Abstract

This paper presents an application of the Lifespan Model of Ethnic-Racial Identity (ERI) Development (see Williams, et al., in press). Using a tripartite approach, we present the affective, behavioral, and cognitive aspects of ERI in a framework that can be adapted for group and individual psychosocial interventions across the lifespan. These A-B-C anchors are presented in developmental contexts as well as the larger social contexts of systemic oppression and current and historical sociopolitical climates. It is ultimately the aspiration of this identity work that individuals will engage in ERI meaning-making, drawing from the implicit and explicit aspects of their A-B-Cs, to support a healthy and positive sense of themselves and others as members of ethnic-racial social groups.

Ethnic-racial identity (ERI) has many implications for the development and well-being of children, adolescents, and adults of color. Broadly, individuals who form a strong and positive sense of their ERI often experience better academic outcomes, psychological adjustment (e.g., self-esteem), health, and overall well-being (Rivas-Drake, Seaton et al., 2014). The benefits of a well-developed ERI are many, including reduced risk behaviors in adolescence, fewer chronic illnesses in adulthood, and greater emotion regulation in childhood (see review by Marks et al., 2015). Strong, positive ERI also has been linked to healthy adaptations, such as building resiliency in the face of discrimination (Marks et al., 2015; Motti-Stefanidi & Masten, 2017). Although ERI experiences are not always centrally important or experienced as positive to an individual at a given time or point in their identity development, research suggests that the process of supporting individuals’ ERI exploration and consolidation are critically important (e.g., identity conversion, or similar processes of integrating one’s racial identity into the larger identity so that it is held; Sheets, 1999). These healthy psychological adaptation patterns are observed across many ethnic-racial groups in the U.S. and in Europe, and have led to recent intervention efforts targeting ERI as a resilience-building tool for minority youth1 (e.g., Umaña-Taylor, Douglass et al., 2018). Importantly, past research has established the many ways that families and schools provide essential supports and intentional scaffolding in raising their children to be racially conscious and support positive youth ERI’s – whether through pride and positive affect or through more cognitive awareness and integration of identities (e.g., Aldana & Byrd, 2015; Harding et al., 2017). Still, limited attention has been given to how ERI development may be promoted in minority populations in the intervention literature, which represents a missed opportunity to highlight and leverage the strengths and well-being of Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) in the U.S.

The purpose of this paper is to describe a framework that may serve as a guide in developing and applying psychosocial tools and interventions to enhance ERI. Our framework is grounded in a newly-developed lifespan model of ERI (see Williams et al., in press). Briefly, this new model argues for a lifespan perspective on ERI development from infancy through adulthood, and emphasizes the myriad contextual factors that prompt ERI-related meaning-making experiences. Considering the complexity of the lifespan model, our goal was to describe its potential applications with individuals across the lifespan. The framework can be used to guide a comprehensive assessment of individual ERI in a particular place and time, and to identify aspects of individuals’ lived ERI experiences that may call for emotional support, greater awareness, or behavioral activation to help move the individual respond adaptively to ethnic-racial identity-salient experiences such as discrimination or migration. We envision the framework as having broad application in educational, counseling, and clinical settings as a guide for psychoeducational efforts, educational curricula, counseling practice, and psychosocial prevention/intervention programs. Below, we provide a description of the framework and its conceptualization, and then move systematically through its main components. We end by discussing ideas for its application to different developmental periods and present the anticipated benefits of using the framework to help individuals’ ERI development and adaptation to identity-relevant experiences.

THE A-B-C FRAMEWORK OF LIFESPAN ERI DEVELOPMENT: AN OVERVIEW

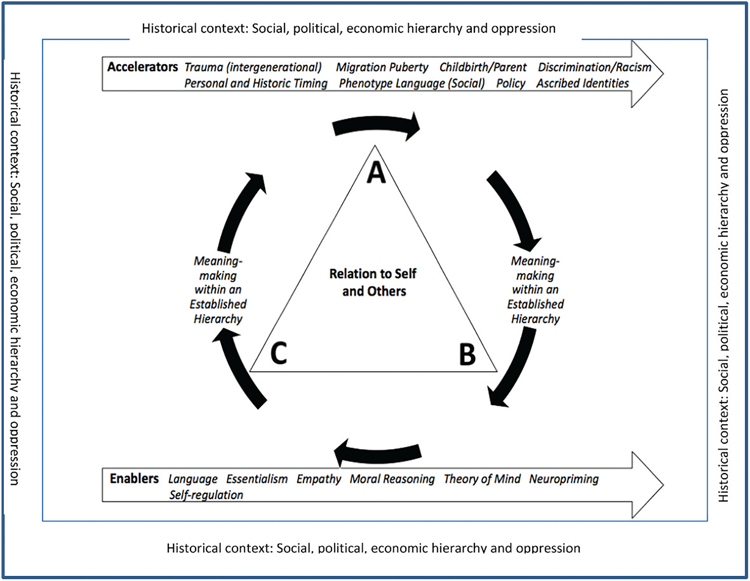

To capture the complexities, nuances, and contextual influences that interact within an individual’s ERI experience at any given moment across the lifespan, we adopted a tripartite affective-behavioral-cognitive (A-B-C) framework situated in larger social and developmental contexts (see Figure 1). In doing so, we reorganized the literature presented in the Lifespan Model (Williams et al., in press) into a framework that can be easily adapted for intervention. At the heart of the triangle rests the central goal of this applied framework: positive ERI development in relation to self and others. We refer here to “positive ERI” not as singular or a predetermined set of attitudes but rather the integration and clarity of ethnicity-race into one’s overall sense of self (Cross, 1991; Sellers, 1998). Here, we emphasize ERI as relational, or as a critical lens through which individuals understand themselves and relate to others. Around the center of the framework stand the tripartite anchors of Affective, Behavioral, and Cognitive. As in traditional A-B-C models (e.g., Ellis, 1955; Zhou et al., 2008), the affective (e.g., attachment, pride), behavioral (e.g., parent’s ERI socialization), and cognitive (e.g., self-labeling, awareness, and identity consolidation) features of ERI are represented as interdependent and multidirectional. We also view all three anchors as equally important. Too often, cognitive aspects of ERI have been emphasized in the early part of the lifespan (see Rogers et al., 2012; Semaj, 1980), without parallel attention to the affective and behavioral components. Likewise, in adulthood, we may attend more to the affective experiences of ERI, without full consideration of how experiences such as discrimination may shift ERI cognition in response (e.g., Branscombe et al., 1999). The comprehensiveness and multidirectionality of this tripartite model are intended to represent the fullness of the ERI developmental experience across all three domains—thinking, feeling, and behaving.

FIGURE 1.

The A-B-C applied framework of ethnic-racial identity development.

Meaning-making activity then surrounds these A-B-Cs in a continual and dynamic process that allows an individual to make sense of, find meaning in, and ultimately integrate their affective, behavioral, and cognitive experiences to form a coherent understanding of their identity (see Erikson, 1968; Motti-Stefanidi & Masten, 2017; Spencer et al., 1995). Importantly, this meaning-making is situated within an established social and political hierarchy (depicted as the outer-most box around the figure). The importance of attending to the contemporary and historical context regarding systems of racism and oppression cannot be underscored strongly enough because individuals will vary greatly in their positionality within these systems, experiencing privilege in some aspects of their ERI development and identity consolidation, and oppression in others. This understanding of multiple positions follows from work on intersectionality, acknowledging the layers of privilege and oppression that individuals can hold in their social identities (Crenshaw, 1989; Velez & Spencer, 2018). For example, a Latinx, phenotypically White, language-minority young person living in a particular U.S. community will see themselves and others in different ways than a Latinx, phenotypically Black, language-majority young person living in another community. The systemic, historical and present-day racism of the U.S. will present both individuals with differing forms of oppression, barriers to health care, educational opportunities, and economic advancement, and discrimination, which will in turn shape their ERI development in unique implicit and explicit ways. That is, each individual’s positionality within established social and political hierarchies will determine how they make meaning of their specific affective, behavioral, and cognitive ERI experiences to ultimately develop an ERI in relation to themselves and others.

According to the framework, this process of meaning-making and ERI development is driven, over developmental and sociohistorical time, by developmental contexts and capacities that serve as accelerators and enablers. We conceptualize enablers as individual developmental capacities that define the ways in which the individual is able to experience and understand the affective, behavioral, and cognitive aspects of their ERI. We highlight neuropriming, language development, self-regulation, theory of mind, empathy, essentialism, and moral reasoning as examples of enablers that produce qualitative shifts in how an individual interprets both their internal and their relational experiences. We conceptualize accelerators as contextual characteristics (i.e., occurring outside of the individual) that attach social meaning to ethnicity and race. We include accelerators in the framework to acknowledge that race and ethnicity are social constructs used to reinforce systems of power and oppression, upheld by social ideologies, policies, and structures that have favored White individuals categorically since the colonization of the U.S. Accelerators often manifest in the form of discrete events that prompt BIPOC individuals to examine or renegotiate their ERI. From this perspective, experiences of trauma, migration, and discrimination, and even normative life experiences, like puberty and becoming a parent, are significantly shaped by an individual’s race/ethnicity (e.g., Carter et al., 2017; Fox & Bruce, 2001). For example, Black American boys are viewed as threatening, and girls as sexually promiscuous, when they reach puberty; Latinx parents are regarded as having “anchor babies” to secure their residency status in the U.S. Our framework aims to elucidate the affective, behavioral, and cognitive responses that are triggered by accelerators across the lifespan - in the context of developmental enablers - and to advocate for interventions that would support the meaning-making necessary for positive ERI development (see Table 1 for a sampling of application ideas related to the content throughout this paper). To this end, we begin by describing each anchor through a developmental and contextual lens.

Table 1.

Practice Implications of the ERI A-B-C Framework

| Applications | Affective (A), Behavioral (B) and Cognitive (C) Goals | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Starting in Infancy | •Provide regular and positive intercultural experiences that expose babies to diverse caregivers and peers •Engage in ethnic-racial role behaviors within the family (e.g., celebrate traditions, discuss heroes, create cultural artifacts, cook traditional meals) •Facilitate play with diverse peers and multicultural toys, songs, videos, and books |

Prevent distress, fear, and inter-ethnic-racial group confusion through affiliation and intergroup contact (A) Build ethnic-racial behavioral competencies (B) Build awareness and knowledge of diverse ethnic- racial groups to minimize implicit biases (C) |

| Starting around Early Childhood | •Provide regular and positive intercultural experiences that expose children to diverse educators and peers at school •Provide opportunities for ethnic-racial role behaviors at school (e.g., celebrate traditions, discuss heroes, create cultural artifacts, eat traditional meals) •Provide bilingual education •Provide multicultural, group-based curriculums that normalize ethnic-racial differences and build acceptance of ethnic-racial groups •Provide opportunities for children to discuss and prepare for racialized experiences (e.g., discrimination) •Recognize and respond to the racialized experiences of children •Teach children about the historical context of race and ethnicity in the U.S. |

Promote a sense of comfort, safety and familiarity across ethnic-racial groups (A); Build diverse knowledge of inter-ethnic-racial group behavior to encourage seeing individual characteristics (and thereby reduce stereotyping) (C) Promote ethnic-racial pride (A); Build ethnic-racial behavioral competencies (B); Promote positive implicit cognitive associations between the self and school context to counteract stereotype threat (C) Build home language skills and promote strong family relationships (B) Build awareness and knowledge of diverse ethnic- racial groups (C); Scaffold positive inter-ethnic-racial group experiences (A,B) Validate a range of ethnic-racial feelings (A); Teach coping skills for negative ethnic-racial feelings and stereotype encounters (A/B/C); Teach positive ethnic-racial self-talk (C) Validate a range of ethnic-racial feelings (A); Teach coping skills for negative ethnic-racial feelings, and appraisal strategies for identifying stereotypes and discrimination (A/B/C); Teach positive ethnic-racial self-talk (C); Emphasize individual characteristics and growth mind-sets when discussing achievement (stereotype threat prevention) (C) Build knowledge and understanding of diverse ethnic-racial group experiences (C) |

| Starting around Middle Childhood | •Encourage friendship networks that include coethnic and diverse peers •Teach social and behavioral necessary for resisting by-stander effects and intervening in peer-based discrimination. •Scaffold children’s independent efforts for exploring their ERIs. •Acknowledge the complex (i.e., positive and negative) implications of race and ethnicity in historical and local context and teach about positionality |

Promote ethnic-racial pride (A); Build ethnic-racial behavioral competencies (B); Build acceptance of diverse ethnic-racial groups (C) Increase knowledge about intra- and inter-ethnic /racial group differences current-day peer experiences (C); Build competencies for empathy and restorative justice skills (A/B) Promote ethnic-racial pride (A); Build ethnic-racial behavioral competencies (B) Validate a range of ethnic-racial feelings (A); Teach coping skills for negative ethnic-racial feelings (A/B/C); Teach positive ethnic-racial self-and-other talk (C); Counteract race-based supremacy beliefs (C) |

| Starting around Adolescence | •Support independent efforts to understanding the meaning of their ERI •Promote positive interethnic and same-ethnic group friendships •Encourage critical dialogue about the historical and local context of race and ethnicity in the U.S. •Provide opportunities for activism |

Promote ethnic-racial affiliation, or sense of belonging (A) Provide supportive, positive opportunities to socialize and work alongside same and other- ethnic group peers (B) Build knowledge and understanding of diverse ethnic-racial group experiences (C) Build ethnic-racial behavioral competencies (B); Build opportunities for interethnic-racial group advocacy and friendships (A/B/C) |

| Starting around Adulthood | •Combat experiences of marginalization (e.g., tokenism, emotional labor, imposter syndrome) in higher education and work settings •Support parents in socializing their own children to race and ethnicity in the U.S. •Discuss integration of multiple social identities |

Build ethnic-racial behavioral competencies (B) Counteract self-stereotyping, reduce implicit biases (C); Create and maintain supportive and responsive systems to end systemic discriminatory policies and procedures (A/B/C) Promote ethnic-racial pride (A); Validate a range of ethnic-racial feelings (A); Build ethnic-racial behavioral competencies (B); Create community (online and offline) opportunities for positive intergenerational interethnic-racial group socialization (A/B/C) Promote consolidation of identity (C) Support self-awareness and counteract selfstereotyping across intersectional aspects of identity (A/B/C) Encourage continued ERI exploration in response to accelerators, with interpersonal support of meaning-making (A/B/C) |

THE “AS” – AFFECTIVE EXPERIENCES OF ERI ACROSS THE LIFESPAN

Current scholarship emphasizes positive ethnic-racial affect as a core component of ERI. According to traditional theories (Cross, 1991; Phinney & Ong, 2007; Sellers et al., 1997; Umaña-Taylor et al., 2004), positive ethnic-racial affect emerges as a result of exploration about one’s group membership and its meaning to one’s sense of self during adolescence. In this tradition, youth who feel happy and proud about their ERI are described as having achieved positive ethnic-racial affect, high private regard, group esteem, or affirmation (Rivas-Drake, Syed et al., 2014). A robust literature documents the benefits of positive ethnic-racial affect for the health and well-being of adolescents and young adults (Rivas-Drake, Syed et al., 2014). Notably, though, we break tradition with past theories of ERI to argue that ethnic-racial affect (a) emerges early in life as a leading and primary dimension of ERI; (b) manifests in various and complex ways across the lifespan; and (c) changes over developmental time and with context. These conceptual shifts are rooted in the Lifespan Model of ERI development (see Williams et al., in press). Importantly, accelerators and enablers are both relevant and essential to understanding the affective experiences of ERI development across the lifespan. Accelerators such as trauma and puberty, for example, introduce new emotional valence to individuals’ experiences, while enablers such as neuropriming and empathic abilities drive individuals’ affective responding.

Developmental Considerations

A lifespan perspective suggests that the affective component of ERI develops early with the help of neuropriming, perhaps even before ethnic-racial-specific cognitions and behaviors. Infants as young as 9 months show a nascent awareness of race and ethnicity such that familiar-race faces are more easily recognizable and preferable than unfamiliar-race faces (Telzer et al., 2013). Research is needed in this area to demonstrate the role of infants’ interethnic-racial awareness and affiliation, implicit socialization, and how these constructs relate to the early affective feelings of ERI.

The study of ethnic-racial affect during the preschool years (3- to 5-years old) has generally drawn on traditional developmental theories (e.g., social identity, cognitive developmental) to expand how children feel about the group(s) to which they belong relative to an “other group” (Bigler et al., 1997; Kowalski, 2003). According to this literature, both minority and majority preschool children develop the cognitive capacities to understand social categories and to affirm their own group memberships (Bigler et al., 2001; Nesdale & Flesser, 2001; Yee & Brown, 1992). In doing so, they tend to hold positive feelings about their ethnic-racial group and negative feelings about other groups (Aboud, 2003). Importantly, recent scholarship has challenged the assumption that preference for an ingroup is correlated with negative feelings for an outgroup (Marks et al., 2007) and questioned whether past findings are simply an artifact of the measures traditionally used in experimental studies (Kowalski, 2003); that is, children may hold positive views of ingroup and outgroups simultaneously, but when forced to choose between them tend to prefer ingroup members primarily.

Children in these early childhood ages are also capable of experiencing different or mixed emotions about the same stimulus or situation, introducing the possibility that children may feel both good and bad about their own ethnic-racial group (Phinney, 1991). At the same time, they begin to experience higher-level emotions such as empathy, pride, shame, guilt, and embarrassment – emotion experiences that are enabled by advances in theory of mind cognitive skills (Tangney & Fischer, 1995). Indeed, qualitative work suggests that preschool children hold relatively complex notions of ethnic-racial groups that are suggestive of underlying complex feelings (e.g., Seele, 2012). In one ethnographic study with a diverse sample of 3- and 4-year old children in a preschool classroom, Van Ausdale and Feagin (1996) describe how children used ethnic-racial group membership to include or exclude others, such as an incident in which a classmate moves away from a Black American boy, declaring that he is “stinky” because of his race. Though the study did not examine how this comment made the boy feel about his racial background, we may expect that such interactions give rise to ethnic-racial shame, anger, guilt, or embarrassment, at least for some children in some contexts. Research is also needed to understand the affective experiences of children who harass or name-call their peers based on ethnic-racial group membership.

ERI in the affective domain continues to deepen in complexity during middle childhood, and more scholarly attention has been given recently to understanding ERI in school-aged children (roughly ages 6–10 years). The primary focus of research at this developmental stage has been on ethnic-racial pride, which appears to be both common and increasing with age (e.g., Corenblum, 2014; Marks et al., 2007; Rogers et al., 2012). To be sure, as also demonstrated in earlier ages, not all children feel positively about their ethnic-racial group; feelings of ambivalence (Corenblum & Armstrong, 2012) and anxiety (Gillen-O’Neel et al., 2011) have also been found. A recent framework proposed by Dunbar et al. (2016) illustrates the nuanced emotional responses children may have regarding their ethnic-racial group. They posit that feelings of fear (e.g., to police presence), anger (e.g., about systems of oppression), and sadness (e.g., about personal experiences of discrimination) may co-exist alongside feelings of joy and pride in African-American children.

Adolescence (roughly ages 11–19) has long been the population of interest in studies of ERI. Across disciplines, theoretical orientations, and ethnic-racial populations, positive ethnic-racial affect, generally operationalized as feeling “happy,” “good,” or “proud,” is widely observed in studies with adolescents (Rivas-Drake et al., 2014). ERI pride has been delineated further across at least two dimensions that capture both private regard (i.e., how adolescents feel about themselves as a member of an ethnic group) and public regard (i.e., how adolescents believe others feel about their ethnic-racial groups; Hughes et al., 2011). However, scholars also recognize the need for a more in-depth understanding of ethnic-racial affect, particularly at this stage of development. Beyond feelings of pride, adolescents may also experience negative emotions such as ambivalence, fear, shame, anger, helplessness, and worthlessness with regards to their ethnic-racial group membership (Carter & Reynolds, 2011; Davis & Stevenson, 2006; Way et al., 2008). The work of Sue et al. (2007), for example, describes feelings such as self-doubt, powerlessness, and frustration engendered by everyday microaggressions directed at BIPOC individuals. Thus, regardless of an individual’s sense of pride and happiness as a person of color (i.e., affirmation), it is likely that minority group membership elicits negative feelings, even if only temporarily and sporadically and especially as one enters education or occupational settings that reflect social inequity or enable racism.

Some research suggests that adolescents may also simultaneously hold positive evaluations of themselves as members of an ethnic or racial group while also viewing their own group members negatively. Rogers and Way (Rogers & Way, 2016; Way et al., 2013; Way & Rogers, 2015) have shown how minority youth may denigrate their own group in this way. For example, Black American youth may describe other Black Americans as lazy, bad, and embarrassing, or Chinese immigrant youth may describe their Asian peers as weak and uncool, adopting society’s negative evaluations of their ethnic group and seeing themselves as positive “exceptions” to those negative evaluations. More research is needed on these potentially mixed emotional experiences, including the coping approaches most effective for working with negative emotions related to ERI experiences (see Anderson & Stevenson, 2019).

THE “BS” – BEHAVIORAL ASPECTS OF ERI ACROSS THE LIFESPAN

Throughout the lifespan, individuals engage in a range of behaviors, both implicitly (i.e., outside of conscious awareness) and explicitly (i.e., within conscious awareness), that reflect and contribute to ERI. In fact, all human behavior may be considered culturally-relevant and driven (Rogoff, 2003). For families of color, immigrant families, and other minority groups, ethnic-racial behaviors are more salient to the extent that they differ from those of majority populations. Food and dress, for example, are identified as culturally-specific only when they do not match mainstream cultural preferences and choices. Such ethnic-racial role behaviors may come to symbolize pride in and commitment to one’s ethnic-racial group, especially when enacted intentionally.

At the same time, such behaviors may serve to isolate and stereotype populations of color. Returning to the notion that ERI unfolds within established hierarchies of power, we also consider behavioral aspects of ERI that reflect the marginalized and oppressed experiences of ethnic-racial groups. As Ogbu has argued (2004), dominant group members stigmatize minority group behaviors in order to maintain a separateness, or boundary, between the majority identity group and the minority (see Cognitive section below on stereotypes and stigma). BIPOC individuals experience discrimination and oppression (noted as accelerators in our model) due to their ethnic-racial group membership, and these experiences prompt a range of behavioral responses. For example, in a study with Latinx college students, ethnic-racial discrimination predicted greater ERI, which led to more activism for their ethnic-racial group (Cronin et al., 2012). Others have noted that oppositional behaviors can be observed among marginalized groups as a way of pushing-back against the burden of being forced to conform behaviorally to the majority (i.e., White American) ways of doing things. A wide range of behaviors from language use, to religion, music, and social interactions have been governed and scripted by oppressive, dominant social groups with the intent of denigrating, separating, and oppressing minority groups politically, economically, and socially (see Ogbu, 2004). The enablers for behavioral experiences of ERI, then, are necessary for self-regulation, empathy, theory of mind, and other cognitive processes which support positive behavioral responding and activation in the context of challenging accelerators.

Developmental Considerations

Early in the life course, families are primary socialization agents when it comes to teaching children about their ethnic-racial background, (Hughes et al., 2006; Zayas & Solari, 1994). The effects of socialization, including parents’ explicit and intentional ethnic-racial socialization messages, can be seen as early as infancy, demonstrated by infants’ preferences for social stimuli that most closely resemble their home cultural environment (Corenblum, 2014; Rogers & Meltzoff, 2017; Rogers et al., 2012). This early exposure to social behaviors – such as accompanying a caregiver through daily routine chores, attending religious services with family members, and eating certain foods – provides young children with implicit knowledge about how people behave (Rogoff, 2003). Young children depend on the behavioral routines and environments of their families, learning what types of ethnic-racial role behaviors they themselves should engage in (including intersectional culture × gender-based behaviors) and what behaviors to expect from others in their social environments (Njoroge et al., 2009; Rogoff, 2003). For children speaking a language other than English at home, language use may become an important concrete behavioral manifestation of ethnic-racial group membership as well. For example, in a study of children of immigrants ages 6–12, Dominican-American children reported making social choices to speak Spanish in public so that passersby would identify them as Dominican, and not just as Black Americans (García Coll & Marks, 2009).

In adolescence, peers, schools, and community settings become increasingly important sources of opportunities for behavioral ERI exploration, with youth engaging in events outside the home that reflect their identification with their ethnic-racial group (Rivas-Drake et al., ; Umaña-Taylor, 2016). For example, in a daily diary study, Chinese-American adolescents reported higher levels of ERI salience on days in which they participated in culturally-relevant events (Yip & Fuligni, 2002). Similarly, when asked about their social group memberships, Puerto Rican youth mentioned participating in the Puerto Rican Pride parade as a reflection of their sense of belonging to this group (Way et al., 2008). Interestingly, research using social network analyses demonstrates how adolescent ERI-related behaviors become increasingly similar to that of their friends over time (Kornienko et al., 2015; Santos et al., 2017).

Research on ethnic-racial behaviors in adulthood has not been as prominent as during adolescence, but in this life stage, individuals may begin to think about the ways in which their distinct social group memberships and identities are interconnected (Umaña-Taylor et al., 2014). Young adults engage in conversation and ERI exploration to continue learning about their heritage (Syed & Azmitia, 2009). In addition, many adults become parents, and this new identity may motivate new ERI behaviors as parents seek to socialize their own children to their ethnic-racial group membership (Hughes et al., 2006; Juang et al., 2018; Marshall, 1995). In a study of Latinx multigenerational families, mothers’ ERI exploration predicted their socialization efforts with their adolescent daughters, who were also mothers themselves (Derlan et al., 2017a). Furthermore, when adolescent mothers entered young adulthood, their ERI predicted their children’s ethnic-racial identification, mediated by mothers’ socialization efforts (Derlan et al., 2017b). The process of engaging in culturally-specific behaviors appears to be passed on from one generation to the next, further validating a lifespan view of ERI development (Williams et al., in press).

THE “CS” – COGNITIVE ASPECTS OF ERI ACROSS THE LIFESPAN

The cognitive aspects of ERI include awareness (i.e., that individuals are grouped based on race and ethnicity), affiliation (i.e., that one belongs to a specific ethnic-racial group), attitudes (i.e., how important ethnic-racial group membership is to an individual), and knowledge (i.e., what it means to belong to an ethnic-racial group; Cuéllar et al., 1997; Negy et al., 2003; Phinney, 2000). In the study of ERI development, many of the most prominent measures used are based on cognitive representations of one’s ERI, including ethnic-racial labeling, public regard, identifications, salience, and centrality (e.g., Phinney, 2000; Sellers et al., 1997). Social scientists have also studied the emergence of biases, prejudices, stereotypes, and other cognitive biases reflecting racism and discrimination. ERI cognitions incorporate such biases and reflect an individuals’ understanding of who they are in relation to others, as defined by established social hierarchies that privilege White Americans over BIPOC and other minority groups. Such cognitions are enabled by many developmental processes, including essentialism, moral reasoning, language development, and theory of mind. Events such as migration, trauma, and new language acquisition accelerate the cognitive processes behind ERI consolidation, integration, and conversion.

Developmental Considerations

Though little research has explored ethnic-racial awareness in infancy, infants have been shown to recognize faces as early as two weeks after birth, and to show attentional gaze preference for their caregivers’ racial characteristics at eight months (Schneider & Ornstein, 2015). These implicit priming experiences contribute to young children’s abilities to understand fairness and equity, and to make social preferences based on those biases. For example, White American 15-month-old children participating in a study of fairness socially preferred a fair actor (who distributed toys in an equitable way), to an unfair actor - but only when the fair actor was also White. When the fair actor was Asian, the toddlers preferred the unfair White actor instead (Burns & Sommerville, 2014).

In early childhood, children continue their awareness of ethnic-racial group differences, begin to label individuals as belonging to ethnic-racial groups (theirs and others), and develop ethnic-racial knowledge, or the explicit understanding of the ethnic-racial role behaviors associated with their groups (Aboud, 1987; Bernal et al., 1990; Quintana & Vera, 1999). These ERI cognitions are often examined through the lens of social identity theory (Tajfel, 2010), which posits that individuals are motivated by the constant pursuit of a positive group identity (Hogg & Williams, 2000). Cognitive biases about one’s own and others’ ethnic-racial groups also develop during early childhood (Marks et al., 2015). Aronson (2004) found that children develop social theories to explain ingroup and outgroup behaviors, and they seek out information to support their theories.

Importantly, school-aged children engage in moral reasoning as they choose to include or exclude peers from ingroups and outgroups, and most children state that social exclusion is wrong (Rutland et al., 2010). In other words, most children are aware of inter-ethnic-racial group social differences, and typically espouse egalitarian values about inclusivity. At the same time, some children exclude peers based on social group ethnic-racial membership anyway, engaging in conventional reasoning strategies to justify their actions (e.g., “our team was full, so that is why we excluded them”). Importantly, the conventional excuses for excluding outgroup peers increase in complexity as children age, as situations become more contextually complex, and as resources become scarcer.

With the development of ethnic-racial biases, affiliation, and inter-ethnic-racial group attitudes in childhood and adolescence, children also demonstrate a more nuanced understanding of inter-ethnic-racial group differences over time, allowing them to challenge the cognitive biases, prejudices, and stereotypes they form (Bigler & Liben, 1993; Doyle & Aboud, 1995; Doyle et al., 1988). Still, children, adolescents, and adults can also come to define themselves in relation to negative ethnic stereotypes (Tajfel, 1981). Self-stereotyping, including stereotype threat and internalized racism, pose strong hazards to individuals’ well-being. In a recent study of elementary-aged children, African-American children who had prior awareness of stereotypes about African-American children’s lower performance on standardized tests showed poorer performance when they were given an evaluative exam. Academic performance on the exam was not hindered for students who had no prior awareness of the stereotype (Wasserberg, 2014).

Critically, the stereotype threat phenomenon (Steele & Aronson, 1995) does not hinge on internalized racism or believing the stereotype, but rather underscores the power of contextual cues and cognitive awareness to trigger it. For example, McKown and Weinstein (2003) found that minority children (6–10 years) with the cognitive awareness to infer racial stereotypes of others underperformed on an academic task, but only when it was primed as a diagnostic test through experimental manipulation (i.e., not without the prime). Thus, children were aware of the stereotype but not affected by it without a trigger. Similarly, Nasir et al. (2017) distinguished between “knowing versus believing” racial stereotypes, finding that African American and Latinx youth (4th–8th graders) who knew but rejected stereotypes were more academically engaged. Stereotype threat effects also intersect with immigrant generation stereotypes (e.g., that second-generation immigrants are less capable of academic achievement than their first-generation peers; Deaux et al., 2007).

In adolescence and adulthood, internalizing the negative biases and stereotypes about academic or job performance, physical ability, or other sources of achievement can have profoundly negative effects on individuals’ economic prospects and physical health (Aronson et al., 2013), demonstrating the need to help individuals counteract cognitive biases they may form based on stereotypes. Among college students, resisting stereotype threat is associated with positive academic outcomes, and intervening by providing identity supports for African American students has shown improvements in cognitive testing scores (Nadler & Komarraju, 2016; Owens & Lynch, 2012). As a whole, studies across the lifespan underscore the relevance, context dependency, and complexity of cognitive processes underlying ERI.

IMPLICATIONS FOR INTERVENTION: APPLYING THE A-B-C FRAMEWORK

Our approach of unpacking the affective, behavioral, and cognitive components of ERI aligns with a rich history of psychological theory and intervention. Specifically, evidence supports the effectiveness of targeting thoughts, feelings, and behaviors to address a wide range of psychosocial and educational needs (e.g., Van Dis et al., 2020). Despite this promise, traditional programming has fallen short of addressing the unique lived experiences of minoritized groups. Interventions that promote ERI naturally, and with “conscious engagement,” align with individuals’ values, beliefs, norms, customs, and behaviors, and can lead to improvement in youths’ critical consciousness and intergroup bias reduction (Rivas-Drake & Umaña-Taylor, 2019, p. 214). Moreover, a focus on ERI acknowledges the realities of minority individuals and groups through a strengths-based lens to promote well-being, while the emphasis on meaning-making embedded within established social hierarchies acknowledges the systemic and oppressive forces that shape an individual’s ERI. In short, we see tremendous potential for enhancing the appeal and efficacy of programs by marrying well-established traditional approaches to intervention (i.e., A-B-C models) with careful consideration for the lived experiences of BIPOC individuals with the ultimate goal of promoting ERI development.

An A-B-C heuristic aims to enable practitioners, researchers, and educators to apply ERI theory to educational and psychosocial curricula and intervention, including those targeting anxiety and depression among individuals from marginalized groups (Cooley-Strickland et al., 2011). We argue for the importance and value of attending to the ERI affective, behavioral, and cognitive components separately and in concert; we highlight accelerators and enablers of ERI development in the model so that educators and practitioners can be better attuned to—and appropriately react to—the factors that may positively or negatively influence ERI development and consolidation; and we conceptualize meaning-making as a process that can be scaffolded and supported starting in infancy and throughout the lifespan.

Our tripartite model provides a quick, palatable infographic for practitioners, researchers and educators. For example, children can be provided with helpful affective, behavioral, and cognitive exercises and experiences that may facilitate a positive ERI exploration process and later consolidation in adolescence/adulthood. For those working with adolescents, understanding how the A-B-Cs each are uniquely influenced by puberty, social contexts, and adolescents’ growing awareness of societal systems may facilitate adaptive responding to experiences of discrimination and other challenges of inequity. The framework can serve as a heuristic for parents to support meaning-making processes at home (again, starting in infancy) through the ERI socialization processes that have been discussed above. Educators, who themselves serve as agents of socialization (Priest et al., 2014), may use the tripartite model as a guide to facilitate ERI in developmentally appropriate and concrete ways in schools (i.e., grade- or school-wide), considering that school experiences influence ERI (Smith et al., 2003). In adulthood, integrating ERI with other aspects of identity in response to oppressive sociopolitical climates or policy changes may be an important task that could be facilitated by using the A-B-C framework in a counseling setting.

We reiterate that feelings, thoughts, and behaviors do not occur in isolation and must be considered in light of issues of social positionality and historical context. As articulated in (Williams et al., in press), we caution against assumptions regarding what constitutes a “healthy” ERI, and encourage practitioners to explore the most meaningful and adaptive ways in which a given individual might approach their race-ethnicity. In other words, ERI may best be understood as a constellation of positive and negative experiences that develop over the lifespan and shift across time and situation. Our perspective is consistent with the concept of dynamism and recognizes ERI as a malleable factor that may be targeted in intervention (Kaplan & Garner, 2017). Ideas for specific A-B-C related intervention elements – many of which can be applied in both individual and group (e.g., school, community) settings – appear in Table 1 below.

To support and optimize the A-B-C experiences of ERI across the lifespan, educators, practitioners, and researchers must attend to them in context. Here, we emphasize the role of meaning-making to draw forward the person-context interaction, and describe how meaning-making promotes self- and other-oriented narratives that will ultimately contribute to ERI exploration and consolidation across the lifespan. These narratives are an essential way of testing and forming beliefs about ERI and processing difficulties – including trauma – related to identity consolidation. Narratives can be reinforced, explored, and supported through writing (e.g., journaling both on and offline), school-based cultural fairs and sharing opportunities, community story-telling events and gatherings, counseling/therapy, and many more modalities (McLean, 2005; Syed & Azmitia, 2008).

Synthesizing A-B-C Intervention Elements into Psychosocial Programming

Scholars have already begun synthesizing ERI-related A-B-C activities such as those found in Table 1 with meaning-making practices that promote diverse individuals’ well-being (see review by Jones & Neblett, 2016). In a recent framework for responding adaptively to discrimination, Anderson and Stevenson (2019) presented the RECAST (Racial Encounter Coping Appraisal Socialization Theory) theory to support African-American youth and families in facing racism and race-related trauma. This model combines aspects of behavioral and cognitive elements of the ERI A-B-C’s, focusing on racial coping skills (including reappraisal, decision-making, and resolution of the discriminatory experience), family socialization practices and behaviors, and cognitive understanding of self-efficacy to promote positive outcomes related to identity and psychological, academic, and social well-being. The authors explain how these activities can then be applied in cognitive-behavioral therapy settings to promote cognitive restructuring in ways that will form positive self-beliefs and self-efficacy.

Another recent intervention, the Identity Project, drew specifically from much of the ERI theory and research presented in this paper and in the Lifespan Model paper (Williams et al., in press) in combination with a universal mental health promotion approach to promoting ERI exploration and consolidation (Umaña-Taylor, Kornienko et al., 2018). In this intervention, Umaña-Taylor and colleagues take a multicultural approach to promote positive ERI development among adolescents from all ethnic-racial backgrounds, focusing on identity consolidation, or the meaning-making necessary to integrate a sense of self as one currently is, with an identity one hopes to become (Erikson, 1968). Using a randomized controlled design, the intervention showed positive effects not only on promoting ERI consolidation, but also in promoting positive psychosocial well-being outcomes, including increased self-esteem and improved academic grades.

As most of the extant ERI-related interventions have been developed for and used with adolescents and young adults, new intervention approaches for use across the entire lifespan are sorely needed. In alignment with (Williams et al., in press), we also recognize the limitations of operationalizing and measuring positive ERI in terms of academic performance and individual-level psychological well-being. For example, positive ERI outcomes might include a more critical reflection on structural inequality, as critical consciousness (Diemer et al., 2015) has been shown to have complex relationships with normative indicators of academic adjustment and well-being (e.g., Godfrey et al., 2019). We encourage intervention work that broadens the scope of the outcomes ERI may promote.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Ample research suggests that when individuals engage in ERI exploration and consolidation, and are able to make meaning of those experiences for positive self and other-oriented relationships, well-being is amplified. These implications are wide and diverse. For example, health protective outcomes resulting from positive identity development include healthy eating, increased physical activity, decreased cardiovascular risk, and lower incidence of pulmonary disease (e.g., Clark & Gochett, 2006; Fuller-Rowell et al., 2012). Behaviorally, adolescents and adults alike show lower rates of substance use, sexual risk taking, engagement in violence, and other risk behaviors when they experience more positive ERI development (e.g., Alderete et al., 2012; Marsiglia et al., 2001). Other individual-level outcomes of promoting positive ERI development include higher self-esteem, greater compassion, academic/occupational achievement, and personal resiliency (see Armenta & Hunt, 2009; Umaña-Taylor & Updegraff, 2007; Wong et al., 2003).

At the group level, promoting positive ERI is related to increased inter-ethnic and racial group harmony, greater awareness of and disruption of race-based hierarchy and systems of power, activism, and therefore policy change. For example, a study of early adolescents in the UK documented the impact of increased interethnic group contact for promoting empathy, cultural openness, and decreasing interethnic group biases (Abbott & Cameron, 2014). These positive effects of interethnic group contact, in turn, helped to promote heightened intentionality for intervening in an ethnic-based bullying scenario. In fact, the lack of attention to positive ERI development, particularly among individuals whose positionality in oppressive systems favors them as individuals with power, is responsible for the maintenance of oppressive practices, systemic racism, and race/ethnicity-based policies (e.g., the Patriot Act; see Pitt (2011). We encourage scholars and practitioners to widely apply the A-B-C framework to group-level processes and explore how understanding its components might benefit not only individuals, but also boost positive intergroup relationships.

Whereas the focus of this paper has primarily highlighted the outcomes of ERI across affective, behavioral, and cognitive domains for minoritized youth, ERI development is also relevant for White American youth (see Helms, 1990). Most ERI literature focuses exclusively on ethnic-racial minority group members’ development. Although this is understandable given the oppressive, racist systems that lead to the social construction of ethnic-racial groups in the U.S. to begin with, continuing this research practice could perpetuate an assumption that ethnicity and race are not also salient constructs to White American youths’ identities. We therefore urge future research and intervention to consider the unique contexts of White American youths’ ERI development, building from Critical Race Theory (CRT), to prevent the perpetuation of White American “perspectivelessness” about racism and marginalization that is indicative of White American privilege and allows cycles of systemic racism to continue (Harris, 2012; Moffitt et al., under review).

Although historically thought of as being “cultureless,” there are important implications and outcomes for ERI exploration and subsequent consolidation in youth who identify as White (Perry, 2001). These outcomes can follow at least two directions. The first is a more positive, consolidated identity within an ERI paradigm that posits all youth—ethnic minority or otherwise—undergo similar processes of ERI development and experience positive outcomes. Research suggests, for example, that integrating CRT into schools by encouraging ethnic-racial identity discussions among all students can foster ERI as real and decrease ethnocentrism in majority youth (Ladson-Billings & Tate, 2016). The second is routed toward the development of a supremist identity, claiming White identity as superior to others and the identity standard to which all others should be judged (Perry, 2001). Although understudied, the development of White American identities in youth, including supremist ideologies, is an important area for future research. According to the Southern Poverty Law Center, there were 954 hate groups in the U.S. as of 2017, a 22% increase from 2014. This percentage encompasses all supremacist groups, but the rise in total neo-Nazi and other White supremacist groups specifically increased by 22% in 2017. Studying ERI development, particularly processes of meaning-making, accelerators, and enablers, will be an important future direction when considering both positive and supremist White identity development. It will also be important to consider the developmental processes of understanding privilege and oppression among White youth and their subsequent impacts on the A-B-Cs of ERI development.

CONCLUSION

In sum, the tripartite framework offers a heuristic for how to best identify the needs and optimal points of intervention for individuals’ ERI, with the end goal of positive adjustment. The framework can be broadly applied with individuals from varied ethnic/racial backgrounds (while attending to important individual differences) across educational and therapeutic settings and takes into account age-graded developmental considerations as well as sociohistorical contextual factors that inform the meaning-making process and the implications of ERI for individuals and their views of others across the lifespan. It is our hope that this paper initiates a discourse that puts ERI theories, empirical literature, and practitioners in closer conversation with one another.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

FUNDING

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 1729711.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

We use the term “minority” in this paper to indicate a social group or its member that has been historically marginalized or oppressed, and therefore has relatively less social, political, or economic power than the “majority” group or individual. Minority therefore does not mean the group is small in number, but rather that it does not share equal social, political, or economic power with the majority.

Contributor Information

Amy K. Marks, Suffolk University

Esther Calzada, University of Texas at Austin.

Lisa Kiang, Wake Forest University.

María C. Pabón Gautier, St. Olaf College

Stefanie Martinez-Fuentes, Arizona State University.

Nicole R. Tuitt, University of California-Berkeley

Kida Ejesi, Boston Children’s Hospital/Harvard Medical School.

Leoandra Onnie Rogers, Northwestern University.

Chelsea Derlan Williams, Virginia Commonwealth University.

Adriana Umaña-Taylor, Harvard University.

REFERENCES

- Abbott N, & Cameron L (2014). What makes a young assertive bystander? The effect of intergroup contact, empathy, cultural openness, and in-group bias on assertive bystander intervention intentions. Journal of Social Issues, 70(1), 167–182. 10.1111/josi.12053 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aboud FE (1987). The development of ethnic self-identification and attitudes. In Phinney J & Rotheram M (Eds.), Children’s ethnic socialization: Pluralism and development. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Aboud FE (2003). The formation of in-group favoritism and out-group prejudice in young children: Are they distinct attitudes? Developmental Psychology, 39(1), 48–60. 10.1037/0012-1649.39.1.48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldana A, & Byrd C (2015). School ethnic-racial socialization: Learning about race and ethnicity among African American students. Urban Review, 47(3), 563–576. 10.1007/s11256-014-0319-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alderete E, Monteban M, Gregorich S, Kaplan CP, Mejía R, & Pérez-Stable EJ (2012). Smoking and exposure to racial insults among multiethnic youth in Jujuy, Argentina. Cancer Causes & Control, 23(1), 37–44. 10.1007/s10552-012-9906-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RE, & Stevenson HC (2019). RECASTing racial stress and trauma: Theorizing the healing potential of racial socialization in families. American Psychologist,74(1), 63–75. 10.1037/amp0000392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armenta BE, & Hunt JS (2009). Responding to societal devaluation: Effects of perceived personal and group discrimination on the ethnic group identification and personal self-esteem of Latino/Latina adolescents. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 12(1), 23–39. 10.1177/1368430208098775 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aronson J (2004). The threat of stereotype. Educational Leadership, 62(3), 14–20. http://www.ascd.org/publications/educational-leadership/nov04/vol62/num03/The-Threat-of-Stereotype.aspx [Google Scholar]

- Aronson J, Burgess D, Phelan SM, & Juarez L (2013). Unhealthy interactions: The role of stereotype threat in health disparities. American Journal of Public Health, 103(1), 50–56. 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernal ME, Knight GP, Garza CA, Ocampo KA, & Cota MK (1990). The development of ethnic identity in Mexican-American children. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 12(1), 3–24. 10.1177/07399863900121001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bigler RS, Brown CS, & Markell M (2001). When groups are not created equal: Effects of group status on the formation of intergroup attitudes in children. Child Development, 72(4), 1151–1162. 10.1111/1467-8624.00339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigler RS, Jones LC, & Lobliner DB (1997). Social categorization and the formation of intergroup attitudes in children. Child Development, 68(3), 530–543. 10.2307/1131676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigler RS, & Liben LS (1993). A cognitive-developmental approach to racial stereotyping and reconstructive memory in Euro-American children. Child Development, 64(5), 1507–1518. 10.2307/1131549 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Branscombe NR, Schmitt MT, & Harvey RD (1999). Perceiving pervasive discrimination among African Americans: Implications for group identification and well-being. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 77 (1), 135–149. 10.1037/0022-3514.77.1.135 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burns MP, & Sommerville JA (2014). “I pick you”: The impact of fairness and race on infants’ selection of social partners. Frontiers in Psychology, 5(93), 1–10. 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter R, Seaton EK, & Rivas-Drake D (2017). Racial identity in the context of pubertal development: Implications for adjustment. Developmental Psychology, 53(11), 2170–2181. 10.1037/dev0000413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter RT, & Reynolds AL (2011). Race-related stress, racial identity status attitudes, and emotional reactions of Black Americans. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 17(2), 156–162. 10.1037/a0023358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark R, & Gochett P (2006). Interactive effects of perceived racism and coping responses predict a school-based assessment of blood pressure in Black youth. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 32(1), 1–9. 10.1207/s15324796abm3201_1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooley-Strickland MR, Griffin RS, Darney D, Otte K, & Ko J (2011). Urban African American youth exposed to community violence: A school-based preventative intervention efficacy study. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community, 39(2), 149–166. 10.1080/10852352.2011.556573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corenblum B (2014). Relationships between racial–ethnic identity, self-esteem and in-group attitudes among first nation children. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43(3), 387–404. 10.1007/s10964-013-0081-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corenblum B, & Armstrong HD (2012). Racial-ethnic identity development in children in a racial-ethnic minority group. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 44(2), 124–137. 10.1037/a0027154 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw K (1989). Demarginalizaing the intersection of race and sex: A Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1(8), 139–167. http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol1989/iss1/8 [Google Scholar]

- Cronin TJ, Levin S, Branscombe NR, van Laar C, & Tropp LR (2012). Ethnic identification in response to perceived discrimination protects well-being and promotes activism: A longitudinal study of Latino college students. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 15(3), 393–407. 10.1177/1368430211427171 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cross WE Jr. (1991). Shades of Black: Diversity in African-American identity. Temple University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cuéllar I, Nyberg B, Maldonado RE, & Roberts RE (1997). Ethnic identity and acculturation in a young adult Mexican-origin population. Journal of Community Psychology, 25(6), 535–549. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davis GY, & Stevenson HC (2006). Racial socialization experiences and symptoms of depression among Black youth. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 15(3), 293–307. 10.1007/s10826-006-9039-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deaux K, Bikmen N, Gilkes A, Ventuneac A, Joseph Y, Payne YA, & Steele CM (2007). Becoming American: Stereotype threat effects in Afro-Caribbean immigrant groups. Social Psychology Quarterly, 70(4), 384–404. 10.1177/019027250707000408 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Derlan CL, Umaña-Taylor AJ, Updegraff KA, & Jahromi LB (2017a). Mothers’ characteristics as predictors of adolescents’ ethnic–racial identity: An examination of Mexican-origin teen mothers. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 22(3), 453–459. 10.1037/cdp0000072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derlan CL, Umaña-Taylor AJ, Updegraff KA, & Jahromi LB (2017b). Longitudinal relations among Mexican-origin mothers’ cultural characteristics, cultural socialization, and 5-year-old children’s ethnic–racial identification. Developmental Psychology, 53(11), 2078–2091. 10.1037/dev0000386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diemer MA, McWhirter EH, Ozer EJ, & Rapa LJ (2015). Advances in the conceptualization and measurement of critical consciousness. The Urban Review, 47(5), 809–823. 10.1007/s11256-015-0336-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle AB, & Aboud FE (1995). A longitudinal study of White children’s racial prejudice as a social-cognitive development. Merrill Palmer Quarterly, 41(2), 209–228. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle AB, Beaudet J, & Aboud F (1988). Developmental patterns in the flexibility of children’s ethnic attitudes. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 19(1), 3–18. 10.1177/0022002188019001001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar AS, Leerkes EM, Coard SI, Supple AJ, & Calkins S (2016). An integrative conceptual model of parental racial/ethnic and emotion socialization and links to children’s social-emotional development among African American families. Child Development Perspectives, 11(1), 16–22. 10.1111/cdep.12218 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis A (1955). New approaches to psychotherapy techniques. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 11(3), 207–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH (1968). Identity, youth and crisis. W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Fox GL, & Bruce C (2001). Conditional fatherhood: Identity theory and parental investment theory as alternative sources of explanation of fathering. Journal of Marriage and Family, 63(2), 394–403. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org.ezproxysuf.flo.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00394.x [Google Scholar]

- Fuller-Rowell TE, Evans GW, & Ong AD (2012). Poverty and health: The mediating role of perceived discrimination. Psychological Science, 23(7), 734–739. 10.1177/0956797612439720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García Coll C, & Marks AK (2009). Immigrant stories: Ethnicity and academics in middle childhood. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gillen-O’Neel C, Ruble DN, & Fuligni AJ (2011). Ethnic stigma, academic anxiety, and intrinsic motivation in middle childhood. Child Development, 82(5), 1470–1485. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01621.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey EB, Santos CE, & Burson E (2019). For better or worse? System-justifying beliefs in sixth-grade predict trajectories of self-esteem and behavior across early adolescence. Child Development, 90(1), 180–195. 10.1111/cdev.12854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding JF, Hughes DL, & Way N (2017). Racial/Ethnic differences in mothers’ socialization goals for their adolescents. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 23(2), 281–290. 10.1037/cdp0000116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris AP, Crenshaw K, Gotanda N, Peller G, & Thomas K (2012). Critical race theory. International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Helms JE (Ed.). (1990). Contributions in Afro-American and African studies, No. 129. Black and White racial identity: Theory, research, and practice. Greenwood Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hogg MA, & Williams KD (2000). From I to we: Social identity and the collective self. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 4(1), 81–97. 10.1037/1089-2699.4.1.81 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Rodriguez J, Smith EP, Johnson DJ, Stevenson HC, & Spicer P (2006). Parents’ ethnic-racial socialization practices: A review of research and directions for future study. Developmental Psychology, 42(5), 747–770. 10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Way N, & Rivas-Drake D (2011). Stability and change in private and public ethnic regard among African American, Puerto Rican, Dominican, and Chinese American early adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21(4), 861–870. 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2011.00744.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones SC, & Neblett EW (2016). Racial–ethnic protective factors and mechanisms in psychosocial prevention and intervention programs for Black youth. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 19(2), 134–161. 10.1007/s10567-016-0201-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juang LP, Park I, Kim SY, Lee RM, Qin D, Okazaki S, Swartz TT, & Lau A (2018). Reactive and proactive ethnic–racial socialization practices of second-generation Asian American parents. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 9(1), 4–16. 10.1037/aap0000101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan A, & Garner JK (2017). A complex dynamic systems perspective on identity and its development: The dynamic systems model of role identity. Developmental Psychology, 53(11), 2036–2051. 10.1037/dev0000339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornienko O, Santos CE, & Updegraff K (2015). Friendship networks and ethnic-racial identity development: Contributions of social network analysis. In Santos CE & Umaña-Taylor AJ (Eds.), Studying ethnic identity: Methodological advances and considerations for future research(pp. 177–202). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski K (2003). The emergence of ethnic and racial attitudes in preschool-aged children. Journal of Social Psychology, 143(6), 677–690. 10.1080/00224540309600424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladson-Billings G, & Tate WF (2016). Toward a critical race theory of education. In Critical race theory in education (pp. 10–31). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Marks AK, Ejesi K, McCullough M, & Garcia Coll C (2015). The development and implications of racism and discrimination. In Lamb M, Garcia Coll C, & Lerner R (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology and developmental science: Vol. 3: Socioemotional processes (7th ed., pp.324–365). John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Marks AK, Szalacha LA, Lamarre M, Boyd MJ, & García Coll C (2007). Emerging ethnic identity and interethnic group social preferences in middle childhood: Findings from the Children of Immigrants Development in Context (CIDC) study. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 31(5), 501–513. 10.1177/0165025407081462 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall S (1995). Ethnic socialization of African American children: Implications for parenting, identity development, and academic achievement. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 24(4), 377–396. 10.1007/BF01537187 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglia FF, Kulis S, & Hecht ML (2001). Ethnic labels and ethnic identity as predictors of drug use among middle school students in the Southwest. Journal of Research on Adolescence,11(1), 21–48. 10.1111/1532-7795.00002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McKown C, & Weinstein RS (2003). The development and consequences of stereotype consciousness in middle childhood. Child Development, 74(2), 498–515. 10.1111/1467-8624.7402012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean KC (2005). Late adolescent identity development: Narrative meaning making and memory telling. Developmental Psychology, 41(4), 683–691. 10.1037/0012-1649.41.4.683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt U, Rogers LO, & Dastrup K (under review). White identity development among White children: An application of Helms’ White Racial Identity Development model.

- Motti-Stefanidi F, & Masten AS (2017). A resilience perspective on immigrant youth adaptation and development. In Cabrera N & Leyendecker B (Eds.), Handbook on positive development of minority children and youth (p. 19–34). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Nadler DR, & Komarraju M (2016). Negating stereotype threat: Autonomy support and academic identification boost performance of African American college students. Journal of College Student Development, 57(6), 667–679. 10.1353/csd.2016.0039 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nasir NIS, McKinney de Royston M, O’Connor K, & Wischnia S (2017). Knowing about racial stereotypes versus believing them. Urban Education, 52(4), 491–524. 10.1177/0042085916672290 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Negy C, Shreve TL, Jensen BJ, & Uddin N (2003). Ethnic identity, self-esteem, and ethnocentrism: A study of social identity versus multicultural theory of development. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 9(4), 333–344. 10.1037/1099-9809.9.4.333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesdale D, & Flesser D (2001). Social identity and the development of children’s group attitudes. Child Development, 72(2), 505–517. 10.1111/1467-8624.00293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Njoroge W, Benton T, Lewis ML, & Njoroge NM (2009). What are infants learning about race? A look at a sample of infants from multiple racial groups. Infant Mental Health Journal: Official Publication of the World Association for Infant Mental Health, 30(5), 549–567. 10.1002/imhj.20228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogbu JU (2004). Collective identity and the burden of “Acting White” in Black history, community, and education. The Urban Review, 36(1), 1–35. 10.1023/B:URRE.0000042734.83194.f6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Owens J, & Lynch SM (2012). Black and Hispanic immigrants’ resilience against negative-ability racial stereotypes at selective colleges and universities in the United States. Sociology of Education, 85(4), 303–325. 10.1177/0038040711435856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry P (2001). White means never having to say you’re ethnic. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 31(1), 56–91. 10.1177/089124101030001002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS (1991). Ethnic identity and self-esteem: A review and integration. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 13(2), 193–208. 10.1177/07399863910132005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS (2000). Ethnic and racial identity: Ethnic identity. In Kazdin AE (Ed.), Encyclopedia of psychology (Vol. 3, pp. 254–259). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS, & Ong AD (2007). Conceptualization and measurement of ethnic identity: Current status and future directions. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 54(3), 271–281. 10.1037/0022-0167.54.3.271 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pitt C (2011). US Patriot Act and Racial Profiling: Are there consequences of discrimination? Michigan Sociological Review, 25, 53–69. [Google Scholar]

- Priest N, Walton J, White F, Kowal E, Baker A, & Paradies Y (2014). Understanding the complexities of ethnic-racial socialization processes for both minority and majority groups: A 30-year systematic review. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 43, 139–155. 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2014.08.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Quintana SM, & Vera EM (1999). Mexican American children’s ethnic identity, understanding of ethnic prejudice, and parental ethnic socialization. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 21(4), 387–404. 10.1177/0739986399214001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rivas-Drake D, Seaton EK, Markstrom C, Quintana S, Syed M, Lee RM, Schwartz SJ, Umaña-Taylor AJ, French S, Yip T, & Ethnic and Racial Identity in the 21st Century Study Group. (2014). Ethnic and racial identity in adolescence: Implications for psychosocial, academic, and health outcomes. Child Development, 85(1), 40–57. 10.1111/cdev.12200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivas-Drake D, Syed M, Umaña-Taylor A, Markstrom C, French S, Schwartz SJ, Lee R, & Ethnic and Racial Identity in the 21st Century Study Group. (2014). Feeling good, happy, and proud: A meta-analysis of positive ethnic-racial affect and adjustment. Child Development, 85(1), 77–102. 10.1111/cdev.12175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivas-Drake D, & Umaña-Taylor AJ (2019). Below the surface: Talking with teens about race, ethnicity, and identity. Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers LO, & Meltzoff AN (2017). Is gender more important and meaningful than race? An analysis of racial and gender identity among Black, White, and mixed-race children. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology,23(3), 323–334. 10.1037/cdp0000125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers LO, & Way N (2016). “I have goals to prove all those people wrong and not fit into any one of those boxes” paths of resistance to stereotypes among Black adolescent males. Journal of Adolescent Research, 31(3), 263–298. 10.1177/0743558415600071 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers LO, Zosuls KM, Halim ML, Ruble D, Hughes D, & Fuligni A (2012). Meaning making in middle childhood: An exploration of the meaning of ethnic identity. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 18 (2), 99–108. 10.1037/a0027691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogoff B (2003). The cultural nature of human development. Oxford university press. [Google Scholar]

- Rutland A, Killen M, & Abrams D (2010). A new social-cognitive developmental perspective on prejudice: The interplay between morality and group identity. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 5(3), 279–291. 10.1177/1745691610369468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos CE, Kornienko O, & Rivas-Drake D (2017). Peer influence on ethnic-racial identity development: A multi-site investigation. Child Development, 88(3), 725–742. 10.1111/cdev.12789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider W, & Ornstein PA (2015). The development of children’s memory. Child Development Perspectives, 9 (3), 190–195. 10.1111/cdep.12129 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seele C (2012). Ethnicity and early childhood. International Journal of Early Childhood, 44(3), 307–325. 10.1007/s13158-012-0070-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Rowley SAJ, Chavous TM, Shelton JN, & Smith MA (1997). Multidimensional inventory of Black identity: A preliminary investigation of reliability and construct validity. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 73(4), 805–815. 10.1037/0022-3514.73.4.805 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Smith MA, Shelton JN, Rowley, Stephanie AJ., & Chavous TM (1998). Multidimensional Model of Racial Identity: A Reconceptualization of African American Racial Identity. Personality and Social Psychology Review,2(1), 18–39 10.1207/s15327957pspr0201_2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semaj L (1980). The development of racial evaluation and preference: A cognitive approach. Journal of Black Psychology, 6(2), 59–79. 10.1177/009579848000600201 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sheets RH (Ed.). (1999). Racial and ethnic identity in school practices: Aspects of human development. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Smith EP, Atkins J, & Connell CM (2003). Family, school, and community factors and relationships to racial–ethnic attitudes and academic achievement. American Journal of Community Psychology, 32(1–2), 159–173. 10.1023/A:1025663311100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southern Poverty Law Center. (2107, Spring). Hate groups.

- Spencer MB (1995). Old issues and new theorizing abut African American youth: A phenomenological variant of ecological systems theory. In Taylor RL (Ed.), Black youth: Perspectives on their status in the United States (pp. 37–69). Westport, CT: Praeger. [Google Scholar]

- Steele CM, & Aronson J (1995). Stereotype threat and the intellectual test performance of African Americans. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,69(5), 797–811. 10.1037/0022-3514.69.5.797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sue DW, Capodilupo CM, Torino GC, Bucceri JM, Holder A, Nadal KL, & Esquilin M (2007). Racial microaggressions in everyday life: Implications for clinical practice. American Psychologist, 62(4), 271–286. 10.1037/0003-066X.62.4.271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syed M, & Azmitia M (2008). A narrative approach to ethnic identity in emerging adulthood: Bringing life to the identity status model. Developmental Psychology, 44(4), 1012–1027. 10.1037/0012-1649.44.4.1012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syed M, & Azmitia M (2009). Longitudinal trajectories of ethnic identity during the college years. Journal of Research on Adolescence,19(4), 601–624. 10.1111/jora.2009.19. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel H (1981). Human groups and social categories: Studies in social psychology. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tangney JPE, & Fischer KW (Eds.). (1995). Self-conscious emotions: The psychology of shame, guilt, embarrassment, and pride. Gulliford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Telzer EH, Flannery J, Shapiro M, Humphreys KL, Goff B, Gabard-Durman L, Gee DD, & Tottenham N (2013). Early experience shapes amygdala sensitivity to race: An international adoption design. Journal of Neuroscience, 33(33), 13484–13488. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1272-13.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tukachinsky R (2015). Where we have been and where we can go from here: Looking to the future in research on media, race, and ethnicity. Journal of Social Issues, 71(1), 186–199. [Google Scholar]

- Turner JC (2010). Social categorization and the self-concept: A social cognitive theory of group behavior. In Postmes T &Branscombe NR (Eds.), Key readings in social psychology. Rediscovering social identity (p. 243–272). Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ (2016). A post-racial society in which ethnic-racial discrimination still exists and has significant consequences for youths’ adjustment. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 25(2), 111–118. 10.1177/0963721415627858 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Douglass S, Updegraff KA, & Marsiglia F (2018). Small-scale randomized efficacy trial of the identity project: Promoting adolescents’ ethnic-racial identity exploration and resolution. Child Development, 89 (3), 862–870. 10.1111/cdev.12755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Kornienko O, Bayless SD, & Updegraff KA (2018). A universal intervention program increases ethnic-racial identity exploration and resolution to predict adolescent psychosocial functioning one year later. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 47(1), 1–15. 10.1007/s10964-017-0766-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Quintana SM, Lee RM, Cross WE Jr., Rivas-Drake D, Schwartz SJ, Syed M, Yip T, Seaton E, & Ethnic and Racial Identity in the 21st Century Study Group. (2014). Ethnic and racial identity during adolescence and into young adulthood: An integrated conceptualization. Child Development, 85(1), 21–39. 10.1111/cdev.12196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, & Updegraff KA (2007). Latino adolescents’ mental health: Exploring the interrelations among discrimination, ethnic identity, cultural orientation, self-esteem, and depressive symptoms. Journal of Adolescence, 30(4), 549–567. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Yazedjian A, & Bámaca-Gómez M (2004). Developing the ethnic identity scale using Eriksonian and social identity perspectives. Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research, 4(1), 9–38. 10.1207/S1532706XID0401_2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]