Abstract

A 1-year-old, female, previously spayed domestic shorthair cat presented with abnormal behavior characterized by rubbing up against objects, vocalization and abnormal body posture. A diagnostic laparoscopy was performed and a dilated segment of the left uterus and ovary was found in association with ipsilateral renal agenesis. Papillary hyperplasia of the endometrium of the dilated segment was found on histopathology. The occurrence and findings of this condition are reviewed.

Case Report

An approximately 6-month-old, female domestic shorthair cat was presented for clinical examination after adoption from the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (SPCA). The patient was previously spayed and up to date with vaccines. Additionally, tests for feline leukemia virus and feline immunodeficiency virus were negative. Six months after the first clinical examination, the patient was brought back with complaints of increased vocalization and ‘rubbing up against objects’. The owner reported that during ovariohisterectomy (OHE) only one ovary and half of the uterus had been found. Because the OHE procedure was performed at a spay clinic for the SPCA, documentation of the surgical findings was not available. Upon examination, the patient was febrile with clinical signs of an upper respiratory tract infection, and it was treated accordingly. After a couple of days the owner reported continued abnormal behavior, characterized by rubbing up against objects, vocalizing loudly and exhibiting a crouching body posture. Exploratory surgery was performed to determine if there was any remnant of ovarian tissue to explain the behavior. The pre-surgical physical examination was normal. The surgical procedure revealed a ‘finger like’ segment (2 cm long) of left uterine horn, followed cranially by a thin, string-like tissue connecting it to a rounded, dilated and well-vascularized segment of uterus that measured approximately 4 cm in diameter. The left ovary was present (Figure 1). The right uterine horn and ovary were not present. Additionally, the left kidney was not found. The segment of uterus and ovary were removed using a routine OHE procedure. Tissues were submitted for histopathologic examination.

Figure 1.

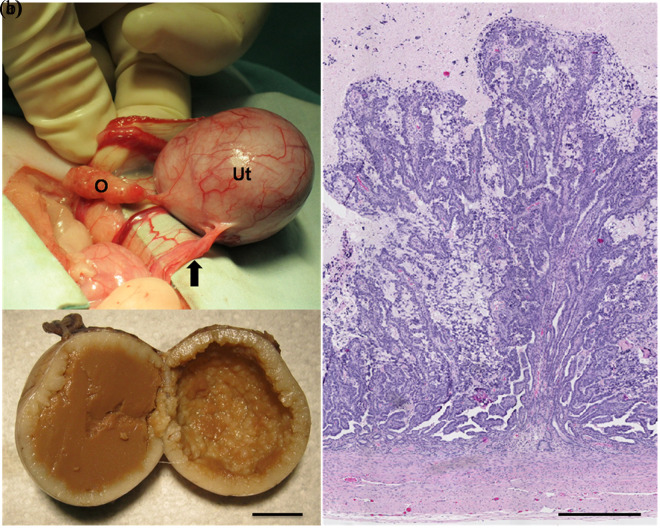

(a) Intraoperative photograph of the left ovary and uterus. The dilated portion of the uterus is connected caudally to a string-like tissue (arrow). The ovary has a normal appearance. O = ovary; Ut = uterus. (b) Formalin-fixed uterus. The lumen is filled with a brown dense amorphous material and the endometrial surface is markedly uneven. Bar = 1 cm. (c) Histological findings in the dilated portion of the uterus. Numerous papillae of the endometrium project into the lumen, which contains cellular debris and a globular proteinaceous material. Bar = 500 µm

Grossly, a rounded, firm section of uterus was evaluated, which measured 3.5 × 3.0 × 3.0 cm. The blood vessels in the serosa were prominent. An ovary was attached to one pole and a thin, string-like tissue to the other. On cut section, the uterus was filled with a brown, dense amorphous material. The internal (endometrial) surface of the uterus was markedly uneven (Figure 1). The uterus, the ovary and the string-like tissue were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, routinely processed and embedded in paraffin. Sections (5 μm) were stained with hematoxylin and eosin for histopathologic evaluation.

The histopathologic evaluation of the uterus revealed the lumen to be filled with degenerated and necrotic desquamated cells immersed in a globular eosinophilic proteinaceous material. Numerous prominent papillae of the endometrium projected into the lumen. These papillae were composed of endometrial cells supported in a very fine fibrovascular stroma (Figure 1). Epithelial cells had moderate amounts of amphophilic cytoplasm, round-to-oval nuclei with minimal anisokaryosis, one prominent nucleolus and coarsely stippled chromatin. There were four to eight mitotic figures per high power (40×) magnification field. A few endometrial glands, some of them dilated, were present deep within the endometrial stroma. The myometrium was unremarkable. A longitudinal section of the ovary contained seven prominent corpora lutea. The string-like tissue attached to the caudal aspect of the uterus was composed of numerous tortuous blood vessels, embedded in a sheath of dense fibrous tissue and smooth muscle (not shown).

Based on the clinical history and the gross and histological findings, the animal was diagnosed with estrus due to the presence of the left ovary, segmental aplasia of the posterior left uterine horn with papillary hyperplasia of the cranial segment and ipsilateral renal agenesis.

In domestic animals the majority of uterine congenital anomalies involve the uterine horns. Segmental uterine aplasia is characterized by an absence of portions of the uterine horn, resulting in the isolation of cranial segments from more distal segments. 1 It results from segmental defects in paramesonephric (or Müllerian) duct development. Embryologically, the paramesonephric duct first differentiates in feline fetuses measuring 1.2 cm crown-rump length (CRL). At 3.2 cm CRL, the ducts of both sexes are well developed and reach the urogenital sinus. At this time, male–female differentiation takes place. 2 As soon as the distal tips of the paramesonephric ducts adhere to each other, and before they contact the sinusal tubercle, they begin to fuse forming a tube with a single lumen called the genital canal. The genital canal gives rise to the anterior portion of the vagina and the uterus. 3 It is at this stage that segmental aplasia may take place, and it may be unilateral or bilateral.

Uterine aplasia interrupts the normal expulsion of endometrial secretions. The isolated uterine segments frequently become cystic and hyperplastic, with sloughed epithelial cells forming an inspissated putty-like calculus that distends the obstructed segment.1,4,5 Interestingly, the gross and histological appearance of the dilated portion of the uterus in this case was reminiscent of findings described for pseudopregnancy. Similarities included prominent segmental proliferative and secretory changes in the endometrium, with long papillary projections protruding into multiloculated cysts and the presence of mucometra or hydrometra. 1 Nevertheless, endometrial hyperplasia is not a constant feature in segmental uterine aplasia. Marked atrophy of the endometrium has also been observed with this condition, even in the presence of normally-functioning ovaries. 6

From a clinical diagnostic perspective, ultrasound might have been used to identify remnants of ovarian or uterine tissue, but findings using this technology are dependent on the size of the tissue remnant, stage of the estrus cycle and expertise of the ultrasonographer. In this case, the uterine remnant might have been identified, and the differential diagnoses would have included early pregnancy, pyometra, hematometra, mucometra and hydrometra. 7 Additionally, as this animal was in estrus, the presence of corpora lutea would have helped identifying ovarian remnants. 8 In humans, Müllerian duct anomalies are difficult to detect by ultrasonography because of the low prevalence of these abnormalities and the wide variation of presentation, with a reported sensitivity as low as 42% with ultrasonography.9,10 Ultrasonographic studies were not performed in this animal because of financial restrictions, and exploratory surgery was considered a better option as both a diagnostic and treatment procedure.

The coexistence of uterine aplasia with ipsilateral renal agenesis is uncommon in cats, with isolated reports in the veterinary literature.6,11,12 Nevertheless, there is a common embryonic mesoderm origin for the urinary and genital systems and the coexistence of renal and uterine abnormalities is very well recognized in humans. 13 Two paired Müllerian tubes ultimately develop into the Fallopian tubes, uterus, cervix and the anterior section of the vagina. Unilateral defects of the paramesoneophric duct and metanephros may result in ipsilateral defects in both urinary and genital systems because of the close developmental association of these two systems. 14 Interestingly, in humans, a condition referred to as Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser syndrome (MRKH), is characterized by congenital aplasia of the uterus and the upper part of the vagina. This syndrome may occur in isolation (type I), but is more frequently associated with renal, skeletal, and, to a lesser extent, auditory and cardiac defects (MRKH type II or Müllerian Renal Cervical Somite association). 15 This syndrome has not been described in animals.

In humans with Müllerian duct anomalies or MRKH syndrome there is a range of coexisting renal anomalies, including renal agenesis, dysplasia or ectopia.13,15,16 In this regard, McIntyre et al 12 found that ipsilateral renal agenesis was present in almost 30% of cats with uterine anomalies in which the kidneys were evaluated, and advised that once a uterine developmental anomaly is identified, evaluation of both kidneys and ovaries should be performed.

Conclusions

Although the association between urinary and genital malformations has long been recognized, the etiology of this syndrome remains unclear. In humans, Müllerian duct abnormalities are sporadic and attributed to polygenic and multifactorial causes. 17 The use of metothrexate or diethylstilbestrol, viral infections, ionizing radiation and pregnancy hypoxia may contribute to the occurrence of Müllerian malformations.18,19 In MRKH syndrome, the etiology is unknown, but increasing numbers of familial cases now support the hypothesis of a genetic cause. 15 In veterinary medicine, similar associations have not been identified.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr Michael Mirsky for the review of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Accepted: 19 October 2012

References

- 1. Jones TC, Hunt RD, King NW. The genital system. In: Jones TC, Hunt RD, King NW. (eds). Veterinary pathology. 6th ed. Baltimore, MD: Lipincott Williams & Wilkins, 1997, pp 1149–1222. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Inomata T, Ninomiya H, Sakita K, et al. Developmental changes of Müllerian and Wolffian ducts in domestic cat fetuses. Exp Anim 2009; 58: 41–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Larsen WJ. Development of the urogenital system. In: Larsen WJ. (ed). Human embryology, 2nd ed. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1997, pp 261–310. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Morris LHA, Fairles J, Chenier T, Johnson WH. Segmental aplasia of the left paramesonephric duct in the cow. Can Vet J 1999; 40: 884–885. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schlafer DH, Miller RB. Female genital system. In: Maxie MG. (ed). Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer’s pathology of domestic animals, Vol. 3. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier, 2007, pp 429–564. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Goo MJ, Williams BH, Hong IH, et al. Multiple urogenital abnormalities in a Persian cat. J Feline Med Surg 2009; 11: 153–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dennis R, Kirberger R, Barr F, Wrigley R. The urogenital tract. In: Dennis R, Kirberger R, Barr F, Wrigley R. (eds). Handbook of small animal radiology and ultrasound. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier, 2010, pp 297–330. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mattoon JS, Nyland TG. Ovaries and uterus. In: Nyland TG, Mattoon JS. (eds). Small animal diagnostic ultrasound. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier, 2002, pp 231–249. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mazouni C, Girard G, Deter R, et al. Diagnosis of Müllerian anomalies in adults: evaluation of practice. Fertile Steril 2008; 89: 219–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Soares SR, Barbosa dos Reis MM, Camargos AF. Diagnosis accuracy of sonohysterography, transvaginal sonography and hysterosalpingography in patients with uterine cavity diseases. Fertil Steril 2000; 73: 406–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chang J, Jung J, Yoon J, et al. Segmental aplasia of the uterine horn with ipsilateral renal agenesis in a cat. J Vet Med Sci 2008; 70: 641–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. McIntyre RL, Levy JK, Roberts JF, Reep RL. Developmental uterine anomalies in cats and dogs undergoing elective ovariohysterectomy. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2010; 237: 542–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Acien P, Acien M, Sanchez-Ferrer M. Complex malformations of the female genital tract. New types and revision of classification. Hum Reprod 2004; 19: 2377–2384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sameshima H, Nagai K, Ikenoue T. Single vaginal ectopic ureter of fetal metanephric duct origin, ipsilateral kidney agenesis, and ipsilateral rudimentary uterine horn of the bicornuate uterus. Gynecol Oncol 2005; 97: 276–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Morcel K, Camborieux L. Programme de Recherche sur les Aplasies Müllériennes and Guerrier D. Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser (MRKH) syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2007; 2:13–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pittock ST, Babovic-Vuksanovic D, Lteif A. Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser anomaly and its associated malformations. Am J Med Genet A 2005; 135: 314–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rackow BW, Arici A. Reproductive performance of women with Müllerian abnormalities. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2007; 19: 229–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sharara FI. Complete uterine septum with cervical duplication, longitudinal vaginal septum and duplication of a renal collecting system. A case report. J Reprod Med 1998; 43: 1055–1059. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Homer HA, Li TC, Cooke ID. The septate uterus: a review of management and reproductive outcome. Fertil Steril 2000; 73: 1–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]