Abstract

An internet-based survey was conducted to determine common strategies for control of feline upper respiratory infections (URI) in animal shelters. Two hundred and fifty-eight North American shelters responded, representing a spectrum of 57% private non-profit, 27% municipal and 16% combined private non-profit-municipal shelters. All but nine shelters reported having a regular relationship with a veterinarian, 53% had full-time veterinarians and 62% indicated full-time (non-veterinarian) medical staff. However, in 35% of facilities, non-medical shelter management staff determined what medication an individual cat could receive, with 5% of facilities making that decision without indicating the involvement of a veterinarian or technician. Ninety-one percent of shelters had an isolation area for clinically ill cats. The most commonly used antimicrobial was doxycycline (52%), followed by amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (33%). Shelters are using a wide range of prevention measures and therapeutics, leaving room for studying URI in different settings to improve understanding of optimal protocols.

Short Communication

Homeless cats cared for by animal shelter facilities are at high risk for feline infectious upper respiratory infections (URI). Because this disease is common, URI is a significant feline health and welfare issue in shelters.1,2 In some shelters, URI may ultimately result in euthanasia rather than a live release outcome. 3 Many shelters invest significant resources in efforts to treat affected cats. While such therapy is often lifesaving, well intended, but poorly designed, URI treatment programs can also result in prolonged shelter stays, poor welfare, increased severity of disease and a decrease in live release rates. Research that targets preventive measures to maintain wellness, as well as effective, efficient and economical therapeutic interventions when URI occurs, is therefore urgently needed.

While previous studies have investigated common organisms that play a role in shelter URI1,3–7 published information regarding the range of actual shelter URI management and treatment practices and protocols is limited. One great difficulty is that shelter practices vary considerably. Even within a single facility, protocols and practices often do not stay the same for long. Only in the year prior to performance of this survey have guidelines for standards of care for shelters been published in the USA. 8 Because shelters are largely unregulated in North America, many standards for disease control, including isolation of ill animals, judicious selection of antimicrobials, minimum data collection, and even basic sanitation are variably practiced and rarely evaluated for effect.

The goal of the study was to document protocols and policies used for management and treatment of feline URI across a spectrum of shelter types to gain a better understanding of current practices.

Survey participants were invited through a cover letter that explained the project as well as confidentiality of results. The project was approved by the Internal Review Board of the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA). Distribution occurred through shelter-focused listservs, including ASPCApro, the Society of Animal Welfare Administrators, the Association of Shelter Veterinarians and the Humane Society of the United States. All shelters identified as municipal shelters in the ASPCA Contact Database were contacted by email. Foster networks and programs that did not handle cats were excluded during analysis. Two hundred and fifty-eight shelters responded to the survey.

The survey was open on SurveyMonkey between 18 December 2010 and 28 March 2011. The survey was developed by us with input from other experienced shelter veterinarians. All questions were multiple choice unless otherwise specified. Information about the individual participants’ backgrounds was not collected. Data were collected on shelter type, as well as 2009 and 2010 cat intake (number of cats and kittens the shelter admitted on an annual basis), live release (adoption, rescue, reclaim, transfer) and estimated average length of stay (defined as # cages/total intake annually of cats multiplied by 365). Optional questions included the shelter’s location and an open-ended question for comments about feline URI.

Medical staffing questions delineated the specific medical staff and any regular relationship the shelter had with a veterinarian. Positions were identified as full, part-time, private practice or volunteer; responders could check all that applied. Questions determined if the facility based treatment and disease management on written protocols, and, if so, who was primarily responsible for developing those protocols and the medications administered.

Questions regarding practices that affect health included whether each cat was observed daily for health, which personnel did this, vaccination practices, primary housing type, action taken when a cat was determined to have URI and isolation options. Respondents were asked when cats were placed on antimicrobials, first and second choice antimicrobials, other supportive care provided, factors leading to a change in antimicrobial therapy, frequency of rechecks of affected cats and by which staff member, and at what point affected cats were considered ready for adoption.

Categorical data were summarized using counts and percentages. Intake and live release data and average estimated length of stay were summarized using medians and minimum/maximum. Live release rate was provided directly by some shelters; otherwise it was calculated when possible by dividing the year’s live releases by the year’s intake. Open-ended questions and questions with ‘other’ answers were reviewed and recoded into listed categories or summarized by the authors.

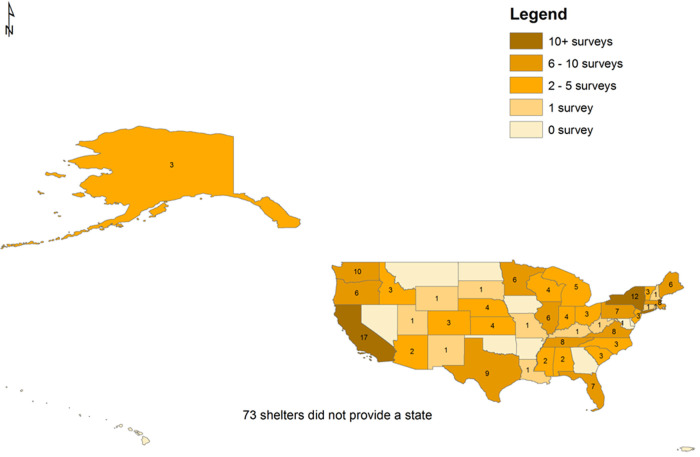

Two hundred and fifty-eight North American animal shelters responded to the survey. Eleven shelters (11/258 or 4% were from Canada). In the USA, 42 states were represented, with California, New York, Washington and Texas having the most responses (Figure 1). There were 148/258 (57%) private non-profit, 69/258 (27%) municipal and 41/258 (16%) combined private non-profit-municipal shelters.

Figure 1.

The distribution by state of the shelters responding to a survey on feline upper respiratory infection management in the USA

Not all shelters responded to all questions. Of the 119/258 shelters responding, annual feline intake varied from 2 to 28,230 in 2009 (median of 1444). For 2010, 112 respondents reported an annual intake range from 0 to 17,069 (median of 1287). The largest intake agencies for 2009 did not have total 2010 intake data available. Live release rates were reported for 109 agencies in 2009 (4% to 100%, median of 73%) and for 101 agencies in 2010 (4% to 100%, median of 75%). Estimated average length of stay varied from 5 days to >120 days, with a median of 22 days from 129 respondents. Average length of stay was likely an underestimated value in this study as many shelters may not know to calculate multiple animals per cage or group room or accurately know their shelter cage capacity.

Over half of responding shelters 118/199 (59%) described the majority of cat housing as individual stainless steel cages compared with 25/199 (13%) group room housing and 26/199 (13%) individual condominium housing. Other types of housing (fiberglass, wire or some combination) were selected by 30/199 (15%) of shelters. Of 199 shelters who responded, 181 (91%) answered yes when asked if there was a quarantine/isolation area to separate sick cats from the general population. Although the proper definition of a quarantine area does not entail housing of sick animals, the term was used as many shelters still use the terms quarantine and isolation interchangeably.

All but nine of 258 shelters had a regular relationship with a veterinarian and all had some medical staff (technician, assistant, etc) (Table 1). Just over half of respondents indicated a full-time veterinarian. Cross tabulation with other responses indicated that 22% of those were private practice veterinarians used for shelter services and 15% were volunteers. We assume that these shelters had several non-staff veterinarians who provided at least one full-time equivalent. Use of part-time veterinary services occurred in 74 (29%) facilities with 50% in private practices and 32% volunteer (no information on remaining veterinary sources). The sum is greater than 100% owing to more than one response being an option. Overall, 117 (45%) shelters used a private practice veterinarian and 45 (17%) used volunteers. Table 1 describes for the 252 shelters responding the primary personnel who establish treatment protocols and who observed cats for health.

Table 1.

Key question responses from shelters responding to a survey on feline upper respiratory infections (URI) in North America

| Variable | Number of facilities | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Does the facility have a regular relationship with a veterinarian? n = 258 | ||

| Yes | 249 | 97 |

| No | 9 | 3 |

| If yes, check all those that apply: | ||

| Full-time staff | 138 | 53 |

| Part-time staff | 74 | 29 |

| Use of private practice veterinarian | 117 | 45 |

| Volunteer | 45 | 17 |

| Does the facility have medical staff (technician, assistant, etc)? n = 250 | ||

| Yes | 186 | 74 |

| No | 64 | 26 |

| If yes: n = 186 | ||

| Only full-time | 116 | 62 |

| Only part-time | 8 | 4 |

| Only volunteer | 3 | 2 |

| Full-, part-time, and volunteer | 20 | 11 |

| Full- and part-time | 34 | 18 |

| Full-time and volunteer | 3 | 2 |

| Part-time and volunteer | 2 | 1 |

| Of the following choices, who is primarily responsible for establishing and evaluating general treatment protocols? n = 252 | ||

| Veterinary | 148 | 59 |

| Manager | 72 | 29 |

| Technician | 21 | 8 |

| Other personnel (volunteer, team of staff members, animal control officer) | 11 | 4 |

| Are all cats in the shelter individually observed to determine health status on a daily basis? n = 245 | ||

| Yes | 226 | 92 |

| No | 19 | 7 |

| If yes, who is primarily performing this duty? n = 223 | ||

| Trained staff | 111 | 50 |

| Technicians | 55 | 25 |

| Managers | 23 | 10 |

| Veterinarians | 16 | 7 |

| Volunteers or others | 18 | 8 |

| Is there a current written protocol for URI management at the facility? n = 247 | ||

| Yes | 138 | 56 |

| No | 109 | 44 |

| When cats with typical URI signs (sneezing, nasal discharge, ocular discharge) were identified you: n = 199 | ||

| Move to another area in shelter for treatment | 148 | 57 |

| Keep in current location and treat | 33 | 17 |

| Depends on severity, adoptability | 12 | 5 |

| Euthanase | 6 | 3 |

| Of the following choices, who can decide what medication an individual cat with URI receives? (check any that apply) n = 258 | ||

| Veterinarian | 224 | 87 |

| Technician | 100 | 39 |

| Manager | 79 | 31 |

| Manager without veterinary technician or veterinarian indicated | 11 | 4 |

| Other | 16 | 6 |

| Other without veterinary technician or veterinarian indicated | 2 | 1 |

| Are regular recheck exams performed on cats being treated for URI? n = 197 | ||

| Yes | 178 | 69 |

| No | 19 | 7 |

| If yes, by whom? (check all that apply) n = 178 | ||

| Veterinarian | 124 | 70 |

| Technician | 94 | 53 |

| Trained staff | 84 | 47 |

| Manager | 42 | 24 |

| Volunteers | 14 | 8 |

| Others | 2 | 1 |

Of the 203 shelters who responded, only four (2%) did not vaccinate. Of the 199 that vaccinated, 171 (86%) vaccinated all/most cats whereas 28 (14%) vaccinated ‘some’ cats. In the 196 shelters that responded about the vaccine routinely provided, the most common were feline rhinotracheitis, calicivirus, panleukopenia in 193 (98%), Chlamydophila felis in 54 (28%) and Bordetella bronchiseptica in 18 (9%). Vaccination of cats was performed immediately in 88/195 (45%) or within hours for 68/195 (35%) of shelters, or within days of arrival in 38/195 (19%). Vaccine types included modified live (162/199; 81%), killed (60/199; 30%) and intranasal (53/199; 27%).

Of those shelters without written protocols (Table 1), 78/109 (72%) indicated that a known standard URI treatment policy existed despite it being unwritten. The clinical signs upon which antimicrobial treatment was initiated included any sneezing or other URI signs (118/258; 46%) or just upon development of colored nasal discharge (139/258; 54%). The decision about which antimicrobial an individual cat with URI receives was made by a veterinarian in 87% of shelters, a technician in 39% of shelters, by a manager in 31%, by a manager without indication of veterinarian or technician in 4% of facilities, by another staff member in 6%, and by other staff without indication of veterinarian or technician in 1% (Table 1). The most common first choice antimicrobial was doxycycline (n = 103) followed by amoxicillin or Clavamox (n = 65) then azithromycin (n = 13). The most common second choice antimicrobial was amoxicillin or Clavamox (n = 57) followed by doxycycline (n = 45) or azithromycin (n = 44). The decision to change to a second choice antimicrobial was based upon lack of improvement during therapy 84/175 (48%) or lack of resolution on completion of therapy 81/175 (46%). Dose and duration of therapy was not requested. The most common supportive treatments, in order of use, were cleaning eyes and nose, fluid administration, nutrition/appetite stimulation, lysine and nebulization.

For the frequency of follow-up examinations/rechecks performed, a range of time (eg, 14–21 days) was often provided. Of the 152 responders, rechecks occurred once daily or more often in 73 (48%) facilities. Staff members performing URI rechecks are listed in Table 1. Adoption was allowed for URI cats only upon completion of antimicrobial therapy and in the absence of clinical signs in 109/193 shelters (56%), after resolution of clinical signs in 49/193 (25%) or during treatment in 35/193 (18%).

Few studies have investigated feline upper respiratory management and treatment practices and protocols in shelter facilities in North America. The Association of Shelter Veterinarians considers as a standard of care that all healthcare practices be developed in consultation with a veterinarian because the availability of veterinary-guided protocols are the foundation for day-to-day shelter management. 8 Of interest in this survey, a very high proportion of responding facilities (96%) reported a ‘regular relationship’ with a veterinarian, and over half reported a full-time veterinarian on staff, yet only in 59% was a veterinarian responsible for primarily establishing and evaluating general protocols for veterinary treatments and disease management. The reason for this low percentage is not clear and was not determined by this study, but, potentially, this demonstrates a variable level of veterinary involvement in management of at least one important infectious disease in animal shelters. One possible reason for veterinarians not being responsible for protocols in all shelters that have a veterinarian is that in most state veterinary practice acts, animal shelters are not even mentioned, and in many states or provinces shelters are considered the owners of the animals in their care. In such circumstances, shelters may believe it is within their discretion to make treatment decisions without veterinary oversight. However, a valid veterinary client–patient relationship is still required for prescription drugs, possibly accounting for the reported high percentage of relationships, which could be just for prescribing medication. Veterinarians play an essential role when the decision is reached to use antimicrobials for therapy both in selection of antimicrobials and their judicious use. This finding has important implications, not only for the health and welfare of cats in shelters, but potentially for public health as well, and could represent an opportunity for the veterinary profession to become more involved in raising the standard of care in shelter medicine.

Conclusions

Although this study included a broad range of shelters, it nonetheless does not represent a random sample and thus cannot be considered representative of sheltering in North America. It also is likely that based on the distribution of the survey through shelter focused listservs, the responding shelters are more proactive in seeking information related to shelter animal wellness, which would bias our respondents to more progressive shelters with computer access. ASPCApro and the Humane Society of the United States both reach shelter professionals, the Society of Animal Welfare Administrators targets shelter leadership and the Association of Shelter Veterinarians majority membership is veterinarians working with shelters. This study’s goal was to learn about the range of therapeutic and control strategies in common use in shelters in North America. Shelters are complex environments that make study and comparison of practices and protocols across a range of programs challenging. This survey is one of only a few such wide scale studies conducted, so the information obtained will be useful in future targeting of strategies to save the lives of cats at risk in North American shelters because of URI.

Acknowledgments

We thank Rachana Bhattarai for creating the figure.

Footnotes

Funding: The authors received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors for the preparation of this short communication.

The authors do not have any potential conflicts of interest to declare.

Accepted: 30 July 2012

References

- 1. Bannasch MJ, Foley JE. Epidemiologic evaluation of multiple respiratory pathogens in cats in animal shelters. J Feline Med Surg 2005; 7: 109–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dinnage J, Scarlett JM, Richards JR. Descriptive epidemiology of feline upper respiratory tract disease in an animal shelter. J Feline Med Surg 2009; 11: 816–825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Scarlett JM, Fonhofer L. Feline upper respiratory infection control in northeastern shelters. Senior seminar paper, Cornell College of Veterinary Medicine, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cape L. Feline idiopathic chronic rhinosinusitis: a retrospective study of 30 cases. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 1992; 23: 149–155. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Johnson LR, Foley JE, De Cock HE, Clarke HE, Maggs DJ. Assessment of infectious organisms associated with chronic rhinosinusitis in cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2005; 227: 579–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pedersen NC, Sato R, Foley JE, et al. Common virus infections in cats, before and after being placed in shelters, with emphasis on feline enteric coronavirus. J Feline Med Surg 2004; 6: 83–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Veir JK, Ruch-Gallie R, Spindel ME, Lappin MR. Prevalence of selected infectious organisms and comparison of two anatomic sampling sites in shelter cats with upper respiratory tract disease. J Feline Med Surg 2008; 10: 542–550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Newbury S, Blinn M, Bushby PA, et al. Association of Shelter Veterinarians guidelines for standards of care in animal shelters, http://www.sheltervet.org/associations/4853/files/Shelter%20Standards%20Dec2010.pdf (2010, accessed 8 August 2011).