Abstract

Virulent and attenuated Brucella abortus strains attach to and penetrate nonprofessional phagocytic HeLa cells. Compared to pathogenic Brucella, the attenuated strain 19 hardly replicates within cells. The majority of the strain 19 bacteria colocalized with the lysosome marker cathepsin D, suggesting that Brucella-containing phagosomes had fused with lysosomes, in which they may have degraded. The virulent bacteria prevented lysosome-phagosome fusion and were found distributed in the perinuclear region within compartments resembling autophagosomes.

The genus Brucella consists of facultative intracellular gram-negative bacteria that infect humans and animals (4), causing brucellosis, a disease that occurs worldwide and is endemic in many underdeveloped countries (39). During the course of infection, professional phagocytes are the first target for Brucella invasion (4, 23, 27, 34), and the bacteria can survive within these cells. Despite their tropism for the sexual organs, these bacteria can also be found in bones, joints, the eyes, and the brain (14). In vitro, Brucella abortus replicates in both the epitheloid HeLa and the fibroblastic Vero cell lines (9, 17). Smooth virulent B. abortus strains replicate intracellularly more efficiently than smooth attenuated strain 19 or rough strains. Inhibition of phagosome-lysosome fusion has been proposed as a mechanism used by B. abortus for intracellular survival (16). It has been suggested that in trophoblasts of pregnant ruminants (1) as well as in Vero cells, pathogenic B. abortus replicates within the rough endoplasmic reticulum (RER) (9), and transfer from phagosomes to RER was proposed to be a limiting step in Brucella infection (10, 11). However, the identity of compartments where the bacteria replicate or are destroyed is still a matter of debate.

In this study, we established a protocol of infection based on the inoculation of 500 bacteria per HeLa cell for 4 h. Log-phase cultures of virulent smooth B. abortus 544 and 2308 (provided by J.-M. Verger, INRA, Nouzilly, France) and attenuated smooth B. abortus 19 (Professional Biological Co., Denver, Colo.) were prepared by incubating 5 × 1010 CFU in 5 ml of tryptic soy broth for 15 h at 37°C. Subconfluent monolayers of HeLa cells cultured in 24-well tissue culture plates were inoculated with bacteria diluted to 108 CFU/ml in Dulbecco minimal essential medium (DMEM; GIBCO, Paisley, Scotland) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) and 2 mM glutamine without antibiotics (cell culture medium). Plates were centrifuged for 10 min at 1,000 rpm at room temperature and placed in a 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37°C. After 4 h, wells were washed five times with DMEM and further incubated with DMEM supplemented with 5% FCS–100 μg of gentamicin (Sigma, Saint Quentin Fallavier, France) per ml to kill remaining extracellular brucellae. The number of intracellular viable B. abortus CFU was determined at different times postinfection (p.i.) after the monolayers were washed twice with DMEM and once with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.4) and treated for 10 min with 1 ml of 0.1% Triton X-100 (Sigma) in deionized water (13). Lysates were serially diluted and plated on tryptic soy agar dishes for quantitation of CFU.

The intracellular and extracellular brucellae and the lysosomal marker cathepsin D were analyzed by confocal microscopy after immunofluorescence labelling (10, 22). Cells were extensively washed to remove nonadherent bacteria prior to fixation for 15 min with 3% paraformaldehyde in PBS, washed once in PBS, and incubated for 10 min with PBS-NH4Cl (50 mM) to quench free aldehyde groups. Extracellular bacteria were detected by incubation of the cells for 30 min with serum (diluted 1/10,000 in PBS–10% horse serum) from a B. abortus-infected cow (30) and revealed by donkey Texas red-conjugated anti-cow immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies (Immunotech, Marseille, France). For detection of intracellular bacteria, cells were further permeabilized with 0.05% saponin (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.), incubated for 30 min with serum (used at 1/5,000 dilution in PBS–10% horse serum) from a B. abortus-infected goat, and revealed with donkey fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-goat IgG antibodies (Immunotech). Cathepsin D was revealed with rabbit anti-cathepsin D antibodies (obtained from S. Kornfeld, St. Louis, Mo.) revealed with donkey cyanin 5-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG antibodies (Immunotech). Samples mounted in Mowiol (25) were observed with a Leica TCS 4DA confocal laser scanning microscope by analyzing cells and bacteria by reflection and fluorescence, respectively. For electron microscopy, HeLa cells infected with B. abortus 2308 were fixed with 2% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer for 30 min at 4°C, postfixed in OsO4, and processed for embedding in Epon 812 resin.

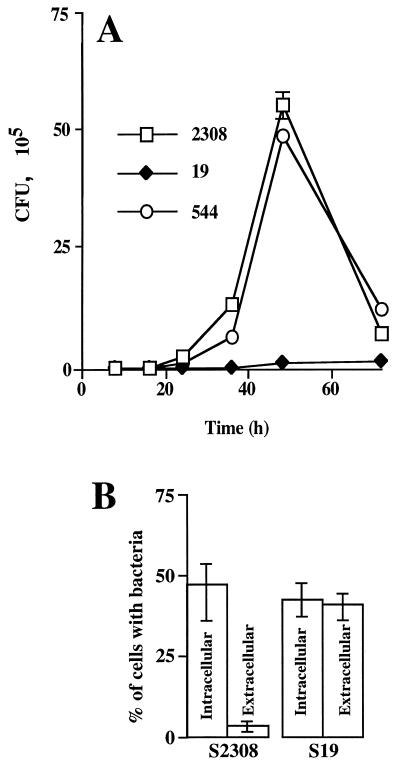

After an initial decrease in the number of bacteria between 4 and 8 h p.i. (data not shown), the number of strain 2308 and strain 544 bacteria increased slightly from 8 to 24 h (Fig. 1A). Then replication became faster between 24 and 36 h, and the highest rate of bacterial growth was detected between 36 and 48 h p.i. Between 4 and 48 h p.i., the percentage of the input inoculum recovered ranged from 0.003 to 1.62% for strain 2308 and from 0.004 to 1.41% for strain 544. In contrast, strain 19 replicated very slowly (Fig. 1A). Indeed, the percentage of recovered input inoculum changed from 0.003 to only 0.03% in the same period of time. Between 48 and 72 h p.i., the growth of strains 2308 and 544 dropped dramatically due to the breakdown of the plasma membrane of heavily infected cells and contact of released bacteria with gentamicin in the incubating medium. To determine whether the deficient replication of strain 19 within cells was due to failure in bacterial adherence or to a low penetration rate, the immunofluorescence assay for detecting extracellular and intracellular bacteria, described above, was performed. Figure 1B shows that both the attenuated and the pathogenic strains adhered to the cell surface and penetrated. However, the efficiency of invasion (Fig. 1B) of the pathogenic strain was greater than that of the attenuated strain, since at 4 h postinoculation almost all strain 2308 bacteria were found within cells, while approximately 50% of strain 19 bacteria remained extracellular (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

Kinetics of B. abortus replication. (A) Monolayers of HeLa cells were inoculated with attenuated strain 19 or virulent strains 544 and 2308 for 4 h at 37°C. After gentamicin treatment, the number of CFU of brucellae were determined. Values are averages ± standard errors for triplicate samples. (B) Quantification of extracellular and intracellular bacteria was performed by double immunofluorescence staining after 1 h of incubation at 37°C with 108 CFU of attenuated strain 19 or virulent strain 2308. Experiments were done in triplicate and repeated at least three times (approximately 500 intracellular and extracellular bacteria were counted per strain).

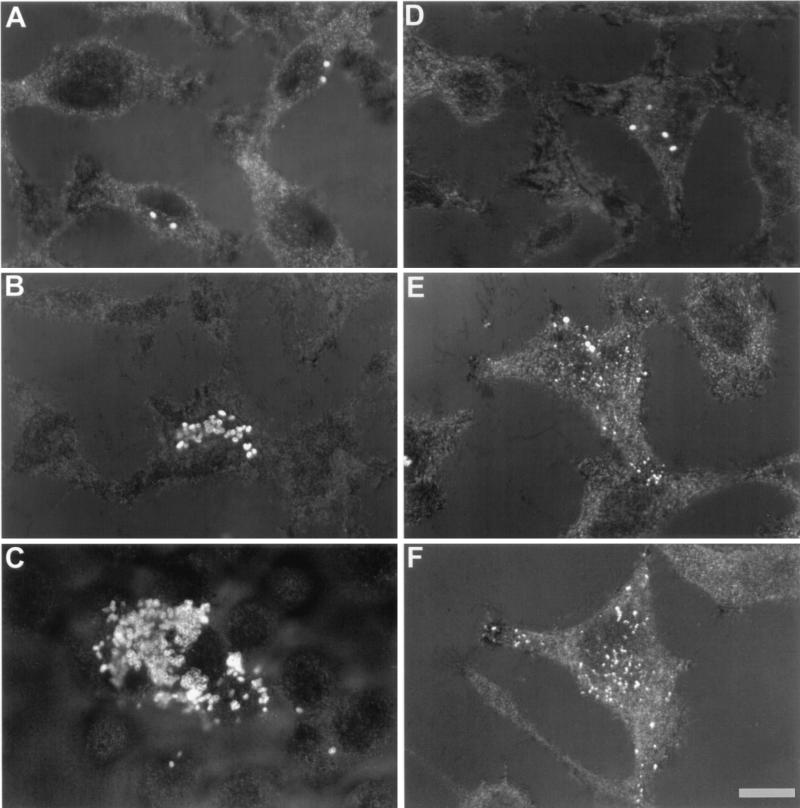

Next we explored the intracellular traffic of the various Brucella strains. At 4 h p.i., from 1 to 3 intracellular bacteria from strain 2808 and strain 19 were detected in each infected cell (Fig. 2A and D). At 24 h p.i., cells infected with virulent strain 2308 showed a significant increase in the number of intracellular bacteria in the perinuclear region (Fig. 2B). In contrast, in cells infected with strain 19, a small number of intact bacteria together with bacterial degradation products scattered throughout the cytoplasm were observed (Fig. 2E and F). At 72 h p.i., cells infected with virulent strains were filled with intracellular bacteria. In addition, some heavily infected cells broke down, leading to a release of free bacteria in the cell culture medium (Fig. 2C).

FIG. 2.

B. abortus replication assessed by confocal microscopy. After fixation, permeabilization, and immunolabelling of bacteria, HeLa cells were observed by analyzing reflection and fluorescence of cells and bacteria, respectively. Superimposed images of reflection and fluorescence are presented. (A, B, and C) Cells were infected with strain 2308 and observed at 4, 24, and 72 h p.i., respectively. (D, E, and F) Cells were infected with strain 19 and observed at the above-mentioned times, respectively. Bar, 10 μm.

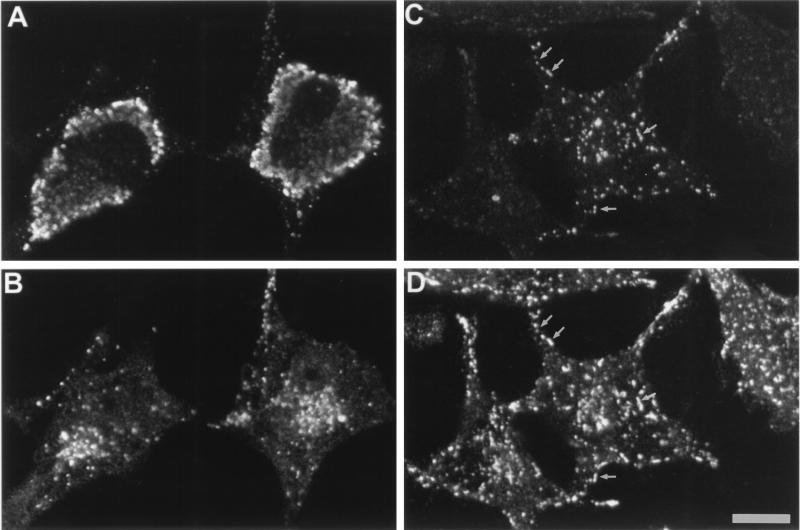

Indirect methods have suggested that pathogenic Brucella is capable of avoiding phagosome-lysosome fusion in macrophages (16). Therefore, to directly assess this hypothesis in nonprofessional phagocytic HeLa cells, we used double immunofluorescence (25). At 48 h p.i., cathepsin D, a well-known marker for lysosomes, was colocalized with phagosomes containing strain 19 and its degradation products (Fig. 3C and D), indicating that phagosomes had fused with lysosomes. In contrast, intracellular strain 2308 never colocalized with cathepsin D (Fig. 3A and B), indicating that those bacteria avoided fusion with lysosomes.

FIG. 3.

Cathepsin D in B. abortus vacuoles analyzed by double immunofluorescence. HeLa cells were immunostained to localize both Brucella (A and C) and cathepsin D (B and D). Double immunofluorescence micrographs show that strain 2308 does not colocalize with cathepsin D (A and B), whereas in strain 19-infected cells few remaining bacteria or bacterial degradation products colocalize with the lysosomal marker (C and D) as indicated by arrows. Bar, 10 μm.

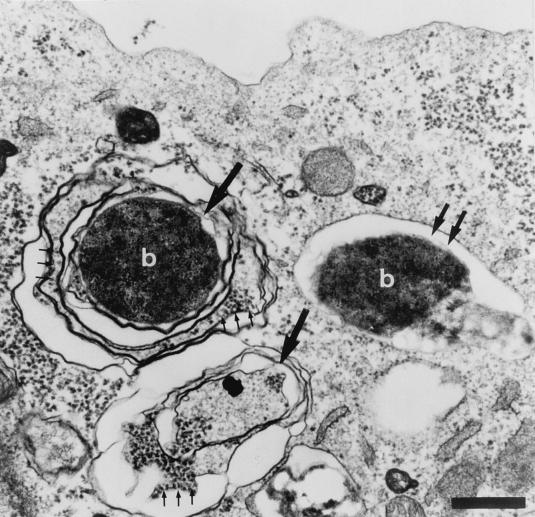

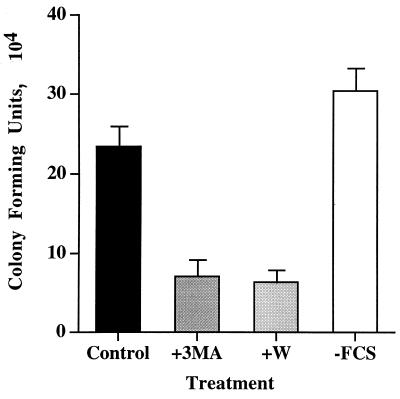

Since pathogenic B. abortus has been reported to replicate within the RER (9), we analyzed the characteristics of the Brucella intracellular compartment by electron microscopy. Electron micrographs show that at 24 h p.i., bacteria from strain 2308 were localized in two different membrane structures (Fig. 4). Some bacteria were found in phagosomes surrounded by a single membrane, and others were found in compartments resembling multimembranous autophagosomes (12) that were characterized by the presence of ribosomes (Fig. 4). To further investigate the possible involvement of autophagy in B. abortus infection, we tested the action of autophagic inhibitors. Several inhibitors of the autophagic machinery have been identified. Both 3-methyladenine and wortmannin inhibit autophagy by blocking phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activity (5, 31). In contrast, autophagy can be increased by limiting amounts of amino acids (32), and maximal levels of autophagy can be reached in as little as 20 min after amino acid withdrawal (32). For autophagic inhibition, cells were incubated for 15 min with cell culture medium in the presence of 3-methyladenine (10 mM) or wortmannin (100 nM). For autophagic activation, cells were grown in serum–glutamine-free cell culture medium for 15 min. Cells were inoculated with strain 2308 bacteria, incubated for 1 h with drugs or without FCS-glutamine, washed twice, and further incubated with cell culture medium supplemented with 100 μg of gentamicin per ml. At 24 h postinoculation, cells were lysed and CFU were estimated as described below. In the presence of autophagic inhibitors, fewer strain 2308 CFU were recovered from treated cells than from untreated cells (Fig. 5). The low bacterial yields observed were not due to the inhibition of bacterial replication by irreversible effects of drugs on HeLa cells, since monolayers infected after drug withdrawal showed viable bacterial counts similar to those of nontreated control cells (data not shown). Moreover, equal numbers of intracellular bacteria were found in drug-treated and untreated cells during the first hour of inoculation (data not shown), suggesting that drugs were acting on a critical step involving the accessibility of bacteria to the autophagic vacuoles or the intracellular replication compartment. When autophagy was increased by depleting cell culture medium of FCS and glutamine for 15 min and cells were infected for 1 h in the presence of the starving cell culture medium, an increase in the number of CFU recovered 24 h after infection was observed (Fig. 5). These results suggest that autophagy is important for the bacteria to reach their final intracellular multiplication compartment.

FIG. 4.

B. abortus 2308 is associated with autophagosome-like structures. At 24 h p.i., HeLa cells were processed for electron microscopy. An electron micrograph shows two multimembranous autophagosomal structures (large arrows), one of which contains the bacterium (b). Three small arrows indicate the presence of ribosomes. Double arrows show the presence of a phagosome containing one bacterium (6) surrounded by a single membrane with no ribosomes. Bar, 1 μm.

FIG. 5.

Modulation of autophagy affects B. abortus 2308 infection. HeLa cells were incubated with or without 3-methyladenine (+3MA; 10 mM) or wortmannin (W; 10 nm) or without FCS-glutamine for 15 min before bacterial inoculation. Then the cells were infected with strain 2308 for 1 h with or without drugs or without FCS, washed, and further incubated with fresh cell culture medium supplemented with gentamicin for 23 h. Cells were lysed, and the number of CFU were estimated. Inhibition of autophagy by 3-methyladenine or wortmannin significantly (P < 0.01%) reduces the number of isolated viable intracellular strain 2308, while starvation conditions without FCS increase the bacterial yield at 24 h postinoculation. Columns represent the averages of triplicate treatments ± standard deviations.

Our results, together with the results of previous studies (9, 11, 16), demonstrate that virulent Brucella need to evade lysosome fusion to multiply inside professional and nonprofessional phagocytes. Other pathogenic bacteria are known to avoid fusion with lysosomes as has been demonstrated with Mycobacterium avium and Mycobacterium tuberculosis (6–8). Legionella is another intracellular pathogen that is well adapted to life inside phagosomes. As for Mycobacterium, the phagosome containing Legionella is not acidified (20, 37), and at later stages of infection, vacuoles are found in the vicinity of the RER (19, 38).

Our results indicate that the efficiency of intracellular replication, but not of adherence to cells, correlates with the virulence of various B. abortus strains as in other cell types. Indeed, strain 2308 has been shown to persist longer in mice than strain 19 (3, 36) and replicates more efficiently than rough strain 45/20 or strain 19 in bovine mammary gland macrophages (18) and murine peritoneal macrophages (21). Strain 544 has also been shown to survive intracellularly better than strain 45/20 (33). It is clear that the attenuated strain 19 can invade cells but multiplies poorly because the bacteria degrade after the Brucella-containing phagosomes fuse with lysosomes. In contrast, virulent strain 2308 possesses mechanisms to escape lysosomal degradation. This characteristic seems to be independent of cell surface adherence, since strain 19 bacteria were able to adhere at higher levels than strain 2308 bacteria (Fig. 1B). This difference in adherence cannot yet be related to a difference in the compositions of the outer membrane components, since those of smooth virulent strain 2308 and smooth attenuated strain 19 are very similar (9, 15, 24, 30). The O-chain of the lipopolysaccharide (LPS) has been implicated as a key moiety for intracellular survival, as smooth strains are more resistant to intracellular killing in phagocytic cells (22, 29) and more resistant to the action of lysosomal bactericidal substances (24). However, as previously proposed (28), the O-chain of LPS cannot be the only factor correlated with intracellular survival, since the pathogenic strains 2308 and 544 and the attenuated strain 19 behave quite differently in HeLa cells despite their indistinguishable smooth LPS (2, 15). The decreased virulence of strain 19 has been attributed to its inability to metabolize erythritol (35), the only genetic defect characterized in this attenuated strain. We cannot rule out the possibility that changes in erythritol metabolism are responsible for the observed difference in intracellular replication between virulent and attenuated strains. However, other yet-unknown defects might be involved, since pathogenic erythritol-negative Brucella strains have been previously identified (26). More work is needed to determine which components in strain 19 are responsible for its increased adherence. Therefore, virulence seems to reflect the ability of pathogenic Brucella to persist and replicate within specific intracellular compartments.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from INSERM (4N004B) and institutional grants from INSERM and CNRS, LNFCC des Bouches du Rhône. J. Pizarro-Cerdá received a fellowship from CNRS.

We thank J. Ewbank and S. Méresse for critically reading the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson T D, Cheville N F. Ultrastructural morphometric analysis of Brucella abortus-infected trophoblasts in experimental placentitis. Bacterial replication occurs in rough endoplasmic reticulum. Am J Pathol. 1986;124:226–237. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aragón V R, Díaz R, Moreno E, Moriyón I. Characterization of Brucella abortus and Brucella melitensis native haptens as outer membrane O-type polysaccharides independent from the smooth lipopolysaccharide. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:1070–1079. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.4.1070-1079.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Araya L N, Elzer P H, Rowe G E, Enright F M, Winter A J. Temporal development of protective cell-mediated and humoral immunity in BALB/c mice infected with Brucella abortus. J Immunol. 1989;143:3330–3337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baldwin C L, Winter A J. Macrophages and Brucella. Immunol Ser. 1994;60:363–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blommaart E F C, Krause U, Shellens J P M, Vreeling-Sindelarova H, Meijer A J. The phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibitors wortmannin and LY294002 inhibit autophagy in isolated rat hepatocytes. Eur J Biochem. 1997;243:240–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.0240a.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clemens D L. Characterization of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis phagosome. Trends Microbiol. 1996;4:113–118. doi: 10.1016/0966-842X(96)81528-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clemens D L, Horwitz M A. Characterization of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis phagosome and evidence that phagosomal maturation is inhibited. J Exp Med. 1995;181:257–270. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.1.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Chastellier C, Lang T, Thilo L. Phagocytic processing of the macrophage endoparasite, Mycobacterium avium, in comparison to phagosomes which contain Bacillus subtilis or latex beads. Eur J Cell Biol. 1995;68:167–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Detilleux P G, Deyoe B L, Cheville N F. Entry and intracellular localization of Brucella spp. in Vero cells: fluorescence and electron microscopy. Vet Pathol. 1990;27:317–328. doi: 10.1177/030098589002700503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Detilleux P G, Deyoe B L, Cheville N F. Penetration and intracellular growth of Brucella abortus in nonphagocytic cells in vitro. Infect Immun. 1990;58:2320–2328. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.7.2320-2328.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Detilleux P G, Deyoe B L, Cheville N F. Effect of endocytic and metabolic inhibitors on the internalization and intracellular growth of Brucella abortus in Vero cells. Am J Vet Res. 1991;52:1658–1664. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dunn W A. Autophagy and related mechanisms of lysosome-mediated protein degradation. Trends Cell Biol. 1994;4:139–143. doi: 10.1016/0962-8924(94)90069-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elsinghorst E A. Measurement of invasion by gentamicin resistance. Methods Enzymol. 1994;236:405–420. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(94)36030-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Enright F M. The pathogenesis and pathobiology of Brucella infection in domestic animals. Antigens of Brucella. In: Nielsen K, Duncan B, editors. Animal brucellosis. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press, Inc; 1990. pp. 301–320. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Freer E, Moreno E, Moriyon I, Pizarro-Cerdá J, Weintraub A, Gorvel J P. Brucella-Salmonella lipopolysaccharide chimeras are less permeable to hydrophobic probes and more sensitive to cationic peptides and EDTA than their native Brucella sp. counterparts. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:5867–5876. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.20.5867-5876.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frenchick P J, Markham R J F, Cochrane A H. Inhibition of phagosome-lysosome fusion in macrophages by soluble extracts of virulent Brucella abortus. Am J Vet Res. 1985;46:332–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Halling S M, Detilleux P G, Tatum F M, Judge B A, Mayfield J E. Deletion of the BCSP31 gene of Brucella abortus by replacement. Infect Immun. 1991;59:3863–3868. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.11.3863-3868.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harmon B G, Adams L G, Frey M. Survival of rough and smooth strains of Brucella abortus in bovine mammary gland macrophages. Am J Vet Res. 1988;49:1092–1097. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Horwitz M A. The Legionnaires’ disease bacterium (Legionella pneumophila) inhibits phagosome-lysosome fusion in human monocytes. J Exp Med. 1983;158:2108–2126. doi: 10.1084/jem.158.6.2108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Horwitz M A, Maxfield F R. Legionella pneumophila inhibits acidification of its phagosome in human monocytes. J Cell Biol. 1984;99:1936–1943. doi: 10.1083/jcb.99.6.1936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones S M, Winter A J. Survival of virulent and attenuated strains of Brucella abortus in normal and gamma interferon-activated murine peritoneal macrophages. Infect Immun. 1992;60:3011–3014. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.7.3011-3014.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kreutzer D L, Dreyfus L A, Robertson D C. Interaction of polymorphonuclear leukocytes with smooth and rough strains of Brucella abortus. Infect Immun. 1979;23:737–742. doi: 10.1128/iai.23.3.737-742.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liautard J P. Interactions between professional phagocytes and Brucella spp. Microbiologia. 1996;12:197–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martínez de Tejada G, Pizarro-Cerdá J, Moreno E, Moriyón I. The outer membranes of Brucella spp. are resistant to bactericidal cationic peptides. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3054–3061. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.8.3054-3061.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Méresse S, Gorvel J P, Chavrier P. The GTPase rab7 is involved in the transport between late endosomes and lysosomes. J Cell Sci. 1995;108:3349–3358. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108.11.3349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meyer M E. Evolution development and taxonomy of the genus Brucella. In: Adams L G, editor. Advances in brucellosis research. College Station: Texas A & M University Press; 1990. pp. 12–35. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Price R E, Templeton J W, Adams L G. Survival of smooth, rough and transposon mutant strains of Brucella abortus in bovine mammary macrophages. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 1990;26:353–365. doi: 10.1016/0165-2427(90)90119-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rasool O, Freer E, Moreno E, Jarstrand C. Effect of Brucella abortus lipopolysaccharide on oxidative metabolism and lysozyme release by human neutrophils. Infect Immun. 1992;60:1699–1702. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.4.1699-1702.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Riley L K, Robertson D C. Brucellacidal activity of human and bovine polymorphonuclear leukocyte granule extracts against smooth and rough strains of Brucella abortus. Infect Immun. 1984;46:231–236. doi: 10.1128/iai.46.1.231-236.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rojas N, Freer E, Weintraub A, Ramirez M, Lind S, Moreno E. Immunochemical identification of Brucella abortus lipopolysaccharide epitopes. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1994;1:206–213. doi: 10.1128/cdli.1.2.206-213.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seglen P O, Gordon P B. 3-Methyladenine: specific inhibitor of autophagic/lysosomal protein degradation in isolated rat hepatocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79:1889–1892. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.6.1889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schworer C M, Shiffer K A, Mortimore G E. Quantitative relationship between autophagy and proteolysis during graded amino acid deprivation in perfused rat liver. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:7652–7658. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith H, Fitzgeorge R B. The effect of opsonization with antiserum in the survival of Brucella abortus within bovine phagocytes. Br J Exp Pathol. 1964;45:174–180. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smith L D, Ficht T A. Pathogenesis of Brucella. Crit Rev Microbiol. 1990;17:209–230. doi: 10.3109/10408419009105726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sperry J F, Robertson D C. Erythritol catabolism by Brucella abortus. J Bacteriol. 1975;121:619–630. doi: 10.1128/jb.121.2.619-630.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stevens M G, Olsen S C, Pugh G W, Jr, Palmer M V. Immune and pathologic responses in mice infected with Brucella abortus 19, RB51, or 2308. Infect Immun. 1994;62:3206–3212. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.8.3206-3212.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sturgill-Koszycki S, Schlesinger P H, Chakraborty P, Haddix P L, Collins H L, Fok A K, Allen R D, Gluck S L, Heuser J, Russell D G. Lack of acidification in Mycobacterium phagosomes produced by exclusion of the vesicular proton-ATPase. Science. 1994;263:678–681. doi: 10.1126/science.8303277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Swanson M S, Isberg R R. Association of Legionella pneumophila with the macrophage endoplasmic reticulum. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3609–3620. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.9.3609-3620.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Trujillo I Z, Zavala A N, Caceres J G, Miranda C Q. Brucellosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1994;8:225–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]