Abstract

The results of this study to dissect the nature of the acquired immune response to infection with Listeria monocytogenes in mice with targetted gene disruptions show that successful resolution of disease requires the essential presence of αβ T cells and the capacity to elaborate gamma interferon. In the absence of either of these entities, mice experience increasingly severe hepatitis and tissue necrosis and die within a few days. The data from this study support the hypothesis that the protective process is the efficient replacement of neutrophils in lesions by longer-lived mononuclear phagocytes; αβ-T-cell-knockout mice died from progressive infection before neutrophil replacement could occur, whereas in γδ-T-cell-knockout mice this replacement process in the liver has previously been shown to be much slower. In the present study we attribute this delay to reduced production of the macrophage-attracting chemokine MCP-1 in the γδ-T-cell-knockout animals. These data further support the hypothesis that γδ T cells are important in controlling the inflammatory process rather than being essential to the expression of protection.

Listeria monocytogenes is an intracellular bacterial parasite that, in addition to infecting host macrophages, can colonize liver hepatocytes and other parenchymal cells. As a result, the infected host faces both the problem of dealing with a very rapidly growing pathogen and the problem of sterilizing the infected tissues.

There is a general consensus that the very early innate response to infection is mediated by neutrophils (13–16, 47) although at this time NK cells may also play a role (2–5). In the liver, bacilli are released from parenchymal cells and hepatocytes by lysis by neutrophils and macrophages, with the latter cells becoming activated to a bactericidal state by gamma interferon (IFN-γ) production.

These events are followed by the rapid generation (within 2 to 3 days) of acquired immunity (44). Although several early reports pointed to a role by class II-restricted Lyt.2− T cells (30, 32–37, 51), evidence slowly accumulated in favor of the concept that CD8 (Lyt.2+) T cells in fact played the primary role in resolution of the infection (1, 7, 11, 12, 18, 19, 27, 38, 40, 41, 46). Subsequently, more recent reports have demonstrated that other αβ-T-cell-negative populations (NK and γδ T cells) could also contribute to some extent to resistance to the infection, presumably reflecting their ability to secrete IFN-γ (2–6, 8, 23, 26, 39, 50). Whereas some have argued that this represents a form of compensatory immunity (46), others have proposed that interactions between γδ T cells and NK cells comprise a complex regulatory network, preceding and perhaps influencing or controlling the proliferation of T cells mediating the αβ-T-cell response (31, 39, 42).

We have approached this question in a new manner by comparing the course of listeriosis in mice with gene disruptions (KO). The results of the study show that IFN-secreting αβ T cells are essential to disease resolution, a process that relies on the efficient replacement of an early neutrophil response that if allowed to proceed resulted in increasingly severe hepatitis and tissue necrosis, with a mononuclear phagocyte influx that mediated sterilization and prevented further tissue damage. T cells bearing γδ receptors appear to contribute to this mechanism by production (or induction) of the macrophage chemokine MCP-1, which enhances this replacement process.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental infections.

Homozygous female mice with targetted gene disruption of the β chain of the T-cell receptor (αβ KO), the δ chain (γδ KO), or the gene encoding IFN-γ as well as control C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, Maine) and used when 8 weeks of age. They were infected intravenously via a lateral tail vein with 2 × 103 L. monocytogenes EGD organisms. The course of the infection was monitored against time by plating serial dilutions of individual whole-organ homogenates on tryptic soy agar and counting bacterial colony formation after 24 h of incubation at 37°C in humidified air.

Histology.

Tissues were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde, routinely sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Sections were read by an experienced veterinary pathologist without prior knowledge of treatment groups.

Reverse transcription-PCR for cytokine expression in vivo.

Infected tissues were excised, placed in Ultraspec (Cinna/Biotecx, Friendswood, Tex.), and homogenized, and RNA was extracted as described previously (17). One microgram of total RNA was reverse transcribed, diluted, and subjected to PCR expansion of cytokine-specific cDNA. The amount of cytokine-related product was determined by the exposure of blotted cDNA PCR product to a fluorescein-tagged target protein sequence-specific probe. The fluorescein was detected by using the enhanced chemiluminescence kit (ECL; Amersham, Arlington Heights, Ill.), which produces a light signal that can be detected on film. The number of cycles which generate a log-linear relationship between the signal on film and the dilution of the sample was determined empirically, and data were expressed as the mean pixel value for four samples from four separate mice.

RESULTS

Course of Listeria infection in gene-disrupted mice.

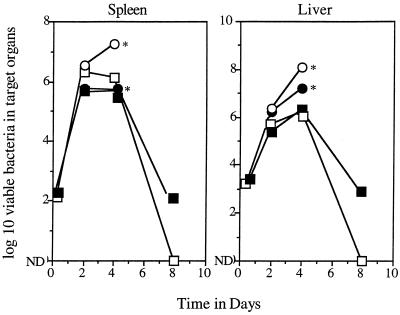

After intravenous infection, L. monocytogenes grew progressively in the spleens and livers of control animals for 2 to 4 days, after which time the infection was rapidly cleared, with no remaining bacteria detected on day 8 (the results of a representative experiment are shown in Fig. 1). In γδ-KO mice, no differences were seen in the bacterial load up to day 4, but after this time the infection resolved more slowly compared to that in controls (this was particularly evident in the liver; in one experiment it took 23 days before this organ was devoid of detectable viable bacteria).

FIG. 1.

Course of L. monocytogenes infection in control and KO mice. Data are expressed as mean values (n = 4); standard errors of the means did not exceed 0.35. ND, no bacterial colonies detected; ∗, no survivors after day 4. ○, IFN-KO mice; ▪, γδ-KO mice; •, αβ-KO mice; □, controls.

Mice lacking the ability to produce IFN showed no evidence of control of the infection, and there were no survivors after day 4. A similar event occurred in αβ-KO mice, despite some evidence of slowing of the infection in the spleens of these animals.

Histologic appearance of liver tissues.

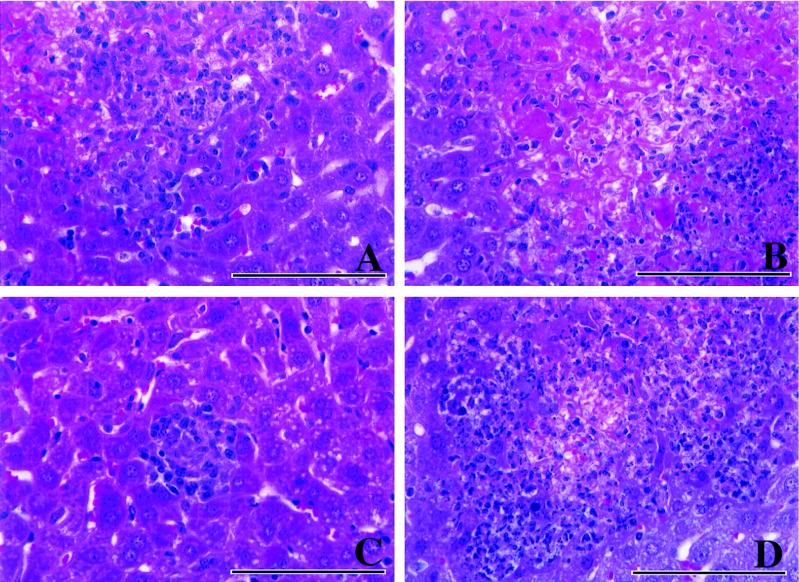

The histologic data obtained for liver samples are summarized in Table 1. In control mice, mild hepatitis seen over the first 2 days increased in severity by day 4, with lesions containing mixtures of macrophages and smaller numbers of neutrophils (Fig. 2). On day 8 small foci of necrosis were still observed, but otherwise the inflammation was decreased. Some neutrophils could still be found, but the infiltrate consisted predominantly of macrophages.

TABLE 1.

Histologic appearance of liver tissues

| Mouse group | Results on day postinfection indicated

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | |

| Controls | No lesions | Mild hepatitis, mononuclear cells without necrosis | Moderate hepatitis, with macrophages and fewer neutrophils | Moderate hepatitis, with small foci of necrosis present |

| αβ KO | No lesions | No lesions | Moderate necrotizing hepatitis with neutrophils | —a |

| γδ KO | No lesions | Mild hepatitis, with small foci of necrosis | Mild hepatitis, predominantly mixed macrophages and lymphocytes | Moderate hepatitis, with small foci of necrosis |

| IFN KO | No lesions | Hepatic necrosis without inflammation | Moderate hepatitis, with increased neutrophils and necrosis | — |

—, no survivors.

FIG. 2.

Hematoxylin-and-eosin staining of liver sections from infected mice 4 days after inoculation with an immunizing dose of L. monocytogenes. (A) Control mouse. Macrophages predominate, with lymphocytes and scattered neutrophils also present. (B) αβ-KO mouse. A large area of severe hepatic necrosis is evident, with a rim of degenerate neutrophils present (right side). (C) γδ-KO mouse. A small focus of infection can be seen in this section, which contains lymphocytes and macrophages. (D) IFN-KO mouse. An area of necrosis is surrounded by a large number of inflammatory cells, most of which are neutrophils. Bars, 100 μm.

The early cellular response in αβ-KO mice was similar to that in controls, but these animals showed signs of increasingly severe necrotizing hepatitis and died after day 4. In these animals neutrophil infiltration was substantially increased compared with that in controls. A similar pattern was seen in IFN-KO mice, with an increased neutrophil infiltration and increasingly severe necrosis.

In γδ-KO mice the pattern was very similar to that in controls, with mild hepatitis and only scattered small foci of necrosis, but with fewer macrophages evident on day 4 (Fig. 2). The only major difference between these mice and control animals was a more-mixed inflammation, consisting of both macrophages and neutrophils, in the liver on and after day 8, as previously observed (26).

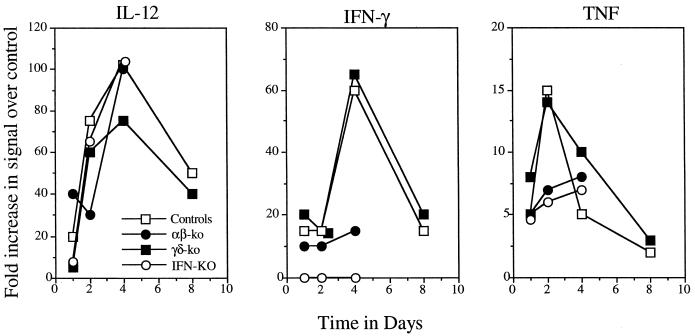

Cytokine or chemokine message expression in livers of infected mice.

All four groups of mice produced equivalent amounts of interleukin 12 (IL-12) in infected tissues (data for the liver are shown in Fig. 3) and, with the exception of the IFN-KO mice, all produced IFN as would be expected. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) message was seen in controls and γδ-KO mice for the first 2 days, but much lower levels were seen in αβ-KO and IFN-KO mice.

FIG. 3.

Generation of mRNA message encoding key cytokines in the livers of infected mice (n = 4).

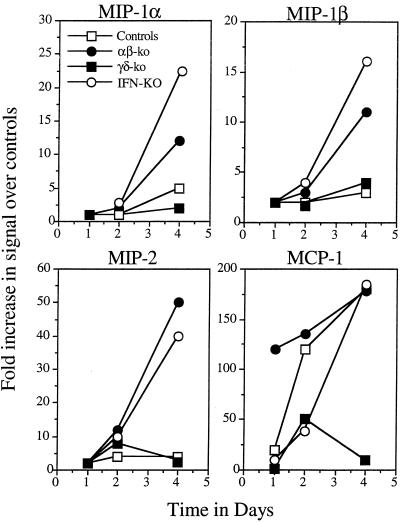

Given the histology results, which indicated a higher neutrophilic response in the αβ-KO and IFN-KO mice leading to hepatitic necrosis and death of these animals, we examined the early chemokine response in each group. The generation of macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP) signals in the αβ-KO and IFN-KO mice was substantially elevated compared to that in γδ-KO and control mice for the first 4 days, consistent with the sustained neutrophilia (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Generation of mRNA message encoding neutrophil attractant chemokines (MIP family) and the macrophage attractant chemokine MCP-1 in the livers of infected mice (n = 4) (P < 0.005; αβ-KO mice versus γδ-KO mice).

Perhaps the most interesting finding, however, was data relating to production of the macrophage chemoattractant chemokine MCP-1. Production of this chemokine was very high in αβ-KO mice and increased substantially in controls and IFN-KO mice. On the other hand, only very low levels of message were observed in the γδ-KO mice (P < 0.005; αβ-KO mice versus γδ-KO mice).

DISCUSSION

The results of this study show that mice that are capable of recruiting blood-borne monocytes into sites of infectious inflammation in a timely manner so as to clear and replace shorter-lived polymorphonuclear phagocytes are thus able to curtail the overwise increasing hepatic necrosis and survive an acute L. monocytogenes infection. In animals unable to express this mechanism, an acute necrotic hepatitis proceeds unabated and kills the animal in a few days.

The use of mice with gene disruptions in this study clearly showed that αβ T cells, but not γδ T cells, were essential to this process, as was the ability to secrete the cytokine IFN-γ. In mice lacking αβ T cells, necrosis in the liver increased progressively, with the animals dying within 4 to 5 days. An identical pattern was seen for IFN-KO mice, thus illustrating that this molecule is essential to the correct expression of antimicrobial immunity. In contrast, in mice lacking γδ T cells, bacterial clearance was a little slower in the spleens and livers, with pyogranulomatous lesions occurring in the latter organ taking longer to resolve, as previously noted by other laboratories (26, 42). These data therefore indicate that γδ T cells play an important role in the inflammatory process in listeriosis but are not essential to animal survival.

The results are consistent with the following hypothesis. The rapidly growing infection generates local tissue damage and results in prostaglandin and vasoactive amine production, triggering a rapid influx of neutrophils. These cells play a protective role (13–16, 47), but they are also short-lived; hence, their accumulation in the liver induces a mild-to-moderate hepatitis causing increasing local necrosis. Lysis of hepatocytes by neutrophils, macrophages, or incoming CD8 T cells will collectively contribute to this necrosis for the first few days of the infection (14–16, 28, 48).

The data are consistent with the hypothesis that the successful eventual resolution of the infection depends upon the replacement of this early inflammatory response by a second wave of inflammatory macrophages which destroy remaining bacilli and prevent dissemination. In mice lacking αβ T cells this event does not occur, and so neutrophil influx and necrosis continue, and the animals die soon after, most likely from acute hepatitis. In animals lacking γδ T cells, bacterial clearance from the liver is slower, more neutrophils are seen in lesions (26), and the infection is resolved more slowly. Based on these findings, it seems that both αβ and γδ T cells in normal animals contribute to control of the inflammatory process.

In normal (αβ-T-cell-positive) mice, macrophages activated by IFN secrete TNF, which can stimulate local tissue cells to produce a wide spectrum of chemokines (45), including the macrophage chemoattractant β chemokine MCP-1. The current results however tend to suggest that γδ T cells are either a primary source or a primary inducer of this material in that γδ-KO mice produced considerably smaller amounts of mRNA encoding this molecule for the first 4 days of the infection. The data clearly show that much less MCP-1 is produced in γδ-KO mice, and therefore it is reasonable to hypothesize that this is the reason why macrophages replace neutrophils in lesions in these mice more slowly. In αβ-KO mice, MCP-1 message was still seen due to the continued presence of γδ T cells, and in fact, the elevated levels of this chemokine seen early compared to that in normal, infected mice may suggest some degree of control of γδ-T-cell MCP-1 production by αβ T cells. In the absence of these latter cells however, the animal clearly cannot control the progressively growing infection and hence dies from acute hepatitis before neutrophil replacement with macrophages can begin to take place. As further evidence for the hypothesis, we have found expression of MCP-1 mRNA message in γδ-T-cell-cloned cell lines (43).

The data also imply that the putative recruitment of monocytes into lesions by MCP-1 takes days to develop. There was only a sparse influx of these cells in αβ-KO mice by day 4, despite the strong MCP-1 message in these mice, at which point the liver necrosis was moderate to severe. Presumably, the continued presence of neutrophils at this time was in response to both the infection and the tissue damage caused by the increasing necrosis.

This model is completely consistent with models for other infectious diseases, such as tuberculosis, in which the lungs of γδ-KO infected mice develop pyogranulomatous lesions containing significant numbers of neutrophils (21), and influenza, in which the influx of γδ T cells occurs in parallel with the inflammatory response (9, 10). In those models, as in this one, there was no hard evidence that γδ T cells are essential to protection. As a result, instead, these data seem collectively to point to a “traffic cop” role for γδ T cells, in which they promote the influx of macrophages and reduce neutrophil influx. The most simple explanation is that this response is directly due to MCP-1 production, which attracts macrophages which in turn physically prevent further neutrophil influx into the site. Other more subtle possibilities are that factors released by γδ T cells influence blood vessel adhesion molecules that reduce neutrophil traffic or somehow dampen local tissue damage that would otherwise attract these neutrophils. In the absence of γδ T cells, other local tissue cells produce MCP-1, but as observed, granulomatous foci are initially smaller and the infection takes longer to fully resolve.

Others, however, have proposed much-more-complicated mechanisms to explain the acquired response to L. monocytogenes. Mombaerts et al. (42) have presented data to indicate that both αβ-KO and γδ-KO mice are fully capable of controlling and resolving L. monocytogenes infections, whereas Ladel et al. (39) have suggested that αβ-KO mice are initially even more resistant to infection than normal control mice, contrary to our own observation of rapidly fatal infection in αβ-KO animals. In addition, the latter study (39) also showed that neutralization of IFN-γ by infusion of monoclonal antibody for the first few days only marginally influenced resolution of disease in both γδ-KO and αβ-KO mice; again, in the present study, the infection was rapidly fatal in IFN-KO mice. Several other investigators (20, 49, 54, 55) have reached conclusions similar to ours.

It has been proposed (31, 39, 42) that successful resolution of listeriosis involves early interactions between γδ T cells and NK cells and that this regulatory function of γδ T cells then extends to the emerging αβ-T-cell population, in an antiproliferative manner. (We have γδ-KO mice in our breeding colony that are over 18 months old and have shown no evidence of lymphoproliferative disease, contrary to the idea that γδ T cells “control” the αβ-T-cell response [31].) In addition, it has been proposed (53) that the αβ-T-cell population is in fact the cause of the necrotic lesions in γδ-KO mice, despite the facts that these lesions eventually resolve in such animals and that such lesions develop in αβ-KO mice. While such mechanisms may exist, the similar numbers of bacteria in both controls and γδ-KO mice in the first few days, as well as an apparently normal cytokine response and a mild inflammatory response, strongly support the hypothesis that such mechanisms are minor and not essential. Furthermore, there is direct photographic evidence that the influx of cells into liver lesions in these first days is one of neutrophils (13); lymphocytes are few and scattered, and large granulocytic lymphocytes (NK like) are rarely seen (25).

In this regard, there is some evidence (2–5, 22, 39), with one exception (52), that the presence of NK cells may be necessary for resistance to listeriosis, specifically as an “innate” source of IFN, as revealed by experiments in which IFN activation of macrophages can occur in the absence of T cells (4). In addition, however, production of this cytokine by NK cells is then believed to stimulate infected macrophages to begin to produce IL-12 (29, 53). It will be clear, however, that the results of the current study are not in keeping with this latter hypothesis, in that mRNA encoding IL-12 increased for the first 4 days of the infection in similar manners in both controls and IFN-KO mice. This finding strongly suggests that IFN is therefore not essential to subsequent IL-12 production.

In addition, NK cells that also express the CD4 molecule and which secrete IL-4 have recently been suggested as the underlying inducers of MCP-1 production very early during L. monocytogenes infection (24). In the current study however, message for MCP-1 increased more slowly, and if driven by an IL-4-secreting NK+ CD4+ population, should have been equally represented in the γδ-KO mice. This was not the case, although the data cannot discount the possibility that NK cells are needed to drive MCP-1 production by γδ T cells. Infection of IL-4-KO mice should help resolve the importance of this mechanism.

That is not to say, however, that results obtained with gene-disrupted mice should not also be interpreted with caution. It is apparent that compensatory mechanisms certainly occur in KO mice, and many of these animals have been derived from backcrosses with other mouse strains that may influence their susceptibility. Finally, the failure of others to observe the mortality seen in certain KO mice in the current study may reflect their use of an inoculum of bacteria that may have been much less virulent than that used here.

Having said that, our data support the hypothesis that it is a response by IFN-γ-secreting αβ T cells that is critical to host survival to listeriosis and that this mechanism, in addition to activation of infected macrophages, has as an essential component the efficient replacement of the early neutrophil response by a mononuclear cell influx, preventing an otherwise fatal progression of tissue damage, continued neutrophil infiltration and degeneration, and hepatic necrosis. The data support the concept that γδ T cells play an important role in this process by producing chemokines that enhance this replacement process.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by NIH grant AI-44808 and a postdoctoral fellowship from the Arthritis Foundation (to A.M.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Baldridge J R, Barry R A, Hinrichs D J. Expression of systemic protection and delayed-type hypersensitivity to Listeria monocytogenes is mediated by different T cell subsets. Infect Immun. 1990;58:654–658. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.3.654-658.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bancroft G J. The role of natural killer cells in innate resistance to infection. Curr Opin Immunol. 1993;5:503–510. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(93)90030-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bancroft G J, Kelly J P. Macrophage activation and innate resistance to infection in SCID mice. Immunobiology. 1994;191:424–431. doi: 10.1016/S0171-2985(11)80448-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bancroft G J, Schreiber R D, Bosma G C, Bosma M J, Unanue E R. A T cell-independent mechanism of macrophage activation by interferon-gamma. J Immunol. 1987;139:1104–1107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bancroft G J, Schreiber R D, Unanue E R. Natural immunity: a T-cell-independent pathway of macrophage activation, defined in the scid mouse. Immunol Rev. 1991;124:5–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1991.tb00613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Belles C, Kuhl A K, Donoghue A J, Sano Y, O’Brien R L, Born W, Bottomly K, Carding S R. Bias in the gamma delta T cell response to Listeria monocytogenes. V delta 6.3+ cells are a major component of the gamma delta T cell response to Listeria monocytogenes. J Immunol. 1996;156:4280–4289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berche P, Deceusefond C, Theodoru I, Stiffel C. Impact of genetically regulated T cell proliferation on acquired resistance to Listeria monocytogenes. J Immunol. 1989;132:932–939. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Born W K, O’Brien R L, Modlin R L. Antigen specificity of gamma delta T lymphocytes. FASEB J. 1991;5:2699–2705. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.5.12.1717333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carding S R. A role for gamma/delta T cells in the primary immune response to influenza virus. Res Immunol. 1990;141:603–606. doi: 10.1016/0923-2494(90)90065-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carding S R, Allan W, Kyes S, Hayday A, Bottomly K, Doherty P C. Late dominance of the inflammatory process in murine influenza by gamma/delta + T cells. J Exp Med. 1990;172:1225–1231. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.4.1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheers C, Sandrin M S. Restriction in adoptive transfer of resistance to Listeria monocytogenes. II. Use of congenic and mutant mice show transfer to be H-2K restricted. Cell Immunol. 1983;7:199–205. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(83)90274-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen-Woan M, McGregor D D. The mediators of acquired resistance to Listeria monocytogenes are contained within a population of cytotoxic T cells. Cell Immunol. 1984;87:538–543. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(84)90022-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Conlan J W. Early pathogenesis of Listeria monocytogenes infection in the mouse spleen. J Med Microbiol. 1996;44:295–302. doi: 10.1099/00222615-44-4-295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Conlan J W, Dunn P L, North R J. Leukocyte-mediated lysis of infected hepatocytes during listeriosis occurs in mice depleted of NK cells or CD4+ CD8+ Thy1.2+ T cells. Infect Immun. 1993;61:2703–2707. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.6.2703-2707.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Conlan J W, North R J. Neutrophil-mediated dissolution of infected host cells as a defense strategy against a facultative intracellular bacterium. J Exp Med. 1991;174:741–744. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.3.741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Conlan J W, North R J. Neutrophils are essential for early anti-Listeria defense in the liver, but not the spleen or peritoneal cavity, as revealed by a granulocyte-depleting monoclonal antibody. J Exp Med. 1994;179:259–268. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.1.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cooper A M, Magram J, Ferrante J, Orme I M. Interleukin 12 (IL-12) is crucial to the development of protective immunity in mice intravenously infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Exp Med. 1997;186:39–45. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.1.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Czuprynski C J, Brown J F. Dual regulation of anti-bacterial resistance and inflammatory neutrophil and macrophage accumulation by L3T4+ and Lyt.2+ Listeria-immune T cells. Immunology. 1987;60:287–293. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Czuprynski C J, Brown J F. Effects of purified anti-Lyt-2 mAb treatment on murine listeriosis: comparative roles of Lyt-2+ and L3T4+ cells in resistance to primary and secondary infection, delayed-type hypersensitivity and adoptive transfer of resistance. Immunology. 1990;71:107–112. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dai W J, Bartens W, Kohler G, Hufnagel M, Kopf M, Brombacher F. F. Impaired macrophage listericidal and cytokine activities are responsible for the rapid death of Listeria monocytogenes-infected IFN-gamma receptor-deficient mice. J Immunol. 1997;158:5297–5304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.D’Souza C D, Cooper A M, Frank A A, Mazzaccaro R J, Bloom B R, Orme I M. An anti-inflammatory role for γδ T lymphocytes in acquired immunity to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Immunol. 1997;158:1217–1221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dunn P L, North R J. Early gamma interferon production by natural killer cells is important in defense against murine listeriosis. Infect Immun. 1991;59:2892–900. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.9.2892-2900.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dunn P L, North R J. Resolution of primary murine listeriosis and acquired resistance to lethal secondary infection can be mediated predominantly by Thy-1+ CD4− CD8− cells. J Infect Dis. 1991;164:869–877. doi: 10.1093/infdis/164.5.869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Flesch I E, Wandersee A, Kaufmann S H E. IL-4 secretion by CD4+ NK1+ T cells induces monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 in early listeriosis. J Immunol. 1997;159:7–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frank, A. A. and I. M. Orme. 1997. Unpublished data.

- 26.Fu Y X, Roark C E, Kelly K, Drevet D, Campbell P, O’Brien R, Born W. Immune protection and control of inflammatory tissue necrosis by gamma delta T cells. J Immunol. 1994;153:3101–3115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harty J T, Bevan M J. CD8+ T cells specific for a single nonamer epitope of Listeria monocytogenes are protective in vivo. J Exp Med. 1992;175:1531–1538. doi: 10.1084/jem.175.6.1531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harty J T, Bevan M J. CD8 T-cell recognition of macrophages and hepatocytes results in immunity to Listeria monocytogenes. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3632–3640. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.9.3632-3640.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaplan M H, Sun Y L, Hoey T, Grusby M J. Impaired IL-12 responses and enhanced development of Th2 cells in Stat4-deficient mice. Nature. 1996;382:174–177. doi: 10.1038/382174a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaufmann S H E. Enumeration of Listeria monocytogenes-reactive L3T4+ T cells activated during infection. Microb Pathog. 1986;1:249–260. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(86)90049-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaufmann S H E, Blum C, Yamamoto S. Crosstalk between alpha/beta T cells and gamma/delta T cells in vivo: activation of alpha/beta T-cell responses after gamma/delta T-cell modulation with the monoclonal antibody GL3. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:9620–9624. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.20.9620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaufmann S H E, Brinkmann V. Attempts to characterize the T-cell population and lymphokine involved in the activation of macrophage oxygen metabolism in murine listeriosis. Cell Immunol. 1984;88:545–550. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(84)90186-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaufmann S H E, Hahn H. Biological functions of T cell lines with specificity for the intracellular bacterium Listeria monocytogenes in vitro and in vivo. J Exp Med. 1982;155:1754–1765. doi: 10.1084/jem.155.6.1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaufmann S H E, Hahn H, Berger R, Kirchner H. Interferon-gamma production by Listeria monocytogenes-specific T cells active in cellular antibacterial immunity. Eur J Immunol. 1983;13:265–268. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830130318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaufmann S H E, Hahn H, Simon M M. T-cell subsets induced in Listeria monocytogenes-immune mice. Ly phenotypes of T cells interacting with macrophages in vitro. Scand J Immunol. 1982;16:539–542. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1982.tb00756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kaufmann S H E, Hug E, Väth U, Müller I. Effective protection against Listeria monocytogenes and delayed-type hypersensitivity to listerial antigens depend on cooperation between specific L3T4+ and Lyt 2+ T cells. Infect Immun. 1985;48:263–266. doi: 10.1128/iai.48.1.263-266.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaufmann S H E, Hug E, Vath U, De Libero G. Specific lysis of Listeria monocytogenes-infected macrophages by class II-restricted L3T4+ T cells. Eur J Immunol. 1987;17:237–246. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830170214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kaufmann S H E, Rodewald H R, Hug E, De Libero G. Cloned Listeria monocytogenes specific non-MHC-restricted Lyt-2+ T cells with cytolytic and protective activity. J Immunol. 1988;140:3173–3179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ladel C H, Blum C, Kaufmann S H E. Control of natural killer cell-mediated innate resistance against the intracellular pathogen Listeria monocytogenes by gamma/delta T lymphocytes. Infect Immun. 1996;64:1744–1749. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.5.1744-1749.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mielke M E A, Ehlers S, Hahn H. T-cell subsets in delayed-type hypersensitivity, protection, and granuloma formation in primary and secondary Listeria infection in mice: superior role of Lyt-2+ cells in acquired immunity. Infect Immun. 1988;56:1920–1925. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.8.1920-1925.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mielke M E, Niedobitek G, Stein H, Hahn H. Acquired resistance to Listeria monocytogenes is mediated by Lyt-2+ T cells independently of the influx of monocytes into granulomatous lesions. J Exp Med. 1989;170:589–594. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.2.589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mombaerts P, Arnoldi J, Russ F, Tonegawa S, Kaufmann S H E. Different roles of alpha beta and gamma delta T cells in immunity against an intracellular bacterial pathogen. Nature. 1993;365:53–56. doi: 10.1038/365053a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Musaka, A., and W. Born. 1997. Unpublished data.

- 44.North R J. Cellular kinetics associated with the development of acquired cellular resistance. J Exp Med. 1969;130:299–314. doi: 10.1084/jem.130.2.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rhoades E R, Cooper A M, Orme I M. Chemokine response in mice infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3871–3877. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.10.3871-3877.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Roberts A D, Ordway D J, Orme I M. Listeria monocytogenes infection in β2 microglobulin-deficient mice. Infect Immun. 1993;61:1113–1116. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.3.1113-1116.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rogers H W, Unanue E R. Neutrophils are involved in acute, nonspecific resistance to Listeria monocytogenes in mice. Infect Immun. 1993;61:5090–5096. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.12.5090-5096.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rosen H, Gordon S, North R J. Exacerbation of murine listeriosis by a monoclonal antibody specific for the type 3 complement receptor of myelomonocytic cells. Absence of monocytes at infective foci allows Listeria to multiply in nonphagocytic cells. J Exp Med. 1989;170:27–37. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sasaki T, Mieno M, Udono H, Yamaguchi K, Usui T, Hara K, Shiku H, Nakayama E. Roles of CD4+ and CD8+ cells, and the effect of administration of recombinant murine interferon gamma in listerial infection. J Exp Med. 1990;171:1141–1154. doi: 10.1084/jem.171.4.1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Skeen M J, Ziegler H K. Induction of murine peritoneal gamma/delta T cells and their role in resistance to bacterial infection. J Exp Med. 1993;178:971–984. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.3.971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sperling U, Kaufmann S H E, Hahn H. Production of macrophage-activating and migration-inhibition factors in vitro by serologically selected and cloned Listeria monocytogenes-specific T cells of the Lyt 1+2− phenotype. Infect Immun. 1984;46:111–115. doi: 10.1128/iai.46.1.111-115.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Teixeira H C, Kaufmann S H E. Role of NK1.1+ cells in experimental listeriosis. NK1+ cells are early IFN-gamma producers but impair resistance to Listeria monocytogenes infection. J Immunol. 1994;152:1873–1882. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thoma-Uszynski S, Ladel C H, Kaufmann S H E. Abscess formation in Listeria monocytogenes-infected gamma delta T cell deficient mouse mutants involves alpha beta T cells. Microb Pathog. 1997;22:123–128. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1996.0095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wagner R D, Steinberg H, Brown J F, Czuprynski C J. Recombinant interleukin-12 enhances resistance of mice to Listeria monocytogenes infection. Microb Pathog. 1994;17:175–86. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1994.1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xiong H, Ohya S, Tanabe T, Mitsuyama M. Persistent production of interferon-gamma (IFN-gamma) and IL-12 is essential for the generation of protective immunity against Listeria monocytogenes. Clin Exp Immunol. 1997;108:456–462. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1997.4101301.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]