Abstract

Introduction

For signal detection studies investigating either drug safety or method evaluation, the choice of drug-outcome pairs needs to be tailored to the planned study design and vice versa. While this is well understood in hypothesis-testing epidemiology, it should be as important in signal detection, but this has not widely been considered. There is a need for a taxonomy framework to provide guidance and a systematic reproducible approach to the selection of appropriate drugs and outcomes for signal detection studies either investigating drug safety or assessing method performance using real-world data.

Objective

The aim was to design a general framework for the selection of appropriate drugs and outcomes for signal detection studies given a study design of interest. As a motivating example, we illustrate how the framework is applied to build a reference set for a study aiming to assess the performance of the self-controlled case series with active comparators.

Methods

We reviewed criteria presented in two published studies which aimed to provide practical advice for choosing the appropriate signal evaluation methodology, and assessed their relevance for signal detection. Further characteristics specific to signal detection were added. The final framework is based on: the application of study design requirements, the database(s) of interest, and the clinical importance of the drug(s) and outcome(s) under consideration. This structure was applied by selecting drug-outcome pairs as a reference set (i.e. list of drug-outcome pairs classified as positive or negative controls) for which the method is expected to work well for a signal detection study aiming to assess the performance of self-controlled case series. Eight criteria were used, related to the application of self-controlled case series assumptions, choice of active comparators, coverage in the database of interest and clinical importance of the outcomes.

Results

After application of the framework, two classes of antibiotics (seven drugs) were selected for the study, and 28 outcomes from all organ classes were chosen from the drug labels, out of the 273 investigated. In total, this corresponds to 104 positive controls (drug-outcome pairs) and 58 negative controls.

Conclusions

We proposed and applied a framework for the selection of drugs and outcomes for both drug safety signal detection and method assessment used in signal detection to optimise their performance given a study design. This framework will eliminate part of the bias relating to drugs and outcomes not being suited to the method or database. The main difficulty lies in the choice of the criteria and their application to ensure systematic selection, especially as some information remains unknown in signal detection, and clinical judgement was needed on occasions. The same framework could be adapted for other methods.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40264-023-01382-5.

Key Points

| We present a framework for the selection of drugs and outcomes based on the study design of interest; to optimise the performance of real-world data signal detection studies. |

| This framework aims to address bias relating to drugs and outcomes not being suited to the study design of choice. |

| We applied this framework to build a reference set for a study aiming to assess the performance of the self-controlled case series with active comparators. |

Introduction

Epidemiological methods are differentially valid depending on the nature of the drug and outcome [1]. Although this is well understood in traditional epidemiology, it has not fully been considered in real-world data signal detection studies, especially at the design stage. While it is clearly impractical to conduct bespoke analyses for every individual drug-outcome pair in a transparent auditable manner [2], many signal detection studies have been conducted with minimal consideration of the drug-event pairs to be analysed. Authors implemented a generic approach in the same way for all the drug-event or vaccine-event pairs, leading to suboptimal performances of signal detection methods, with high numbers of false-positive and false-negative findings [3]. In recent years there have been multiple efforts to standardise and harmonise elements of study design and reporting through the introduction of frameworks and other guidance.

The US Food and Drug Administration’s Mini-Sentinel Taxonomy Work Group initiated the approach of considering a systematic framework for tailoring the study design choice to the specific characteristics of drug-outcome pairs in hypothesis-testing studies using real-world data (RWD). Their work holds relevance for signal detection, although adaptations would be needed to include specificities of signal detection. The aim of the Mini-Sentinel Taxonomy Work Group was “To characterize analytic methods suitable for signal refinement and to provide clarity and practical advice for choosing the appropriate signal refinement methodology for the Mini-Sentinel System” [4]. They proposed a framework for how, based on attributes of the drug of interest (DOI) and health outcomes of interest (HOI), one could and should decide between a between- and a within-person comparison method. Another independent sentinel component developed a structured decision table for method selection in vaccine signal detection [5]. Similar criteria to the Mini-Sentinel study were used, but some were removed because only vaccines were considered, and they provided more granularity on methods with specific choices. Although this was developed for vaccine signal detection, this is also relevant to drug safety signal detection with some adjustments, to account for, for example, the common difference between healthy and diseased indicated populations and duration of use.

The Mini-Sentinel study findings translate to the impact of the choice of epidemiological methods on signal detection performance, and specifically the ability to anticipate where there will be suboptimal signal detection performance for a specific method given the nature of the exposure and outcome. This could be considered in two ways, either (1) picking the DOIs and HOIs first (drug/outcome-based approach), similarly to the Mini-Sentinel work, or (2) choosing a method and selecting the DOIs and HOIs based on the characteristics of that method (method-based approach).

Unless a prospective open-ended evaluation approach is taken and signals are reviewed as they are identified [6], the most common approach to the evaluation of signal detection is retrospectively examining method performance to some external benchmark reference set [7, 8]. One of the problems with assessing signal detection methods in RWD-based analyses is that most studies to date have used broad reference sets containing a wide range of exposures and outcomes for evaluation; irrespective of the characteristics of the method they were trying to evaluate. Ensuring a priori-defined appropriate references sets (i.e. a list of drug-outcome pairs classified as positive or negative controls) of DOIs and HOIs will enable more effective and accurate method assessments. This should therefore account for the nature of the DOIs and HOIs and other aspects that affect the performance of the method. More broadly, ensuring the choice of DOIs and HOIs is suitable for the chosen study design can increase performances of signal detection methods in large datasets.

There is therefore a clear need to develop a framework to enable consistent and transparent approaches in the choice of DOIs and HOIs for signal detection studies, which is not only for signal detection studies to investigate drug safety but can also be applied to the development of reference sets for signal detection method evaluation. The framework presented here will be applicable to signal detection studies where a list of predefined outcomes of potential interest has been decided. This could be done for example, by combining lists of general important adverse reactions in pharmacovigilance [9], known adverse reactions for other drugs within the same class and pharmacologically plausible adverse reactions. For more open-ended signal detection without a priori events of interest, other solutions would be needed to obtain a list of outcomes, but that is not the focus of this paper.

Purpose

In this study, we aim to build a systematic framework for the selection of appropriate DOIs and HOIs for signal detection studies based on a study design of interest. As a motivating example, we illustrate how the framework is applied to build a reference set for a study aiming to assess the performance of self-controlled designs with active comparators.

Methods

Presentation of the General Framework

Our framework is based on the characteristics presented in the published studies presented above [5, 10]. Key characteristics for design choice were: (1) the strength of confounding (both between person and within person); (2) the circumstances that could lead to misclassification of: the exposure or the timing of the HOI; and (3) the sustained or acute nature of the exposure. The final report presented a scoring system to evaluate whether a within-person comparison or a between-person comparison would be more appropriate, depending on the DOI, the HOI and other characteristics of the study [10]. The full list is presented in the Electronic Supplementary Material (ESM). We reviewed all the criteria and assessed their relevance for signal detection. For example, in a signal detection study, the number of comparator groups or the relationship between frequency of DOI use and incidence of the HOI are unknown. Building on their list of criteria, we added other characteristics, such as the public health importance, that were specific to signal detection but were not considered in existing studies.

We propose a method-based approach to choose suitable exposures and outcomes for a specific method of interest, recognising that a single method is not optimal for all exposures and outcomes. This approach enables a single study design to be applied for several types of drugs and outcomes if they share similar characteristics, as well as allows an assessment of performance of the chosen design. It also explicitly involves stating which exposures and outcomes are not suitable for the chosen design.

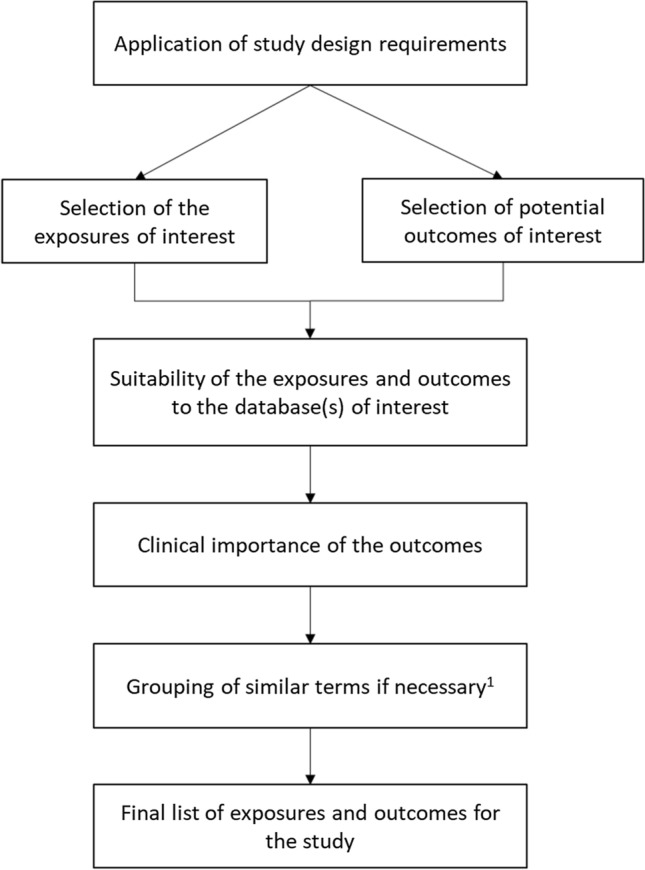

Our general framework proposition is presented in Fig. 1. Starting from a method of interest, it enables the choice of appropriate drugs and outcomes to conduct a signal detection study with this method. It is based on:

- The application of study design requirements, which includes:

-

otransient or sustained nature of the exposure;

-

olong- or short-term nature of the outcome: length of the risk window;

-

oimmediate- or delayed-risk window;

-

osusceptibility to within- and between-person confounding.

-

o

The database(s) of interest.

The clinical importance of the outcome(s).

Fig. 1.

Summary of the general framework. 1Depending on the coding system (ICD-10, Read Codes), similar clinical terms for outcomes could be grouped

Application of the Framework: A Self-Controlled Study with Active Comparators

We anticipate that the framework should be both method and applied example agnostic. We set out to examine the application of the framework for an exemplar, to develop a reference set for a study aiming to assess the performance of the self-controlled case series (SCCS) for signal detection. However, the general principles we propose are equally applicable to both fully exploratory signal detection and method performance assessment.

We chose for this initial assessment self-controlled designs, as they were found to be the highest-performing methods for signal detection among other designs (e.g. cohort studies, disproportionality analyses) in a recent literature review [3]. Specifically, we selected for testing the SCCS, which is a case-only design comparing the event rate during exposed and unexposed time within the same individual [11]. One previous limitation with this method was the lack of tools to deal with time-varying confounding, such as the use of active comparators, but this has been recently implemented [12] for epidemiological studies and this could potentially improve their signal detection performance further. We therefore decided to use SCCS with active comparators in this example.

The main database of interest is the Clinical Research Practice Datalink (CPRD) Aurum, which contains records from general practitioners in the UK. The study will be replicated in the Systeme National des Donnees de Sante, a nationwide public claims database from France, and in IBM Marketscan, a private claims database from the USA.

Using the framework, we aimed to select drugs and outcomes for which the SCCS is expected to work well. This is to be able to assess the performance of this method using the reference set developed here.

Selection Process for the Case Study

We adapted our proposed general framework presented above as follows for the case study, taking into account the assumptions of the SCCS and the presence of active comparators (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Overview of the selection process

Box 1. Detailed selection process of the drugs of interest (DOIs) and health outcomes of interest (HOIs).

Positive controls

Selection of the DOIs

Requirement for application of self-controlled case series (SCCS): works best with short-term exposure.

Choice: antibiotics, specifically macrolides (erythromycin, azithromycin, clarithromycin) and fluoroquinolones (ciprofloxacin, ofloxacin, levofloxacin, moxifloxacin).

Rationale: for most indications, the recommended lengths of prescriptions vary between 3 and 7 days, with the longest treatment duration of at 14 days in an adult population [13]: meets the short-term exposure criteria.

-

(2)

Selection of the active comparators

Constraints: similar indications as macrolides and fluoroquinolones respectively, but with a different safety profile.

Choice: amoxicillin and cefalexin.

Rationale: share common indications with the DOIs and have been used in previous studies [14–16].

Drawbacks: although the indications are similar, there are potential differences in the severity of the infections for which these drugs are prescribed [17].

-

(3)

Selection of potential HOIs

Looked at product characteristics (Summary of Product Characteristics) from https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc in February 2021.

Listed all adverse events from the Summary of Product Characteristics for all the DOIs in tablet form for potential inclusion in the reference set.

-

(4)

Elimination of potential HOIs

Broad generic terms that do not refer to a specific diagnosis. The need for specific definitions has been demonstrated in previous studies [18]. Example: taste disorders, respiratory disorders.

Terms referring to patients with a specific underlying treatment/diagnosis because our study focusses on adverse drug reactions (ADRs) in the general population. Example: hypoglycaemia in diabetic patients treated with hypoglycaemic agents.

Terms referring to an increase/decrease in a biological value, not a diagnosis. These were eliminated mainly because such data are inconsistently reported in healthcare databases. Example: blood creatinine increased.

Terms referring to children only because our population is adults only. It would be possible to do a similar study using a paediatric population. Example: infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis.

Terms referring to intravenous form only because most of our data comes from primary care or pharmacy, no data on medication given in hospital are available. Example: injection-site inflammation.

-

(5)

Application of SCCS assumptions to the HOIs

We included all outcomes that meet all SCCS assumptions as follows:

- Acute and easily dated outcomes [19]

-

oDefinition: events likely to occur within 30 days of the first DOI prescription.

-

oSearched for studies looking at the association between the antibiotics and the HOI, or for clinical reports of the HOI after antibiotic use. If reported time to onset in these studies was frequently shorter than 30 days, the outcome was considered acute.

-

oIf no study was available, background experience was used by obtaining a consensus from pharmacoepidemiologists and clinicians.

-

o

- Rare or independently recurrent outcomes [19]

-

oIn the SPCs, apart from nausea and diarrhoea, all adverse reactions have observed frequencies below 3%, which were considered as rare. An independently recurrent outcome is not a concern because a simple workaround is to consider the first event only.

-

o

The HOI does not influence the probability of later exposure [19]: this may not be true when the outcome is on the label, but will often relate to the choice of observation period if there is a period of time before the causal nature of the ADR was known.

The HOI does not influence observation time [20]: the percentage of short-term mortality (within 30 days of the outcome) was checked for events with a potential significant increase in mortality using the literature. If survival is below 90%, the outcome was removed because the assumption was considered unmet.

-

(6)

Coverage in Clinical Research Practice Datalink (CPRD) Aurum

As CPRD Aurum is the main database for the analysis, only outcomes expected to be well captured in this database were included in the reference set. Events were classified as likely to be “well captured”, “under captured” or “not well captured” using expertise from clinicians and results cross-checked with pharmacoepidemiologists, as well as studies exploring the HOIs in CPRD Aurum when available. Examples of “well-captured” events included anaphylactic shock and transient vision loss because it is expected that most cases will result in a general practitioner (GP) or hospital visit and be therefore captured in CPRD Aurum. On the contrary, diarrhoea and dry skin were considered “not well captured” because a majority of cases could be self-limiting and would not result in interactions with healthcare, particularly in healthy adults. Gastroenteritis and hypoglycaemia were considered “under-captured” because only severe cases would result in a GP/hospital visit. “Not well-captured” events were ruled out regardless of the numbers of occurrence in the database. “Under-captured” events were ruled out if the total number of events reported in the whole database was under <20,000 in the CPRD Aurum Code browser (May 2022 build, most recently available).

Coverage was checked in the two other databases (Systeme National des Donnees de Sante and MarketScan) during the planning phase before conducting any analysis to make sure it was possible to investigate the chosen outcomes in these databases. This was more difficult as the numbers of events were not available without full access to the databases. These databases are much larger than the CPRD in total numbers of patients, thus power is likely to be less of an issue in Systeme National des Donnees de Sante and MarketScan.

-

(7)

Importance and Seriousness of ADRs

We furthermore classified the reference set as below.

Level 1: Symptom rather than specific disease

Level 2: Disease often self or pharmacy treated, only severe cases requiring a GP visit

Level 3: Disease requiring a GP visit and medication in most cases

Level 4: Disease requiring a specialist visit or short-term hospitalisation with a small increase in mortality

Level 5: Disease requiring long-term hospitalisation and likely high mortality

By definition, if a disease diagnosis requires a laboratory test, the event was classified as level 3 as the GP must have requested the test.

Outcomes classified as level 1 or 2 were ruled out for inclusion because they are less likely to be of a major public health impact. They also tend to be poorly captured in the CPRD or other healthcare databases, even if they had a large number in step (6) because they are common HOIs. Level 3 and 4 outcomes were kept, whilst level 5 outcomes were already removed in step 5 because of leading to a large increase in mortality.

This is an optional step: all the outcomes meeting the other criteria could have been included in our signal detection study. We decided to reduce the size of the reference set because of the limited time for implementation.

-

(8)

Outcome Does Not Present on Active Comparator’s Label

If an adverse event is shared between the DOI and the active comparator, it cannot be studied in the analysis with an active comparator. Therefore, we removed the outcomes that were present on one of the comparator’s UK label.

Negative Controls For the negative controls, we started from the same HOIs selected as positive controls to ensure homogeneity between positive and negative controls. Different drugs were used, for which the outcomes are not labelled as HOIs for any of the drugs in the same class. For example, no fluoroquinolones have pneumonia on their label, so that pneumonia can be considered a negative control outcome for all fluoroquinolones .

In addition, we considered two external outcomes that have been used in several performance assessment studies [21]: hip fracture and gastrointestinal bleeding. We chose these HOIs as they are not reported to be associated with any antibiotics, so can be considered as “gold standard”.

Results

Initially, 273 outcomes were found on the drugs’ labels and considered for inclusion. After applying our proposed framework to the case study, 28 outcomes were selected in the reference set. A flowchart of inclusion is presented in Fig. 3. The list of outcomes excluded at each step can be found in the Appendix in the ESM. In total, 104 positive controls (individual drug-outcome pairs) and 58 negative controls were included in the reference set.

Fig. 3.

Application of the framework for the selection of the reference set in the study. CPRD Clinical Research Practice Datalink, SCCS self-controlled case series

The positive control outcomes included in the reference set are listed below by organ class. The list of the negative control outcomes is the same with the addition of hip fracture and gastrointestinal bleeding, as explained in the methods section. Table 1 illustrates the full list of the positive and negative control outcomes for ciprofloxacin and clarithromycin as examples for fluoroquinolones and macrolides, respectively.

Infections and infestations: pneumonia and cellulitis

Blood and lymphatic system disorders: thrombocythemia and pancytopenia

Immune system disorder: anaphylactic shock

Psychiatric disorders: delirium

Nervous system disorders: intracranial hypertension, amnesia, vertigo, gait disturbance and peripheral neuropathy

Eye disorders: transient vision loss and uveitis

Ear and labyrinth disorders: tinnitus and hearing loss

Cardiac disorders: syncope, atrial fibrillation and arrhythmias

Vascular disorders: vasculitis and phlebitis

Gastrointestinal disorders: pancreatitis and dysphagia

Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders: dermatitis and petechiae

Musculoskeletal connective tissue and bone disorders: tendon rupture and tendinitis

Renal and urinary disorders: renal failure

General disorders and administration-site conditions: oedema

Table 1.

List of positive and negative control outcomes for ciprofloxacin and clarithromycin

| Ciprofloxacin | Clarithromycin | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive outcomes | Negative outcomes | Positive outcomes | Negative outcomes |

|

Thrombocythemia Pancytopenia Anaphylactic shock Intracranial hypertension Vertigo Gait disturbance Peripheral neuropathy Tinnitus Hearing loss Syncope Arrythmias Vasculitis Pancreatitis Petechiae Tendinitis Tendon rupture Renal failure Oedema |

Pneumonia Cellulitis Gastrointestinal bleeding Hip fracture |

Cellulitis Anaphylactic shock Vertigo Tinnitus Hearing loss Atrial fibrillation Arrythmias Phlebitis Pancreatitis Dermatitis Renal failure |

Thrombocythemia Pancytopenia Intracranial hypertension Amnesia Gait disturbance Peripheral neuropathy Transient vision loss Uveitis Gastrointestinal bleeding Petechiae Tendinitis Tendon rupture Hip fracture |

Discussion

There is a need to take into account characteristics of the study design to choose DOIs and HOIs to optimise the performance of drug safety signal detection studies. This can be done through the application of a taxonomy framework. The aim of this work was to describe such a framework, to outline the main general principles considered and to apply these for the selection of a reference set in a self-controlled signal detection study. This work was based on previous studies but tailored to our specific method-based approach and to the specificities of signal detection. The general principles can be applied to any method but specific implementation needs to be adapted depending on the chosen design.

Previous work from the Sentinel project, despite not being directly related to drug safety signal detection, provides a good basis. We used Sentinel principles as the foundation for our framework, by reviewing their criteria and including only those relevant to signal detection. We added an assessment of the suitability of the DOIs and HOIs in the database of interest, as it is necessary to make sure the study is feasible or to choose a database accordingly.

While there is a clear need to change the way reference sets are developed for a method evaluation based on the exposure and outcomes of interest as well as the data source, these must be clearly defined a priori. Explanation of the choice of reference set should be consistent and transparent, in line with the renewed focus on enhanced replicability and transparency in real-world evidence generation from healthcare databases [22].

Application of the Framework for the Selection of a Reference Set

Several criteria from the Sentinel project were reused either directly or indirectly regarding the study requirements: the exposure use pattern, the onset and duration of exposure risk window, and the degree of misclassification through the coverage in the database of interest. We did not consider the strength of within- and between-person confounding because in our study time-invariant confounding is handled by the self-controlled design, and part of the time-variant confounding is handled by the short observation period, and the use of active comparators. If between-person comparative methods are chosen, these would be important to be considered when selecting the DOIs and HOIs. By applying this taxonomy framework, we are able to utilise a single study design to investigate a very broad list of preselected HOIs, covering a range of organ classes and different levels of seriousness.

The Mini-Sentinel work recommended that when assumptions are met, self-controlled designs should be used in priority because within-person confounding is handled [23]. If assumptions are not met, an alternative design should be chosen. Our work provided an example of checking SCCS assumptions and an extension to accommodate active comparators.

Challenges in Implementing the Framework

Although we attempted to present the choice of criteria in a systematic approach, some criteria still relied on clinical opinion and human judgement to be implemented, introducing some degree of subjectivity in the process, which was highlighted when applying the framework to the case study. Importantly, our proposed framework encourages the systematic documentation of the decision-making process, which could lead to high transparency of signal detection-related research studies.

In the application of the framework for the reference set, the original number of adverse events in the label investigated was 273, but the final list contains only 28 outcomes after application of the framework. However, it must be recognised that not all adverse events listed in a product label are of equal public health importance, and that many outcomes were excluded from our reference set for reasons such as their mild self-limiting nature. Here, we have selected those that the assessors considered to be of highest public health importance, as well as those that are most suited to the constraints of the study. The reference set we obtained contains HOIs and DOIs appropriately covered in the CPRD. We have also checked that the final list of drugs and outcomes was also well covered in the other databases (Systeme National des Donnees de Sante and MarketScan) used in the study. This will enable the use of the same reference set in several nationwide databases, leading to multi-database comparisons of the results of this study.

There is a potential misclassification and imbalance between the number of positive and negative controls [24] in the reference set obtained. Indeed, labels do not necessarily represent true causal associations, and an outcome absent from the label could still be associated with a DOI if the association is unknown. We identified a much larger number of positive controls than negative controls, which was because of the strict criteria we chose to ensure the quality of the negative controls. More broadly, we recognise that routine signal detection within a RWD database should be considered one of many tools in the broader signal detection armoury, with unique strengths and limitations.

Adaptation of This Framework

This framework can be implemented at a broader scale in signal detection studies. Our work was method based (SCCS with active comparators as an example) but it is also possible to adapt a similar framework to drug- or outcome-based approaches, as well as to study designs other than SCCS. Depending on the drug(s) and/or outcome(s) of interest, their characteristics and coverage in the available database, one can choose the appropriate design and type of analysis. To apply our framework, a list of pre-specified outcomes of interest is needed. We selected the outcomes of interest based on drug labels, which is not necessarily useful when designing a non-performance assessment signal detection study. Further, there is no reason why this framework could not be applied to vaccine signal detection as well. Where a range of different drugs and outcomes are of interest that do not share characteristics amenable to a single study design, several study designs may need to be considered to optimise the potential for signal detection using routinely collected health data.

Conclusions

Here, we propose a framework for the optimal selection of HOIs and DOIs in signal detection studies given a chosen study design and have applied it to an example using the SCCS design with the novel active comparator method to assess its performance. This framework could also be used for investigating drug safety only, including other drug or vaccine outcome pairs, as well as for other study designs.

This framework will enable the evaluation of optimal method performance by removing outcomes from the investigation pool that are not suited to the method or database of choice, which we believe will promote better decision making about the choice of potential signal detection methods. This framework will be increasingly useful as signal detection in RWD becomes more prevalent and clarity on performance, in addition to issues like transparency, will be critical for trusted routine use. In future work, wide reference sets could be developed that one could easily use to pull the HOIs and DOIs of relevance for a given RWD signal detection study.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Laurie Tomlinson for helping with the review of the outcomes.

Declarations

Funding

Astrid Coste is funded by a GSK PhD studentship to undertake this work.

Conflicts of Interest/Competing Interests

Andrew Bate is an employee of GSK and holds stocks and stock options. However, Andrew Bate did not actively participate in the assessment of the labels and choice of outcomes for this methodological study. Ian J. Douglas holds grants and shares from GSK. GSK markets the following drugs: amoxicillin. Charlotte Warren-Gash is funded by a Wellcome Career Development Award (225868/Z/22/Z). Angel Wong and Julian Matthewman have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this article.

Ethics Approval

This study has been approved by the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine Ethics Committee (approval number 27650).

Consent to Participate

Not applicable, as no human or animal data were used to conduct this study.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable, as no human or animal data were used to conduct this study.

Availability of Data and Material

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Authors’ Contributions

AC, AW, AB and IJD have contributed to the design of the study. AC was responsible for conducting the study and drafting the manuscript, which has been reviewed by all co-authors. CWG and JM have contributed to the selection of the outcomes. All authors read and approved the final version.

References

- 1.Gruber S, Chakravarty A, Heckbert SR, Levenson M, Martin D, Nelson JC, et al. Design and analysis choices for safety surveillance evaluations need to be tuned to the specifics of the hypothesized drug-outcome association. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2016;25:973–981. doi: 10.1002/pds.4065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bate A, Hornbuckle K, Juhaeri J, Motsko SP, Reynolds RF. Hypothesis-free signal detection in healthcare databases: finding its value for pharmacovigilance. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2019;10:204209861986474. doi: 10.1177/2042098619864744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coste A, Wong A, Bokern M, Bate A, Douglas IJ. Methods for drug safety signal detection using routinely collected observational electronic health care data: a systematic review. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2023;32:28–43. doi: 10.1002/pds.5548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robb M, Behrman R, Racoosin J. Mini-Sentinel Coordinating Center Submission of Task Order 1 Deliverable: methods framework (taxonomy) for evaluating medical product safety (5.4.1). 2010.

- 5.Baker MA, Lieu TA, Li L, Hua W, Qiang Y, Kawai AT, et al. A vaccine study design selection framework for the postlicensure rapid immunization safety monitoring program. Am J Epidemiol. 2015;181:608–618. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwu322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cederholm S, Hill G, Star K, Noren GN, Asiimwe A, Bate A, et al. Structured assessment for prospective identification of potential safety signals in electronic health records. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2014;23:417. doi: 10.1007/s40264-014-0251-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ryan PB, Madigan D, Stang PE, Marc Overhage J, Racoosin JA, Hartzema AG, et al. Empirical assessment of methods for risk identification in healthcare data: results from the experiments of the Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership. Stat Med. 2012;31:4401–4415. doi: 10.1002/sim.5620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schuemie MJ, Gini R, Coloma PM, Straatman H, Herings RMCC, Pedersen L, et al. Replication of the OMOP experiment in Europe: evaluating methods for risk identification in electronic health record databases. Drug Saf. 2013;36:159–169. doi: 10.1007/s40264-013-0109-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sturkenboom MCJM, Van Der Lei J, Trifiro G, Fourrier-Reglat A, Acedo CD. The EU-ADR project: preliminary results and perspective. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2009;148:43–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gagne JJ, Baker M, Bykov K, Kawai AT, Yih K, Lee G, et al. Mini-sentinel methods development of the mini-sentinel taxonomy prompt selection tool: year three report of the Mini-Sentinel Taxonomy Project Workgroup. 2013.

- 11.Suchard MA, Zorych I, Simpson SE, Madigan D, Schuemie MJ, Ryan PB. Empirical performance of the self-controlled case series design: lessons for developing a risk identification and analysis system. Drug Saf. 2013;36:S83–93. doi: 10.1007/s40264-013-0100-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hallas J, Whitaker H, Delaney JA, Cadarette SM, Pratt N, Maclure M. The use of active comparators in self-controlled designs. Am J Epidemiol. 2021;190:2181–2187. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwab110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pouwels KB, Hopkins S, Llewelyn MJ, Walker AS, McNulty CA, Robotham JV. Duration of antibiotic treatment for common infections in English primary care: cross sectional analysis and comparison with guidelines. BMJ. 2019;364:I440. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wong AYS, Root A, Douglas IJ, Chui CSL, Chan EW, Ghebremichael-Weldeselassie Y, et al. Cardiovascular outcomes associated with use of clarithromycin: population based study. BMJ. 2016;352:h6926. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h6926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sandhu HS, Brucker AJ, Ma L, VanderBeek BL. Oral fluoroquinolones and the risk of uveitis. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016;134:38–43. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2015.4092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ray WA, Murray KT, Hall K, Arbogast PG, Michael SC. Azithromycin and the risk of cardiovascular death. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1881–1890. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crellin E, Mansfield KE, Leyrat C, Nitsch D, Douglas IJ, Root A, et al. Trimethoprim use for urinary tract infection and risk of adverse outcomes in older patients: cohort study. BMJ. 2018;360:k341. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thurin NH, Lassalle R, Schuemie M, Pénichon M, Gagne JJ, Rassen JA, et al. Empirical assessment of case-based methods for identification of drugs associated with acute liver injury in the French National Healthcare System database (SNDS) Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2021;30:320–333. doi: 10.1002/pds.5161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xiaofeng Z, Douglas IJ, Shen R, Bate A. Signal detection for recently approved products: adapting and evaluating self-controlled case series method using a US claims and UK electronic medical records database. Drug Saf. 2018;41:523–536. doi: 10.1007/s40264-017-0626-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Whitaker HJ, Ghebremichael-Weldeselassie Y, Douglas IJ, Smeeth L, Farrington CP. Investigating the assumptions of the self-controlled case series method. Stat Med. 2018;37:643–658. doi: 10.1002/sim.7536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thurin NH, Lassalle R, Schuemie M, Pénichon M, Gagne JJ, Rassen JA, et al. Empirical assessment of case-based methods for identification of drugs associated with upper gastrointestinal bleeding in the French National Healthcare System database (SNDS) Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2020;29:890–903. doi: 10.1002/pds.5038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang SV, Sreedhara SK, Schneeweiss S, Franklin JM, Gagne JJ, Huybrechts KF, et al. Reproducibility of real-world evidence studies using clinical practice data to inform regulatory and coverage decisions. Nat Commun. 2022;13:5126. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-32310-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gagne JJ, Nelson JC, Fireman B, Seeger JD, Toh D, Gerhard T, et al. Mini-sentinel methods taxonomy for monitoring methods within a medical product safter surveillance system: year two report of the Mini-Sentinel Taxonomy Project Workgroup. 2012.

- 24.Hauben M, Aronson JK, Ferner RE. Evidence of misclassification of drug–event associations classified as gold standard ‘negative controls’ by the Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership (OMOP) Drug Saf. 2016;39:421–432. doi: 10.1007/s40264-016-0392-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.