Abstract

Introduction

Immune checkpoint inhibition (ICI) has improved patients’ outcomes in advanced melanoma, often resulting in durable response. However, not all patients have durable responses and the patients with dissociated response are a valuable subgroup to identify mechanisms of ICI resistance.

Methods

Stage IV melanoma patients treated with ICI and dissociated response were retrospectively screened for available samples containing sufficient tumor at least at two time-points. Included were one patient with metachronous regressive and progressive lesions at the same site, two patients with regressive and novel lesion at different sites, and three patients with regressive and progressive lesions at different sites. In addition, four patients with acquired resistant tumor samples without a matched second sample were included.

Results

In the majority of patients, the progressive tumor lesion contained higher CD8+ T cell counts/mm2 and interferon-gamma (IFNγ) signature level, but similar tumor PD-L1 expression. The tumor mutational burden levels were in 2 out 3 lesions higher compared to the corresponding regressive tumors lesion.

In the acquired tumor lesions, high CD8+/mm2 and relatively high IFNγ signature levels were observed. In one patient in both the B2M and PTEN gene a stop gaining mutation and in another patient a pathogenic POLE mutation were found.

Conclusion

Intrapatient comparison of progressive versus regressive lesions indicates no defect in tumor T cell infiltration, and in general no tumor immune exclusion were observed.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00262-023-03581-6.

Keywords: Melanoma, Immune checkpoint inhibition, Dissociated response, Acquired resistance

Introduction

Immune checkpoint inhibition (ICI) has shown improvement in overall survival (OS) in a broad range of advanced malignancies and has become a standard treatment option, amongst others, for stage IV melanoma patients [1–7]. In a subset of patients treated with ICI durable responses are seen, which can persist after (early) treatment discontinuation [8, 9] and result in a plateau of 36% for anti-CTLA-4 plus anti-PD-1 combination and 8–29% for anti-PD-1 monotherapy [2].

There are, however, also dissociated response patterns [10]. For instance, mixed response, with some tumor lesions regressing while other persist or increase in size, and acquired resistance, when a tumor lesion initially responds or stays stable for long periods of time, but eventually progression is observed [10, 11]. These heterogeneous clinical patterns of response can be both spatial, with different responses in different tumor lesions as in mixed response, and temporal, with different responses over time [11]. There are different resistant mechanisms to ICI proposed [12]. Innate resistance is defined as initial non-responding tumor lesions to ICI. If a tumor is recognized by the immune system, but it is also capable of adapting and thereby escaping the immune attack, it is termed acquired resistance. Since tumor lesions are constantly evolving, this could either result in innate resistance, mixed response or acquired resistance [12].

The biological mechanisms underlying dissociated response are still being explored. Resistance to ICI can manifest at different times, but in many cases similar or overlapping mechanisms contribute to the immune escape from tumor cells [12]. Acquired resistance can be the result of, e.g., changes in the tumor neoantigen presentation machinery. Due to a selection of non-responsive clones or to mutations resulting in loss of neoantigen, tumor antigen presentation is downregulated, causing a lack of T cell recognition [11, 13]. Alterations in genes encoding for components needed for antigen processing and/or presentation can lead to ICI resistance as well [11]. Other factors, such as an immune suppressive tumor microenvironment and DNA mismatch repair deficiencies, can play a role in resistance mechanisms as well [14]. Understanding of these mechanisms by comparison of paired biopsy samples may guide rational design of salvage therapies or preventive strategies.

In this study, we aimed to assess histopathological, DNA and RNA characteristics of paired biopsies of regressive and progressive tumor lesions, in an effort to gain insight in mechanisms of dissociated response to ICI in a cohort of stage IV melanoma patients.

Methods

Patient and material selection

Patients with stage IV melanoma treated in the Netherlands Cancer Institute between 2010 till May 2019 with dissociated response patterns (defined as both regressive and progressive tumor lesions present on CT evaluation scans) to ICI treatment were screened for availability of tumor material. ICI treatment consisted of either pembrolizumab (anti-PD-1 mAb) 2 mg/kg or in a fixed dose of 150–200 mg intravenously every three weeks, nivolumab (anti-PD-1 mAb) 3 mg/kg or in a fixed dose of 240 mg intravenously every three weeks, ipilimumab (anti-CTLA-4mAb) 3 mg/kg every three weeks for a maximum of four cycles, or ipilimumab 1 mg/kg plus nivolumab 1 mg/kg for four cycles followed by maintenance nivolumab 240 mg every three weeks.

Patients with dissociated response, who did not opt out for use of remaining tumor material for research purpose or had given informed consent for performing additional biopsies for research purposes, were screened for availability of tumor samples. When both a regressive baseline tumor sample (taken within 3 months before start treatment) and a tumor sample of a progressive lesion with sufficient tumor cells (at least 30% tumor cells of HE stained frozen section) were present, patients were included.

Clinical characteristics and RECIST response were collected from patient records. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki after approval by the local institutional review board.

Immunohistochemistry

The formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples were stained for both PD-L1 and CD8. Immunohistochemistry of the FFPE tumor samples was performed on a BenchMark Ultra autostainer (Ventana Medical Systems). Briefly, paraffin sections were cut at 3 µm, heated at 75 °C for 28 min and deparaffinized in the instrument with EZ prep solution (Ventana Medical Systems). Heat-induced antigen retrieval was carried out using Cell Conditioning 1 (CC1, Ventana Medical Systems) for 32 min at 95 °C (CD8) or 48 min at 95 °C (PD-L1). CD8 was detected using clone C8/144B (1/100 dilution, 32 min at 37 °C, Agilent/DAKO) and PD-L1 was detected using clone 22C3 (1/40 dilution, 1 h at RT, Agilent/DAKO). Bound antibody was detected using the OptiView DAB Detection Kit (Ventana Medical Systems). Slides were counterstained with Hematoxylin and Bluing Reagent (Ventana Medical Systems). A Pannoramic® 1000 scanner from 3DHISTECH was used to scan the slides at a 40 × magnification. The stained FFPE slides were scored by a blinded pathologist using Slidescore (www.slidescore.com). Of each biopsy, five representative areas of 0.2mm2 were selected to assess the number of CD8+ cells/mm2.

RNA and DNA sequencing

RNA and DNA were simultaneously isolated from FFPE sections (10 µm) with the AllPrep DNA/RNA FFPE kit (Qiagen, 80,234), according to manufacturers’ protocol, using the QIAcube. Non-tumor DNA to determine mutation load, was isolated from PBMCs using the AllPrep DNA/RNA FF kit (Qiagen, 80,224), and when no PBMCs were available, from whole blood samples, using the MagNa Pure Compact Nucleic Acid Isolation Kit.

Transcriptome and whole-exome sequencing were performed by CeGaT GmbH (Tübingen, Germany). Transcriptome libraries were generated using the KAPA RNA HyperPrep with RiboErase (HMR) & SMART-Seq stranded total RNA (Takara). Exome libraries were generated using the Twist Human Core Exome Plus (Twist Bioscience). These libraries were sequenced with 2 × 100 base pair reads on a NovaSeq 600 system according to manufacturer’s protocols, with a sequence quality value of > 93% for transcriptome and > 90% for exome libraries.

Data were analyzed in the CeGaT analysis pipeline. Briefly, demultiplexing of the sequencing reads was performed with Illumina bcl2fastq (2.20) and adapters trimmed with Skewer (v0.2.2) [15]. The quality of FASTQ files was analyzed with FastQC (v0.11.5-cegat) [16].

FASTQ files with DNA sequencing data were aligned to the human reference genome (GRCh38) using Burrows-Wheeler Aligner [17], duplicate reads were marked by Picard MarkDuplicates. Using GATK BaseRecalibrator base quality scores were recalibrated and single nucleotide variants were called using GATK MuTect2 [18].

To evaluate correct normal-tumor pairing and any underlying contamination in the tumor samples, GATK calculate contamination and BAMix were used. The tumor mutational burden was calculated by summarizing the total number of non-synonymous, somatic mutations per sample with minimal variant allele frequency of 0.05 (5%). FATHMM prediction was used to predict functional consequences of non-coding and coding sequence variation [19].

RNA sequencing data were mapped with STAR (v2.7.3a) [20] to human reference genome using default settings. The read counts were computed with HTseq-count (v0.12.4) [21] and were analyzed with DESeq2 (v1.38.2) [22]. For the downstream analyses, data were analyzed using R (v4.2.2). Centering of normalized gene expression was performed by subtracting the row means and scaling by dividing the columns by the standard deviation. The Danaher immune cell [23], interferon-gamma (IFNγ) [24], micro-environment cell population (MCP counter) [25] gene expression signatures were analyzed and expressed in normalized z-scores.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were performed on patient and tumor characteristics using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 27. Overviews of RNA gene expressions levels were visualized with the tidyverse and reshape2 library in R.

Results

Patient characteristics

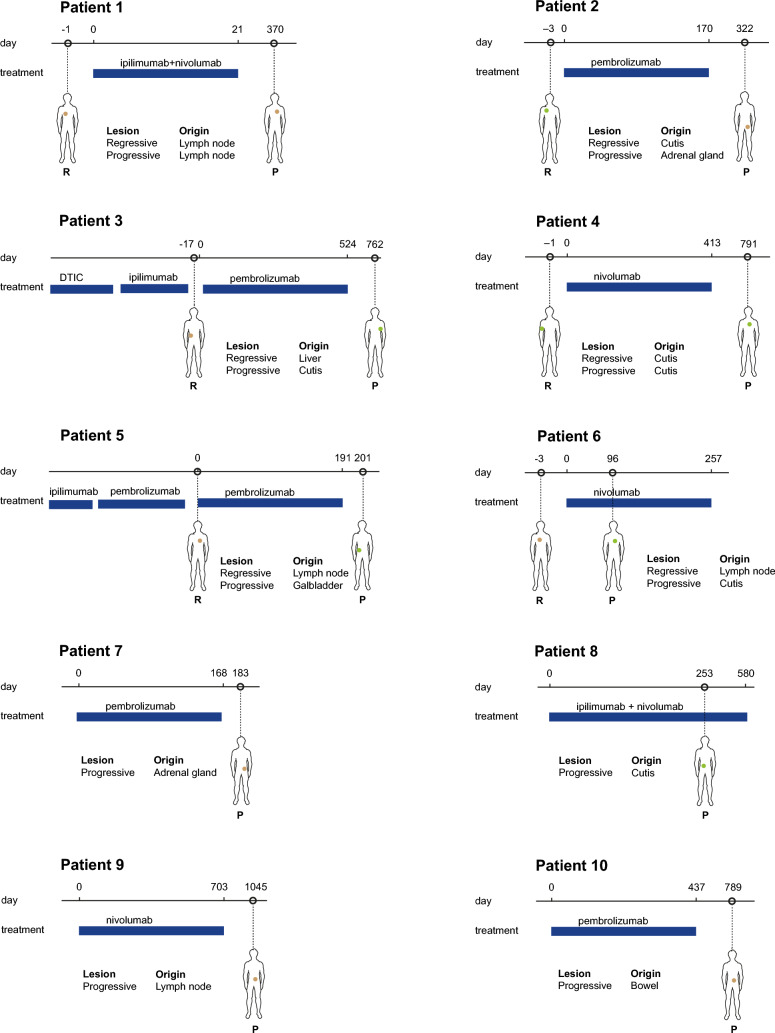

Ten patients were identified with available tumor samples at at least two time-points, with sufficient tumor material to send for sequencing. Of these patients, one patient had metachronous regressive and progressive tumor lesions of the same site (patient 1), two patients had metachronous regressive and novel tumor lesions at another site (patients 2 and 3), and three patients had metachronous regressive and progressive tumor lesions at different sites (patients 4–6) (Fig. 1). In addition, four patients had acquired resistant lesions without a comparative tumor lesion, as due to removal of the other tumor lesion for diagnostic purposes there was no known response of that specific lesion (patients 7–10).

Fig. 1.

Overview of patients and tumor lesions. Layout inspired in Fig. 1 of Liu et al. [26]

These ten patients were in majority male (80%), had cutaneous melanoma (90%) and were treatment-naïve (80%) (Table 1). Most patients had either BRAFV600E/K (40%) or NRAS (30%) mutation-positive melanoma, and half of the patients received pembrolizumab. All seven patients of whom performance status was recorded at baseline, had a WHO performance status of 0. Details of treatment per patient are depicted in Suppl. Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of patients included

| Patients (n = 10) | |

|---|---|

| Sex, male (n, %) | 8 (80%) |

| Age at start ICI (median, range) | 68 (35–78) |

| Primary melanoma | |

| Cutaneous | 9 (90%) |

| Unknown primary | 1 (10%) |

| Mutational status | |

| BRAF V600E/K | 4 (40%) |

| NRAS | 3 (30%) |

| BRAF V600E/K, NRAS + KIT wildtype | 3 (30%) |

| Prior systemic treatment* | 2 (20%) |

| Prior DTIC | 1 (10%) |

| Prior ICI | 2 (20%) |

| AJCC 8th edition at start ICI | |

| M1b | 4 (40%) |

| M1c | 4 (40%) |

| M1d | 2 (20%) |

| LDH < ULN at start ICI | 10 (100%) |

| ICI regimen | |

| Pembrolizumab | 5 (50%) |

| Nivolumab monotherapy | 3 (30%) |

| Ipilimumab + nivolumab | 2 (20) |

| Number of cycles ICI (median, range) | 21 (1–53) |

| Best overall response to ICI | |

| Complete response | 1 (10%) |

| Partial response | 6 (60%) |

| Progressive disease | 2 (20%) |

| Mixed response | 1 (10%) |

ICI immune checkpoint inhibitor, in table this refers to the ICI line on which dissociated response occurred, IQR interquartile range, ULN upper limit of normal

*One patient had two prior lines of treatment: DTIC and ipilimumab monotherapy

Characteristics of paired tumor lesions

In five out of six patients with paired tumor lesions, RNA sequencing data were available, while DNA sequencing data were available only in three patients, both due to insufficient material.

In patient 1 (metachronous progressive and regressive lesion), a higher number of CD8+ T cells was counted in the progressive lesion (+528 CD8+ cells/mm2). This was in contrast to both the Danaher and MCP counter immune cell subsets, which demonstrated lower T cell gene expression in the progressive lesion, ranging from −2.83 to −0.97 (Suppl. Fig. 1). In line with the progression, a lower IFNγ score (the average of the genes of the IFNγ signature, −1.937) was detected in the progressive lesion, while the PD-L1 expression on tumor cells was higher in the progressive lesion (10–50% vs. 1–10%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Overview of CD8, PD-L1, IFNγ and TMB levels of samples

| Patient | Regressive lesion | CD8+ cells/mm2 | PD-L1 tumor cells | IFNγ score | TMB level | Progressive lesion | CD8+ cells/mm2 | PD-L1 tumor cells | IFNγ score | TMB level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lymph node | 314 | 1–10% | 0.641 | – | Lymph node | 842 | 10–50% | −1.296 | − |

| 2 | Cutis | 1742 | 10–50% | 0.046 | 742 | Adrenal gland | 1629 | 10–50% | 0.534 | 482 |

| 3 | Liver | 225 | < 1% | −2.164 | − | Cutis | 521 | < 1% | −0.231 | − |

| 4 | Cutis | – | – | 0.148 | 717 | Cutis | 1094 | 10–50% | 0.877 | 4588 |

| 5 | Lymph node | 172 | 1–10% | −1.155 | – | Gall bladder | 250 | < 1% | 1.219 | − |

| 6 | Lymph node | – | – | – | 169 | Cutis | – | – | −0.388 | 894 |

| 7 | – | – | – | – | – | Adrenal gland | 762 | 1–10% | −0.015 | 741 |

| 8 | – | – | – | – | – | Cutis | 880 | 10–50% | 1.108 | 553 |

| 9 | – | – | – | – | – | Lymph node | 1161 | 1–10% | −0.177 | 327 |

| 10 | – | – | – | – | – | Bowel | 1042 | 1–10% | 0.030 | 1221 |

IFNγ interferon-gamma, TMB tumor mutational burden

Unlike for patient 1, both patients 2 and 3 had higher IFNγ scores (+ 0.488 and + 1.933) in their novel progressive versus the regressive lesion. Again, the CD8 T cell infiltration was similar or higher in the progressive lesion (1742 and 1629/mm2, and 225 and 521/mm2 in the regressive and progressive lesion, respectively), and this time in line with the Danaher and MCP counter immune cell subsets count (Suppl. Figs. 2 and 3). PD-L1 expression was similar between the regressive versus progressive lesion in both patients, but was high in one while low in the other patient (Table 2).

For the latter group of patients with progressive lesions at a different site (patients 4–6), data are incomplete. In general, again a higher CD8 infiltration and higher IFNγ signature levels in the progressive lesion was observed (Table 2), while the Danaher and MCP counter immune cell subsets were inconclusive (Suppl. Figures 4 and 5).

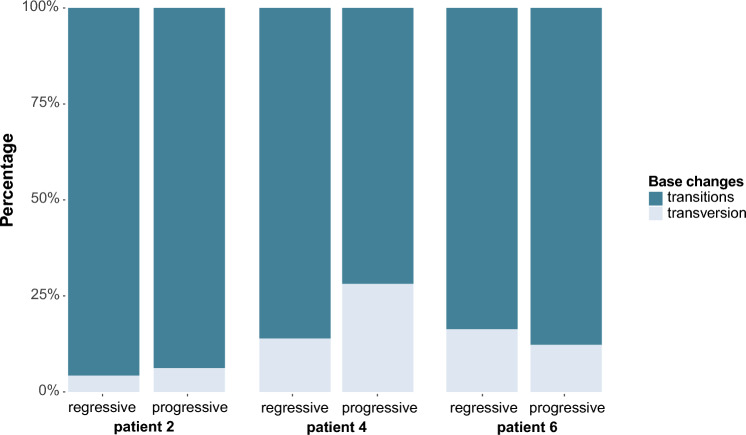

Due to lack of sufficient material, DNA sequencing analyses were only available for patient 2, 4 and 6. Patient 2 with a novel tumor lesion had only 2% difference in composition of mutational profile between lesions (Fig. 2), while TMB level (the total number of non-synonymous somatic mutations) was lower (-35%) in the novel lesion (Table 2). Patients 4 and 6, both with progressive lesions at a different site, had slight differences (14 and 4%, respectively) (Fig. 1), while TMB levels were evidently higher in the novel lesions (+ 540% and + 419%, respectively) (Table 2).

Fig. 2.

Overview of mutational profiles. Overview of transitions versus transversions of patients 2, 4 and 6

In addition, focused DNA mutation analyses were performed in both lesions (Suppl. Table 1). Only in patient 2 a pathogenic mutation (according to FATHMM prediction) was found in the regressive tumor lesion in the ATM gene (c.8494C > T) (Table 3). Although the progressive lesion of patient 4 had many mutations in the genes used for the focused DNA analyses, including different mutations in the HLA-A and HLA-C genes, the majority of these mutations was considered neutral according to FATHMM prediction (Table 3). No mutations were found in both lesions of patient 6 through focused DNA mutation analyses.

Table 3.

Overview of focused DNA mutation analyses of samples

| Patient | Lesion | Gene | Mutation | Mutation type | Variant | FATHMM prediction | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Regressive | ATM | c.8494C > T | p.Arg2832Cys | Missense mutation | SNP | Pathogenic (0.96) |

| 4 | Regressive | APC2 | c.3412G > A | p.Gly1138Arg | Missense mutation | SNP | – |

| 4 | Regressive | HLA-B | c.410A > C | p.His137Pro | Missense mutation | SNP | – |

| 4 | Regressive | APC2 | c.3412G > A | p.Gly1138Arg | Missense mutation | SNP | – |

| 4 | Progressive | EARP1 | c.35C > T | p.Thr12Ile | Missense mutation | SNP | Neutral (0.07) |

| 4 | Progressive | EGFR | c.1562G > A | p.Arg521Lys | Missense mutation | SNP | Neutral (0.05) |

| 4 | Progressive | FANCA | c.2426G > A | p.Gly809Asp | Missense mutation | SNP | Neutral (0.02) |

| 4 | Progressive | FANCA | c.796A > G | p.Thr266Ala | Missense mutation | SNP | – |

| 4 | Progressive | HLA-A | c.899_900inv | p.Leu300Pro | Missense mutation | DNP | – |

| 4 | Progressive | HLA-A | c.916A > G | p.Ile306Val | Missense mutation | SNP | Neutral (0.03) |

| 4 | Progressive | HLA-A | c.1005G > C | p.Lys335Asn | Missense mutation | SNP | Neutral (0.08) |

| 4 | Progressive | HLA-C | c.312C > A | p.Asn104Lys | Missense mutation | SNP | Neutral (0.01) |

| 4 | Progressive | HLA-C | c.302G > A | p.Ser101Asn | Missense mutation | SNP | Neutral (0.00) |

| 4 | Progressive | HLA-C | c.218C > A | p.Ala73Glu | Missense mutation | SNP | Neutral (0.04) |

| 4 | Progressive | NLRC5 | c.1358C > T | p.Pro453Leu | Missense mutation | SNP | Neutral (0.03) |

| 4 | Progressive | NLRC5 | c.1498 T > C | p.Cys500Arg | Missense mutation | SNP | Neutral (0.09) |

| 4 | Progressive | RFX5 | c.1226C > G | p.Pro409Arg | Missense mutation | SNP | – |

| 4 | Progressive | TAPBP | c.779C > G | p.Thr260Arg | Missense mutation | SNP | Neutral (0.12) |

| 4 | Progressive | TNFRSF1A | c.362G > A | p.Arg121Gln | Missense mutation | SNP | – |

| 7 | Progressive | ERAP2 | c.22G > A | p.Val8Ile | Missense mutation | SNP | – |

| 7 | Progressive | NLRC5 | c.1934C > T | p.Pro645Leu | Missense mutation | SNP | – |

| 7 | Progressive | POLE | c.4514C > T | p.Pro1505Le | Missense mutation | SNP | Pathogenic (1.00) |

| 8 | Progressive | B2M | c.240G > A | p.Trp80Ter | Non-sense mutation | SNP | – |

| 8 | Progressive | PTEN | c.821G > A | p.Trp274Ter | Non-sense mutation | SNP | Pathogenic (1.00) |

| 10 | Progressive | ATM | c.8801C > T | p.Thr2934Ile | Missense mutation | SNP | – |

| 10 | Progressive | BTLA | c.157C > T | p.Pro53Ser | Missense mutation | SNP | – |

| 10 | Progressive | LAG3 | c.484C > T | p.Leu162Phe | Missense mutation | SNP | – |

| 10 | Progressive | PD-1 | c.782C > T | p.Ser261Phe | Missense mutation | SNP | – |

SNP single nucleotide polymorphism, DNP double nucleotide polymorphisms

Characteristics of acquired resistant lesions

Additional analyses were available for four patients with progressive tumor lesions after initial response (the responding tumor lesions of these patients were not available for analysis). High CD8 infiltration (range 762–1161 CD8+ cells/mm2) and relatively high IFNγ signature levels (range −0.177 to 1.108) were observed compared to both the regressive and progressive lesions of the previously described patients (Table 2).

DNA sequencing analyses were available of three patients. TMB levels were variable between these patients (range 327–1221) (Table 2). Two non-sense (stop gained) mutations in the B2M (c.240G > A) and PTEN (c.821G > A, pathogenic according to FATHMM prediction) genes of patients 8 were observed (Table 3). Patient 7 had one pathologic missense mutations in POLE (c.4514C > T), while patient 10 had only missense mutations. In the lesions of patient 9, no mutations were found through the focused analyses.

Discussion

As the biological mechanisms underlying dissociated response to ICI are still largely unknown, we have investigated paired tumor lesions of patients with such a response. Tumor immune exclusion [27–29] was in general not observed, as in all progressive lesions immune cell infiltrates were found and in the majority even at higher levels than in the regressive tumor lesion. Due to the unavailability of viable tumor material, unfortunately no co-culture experiments dissecting tumor-specific T cell infiltrates from bystander T cell tumor infiltration could be performed. Thus, we could not confirm the notion that an immune exclusive phenotype [27–29] is responsible for the lack of response to ICI.

In addition, the genetic make-up of progressive tumor lesions did not deliver conclusive explanations for ICI resistance. In the three different groups of patients with paired tumor lesions, mutational profiles showed only 2–14% difference between regressive and progressive lesions. Progressive lesions at a different site, however, had a 429–540% increase in TMB levels, while only the newly emerged tumor lesion had a lower TMB level compared to their regressive lesions (−35%). A high TMB level has been associated with response to ICI in melanoma [30, 31], but no data are available on TMB levels within one patient in both regressive and progressive tumor lesions.

Furthermore, when analyzing for potential mutations responsible for tumor immune escape, only in one of the patients with a non-paired acquired resistant tumor lesion, stop-gaining mutations were found in the B2M and PTEN genes. B2M plays a role in stabilization of the MHC class I molecules at the cell surface, which on their turn are of importance in antigen presentation and the subsequent recognition of the immune system [32]. Alterations in this gene are previously described in melanoma patients with acquired resistance to ICI [28, 33] and also in patients with lung cancer [34] and mismatch repair-deficient cancers [35]. In our patient, we have not confirmed the loss of expression of B2M or MHC-I expression in the tumor by immunohistochemistry due to lack of sufficient tumor material. Data in pathways related to MHC expression (data not shown) were not easily to interpret as these levels are relative compared to the total patient set and no paired sample with known response at lesion-level was available for this patient.

PTEN loss has been previously described in one patient with melanoma who developed acquired resistance to ICI [36]. Loss of function of PTEN diminishes T cell priming; by loss of activation of phosphoinositide-3 kinase lipidation of autophagosome protein LC3 is inhibited and subsequently autophagy of tumor cells is inhibited [37]. PTEN negative melanoma tumors, defined by immunohistochemistry staining, are related to poor patient outcome and absence of T cell infiltration [38].

The other pathogenic mutation found in our analysis was in the POLE gene of another patient with a non-paired acquired resistant tumor lesion. DNA polymerase epsilon (POLE) plays, together with polymerase delta 1 (POLD1), an important role in DNA damage response and both have an important role in DNA replication by proofreading [39]. In a retrospective analysis of patients with various cancer types, pathogenic mutations in POLE were associated with clinical benefit to ICI [40]. Another study demonstrated that both POLE and POLD1 mutations could be a promising predictive biomarker of ICI response [41].

Other mechanisms of immune escape previously described in melanoma patients, such as mutations in the JAK1 and JAK2 gene [33, 42, 43], were not observed in our cohort.

All patients included in this work had favorable patient characteristics, with low lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels and a good performance status. These are the patients who often have durable benefit of ICI treatment [44, 45]. Our idea was that inclusion of patients with proved anti-tumor immune response and performing an intrapatient comparison with a progressive tumor lesion might be the cleanest approach to identify mechanism of ICI resistance, but this unfortunately failed in our hands.

Previous studies have shown low TMB levels, HLA loss, low CD8 infiltration, low LAG-3 or low TIM-3 expression to be associated with lower chance of response [12, 40, 43, 46], but when addressing our intrapatient analyses of regressive versus progressive tumor lesions, these parameters did not validate. Of interest, the majority of patients with higher levels of CD8 T cell infiltration and IFNγ expression in the progressive tumor lesions, did have response to the ICI line given after the biopsy was taken. Albeit our translational data of one metastatic lesion will not necessarily be a correct representation of response on patient-level, this is an interesting observation.

Although this descriptive study consists of a small number of patients, it provides nonetheless an overview of (largely) paired tumor lesion analyses in this field in which a lot is still to be discovered and understood. Of note, due to the normalization methods applied to RNA sequencing data, levels described are relatively high or low within this specific subset of patients, which could make comparison to data in other studies difficult. A challenge arising with our DNA sequencing data is that one comes across different mutations of which the consequences are not known. The FATHMM prediction tool [19] helps herein by providing a predictive neutral or pathogenic score based on prior literature, but nonetheless the largest part of mutations found in our patients could not be traced back to previous studies.

As in the majority of patients the paired tumor lesions did not origin from the same organ, organ-specific effects could affect our results [47]. A study that looked into site-specific patterns of response to ipilimumab and nivolumab demonstrated a significant inter- and intrapatient heterogeneity in response and progression [48]. This presumably reflects differences in underlying molecular heterogeneity, as, for example, the liver has an immune suppressive microenvironment and is associated with worse outcome than metastases in the lung [48, 49]. In the liver sample of patient 3, a low IFNγ score was seen, which can probably not fully be contributed to the tumor itself but can partly be explained by the liver microenvironment. The different sites of the tumor lesions and the difference in immunogenicity depending on the organ in which the metastasis developed [47, 50] complicate the comparison of our data between regressive and progressive tumor lesions.

Our study confirms the challenges in identifying mechanisms of immune escape, which seem to be very individual per patient, and even per metastasis, while parameters associated with response (such as high neoantigen load, CD8 infiltration and high IFNγ signature) are easier to identify. Hence, we still have a long way to go until we understand resistance mechanisms to ICI.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank all patients for participating in the biobank study. We would like to acknowledge the NKI- AVL Core Facility Molecular Pathology & Biobanking (CFMPB) for supplying NKI-AVL Biobank material and lab support.

Author’s contribution

JMV and CUB designed the study. JMV collected patient data, selected tumor samples and analyzed and interpreted clinical and translational data and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. EPH provided valuable input on the project. HS and PD performed bioinformatics analyses. JS scored the immunohistochemistry stainings. AB was responsible for the RNA isolations and performance of the staining of the biopsies. All authors interpreted the data, reviewed the manuscript, and approved the final version.

Funding

None declared.

Data availability

Data are available upon reasonable request for academic use and within the limitations of the provided informed consent. Every request will be reviewed by the institutional review board of the NKI; the researcher will need to sign a data access agreement with the NKI after approval.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

PD reported financial interest in Signature Oncology and will receive some possible revenues if the IFNγ signature is being developed as a clinical companion diagnostic. CUB received compensation (all paid to the institute except TRV) for advisory roles for Bristol-Myers Squibb, MSD, Roche, Novartis, GSK, AZ, Pfizer, Lilly, GenMab, Pierre Fabre, Third Rock Ventures; received research funding (all paid to the institute) from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, NanoString, and declares stockownership in Immagene BV, where he is co-founder. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Patients who did not opt out for use of remaining tumor material for research purpose or had giving informed consent for performing additional biopsies for research purposes, were screened for availability of tumor samples after local institutional review board approval (IRBd19-095 and IRBm19-130), in accordance with national privacy and ethics guidelines.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Robert C, Long GV, Brady B, et al. Nivolumab in previously untreated melanoma without BRAF mutation. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(4):320–330. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1412082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Larkin J, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, et al. Five-year survival with combined nivolumab and ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(16):1535–1546. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1910836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schachter J, Ribas A, Long GV, et al. Pembrolizumab versus ipilimumab for advanced melanoma: final overall survival results of a multicentre, randomised, open-label phase 3 study (KEYNOTE-006) Lancet. 2017;390(10105):1853–1862. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31601-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bellmunt J, de Wit R, Vaughn DJ, et al. Pembrolizumab as second-line therapy for advanced urothelial carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(11):1015–1026. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1613683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Motzer RJ, Escudier B, McDermott DF, et al. Nivolumab versus everolimus in advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(19):1803–1813. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1510665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferris RL, Blumenschein G, Jr, Fayette J, et al. Nivolumab for recurrent squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(19):1856–1867. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1602252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Borghaei H, Paz-Ares L, Horn L, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(17):1627–1639. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1507643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pons-Tostivint E, Latouche A, Vaflard P, et al. Comparative analysis of durable responses on immune checkpoint inhibitors versus other systemic therapies: a pooled analysis of phase III trials. JCO Precis Oncol. 2019;3:1–10. doi: 10.1200/PO.18.00114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jansen YJL, Rozeman EA, Mason R, et al. Discontinuation of anti-PD-1 antibody therapy in the absence of disease progression or treatment limiting toxicity: clinical outcomes in advanced melanoma. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(7):1154–1161. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Borcoman E, Kanjanapan Y, Champiat S, et al. Novel patterns of response under immunotherapy. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(3):385–396. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jenkins RW, Barbie DA, Flaherty KT. Mechanisms of resistance to immune checkpoint inhibitors. Br J Cancer. 2018;118(1):9–16. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2017.434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharma P, Hu-Lieskovan S, Wargo JA, et al. Primary, adaptive, and acquired resistance to cancer immunotherapy. Cell. 2017;168(4):707–723. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anagnostou V, Smith KN, Forde PM, et al. Evolution of neoantigen landscape during immune checkpoint blockade in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Discov. 2017;7(3):264–276. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-16-0828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morad G, Helmink BA, Sharma P, et al. Hallmarks of response, resistance, and toxicity to immune checkpoint blockade. Cell. 2021;184(21):5309–5337. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jiang H, Lei R, Ding SW, et al. Skewer: a fast and accurate adapter trimmer for next-generation sequencing paired-end reads. BMC Bioinformatics. 2014;15:182. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-15-182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Andrew S (2010) FastQC: a qualit control tool for high throughput sequence data 2010 [Available from: https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/]

- 17.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(14):1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van der Auwera GA, Carneiro MO, Hartl C, et al. From FastQ data to high-confidence variant calls: the genome analysis toolkit best practices pipeline. Curr Protoc Bioinform. 2013;43(1):11.10.11–11.10.33. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi1110s43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.http://fathmm.biocompute.org.uk/

- 20.Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F, et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 2013;29(1):15–21. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Putri GH, Anders S, Pyl PT, et al. Analysing high-throughput sequencing data in Python with HTSeq 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2022;38(10):2943–2945. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btac166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15(12):550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Danaher P, Warren S, Dennis L, et al. Gene expression markers of Tumor Infiltrating Leukocytes. J Immunother Cancer. 2017;5:18. doi: 10.1186/s40425-017-0215-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ayers M, Lunceford J, Nebozhyn M, et al. IFN-γ-related mRNA profile predicts clinical response to PD-1 blockade. J Clin Invest. 2017;127(8):2930–2940. doi: 10.1172/JCI91190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Becht E, Giraldo NA, Lacroix L, et al. Estimating the population abundance of tissue-infiltrating immune and stromal cell populations using gene expression. Genome Biol. 2016;17(1):218. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-1070-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu D, Lin JR, Robitschek EJ, et al. Evolution of delayed resistance to immunotherapy in a melanoma responder. Nat Med. 2021;27(6):985–992. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01331-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang MM, Coupland SE, Aittokallio T, et al. Resistance to immune checkpoint therapies by tumour-induced T-cell desertification and exclusion: key mechanisms, prognostication and new therapeutic opportunities. Br J Cancer. 2023;129(8):1212–1224. doi: 10.1038/s41416-023-02361-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sade-Feldman M, Jiao YJ, Chen JH, et al. Resistance to checkpoint blockade therapy through inactivation of antigen presentation. Nat Commun. 2017;8(1):1136. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01062-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spranger S, Bao R, Gajewski TF. Melanoma-intrinsic beta-catenin signalling prevents anti-tumour immunity. Nature. 2015;523(7559):231–235. doi: 10.1038/nature14404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Snyder A, Makarov V, Merghoub T, et al. Genetic basis for clinical response to CTLA-4 blockade in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(23):2189–2199. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1406498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van Allen EM, Miao D, Schilling B, et al. Genomic correlates of response to CTLA4 blockade in metastatic melanoma. Science. 2015;350(6257):207–211. doi: 10.1126/science.aad0095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hulpke S, Tampé R. The MHC I loading complex: a multitasking machinery in adaptive immunity. Trends Biochem Sci. 2013;38(8):412–420. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2013.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zaretsky JM, Garcia-Diaz A, Shin DS, et al. Mutations associated with acquired resistance to PD-1 blockade in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(9):819–829. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1604958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gettinger SN, Wurtz A, Goldberg SB, et al. Clinical features and management of acquired resistance to PD-1 axis inhibitors in 26 patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2018;13(6):831–839. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2018.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Le DT, Durham JN, Smith KN, et al. Mismatch repair deficiency predicts response of solid tumors to PD-1 blockade. Science. 2017;357(6349):409–413. doi: 10.1126/science.aan6733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Trujillo JA, Luke JJ, Zha Y, et al. Secondary resistance to immunotherapy associated with β-catenin pathway activation or PTEN loss in metastatic melanoma. J Immunother Cancer. 2019;7(1):295. doi: 10.1186/s40425-019-0780-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spranger S, Gajewski TF. Impact of oncogenic pathways on evasion of antitumour immune responses. Nat Rev Cancer. 2018;18(3):139–147. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2017.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cabrita R, Mitra S, Sanna A, et al. The role of PTEN loss in immune escape, melanoma prognosis and therapy response. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12(3):742. doi: 10.3390/cancers12030742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang J, Shih DJH, Lin SY. Role of DNA repair defects in predicting immunotherapy response. Biomark Res. 2020;8:23. doi: 10.1186/s40364-020-00202-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vukadin S, Khaznadar F, Kizivat T, et al. Molecular mechanisms of resistance to immune checkpoint inhibitors in melanoma treatment: an update. Biomedicines. 2021;9(7):835. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines9070835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang F, Zhao Q, Wang YN, et al. Evaluation of POLE and POLD1 mutations as biomarkers for immunotherapy outcomes across multiple cancer Types. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(10):1504–1506. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.2963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sucker A, Zhao F, Pieper N, et al. Acquired IFNgamma resistance impairs anti-tumor immunity and gives rise to T-cell-resistant melanoma lesions. Nat Commun. 2017;8:15440. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gide TN, Wilmott JS, Scolyer RA, et al. Primary and acquired resistance to immune checkpoint inhibitors in metastatic melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24(6):1260–1270. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-2267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ribas A, Hamid O, Daud A, et al. Association of pembrolizumab with tumor response and survival among patients with advanced melanoma. JAMA. 2016;315(15):1600–1609. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.4059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schadendorf D, Long GV, Stroiakovski D, et al. Three-year pooled analysis of factors associated with clinical outcomes across dabrafenib and trametinib combination therapy phase 3 randomised trials. Eur J Cancer. 2017;82:45–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2017.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ziogas DC, Theocharopoulos C, Koutouratsas T, et al. Mechanisms of resistance to immune checkpoint inhibitors in melanoma: What we have to overcome? Cancer Treat Rev. 2023;113:102499. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2022.102499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Salmon H, Remark R, Gnjatic S, et al. Host tissue determinants of tumour immunity. Nat Rev Cancer. 2019;19(4):215–227. doi: 10.1038/s41568-019-0125-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pires da Silva I, Lo S, Quek C, et al. Site-specific response patterns, pseudoprogression, and acquired resistance in patients with melanoma treated with ipilimumab combined with anti-PD-1 therapy. Cancer. 2020;126(1):86–97. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tumeh PC, Hellmann MD, Hamid O, et al. Liver metastasis and treatment outcome with anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody in patients with melanoma and NSCLC. Cancer Immunol Res. 2017;5(5):417–424. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-16-0325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hegde PS, Chen DS. Top 10 challenges in cancer immunotherapy. Immunity. 2020;52(1):17–35. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request for academic use and within the limitations of the provided informed consent. Every request will be reviewed by the institutional review board of the NKI; the researcher will need to sign a data access agreement with the NKI after approval.