Abstract

A locus containing a gene with homology to ccpA of other bacteria has been cloned from Streptococcus mutans LT11, sequenced, and named regM. Upstream of the regM gene, on the opposite strand, is a gene encoding an X-Pro dipeptidase, pepQ. A 14-bp palindromic sequence with homology to the consensus catabolite-responsive element sequence lay in the promoter region between the two genes. To study the function of regM, the gene was inactivated by insertion of an antibiotic resistance marker. Diauxic growth of S. mutans on a number of sugars in the presence of glucose was not affected by disruption of regM. The loss of RegM increased glucose repression of α-galactosidase, mannitol-1-P dehydrogenase, and P-β-galactosidase activities. These results suggest that while RegM can affect catabolite repression in S. mutans, it does not conform to the model proposed for CcpA in Bacillus subtilis.

The ability of oral streptococci such as Streptococcus mutans to utilize a wide range of substrates has an important role in the colonization of dental plaque and the process of dental caries. Fermentation of carbohydrates generates organic end products which cause the demineralization of the tooth enamel leading to caries, and S. mutans is extremely versatile in its utilization of a variety of carbohydrates, ranging from monosaccharides (glucose, galactose, and fructose), disaccharides (maltose, lactose, and sucrose), and trisaccharides (raffinose) to high-molecular-weight dextran, fructan, and starch (1, 48). The source of these carbohydrates may be the host’s salivary glycoproteins, the diet, or polymer formed from sucrose by S. mutans or by other plaque bacteria. Thus, the availability and type of carbohydrates in dental plaque vary enormously, and S. mutans has particularly efficient mechanisms for exploiting these fluctuating conditions. One such mechanism is catabolite repression whereby the expression of genes for certain catabolic enzymes is repressed in the presence of readily metabolized carbon sources, for example, glucose.

Catabolite repression in gram-negative bacteria such as Escherichia coli, where it is a positive regulatory mechanism involving catabolite activator protein and cyclic AMP (cAMP), is well understood. However catabolite repression in gram-positive bacteria, including S. mutans, is clearly different, as little or no cAMP is produced (35). Recent studies with several species of gram-positive bacteria, particularly Bacillus subtilis, have suggested a regulatory mechanism for catabolite repression involving the catabolite control protein, CcpA (reviewed in reference 36). In mutants lacking CcpA, a member of the LacI-GalR family of bacterial regulatory proteins, a number of enzymes show relief from catabolite repression (reviewed in reference 14). CcpA binds to a catabolite-responsive element (CRE) within or near the promoter region of targeted genes; this binding is thought to prevent transcription. CcpA also interacts with HPr, a component of the phosphoenolpyruvate:sugar phosphotransferase system (PTS), when the latter is phosphorylated on Ser-46 (5). Phosphorylation of HPr is a consequence of glycolysis and is thought to enable CcpA to bind to CRE, although binding has been demonstrated both in the presence (7) and absence (18) of phosphorylated HPr.

The selective use of sugars by S. mutans has been demonstrated by diauxic growth on a mixture of sugars (48). The mechanism by which this selection occurs is unknown, though there is some evidence that the model for catabolite repression in B. subtilis may also operate in oral streptococci. PTS-defective mutants of S. mutans do not exhibit diauxic growth on glucose and lactose (22), and uptake of raffinose by a ptsI mutant of S. mutans was relieved from glucose inhibition, also suggesting that the PTS system is involved in the regulation of the msm multiple sugar metabolism system (3). Several genes, including aga, fruA, mtlD (15), and dexB (33), in S. mutans have CRE-like sequences near their translational start sites. CcpA-like proteins have been identified in Streptococcus salivarius and Streptococcus sanguis by Western blot analysis with antibodies against the Bacillus megaterium CcpA (21). To investigate the involvement of such a protein in catabolite repression in S. mutans, we isolated a ccpA-like gene and determined the effect of its insertional inactivation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

Bacterial strains and plasmids are listed in Table 1. S. mutans was grown without agitation in either THYE (Todd-Hewitt [Oxoid], 0.5% [wt/vol] yeast extract), brain heart infusion (Oxoid), TYE (10 g of tryptone liter−1, 5 g of yeast extract liter−1, 20 mM KPO4-NaPO4 buffer [pH 7.5]), or the semidefined medium of Terleckyj et al. (46) either with amino acids or modified by the replacement of amino acids with 0.5% (wt/vol) casein hydrolysate (31). Carbohydrates were added as required at 0.5% (wt/vol) unless otherwise stated. When required, erythromycin (10 μg ml−1) or tetracycline (15 μg ml−1) was used for selection in S. mutans, and ampicillin (100 μg ml−1), erythromycin (400 μg ml−1), or tetracycline (15 μg ml−1) was used for selection in E. coli.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Reference and/or source |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | ||

| JM83 | F−ara Δ(lac-proAB) rpsL (Strr) [φ80dlacΔ(lacZ)M15]thi | 52 |

| XL1-Blue MRF′ | Δ(mcrA)183 Δ(mcrCB-hsdSMR-mrr)173 endA1 supE44 thi-1 recA1 gyrA96 relA1 lac[F′ proAB lacIqZΔM15 Tn10 (Tetr)] | Stratagene |

| XLOLR | Δ(mcrA)183 Δ(mcrCB-hsdSMR-mrr)173 endA1 thi-1 recA1 gyrA96 relA1 lac[F′ proAB lacIqZΔM15 Tn10 (Tetr)] Su− λr | Stratagene |

| S. mutans | ||

| LT11 | 45 | |

| LT11 regM | regM::Tet Tetr | This study |

| LT11 pepQ | pepQ::pVA8912 Ermr | This study |

| GS-5 | Laboratory strain | |

| GS-5 regM | regM::pVA8912 Ermr | This study |

| GS-5 pepQ | pepQ::pVA8912 Ermr | This study |

| Pro-1 | GS-5 Tn916, Tetr, proline auxotroph of GS-5 | 28 |

| Pro-1 regM | regM::pVA8912 Tetr Ermr | This study |

| pepQ::pVA8912 Tetr Ermr | This study | |

| Vectors | ||

| Lambda Zap Express | Kanr | Stratagene |

| pGEM-T | Apr, 3′ T overhangs | Promega |

| pUC19 | Apr | 52 |

| pVA8912 | pVA8911 without 412-bp PvuII fragment, Ermr | H. Malke (23) |

| pLN2 | Apr Tetr | 27 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pOB208 | pepQ regM amy (N-terminus) Kanr | This study |

| pOB209 | regM amy Kanr | This study |

| pOB210 | regM (C-terminus) amy Kanr | This study |

| pOB215 | pepQ regM amy (N-terminus) Kanr | This study |

DNA manipulations.

DNA manipulations and isolation of plasmid DNA were done by standard procedures (37). Southern blot analysis was carried out by using digoxigenin-labeled probes according to manufacturer’s instructions (Boehringer Mannheim). Chromosomal DNA preparations from S. mutans were as previously described (47).

PCR amplification.

S. mutans chromosomal DNA was used as the template in a 100-μl reaction mixture containing 200 pmol of each primer, 200 μM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 2.5 U of ThermoprimePLUS DNA polymerase (Advanced Biotechnologies), and reaction buffer. The PCR procedure consisted of 35 cycles of 95°C for 1 min, 50°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min. The product was eluted from an agarose gel after electrophoresis and cloned into pGEM-T (Promega).

Construction of a gene library and screening.

Chromosomal DNA from S. mutans LT11 was partially restricted with Sau3A and size fractionated by gel electrophoresis. The 4- to 12-kbp size range was eluted from the gel, ligated into the BamHI-cut arms of Lambda ZAP Express (Stratagene), packaged, and amplified according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Plaques were transferred to nylon membrane and hybridized with DNA probes labeled with digoxygenin by the random-primer method as instructed by the manufacturer (Boehringer Mannheim). The pBK-CMV phagemid containing hybridizing inserts were excised from the Lambda ZAP Express vector as described by Stratagene.

DNA sequencing.

Automated DNA sequencing (ABI) was performed by the Molecular Biology Facility, University of Newcastle upon Tyne. Sequencing was carried out with the universal and reverse primers or custom oligonucleotides on subclones in pUC vectors or PCR products cloned into pGEM-T. All sequencing was in both directions, using overlapping clones. DNA and protein sequences were manipulated by using IBI-Pustell and PC-Gene software packages.

Chromosomal inactivations.

To construct a regM insertion mutant, the cloned regM PCR product was cloned into pVA8912. A cassette encoding tetracycline resistance from pLN2 was inserted into the unique BglII site at position 1750, and the plasmid was linearized before transformation of S. mutans. The tetracycline resistance cassette was integrated into the regM gene by double crossover.

To inactivate the pepQ gene, an internal fragment of the gene was cloned into appropriate sites in plasmid pVA8912, which replicates in E. coli but not streptococci, thus integrating into the chromosome in a single crossover event. pVA8912 expresses erythromycin resistance in both E. coli and S. mutans.

To inactivate regM in S. mutans Pro-1, which already carries a tetracycline marker, an internal fragment of the gene was cloned in plasmid pVA8912 and integrated into the S. mutans chromosome by a single crossover event.

S. mutans LT11 was transformed by the addition of plasmid DNA to cells in early exponential growth in THYE; cultures were incubated for a further 2 h before aliquots were plated on brain heart infusion agar supplemented with antibiotic. S. mutans GS-5 and Pro-1 were transformed by electroporation using the heat shock method described by McLaughlin and Ferretti (25). Southern blot analysis was used to confirm integration of the plasmids into the appropriate gene on the S. mutans chromosome.

SDS-PAGE and Western blotting.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and Western blot analysis were carried out as previously described (10, 34), and CcpA-related proteins were detected with rabbit polyclonal antiserum to B. megaterium CcpA kindly provided by Elke Küster (21).

Determination of diauxic growth curves.

Cells were grown overnight in either TYE or semidefined medium containing 0.5% (wt/vol) glucose. Overnight cultures were harvested, washed twice in sugar-free medium, and added to fresh medium containing either 6 mM glucose or 6 mM glucose and 6 mM secondary carbohydrate to a standard optical density at 620 nm. Cultures were incubated at 37°C, and samples were taken every 30 min in order to monitor growth spectrophotometrically.

Determination of enzyme activities.

Cells of S. mutans were harvested by centrifugation, washed twice in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), and resuspended in a small volume of the same buffer. Cell extracts were prepared by sonicating the cells for 10 1-min pulses in the presence of 0.1-mm-diameter glass beads, with cooling on ice. Extracts were centrifuged in a microcentrifuge to remove beads and cell debris. Protein concentrations were determined by using Coomassie protein assay reagent (Pierce), with bovine serum albumin as a standard. For α-galactosidase, mannitol-1-P dehydrogenase, and P-β-galactosidase assays, S. mutans was grown in THYE supplemented with 0.5% (wt/vol) inducing sugar, with or without the addition of glucose to 0.5% (wt/vol). For determination of α-galactosidase activities, p-nitrophenyl-α-galactoside was added to cell extracts at a final concentration of 10 mM. Assays were performed at 37°C in a microtiter tray, and the change in absorbance at 405 nm determined with a Titertek plate reader.

For determination of mannitol-1-P dehydrogenase activity, cell extracts were incubated at room temperature in a reaction mixture containing 190 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), NAD (0.6 mg ml−1), and mannitol-1-P (0.8 mg ml−1). The increase in NADH was monitored in a microtiter tray at 340 nm.

For determination of P-β-galactosidase activities, cell extracts were incubated in a reaction mixture containing 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5), 1 mM MgCl2, and 0.88 mg of o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside ml−1 at 37°C. The change in absorbance at 405 nm was determined with a Titertek plate reader.

For peptidase activities, cultures were grown in semidefined medium. Peptidase activity was determined by measuring the release of leucine from Leu-Pro as described by van Boven et al. (49). The reaction mixture contained cell extract, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), horseradish peroxidase (0.5 mg ml−1), l-amino acid oxidase (0.5 mg ml−1), and o-dianisidine (0.18 mg ml−1). The reaction was started by the addition of 2.5 mM Leu-Pro, and hydrolysis was monitored in a microtiter tray at 492 nm.

Determination of glucose concentration.

The concentration of glucose in culture supernatants was determined by glucose oxidase assays, using a glucose diagnostic kit (Sigma).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequence shown in Fig. 1B has been assigned GenBank accession no. AF014460.

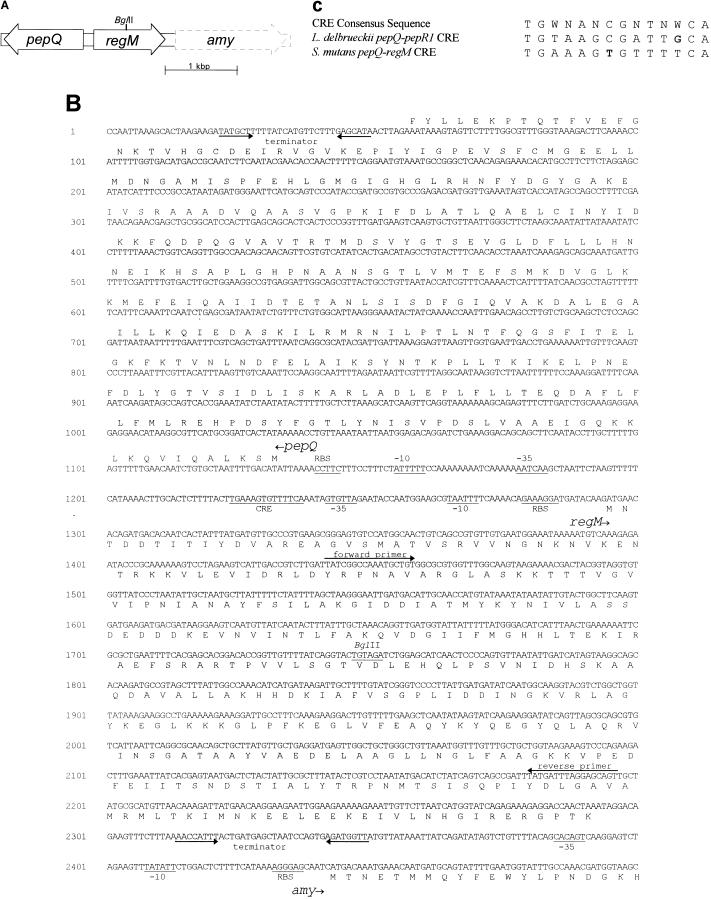

FIG. 1.

Sequence analysis of the regM locus. (A) Genetic organization of the regM region in S. mutans on the basis of nucleotide sequence analysis. The BglII site used to inactivate the regM gene by insertion of a tetracycline resistance cassette is indicated. (B) The nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences of pepQ and regM. Potential ribosome binding sites (RBS), −10 and −35 promoter elements, and terminators are indicated. A 14-bp sequence with homology to the CRE consensus sequence is underlined. The sites of the primers used in the PCR amplification of an internal region of regM are indicated by arrows. The BglII site used for insertional inactivation is also indicated. (C) Potential CRE sequences from within the promoter regions of L. delbrueckii subsp. lactis pepQ and pepR1 (43) and S. mutans LT11 pepQ and regM genes. The sequences differ from the consensus CRE sequence defined by Weickert and Chambliss (50) at one position, indicated in boldface.

RESULTS

Cloning of a ccpA-like gene.

PCR using degenerate primers based on the sequence of known ccpA sequences was used to isolate a homologous gene from S. mutans LT11. The CcpA sequences of B. subtilis (11), B. megaterium (16), Clostridium acetobutylicum (4), and Lactobacillus casei (GenBank accession no. U28137) were aligned, and several sets of oligonucleotide primers were designed from areas of high homology. Only one pair successfully amplified a PCR product with homology to ccpA: 5′-TA(CT)CG(GT)CC(AT)AA(CT)GC(AG) GT-3′, complementary to positions 468 to 484 of B. subtilis ccpA; and 5′-AC(GTC)GC(AG)CC(AG)ATATCATA-3′, complementary to positions 1214 to 1231 of B. subtilis ccpA. The DNA fragment of approximately 800 bp was cloned into pGEM-T. The cloned PCR product was sequenced in one direction; the deduced amino acid sequence of 167 residues had 53% amino acid identity with the ccpA of B. subtilis. Because of its involvement in regulation (see below), the gene carrying the cloned fragment from S. mutans was designated regM.

The cloned PCR fragment was used as a probe to screen the S. mutans Lambda ZAP Express gene bank. Approximately 3,000 plaques were screened, resulting in detection of 11 hybridizing plaques; 4 plaques were selected for further analysis. Phagemids carrying inserts were excised from the phage, and restriction mapping confirmed that the plasmids had overlapping inserts ranging from 3.5 to 5.5 kbp. Restriction mapping and partial sequencing confirmed that three of the excised plasmids (pOB208, pOB209, and pOB215) contained the regM gene in its entirety whereas the other plasmid (pOB210) contained the C-terminal region of regM. The three clones covered a region of approximately 7 kbp of the S. mutans LT11 chromosome. From the mapped restriction sites, subclones were constructed from the three plasmids for nucleotide sequencing.

Sequence analysis of the regM gene.

The nucleotide sequence of the regM gene was 1,002 bp in length and was preceded by a putative ribosome binding site (AAGGA) located 10 bp upstream of a methionine codon. A potential promoter was also identified, with a −10 (TAATTT) sequence at base 1265 and a −35 (GTGTTA) at base 1242 (Fig. 1).

The deduced amino acid sequence defined a protein of 333 amino acids with a calculated molecular weight of 36,606. A protein of this size was detected in whole-cell extracts of S. mutans and E. coli pOB208 by Western blot analysis with anti-B. megaterium CcpA (data not shown). The deduced protein sequence had a high degree of similarity to known and putative CcpA proteins of other organisms as well as to other regulators (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Comparison of deduced amino acid sequences with homology to S. mutans RegM

| Bacterium | Gene | No. of amino acid residues | % Amino acid identity | Function | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Streptococcus mutans | regM | 333 | 100 | This work | This work |

| S. pyogenes | NDa | 333 | 90 | ND | 29 |

| Lactobacillus casei | ccpA | 332 | 61 | ND | U28137b |

| L. pentosus | ccpA | 287 | 60 | ND | Z80342b |

| Bacillus subtilis | ccpA | 334 | 53 | Catabolite control protein | 11 |

| B. megaterium | ccpA | 332 | 52 | Catabolite control protein | 16 |

| L. delbrueckii subsp. lactis | pepR1 | 333 | 49 | Activator of PepQ | 43 |

| Staphylococcus xylosus | ccpA | 329 | 47 | Catabolite control protein | 6 |

| Clostridium acetobutylicum | regA | 324 | 38 | Regulator of starch metabolism | 4 |

ND, not described.

GenBank accession number.

Sequence analysis of flanking genes.

The 1,282-bp open reading frame (ORF) immediately upstream of regM lay on the opposite strand and is preceded by a putative ribosome binding site (GAAGG) located 7 bp upstream. The potential promoter for this gene had a −10 (AAAAAT) sequence at base 1160 and a −35 (TTGATT) at base 1183 (Fig. 1). A potential terminator with a free energy value of −3.2 kcal centered on base 36 was also identified.

The ORF encodes a protein of 359 amino acids with a calculated molecular weight of 38,812. The deduced protein is homologous to the PepQ of Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. lactis (43% amino acid identity [42]). A 14-bp palindromic sequence, differing by 1 bp from the CRE consensus sequence (15), lies within the intergenic region between regM and pepQ (Fig. 1C). This gene arrangement is identical to that of the pepQ and pepR1 genes of L. delbrueckii subsp. lactis, where the CcpA homolog, PepR1, has been hypothesized to be an activator of PepQ (43).

The ORF downstream of regM encoding an amylase (40) has the same polarity as regM, with 150 bp between them. It has its own promoter, and there is no evidence for cotranscription with the regM gene. A potential terminator of regM with a free energy value of −4.4 kcal was identified between the genes. The amy gene is not preceded by a CRE sequence.

Inactivation of regM.

To determine the function of RegM in S. mutans, the regM gene was interrupted by the insertion of a tetracycline resistance cassette as described in Materials and Methods. The insertion was confirmed by Southern blot analysis, and the loss of the cross-reactive protein was demonstrated after SDS-PAGE by Western blot analysis with anti-B. megaterium CcpA (data not shown).

Effects of RegM on catabolite repression of enzyme activities.

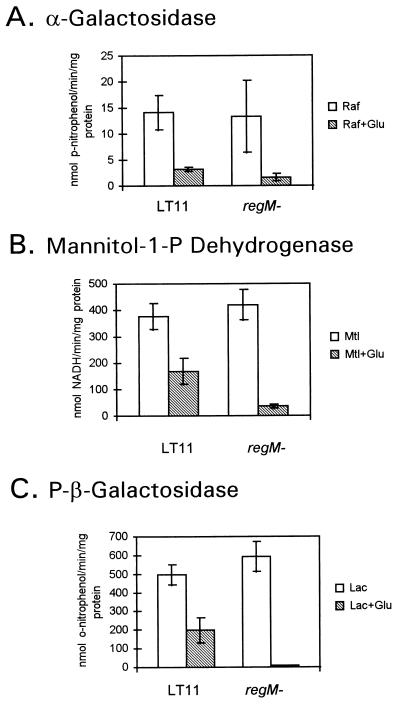

Effects of the loss of RegM on catabolite repression of three enzyme activities were determined. Activities for α-galactosidase, mannitol-1-P dehydrogenase, and P-β-galactosidase were detected in overnight cultures of S. mutans LT11 grown in THYE in the presence of the inducing sugar (Fig. 2). To test for catabolite repression, glucose was included in the medium, and this resulted in a reduction of all enzyme activities in the wild-type strain (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Enzyme activities of the S. mutans LT11 wild type and regM mutant after overnight growth in THYE plus 0.5% inducing sugar and THYE plus 0.5% inducing sugar and 0.5% glucose (Glu). The inducing sugars were raffinose (Raf), mannitol (Mtl), and lactose (Lac). Results are averages of three independent experiments, with standard deviations indicated by error bars.

The same enzyme assays were performed with the regM mutant. In the presence of the appropriate inducing sugar, α-galactosidase, mannitol-1-P dehydrogenase, and P-β-galactosidase activities were all expressed by the regM mutant at the same level as by the wild type. However, the addition of glucose resulted in a stronger repression of all three enzyme activities than in the wild-type strain (Fig. 2).

Diauxic growth curves.

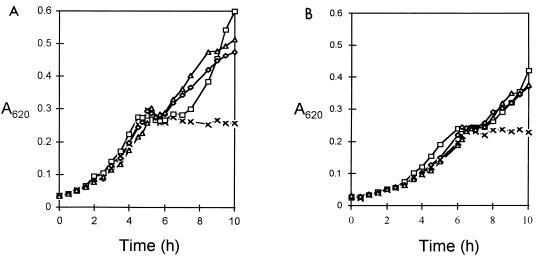

To determine whether loss of RegM affected the utilization of carbohydrates, growth of the wild-type S. mutans LT11 on sugars in the presence of glucose was compared to that of the regM mutant (Fig. 3). The regM mutant exhibited a slight reduction of growth rates on all substrates compared to the wild type.

FIG. 3.

Growth of S. mutans LT11 (A) and the regM mutant (B) on glucose (X), glucose plus lactose (□), glucose plus mannitol (◊), and glucose plus raffinose (▵).

Diauxic growth curves were obtained when the wild-type S. mutans LT11 was grown on cellobiose, galactose, lactose, mannitol, melibiose, raffinose, salicin, or sorbitol in the presence of glucose, indicating catabolite repression of the enzymes responsible for utilization of these sugars. No diauxic growth was apparent when the wild type was grown on maltose or trehalose with the addition of glucose.

The regM mutant displayed diauxic growth on the same sugars as the wild type, indicating that the enzymes responsible for utilization of cellobiose, galactose, lactose, mannitol, melibiose, raffinose, salicin, and sorbitol were still catabolite repressed by glucose even in the absence of RegM.

Inactivation of pepQ.

Sequence similarity suggested that the PepQ activity of S. mutans is similar to that of the PepQ of L. delbrueckii subsp. lactis, which has been classified as an X-Pro dipeptidase (42). To determine whether the S. mutans PepQ is also an X-Pro dipeptidase, the pepQ gene was interrupted by the insertion of pVA8912. The activity of PepQ was confirmed by peptidase assays, which indicated that the S. mutans wild type produced a peptidase able to cleave Leu-Pro whereas the pepQ mutant had lost this ability. This result also indicated that no other peptidase expressed by S. mutans has activity against Leu-Pro.

To confirm the action of this peptidase in cleaving Leu-Pro, the pepQ mutation was introduced into the S. mutans proline auxotroph, Pro-1. This auxotroph was obtained by Procino et al. (28) after introduction of the streptococcal transposon Tn916 into S. mutans GS-5. Pro-1 was unable to grow on semidefined media without proline; however it did grow on media where proline was replaced with the dipeptide, Leu-Pro. When pepQ was insertionally inactivated in the proline auxotroph, the resultant double mutant was no longer able to grow on Leu-Pro, showing that the Leu-Pro dipeptidase is required for growth of Pro-1 in the absence of proline.

Effect of RegM on PepQ activity.

The CcpA homolog in L. delbrueckii subsp. lactis, PepR1, has been suggested to be an activator of PepQ activity (43). To determine if this was the case in S. mutans, growth and PepQ activities of the wild type and regM mutant were compared. S. mutans LT11 was grown in semidefined media with and without proline and in media where proline was replaced with the dipeptide Leu-Pro. Peptidase activities of cells harvested in exponential and stationary phases confirmed that PepQ was constitutively expressed, with no induction of the peptidase in the presence of Leu-Pro.

The regM mutant also constitutively expressed PepQ, with no evidence of Leu-Pro acting as an inducer of peptidase activity. Peptidase levels were similar in the regM mutant and the wild type; thus, there was no evidence that RegM was involved in the regulation of PepQ.

Inactivation of pepQ has no apparent effect on growth of S. mutans in minimal medium, even when Leu-Pro is the only source of proline. In contrast, the proline auxotroph Pro-1 has an absolute requirement for PepQ in the absence of free proline; thus, any alterations in PepQ activity will influence the growth of this mutant. To determine if RegM has any effect on PepQ activity in the proline auxotroph, growth and PepQ activities of Pro-1 and a regM mutant of Pro-1 were compared. Southern blot analysis and PCR confirmed that genetic arrangement of pepQ and regM in S. mutans GS-5 and its proline auxotroph Pro-1 was the same as in S. mutans LT11. As Pro-1 carries Tn916, it is tetracycline resistant. Therefore, regM was inactivated by the insertion of pVA8912, which confers erythromycin resistance. The PepQ activities of Pro-1 and the double mutant were not altered in the presence of Leu-Pro; thus, although the loss of RegM in the Pro-1 mutant led to either increases in the lag time before growth on Leu-Pro or slower growth rates, determination of PepQ activities did not reveal any evidence for regulation by RegM.

DISCUSSION

The ccpA gene has been identified as one coding for a catabolite control protein in B. subtilis (11), B. megaterium (17), and Staphylococcus xylosus (6). Loss of CcpA in these organisms results in relief of catabolite repression of a number of enzyme activities, leading to the hypothesis that CcpA-dependent catabolite repression is a common mechanism employed by gram-positive bacteria (36). In this study, we cloned an S. mutans gene homologous to ccpA and found that its product is not essential for catabolite repression of enzymes responsible for the utilization of a number of carbohydrates.

The deduced amino acid sequence of S. mutans RegM is homologous to sequences of CcpA proteins of other organisms (Table 2), and in common with these proteins, the N-terminal portion contains the DNA binding region consensus sequence of the LacI-GalR-type transcription factors (26). The regM gene of S. mutans is flanked by a gene encoding the dipeptidase PepQ on the opposite strand upstream and an amy gene downstream. The two ORFs with homology to motA and motB downstream of ccpA of B. subtilis and B. megaterium (9, 16) were not found adjacent to regM in S. mutans. This is also the situation in S. xylosus, where the ORFs downstream of ccpA encode proteins probably involved in acetone and butane-diol utilization (6). The ORFs homologous to motAB, although predicted to be cotranscribed with ccpA, are thought to have no role in catabolite repression in B. subtilis and B. megaterium (14). Thus, ccpA-like genes are found in a variety of genetic environments, suggesting that flanking genes do not play a role in catabolite repression.

The selective use of sugars by catabolite repression can be demonstrated by a diauxic growth curve where the preferred sugar is consumed first, generally with a lag phase before consumption of the secondary sugar. To determine if RegM has a role in the regulation of diauxic growth and catabolic enzyme activities, a mutant in which the regM gene was disrupted by insertion of a tetracycline resistance cassette was constructed. Diauxic growth of S. mutans on a number of sugars was not affected by the loss of RegM. This is in contrast to the ccpA strain of B. megaterium, which no longer exhibited diauxic growth on xylose in the presence of glucose, indicating relief from catabolite repression (39).

Insertional inactivation of regM in S. mutans did not relieve catabolite repression of α-galactosidase, mannitol-1-P dehydrogenase, or P-β-galactosidase activity, nor was glucose repression of starch-clearing activity on agar plates relieved by loss of RegM (data not shown). A recent study has also reported that inactivation of ccpA in L. casei did not relieve glucose repression of P-β-galactosidase activity (8). In contrast to studies in other organisms, where loss of CcpA resulted in relief of catabolite repression of some enzyme activities, the mutation in S. mutans led to increased glucose repression of the enzymes under study. Thus, while RegM clearly interacts in some way in catabolite repression, its role is unclear.

There is increasing evidence that catabolite repression of several enzyme activities in B. subtilis is more complex than the initial CcpA model suggests, with more than one mechanism of repression involved. Catabolite repression of bglPH expression in B. subtilis has been reported to occur by two different mechanisms (20). One mechanism involves CcpA and HPr, but a CRE-CcpA-independent form of catabolite repression involving a third protein, the antiterminator LicT, has also been reported (20). The proposed mechanism also involves HPr, which activates LicT when phosphorylated at His-15. Second mechanisms of catabolite repression of the levanase and xylose operons of B. subtilis involving their regulator proteins have also been demonstrated (19, 24). The LevR activator protein is positively controlled by HPr-His-P (44). Although more than one form of catabolite repression operates in these systems, the loss of CcpA results in at least partial relief of catabolite repression by glucose. This is in contrast to the increased repression of catabolic enzymatic activities in the S. mutans regM mutant. It therefore seems possible that catabolite repression involves competitive interactions between RegM and one or more as yet unidentified other factors, probably including HPr in phosphorylated or unphosphorylated form.

The operons encoding α-galactosidase and P-β-galactosidase activities in S. mutans are preceded by regulatory genes, and it is possible that these genes encode proteins with roles in catabolite repression similar to those of the XylR and LevR regulatory components in B. subtilis. However, the components of the operon encoding mannitol-1-P dehydrogenase have not yet been fully determined, and regulatory elements remain unknown (13).

CRE sequences have been identified within the operons encoding α-galactosidase and mannitol-1-P dehydrogenase (15). A CRE sequence lies within the promoter region which precedes the gene encoding α-galactosidase, the first gene of the msm operon (32). Although a CRE sequence has been found near the start of the mannitol-P dehydrogenase gene, mtlD (15), this is not the first gene of the operon and so does not fit the definition of a CRE introduced by Hueck et al. (15). The promoter region of the operon encoding mannitol-1-P dehydrogenase has not yet been described (13), and so the presence of CREs cannot be determined. Although S. mutans α-amylase and the lactose operon encoding P-β-galactosidase (30) are subject to catabolite repression by glucose, CRE sequences could not be identified by the method of Hueck et al. (i.e., one mismatch to the consensus sequence within 200 bp of the translation start [15]). Nevertheless, α-galactosidase, mannitol-1-P dehydrogenase and P-β-galactosidase were all affected by loss of RegM in S. mutans, suggesting either that CRE is not the binding site of a repressor protein or that CREs which do not match the consensus sequence exist. The consensus sequence of CREs may need to be redefined, as was demonstrated by the recent identification of a CRE sequence containing an extra base in the levanase operon of B. subtilis (24); this operon was previously classified by Hueck et al. (15) as not containing a relevant CRE sequence.

The genetic arrangement of S. mutans pepQ and regM genes is identical to that of the homologous genes in L. delbrueckii subsp. lactis. In this organism, PepR1, the CcpA homolog, was postulated to be an activator of PepQ expression, as it activated the expression of a pepQ-β-gal fusion in E. coli by a factor of 1.6 (43). This activation factor is quite low and could not be confirmed by the experimental evidence in this work, with PepQ activity constitutively expressed in S. mutans and loss of RegM having no apparent effect on assayed activity or growth of the RegM mutant. However, although the loss of RegM in a proline auxotroph led to no apparent change in PepQ activity, growth characteristics of the double mutant in the absence of free proline were altered. As the peptidase activity is required for growth of S. mutans in these circumstances, a reduction in the rate of expression may explain these alterations. Activation of peptidase activities in other species has previously been demonstrated in response to stationary phase (PepT of B. subtilis [38]), anaerobiosis (PepT of Salmonella typhimurium [41]), and lack of phosphate (PepD of E. coli [12]). In S. typhimurium, PepE has been shown to be regulated by the cAMP receptor protein, which is involved in catabolite repression in gram-negative bacteria (2), and this represents a link between carbohydrate and protein metabolism. The observation that a ccpA mutant of B. subtilis is unable to grow on minimal medium containing only glucose and ammonium may also indicate such a connection between regulation of carbon and nitrogen metabolism (51).

On the basis of amino acid identity, the RegM of S. mutans is clearly a member of the family of regulatory proteins including CcpA (26) (Table 2). This family of proteins may have a variety of functions—the RegA protein of C. acetobutylicum is a regulator of α-amylase but is not involved in its catabolite repression (4). The role of CcpA in L. casei has not been determined, although it is thought to have some involvement in catabolite repression (8). The functions of putative CcpA proteins of S. pyogenes and L. pentosus have not been described to our knowledge. It may transpire that some of these putative CcpA proteins play more general regulatory roles and are not necessarily responsible for catabolite repression.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank L. Daneo-Moore for providing S. mutans Pro-1 and E. Küster for providing antiserum to B. megaterium CcpA.

This work was supported by Medical Research Council grant G9505672PB.

REFERENCES

- 1.Colby S M, Russell R R B. Sugar metabolism by mutans streptococci. J Appl Microbiol Symp Suppl. 1997;83:80S–88S. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.83.s1.9.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Conlin C A, Håkensson K, Lilias A, Miller C G. Cloning and nucleotide sequence of the cyclic AMP receptor protein-regulated Salmonella typhimurium pepE gene and crystallization of its product, an α-aspartyl dipeptidase. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:166–172. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.1.166-172.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cvitkovitch D G, Boyd D A, Hamilton I R. Regulation of sugar transport via the multiple sugar metabolism operon of Streptococcus mutans by the phosphoenolpyruvate phosphotransferase system. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:5704–5706. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.19.5704-5706.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davison S P, Santangelo J D, Reid S J, Woods D R. A Clostridium acetobutylicum regulator gene (regA) affecting amylase production in Bacillus subtilis. Microbiology. 1995;141:989–996. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-4-989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deutscher J, Küster E, Bergstedt U, Charrier V, Hillen W. Protein kinase-dependent HPr/CcpA interaction links glycolytic activity to carbon catabolite repression in Gram-positive bacteria. Mol Microbiol. 1995;15:1049–1053. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Egeter O, Brückner R. Catabolite repression mediated by the catabolite control protein CcpA in Staphylococcus xylosus. Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:739–749. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.301398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fujita Y, Miwa Y, Galinier A, Deutscher J. Specific recognition of the Bacillus subtilis gnt cis-acting catabolite-responsive element by a protein complex formed between CcpA and seryl-phosphorylated HPr. Mol Microbiol. 1995;17:953–960. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_17050953.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gosalbes M J, Monedero V, Alpert C-A, Pérez-Martínez G. Establishing a model to study the regulation of the lactose operon in Lactobacillus casei. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;148:83–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb10271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grundy F J, Waters D A, Takova T Y, Henkin T M. Identification of genes involved in utilization of acetate and acetoin in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 1993;10:259–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01952.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harrington D J, Russell R R B. Multiple changes in cell wall antigens of isogenic mutants of Streptococcus mutans. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:5925–5933. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.18.5925-5933.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henkin T M, Grundy F J, Nicholson W L, Chambliss G H. Catabolite repression of α-amylase gene expression in Bacillus subtilis involves a trans-acting gene product homologous to the Escherichia coli lacI and galR repressors. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:575–584. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb00728.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henrich B, Backes H, Klein J R, Plapp R. The promoter region of the Escherichia coli pepD gene: deletion analysis and control by phosphate concentration. Mol Gen Genet. 1992;232:117–125. doi: 10.1007/BF00299144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Honeyman A L, Curtiss R., III Isolation, characterization and nucleotide sequence, of the Streptococcus mutans mannitol-phosphate dehydrogenase gene and the mannitol-specific factor III gene of the phosphoenolpyruvate phosphotransferase system. Infect Immun. 1992;60:3369–3375. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.8.3369-3375.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hueck C J, Hillen W. Catabolite repression in Bacillus subtilis: a global regulatory mechanism for the Gram-positive bacteria? Mol Microbiol. 1995;15:395–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hueck C J, Hillen W, Saier M H., Jr Analysis of a cis-active sequence mediating catabolite repression in Gram-positive bacteria. Res Microbiol. 1994;145:503–518. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(94)90028-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hueck C, Kraus A, Hillen W. Sequences of ccpA and two downstream Bacillus megaterium genes with homology to the motAB operon from Bacillus subtilis. Gene. 1994;143:147–148. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90621-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hueck C J, Kraus A, Schmiedel D, Hillen W. Cloning, expression and functional analyses of the catabolite control protein CcpA from Bacillus megaterium. Mol Microbiol. 1995;16:855–864. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim H J, Guvener Z T, Cho J Y, Chung K-C, Chambliss G H. Specificity of DNA binding activity of the Bacillus subtilis catabolite control protein CcpA. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:5129–5134. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.17.5129-5134.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kraus A, Hueck C, Gärtner D, Hillen W. Catabolite repression of the Bacillus subtilis xyl operon involves a cis element functional in the context of an unrelated sequence, and glucose exerts additional xylR-dependent repression. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:1738–1745. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.6.1738-1745.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krüger S, Gertz S, Hecker M. Transcriptional analysis of bglPH expression in Bacillus subtilis: evidence for two distinct pathways mediating carbon catabolite repression. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2637–2644. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.9.2637-2644.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Küster E, Luesink E J, de Vos W M, Hillen W. Immunological crossreactivity to the catabolite control protein CcpA from Bacillus megaterium is found in many Gram-positive bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;139:109–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liberman E S, Bleiweis A S. Role of the phosphoenolpyruvate-dependent glucose phosphotransferase system of Streptococcus mutans GS5 in the regulation of lactose uptake. Infect Immun. 1984;43:536–542. doi: 10.1128/iai.43.2.536-542.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Malke H, Mechold U, Gase K, Gerlach D. Inactivation of the streptokinase gene prevents Streptococcus equisimilis H46A from acquiring cell-associated plasmin activity in the presence of plasminogen. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;116:107–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb06683.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martin-Verstraete I, Stülke J, Klier A, Rapoport G. Two different mechanisms mediate catabolite repression of the Bacillus subtilis levanase operon. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:6919–6927. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.23.6919-6927.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McLaughlin R E, Ferretti J J. Electrotransformation of streptococci. Methods Mol Biol. 1995;47:185–193. doi: 10.1385/0-89603-310-4:185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nguyen C C, Saier M H., Jr Phylogenetic, structural and functional analyses of the LacI-GalR family of bacterial transcription factors. FEBS Lett. 1995;377:98–102. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)01344-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perry D, Kuramitsu H K. Genetic linkage among cloned genes in Streptococcus mutans. Infect Immun. 1989;57:805–809. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.3.805-809.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Procino J K, Marri L, Shockman G D, Daneo-Moore L. Tn916 insertional inactivation of multiple genes on the chromosome of Streptococcus mutans GS-5. Infect Immun. 1988;56:2866–2870. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.11.2866-2870.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roe, B. A., S. Clifton, M. McShan, and J. J. Ferretti. Streptococcal genome sequencing project. http://dna1.chem.uoknor.edu/strep.html.

- 30.Rosey E L, Stewart G C. Nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences of the lacR, lacABCD, and lacFE genes encoding the repressor, tagatose 6-phosphate gene cluster, and sugar-specific phosphotransferase system components of the lactose operon of Streptococcus mutans. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:6159–6170. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.19.6159-6170.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Russell R R B. Purification of Streptococcus mutans glucosyltransferase by polyethylene glycol precipitation. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1979;6:197–199. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Russell R R B, Aduse-Opoku J, Sutcliffe I C, Tao L, Ferretti J J. A binding protein-dependent transport system in Streptococcus mutans responsible for multiple sugar metabolism. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:4631–4637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Russell R R B, Ferretti J J. Nucleotide sequence of the dextran glucosidase (dexB) gene of Streptococcus mutans. J Gen Microbiol. 1990;136:803–810. doi: 10.1099/00221287-136-5-803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Russell R R B, Smith K J. Effect of subculturing on location of Streptococcus mutans antigens. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1986;35:319–323. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saier M H., Jr Cyclic AMP-independent catabolite repression in bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;138:97–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saier M H, Jr, Chauvaux S, Cook G M, Deutscher J, Paulsen I T, Reizer J, Ye J-J. Catabolite repression and inducer control in Gram-positive bacteria. Microbiology. 1996;142:217–230. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-2-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schrögel O, Krispin O, Allmansberger R. Expression of a pepT homologue from Bacillus subtilis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;145:341–348. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08598.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schmiedel D, Hillen W. Contributions of XylR, CcpA and cre to diauxic growth of Bacillus megaterium and to xylose isomerase expression in the presence of glucose and xylose. Mol Gen Genet. 1996;250:259–266. doi: 10.1007/BF02174383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Simpson, C. L., and R. R. B. Russell. Unpublished data.

- 41.Strauch K L, Lenk J B, Gamble B L, Miller C G. Oxygen regulation in Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1985;161:673–680. doi: 10.1128/jb.161.2.673-680.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stucky K, Klein J R, Schüller A, Matern H, Henrich B, Plapp R. Cloning and DNA sequence analysis of pepQ, a prolidase gene from Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. lactis DSM7290 and partial characterization of its product. Mol Gen Genet. 1995;247:494–500. doi: 10.1007/BF00293152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stucky K, Schick J, Klein J R, Henrich B, Plapp R. Characterization of pepR1, a gene coding for a potential transcriptional regulator of Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. lactis DSM7290. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;136:63–69. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(95)00494-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stülke J, Martin-Verstraete I, Charrier V, Klier A, Deutscher J, Rapoport G. The HPr protein of the phosphotransferase system links induction and catabolite repression of the Bacillus subtilis levanase operon. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:6928–6936. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.23.6928-6936.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tao L, MacAlister T J, Tanzer J M. Transformation efficiency of EMS-induced mutants of Streptococcus mutans of altered cell shape. J Dent Res. 1993;72:1032–1039. doi: 10.1177/00220345930720060701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Terleckyj B, Willett P N, Shockman G D. Growth of several cariogenic strains of oral streptococci in a chemically defined medium. Infect Immun. 1975;11:649–655. doi: 10.1128/iai.11.4.649-655.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ushiro I, Lumb S M, Aduse-Opoku J, Ferretti J J, Russell R R B. Chromosomal deletions in melibiose-negative isolates of Streptococcus mutans. J Dent Res. 1991;70:1422–1426. doi: 10.1177/00220345910700110501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vadeboncoeur C, Pelletier M. The phosphoenolpyruvate:sugar phosphotransferase system of oral streptococci and its role in the control of sugar metabolism. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1997;19:187–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1997.tb00297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.van Boven A, Tan P S T, Konings W N. Purification and characterization of a dipeptidase from Streptococcus cremoris Wg2. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1988;54:43–49. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.1.43-49.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weickert M J, Chambliss G H. Site-directed mutagenesis of a catabolite repression operator sequence in Bacillus subtilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:6238–6242. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.16.6238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wray L V, Jr, Pettengill F K, Fisher S H. Catabolite repression of the Bacillus subtilis hut operon requires a cis-acting site located downstream of the transcription initiation site. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:1894–1902. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.7.1894-1902.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]