high level of supporting evidence (meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials) exists.39–42 Application of ERAS in veterinary medicine is in its infancy, 26 and the duration of postanesthetic sedation observed here, and by others with similar injectable protocols,19,43 warrants further investigation.

The use of alfaxalone in cats has been associated with rough recoveries in one study, 44 while others have found recoveries to be similar in quality to intravenous propofol or ketamine and diazepam.20,45,46 The source(s) of this inconsistency is(are) likely to be multifactorial and may be associated with drug dose, route of administration, the presence of other sedative/analgesic/anesthetic agents and environmental factors. We did not specifically score recovery quality but prolonged rough recoveries would be expected to have affected the sedation and pain scale assessments.

The AlfHD protocol did not result in visible swelling or redness of the injection site over the observation period, confirming a clinical impression that this drug combination does not result in visible tissue damage when administered as described here.

Intubation quality data were similar for both treatments, though firm conclusions cannot be drawn owing to the limitations of sample size and low incidence of complications. The need to administer isoflurane to facilitate intubation was similar to previous findings with KetHD, where 80% of cats were intubated without isoflurane. 26

Limitations of this study include the use of a modified demeanor scale and unvalidated sedation scale. The group housing of the cats precluded use of the full demeanor scale; however, our cats exhibited demeanour scores lower than those of Zeiler et al, 25 with the same items omitted (median 6, range 0–11) (G Zeiler, 2014, personal communication). This was not surprising as we purposely selected social, friendly cats to simplify interpretation of the data. The sedation scale used was based on that of Slingsby et al. 47 To our knowledge, no validated sedation scale exists for use in cats. This limits comparison of the sedation scores reported here to other studies. Interestingly, the scale was able to discriminate differing levels of sedation between the treatment groups but was unable to identify cats requiring isoflurane to allow orotracheal intubation.

Conclusions

These data show a confounding effect on the assessment of pain using the UNESP-Botucatu MCPS when ketamine is included in the anesthetic protocol. Specifically, ketamine increases psychomotor, but not pain expression, subscale scores. This effect could lead to the unnecessary administration of analgesics and focusing on the results of the pain expression subscale may be more accurate. Additionally, ketamine resulted in a slower recovery with an increase in postanesthetic sedation. In contrast, alfaxalone was not associated with significant increases in either subscale and sedation was not present in the recovery period.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Gregory Muench and Miss Barbara Smith for facilitating the study and for their technical support.

Footnotes

The authors do not have any potential conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding: This work was supported by Zoetis and the Investigative Medicine veterinary student rotation of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Calgary (MB, MH). MW received a summer studentship from Zoetis. Drugs were supplied by Zoetis (dexmedetomidine [Dexdomitor], atipamezole [Antisedan]); Jurox (alfaxalone [Alfaxan]); and CEVA (Feliway). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Accepted: 22 May 2015

References

- 1. Hewson CJ, Dohoo IR, Lemke KA. Perioperative use of analgesics in dogs and cats by Canadian veterinarians in 2001. Can Vet J 2006; 47: 352–359. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hugonnard M, Leblond A, Keroack S, et al. Attitudes and concerns of French veterinarians towards pain and analgesia in dogs and cats. Vet Anaesth Analg 2004; 31: 154–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Joubert KE. The use of analgesic drugs by South African veterinarians. J S Afr Vet Assoc 2001; 72: 57–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Joubert KE. Anaesthesia and analgesia for dogs and cats in South Africa undergoing sterilisation and with osteoarthritis – an update from 2000. J S Afr Vet Assoc 2006; 77: 224–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lascelles BDX, Capner CA, Waterman-Pearson AE. Current British veterinary attitudes to perioperative analgesia for cats and small animals. Vet Rec 1999; 145: 601–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Watson AD, Nicholson A, Church DB, et al. Use of anti-inflammatory and analgesic drugs in dogs and cats. Aust Vet J 1996; 74: 203–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Williams VM, Lascelles BD, Robson MC. Current attitudes to, and use of, peri-operative analgesia in dogs and cats by veterinarians in New Zealand. N Z Vet J 2005; 53: 193–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hewson CJ, Dohoo IR, Lemke KA. Factors affecting the use of postincisional analgesics in dogs and cats by Canadian veterinarians in 2001. Can Vet J 2006; 47: 453–459. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Morton CM, Reid J, Scott EM, et al. Application of a scaling model to establish and validate an interval level pain scale for assessment of acute pain in dogs. Am J Vet Res 2005; 66: 2154–2166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brondani JT, Mama KR, Luna SP, et al. Validation of the English version of the UNESP-Botucatu multidimensional composite pain scale for assessing postoperative pain in cats. BMC Vet Res 2013; 9: 143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Calvo G, Holden E, Reid J, et al. Development of a behaviour-based measurement tool with defined intervention level for assessing acute pain in cats. J Small Anim Pract 2014; 55: 622–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Oliver V, De Rantere D, Ritchie R, et al. Psychometric assessment of the Rat Grimace Scale and development of an analgesic intervention score. PLoS One 2014; 9: e97882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Streiner DL, Norman GR. Reliability. Health measurement scales. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008, pp 167–210. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Langford DJ, Bailey AL, Chanda ML, et al. Coding of facial expressions of pain in the laboratory mouse. Nat Methods 2010; 7: 447–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sotocinal SG, Sorge RE, Zaloum A, et al. The Rat Grimace Scale: a partially automated method for quantifying pain in the laboratory rat via facial expressions. Mol Pain 2011; 7: 55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Leach MC, Klaus K, Miller AL, et al. The assessment of post-vasectomy pain in mice using behaviour and the Mouse Grimace Scale. PLoS One 2012; 7: e35656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cistola AM, Golder FJ, Centonze LA, et al. Anesthetic and physiologic effects of tiletamine, zolazepam, ketamine, and xylazine combination (TKX) in feral cats undergoing surgical sterilization. J Feline Med Surg 2004; 6: 297–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Williams LS, Levy JK, Robertson SA, et al. Use of the anesthetic combination of tiletamine, zolazepam, ketamine, and xylazine for neutering feral cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2002; 220: 1491–1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Polson S, Taylor PM, Yates D. Analgesia after feline ovariohysterectomy under midazolam-medetomidine-ketamine anaesthesia with buprenorphine or butorphanol, and carprofen or meloxicam: a prospective, randomised clinical trial. J Feline Med Surg 2012; 14: 553–559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gieseg M, Hon H, Bridges J, et al. A comparison of anaesthetic recoveries in cats following induction with either alfaxalone or ketamine and diazepam. N Z Vet J 2014; 62: 103–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Larenza MP, Althaus H, Conrot A, et al. Anaesthesia recovery quality after racemic ketamine or S-ketamine administration to male cats undergoing neutering surgery. Schweiz Arch Tierheilkd 2008; 150: 599–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Selmi AL, Mendes GM, Lins BT, et al. Evaluation of the sedative and cardiorespiratory effects of dexmedetomidine, dexmedetomidine-butorphanol, and dexmedetomidine-ketamine in cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2003; 222: 37–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wright M. Pharmacologic effects of ketamine and its use in veterinary medicine. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1982; 180: 1462–1471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Slingsby LS, Lane EC, Mears ER, et al. Postoperative pain after ovariohysterectomy in the cat: a comparison of two anaesthetic regimens. Vet Rec 1998; 143: 589–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zeiler GE, Fosgate GT, van Vollenhoven E, et al. Assessment of behavioural changes in domestic cats during short-term hospitalisation. J Feline Med Surg 2014; 16: 499–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hasiuk M, Brown D, Cooney C, et al. Application of fast-track surgery principles to evaluate effects of atipamezole on recovery and analgesia following ovariohysterectomy in cats anesthetized with dexmedetomidine-ketamine-hydromorphone. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2015; 246: 645–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Reid J, Nolan AM, Hughes JML, et al. Development of the short-form Glasgow Composite Measure Pain Scale (CMPS-SF) and derivation of an analgesic intervention score. Anim Welf 2007; 16: 97–104. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dohoo SE, Dohoo IR. Factors influencing the postoperative use of analgesics in dogs and cats by Canadian veterinarians. Can Vet J 1996; 37: 552–556. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dalla Costa E, Minero M, Lebelt D, et al. Development of the Horse Grimace Scale (HGS) as a pain assessment tool in horses undergoing routine castration. PLoS One 2014; 9: e92281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Beck CC. Answers to some common questions about Vetalar (ketamine HCl). Vet Med Small Anim Clin 1976; 905–908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Reid JS, Frank RJ. Prevention of undesirable side reactions of ketamine anesthesia in cats. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 1972; 8: 115–119. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Biermann K, Hungerbuhler S, Mischke R, et al. Sedative, cardiovascular, haematologic and biochemical effects of four different drug combinations administered intramuscularly in cats. Vet Anaesth Analg 2012; 39: 137–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ilkiw JE, Suter C, McNeal D, et al. The optimal intravenous dose of midazolam after intravenous ketamine in healthy awake cats. J Vet Pharmacol Ther 1998; 21: 54–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Warne LN, Beths T, Holm M, et al. Comparison of perioperative analgesic efficacy between methadone and butorphanol in cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2013; 243: 844–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Warne LN, Beths T, Holm M, et al. Evaluation of the perioperative analgesic efficacy of buprenorphine, compared with butorphanol, in cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2014; 245: 195–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Brodbelt DC, Blissitt KJ, Hammond RA, et al. The risk of death: the confidential enquiry into perioperative small animal fatalities. Vet Anaesth Analg 2008; 35: 365–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kehlet H. Multimodal approach to control postoperative pathophysiology and rehabilitation. Br J Anaesth 1997; 78: 606–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kehlet H, Wilmore DW. Multimodal strategies to improve surgical outcome. Am J Surg 2002; 183: 630–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hoffmann H, Kettelhack C. Fast-track surgery – conditions and challenges in postsurgical treatment: a review of elements of translational research in enhanced recovery after surgery. Eur Surg Res 2012; 49: 24–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Spanjersberg WR, Reurings J, Keus F, et al. Fast track surgery versus conventional recovery strategies for colorectal surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011; CD007635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Varadhan KK, Neal KR, Dejong CH, et al. The enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) pathway for patients undergoing major elective open colorectal surgery: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Nutr 2010; 29: 434–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zhu F, Lee A, Chee YE. Fast-track cardiac care for adult cardiac surgical patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012; 10: CD003587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zeiler GE, Dzikiti BT, Fosgate GT, et al. Anaesthetic, analgesic and cardiorespiratory effects of intramuscular medetomidine-ketamine combination alone or with morphine or tramadol for orchiectomy in cats. Vet Anaesth Analg 2014; 41: 411–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Grubb TL, Greene SA, Perez TE. Cardiovascular and respiratory effects, and quality of anesthesia produced by alfaxalone administered intramuscularly to cats sedated with dexmedetomidine and hydromorphone. J Feline Med Surg 2013; 15: 858–865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mathis A, Pinelas R, Brodbelt DC, et al. Comparison of quality of recovery from anaesthesia in cats induced with propofol or alfaxalone. Vet Anaesth Analg 2012; 39: 282–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Murison PJ, Martinez Taboada F. Effect of propofol and alfaxalone on pain after ovariohysterectomy in cats. Vet Rec 2010; 166: 334–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Slingsby LS, Waterman-Pearson AE. Comparison of pethidine, buprenorphine and ketoprofen for postoperative analgesia after ovariohysterectomy in the cat. Vet Rec 1998; 143: 185–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]