Abstract

The adhesive minor protein MrkD of the type 3 fimbria of Klebsiella pneumoniae was expressed and purified from Escherichia coli as a fusion protein with an N-terminal polyhistidine tail. Polyclonal antibodies raised against MrkD specifically recognized the MrkD peptide in Western blots of fimbrial preparations. Immunoelectron microscopic analyses showed that the anti-MrkD immunoglobulins bound to the tip of the plasmid-encoded variant of the type 3 fimbria of K. pneumoniae, whereas no binding to the chromosomally encoded MrkD-deficient type 3 fimbrial variant of K. pneumoniae was detected. Immunoglobulins from an antiserum raised against purified type 3 fimbrial filaments bound laterally to both type 3 fimbrial variants. The anti-MrkD antibodies also bound to the tip of a papG deletion derivative of the E. coli P fimbria complemented with mrkD, indicating that MrkD structurally complements a PapG mutation in the P fimbria of E. coli.

Type 3 fimbriae are expressed by most Klebsiella isolates associated with human urinary or respiratory tract infections (9, 17, 23). Klebsiella pneumoniae and Klebsiella oxytoca are opportunistic pathogens that cause complicated urinary tract infections in the elderly or in compromised hosts who have predisposing factors such as urinary catheters or primary infections caused by other microorganisms (17, 24). Klebsiella infections often occur in hospitalized patients and frequently lead to sepsis, as well as to chronic or recurrent urinary tract infections, and many Klebsiella isolates are resistant to a variety of antibiotics.

Type 3 fimbriae were originally characterized by their ability to hemagglutinate tannin-treated erythrocytes (3). At least six mrk genes are needed for the synthesis of the type 3 fimbrial filament; of these, the mrkA gene encodes the major fimbrillin and mrkD encodes the hemagglutinin (4, 6, 7). Recent evidence has shown that Klebsiella type 3 fimbriae occur in at least two variants, a plasmid-encoded one and a chromosomally encoded one (9, 21). The variants were first described in K. pneumoniae IA565 (9) and differ in that the chromosomally encoded variant lacks hemagglutination capacity, as well as the mrkD gene. The mrkD gene is present in the plasmid-borne mrk gene cluster and responsible for hemagglutination capacity (7, 9). Cloned mrkD complements the mrkD-deficient chromosomally encoded variant and restores the adhesive properties of the fimbriae (9). We have presented evidence that the MrkD adhesin of the plasmid-borne variant binds to type V collagen in basolateral aspects of renal tubuli, as well as in vessel walls (22). Such adhesiveness may increase the infectivity of klebsiellas at damaged tissue sites, e.g., in a catheterized urinary tract (17) or damaged regions in the lung (8, 10).

The plasmid-borne mrk gene cluster is similar in genetic organization to the pap gene cluster encoding the globoside-binding P (or Pap) fimbriae of uropathogenic Escherichia coli (reviewed in reference 11). The P fimbriae are the most important single virulence factor of pyelonephritis-associated E. coli (for a review, see reference 17). Both gene clusters contain genes for the major fimbrillin and the minor adhesin, as well as for a periplasmic chaperone and an outer membrane usher protein anchoring the fimbriae to the bacterial cell wall. The adhesive property of P fimbriae is carried on a tip-associated fibrillum that is composed of PapE, PapF, PapK, and the adhesive molecule PapG (16). It is not clear how well the structure of P fimbria serves as a model for other fimbrial filaments of gram-negative bacteria. Indeed, the mannose-binding FimH adhesin of the type 1 fimbria of E. coli has been detected as occurring laterally at intervals along the fimbrial filament in studies utilizing immunoelectron microscopy with a mannose-coupled carrier protein or antibodies specific for FimH (1, 15). On the other hand, a tip fibrillum highly similar to that described for P fimbriae has also been reported for the type 1 fimbria of E. coli (12).

As a step towards understanding the mechanism of adhesion displayed by the MrkD adhesin, we expressed and purified MrkD containing an N-terminal histidine tail. We used antibodies against purified MrkD in immunoelectron microscopy to locate the adhesin in the type 3 fimbrial filament of a recombinant E. coli and a wild-type K. pneumoniae strain. Gerlach et al. (7) have previously demonstrated that mrkD can complement a papG mutation to produce P fimbriae with an MrkD-specific binding function. We also demonstrate here that this complementation results in correct tip localization of MrkD in the P-fimbrial filament.

Bacterial strains and proteins.

For expression of cloned fimbrial genes, nonfimbriate E. coli LE392 (20) was used as the host strain. Plasmid pFK12 (4), containing the plasmid-borne mrk gene cluster of K. pneumoniae, was used for the expression of wild-type type 3 fimbriae. For expression of PapG-deficient P fimbriae, plasmid pDC17 (7), carrying a papG-deficient pap gene cluster, was used; the papG deletion in pDC17 was complemented in trans by plasmid pFK52 (7), which consists of the mrkD gene in plasmid pACYC184. The type 1 fimbriae of K. pneumoniae IA565 were expressed in E. coli LE392 by using plasmid pGG101 (5) carrying the fim gene cluster. For expression of wild-type type 3 fimbriae, K. pneumoniae IA565 (4), carrying a fim gene cluster, as well as an mrkD-deficient mrk gene cluster on the chromosome and a plasmid-borne mrkD-containing mrk gene cluster, was used. The bacteria were grown for 18 h at 37°C on Luria agar supplemented with ampicillin (75 μg/ml) or chloramphenicol (25 μg/ml), as appropriate. K. pneumoniae IApc35 (9), carrying the fim gene cluster, as well as an mrkD-deficient mrk gene cluster on the chromosome, was cultured on glycerol-Casamino Acids agar (8, 10) for 18 h at 37°C. Purified fimbriae of E. coli HB101(pFK12), HB101(pDC17), HB101(pFK52/pDC17), and HB101(pGG101) were available from previous work (22, 23). K. pneumoniae IApc35 fimbriae were purified by using deoxycholate and concentrated urea as described before (13). Rabbit antibodies against purified type 3 fimbriae were available from previous work (14).

Peptide synthesis and immunization.

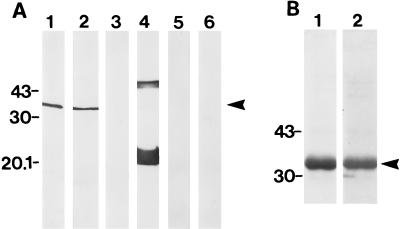

To have a tool for identification of MrkD in recombinant E. coli, we first raised an antipeptide serum that was specific for MrkD. Using solid-phase peptide synthesis on RapidAmide resin (Du Pont de Nemours, Dreieich, Germany) and 9-fluorenylmethyloxycarbonyl amino acid chemistry, we manually synthesized an 11-mer peptide corresponding to the predicted, potentially antigenic sequence 54-TLKSDAKVVA-63 of the mature MrkD protein (7) and added an extra cysteine at the C terminus for subsequent immunization. The full-length peptide was detached from the resin and purified by reverse-phase chromatography on a preparative PepRPC HR10/10 column (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) using an increasing gradient (0 to 0.1% [vol/vol]) of trifluoroacetic acid in acetonitrile as the eluent, and the homogeneity of the peptide was verified by amino acid sequencing in a gas-pulsed liquid-phase sequencer. The side chain of the C-terminal cysteine was reduced to thiol form, the deprotected peptide was coupled to the m-maleimidobenzoyl-N-hydroxysuccinimide-activated carrier protein keyhole limpet hemocyanin, and after desalting, the complex was used as an immunogen in rabbits in accordance with standard procedures (2). The anti-MrkD-antibody reacted in a Western blot with the denatured MrkD present in the type 3 fimbrial preparation (Fig. 1A). The specificity of the antibodies for the 34-kDa MrkD peptide was shown by their lack of binding to the 20.5-kDa MrkA peptide (lane 1 of Fig. 1A) that was strongly stained by the anti-type 3 fimbria antibodies (lane 4 of Fig. 1A). The antipeptide antibodies also detected MrkD in the purified LE392(pFK52/pDC17) fimbrial preparation, whereas the fimbriae of LE392(pDC17) did not react with the antibodies (lanes 2 and 3 in Fig. 1A, respectively). This indicates that MrkD forms an integral part of the PapG-deficient hybrid P fimbria purified from recombinant strain LE392(pFK52/pDC17). It was concluded that the antipeptide serum was specific enough to be used in the detection of MrkD expression in E. coli.

FIG. 1.

Immunoblotting of purified fimbriae and MrkD with antipeptide and antifimbria antibodies. (A) Reactivity of the fimbriae from E. coli LE392(pFK12) (lanes 1 and 4), LE392(pFK52/pDC17) (lanes 2 and 5), and LE392(pDC17) (lanes 3 and 6) with the anti-MrkD peptide (lanes 1 to 3) and anti-type 3 fimbria (lanes 4 to 6) antibodies. (B) Lane 1, SDS-PAGE analysis of purified MrkD; lane 2, Western blot of MrkD with the antipeptide antibodies. The arrowheads indicate the migration distance of MrkD. The values to the left of each panel are molecular sizes in kilodaltons.

Expression and purification of recombinant MrkD protein.

The anti-MrkD peptide antibody did not react with MrkD in immunoelectron microscopy or immunofluorescence assays with type 3 fimbrial filaments (data not shown). Therefore, we next expressed and purified a recombinant MrkD protein carrying an N-terminal polyhistidine tail. It was constructed by PCR cloning a 912-bp DNA fragment encoding mature MrkD into plasmid pQE30 (Qiagen). Plasmid pFK12 (4) was used as the template, oligonucleotides 5′CGCGGATCCTGGGCATCATGTTGGCAATC and 5′GGAAGCTTTTAATCGTACGTCAGGTTAAAG were used as primers, and the reading frames of both the polyhistidine-encoding sequence of pQE30 and the mrkD fragment were retained. After transformation into E. coli XL1-Blue MRF′ (Stratagene), a clone that produced large amounts of MrkD was identified by Western blotting with the antipeptide serum and named E. coli XL1-Blue(mrkD/pQE30). In a larger-scale purification of recombinant MrkD, late-log-phase bacteria were induced with 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) and cultured for an additional 5 h. The recombinant MrkD protein carried an N-terminal polyhistidine tail that efficiently binds to nickel ions and was purified from inclusion bodies of urea-treated cells by affinity chromatography on nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid resin (Qiagen). To wash out unbound or only loosely bound proteins, the column was washed with 8 M urea in 10 mM Tris-phosphate buffer in a decreasing pH gradient (pH 8.0 to 6.3) until the optical density at 280 nm reached zero. Column-bound protein was eluted by using 10 mM Tris-phosphate buffer (pH 5.9) containing 8 M urea and the histidine analog imidazole at 0.25 M. The fractions containing the 34-kDa MrkD protein were further purified on a Superose 12 HR10/30 gel filtration column (Pharmacia), and for renaturation, purified MrkD was dialyzed stepwise against decreasing concentrations of urea in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and finally against PBS. Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) analysis of the MrkD preparation is shown in Fig. 1B. Only one peptide, with an apparent molecular mass of 34 kDa, which is similar to the calculated molecular mass of the mrkD gene product, was detected. This peptide also reacted with the antipeptide antibodies (Fig. 1B), indicating that it indeed was MrkD.

Specificity of polyclonal anti-MrkD antibodies.

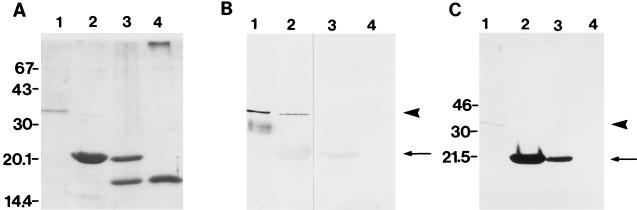

We immunized rabbits with purified recombinant MrkD in accordance with standard procedures (13) and assessed the specificity of these antibodies by Western blotting (Fig. 2). Purified MrkD (1 μg per lane) and Klebsiella type 1 and 3 fimbriae (25 to 100 μg per lane) were analyzed by SDS-PAGE using a 5% (wt/vol) stacking gel and a 15% separating gel (Fig. 2A). Polypeptides were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad) by using a semidry transfer apparatus (Pharmacia). The membranes were quenched with 2% bovine serum albumin in PBS, and the polypeptides were visualized by staining with specific primary antibodies (described below) diluted in 1% bovine serum albumin in PBS and alkaline phosphatase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Orion Diagnostica, Espoo, Finland) diluted 1:500. A phosphatase substrate containing nitroblue tetrazolium (Sigma) and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indoly-1-phosphate (Sigma) was used. The anti-MrkD protein antibodies (diluted 1:400) detected only a peptide with an apparent molecular mass equivalent to that of the mature MrkD peptide (34 kDa; lanes 1 and 2 in Fig. 2B) and failed to react with the MrkA (20.5 kDa) and FimA (apparent size, 18 kDa) peptides (lanes 2 to 4 in Fig. 2B). Furthermore, the anti-MrkD peptide antibody (diluted 1:100) did not react with the fimbrial preparation from K. pneumoniae IApc35 (lane 3 in Fig. 2B), which is in accordance with the reported lack of mrkD in this type 3 fimbria gene cluster (9, 22). The anti-type 3 fimbria antibodies (diluted 1:500) strongly detected the 20.5-kDa MrkA peptide (lanes 2 and 3 in Fig. 2C) but only weakly detected the 34-kDa MrkD peptide (lanes 1 and 2 in Fig. 2C). We also tested the reactivity of both antisera with the type 1 fimbriae of K. pneumoniae purified from recombinant E. coli LE392(pGG101); neither antiserum gave a detectable reaction with the Fim peptides (lane 4 in Fig. 2B and C).

FIG. 2.

Immunoblotting of purified MrkD and fimbriae with anti-MrkD and anti-type 3 fimbria antibodies. (A) SDS-PAGE of purified MrkD (lane 1) and fimbriae from E. coli LE392(pFK12) (lane 2), K. pneumoniae IApc35 (lane 3), and E. coli LE392(pGG101) (lane 4). The migration distances of molecular size standard proteins (sizes are in kilodaltons) are indicated on the left. Immunoblotting of the antigens with anti-MrkD antibodies is shown in panel B, and immunoblotting with anti-type 3 fimbria serum is shown in panel C. The arrowheads indicate the position of MrkD, and the arrows indicate that of MrkA.

Immunoelectron microscopy.

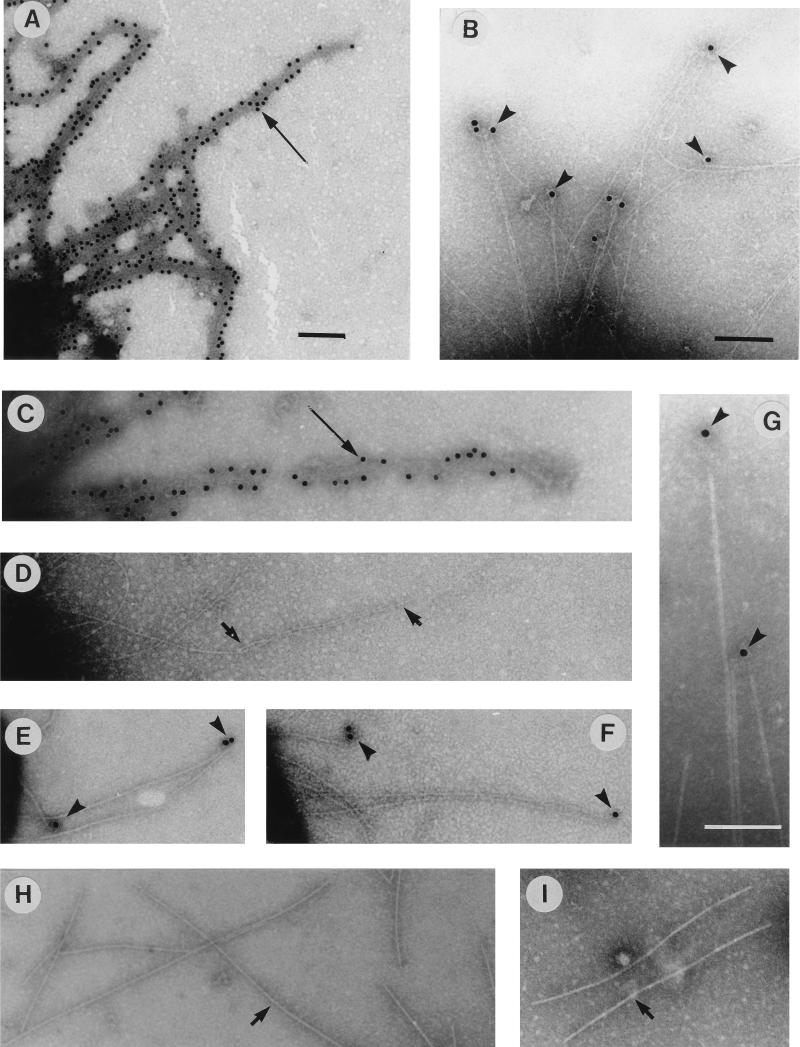

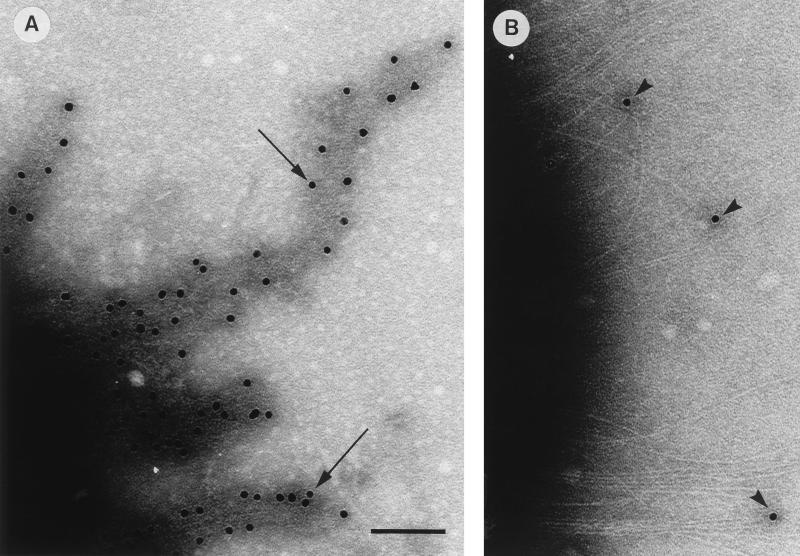

To locate the MrkD protein in the type 3 fimbrial filament, we used immunoelectron microscopy (Fig. 3 and 4). Bacterial cells expressing the various fimbriae were immobilized on copper grids and allowed to react with antibodies against type 3 fimbriae (diluted 1:500) or recombinant MrkD (diluted 1:300) for 90 min at 20°C. Bound antibodies were visualized with an Auroprobe EM protein A conjugate diluted 1:50 (Amersham). Bacteria were negatively stained by 1% sodium tungstic acid (NaPT), pH 7.0, for 40 s. The grids were examined in a JEOL JEM-1200EX transmission electron microscope at an operating voltage of 60 kV. The type 3 fimbriae on E. coli LE392(pFK12) bound anti-type 3 fimbria antibodies laterally (Fig. 3A), whereas the anti-MrkD antibodies were detected exclusively at the fimbrial tips (Fig. 3B). E. coli LE392 carrying only the cloning vector did not react with the antibodies (data not shown). The MrkD-deficient type 3 fimbriae from strain IApc35 reacted with the anti-type 3 fimbria antibodies (Fig. 3C), whereas the anti-MrkD protein antibodies did not bind to the IApc35 fimbriae (Fig. 3D). Recombinant strain LE392(pFK52/pDC17) reacted similarly with both antisera: binding of the antibodies was detected exclusively at the fimbrial tips (Fig. 3E and F). Under higher magnification, the gold particles were visualized at sites where a weakly electron-dense structure separated them from the bulk of the P-fimbrial filament (Fig. 3G). This tip-associated structure was difficult to visualize by negative staining and very likely corresponds to the tip fibrillum of the P fimbriae (16). The PapG-deficient P fimbriae from strain LE392(pDC17) without the mrkD complementation did not bind the antibodies (Fig. 3H and I). The type 3 fimbriae of wild-type K. pneumoniae IA565 showed binding of antibodies identical to that of type 3 fimbriae of E. coli LE392(pFK12) (Fig. 4). Anti-type 3 fimbria antibodies bound laterally to the fimbriae (Fig. 4A), whereas anti-MrkD protein antibodies bound exclusively to the tips of the fimbriae (Fig. 4B).

FIG. 3.

Immunoelectron microscopy of fimbrial antigens with anti-type 3 fimbria serum (A, C, E, and H) and with anti-MrkD antibodies (B, D, F, G, and I). The bacteria are E. coli LE392(pFK12) (A and B), K. pneumoniae IApc35 (C and D), E. coli LE392(pFK52/pDC17) (E to G), and E. coli LE392(pDC17) (H and I). Arrowheads indicate binding of antibodies and protein A-gold to tips of fimbrial filaments, long arrows indicate binding along the fimbrial filament, and short arrows indicate lack of binding. Bars, 100 nm.

FIG. 4.

Immunoelectron microscopy of fimbrial antigens of K. pneumoniae IA565 with anti-type 3 fimbria serum (A) and anti-MrkD protein antibodies (B). Arrowheads indicate binding of antibodies and protein A-gold to tips of fimbrial filaments, and long arrows indicate binding along the fimbrial filament. Bar, 100 nm.

Our results demonstrate that the MrkD minor adhesin of the type 3 fimbrial filaments of K. pneumoniae is localized at the tip of the fimbrial filaments. The organization of the type 3 fimbrial filaments thus greatly resembles that of the P fimbriae of uropathogenic E. coli (11), which remains the best-characterized fimbrial type in regard to genetics and biosynthesis. Our results also demonstrate that mrkD complements a papG mutation resulting in a P-fimbrial filament with MrkD located at the tip of the filament. This indicates a high degree of similarity in the biogenesis and structural constraints within the two filaments.

We demonstrated the tip orientation of MrkD in type 3 fimbriae expressed on both a recombinant and a wild-type strain by immunoelectron microscopy with highly specific anti-MrkD antibodies. The antibodies were raised against MrkD purified from the cytoplasm of E. coli that expressed MrkD with an N-terminal polyhistidine tail. The resulting fusion protein was of the correct size and reacted with antibodies raised against a synthetic peptide mimicking an antigenic site in the MrkD sequence. The antibodies obtained by immunization with purified MrkD reacted exclusively with the tip of the type 3 fimbrial filament, whereas antibodies raised by immunization with purified type 3 fimbriae reacted along the sides of the fimbrial filament. The specificity of the anti-MrkD antibodies was demonstrated in a Western blot by their lack of reactivity with the 20.5-kDa MrkA peptide in the type 3 fimbrial preparations, as well as with the 18-kDa type 1 fimbrial peptides of K. pneumoniae. Furthermore, the type 3 fimbriae from K. pneumoniae IApc35, whose chromosome does not hybridize with mrkD and which does not exhibit the MrkD-mediated hemagglutination of tanned erythrocytes (9, 21), failed to react with the anti-MrkD antibodies in a Western blot and in immunoelectron microscopy. This strongly suggests that the anti-MrkD antibodies recognized only the 34-kDa MrkD peptide in the fimbrial filaments. In contrast, the anti-type 3 fimbria antibodies reacted with the 20.5-kDa MrkA peptide in a Western blot and bound similarly to both type 3 fimbrial filaments. This indicates that the major MrkA subunits in the two type 3 fimbrial variants are immunologically cross-reactive. It is impossible to say whether the chromosomal type 3 fimbrial variant on strain IApc35 completely lacks mrkD or whether it carriers a variant adhesin that is genetically and structurally unrelated to MrkD. The latter situation has been detected in the PapG variants of uropathogenic E. coli (18).

Gerlach et al. (7) found that mrkD complements a papG mutation in the P fimbria of E. coli. The complemented strain is able to hemagglutinate (7) and to bind to type V collagen (22), which indicates that MrkD has a functionally correct conformation on the E. coli surface. It was not, however, assessed whether MrkD in this construct actually is associated with the fimbriae or whether it is just transported to the outer membrane by the P-fimbrial biosynthetic machinery. Our results indicate that MrkD is located at the tip of the P-fimbrial filament and that it also has a correct structural localization in the tip fibrillum (16) of the hybrid fimbria. It should be noted that the hybrid fimbriae shown in Fig. 1 were purified by using deoxycholate and concentrated urea. The fact that the hybrid fimbriae could stand these agents indicates strong interactions between the components of the tip fibrillum. The structurally and functionally correct complementation of papG by mrkD actually is surprising in terms of the different primary structures of the two adhesins. The molecular size of PapG is 38.3 kDa, and that of MrkD is 34.0 kDa, and their amino acid sequences are only 12% identical. This suggests that shared dominant features in the structure of the minor components, rather than their primary structure, are important in the biogenesis of the P fimbria. The chaperone proteins PapD and MrkB show only a low level of sequence similarity but share the few critical amino acid residues that are considered important for the structure and correct folding of PapD (11).

The present and previous (7, 22) results demonstrate that the plasmid-encoded type 3 fimbria of K. pneumoniae and the P fimbria of E. coli share structural similarity and probably represent evolutionarily related fimbrial types. We have recently found (19) that in the G (F17) fimbrial filament, the GafD lectin is also tip associated but the gafD lectin gene cannot complement the papG mutation we used here. Hence G fimbriae, despite their overall morphological similarity to P fimbriae, may represent another type of organization of fimbrial subunits in E. coli.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Academy of Finland (projects 29346 and 1511) and the University of Helsinki.

We thank Marc Baumann for performing amino acid sequence analyses, Raili Lameranta for technical assistance, and Steven Clegg and Doug Hornick for the Klebsiella strains.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abraham S N, Goguen J D, Sun D, Klemm P, Beachey E H. Identification of two ancillary subunits of Escherichia coli type 1 fimbriae by using antibodies against synthetic oligopeptides of fim gene products. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:5530–5536. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.12.5530-5536.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coligan J H, Kruisbeek A M, Margulies D H, Shevach E M, Strober W. Current protocols in immunology. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duguid J P. Fimbriae and adhesive properties in Klebsiella strains. J Gen Microbiol. 1959;21:271–286. doi: 10.1099/00221287-21-1-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gerlach G-F, Clegg S. Cloning and characterization of the gene cluster encoding type 3 (MR/K) fimbriae of Klebsiella pneumoniae. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1988;49:377–383. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gerlach G-F, Clegg S. Characterization of two genes encoding antigenically distinct type-1 fimbriae of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Gene. 1988;64:231–240. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90338-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gerlach G-F, Allen B L, Clegg S. Molecular characterization of the type 3 (MR/K) fimbriae of Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:3547–3553. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.8.3547-3553.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gerlach G-F, Clegg S, Allen B L. Identification and characterization of the genes encoding the type 3 and type 1 fimbrial adhesins of Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:1262–1270. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.3.1262-1270.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hornick D B, Allen B L, Horn M A, Clegg S. Adherence to respiratory epithelia by recombinant Escherichia coli expressing Klebsiella pneumoniae type 3 fimbrial gene products. Infect Immun. 1992;60:1577–1588. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.4.1577-1588.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hornick D B, Thommandru J, Smits W, Clegg S. Adherence properties of an mrkD-negative mutant of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2026–2032. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.5.2026-2032.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hornick D B, Allen B L, Horn M A, Clegg S. Fimbrial types among respiratory isolates belonging to the family Enterobacteriaceae. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:1795–1800. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.9.1795-1800.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hultgren S J, Normark S, Abraham S N. Chaperone-assisted assembly and molecular architecture of adhesive pili. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1991;45:383–415. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.45.100191.002123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones C H, Pinkner J S, Roth R, Heuser John, Nicholes A V, Abraham S N, Hultgren S J. FimH adhesin of type 1 pili is assembled into a fibrillar tip structure in the Enterobacteriaceae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:2081–2085. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.6.2081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Korhonen T K, Nurmiaho E-L, Ranta H, Svanborg-Edén C. New method for isolation of immunologically pure pili from Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1980;27:569–575. doi: 10.1128/iai.27.2.569-575.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Korhonen T K, Tarkka E, Ranta H, Haahtela K. Type 3 fimbriae of Klebsiella sp.: molecular characterization and role in bacterial adhesion to plant roots. J Bacteriol. 1983;155:860–865. doi: 10.1128/jb.155.2.860-865.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krogfelt K, Bergmans H, Klemm P. Direct evidence that the FimH protein is the mannose-specific adhesin of Escherichia coli type 1 fimbriae. Infect Immun. 1990;58:1995–1998. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.6.1995-1998.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuehn M J, Heuser J, Normark S, Hultgren S. P pili of uropathogenic Escherichia coli are composite fibres with distinct fibrillar adhesive tips. Nature. 1992;356:252–255. doi: 10.1038/356252a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kunin C M. Detection, prevention, and management of urinary tract infections. Philadelphia, Pa: Lea & Febiger; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lund B, Marklund B-I, Strömberg N, Lindberg F, Karlsson K-A, Normark S. Uropathogenic Escherichia coli can express serologically identical pili of different receptor binding specificities. Mol Microbiol. 1988;2:255–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1988.tb00027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saarela, S., J. Tanskanen, N. Kalkkinen, B. Westerlund-Wikström, M. Rhen, and T. K. Korhonen. Unpublished data. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schurtz T A, Hornick D B, Korhonen T K, Clegg S. The type 3 fimbrial adhesin gene (mrkD) is not conserved among all fimbriate strains. Infect Immun. 1994;62:4186–4191. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.10.4186-4191.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tarkkanen A-M, Allen B L, Westerlund B, Holthöfer H, Kuusela P, Risteli L, Clegg S, Korhonen T K. Type V collagen as the target for type-3 fimbriae, enterobacterial adherence organelles. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:1353–1361. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb00714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tarkkanen A-M, Allen B L, Williams P H, Kauppi M, Haahtela K, Siitonen A, Ørskov I, Ørskov F, Clegg S, Korhonen T K. Fimbriation, capsulation, and iron-scavenging systems of Klebsiella strains associated with human urinary tract infection. Infect Immun. 1992;60:1187–1192. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.3.1187-1192.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Williams P, Tomas J M. The pathogenicity of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Rev Med Microbiol. 1990;1:196–204. [Google Scholar]