Abstract

Oxidative stress (OS) impairs organic function and is considered causally related to cellular senescence and death. This study aims to evaluate if the redox balance varies in relation to age and gender in healthy cats. To quantify the oxidative status of this species we determined the oxidative damage as serum reactive oxygen metabolites (ROM) and the total serum antioxidant capacity (SAC). In addition, we used the ratio of ROM to SAC as a measure of the oxidative balance, with higher values meaning higher oxidative stress (oxidative stress index). Our results suggest that the male population is at oxidative risk when compared with females, especially between the age of 2 and 7 years. Nutritional strategies in this population looking for additional antioxidant support would probably avoid the oxidative stress status that predisposes to chronic processes in senior male cats. Further clinical trials in this field are recommended.

Short Communication

There is growing evidence that oxidative stress (OS) is considered causally related to cellular senescence and death. Organisms cope with oxidant production by means of antioxidant enzymes and molecules, many of which are derived from the diet (eg, vitamins and carotenoids). The balance between oxidants and antioxidant defences determines the degree of OS, which is related closely to ageing, life span and health. 1

In veterinary medicine, typical changes associated with ageing have been studied mainly in dogs, and very often results obtained were transferred to cats. However, neither the physiology nor metabolism of a species must be assumed by another because their circumstances are different, and this is no exception.

This study aims to evaluate if the redox balance varies in relation to age and gender in cats. To quantify the oxidative status of this species, we determined (i) the oxidative damage as serum reactive oxygen substances (ROS) and (ii) the total serum antioxidant capacity (SAC). Additionally, we used the ratio of ROS to SAC as a measure of the oxidative balance, with higher values indicating higher oxidative stress index (OSi). This parameter has been previously used in humans 2 and other species, 3 demonstrating that OSi shows the oxidative status of the animals more accurately than isolated ROS and SAC interpretation.

To our knowledge, this is the first study that quantifies OS in healthy cats.

The study population consisted of 38 healthy, client-owned cats from Lugo (northwest Spain) and the surrounding areas that lived indoors and not in houses with gardens or in cottages. No breed or castrated/neutered restrictions were made although we note that all males were neutered and only seven of the females were non-castrated. Taking into account the whole population, animals were divided in different age groups, depending on the statistical analysis performed: comparisons depending on age (A) were made taking into account two groups — those between 2 and 7 years old (A-1, n = 23), and those between >7 and 13 years old (A-2, n = 15). This criterion was made considering the recommendations of the Feline Advisory Bureau. 4 The same population was also divided depending on gender (G): females (FEM, n = 22) and males (MAL, n = 16).

For interactions A×G, the A-2 group was also divided into two more accurate groups: those between >7 and 10 years old (mature cats, n = 8) and those between >10 and 13 years old (senior cats, n = 7). The latter group included only females because we did not find clinically healthy males that could be incorporated into the study.

Animals presenting any clinical signs of disease or those receiving any type of medication were excluded. Each animal’s health condition was assessed by a complete physical examination according to last World Small Animal Veterinary Association (WSAVA) recommendations. 5

All cats received the same kind of diet, consisting in commercial cat food adapted to the age of the animal, without special requests. Body condition score was measured according to the 1–9 WSAVA point-scale 5 showing a mean range of around 4–6 years, independently of sex and age. Sanitary management was uniform among cats, with all animals being helminth free and immunised periodically.

The animals fasted for 12 h prior to the collection of the blood samples. These were collected by venipuncture in the right or left cephalic vein. After collection, blood samples were centrifuged immediately at 1500 g for 10 mins. The serum obtained was divided into aliquots that were stored in plastic flasks resistant to freezing and stored at −20ºC until processing within the first 3 months of collection.

The determinable reactive oxygen metabolites were quantified as an indicator of ROS 6 for which the d-ROMs Test (Diacron International) was used. This test determines hydroperoxides, which are breakdown products of lipids, as well as of other organic substrates. Results are expressed as Carratelli Units (CarrU), where 1 CarrU = 0.08 mg H2O2/dl. 7 The SAC was estimated by the quantification of the plasma barrier to oxidation with the OXY-Adsorbent Test (Diacron International). SAC is expressed as µmol HClO/ml.

The OSi was calculated as ROS/SAC, expressed as CarrU/(µmol HClO/ml). Thus, increase in the ratio indicates risk of OS due to increase in ROS production or defensive antioxidant consumption. 3

Both ROS and SAC were measured on an ultraviolet/visible absorption spectrophotometer (Clima MC-15; RAL Técnica para el Laboratorio).

Statistical analysis was performed using commercial software (IBM SPSS Statistics 19.0 for Windows). Normally distributed data were expressed as mean values ± standard error (SE). On the basis of data normality, as assessed by Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, Student’s t-tests were used to compare redox status (d-ROM, SAC and OSi values) between groups of age (A-1 versus A-2), between sexes (FEM versus MAL) and within the FEM group between neutered and non-neutered individuals. Equality of variance for the variables tested was assessed with Levene’s test. Interaction between age and gender was made using the Univariant ANOVA method and the Bonferroni’s corrections to establish statistical differences between groups. For all tests, P≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Data obtained from oxidants–antioxidants balance, depending separately on age and gender are shown in Tables 1 and 2, respectively, as mean ± SE and the corresponding minimum and maximum values together with the P-value.

Table 1.

Mean values [± standard error (SE)] of redox balance in cats from this study grouped by age

| Parameter | Group (age, years) | Mean (± SE) | P | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| d-ROM CarrU | 2–7 | 155.9 ± 13.2 | 0.046 | 90.6 | 282.0 |

| >7 and <12 | 126.4 ± 7.6 | 72.0 | 210.1 | ||

| SAC μmol HClO/ml | 2–7 | 384.2 ± 25.1 | 0.166 | 269.5 | 664.9 |

| >7 and <12 | 346.8 ± 13.9 | 273.4 | 575.1 | ||

| OSi | 2–7 | 0.43 ± 0.02 | 0.223 | 0.19 | 0.90 |

| >7 and <12 | 0.37 ± 0.04 | 0.23 | 0.73 |

OSi = oxidative stress index; SAC = serum antioxidant capacity

Table 2.

Mean values [± standard error (SE)] of redox balance in cats from this study grouped by gender

| Parameter | Group | Mean (± SE) | Student’s t-test | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| d-ROM CarrU | FEM | 123.0 ± 6.7 | 0.013 | 78.0 | 184.3 |

| MAL | 158.8 ± 13.2 | 72.0 | 282.0 | ||

| SAC μmol HClO/ml | FEM | 350.2 ± 15.6 | 0.315 | 269.5 | 575.1 |

| MAL | 377.2 ± 22.7 | 288.3 | 664.9 | ||

| OSi | FEM | 0.36 ± 0.02 | 0.060 | 0.23 | 0.47 |

| MAL | 0.44 ± 0.04 | 0.19 | 0.90 |

FEM = female; MAL = male; OSi = oxidative stress index; SAC = serum antioxidant capacity

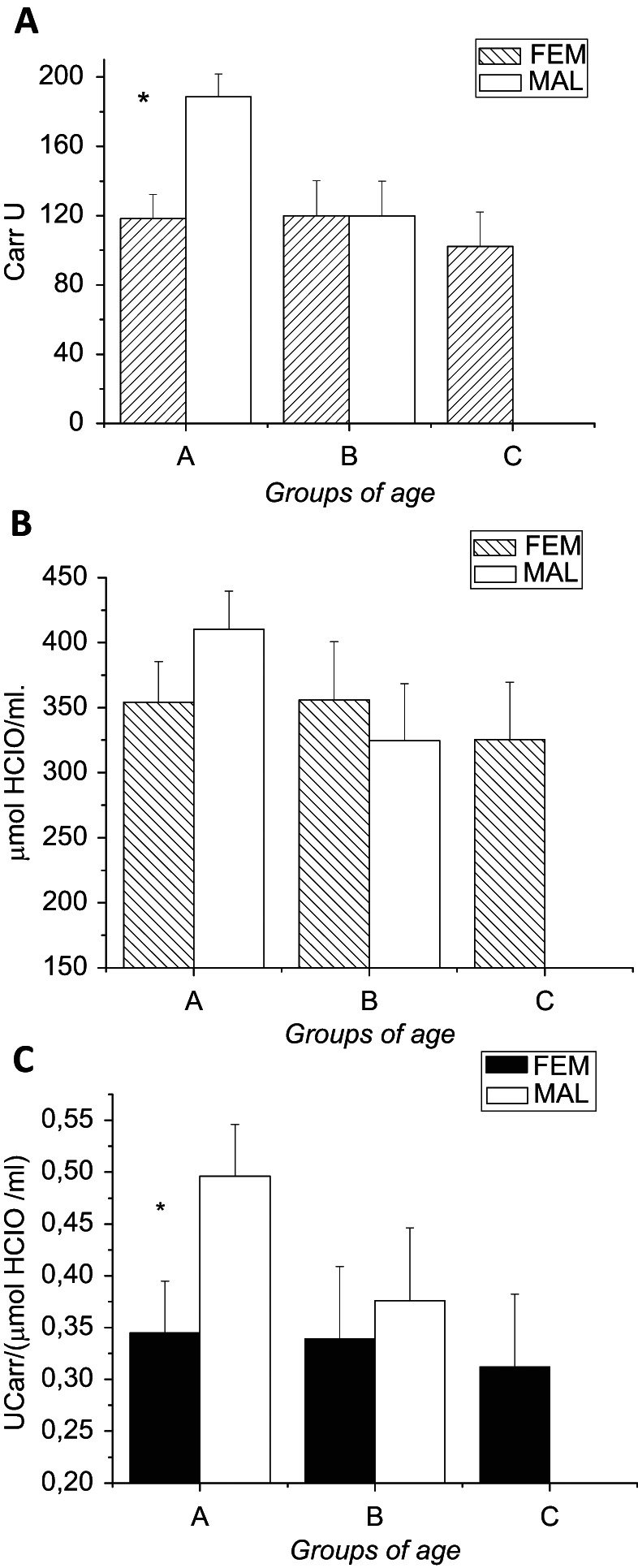

Taking into account age classification, differences (P ≤0.05) were found in d-ROM values: mature/senior cats (>7 and <13 years old) had less oxidant burden than younger ones (2–≤7 years old). Nevertheless, no differences were observed in the antioxidant defence (SAC) or the general redox balance (OSi ratio) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Interaction (age × gender) in the cats of our study. (a) d-ROM values; (b) serum antioxidant capacity (SAC) values; (c) oxidative stress index (OSi) ratio. *Differences between groups (P ≤0.05)

Considering gender classification, differences (P ≤0.05) were found also in d-ROM values: now males had higher oxidant burden than females, with no differences in the antioxidant defence. Balance between oxidant and antioxidant elements (OSi) tended (P<0.1) to indicate higher OS risk in males than in females. Considering neutering status in the FEM group, no statistical differences were observed between groups in the three studied parameters.

Finally, in relation to interactions A × G, male prime cats (2–≤7 years old) had higher (P<0.001) d-ROM values than females of the same age (194.2 ± 13.3 CarrU and 118.3 ± 15.9 CarrU, respectively). No differences were found between mature animals, independently of sex (131.1 ± 15.9 CarrU and 133.0 ± 15.9 CarrU for males and females, respectively). Antioxidant defence was not different among groups, although we observed a decrease with age in males (395.3 ± 25.5 µmol HClO/ml for prime males and 359.7 ± 40.4 µmol HClO/ml for mature male cats). Finally, OSi values were higher in males than females, with statistical differences (P = 0.037) in those included in the A-1 group (0.34 ± 0.5 in females; 0.52 ± 0.5 in males), suggesting that at the age of of 2–7 years young males are subjected to more internal OS.

Two facts may be pointed out from this study: (i) this is the first report of redox state values in clinically normal cats in order to define protective nutritional strategies based on antioxidant supplementation, and (ii) this study shows that male cats are a population under risk of OS, this risk being more relevant in the prime period. This fact could probably be of influence in the lack of a healthy male population in the senior age group.

A correct biochemical evaluation of oxidative balance is a good premise to prevent and eventually to treat the effects of OS not only in human, but also in veterinary, medicine, where interest toward free radicals and antioxidants is increasing. 8 In addition, we consider that it is important to evaluate not only concentrations of oxidants and antioxidants separately, but also to analyse their relationship through a proportion or ratio because, in fact, it is the imbalance between oxidants and the antioxidants that defines the concept of OS. 9

Results of the d-ROM test in our sampled cats were between 72.0 and 282 CarrU. This interval was higher than those obtained by Pasquini et al 10 in healthy dogs (56.4–91.4 CarrU), indicating that OS studies of canine medicine cannot always be applied to feline medicine. This discrepancy may be explained by differences in the oxidant/antioxidant plasma components between both species.

Regarding the antioxidant defence, assessment of OXY shows a range from 269.5 to 664.9 µmol HClO/ml. One of the first approaches on this parameter was made in bovine medicine by Abuelo et al, 3 who showed an interval between 273.8 and 880.9 µmol HClO/ml. Finally, mean OSi ratio was established to be between 0.36 and 0.44 for healthy cats, while healthy cows show a lower ratio (0.30). 3 Thus, it is clear that metabolic peculiarities for each species determine different redox balance.

Studies of healthy dogs revealed higher plasma oxidant concentrations in male dogs than in female ones. 11 The same fact was found to be true in our study, but sex differences were more pronounced. Prime cats, especially males, are subjected to more harmful effects of free radicals and lipid peroxidation as products of cell metabolism. Studies performed on mitochondria of different species of mammal revealed that lower susceptibility to lipid peroxidation is a precondition for a longer lifespan. This may explain why in senior groups only healthy females were found. In addition, these findings are in disagreement with those that reported an increase in free radical generation with ageing, 1 although most of these reports of human beings or animals with shorter lifespans (eg, rats).

In addition to age, there is good evidence to show that sex differences in oxidative status exist in different species. According to studies in human medicine 12 DNA and lipid oxidation increases with age and is more pronounced in men than in women. In many species, females live longer than males and it is possible that this is associated with free radicals, which are found in lower amounts in the mitochondria of females. 1

In relation to the antioxidant defence, despite the numerically higher OXY values in primes and males, the lack of differences between groups indicates that this protective barrier is not in accordance with the oxidant aggression. Referring back to human studies, 12 some antioxidants decrease with age and are more pronounced in men than in women (similar evolution is observed in the studied cats). Therefore, the organism is more vulnerable to free radical species and prone to cellular and subcellular damage, 13 leading to chronic diseases, such as diabetes or heart problems — serious diseases that can strike the elderly male cat. The OSi value confirms this redox imbalance.

Previous studies have shown that increased dietary levels of antioxidants in dogs and cats may decrease in vivo measures of oxidative damage, 14 but failed to establish the most appropriate time. Taking into account A × G interactions, and the meaning of OSi (the higher the amount, the worse the result), we focused, obviously, on prime male cats. This period probably determines lifespan and quality of life in later periods. This is an interesting observation because depending on gender, nutritional protocols or even nutritional tricks should be applied to this group to give extra antioxidant support. In a clinical setting it is recognised that owners of older pets are often reluctant to alter their pet’s diet and that the presence of systemic disease may also limit the use of diets specifically designed for the control of OS. 15 The proposal of a nutritional supplement at an early time is therefore of clinical interest for later life stages.

Conclusions

Although we cannot obviate that values given for the cats of our study may be subject to variations attributable to stress, the environment in which they live and even the type of commercial diet they are fed, our results suggest that male cats are a population at risk when compared with females, especially between 2 and 7 years of age. Nutritional strategies among this population looking for additional antioxidant support would probably avoid an OS status that predisposes to chronic processes in senior male cats. Further clinical trials investigating factors that influence OS in cats are strongly recommended.

Footnotes

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

The authors do not have any potential conflicts of interest to declare.

Accepted: 23 October 2012

References

- 1. Sastre J, Borras C, Garcia-Sala D, Lloret A, Pallardo FV, Vina J. Mitochondrial damage in aging and apoptosis. Ann New York Acad. Sci 2002; 959: 448–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sharma RK, Pasqualotto FF, Nelson DR, Thomas AJ, Agarwal A. The reactive oxygen species vs total antioxidant capacity score is a new measure of oxidative stress to predict male infertility. Human Reprod 1999; 14: 2801–2807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Abuelo A, Hernández J, Pereira V, Benedito JL, Castillo C. Oxidative stress index. A new tool to evaluate oxidative status during transition period in dairy cows. In: Proceedings of the 6th European Congress of Bovine Health Management 7-9 September 2011, Belgium, pp 51. Ed. Societé Belge Francophone de Buiatrie. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Feline Advisory Bureau (FAB). WellCat for life veterinary handbook. Available at www.fabcats.org/wellcat/publications/index.php (accessed 24 April 2012).

- 5. World Small Animal Veterinary Association (WSAVA) Nutritional Assesment Guidelines. J Small Anim Pract 2011; 52: 385–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Alberti A, Bolognini L, Macciantelli D, Carratelli M. The radical cation of N, N-diethylpara-phenylendiamine: a possibile indicatopr of oxidative stress in biological samples. Res Chem Intermediates 2000; 26: 253–267. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Trotti R, Carratelli M, Barbieri M, Micieli G, Bosone D, Rondanelli M, Bo P. Oxidative stress and a thrombophilic condition in alcoholics without severe liver disease. Haematologica 2001; 86: 85–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Castillo C, Wittwer F, Cerón JJ. Oxidative stress in veterinary medicine. Vet Med Int 2011; Special issue: 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Castillo C, Hernández J, Bravo A, López-Alonso M, Pereira V, Benedito JL. Oxidative status during late pregnancy and early lactation in dairy cows. Vet J 2005; 169: 286–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pasquini A, Luchetti E, Marchetti V, Cardini G. Analytical performances of d-ROMs test and BAP test in canine plasma. Definition of the normal range in healthy Labrador dogs. Vet Res Comm 2008; 32: 137–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Todorova I, Simeonova G, Dinev D, Gadjeva V. Reference values of oxidative stress parameters (MDA, SOD, CAT) in dogs and cats. Comp Clin Path 2005; 13: 190–194. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fano G, Mecocci P, Vecchiet J, Belia S, Fulle S, Polidori MC, et al. Age and sex influence on oxidative damage and functional status in human skeletal muscle. J Muscle Res Cell Motility 2001; 22: 345–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chan DL. The role of nutrients in modulating disease. J Small Anim Pract 2008; 49: 266–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jewell DE, Toll PW, Wedekind KJ, Zicker SC. Effect of increasing dietary antioxidants on concentrations of vitamin E and total alkenals in serum of dogs and cats. Vet Therapeut 2000; 1: 264–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Heath SE, Barabas S, Craze PG. Nutritional supplementation in cases of canine cognitive dysfunction. A clinical trial. Appl Anim Behav Sci 2007; 105: 284–296. [Google Scholar]