Abstract

Ninety percent of people with chronic kidney disease (CKD) remain undiagnosed, most people at risk do not receive guideline-concordant testing, and disparities of care and outcomes exist across all stages of the disease. To improve CKD diagnosis and management across primary care, the National Kidney Foundation launched a collective impact (CI) initiative known as Show Me CKDintercept. The initiative was implemented in Missouri, USA from January 2021 to June 2022, using a data strategy, stakeholder engagement and relationship mapping, learning in action working groups (LAWG), and a virtual leadership summit. The Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance framework was used to evaluate success. The initiative united 159 stakeholders from 81 organizations (Reach) to create an urgency for change and engage new CKD champions (Effectiveness). The adoption resulted in 53% of participants committed to advancing the roadmap (Adoption). Short-term results reported success in laying a foundation for CI across Missouri. The long-term success of the CI initiative in addressing the public health burden of kidney disease remains to be determined. The project reported the potential use of a CI initiative to build leadership consensus to drive measurable public health improvements nationwide.

Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) affects an estimated 37 million United States adults with only 10% of patients with stage 3 CKD aware that their kidneys are impaired.1 Chronic kidney disease is defined by the presence of kidney damage or decreased kidney function for 3 or more months.2 Asymptomatic in the early stages, laboratory testing is necessary for diagnosis. To detect CKD, 2 widely available and relatively inexpensive tests are used—serum creatinine with estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (uACR).3,4 The clinical practice guidelines recommend that individuals with diabetes and hypertension receive these tests at least annually.5,6 However, fewer than 20% of people at high risk for CKD receive annual testing.7

In primary care settings, ∼80% of people with laboratory evidence of moderate CKD and nearly 50% of those with advanced CKD do not have the diagnosis documented in their medical records.8 Chronic kidney disease is a disease multiplier, increasing the risk for cardiovascular events and mortality, in addition to progression to end-stage kidney disease (ESKD).9 As CKD advances, morbidity, mortality, and health care utilization increase dramatically.

Although the overarching quality of care is low,7,8,10 communities of color are disproportionately impacted by the disease.1,11 African Americans make up 13% of the US population, but 35% of the US population with kidney failure.12 People who identify as American Indian, Native Hawaiian, Hispanic, and Asian American also have a higher prevalence of kidney disease compared with Whites.12 Driving these disparities are the impacts of structural racism on communities of color, which increase their risk for social determinants of health, such as poverty, food insecurity, and low levels of education that are associated with a higher risk for CKD.13, 14, 15, 16, 17 Centering health equity in kidney health improvement strategies is essential to overcome the racial disparities that exist in CKD.

To address this underrecognized public health burden, the National Kidney Foundation (NKF), Missouri Kidney Program (MoKP), and Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services (MDHSS) partnered to develop a strategy to advance improvements in CKD, called the Show Me CKDintercept Initiative (Show Me CKD). The collective impact (CI) model engages stakeholders from various fields to solve complex social problems that may be challenging to address by one organization alone.18 Given CI’s success in addressing social challenges, it was identified as a potential framework to work across numerous sectors in Missouri to drive the necessary systems and mindset change needed to address rising rates of CKD, low awareness, and late diagnosis.

There are 3 recommended steps or preconditions to begin a CI approach: an influential champion, adequate financial resources, and a sense of urgency for change.19 To create these conditions and develop a common agenda, a data strategy and a wide-reaching summit of stakeholders were used to launch this initiative to improve CKD underdiagnosis in Missouri.

In this paper, we describe the utilization of the CI model, and the application of the Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance (RE-AIM) framework to evaluate the efficacy of the initiative. Our work establishes how the CI model can be used to facilitate improvement in CKD diagnosis and management to enhance population health in Missouri. As gaps in CKD care exist nationwide, the success of this pilot approach will serve as a replicable model for work in other regions.

Patients and Methods

Data Strategy

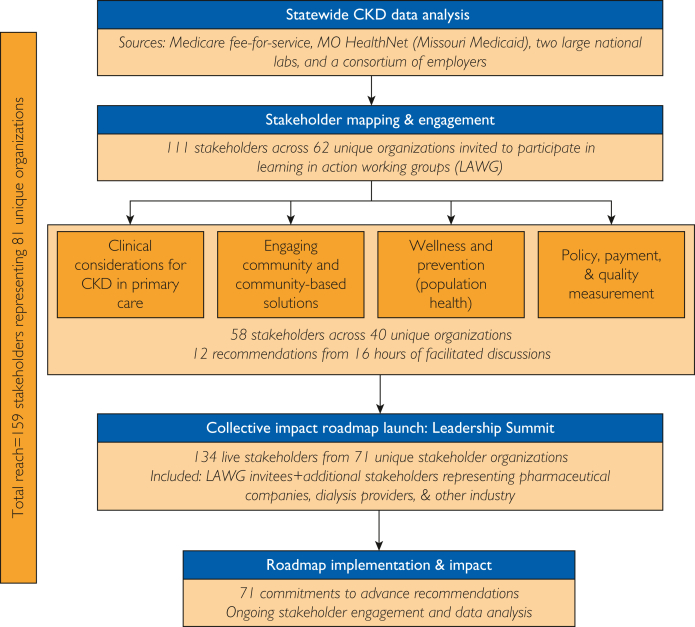

Working in partnership with MoKP, MDHSS, and 2 co-chairs from University Health and the St. Louis Area Business Health Coalition, the NKF used several inputs to create the preconditions for CI (see Figure). First, using CPT codes in claims data, the partners developed a data strategy to expose the low rates of testing and diagnosis in Missouri among people with diabetes or hypertension. Data were obtained from Medicare fee-for-service, MO HealthNet (Missouri Medicaid), 2 large national laboratories, and the St. Louis Area Business Health Coalition, to create a comprehensive picture of the current state of CKD testing in Missouri. This data was used to educate stakeholders on the magnitude of the problem, build collective energy around CKD, and establish a shared understanding of the disease burden.

Figure.

Show Me CKDintercept methods for collective impact—visual depiction. This flow chart displays the key processes used to launch a collective impact (CI) effort in Missouri. Critical steps taken include as follows: (1) Utilization of statewide CKD data to lay a foundational case for action; (2) Engagement of key stakeholders across various sectors for participation in 1 of 4 learning and action working groups (LAWG) titled: Clinical considerations for CKD in primary care, Engaging community and community-based solutions, Wellness and prevention, and Policy, payment, and quality measurement. Of 111 invitations, 58 stakeholders across 40 institutions agreed to participate in a LAWG. Through 16 hours of facilitated discussions the LAWG identified 12 recommended strategies to improve diagnosis and management of CKD in primary care. These recommendations were then used to compose the statewide strategy or roadmap that was launched at the Show Me CKDintercept Leadership Summit (Step 3). Total of 134 stakeholders across 71 organizations attended this live webinar, and 71 of these individuals made commitments to advance 1 or more recommendations. The last step is recommendation implementation where these 71 stakeholders are supporting the execution of strategies. Further stakeholder engagement is being conducted to expand reach and participation, and data is being monitored to measure the impact. To date, 159 individuals from 81 organizations participated in 1 or more steps in the CI process.

Stakeholder Engagement and Relationship Mapping

The partners conducted statewide stakeholder mapping to identify leaders from across the health care and public health sectors who could influence change. Recognizing that cross-sector perspectives can improve collective understanding and mutual accountability for a problem,20 the stakeholders included the following: (1) health care providers and delivery systems; (2) health care payers; (3) public health and other community-based organizations (with specific emphasis on organizations supporting communities facing health disparities); and (4) government and policymakers. Centering equity, efforts were made to understand the population served by each stakeholder to ensure representation of the perspectives of those facing social determinants of health barriers. A total of 111 individuals across 62 organizations were invited to participate in the work, representing various geographies, cultural communities, and types of organizations (public/private/non-profit) to offer diverse perspectives representative of the entire state.

Learning in Action Working Groups

As the power of the CI model arises from enabling collective seeing, learning, and doing,20 the identified stakeholders were invited to participate in 1 of 4 LAWG: Clinical considerations for CKD in primary care, Engaging community and community-based solutions, Wellness and prevention, and Policy, payment, and quality measures. Each LAWG focused on a specific domain (see Figure) and convened 4 times for one hour on a virtual platform to identify barriers, solutions, and implementation strategies within that domain. Facilitators used a structured guide, a virtual whiteboard tool (Miro), polling, and electronic surveys to guide these discussions and generate consensus recommendations. The diffusion of innovation theory was successfully used for reflection and discussion of personal experiences to accelerate barrier identification and recommendation development.21

Virtual Leadership Summit

After distilling the emergent LAWG recommendations, a statewide strategy was launched at the final leadership summit. This 2-hour virtual meeting included a summary of the data strategy, highlighted the LAWG consensus on the nature of the problem, and specific recommendations to drive change with an opportunity for stakeholders to pledge to participate in one or more CI strategies.

Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, And Maintenance Framework

The RE-AIM framework22 was employed to evaluate the combined impact of these approaches on creating the conditions for CI. Both quantitative and qualitative measures were identified (Table 1) across each dimension of RE-AIM.

Table 1.

Show Me CKD RE-AIM Evaluationa

| Dimensionb | Metric | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Reach | Number of working group participants | 58 |

| Number of organizations represented across working groups | 40 | |

| Number of summit attendees (June 9, 2022) | 134 | |

| Number of organizations represented at the summit | 71 | |

| Number of working group participants who participated in the summit | 33 (57%) | |

| Total number of participants engaged in the working groups or summit | 159 | |

| Total number of unique organizations engaged in the working groups or summit | 81 | |

| Description of individual health knowledge (out of 53 summit poll respondents)c: | ||

| who know their blood pressure numbers | 49 (92%) | |

| who know their cholesterol levels | 41 (77%) | |

| who know their eGFR number | 17 (32%) | |

| Types of institutions/sectors (out of 159 summit participants) | ||

| Industry/commercial interests (pharmaceuticals, biotechnology, or dialysis)d | 42 (26%) | |

| Government and publicly funded organizations | 29 (18%) | |

| Health plans and other health care payers | 17 (11%) | |

| Clinicians | 15 (9%) | |

| Health systems | 14 (9%) | |

| Health professional organizations | 13 (8%) | |

| Academia | 12 (8%) | |

| Community organizations | 11 (7%) | |

| Health-related IT | 6 (4%) | |

| Number of unique organizations located in or serving Missouri communities disproportionately impacted by CKDe | 40 (49%) of 81 total organizations | |

| Distribution of rural vs urban stakeholders represented across the state of Missouri (out of 82 summit participants who provided their zip code information)f | ||

| Urban | 76 (93%) | |

| Rural | 6 (7%) | |

| Effectiveness | Number (and percent) of institutions/partners | |

| New/unique partners | 32 (40%) of 81 total organizations | |

| Emerging partners | 5 (6%) of 81 total organizations | |

| Adoption | Number of summit participants who completed a commitment questionnaire to advance at least 1 strategyg | 71 (53%) of 134 summit participants |

| Influential champions | 16 (23%) of 71 summit poll respondents | |

| Engaged CI participant | 27 (38%) of 71 summit poll respondents | |

| Considering CI participation | 25 (35%) of 71 summit poll respondents | |

| Funder | 3 (4%) of 71 summit poll respondents | |

| Number of new/unique and emerging partners who completed a commitment questionnaire to advance at least 1 strategy | 25 (68%) | |

| LAWG participants who completed a commitment questionnaire to advance at least 1 strategy. | 27 (38%) | |

| Number of participants informally supporting implementation of a roadmap strategyh | 9 (13%) | |

| Adopting specific recommendations: | ||

| Number of community partners who have received translated CKD educational resources | 102 | |

| Number of organizations who participated in a local CKD risk campaign | 8 | |

| Number of payers participating in a virtual roundtable series | 10 | |

| Number of partners who have conducted a CKD data analysisi | 8 fully completed and 3 in progress | |

| Number of community pharmacy sites providing CKD risk education and referral to testing | 3 | |

| Number of institutions who have adopted the kidney profile | 3 fully adopted and 1 in progress | |

| Estimated number of patients who will be served by kidney profile adopters and could be impacted by these changesj | 3,80,000 | |

| Number of institutions participating in NKF Learning Collaborative Model | 1 fully adopted and 1 in progress | |

| Implementation | Did we implement all components as intended? | All components were implemented, but the method of delivery changed due to COVID-19. |

| What adaptations were made? | Changed to a virtual format and with a staggered approach- learning in action working groups before final summit, rather than breakout work groups during a 1-d summit. | |

| Did we meet/adhere to collective impact principles/components? | 4 out of 5 CI principles were implemented/met through this process (common agenda, mutually reinforcing activities, shared measurement, and a backbone organization). Only continuous communication remains to be established.k | |

| Time and cost of implementation | Time—18 mo of planning and engagement, through at least bi-weekly meetings; 9 staff + 2 co-chairs on the planning committee; over 300 staff hours; at least $30,000 seed funding to jumpstart the implementation | |

| Maintenance | Proposed measures to include: | As this effort was initiated to evaluate the process associated in generating a common agenda in Missouri, maintenance was excluded from our analysis. Some suggested measures were identified. |

| Number of stakeholders engaged in the initiative >1 y | ||

| Number of recommendations that get implemented after 1, 2, and 5 y. | ||

| Ongoing engagement of committed stakeholders | ||

| Long term—changes in rates of CKD testing in Missouri. Comparison of rates or increases in Missouri vs other states without a CI initiative. | ||

Abbreviation: CKD, chronic kidney disease; CI, collective impact; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; LAWG, learning in action working groups; IT, information technology; NKF, National Kidney Foundation; RE-AIM, reach effectiveness-adoption implementation and maintenance; Show Me CKD, Show Me CKDintercept initiative.

RE-AIM dimensions were defined in reference to Glasgow RE, Harden SM, Gaglio B, et al. RE-AIM planning and evaluation framework: adapting to new science and practice with a 20-year review. Frontiers in Public Health. 2019;7: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2019.00064.

Poll of Missouri Leadership Summit attendees to understand the gap in knowledge of BP and cholesterol numeracy vs eGFR (kidney function) numeracy. Multiple choice response options for each question were Yes or No.

Industry members were only invited to participate in the final summit, to avoid conflict of interest in developing the recommendations.

Communities disproportionately impacted by CKD defined as African American, American Indian, Native Hawaiian, Hispanic, and Asian American communities with increased risk for social determinants of health, such as poverty, food insecurity, and low levels of education. Organization or its service region located in a census tract with a CDC/ATSDR Social Vulnerability Index in the top 75th percentile. Adapted from the Missouri Hospital Association health equity interactive dashboard: https://web.mhanet.com/health-equity-dashboards-step- 5/#social.

Source- Health Resources Service Administration (HRSA) defines the following areas as rural: all non-metro counties, all metro census tracts with RUCA codes 4-10 and large area Metro census tracts of at least 400 sq. miles in area with population density of 35 or less per sq. mile with RUCA codes 2-3. Beginning with Fiscal Year 2022 Rural Health Grants, we consider all outlying metro counties without a UA to be rural.

Categorized levels of support: Influential Champions: willing to serve as a chair or leader on a project, or willing to be a connector or convener to bring new participants to the initiative; Engaged CI participant: committed to work on a project or task force related to the CI initiative; Prospective CI participant: able to help minimally or did not specify a level of commitment; or Funder: willing to provide funding to support to one or more initiatives.

Informal commitment was defined as individuals who have participated in a recommendation related activity post leadership summit but did not complete a commitment form at the Summit.

Data partners include health plans, health systems, and FQHCs, 3 partners amid a CKD data pull.

The estimated impact of the kidney profile was calculated from analysis of community health needs assessment reports and publicly available data on the number of outpatient visits, patients per institution, and the state-level CDC population prevalence data and patient encounter data provided by the Missouri Hospital Association.

CI principles implemented: 1) common agenda—the knowledge and mindset change resulting from the LAWG and final summit focused all partners on specific targets—primarily the importance of earlier testing and more upstream interventions to address CKD; 2) mutually reinforcing activities—the LAWG discussions generated a series of 12 consensus recommendations with specific activities that partners can advance on their own or as part of working groups or task forces; 3) shared measurement—while the exact measures of success are yet to be determined, the recommendations developed included recommendations related to measurement and data collection which will help ensure that measurement is a component of a future CI initiative; 4) a backbone organization. In laying the pre- conditions for change, NKF leadership recognized the value and impact of this work as well as the need to serve in the backbone role for a sustainable initiative.

Results

The RE-AIM domains and definitions, the specific metrics identified to evaluate the impact of using a data driven LAWG strategy to build a common agenda, and the outcomes for each metric are included in Table 1.

Reach

Of the 111 stakeholders invited, 58 stakeholders from 40 Missouri institutions accepted the invitation to participate in a LAWG. The LAWG resulted in robust discussions regarding the quality of CKD care in Missouri, leading to 12 recommendations, under 5 common themes summarized in Table 2. These recommendations are referred to as the Missouri roadmap and serve as the common agenda for the CI initiative. The summit engaged 134 individuals, representing 71 institutions. In total, as described in the Supplemental Appendix (available online at http://www.mcpiqojournal.org), 159 unique stakeholders representing 81 organizations were reached through either the LAWG discussions, summit, or both.

Table 2.

Show Me CKD Roadmap Implementationa

| Improve Public Awareness of CKD | ||

|---|---|---|

| LAWG Recommendation | Description of Action | Current Status |

| Catalog community programs and partners in Missourib,c,d,e | Build a database of community-facing chronic disease programs where additional training or materials regarding CKD may be provided. Build connections and improve linkages among partners who are providing services to address social determinants of health. |

Status: Not yet started |

| Inform CHW or frontline worker engagement strategyb,e | Provide tools, resources, and training for CHW to engage people at risk for or living with CKD to improve CKD testing and diagnosis. | Status: After key informant interviews and a CHW workshop at NKF’s spring clinical meetings, NKF developed a CHW educational video series and is in the process of launching additional modules with the support of CHW committee members across Missouri and in partnership with national CHW leaders. The NKF’s CHW hub will feature specific trainings with a certificate of completion available for learners and tools to engage patients in CKD awareness, detection, and management. |

| Localize CKD awareness and educational tools to meet the needs of individual communitiesb | Collaborate with local partners to directly engage with those disproportionately burdened by kidney disease to increase resource utilization, understanding, and patient engagement. | Status: NKF and MoKP collaborated with local partners to engage community members at risk for CKD (with diabetes or hypertension) in understanding the most effective content, delivery, and dissemination strategies for the NKF risk quiz and accompanying resources. This community engagement process took place in August 2023 and September 2023 with 3 focus group discussions targeting low-income/Medicaid eligible and Hispanic participants across the St. Louis Promise Zone region and rural participants in Randolph County. After analysis of the focus group conclusions, minor recommended changes will be made as necessary to the campaign materials to increase resource engagement, CKD understanding, and patient activation, especially among this at-risk population (diabetes and/or hypertension) impacted by CKD. The report’s findings will also be leveraged in tailoring communication and effectively reaching communities across Missouri. The NKF is exploring local funding opportunities to expand this public awareness strategy in tracking patient activation from the risk quiz and campaign materials. |

| Clinician, Health System, & Payer Opportunities | ||

|---|---|---|

| LAWG Recommendation | Description of Action | Current Status |

| Prioritize KED HEDIS Measuref | Survey health plans to understand current practices and prioritization of KED HEDIS measure. Convene payers to provide education on the value of the KED HEDIS measure. Explore strategies to increase the number of payers prioritizing this measure. |

Status: Implementation was in conjunction with the payer roundtable strategy. |

| Implement the kidney profile in health systems and local laboratoriese,g | Recognize the value of the Kidney Profile as a tool to streamline ordering of CKD tests Increase the number of institutions with independent labs to implement the Kidney Profile. |

Status: Since engagement for Show Me CKD began, 3 large institutions have fully implemented and 1 has begun implementing the kidney profile. The resources to assist in implementation were provided to all participants who identified this strategy on their commitment forms. Next steps include convening kidney profile implementers to discuss data outcomes, lessons learned, and opportunities to increase uptake with optimizing clinical decision support tools. |

| Participate in or promote kidney disease ECHOe,h | Increase CKD knowledge and provide educational resources to primary care clinicians. Increase participation at the show-me kidney disease ECHO series. |

Status: Information about the show-me kidney disease ECHO series has been disseminated electronically on a quarterly basis to all participants who identified this strategy in their commitment forms. It has also been promoted at grand rounds presentations to encourage participation across Kansas City University, Saint Louis University, and University of Missouri system and at the CKD learning collaborative practice meetings. |

| Participate in an NKF CKD Learning Collaborativee | Expand NKF's CKD Learning Collaborative to engage more health systems and primary care clinicians in an active process of change. | Status: NKF is currently working with University Health to implement a CKD Learning Collaborative. Three pilot clinics were onboarded in February 2023, with plans to eventually expand across University Health’s 9 ambulatory care practices. Teams will review performance data on an ongoing basis. The NKF continues to meet with interested institutions to explore next steps for implementation of a future learning collaborative. One additional institution is in the final stages of signing an MOU to begin a learning collaborative. |

| Convene Strategic Partners | ||

|---|---|---|

| LAWG Recommendation | Description of Action | Current Status |

| Payer roundtablee,f | Convene a Missouri payer roundtable to explore strategies to prioritize the KED HEDIS measure and other quality measures to improve CKD outcomes. | Status: The NKF held a series of virtual learning in action meetings to bring together 10 senior leaders from health plans and other payers across Missouri. Beyond prioritization of the KED HEDIS measure, attendees voiced interest in deploying a provider and member shared campaign strategy around increased attention for CKD testing and diagnosis in primary care, which in turn will support providers and health systems in meeting these quality outcomes. The NKF is currently meeting individually with these organizations to advance this collaborative program. Most discussions have focused on the importance of beginning with CKD data analysis to understand gaps in care and opportunities for improvement. A payer follow-up meeting will be held in November 2023 to discuss next steps associated with execution of a shared strategy. |

| Chronic disease conference or conveningb,c,d,e,f,g,h | Develop a cohesive strategy around chronic disease improvement targets to focus the impact of improvement initiatives and reduce burden in primary care. Convene payers, clinicians, and community organizations to discuss collaborative strategies, shared tools, and cohesive messaging. |

Status: Not yet started |

| Create a CKD Dashboard for Missouri | ||

|---|---|---|

| LAWG Recommendation | Description of Action | Current Status |

| Participate in CKD data dashboard workgroupb,c,e,f,h | Create a Missouri “report card” to measure rates of CKD testing and management accurately and comprehensively. Establish a work group to identify and recruit data sources for the dashboard. Determine key metrics to report, frequency of reporting, and other logistics. Identify partners to host the dashboard, conduct analysis, etc. |

Status: Preliminary work has begun by the leadership of MoKP to display all stages of kidney disease and to highlight areas of opportunity in the state. Next steps include development of national data dashboard in summer 2024 and exploration of leveraging local longitudinal data from early CKD to ESKD with concrete calls to action and areas of opportunity. |

| Review your own institution’s CKD datae,f,g,h | Analyze CKD testing and management data to reflect the landscape of CKD underdiagnosis and monitor progress in the state of Missouri. | Status: Eight NKF partners, such as health plans, health systems, and FQHCs, have conducted a CKD data analysis with 3 partners amid a CKD data pull. The NKF continues to meet with interested stakeholders to share data pull and analysis tools. |

| Explore Novel Approach Approaches to CKD Testing | ||

|---|---|---|

| LAWG Recommendation | Description of Action | Current Status |

| Participate in a pilot project or otherwise support novel approaches to CKD testing in pharmaciesb,h,i,j | Engage pharmacists and CHWs in novel approaches for improved CKD testing. | Status: The NKF and the CPESN MO received funding from the Missouri foundation for health to study the feasibility and impact of pharmacy-driven testing for people living with CKD. Implementation began in February 2023. Over a 24-mo intervention, 3 community-based pharmacy sites in Missouri will provide CKD risk education and referral to testing. The outcomes of this pilot will be used to advocate for expanded authority for pharmacists in Missouri to provide better care for at-risk patients and increase access to care for underserved communities. As mentioned above, we will continue to disseminate an evolving CHW toolkit across Missouri. There will be future exploration of opportunities to pilot test and evaluate interventions that use CHWs to improve CKD testing. |

Abbreviation: CHW, community health worker; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CPESN MO, Community Pharmacy Enhanced Services Network of Missouri; ECHO, Extension for Community Health Care Outcomes; ESKD, end-stage kidney disease; FQHC, federally qualified health center; HEDIS, health care effectiveness data and information set; KED, kidney health evaluation for patients with diabetes; LAWG, learning in action working groups; MOU, memorandum of understanding; MoKP, Missouri Kidney Program; NKF, National Kidney Foundation; Show Me CKD, Show Me CKDintercept initiative.

Community organizations and Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHC).

Government and publicly funded organizations.

Health professional organizations.

Health system.

Health plans and health care payers.

Academic medical centers.

Clinicians.

Pharmacies.

Laboratories.

Effectiveness

The primary goals were to build consensus on the unrecognized burden of CKD in Missouri (generate urgency for change), activate leaders in health care and public health to engage in strategies to drive changes in early diagnosis of CKD in primary care (develop influential champions), and identify partners to financially support the efforts (adequate financial resources). The LAWG were the catalyst for building consensus among a broader group of summit attendees who were consequently inspired to align with NKF and other partners on this initiative. Overall, 32 (40%) new partners, defined as institutions or individuals who had not previously engaged with NKF, participated in the initiative. Another 5 institutions were classified as emerging partners (6%), defined as organizations that had engaged in some initial meetings or discussions but had never actively partnered with NKF on a program or activity in the state. One important report of the effectiveness of this program was the impact the data story created to facilitate awareness and engagement (urgency for change). This impact is specifically reflected in the LAWG recommendation for creating a state-level dashboard to measure longitudinal change in CKD testing and diagnosis across Missouri.

Adoption

Seventy-one stakeholders (53%) made commitments to support 1 or more recommendations at varying levels of support categorized in Table 1. Even in the initial stages of the roadmap implementation, partners are already advancing strategies. Four institutions have taken concrete steps toward the adoption of the kidney profile (laboratory test) in their institutions, 3 of which have fully implemented it since beginning to engage with the CI partners. One integrated health system is implementing NKF’s CKD Learning Collaborative, an activity to evaluate and improve CKD quality of care in primary care. In addition, 3 institutions are now engaged with NKF in a funded research program to evaluate the feasibility and impact of pharmacy-driven CKD testing in Missouri.

Implementation

Implementation of this foundational CI strategy required significant resources, primarily human capital, to execute as designed. A planning team of 9 individuals from NKF and MoKP met bi-weekly for approximately 18 months to design and execute the strategy. The data strategy alone required about 35 hours of analyst time from each data partner to create a comprehensive data story. In addition, the work engaged 2 co-chairs in bi-monthly meetings to support strategy design and stakeholder mapping. Grant funding by MDHSS and MoKP, provided the initial funding to support the NKF staff time required to execute the CI strategy. Each LAWG used 2 volunteer co-facilitators, in addition to at least 2 planning team members to execute each virtual meeting, build agendas, compile notes, and facilitate the consensus-building process. Each meeting required at least 2 hours of preparation and follow-up from planning committee staff, representing a total of 12 hours per working group (48 hours total for the 4 LAWG).

The utilization of stakeholders as facilitators of the LAWG ensured that the discussions were organic and did not reflect any bias from the backbone organization. During the final summit, members of the LAWG presented their recommendations furthering the momentum of the CI common agenda and engagement of other parties.

Maintenance

Although measures for the maintenance dimension were identified, this measurement is excluded from this preliminary phase of the evaluation because of the short amount of time after the initial roadmap implementation.

Discussion

Our experiences in the developmental phase of the CKD CI initiative have led to several best process recommendations. We successfully met all 3 preconditions for CI and reported a replicable process for building a consensus-based, state-level common agenda. Stakeholder recruitment meetings, LAWG, and the summit all served as mechanisms to increase awareness of gaps in CKD diagnosis, and the impact of CKD in the state. These discussions resulted in a decision to act among both new and existing partners (urgency for change). This CI principle was further justified by the 53% of summit attendees who committed to supporting at least 1 recommendation. Of importance, nearly half of the committed stakeholders were new or emerging partners to NKF demonstrating Show Me CKD’s success in bringing new stakeholders from disparate fields to address the problem. As only 38% of the adopters participated in both a LAWG and the summit, we found that one-time summit participation can lead to commitment. However, of the 23% of adopters who expressed interest in leading a recommendation, the majority were LAWG participants suggesting multiple engagements increase dedication to the CI effort. Finally, the initiative served as a mechanism to identify and engage additional funders to support the ongoing CI work, as evidenced by grant funding generated throughout the developmental phase and in the months since the summit.

Besides achieving the preconditions, this approach established and laid the foundation for 4 of the 5 core components required for successful CI implementation (see Table 3). Although Show Me CKD is still nascent, progress has been made in maintaining the sense of urgency, engaging partners, and advancing the mutually reinforcing activities that arose from this developmental phase. The NKF has added a population health manager and CI director in Missouri to support its efforts as the backbone organization. A strategy for ongoing formative (evaluation of the effectiveness of the backbone organization in maintaining momentum and engagement) and summative (assessment of the impact these activities will have on CKD screening or diagnosis rates, rates of CKD progression, or cardiovascular impacts of CKD in the state) evaluation is being employed to develop shared measurement and provide continuous feedback to the community regarding this initiative. The model is also scalable. After Missouri’s success, the NKF implemented a similar effort in Virginia and Washington DC, engaging another 150 stakeholders in the creation and launch of a roadmap. Efforts are currently underway to bring the CI strategy to 8 additional states.

Table 3.

Defining the Components of Collective Impacta

| The Five Conditions of Collective Impactb | Show Me CKD Result | |

|---|---|---|

| Common agenda | All participants have a shared vision for change, including a common understanding of the problem and a joint approach to solving it through agreed on actions. | Improve CKD awareness, testing, and management in Missouri, especially in communities disproportionately burdened by CKD. |

| Shared measurement | Collecting data and measuring results consistently across all participants ensures efforts remain aligned and participants hold each other accountable. | Not yet available, planned implementation in summer 2024 through a national dashboard. Metrics to measure: rates of CKD testing, CKD incidence and prevalence, CKD progression, or cardiovascular impacts of CKD in the state |

| Mutually reinforcing Activities | Participant activities must be differentiated while still being coordinated through a mutually reinforcing plan of action. | 12 recommendations (the roadmap) |

| Continuous communication | Consistent and open communication is needed across the many stakeholders to build trust, assure mutual objectives, and appreciate common motivation. | Multiple avenues of communication include webpage, quarterly newsletter, follow-up meetings, and ongoing networking |

| Backbone support | Creating and managing collective impact requires a dedicated staff and a specific set of skills to serve as the backbone for the entire initiative and coordinate participating organizations and agencies. | NKF–dedicated staff (population health partnership manager and collective impact director) (webpage, Zoom platform for meetings, etc) |

Abbreviations: CKD, chronic kidney disease; NKF, National Kidney Foundation; Show Me CKD, Show Me CKDintercept initiative.

Adapted from: Tamarack Institute. TOOL|five conditions of collective impact. Accessed January 28, 2023. https://www.tamarackcommunity.ca/hubfs/Collective%20Impact/Tools/Five%20Conditions%20Tools%20April%202017.pdf.

Several lessons for the implementation of CI can be garnered from this experience. Show Me CKD demonstrated that significant human resources are required to build a successful CI initiative. In addition to the time, the effort required a planning team and co-chairs with sufficient social capital to bring stakeholders to the table to participate in these discussions. The data strategy was especially labor intensive and required commitment from 5 partners who contributed analyst time to conduct each data pull. Financial resources were also required for the planning, preparation, and summit execution; without foundational funding from MDHSS and MoKP to launch the effort, NKF may not have been able to dedicate the necessary time needed for this project. Beyond these grants, planning time exceeded the staff time covered by grant funds; however, early buy-in from organizational leadership allowed staff the flexibility to allocate additional time to focus on this effort, illustrating the importance of organizational support on the front end of establishing a CI effort. As the roadmap moved on to implementation, the need for dedicated staff was identified, in addition to ongoing funding to ensure that momentum is maintained. Without these resources, Show Me CKD could have languished after the completion of the leadership summit. Backbone and participating organizations need leadership support and buy-in for sustainment.

In laying the foundation for CI, a collaborative effort is needed for success. The participation of multiple organizations, team members in different geographic areas, and well-connected co-chairs was essential for the effective engagement of a diverse group of stakeholders. Having the appropriate partners in place to use the data to drive culture change and credible results contributed to the success. Moreover, the diversity of perspectives from these stakeholders in the LAWG was integral in creating a comprehensive set of recommendations and contributing to robust engagement during the final summit. Earlier efforts, including a 2008 Missouri Chronic Kidney Disease Task Force, may have also contributed to the statewide success providing preliminary awareness and recommendations.23

Our experience also illustrates the limitations associated with building a comprehensive statewide initiative. Despite efforts to engage stakeholders in all areas, representation from rural communities and communities of color was limited, similar to challenges of other CI initiatives.24 Hence, CI implementation in a more rural state may not be informed by this deployment. Ongoing outreach will be needed during the implementation phase to build broader representation and ensure that solutions have an equitable impact. Despite attempts to reach some previously committed stakeholders, ongoing engagement remains challenging. Future work should explore reasons for noncommitment and strategies to sustain engagement.

The public health implications of our work could be significant. As noted earlier, CKD remains an underrecognized public health burden, impacting nearly 700,000 in Missouri alone.1 Although the prevalence of CKD is similar to the prevalence of diabetes, and causes more deaths than breast or prostate cancer, it receives less public recognition and public health funding.25, 26, 27 Just as influential advocates increased knowledge, public concern, and funding for breast cancer, the successful implementation of a CI initiative and increased engagement of influential champions could profoundly impact the trajectory of awareness and investment in CKD over the coming years.28

Timely diagnosis of CKD and utilization of guideline-concordant interventions can slow CKD progression, reduce rates of ESKD, and lessen the cardiovascular impact.29 The advent of new therapeutics in recent years offers additional opportunities for health improvement, particularly cardiovascular risk reduction.30 Successful implementation of the roadmap could drive improvements in rates of testing, early diagnosis, and access to treatment. In turn, these outcomes could facilitate the scaling of successful population health strategies to improve CKD outcomes nationwide.

Our experience adds to the body of research demonstrating the utility of CI, specifically in increasing awareness and momentum for underrecognized public health challenges. In a cross-study of 25 CI initiatives, 20 sites reported sustained improvements in health or social outcomes after at least 8 years of sustained maintenance.31 Most CI efforts require time to develop a solid foundation for long-term success.32,33 A CI initiative to reduce and prevent childhood obesity required 5 years to contribute to a 3.7% decrease in childhood obesity rates in San Diego County.34 As Show Me CKD is positioned to address chronic disease inequities with ongoing commitment of resources and time, we anticipate improvements in appropriate testing and diagnosis. Additional time will allow for outcome analysis to demonstrate whether the CI changes will be maintained, and the sustained uptake and engagement of stakeholders will be an area of future study. Furthermore, there is potential to illustrate the extent to which this approach will impact CKD outcomes in the state and the impact on health care costs.

Efforts to improve early diagnosis of CKD are not new;23,35 however, this represents the first time, to our knowledge, that a CKD initiative has leveraged the CI model. We have reported the use of CI to unite a large volume of stakeholders to support population health improvement strategies for CKD. Because this is a novel approach beginning in Missouri, there are opportunities to compare how outcomes in Missouri change relative to other states that have not implemented a similar strategy.

Potential Competing Interests

We have communicated with all co-authors and obtained their full disclosures with no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The leadership summit work was funded by the Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services, through CDC 1817 Grant. The Missouri Kidney Program funded the planning and preparation. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Footnotes

Supplemental material can be found online at http://www.mcpiqojournal.org. Supplemental material attached to journal articles has not been edited, and the authors take responsibility for the accuracy of all data.

Supplemental Online Material

References

- 1.Chronic Kidney Disease in the United States. United States Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilson S., Mone P., Jankauskas S.S., Gambardella J., Santulli G. Chronic kidney disease: definition, updated epidemiology, staging, and mechanisms of increased cardiovascular risk. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2021;23(4):831–834. doi: 10.1111/jch.14186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoerger T.J., Wittenborn J.S., Segel J.E., et al. A health policy model of CKD: 2. The cost-effectiveness of microalbuminuria screening. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;55(3):463–473. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Komenda P., Ferguson T.W., Macdonald K., et al. Cost-effectiveness of primary screening for CKD: a systematic review. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;63(5):789–797. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee Addendum. 11. Chronic Kidney Disease and Risk Management: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2022. Diabetes Care. 2022;45(Suppl. 1) doi: 10.2337/dc22-ad08a. S175-S184. Diabetes Care. 2022;45(9):2182-2184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group KDIGO 2012 Clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl. 2013;3(1):136–150. doi: 10.1038/kisup.2012.72. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alfego D., Ennis J., Gillespie B., et al. Chronic kidney disease testing among at-risk adults in the U.S. remains low: real-world evidence from a national laboratory database. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(9):2025–2032. doi: 10.2337/dc21-0723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Szczech L.A., Stewart R.C., Su H.L., et al. Primary care detection of chronic kidney disease in adults with type-2 diabetes: the ADD-CKD study (awareness, detection and drug therapy in type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease) PLoS One. 2014;9(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vassalotti J.A., DeVinney R., Lukasik S., et al. CKD quality improvement intervention with PCMH integration: health plan results. Am J Manag Care. 2019;25(11):e326–e333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tummalapalli S.L., Powe N.R., Keyhani S. Trends in quality of care for patients with CKD in the United States. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019 August 7;14(8):1142–1150. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00060119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Chronic Kidney Disease Fact Sheet. United States Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saran R., Robinson B., Abbott K.C., et al. US Renal Data System 2016 Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of Kidney disease in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016;69(3 Suppl1):A7–A8. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crews D.C., Charles R.F., Evans M.K., Zonderman A.B., Powe N.R. Poverty, race, and CKD in a racially and socioeconomically diverse urban population. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;55(6):992–1000. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crews D.C., McClellan W.M., Shoham D.A., et al. Low income and albuminuria among REGARDS (reasons for geographic and racial differences in stroke) study participants. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;60(5):779–786. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bruce M.A., Beech B.M., Crook E.D., et al. Association of socioeconomic status and CKD among African Americans: the Jackson Heart study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;55(6):1001–1008. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crews D.C., Kuczmarski M.F., Grubbs V., et al. Effect of food insecurity on chronic kidney disease in lower-income Americans. Am J Nephrol. 2014;39(1):27–35. doi: 10.1159/000357595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Borrell L.N., Elhawary J.R., Fuentes-Afflick E., et al. Race and genetic ancestry in medicine – a time for reckoning with racism. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(5):474–480. doi: 10.1056/NEJMms2029562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kania J., Kramer M. Collective impact. Stanford Soc Innov Rev. 2011;9(1):36–41. doi: 10.48558/5900-KN19. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hanleybrown F., Kania J., Kramer M. Channeling change: making collective impact work. Stanford Soc Innov Rev. 2012 doi: 10.48558/2T4M-ZR69. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hanleybrown F., Juster J.S., Kania J. Essential mindset shifts for collective impact. Stanford Soc Innov Rev. 2014;12(4):A2–A5. doi: 10.48558/VV1R-C414. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rogers E.M. 5th ed. Free Press; 2003. Diffusion of Innovations. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Glasgow R.E., Vogt T.M., Boles S.M. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(9):1322–1327. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services Missouri Chronic Kidney Disease Task Force Report and Recommendations to the Missouri General Assembly. http://mokp.missouri.edu/MOKP/docs/CKDtaskforceRpt.pdf Missouri Kidney Program; published 2008 Oct.

- 24.Riley C., Roy B., Lam V., et al. Can a collective-impact initiative improve well-being in three US communities? findings from a prospective repeated cross-sectional study. BMJ, (Open) 2021;11(12) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-048378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Diabetes Statistics Report Website. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/data/statistics-report/index.html

- 26.Murphy S.L., Xu J.Q., Kochanek K.D., Arias E., Tejada-Vera B. Deaths: final data for 2018. Natl Vital Stat Rep. National Center for Health Statistics. 2021;69(13):1–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mendu M.L., Erickson K.F., Hostetter T.H., et al. Federal funding for kidney disease research: a missed opportunity. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(3):406–407. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.303009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Osuch J.R., Silk K., Price C., et al. A historical perspective on breast cancer activism in the United States: from education and support to partnership in scientific research. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2012;21(3):355–362. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2011.2862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bullock A., Burrows N.R., Narva A.S., et al. Vital Signs: Decrease in Incidence of Diabetes-Related End-Stage Renal Disease among American Indians/Alaska Natives – United States, 1996-2013. Vital Signs. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(1):26–32. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6601e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mottl A.K., Alicic R., Argyropoulos C., et al. KDOQI US commentary on the KDIGO 2020 clinical practice guideline for diabetes management in CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2022;79(4):457–479. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2021.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.When collective impact has impact: a cross-site study of 25 collective impact initiative. ORS impact. https://www.orsimpact.com/DirectoryAttachments/10262018_111513_477_CI_Study_Report_10-26-2018.pdf

- 32.Meinen A., Hilgendorf A., Korth A.L., et al. The Wisconsin early childhood obesity prevention initiative: an example of statewide collective impact. WMJ. 2016;115(5):269–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Flood J., Minkler M., Hennessey Lavery S., Estrada J., Falbe J. The collective impact model and its potential for health promotion: overview and case study of a healthy retail initiative in San Francisco. Health Educ Behav. 2015;42(5):654–668. doi: 10.1177/1090198115577372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Our Impact San Diego county childhood obesity initiative. https://sdcoi.org/our-impact/#:∼:text=From%202005%2D2010%2C%20the%20collective,many%20California%20counties%20saw%20increases

- 35.North Carolina Institute of Medicine . North Carolina Med J; 2012. Task force on chronic kidney disease: addressing chronic kidney disease in North Carolina.https://nciom.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/CKD-Update-Final-11-5-2012.pdf [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.