Abstract

The surface M protein of group A streptococci (GAS) is one of the major virulence factors for this pathogen. Antibodies to the M protein can facilitate opsonophagocytosis by phagocytic cells present in human blood. We investigated whether pooled normal immunoglobulin G (IVIG) contains antibodies that can opsonize and enhance the phagocytosis of type M1 strains of GAS and whether the levels of these antibodies vary for different IVIG preparations. We focused on the presence of anti-M1 antibodies because the M1T1 serotype accounts for the majority of recent invasive GAS clinical isolates in our surveillance studies. The level of anti-M1 antibodies in three commercial IVIG preparations was determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), and the opsonic activity of these antibodies was determined by neutrophil-mediated opsonophagocytosis of a representative M1T1 isolate. High levels of opsonic anti-M1 antibodies were found in all IVIG preparations tested, and there was a good correlation between ELISA titers and opsonophagocytic activity. However, there was no significant difference in the levels of opsonic anti-M1 antibodies among the various IVIG preparations or lots tested. Adsorption of IVIG with M1T1 bacteria removed the anti-M1 opsonic activity, while the level of anti-M3 opsonophagocytosis was unchanged. Plasma was obtained from seven patients with streptococcal toxic shock syndrome who received IVIG therapy, and the level of anti-M1 antibodies was assessed before and after IVIG administration. A significant increase in the level of type M1-specific antibodies was found in the plasma of all patients who received IVIG therapy (P < 0.006). The results reveal another potential mechanism by which IVIG can ameliorate severe invasive group A streptococcal infections.

A remarkable change in the epidemiology of infections due to group A streptococci (GAS) has been noted since the early 1980s (7, 8, 12, 17, 39). Several countries, including the United States and Canada, have reported a remarkable increase in the number of invasive infections due to GAS including a high incidence of streptococcal toxic shock syndrome (STSS) and necrotizing fasciitis cases (reviewed in reference 25). The reason for this increased virulence of GAS remains unknown; however, these bacteria are known to produce a number of virulence factors that can potentially contribute to their invasiveness and trigger the systemic inflammatory response that accompanies many of the severe invasive infections (reviewed in reference 22).

Streptococcal superantigens are believed to make important contributions to the pathogenesis of invasive infections (22, 37). In addition, the surface M protein of the bacteria is considered one of the major virulence factors of these organisms because it protects the bacteria from phagocytic cells (3, 9, 11). Type-specific protective antibodies directed to the M protein opsonize the bacteria and enhance their elimination by phagocytic cells (2, 24). Several studies have suggested that low levels of circulating antibodies to the M protein and/or to streptococcal superantigens may render the host susceptible to invasive infections and possibly contribute to the severity of the clinical manifestations (4, 9, 16, 39).

Despite the use of appropriate antibiotic therapy, early mortality in STSS patients may exceed 50% (7, 25). These observations suggested a need for adjunctive therapy aimed at ameliorating the potent systemic inflammatory response that often accompanies these infections. Pooled normal intravenous polyspecific immunoglobulins G (IVIG) was reasoned to be an ideal adjunctive drug candidate inasmuch as we and others have shown that it contains high levels of antibodies to streptococcal superantigens (32–34, 38). A number of case reports and observational cohort studies have suggested a substantial reduction in mortality when adjunctive IVIG was used in the treatment of STSS patients (1, 20, 30, 38a).

Previous studies from our laboratory have shown that IVIG contains neutralizing antibodies against a broad variety of streptococcal superantigens and that this neutralizing activity is transferable to the plasma of patients who received this drug (34). However, we found that different IVIG preparations vary in the levels of these neutralizing antibodies (32). The aim of the present study is to investigate whether IVIG preparations contain type-specific anti-M-protein antibodies and whether these antibodies can enhance the opsonization of the bacteria. Inasmuch as strains of the M1T1 serotype are the most prevalent among the invasive GAS strains isolated from infected patients through our active surveillance (reviewed in reference 25), our studies have focused on anti-M1 antibodies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Three preparations of IVIG, including Gamimune N, prepared from a Canadian blood pool by Cutter Biologicals (Toronto, Canada), Gammagard S/D, prepared from an European blood pool by Baxter S.A. (Lessines, Belgium), and Venoglobulin-S, prepared from an American blood pool by Alpha Therapeutic Co. (Los Angeles, Calif.), were analyzed in the study. The IVIG in all three preparations was isolated from pooled human plasma by the Cohn-Onkley cold-alcohol fractionation method (18) and contained 94 to 99% immunoglobulin G (IgG), with only trace amounts of IgA and IgM, as specified by the manufacturers. M1T1 strains were isolated from patients with invasive infection due to GAS (i.e., the bacteria were recovered from a normally sterile site) recruited between December 1994 and June 1996. These M1T1 isolates appeared to be derived from the same strain inasmuch as they had an identical Spe genotype and DNA-banding pattern after digestion with two enzymes. A representative M1T1 isolate from an Ontario STSS patient was used in this study.

Cases of invasive GAS infection were classified according to the scheme proposed by the Working Group on Streptococcal Infections (44), and the STSS cases were identified by active surveillance in Ontario, Canada, from 1994 to 1996 (25). Plasma was collected from seven STSS patients before (pre-IVIG plasma) and immediately after (post-IVIG plasma) IVIG infusion. Patients included in this study were infected with a single M1T1 clone (with the same Spe genotype and identical DNA banding pattern in pulsed-field gel electrophoresis after digestion with two enzymes, SmaI and SfiI) and received Gamimune N in doses ranging from 0.4 to 1.0 g/kg.

The presence of anti-M1-protein antibodies in IVIG preparations or in plasma of patients before and after IVIG administration was determined by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) with a peptide copying the N terminus of type M1 protein [SM1(1–26)C], provided by J. B. Dale, as the ELISA antigen. The sequence was deduced from the emm 1.0 allele described by Haanes-Fritz et al. (13). Microtiter plates were coated with 1 μg of the SM1 peptide per ml in coating buffer (0.1 M carbonate buffer [pH 9.6 to 9.8]) at 4°C for 18 h, rinsed with wash buffer (0.05% Tween 20 in phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]), and blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin in PBS for 60 min at 37°C. Fetal bovine serum, diluted 1:100 in PBS, was used as a negative control, and a rabbit anti-M1 antiserum, generated as previously described (23), was diluted 1:1,000 in PBS and used as a positive control. Different dilutions of the various IVIG preparations were added to duplicate coated wells and incubated for 1 to 3 h at room temperature. The plates were rinsed with wash buffer, and goat anti-human or goat-anti rabbit Ig-peroxidase conjugate diluted 1:1,000 was added to the appropriate wells. After 1 to 2 h of incubation, the plates were rinsed with wash buffer and freshly made peroxidase substrate solution (ABST; Kirkegaard-Perry, Gaithersburg, Md.) was added. The reaction was monitored at 415 nm, and the results are expressed as the mean percentage of the positive control ± the standard error (SE).

To detect functional anti-M1 antibodies in IVIG or in patient plasma, a neutrophil-mediated opsonophagocytosis assay was performed by the method of Fischer et al. (10). Neutrophils were isolated from adult venous blood by dextran sedimentation and Ficoll-Hypaque density centrifugation. Bacteria were grown overnight to log phase in Todd-Hewitt broth containing 20% normal rabbit serum; then 50 μl was diluted to 5 ml with Todd-Hewitt broth and allowed to grow at 37°C with occasional monitoring until the optical density of 530 nm reached 0.05 to 0.08. Briefly, 10 μl of this bacterial suspension was incubated with 40 μl of different dilutions of IVIG or with 1:10 and 1:500 dilutions of the rabbit anti-SM1(1–26)C antibody in 96-well round-bottom microtiter plates for 15 min at 37°C followed by incubation on ice for 15 min. Neutrophils (2 × 105 per 40 μl of RPMI 1640 medium) were added to all wells followed by 10 μl of newborn rabbit complement (Rockland Laboratories, Gilberstville, Pa.) and incubated at 37°C for 1 h with end-over-end rotation. The percentage of neutrophils associated with streptococci (percent phagocytosis) was estimated by microscopic counts of Wright-stained (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) smears prepared from the assay mixture. Each assay was performed in triplicate, with 300 to 400 neutrophils counted per slide.

To verify the specificity of the opsonic anti-M1 antibodies, we performed adsorption studies. Bacteria from overnight culture of the M1T1 strain were heat killed at 95°C for 5 min and centrifuged at 800 × g for 5 min. IVIG was adsorbed twice with 1 ml of cell pellet, each time for 1 h at 4°C with constant rotation. After the final incubation, the mixture was centrifuged at 1,500 × g and the supernatant containing the adsorbed IVIG was aspirated. The neutrophil-mediated opsonophagocytosis assay was carried out with unadsorbed and adsorbed IVIG with the M1T1 strain and with an M3T3 strain as a control.

RESULTS

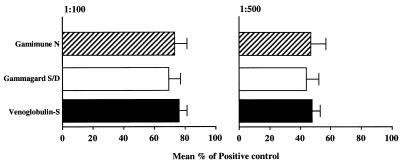

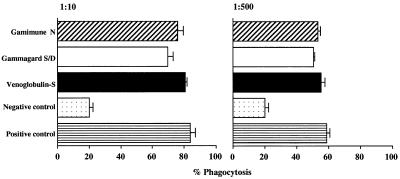

The presence of antibodies to type M1 protein in IVIG preparations was detected by ELISA. All three IVIG preparations contained high levels of anti-M1 antibodies, and there was no significant difference in the levels between the different IVIG preparations tested (Fig. 1). To investigate whether the anti-M1 antibodies were functional, we tested their ability to enhance the phagocytosis of type M1 strains of S. pyogenes. As shown in Fig. 2, all three IVIG preparations increased the phagocytosis of the M1 strain three- to fourfold over background levels, with 80 and 60% phagocytosis at 1:10 and 1:500 dilutions, respectively. This level of anti-M1 opsonic antibodies was identical for all three IVIG preparations as well as for the rabbit anti-M1 antibody control (Fig. 2). In addition, analysis of four different lots of Gamimune IVIG revealed no difference in the levels of anti-M1 opsonic antibodies (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Anti-M1 antibodies in IVIG. Three IVIG preparations were diluted 1:100 or 1:500 in PBS and added to duplicate wells coated with 1 μg of M1 peptide [SM1(1–26)] per ml. Rabbit antiserum specific for the M1 peptide (diluted 1:100 or 1:500) was used as a positive control, and fetal bovine serum (diluted 1:100) was used as a negative control. Peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-human IgG and goat anti-rabbit IgG were used as a secondary antibodies. After the addition of peroxidase substrate, the reaction was monitored at 415 nm. The data was calculated as the percentage of the positive control (rabbit anti-M1 antibody), and the results are the mean ± SE for three separate experiments. No significant difference among the three IVIG preparations was found when the data was analyzed by analysis of variance (P > 0.6). The absorbance of the blank and the positive control at 415 nm was 0.105 and 1.30, respectively.

FIG. 2.

Type M1 opsonic antibodies in IVIG. Neutrophil-mediated opsonophagocytosis of an M1T1 strain of S. pyogenes was evaluated in the presence and absence of diluted IVIG preparation or rabbit anti-M1 antibodies. Rabbit antiserum specific for M1 protein (diluted 1:10 and 1:500) was used as the positive control, and fetal bovine serum was used as the negative control. The assay was conducted as described in Materials and Methods, and the percentage of neutrophils associated with bacteria (percent phagocytosis) was determined by direct light microscopy. The experiment was conducted in triplicates, and the data are presented as the mean ± SE. No significant difference among the three IVIG preparations was found when the data was analyzed by analysis of variance (P = 0.1 and 0.2) at 1:10 and 1:500 dilutions, respectively. Experiments were also performed with different lots of Gamaimune IVIG.

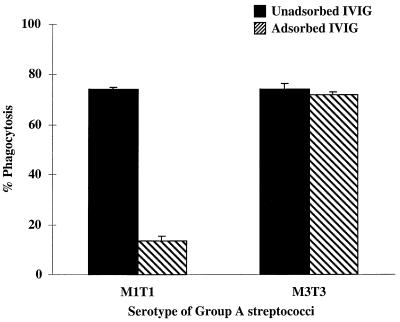

To determine the specificity of the anti-M1 opsonic antibodies, the IVIG was adsorbed with heat-killed M1T1 bacteria and then tested for opsonophagocytic activity against an M1T1 or an M3T3 strain of S. pyogenes. As shown in Fig. 3, the anti-M1 opsonic activity was drastically reduced from 74 to 13.3% after adsorption with M1T1 bacteria whereas the anti-M3 opsonic activity was unchanged.

FIG. 3.

Adsorption of anti-M1 osponic activity with M1T1 bacteria. The specificity of the anti-M1 antibodies in IVIG was determined by comparing the opsonic activity of the unadsorbed IVIG and adsorbed IVIG against an M1T1 or M3T3 strain. The M1 opsonic activity was determined in all three IVIG preparations at 1:10 and 1:500 dilutions. Shown here are the results with Gamaimune IVIG at a 1:500 dilution. Identical results were obtained with the Gammagard and the Venoglobulin-S IVIG preparations at both dilutions.

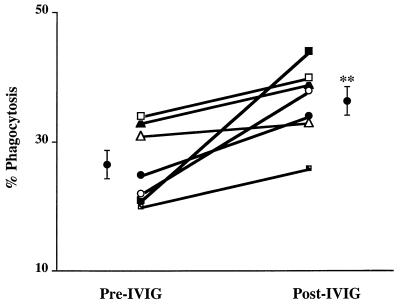

To examine whether the anti-M1 opsonic activity of the IVIG preparation was conferred to the IVIG-treated patients, plasma taken from patients before and immediately after infusion with Gamimune IVIG was tested for the ability to enhance the phagocytosis of the M1T1 strain that was responsible for disease in all patients studied. In six of seven patients who received IVIG, the anti-M1 opsonic activity in the plasma increased following a single dose of IVIG (Fig. 4). There was a significant difference in the level of anti-M1 opsonic activity before and after IVIG infusion, with a mean phagocytosis in pre- and post-IVIG plasma of 27% ± 2% and 36% ± 2%, respectively (P < 0.006).

FIG. 4.

M1-specific opsonic activity is increased in the plasma of STSS patients following IVIG administration. Neutrophil-mediated opsonophagocytic activity was determined in plasma from seven patients before and after IVIG administration. The plasma was diluted 1:10 in PBS and used in the assay as described in the legend to Fig. 2. The experiment was repeated three times, and the mean percent phagocytosis values for the pre-IVIG and post-IVIG samples were compared by the paired Student t test (P < 0.0062).

DISCUSSION

The clinical efficacy of IVIG has been shown in a variety of diseases associated with either viral or microbial infections (1, 14, 20, 21, 31, 36). Recent studies have suggested that IVIG may be effective in the treatment of staphylococcal toxic shock syndrome as well as STSS (1, 20, 36, 41). It is widely believed that the presence of antibodies to the superantigens produced by these bacteria can block the ability of these toxins to activate immune cells and reduce their capacity to elicit potent inflammatory cytokine responses commonly associated with these diseases (28, 30, 35, 40, 42). Indeed, several studies have documented the presence of antibodies to a wide variety of superantigens in IVIG preparations (32–34, 38, 41). Specifically, we have reported that these antibodies neutralize the immunological activity of superantigens produced by group A streptococcal isolates and that this effect is conferred to the plasma of patients who received IVIG (32–34).

We demonstrated here that IVIG preparations also contain opsonic activity against M1T1 GAS. The M1T1 serotype is the most commonly isolated serotype from patients with invasive infections due to GAS (6, 7, 16, 25, 29). Like most M proteins, the M1 protein protects the bacteria against phagocytosis (2, 11); however, these organisms are readily phagocytosed in the presence of type-specific antibodies (23). Several studies have correlated low levels of anti-M1 antibodies with increased risk for invasive infections due to GAS (16, 39). The presence of M-specific opsonic activity in IVIG may help reduce the bacterial load in patients with invasive infections due to GAS.

Reduction of the bacterial load by enhancement of the opsonophagocytosis of the bacteria may not occur quickly enough to halt the systemic manifestations of STSS, which appear to be mediated by superantigen-induced inflammatory cytokines overproduction. Superantigens can exert their potent immune system stimulatory effects at very low concentrations (within the nanogram range), and their activity plateaus within a wide concentration range (26). This may explain why, in may cases, there was no correlation between the magnitude of tissue involvement and disease severity (27). However, in addition to superantigens, other streptococcal virulence factors, particularly streptococcal proteases, contribute importantly to the disease. SpeB, a major streptococcal protease, may contribute directly and indirectly to the systemic manifestation in STSS by activating proinflammatory cytokines, hypotensive agents, and vasodilators (5, 15, 19). Previous studies have shown that IVIG contains high levels of antibodies directed against SpeB (33, 34). Therefore, neutralizing antibodies against streptococcal superantigens and proteases in IVIG may have an immediate effect on halting the systemic manifestations of STSS, while the opsonic antibodies may have a long-term benefit by helping to eliminate bacteria from tissues. Together, these activities of IVIG may help ameliorate disease.

Previous studies by Fischer and colleagues have demonstrated the presence of opsonic antibodies against group B streptococci in IVIG preparations (10, 43) and other neonatal pathogens, including Staphylococcus epidermidis, Haemophilus influenzae type b, and several serotypes of Streptococcus pneumoniae. They found that pathogen-specific opsonic activity varied for different IVIG preparations and was dependent on the donor pool (43). Although we have found similar variations in the level of superantigen-specific neutralizing antibodies among different IVIG preparations and even among different lots of the same preparations, in this study we found no significant difference in the level of M1-specific opsonic antibodies among the three preparations tested or among different lots of the same preparation. Further studies are needed to explore whether this finding will hold for other commercial preparations of IVIG obtained from different parts of the world.

Another notable difference between superantigen-specific and M1-specific opsonic antibodies in IVIG preparations is in the relation between the binding and functional activity of these antibodies. Previously, we found no correlation between the presence of antibodies that can bind a specific superantigen and the ability of these antibodies to neutralize the immunological activity of the superantigen (33). By contrast, we found in this study a good correlation between the level of anti-M1 antibodies, as detected by ELISA, and the M1-specific opsonic activity in IVIG (R = 0.8, P < 0.05).

In summary, we have demonstrated that in addition to the superantigen-neutralizing activity of IVIG, high levels of opsonic activity against one of the most prevalent serotypes of GAS, the M1T1 serotype, are present in these pooled preparations. We have also shown that this activity, like the superantigen-neutralizing activity, is conferred to patients receiving IVIG therapy. Together, these activities may contribute to the ability of IVIG, when used as an adjunctive therapy in STSS, to reduce the morbidity and mortality rates in patients (20).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the U.S. Veterans Administration (to M.K.), the National Institutes of Health (grant NIAID AI40198 to M.K.), DOD/VA Emerging Pathogens (to M.K.), the Swedish Society of Medical Research (to A.N.-T.), and the U.S.-Egypt Channel Scholarships Fund (to H.B.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Barry W, Hudgins L, Donta S T, Pesanti E L. Intravenous immunoglobulin therapy for toxic shock syndrome. JAMA. 1992;267:3315–3316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beachey E H, Bronze M, Dale J B, Kraus W, Poirier T, Sargent S. Protective and autoimmune epitopes of streptococcal M proteins. Vaccine. 1988;6:192–196. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(88)80027-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beachey E H, Seyer J M. Primary structure and immunochemistry of group A streptococcal M proteins. Semin Infect Dis. 1982;4:401–410. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bisno A L, Stevens D L. Streptococcal infections of skin and soft tissues. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:240–245. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199601253340407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burns E H, Jr, Marciel A M, Musser J M. Activation of 66-kilodalton human endothelial cell matrix metalloprotease by Streptococcus pyogenes extracellular cysteine protease. Infect Immun. 1996;64:4744–4750. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.11.4744-4750.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cleary P P, Kaplan E L, Handley J P, Wlazlo A, Kim M H, Hauser A R, Schlievert P M. Clonal basis for resurgence of serious Streptococcus pyogenes disease in the 1980s. Lancet. 1992;339:518–521. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)90339-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davies H D, McGeer A, Schwartz B, Green K, Cann D, Simor A E, Low D E Ontario Streptococcal Study Group. Invasive group A streptococcal infections in Ontario, Canada. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:547–554. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199608223350803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Demers B, Simor A-E, Vellend H, Schlievert P M, Byrne S, Jamieson F, Valmsley S, Low D E. Severe invasive group A streptococcal infections in Ontario, Canada: 1987–1991. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;16:792–800. doi: 10.1093/clind/16.6.792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferrieri P. Microbiological features of current virulent strains of group A streptococci. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1991;10:S20–S24. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199110001-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fischer G W, Wilson S R, Hunter K W. Functional characteristics of a modified immunoglobulin preparation for intravenous administration: summary of studies of opsonic and protective activity against group B streptococci. J Clin Immunol. 1982;2:31–35S. doi: 10.1007/BF00918364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fischetti V A. Streptococcal M protein. Sci Am. 1991;264:58–65. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0691-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gaworzewska E, Colman G. Changes in the pattern of infection caused by Streptococcus pyogenes. Epidemiol Infect. 1988;100:257–269. doi: 10.1017/s095026880006739x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haanes-Fritz E, Kraus W, Burdett V, Dale J B, Beachey E H, Cleary P P. Comparison of the leader sequences of 4 group A streptococcal M protein genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;10:4667–4677. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.10.4667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hall P D. Immunomodulation with intravenous immunoglobulin. Pharmacotherapy. 1993;13:564–573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herwald, H., M. Collin, W. Muller-Esterl, and L. Bjorck. 1996. Streptococcal cysteine proteinase releases kinins: a virulence mechanism. J. Exp. Med. 665–673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Holm S E, Norrby A, Bergholm A M, Norgren M. Aspects of pathogenesis of serious group A streptococcal infections in Sweden, 1988–1989. J Infect Dis. 1992;166:31–37. doi: 10.1093/infdis/166.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Isphani P, Donald F E, Aveline A J D. Streptococcus pyogenes bacteremia: an old enemy subdued, but not defeated. J Infect. 1988;16:37–46. doi: 10.1016/s0163-4453(88)96073-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Janeway C A, Emnders J F, Oncley J L. Use of fraction II-3 in the preparation of serum gammaglobulin (human). 1946. Memorandum to Division of Medical Sciences, National Research Council. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kapur V, Majesky M W, Li L-L, Black R A, Musser J M. Cleavage of interleukin 1β (IL-1β) precursor to produce active IL1-β by a conserved extracellular cysteine protease from Streptococcus pyogenes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:7676–7680. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.16.7676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaul R, McGeer A, Norrby-Teglund A, Kotb M, Low D E. Program and Abstracts of the 35th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1995. Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) therapy in streptococcal toxic shock syndrome (STSS): results of a matched case-control study, abstr. LM68. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaveri, S. V., L. Mouthon, and M. D. Kazatchkine. 1994. Immunomodulating effects of intravenous immunoglobulin in autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 57(Suppl.):6–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Kotb M. Bacterial pyrogenic exotoxins as superantigens. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1995;8:411–426. doi: 10.1128/cmr.8.3.411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kraus W, Dale J B, Beachey E H. Identification of an epitope of type 1 streptococcal M protein that is shared with a 43-kD protein of human myocardium and renal glomeruli. J Immunol. 1990;145:4089–4093. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lancefield R L. Current knowledge of the type-specific M antigens of group A streptococci. J Immunol. 1962;89:307–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Low, D. E., B. Schwartz, and A. McGeer. The reemergence of severe group A streptococcal disease: an evolutionary perspective. In Emerging pathogens. Proceedings of the 1996 International Congress on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, in press.

- 26.Marrack P, Kappler J. The staphylococcal enterotoxins and their relatives. Science. 1990;248:705–711. doi: 10.1126/science.2185544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McGeer, A., et al. Unpublished data.

- 28.Miethke T, Wahl C, Regele D, Gaus H, Heeg K, Wagner H. Superantigen mediated shock: a cytokine release syndrome. Immunobiology. 1993;189:270–284. doi: 10.1016/S0171-2985(11)80362-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Musser J M, Kapur V, Szeto J, Pan X, Swanson D S, Martin D R. Genetic diversity and relationship among Streptococcus pyogenes strains expressing serotype M1 protein: recent intercontinental spread of a subclone causing episodes of invasive disease. Infect Immun. 1995;63:994–1003. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.3.994-1003.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nadal D, Lauener R P, Braegger C P, Kaufhold A, Simma B, Lutticken R, Seger R A. T cell activation and cytokine release in streptococcal toxic shock-like syndrome. J Pediatr. 1993;122:727–729. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(06)80014-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Newburger J W, Takahashi M, Burns J C, Beiser A S, Chung K J, Duffy C E, Glode M P, Mason W H, Reddy V, Sanders S P, Shulman S T, Wiggins J W, Hicks R V, Fulton D R, Lewis A B, Leung D Y M, Colton T, Rosen F S, Melish M E. The treatment of Kawasaki syndrome with intravenous gamma globulin. N Engl J Med. 1986;315:341–347. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198608073150601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Norrby-Teglund A, Basma H, Andersson J, McGeer A, Low D E, Kotb M. Varying titers of neutralizing antibodies to streptococcal superantigens in different preparations of normal polyspecific immunoglobulin G (IVIG): implications for therapeutic efficacy. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:631–638. doi: 10.1086/514588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Norrby-Teglund A, Kaul R, Low D E, McGeer A, Andersson J, Andersson U, Kotb M. Evidence for the presence of streptococcal superantigen-neutralizing antibodies in normal polyspecific immunoglobulin G. Infect Immun. 1996;64:5395–5398. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.12.5395-5398.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Norrby-Teglund A, Kaul R, Low D E, McGeer A, Newton D W, Andersson J, Andersson U, Kotb M. Plasma from patients with severe invasive group A streptococcal infections treated with normal polyspecific IgG inhibits streptococcal superantigen-induced T cell proliferation and cytokine production. J Immunol. 1996;156:3057–3064. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Norrby-Teglund A, Norgren M, Holm S E, Andersson U, Andersson J. Similar cytokine induction profiles of a novel streptococcal exotoxin, MF, and pyrogenic exotoxins A and B. Infect Immun. 1994;62:3731–3738. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.9.3731-3738.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ogawa M, Ueda S, Anzai N, Ito K, Ohto M. Toxic shock syndrome after staphylococcal pneumonia treated with intravenous immunoglobulin. Vox Sang. 1995;68:59–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.1995.tb02548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schlievert P M. Role of superantigens in human diseases. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:997–1002. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.5.997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Skansen-Saphir U, Andersson J, Bjork L, Andersson U. Lymphokine production induced by streptococcal pyrogenic exotoxin-A is selectively down-regulated by pooled human IgG. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:916–922. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830240420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38a.Stegmayer B, Björck S, Holm S, Nisell J, Rydvall A, Settergren B. Septic shock induced by group A streptococcal infection: clinical and therapeutic aspects. Scand J Infect Dis. 1992;24:589–597. doi: 10.3109/00365549209054644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stevens D L. Invasive group A streptococcus infections. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;14:2–13. doi: 10.1093/clinids/14.1.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sullivan G W, Mandell G L. The role of cytokines in infection. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 1991;4:344–349. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Takei S, Arora Y K, Walker S M. Intravenous immunoglobulin contains specific antibodies inhibitory to activations of T cells by staphylococcal toxin superantigens. J Clin Invest. 1993;91:602–607. doi: 10.1172/JCI116240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Walley K R, Lukacs N W, Standiford T J, Strieter R M, Kunkel S L. Balance of inflammatory cytokines related to severity and mortality of murine sepsis. Infect Immun. 1996;64:4733–4738. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.11.4733-4738.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weisman L E, Cruess D F, Fischer G W. Opsonic activity of commercially available standard intravenous immunoglobulin preparations. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1994;13:1122–1125. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199412000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Working Group on Severe Streptococcal Infections. Defining the group A streptococcal toxic shock syndrome. Rationale and consensus definition. JAMA. 1993;269:390–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]