Abstract

Sexual arousal plays an important role in condom use decisions. However, combined effects of reduced sexual arousal and delay to achieving arousal on condom use decisions remains understudied. This study used a novel sexual arousal-delay discounting (SADD) task to measure individuals’ willingness to use a condom in situations where condom use would (1) delay time to arousal and (2) reduce the level of arousal one could achieve even after the delay (e.g., 5 minutes to reach 50% arousal). In Study 1, U.S. college students (N=115; Mage=18.6) reported their willingness to have sex with a condom in hypothetical scenarios where the condom delayed and reduced their partner’s sexual arousal. In Study 2, U.S. college students (N=208; Mage=19.6; 99% ≤ 24 years old) completed the same task for two partners–partner perceived as most desirable and partner perceived as least likely to have an STI. In this study, a condom would affect either participants’ own or partner’s arousal. Study 3 replicated Study 2 using a non-college sample in the U.S. (N=227; Mage=30.5; 84% ≥ 25 years old). Across studies, willingness to use a condom decreased as the delay to reduced arousal increased. This effect of SADD was stronger when condoms reduced participants’ own (vs. partner’s) arousal, whereas comparisons between most desirable and least likely-to-have-STI partners provided mixed findings. Men had higher discounting rates than women across conditions. Greater SADD was associated with lower condom use self-efficacy, providing initial evidence for the task’s validity. The role of delayed arousal in condom use and implications are discussed.

Keywords: Sexual discounting, delay, arousal, partner desirability, perceived STI risks, STI, HIV, condom use

Recent behavioral research has seen a growing use of hypothetical tasks to measure decision-making processes underlying health behaviors. Delay discounting – the subjective devaluation of an outcome as a function of the delay until receiving that outcome (Green & Myerson, 2004) – is one such process. In typical delay discounting studies, participants make a series of hypothetical choices between a smaller reward delivered sooner (i.e., smaller-sooner) versus a larger reward delivered later (i.e., larger-later), from which an index of delay discounting can be calculated (Amlung et al., 2019). The discounting index derived from such tasks is conceptualized as a measure of individuals’ pattern of preferences for immediate rewards over delayed gratification (Amlung et al., 2019). Steeper delay discounting is associated with various health behaviors and outcomes, including psychiatric disorders (Amlung et al., 2019), substance misuse (Bickel et al., 2014; Strickland et al., 2021), avoidance of medical screening, including HIV/STI testing (Wongsomboon & Shepperd, 2022; Wongsomboon & Webster, 2023), and obesity (Bickel et al., 2021). Taken together, evidence supports the delay discounting phenomenon and highlights the utility of hypothetical tasks in understanding decision making related to behaviors of public health import.

Further evidence also suggests that delay discounting is domain specific, such that stronger discounting effects are observed when relevant rewards (vs. money) are measured. For instance, individuals’ percent body fat was more strongly associated with discounting of hypothetical food (i.e., smaller bites of favorite food available immediately vs. bigger bites available later) compared to discounting of hypothetical money (Rasmussen et al., 2010). Relevant to sexual behaviors, robust evidence now shows strong support for sexual delay discounting – an index of sexual choice and behavior measured in several ways, including duration, frequency, and quality of sex (for a review, see Johnson et al., 2021). Among them, the most widely studied phenomenon is discounting of condom-protected sex (Johnson & Bruner, 2012). Studies consistently show that people are less likely or willing to have sex with a condom (i.e., sexual discounting) when condom availability is delayed; however, the degree of sexual discounting can vary based on levels of partner desirability and perceived risks of STI transmission (Gebru et al., 2022; Johnson et al., 2021). Additionally, greater sexual discounting is associated with self-reported sexual risk behaviors, such as condomless sex (Herrmann et al., 2015; Johnson & Bruner, 2012). These findings have been replicated in several populations with varying degrees of risks for HIV/STI (e.g., college students, men who have sex with men, people who use substances; Gebru et al., 2022).

In addition to the delay to condom availability, anticipated reduction in sexual arousal resulting from condom use may also affect individuals’ condom use decisions. Indeed, research shows that one of the main reasons for condom non-use is reduced pleasure (Crosby et al., 2008; Fennell, 2014; Higgins & Wang, 2015). Although past research has demonstrated the role of arousal in sexual behavior and decision-making, little research has examined arousal in relation to discounting processes. Wongsomboon and Cox (2021) were the first to examine sexual arousal discounting–the systematic reduction in willingness to engage in condom-protected sex as a function of reduced arousal due to condom use.

In the sexual arousal discounting task (Wongsomboon & Cox, 2021), participants rated their willingness (from 0 to 100) to use a condom when the condom would decrease either (1) their own arousal or (2) their partner’s arousal (between-persons). Participants had an option between partially aroused, condom-protected sex (e.g., 50% aroused if having sex with a condom) and fully aroused, condomless sex (100% aroused if having sex without a condom). Results showed that people’s willingness to have condom-protected sex decreased as sexual arousal decreased due to condom use. Further, the degree of discounting was higher when the condom affected their own (vs. partner’s) arousal, though this was true only with the partner low in perceived desirability. Additionally, the amount of discounting measured by this task was shown to predict criterion measures of sexual risk-taking, including condom use self-efficacy and past behavior, suggesting good validity of the task (Wongsomboon & Cox, 2021). However, their study only examined the impact of reduced arousal on condom use decisions, not the effect of delay to experiencing that arousal.

To summarize, robust literature supports the role of delay and sexual arousal in understanding sexual behaviors, particularly condom use. Following this, ample research has now established many variations of the sexual discounting framework, including sexual delay discounting and sexual arousal discounting. However, the incremental effects of delay and arousal remain unknown. In the real-world, it is likely that a combination of different factors influence condom use decisions.

Overview

The current study extends past research by testing how delay and arousal together impact condom use decisions. Specifically, we examined how people’s reported willingness to use a condom was influenced by (1) decreased level of arousal and (2) increased delay to achieving that level of arousal. The aim was to examine the effects of sexual arousal and delay (and the combination of both) on condom use decisions.

To achieve this aim, we developed a novel hypothetical discounting task called Sexual Arousal-Delay Discounting (SADD) Task. This task simulated aspects of common real-life sexual encounters in which applying a condom creates arousal-related problems (Graham et al., 2006; Sanders et al., 2015). For instance, an individual may experience difficulties getting an erection or sexual arousal (for women) in a timely manner when using a condom, and even after the delay, still be unable to reach full erection/sexual arousal. In other words, the SADD task assessed the impact of the delay to reduced arousal on reported willingness to use condoms. Our first hypothesis is that people’s willingness to have condom-protected sex would decrease as a function of the delay to sexual arousal. We also expected that this effect of delay would be even stronger when the sexual arousal was reduced (e.g., 50% vs. 100% arousal) due to condom use.

Across three online experimental studies, we examined people’s willingness to use a condom given that (a) the condom reduced arousal levels and (b) the time it took to reach that arousal level (i.e., delay to arousal) varied. In Study 1, we developed the SADD task and initially tested it among college students. In this task (a 6 [arousal] × 5 [delays to arousal] within-persons design), participants were presented with a hypothetical scenario in which a condom would affect their partner’s sexual arousal (vs. 100% aroused if not using a condom). Participants then reported their willingness to use a condom on a 0–100 visual analog scale for each condition. Each person was presented with 6 arousal conditions (100%, 90%, 75%, 50%, 25%, 10%), presented in a descending order. They also completed 5 delay conditions (5 mins, 15 mins, 30 mins, 1 hour, 3 hours; presented in an ascending order) in which the partner would need the specified delay to reach the specified amount of arousal if using a condom (e.g., 30 minutes until 50% arousal).

Study 2 was a 2 [own vs. partner’s arousal] × 3 [arousal] × 6 [delays to arousal] between-within-persons design. College students completed the SADD task reporting their willingness to have sex with a condom when either (1) their own or (2) their partners’ arousal levels decreased due to condom use (between-persons). Each participant was presented with 3 arousal levels (100%, 50%, 10%; within-persons) that could be achieved after 6 delays (0 delay, 5 mins, 15 mins, 30 mins, 1 hour, 3 hours; within-persons). Note that the first two studies focused on college students, or young adults broadly, because they are at relatively high risk for HIV/STI. Specifically, young adults ages 15–24 years old account for half or more than half of new HIV/STI infections in the United States (CDC, 2021, 2022). Next, we added Study 3 to see if results would be replicated in a broader, more general sample – namely, adults in a non-college setting (age = 19–42, Mage = 30.5; 84% ≥ 25 years old).

Because sexual discounting is found to be context-dependent (Johnson et al., 2021, Wongsomboon & Cox, 2021), Studies 2 and 3 manipulated partner characteristics (partner desirability and perceived STI risks) and target of reduced arousal (self vs. partner). We hypothesized that the rate of discounting would be higher when condoms affected one’s own (vs. partner’s) arousal. Further, as previous research suggests that partner desirability (vs. perceived STI risk) may have a bigger influence on sexual discounting (Wongsomboon & Robles, 2017), we also hypothesized that participants would display higher discounting when having sex with the most desirable partner than with the partner least likely to have an STI. Lastly, for exploratory purposes, we examined gender differences in discounting on the SADD task. Given previous research with the sexual delay discounting task (Gebru et al., 2022), we expected that overall, men would have higher discounting rates than women.

Given the task’s novelty, we tested the correlation between discounting as measured by this SADD task and an indicator of condom use behavior – condom use self-efficacy, defined as individuals’ confidence in using a condom across various situations (Farmer & Meston, 2006; Oppong Asante et al., 2016). A significant correlation between discounting rates and reported condom use self-efficacy would provide preliminary evidence for the construct and criterion validity of the SADD task. Specifically, we hypothesized that the steeper discounting measured by the SADD task would be correlated with lower levels of condom use self-efficacy.

Study 1

The aim of Study 1 was to develop the SADD task and test how degrees of delay discounting differed among different arousal levels. We also aimed to examine whether and how SADD correlated with condom use self-efficacy.

Method

Participants

Participants were college students at a large public university in the Southeastern U.S. who received research credits for an introductory psychology class for their participation. Data were collected between July and August 2019. After data exclusion (see details in the Procedure and Data Analysis sections), the final sample was 115 participants (Mage = 18.60, SD = 0.85; range 18 to 21 years; 65.2% female). Similar to other sexual discounting studies (e.g., Wongsomboon & Cox, 2021), women who were exclusively interested in women were not eligible to participate because the present study focused solely on male condom use. The majority of the sample identified as heterosexual (84.3%), with the rest of the sample consisting of bisexual (12.2%), gay (2.6%) and other sexual orientations not on the list (0.9%). The sample was 45.2% European White, 20.0% Hispanic/Latino, 15.7% Asian, 12.2% Black, 1.7% Middle Eastern, 0.9% Native American, and 3.5% other races not on the list. Most participants (62.3%) reported having had experience of sexual intercourse.

Procedure and Measures

The study occurred entirely online. All procedures were carried out using the Qualtrics survey platform and approved by the university’s Institutional Review Broad. All supplemental materials, including instructions and items, in Studies 1–3 are provided verbatim here: https://osf.io/4vkeh/?view_only=4841eb351d0e4aa29c6a35ad614ec4ea.

Partner selection.

Participants were asked to imagine being single and available if they were currently in a relationship. Then, from a pool of pictures, they selected one partner with whom they most wanted to have sex. Female participants saw 20 pictures of only men. Male participants reporting sexual attraction to women saw 20 pictures of women. Male participants reporting sexual attraction to men saw 20 pictures of men. Male participants reporting sexual attraction to any genders saw 40 pictures–20 men and 20 women. Five participants (all female) were automatically excluded from the study as they indicated not wanting to have sex with any of the available partners under any circumstances.

Sexual arousal-delay discounting (SADD) task.

Sexual arousal in this study was explicitly defined to participants as the “physiological responses that occur in the body and mind such as nipple hardening, erection of penis or clitoris, and vaginal lubrication.” Following previous research (e.g., Wongsomboon & Cox, 2021), participants were asked to imagine that they and their partner (who they just met for the first time at a social event) were in the mood for sex and that effective birth control methods (e.g., IUD) were in place. Each person was presented with 6 arousal conditions (100%, 90%, 75%, 50%, 25%, 10%), presented in a descending order. In the full-arousal trial (100%), the first (baseline) item indicated that their partner would be 100% aroused immediately with or without a condom (“100% arousal, no delay”). Participants then rated their willingness to have condom-protected sex with that partner (from 0 to 100 where 0 was “I would definitely have sex without a condom” and 100 was “I would definitely have sex with a condom”).

After the first item (but still within the full-arousal trial), participants then rated their willingness to have condom-protected sex if using a condom would add a delay to achieving arousal. That is, their partner would be “100% sexually aroused in [delay duration] with a condom” or “100% sexually aroused immediately without a condom.” Five different delay durations were used, presented in ascending order, from 5 minutes, 15 minutes, 30 minutes, 1 hour, to 3 hours. In other words, participants reported their willingness to use a condom if using a condom would add a specified delay duration for the partner to reach this level of arousal (e.g., “100% sexually aroused in 5 minutes with a condom” vs. “100% sexually aroused immediately without a condom).

After participants completed all five delay items for the full-arousal trial (i.e., 100% arousal after delays), they proceeded to the partial-arousal trials in which using a condom would decrease their partner’s levels of sexual arousal (i.e., 90%, 75%, 50%, 25%, and 10% arousal levels). For example, after the 100% arousal trial, participants were told that this time their partner’s arousal level would be 90% with a condom (without a condom, the partner would always be 100% aroused immediately). In other words, participants had a choice between partially-aroused, condom-protected sex versus fully-aroused, condomless sex. They were informed that their partner could still have sexual intercourse regardless of levels of sexual arousal, though reduced arousal might have an impact on sexual pleasure and/or quality of sex.

Participants answered the same set of delay items with all five arousal levels (90%, 75%, 50%, 25%, 10%) for condom-protected sex (in a descending order). That is, within the same arousal level, the delay items repeated five times (from 5 minutes to 3 hours). Unlike the 100% arousal trial that started with no delay (i.e., the partner was fully aroused immediately with or without a condom), all other arousal trials did not have the no-delay item (i.e., the questions always started with the shortest delay, which is 5 minutes, if using a condom).

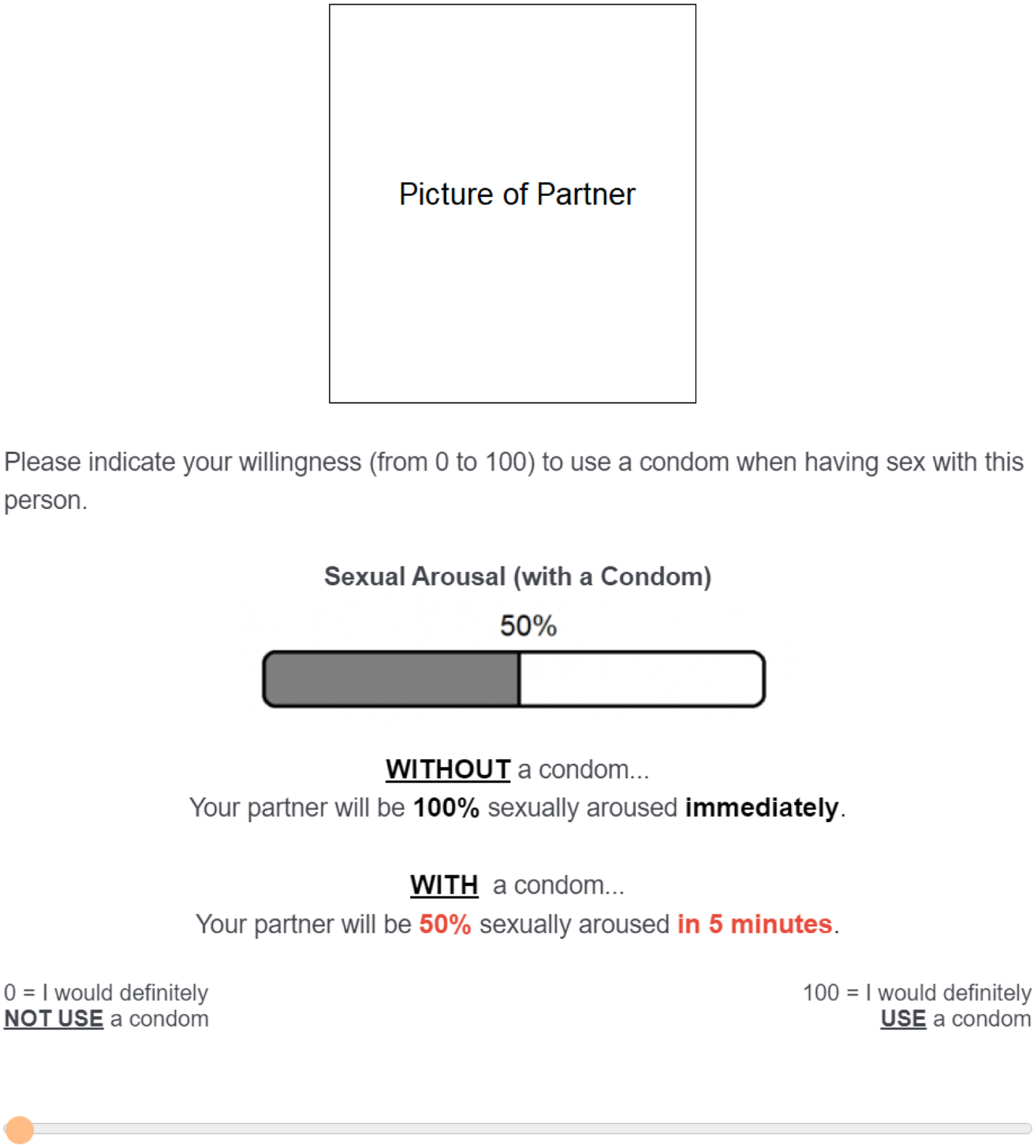

In summary, in addition to the first baseline item (100% arousal, no delay), participants completed a total of 6 (arousal: 100%, 90%, 75%, 50%, 25%, 10%) × 5 (delay: 5 minutes, 15 minutes, 30 minutes, 1 hour, 3 hours) items. For illustration purposes, Figure 1 shows one sample item (5 minutes delay) from the 50% arousal trial.

Figure 1.

Sample item from the Sexual Arousal Delay Discounting (SADD) Task. For each of the six arousal trials (100%, 90%, 75%, 50%, 25%, 10%), participants completed five delay items (5 minutes, 15 minutes, 30 minutes, 1 hour, 3 hours) associated with that arousal level. This figure depicts the condition in which using a condom would result in a 5-minutes delay to reaching a 50% arousal level. A picture of participants’ selected partner was shown in every item.

Condom use self-efficacy.

The Self-Efficacy for Condom Use Scale (Mausbach et al., 2007) is a previously validated 9-item measure asking participants to rate their confidence in using a condom on a 4-point scale (1 = strongly disagree and 4 = strongly agree). Example items included: “I can use a condom properly,” “I can use a condom every time I have penetrative sex,” and “I can use a condom in any situation.” We averaged all items to get a composite score (M = 3.28, SD = 0.46). Higher scores indicated higher self-efficacy (α = .86).

Data analysis

To assess the extent to which the delay to achieving a certain amount of sexual arousal reduced participants’ reported willingness to use a condom (i.e., degree of discounting), we calculated area under the discounting curve (AUC; Myerson et al., 2001) for each arousal trial (six AUCs total). For each set of arousal trials (e.g., 50% arousal), the raw willingness ratings were standardized for each participant. This is done by dividing the reported willingness to use a condom at each delay (e.g., 5 minutes to 50% arousal) by the reported willingness to use a condom at the baseline (100% arousal, no delay)1. This data transformation results in standardized AUC values ranging from 0 to 1, with lower AUC indicating higher discounting (i.e., delay had a greater influence on reported willingness to use a condom).

Participants who reported zero willingness to use a condom at the baseline would be removed from the analysis because their data were undefined after standardization (no such case in this study). Data were flagged as potentially nonsystematic if (1) the condom use rating at a given delay exceeded the immediately preceding rating by more than 0.2, or (2) the rating at the longest delay (3 hours) exceeded the rating when a condom was immediately available by more than 0.1 (Johnson et al., 2015; Johnson & Bickel, 2008). Seven participants had two or more points that met nonsystematic criteria in at least half of the trials, and thus were removed from the analysis.

First, we ran a sensitivity analysis to test the difference in all AUCs between sexually experienced and inexperienced participants. The two groups did not differ in discounting rates and thus were analyzed together as a whole. We ran a non-parametric Friedman test to compare differences in AUC among each of the six arousal trials. We also ran separate simple regressions (5,000 bootstrap samples with 95% bias corrected) to test the relationships between each of the six AUCs and condom use self-efficacy.

Results

Figure 2 illustrates the discounting patterns from each arousal trial. Results from the Friedman test showed a statistically significant difference among the six arousal trials, χ2(5) = 210.54, p < .001. The 10% arousal trial had lower AUC (higher discounting) (Mdn = 0.19) than all other trials (ps ≤ .001) except the 25% arousal trial. The 25% arousal trial had lower AUC (Mdn = 0.29) than the 100%, 90%, and 75% arousal trials (ps < .001). The 50% arousal trial had lower AUC (Mdn = 0.51) than the 100% and 90% trials (ps < .001). The 75% arousal trial had lower AUC (Mdn = 0.59) than the 90% arousal trial (p = .005). There was no statistically significant difference between the 90% (Mdn = 0.70) and 100% arousal trials (Mdn = 0.66). Significance values were adjusted by the Bonferroni correction for multiple tests.

Figure 2.

Raw reported willingness to use a condom (median) from Study 1.

In addition, results showed that AUCs from all arousal trials were positively related to condom use self-efficacy (r = .31 for the 100% arousal, r = .37 for the 90% arousal, r = .39 for the 75% arousal, r = .36 for the 50% arousal, r = .31 for the 25% arousal, and r = .30 for the 10% arousal; ps ≤ .01).

Discussion

Our results extend the previous research (Wongsomboon & Cox, 2021) by showing that individuals’ willingness to wait for condom-protected sex also decreases as a function of delay to sexual arousal. Although we observed delay discounting patterns in all arousal levels, the degrees of discounting were higher in the low arousal levels (e.g., 10–50% arousal) compared to the high arousal levels (e.g., 100% arousal). In sum, people tend to discount condom-protected sex when condom use delays sexual arousal. This effect of delay was even stronger if the condom reduces sexual arousal to a greater extent (e.g., 10% vs. 50%). Finally, we found that higher discounting (lower AUC) from all arousal levels was associated with lower reported condom use self-efficacy.

Study 1 had some limitations. First, all arousal trials used the same baseline (100% arousal, no delay) as a reference point. This means that other arousal levels (e.g., 50%) did not have their own no-delay baseline (e.g., being 50% aroused immediately with or without a condom). Second, past research has already shown that people may discount condom-protected sex more when a condom affects their own arousal (Wongsomboon & Cox, 2021). However, Study 1 only assessed the effect of condoms on partner’s arousal. Third, Study 1 only included the partner with whom participants ‘most wanted to have sex’ (i.e., most desirable). However, other partner characteristics besides desirability or attractiveness (e.g., perceived STI risk) can also influence degrees of discounting (Wongsomboon & Cox, 2021; Wongsomboon & Robles, 2017). All these limitations were addressed in Studies 2 and 3.

Study 2

For simplicity reasons, Study 2 used only three arousal levels: 100%, 50%, and 10%. These arousal levels statistically differed in terms of the degree of discounting in Study 1 and made the most intuitive sense (full vs. half vs. low arousal). In this study, participants were randomized into one of the two groups (between-persons). A condom would reduce their own arousal in one group (“self-arousal”) or their partner’s arousal in another group (“partner-arousal”). In addition, each participant completed the same set of discounting tasks for two partners: the partner with whom they most wanted to have sex (“most desirable”) and the partner they perceived as least likely to have an STI (“least STI”; within-persons). We specifically used these two partner categories because they usually elicited relatively high discounting in previous studies (Johnson et al., 2021). For exploratory purposes, we examined potential gender differences in discounting rates. All other procedures remained the same as in Study 1.

Method

Participants

Participants were college students at a large public university in the Southeastern U.S. who participated in exchange for research credits as part of an introductory psychology class. Data were collected between March and August 2020. After data exclusion (see details in the Procedure and Data Analysis sections), the final sample was 208 participants (Mage = 19.56, SD = 2.68; range 18 to 53 years; 99% ≤ 24 years old; 52.4% female). The majority identified as heterosexual (88%), with the rest of the sample consisting of bisexual (9.1%), gay (men; 1%) and other sexual orientations not on the list (1%). Half of the sample (50%) were European White. The rest consisted of 23.6% Hispanic/Latino, 11.5% Asian, 9.6% Black, 1.4% Middle Eastern, 1% Biracial/Multiracial, and 1.9% other race not on the list. Most participants (68.8%) reported having had experience of sexual intercourse.

Procedure and Measures

Partner selection.

The pictures for partner selection were the same as in Study 1. Unlike Study 1, participants began by excluding anyone with whom they would never want to have sex under any circumstance. Next, they confirmed that the remaining, non-excluded pictures depicted people they might have sex with in at least some situations. Participants could exclude as many pictures as they wanted (or even none). However, unknown to the participants, the study would end if they did not select at least two potential partners (n = 10; 8 were female).

From the remaining pictures, participants selected one person with whom they most wanted to have sex (the most desirable partner) and one person they perceived as least likely to have an STI (the least STI partner). The two selected pictures became their hypothetical sexual partners for the SADD task. For direct statistical comparisons between the two partner categories, participants who selected the same picture for both (n = 54) were excluded.

SADD task and condom use self-efficacy.

The SADD task was the same as in Study 1 with some exceptions. First, a condom in Study 1 only decreased a partner’s sexual arousal. In this study, using a condom would decrease participants’ own arousal in one group (the self-arousal group) or their partner’s arousal in the other group (the partner-arousal group). To control for individual differences in past experience with condom use, participants in the self-arousal group also imagined that their sexual arousal in this particular scenario was affected by condom use regardless of their real experience with condoms in the past. Second, participants completed the same SADD task twice for the two partners (most desirable and least STI; in random order). Third, there were only three arousal trials in this study (vs six in Study 1). Fourth, we added a no-delay item for all arousal trials. Specifically, the first questions of the 50% arousal and 10% arousal trials now provided the scenario in which participants (or their partner) could achieve the specified amount of arousal immediately when using condoms (e.g., 50% aroused immediately with a condom vs. 100% aroused immediately without a condom). Finally, condom use self-efficacy was measured using the same scale as in Study 1. Again, we averaged all items to get a composite score (M = 3.36, SD = 0.50), with higher scores indicating higher self-efficacy (α = .87).

Data Analysis

AUC was calculated using the same method as in Study 1. However, unlike Study 1 in which raw condom use ratings from all arousal trials were divided by the rating from the ‘100% aroused, no delay’ condition (the baseline item), in Study 2 raw ratings from each of the three arousal trials (e.g., 50% aroused after X delay with a condom) were divided by the rating from the no-delay item of its respective trial (e.g., 50% aroused immediately with a condom). Each participant had a total of six AUC scores (2 partners × 3 arousal levels).

Some participants reported zero willingness to use a condom at the baseline (no delay) of each trial2. These participants were removed from the analysis for that specific partner because of undefined data after standardization (i.e., the denominator was zero). Further, of the datasets that were flagged as potentially nonsystematic (3%), 18 were removed because they had two or more points that met nonsystematic criteria. Three participants had nonsystematic data in at least half of the trials, and thus were removed entirely from the analysis.

Within each arousal trial, we used the Wilcoxon test to examine the differences in AUC between the most-desirable and least-STI partners. In addition, we used the Mann–Whitney U test to examine (1) the differences in AUC between the self-arousal group and the partner-arousal group and (2) gender differences in the overall AUC. Because the gender difference analyses were exploratory, for parsimony reasons, we combined AUCs across all arousal trials (i.e., 10%, 50%, and 100%) for each partner condition.

Note that we found a significant difference in AUC between sexually experienced and inexperienced participants in the 100% arousal trials of both partner conditions. Compared to those with no experience in sexual intercourse, participants with experience in sexual intercourse had lower AUC in the most-desirable partner condition (Mdn = 0.72 vs. 0.92; p = .038) and least-STI partner condition (Mdn = 0.69 vs. 0.93; p = .026), but only when the arousal level was 100%. Thus, analyses that included 100% arousal trials were conducted separately – one for those with sexual experience and one for those without. Nevertheless, results remained the same for both groups, and thus they were analyzed as a whole in the main analysis.

Finally, we ran separate simple regressions (5,000 bootstrap samples with 95% bias corrected) to test the relationships between each of the six AUCs and condom use self-efficacy.

Results

Figure 3 illustrates the discounting patterns from the three arousal trials (100%, 50%, 10%) for the two partners (most desirable and least STI).

Figure 3.

Raw reported willingness to use a condom (median) from Study 2. The left panel shows the ratings for the most desirable partner (i.e., the partner with whom they most wanted to have sex). The right panel shows the ratings for the least STI partner (i.e., the partner perceived as least likely to have an STI).

Difference between partner conditions.

Within the 100% arousal trial, there was no statistically significant difference between the most-desirable (Mdn = 0.80) and the least-STI partner conditions (Mdn = 0.79, p = .458). Within the 50% arousal trial, the most-desirable partner condition (Mdn = 0.79) had lower AUC (higher discounting) than the least-STI partner condition (Mdn = 0.85, z = 2.91, p = .004). Likewise, within the 10% arousal trial, the most-desirable partner condition (Mdn = 0.91) had lower AUC (higher discounting) than the least-STI partner condition (Mdn = 0.97, z = 2.40, p = .017).

Difference between arousal targets.

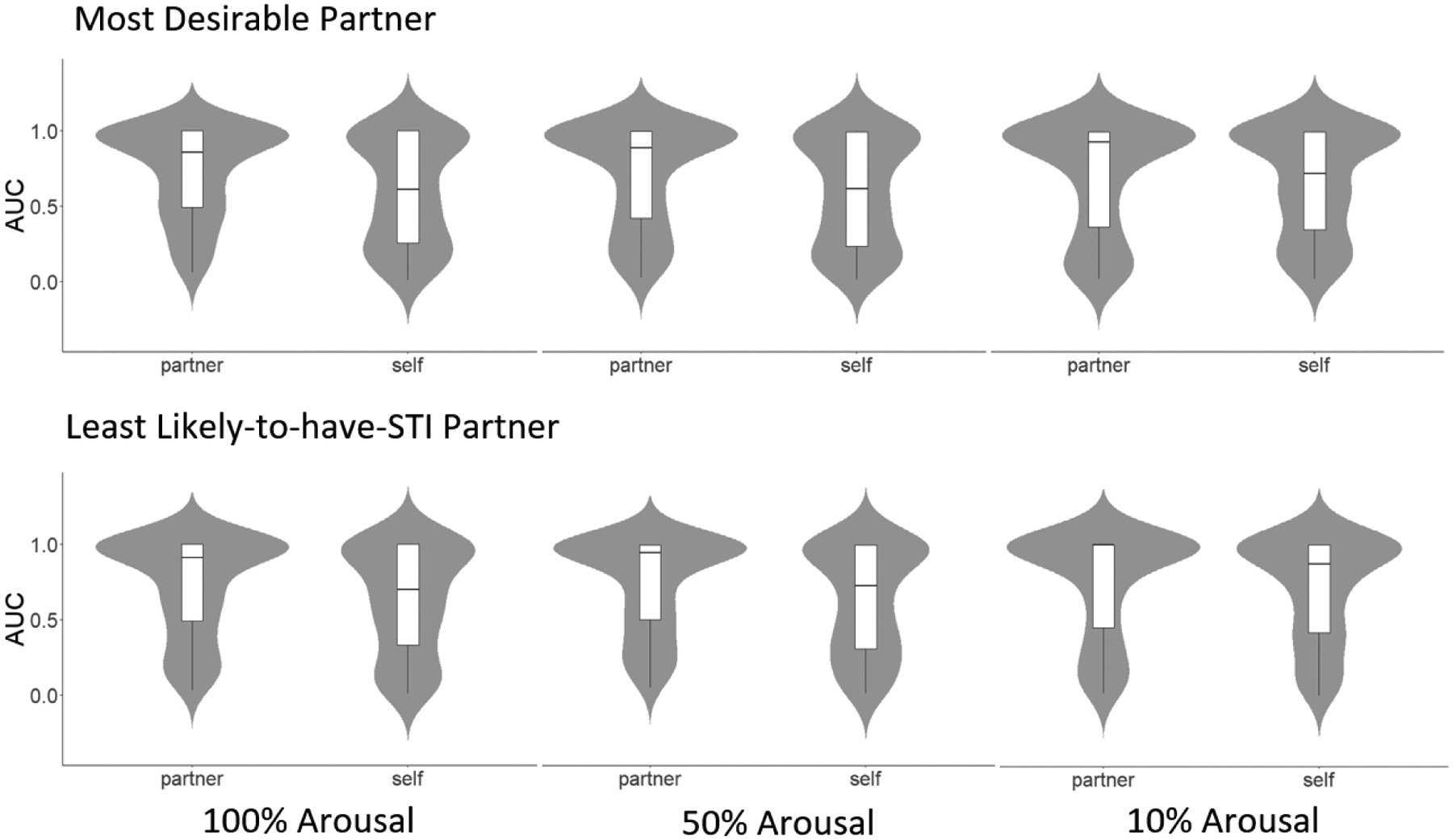

Figure 4 shows the AUCs from the self-arousal and partner-arousal groups in each of the three arousal levels and two partner conditions. Results showed that, in the most desirable condition, the self-arousal group (Mdn = 0.61) had lower AUC than the partner-arousal group (Mdn = 0.86) in the 100% arousal trial (U = 5,282, z = 2.57, p = .010). Similarly, the self-arousal group (Mdn = 0.62) had lower AUC than the partner-arousal group (Mdn = 0.89) in the 50% arousal trial (U = 5,323, z = 2.44, p = .015). However, there were no significant differences in AUC between the self-arousal (Mdn = 0.72) and partner-arousal groups (Mdn = 0.93) in the 10% arousal trial (p = .449).

Figure 4.

Violin plots showing AUCs from the partner-arousal group and the self-arousal group (Study 2). The upper panel represents the most desirable partner, and the lower panel represents the least STI partner. The x-axis shows each of the three arousal levels (from left to right): 100%, 50%, and 10%. The width of each curve of the violin plot corresponds with the approximate frequency of data points in each region. Within each violin plot resides a box plot; the first quartile marks one end of the box and the third quartile marks the other end of the box. The horizontal line inside the box represents the median. The whisker line extends from the end of the box to the minimum value. AUC = area under the discounting curve (ranging from 0 to 1). Lower AUC = higher discounting.

In the least-STI partner condition, the self-arousal group (Mdn = 0.70) had lower AUC than the partner-arousal group (Mdn = 0.91) in the 100% arousal trial (U = 5,578, z = 2.25, p = .025). Similarly, the self-arousal group (Mdn = 0.73) had lower AUC than the partner-arousal group (Mdn = 0.95) in the 50% arousal trial (U = 5,467, z = 2.28, p = .023). However, there was no significant differences in AUC between the self-arousal (Mdn = 0.88) and partner-arousal groups (Mdn = 1.00) in the 10% arousal trial (p = .253).

Difference between genders.

Men had lower overall AUC than women in both most-desirable partner (Mdn = 0.60 vs. 0.84; U = 5,710, z = 2.19, p = .029) and least-STI partner conditions (Mdn = 0.69 vs. 0.83; U = 5,732, z = 2.14, p = .032). To further explore if these gender differences existed in both self-arousal and partner-arousal groups, we did separate tests for each. Results showed that similar gender differences existed (i.e., men discounted more than women) in the self-arousal group (p = .008 for the most-desirable-partner AUC; p = .003 for the least-STI-partner AUC) but not in the partner-arousal group (p = .604 for the most-desirable-partner AUC; p = .802 for the least-STI-partner AUC). Figure 5 illustrates gender differences by partner conditions and arousal-target groups.

Figure 5.

AUCs separated by genders, partner conditions, and arousal target groups (Study 2). AUC = area under the discounting curve (ranging from 0 to 1). Lower AUC = higher discounting.

Relationship with condom use self-efficacy.

For the most-desirable partner condition, results from the Friedman test showed no statistically significant difference between the 100% and 50% arousal levels (p = .308). Thus, we averaged the AUCs from the two arousal levels (“higher arousal”). The AUC from the 10% arousal level (“lower arousal”) significantly differed from that of the 100% arousal (p = .008), and thus was retained for the analysis. Results showed that the mean AUC from the higher arousal levels was positively related to condom use self-efficacy (r = .30, p < .001). The AUC from the lower arousal level was also positively related to condom use self-efficacy (r = .22, p = .003).

For the least-STI partner condition, due to a lack of statistically significant differences, we averaged the AUCs from the three arousal levels (ps ranging from .295 to 1.00). Results showed that the mean AUC from the three arousal levels was positively related to condom use self-efficacy (r = .32, p < .001).

Discussion

Results from Study 2 extend those from the prior study by showing that the degree of discounting measured by the SADD task may also vary depending on contextual factors, such as partner characteristics and whose arousal is affected. Specifically, when arousal level was not affected by condom use (100%), participants discounted delayed-arousal, condom-protected sex similarly between the most desirable and least STI partners. However, when the arousal was reduced (50% and 10%) due to condom use, participants discounted delayed-arousal, condom-protected sex more for the highly desirable partner than for the one perceived as having low risk of STIs. Consistent with Study 1, higher degrees of discounting (regardless of arousal levels) in both partner conditions were associated with lower condom use self-efficacy.

In both most-desirable and least-STI partner conditions, participants in the self-arousal group discounted condom-protected sex more than participants in the partner-arousal group, but only when the arousal level was 50% and 100%. This could be because participants’ own (vs. partners’) arousal levels are a more salient driver of their decisions to use a condom. However, when the arousal to be achieved from condom use was very low (10%), sex with a condom might be undesirable (e.g., expected low quality of sex) for most participants regardless of whose arousal was affected.

Additionally, across partner conditions, men (vs. women) had higher rates of SADD (i.e., preference for sooner time to reach higher levels of sexual arousal without a condom), especially when condom use would delay and reduce their own (vs. partner’s) arousal.

Study 3

The findings from Studies 1 and 2 were both based on undergraduate students who participated for a course credit. Study 3 aimed to replicate those findings using a broader, more general sample. Thus, participants for Study 3 were recruited from a large online research platform that allowed people across the United States to volunteer in research studies. Compared to Studies 1 and 2, participants in Study 3 were older on average (Mage = 30 vs. ≤ 19 in the first two studies) and tended to be more sexually experienced (96% had had sexual intercourse vs. < 70% in the first two studies).

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited online via ResearchMatch.org and voluntarily participated in our online study (no compensation). Data were collected between March and September 2020. After data exclusion (see details in the Procedure section), the final sample was 227 participants (Mage = 30.48, SD = 5.57; range 19 to 42 years; 84% ≥ 25 years old; 67.8% female). The majority identified as heterosexual (70%), with the rest of the sample consisting of bisexual (20.7%), gay (men; 4.0%) and other sexual orientations not on the list (4.8%). Most of the sample (78%) were European White. The rest consisted of 8.4% Hispanic/Latino, 4.4% Asian, 2.6% Black, 3.5% Biracial/Multiracial, 0.4% Native American, and 1.8% other race not on the list. In terms of education, 41.9% had a degree higher than a bachelor’s degree, 32.2% had a bachelor’s degree, and the rest (25.5%) had not received (or were working toward receiving) a bachelor’s degree. Most participants (95.6%) reported having had experience in sexual intercourse.

Procedure, Measures, and Data Analysis

All procedures, measures, and analysis plans were the same as in Study 2. During the partner selection process, one participant (female) was excluded for selecting fewer than two partners and 29 participants were excluded for selecting the same picture for both partner categories.

As in Study 2, some participants reported zero willingness to use a condom at the baseline (no delay) of each trial3, meaning their data in that trial were undefined after standardization. Further, of the datasets that were flagged as potentially nonsystematic (2%), eight were removed because they had two or more points that met nonsystematic criteria. One participant had nonsystematic data in at least half of the trials, and thus was removed entirely from the analysis. For condom use self-efficacy, we again averaged all items to get a composite score (M = 3.42, SD = 0.55), with higher scores indicating higher self-efficacy (α = .87). Like Study 1, sexually experienced and inexperienced participants did not differ in terms of discounting rates, and thus were analyzed together as a whole.

Results

Figure 6 illustrates the discounting patterns from the three arousal trials (100%, 50%, and 10%) within the two partner conditions (most desirable and least STI).

Figure 6.

Raw reported willingness to use a condom (median) from Study 3. The left panel shows the ratings for the most desirable partner. The right panel shows the ratings for the least STI partner (perceived as least likely to have an STI).

Difference between partner conditions.

Similar to Study 2, within the 100% arousal trial, there was no statistically significant difference between AUCs for the most-desirable (Mdn = 0.92) and the least-STI partner conditions (Mdn = 0.88, p = .339). Unlike Study 2, the AUCs in the most-desirable and least-STI partner conditions were not different neither in the 50% trial (Mdns = 0.90 vs. 0.89, p = .217) nor the 10% trial (Mdns = 0.97 vs. 0.95, p = .466).

Difference between arousal targets.

Figure 7 shows the AUCs from the self-arousal and partner-arousal groups in each of the three arousal levels and two partner conditions. Results showed that, in the most-desirable partner condition, the self-arousal group (Mdn = 0.69) had lower AUC than the partner-arousal group (Mdn = 0.99) in the 100% arousal trial (U = 3,920, z = 3.12, p = .002). Similarly, the self-arousal group (Mdn = 0.73) had lower AUC than the partner-arousal group (Mdn = 0.98) in the 50% arousal trial (U = 3,987, z = 2.66, p = .008). Unlike Study 2, there was also a significant difference between the self-arousal group (Mdn = 0.89) and the partner-arousal group (Mdn = 1.00) in the 10% arousal trial (U = 3,520, z = 2.18, p = .029).

Figure 7.

Violin plots showing AUCs from the partner-arousal group and the self-arousal group (Study 3). The upper panel represents the most desirable partner, and the lower panel represents the least STI partner. The x-axis shows each of the three arousal levels (from left to right): 100%, 50%, and 10%. The width of each curve of the violin plot corresponds with the approximate frequency of data points in each region. Within each violin plot resides a box plot; the first quartile marks one end of the box and the third quartile marks the other end of the box. The horizontal line inside the box represents the median. The whisker line extends from the end of the box to the minimum value. Dots represent outlier (or extreme) values. AUC = area under the discounting curve (ranging from 0 to 1). Lower AUC = higher discounting.

In the least-STI partner condition, the self-arousal group (Mdn = 0.70) had lower AUC than the partner-arousal group (Mdn = 0.95) in the 100% arousal trial (U = 3,890, z = 3.47, p < .001). Similarly, the self-arousal group (Mdn = 0.75) had lower AUC than the partner-arousal group (Mdn = 0.98) in the 50% arousal trial (U = 3,641, z = 3.32, p < .001). Unlike Study 2, there was also a significant difference between the self-arousal group (Mdn = 0.82) and the partner-arousal group (Mdn = 1.00) in the 10% arousal trial (U = 3,156, z = 2.68, p = .007).

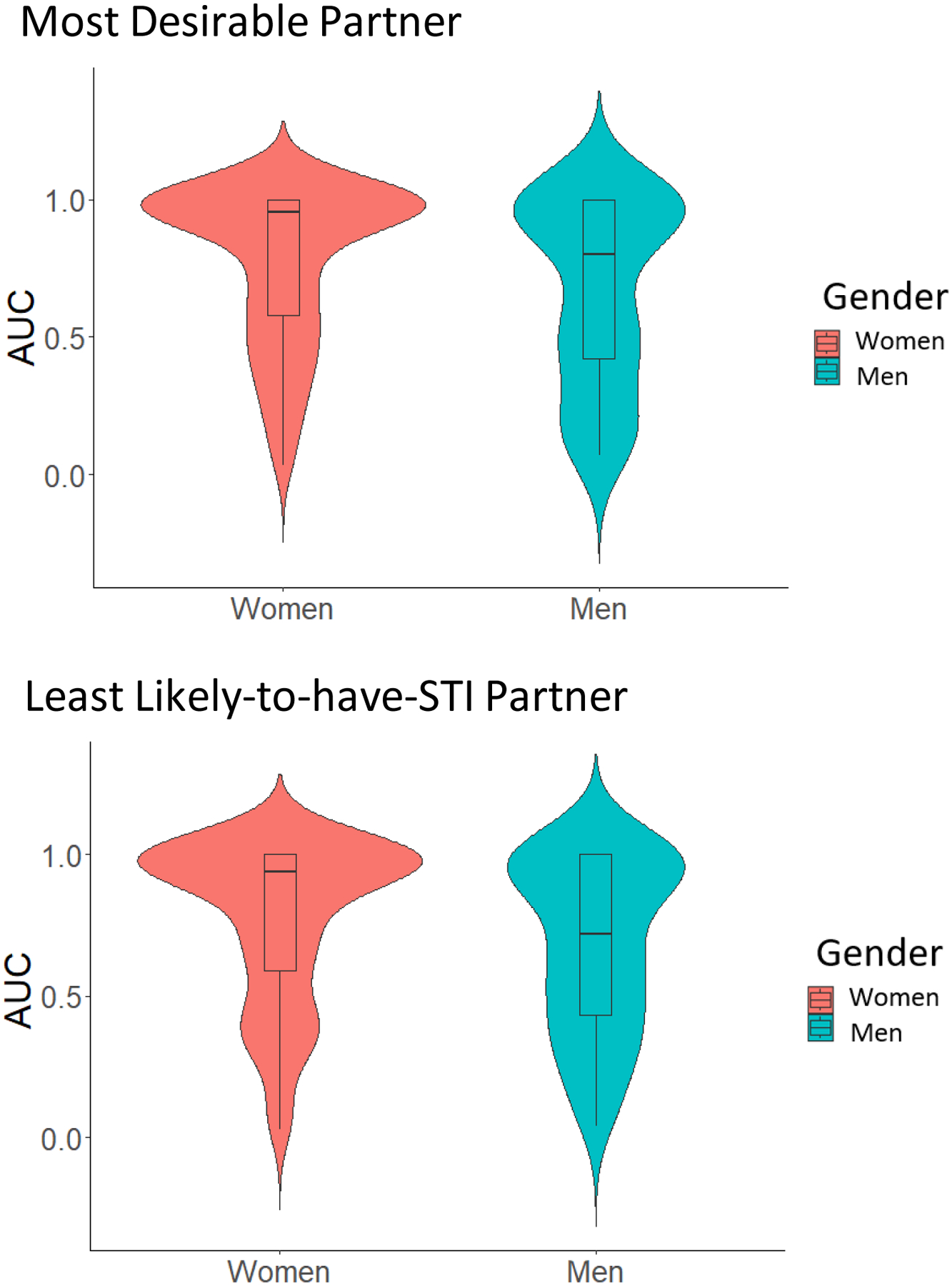

Difference between genders.

Men had lower AUC than women in both most-desirable-partner (Mdn = 0.80 vs. 0.96; U = 5,594, z = 2.19, p = .029) and least-STI-partner conditions (Mdn = 0.72 vs. 0.94; U = 5,658, z = 2.05, p = .040). Unlike Study 2, these differences were not significant when breaking the gender comparisons by arousal-target groups. Figure 8 illustrates men’s and women’s AUCs separated by partner conditions.

Figure 8.

AUCs separated by genders and partner conditions (Study 3). AUC = area under the discounting curve (ranging from 0 to 1). Lower AUC = higher discounting.

Relationship with condom use self-efficacy.

For the most-desirable partner condition, results from the Friedman test did not show a significant difference between the 100% and 50% arousal levels (p = .219). Thus, we averaged the AUCs from the two arousal levels (“higher arousal”). The AUC from the 10% arousal level (“lower arousal”) significantly differed from that of the 100% arousal (p = .049), and thus was retained for the analysis. Results showed that condom use self-efficacy was positively related to mean AUCs from both the higher arousal levels (r = .42, p < .001) and lower arousal level (r = .34, p < .01).

For the least-STI partner condition, we averaged the AUCs from the 100% and 50% arousal levels (“higher arousal”), due to the lack of a significant difference between the two (p = .279). The AUC from the 10% arousal level (“lower arousal”) significantly differed from that of the 100% arousal (p = .002), and thus was retained separately for the analysis. Results showed that the mean AUCs from both higher and lower arousal levels were positively related to condom use self-efficacy (rs = .39 and .35, ps < .001).

Discussion

The results replicated some of our previous findings. First, participants in the self-arousal group discounted delayed-arousal condom-protected sex more than those in the partner-arousal group across all arousal levels (in Study 2, the significant results emerged only in the 50% and 100% arousal levels). Second, men displayed higher discounting than women in both partner conditions. Third, higher discounting (regardless of arousal levels) was associated with lower condom use self-efficacy. Unlike Study 2, we did not find a significant difference in AUC between the most-desirable and least-STI partner conditions in any of the arousal trials.

General Discussion

Collectively, results across the three studies show support for the effects of sexual arousal and delay on individuals’ willingness to use a condom. Willingness to use a condom decreased as condom use increasingly delayed sexual arousal, and especially when the arousal was relatively low (e.g., 10%). This effect of delay to arousal was stronger when a condom affected participants’ own arousal (vs. their partner’s). We found mixed evidence for the effects of partner characteristics on SADD. In Study 2, people were more likely to discount condom-protected sex with delayed arousal when the partner was highly desirable compared to when the partner was perceived as having low STI risks. Such difference occurred only when the maximum arousal achieved after the delay was reduced by condom use (50% and 10%). This partner effect, however, was not replicated in Study 3. Additionally, results showing gender differences, such that men displayed higher discounting than women, are in line with the larger sexual discounting literature (Gebru et al., 2022; Johnson et al., 2021). Finally, we found evidence for the relationship between SADD and condom use self-efficacy across three studies. That is, greater discounting was associated with lower confidence in using a condom, supporting the SADD task’s ability to capture processes relevant to condom use behavior.

Effects of delayed arousal on willingness to use a condom

Discounting data from the SADD task were largely systematic, following previously established criteria (Johnson et al., 2015; Johnson & Bickel, 2008) for identifying nonsystematic discounting data. That is, as the delay to an outcome (i.e., achieving a certain amount of arousal) increased due to condom use, people’s willingness to use a condom decreased.

Wongsomboon and Cox’s (2021) study shows that reduced arousal resulting from condom use can reduce people’s reported willingness to use condom. Results of the current investigation extend these findings, showing that individuals’ willingness to use a condom also decreases systematically as a function of the delay until sexual arousal is achieved. In addition to the role of time (i.e., delay) to achieving arousal, the level of arousal to be achieved (low or high) also impacts willingness to use a condom. That is, when a condom necessitated some time for sexual arousal to reach its peak, participants were more willing to use a condom if they could still achieve high levels of arousal (e.g., 100%) compared to if the maximum arousal to be achieved would be low (e.g., 10%) even after the delay.

Past research shows that individuals report reduced willingness to use condoms because of several reasons, including reduced arousal, pleasure, and sexual sensation (Graham et al., 2011; Sanders et al., 2012). Research suggests that individuals who have experienced condom related problems (e.g., breakage) need more time and/or more intense sexual stimulation to achieve arousal (Janssen et al., 2014). The current study examined one avenue by which condom use willingness was associated with perceptions of condom-related arousal. Specifically, the findings indicate that condom use willingness may also be reduced by the increasing amount of time it takes to achieve arousal (i.e., sexual arousal-delay discounting). Future research should examine relationships between SADD and condom-related outcomes (e.g., reported pleasure) to determine the extent to which past experiences with condom use and perceptions are related to SADD.

In Studies 2 and 3, when there was no delay associated with sexual arousal (i.e., the no-delay condition), we observed considerably higher condom use willingness when the condom did not affect arousal (the 100% arousal) than when it did (the 50% and 10% arousal). Future research should further validate the SADD task to help tailor interventions for condom use promotion. For example, while sex educational efforts to debunk condom-related myths may be appropriate for individuals who are generally unwilling to use a condom (Anderson et al., 2017; Helmer et al., 2015), different intervention methods (e.g., set a condom carrying reminder, recommend condoms designed for increased pleasure) may be needed for those who are interested in using a condom initially but could be influenced by situational or contextual barriers.

Effects of arousal target on willingness to use a condom

Participants’ willingness to use a condom varied based on whose arousal was reduced by condom use (i.e., arousal target). Overall findings suggest that the impacts of condom-associated sexual problems (e.g., reduced arousal) on condom use decisions may depend on whether a condom affects their own or their partners’ sexual function. Findings are in line with research that suggests individuals’ sexual pleasure during condom use is related to their own and their partners’ comfort levels during sex (Hensel et al., 2012). However, whether the findings can generalize to different arousal levels needs further investigation.

Current findings showing that willingness to use a condom decreases as delay to one’s own arousal increases are in line with past research. Evidence, particularly with men who have sex with men, has suggested that pleasure is one of the most common reasons for condom non-use (Carballo-Diéguez et al., 2006; Higgins & Wang, 2015; Randolph et al., 2007; Sarno et al., 2021). Therefore, in addition to emphasizing a disease prevention model (e.g., using condoms to avoid HIV infections), recent education and intervention efforts have now started to emphasize pleasure-enhancing aspects of condom use (e.g., eroticization of condom use/safe sex; Zaneva et al., 2022). Indeed, meta-analytic evidence shows that incorporating pleasure in interventions improves sexual health outcomes (Zaneva et al., 2022). Current findings suggest that such efforts may need to emphasize people (particularly men)’s own sexual functioning and pleasure in promoting condom use (e.g., how to use a condom to enhance your sexual pleasure) in addition to partner-focused messages (e.g., using a condom to sexually please your partner).

Although reduction in one’s own arousal had more impact on participants’ SADD, reductions in a partner’s sexual arousal also seemed to influence their willingness to use a condom at least to some extent. This suggests that condom use may also be seen as a barrier to the partner’s sexual pleasure. Fear of stigma and rejection when negotiating condom use with a partner is associated with reduction in condom use willingness (Sarno et al., 2021). Findings from the current study highlight partner-specific factors that can affect individuals’ condom use decisions. HIV/STI prevention efforts aimed at increasing condom use may benefit from targeting those who are more likely than others to be influenced by their partners’ attitudes toward condom use. Future education and intervention programs should address nuances of condom use negotiation and communication with sexual partners to increase overall condom use related skills.

Effects of partner characteristics on willingness to use a condom

In both Studies 2 and 3, partner comparisons revealed that participants’ willingness to use a condom with their most desirable (vs. least STI-risk) partners did not significantly differ when they (or their partner) could achieve full (100%) arousal. At the half (50%) and low (10%) arousal levels, participants in Study 2 discounted delayed-arousal condom-protected sex more with their most desirable (vs. least STI-risk) partners. This finding, however, was not replicated in Study 3. This lack of differences between the two partners is not entirely surprising. Past research on sexual delay discounting shows that highly desirable partners and partners perceived as “disease free” tend to elicit relatively high discounting rates (Johnson & Bruner, 2012). Future work may compare discounting rates, as has been done in much of the sexual discounting research, between partners who differ on the same dimension (e.g., most vs. least desirable; most vs least likely to have STI) to further assess the effect of partner characteristics on SADD.

Limitations and Future Directions

Findings should be interpreted in the context of study limitations. First, although we tried to replicate the findings across different samples, they still consisted of relatively highly educated and mostly heterosexual people (recruited via convenience sampling). Future research should examine SADD in populations with different socio-economic and demographic backgrounds as well as those more vulnerable for HIV/STI acquisition (e.g., men who have sex with men). Future research may also examine SADD in women who have sex with women using different protection methods other than condoms (e.g., dental dams).

Findings regarding differences in discounting by partner types (i.e., most desirable vs. least STI risk) were found in Study 2 but were not fully replicated in Study 3. This could be due to various reasons, such as potential differences between college versus non-college samples and/or age differences (Skaletz-Rorowski et al., 2020), as well as potential differences in risk perceptions and “optimism bias” that is more pronounced in younger individuals (Lopez & Leffingwell, 2020) – all of which can be examined in future studies.

Second, participants in this study were not given an “opt-out” option as in Wongsomboon and Cox (2021). In that study, participants were able to opt-out of having sex altogether at any point in time (instead of choosing between condom-protected sex and condomless sex). The current study did not include such an option because it was the first to combine the arousal and delay discounting tasks. We considered it important to examine discounting patterns from everyone including those who may want to end sexual encounters after some arousal or delay. However, this could create ecological validity problems. For example, given the relatively high willingness to use condoms, especially in Study 3, it remains unknown whether participants who reported high willingness to use a condom did so because they truly wanted to have condom-protected sex (even at the lowest arousal and after the longest delay) or because the no-sex option was not available to them. To maximize real-world implications, future studies should replicate the SADD task with an opt-out option.

Third, using the same method as past discounting studies (Johnson & Bruner, 2012; Wongsomboon & Cox, 2021), participants responded to delay durations and arousal levels that increased or decreased in fixed order (i.e., no counterbalancing or randomization). As such, we cannot rule out the possibility of a response bias (Robles et al., 2009). Future studies with the SADD task could also vary the order of presentation of delay lengths and arousal levels to enhance confidence in observed effects.

Next, given evidence that attractive persons tend to be perceived as having low STI risk (Eleftheriou et al., 2016), it is possible that participants in our study perceived the most desirable partner as somewhat low in STI risk. Although we had excluded those who selected the same picture for both partners to allow for cross-category comparisons, we cannot rule out the possibility that the two partner categories (most desirable and least STI risk) were more or less the same.

Further, although condoms are one of the most effective HIV/STI prevention methods (CDC, 2020), the current study did not assess the impact of other HIV prevention tools (e.g., pre-exposure prophylaxis; PrEP) on the SADD task. Condom use decisions are likely affected by the use of other HIIV-risk-reduction tools such as PrEP (Sarno et al., 2021). Future studies could examine the role of SADD and overall willingness to use condoms in the context of PrEP.

In addition, using a hypothetical scenario, the current SADD task did not examine the real emotional state of real sexual arousal. Robust literature has provided support for the use of hypothetical tasks to measure various behavioral constructs of interest, including likelihood of condom use as a function of delay (Johnson et al., 2021). However, future studies may include a manipulation of actual arousal (e.g., using priming methods) in the SADD task to test if the findings replicate, and enhance, the ecological validity of the task. Further, the definition of “sexual arousal” in our SADD task focused mainly on physiological responses, and thus did not encompass other subjective dimensions. The hypothetical scenario used in the SADD task may have also been interpreted differently between men and women; thus, gender differences should be more systematically examined in the future. Taken together, although the SADD task allows for systematic study of sexual health decision-making as a function of delay to arousal, it may have limited ecological validity. Future studies should find ways to manipulate the variables of interest (e.g., delay, arousal) while making the task as realistic as possible. Future research should also assess the predictive utility of the task by examining relations between SADD task and self-reported sexual behaviors.

It is also important to note that the relationship between SADD and condom use self-efficacy was correlational in nature. Future research should aim to establish a causal inference using appropriate designs (e.g., experimental, longitudinal). Future studies may also examine the associations between SADD and other indicators of sexual health (e.g., reported frequency of condom use, STI occurrence) to further assess the validity and real-world utility of the SADD task.

Conclusion

The SADD task provides a unique and quantifiable way to measure condom use decision-making and behavior. Across three studies, we found a systematic reduction in people’s willingness to use condoms as condoms reduced and delayed sexual arousal. Taken together, the current study shows various ways in which condom use decisions can be influenced by arousal and delay to arousal, as well as the interactions with partner characteristics and arousal target. This study demonstrates how the discounting framework can be applied to research on sexuality and sexual behavior. The findings have important implications for sex education and intervention efforts to promote condom use and reduce STI transmissions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement:

We thank Dr. David J. Cox for his advice and suggestions throughout the project. We thank Dr. Gregory D. Webster for his mentorship and supervision.

Footnotes

In some cases, (from less than 1% to 6% of the sample in the three studies), the willingness to use a condom rating (raw value) in the no-delay item was not the highest value, which resulted in AUC higher than 1.0. To keep AUC at or below 1.0, in most cases, we divided all raw values by the highest value within the same trial (Wongsomboon & Cox, 2021). We capped the AUC to 1.0 if (a) all raw values were single digit numbers (i.e., less than 10), (b) the highest value was in the longest or second longest delay item, and (c) all values were the same or almost the same (difference ≤ 5) across delay items (Gebru et al., 2022; Johnson et al., 2021).

For the most desirable partner, at no delay, zero willingness to use a condom was reported by 7 participants in the 100% arousal, 6 participants in the 50% arousal, and 16 participants in the 10% arousal condition. For the partner least likely to have an STI, at no delay, zero willingness to use a condom was reported by 3 participants in the 100% arousal, 4 participants in the 50% arousal, and 17 participants in the 10% arousal condition.

For the most-desirable partner condition, n = 7 in the 100% arousal, n = 7 in the 50% arousal, and n = 25 in the 10% arousal trials reported zero willingness to use condoms at baseline. For the least-STI partner condition, n = 1 in the 100% arousal, n = 11 in the 50% arousal, and n = 30 in the 10% arousal trials reported zero willingness to use condoms at baseline.

References

- Amlung M, Marsden E, Holshausen K, Morris V, Patel H, Vedelago L, Naish KR, Reed DD, & McCabe RE (2019). Delay discounting as a transdiagnostic process in psychiatric disorders: A meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry, 76(11), 1176–1186. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.2102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson MB, Okwumabua TM, & Thurston IB (2017). Condom carnival: Feasibility of a novel group intervention for decreasing sexual risk. Sex Education, 17(2), 135–148. 10.1080/14681811.2016.1252741 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Freitas-Lemos R, Tomlinson DC, Craft WH, Keith DR, Athamneh LN, Basso JC, & Epstein LH (2021). Temporal discounting as a candidate behavioral marker of obesity. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 129, 307–329. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.07.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Johnson MW, Koffarnus MN, MacKillop J, & Murphy JG (2014). The behavioral economics of substance use disorders: Reinforcement pathologies and their repair. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 10(1), 641–677. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032813-153724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carballo-Diéguez A, Miner M, Dolezal C, Rosser BRS, & Jacoby S (2006). Sexual negotiation, HIV-status disclosure, and sexual risk behavior among Latino men who use the internet to seek sex with other men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 35(4), 473–481. 10.1007/s10508-006-9078-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. (2021). Adolescents and young adults | Prevention | STDs | CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/std/life-stages-populations/adolescents-youngadults.htm

- CDC. (2022, April 7). HIV by age: HIV incidence. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/age/incidence.html [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2020). HIV basics | HIV/AIDS | CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/basics/index.html

- Crosby R, Milhausen R, Yarber WL, Sanders SA, & Graham CA (2008). Condom ‘turn offs’ among adults: An exploratory study. International Journal of STD & AIDS, 19(9), 590–594. 10.1258/ijsa.2008.008120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fennell J (2014). “And Isn’t that the point?”: Pleasure and contraceptive decisions. Contraception, 89(4), 264–270. 10.1016/j.contraception.2013.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebru NM, Kalkat M, Strickland JC, Ansell M, Leeman RF, & Berry MS (2022). Measuring sexual risk-taking: A systematic review of the sexual delay discounting task. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 51(6), 2899–2920. 10.1007/s10508-022-02355-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham CA, Crosby RA, Milhausen RR, Sanders SA, & Yarber WL (2011). Incomplete use of condoms: The importance of sexual arousal. AIDS and Behavior, 15(7), 1328–1331. 10.1007/s10461-009-9638-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham CA, Crosby R, Yarber WL, Sanders SA, McBride K, Milhausen RR, & Arno JN (2006). Erection loss in association with condom use among young men attending a public STI clinic: Potential correlates and implications for risk behaviour. Sexual Health, 3(4), 255–260. 10.1071/sh06026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green L, & Myerson J (2004). A discounting framework for choice with delayed and probabilistic rewards. Psychological Bulletin, 130(5), 769–792. 10.1037/0033-2909.130.5.769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmer J, Senior K, Davison B, & Vodic A (2015). Improving sexual health for young people: Making sexuality education a priority. Sex Education, 15(2), 158–171. 10.1080/14681811.2014.989201 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hensel DJ, Stupiansky NW, Herbenick D, Dodge B, & Reece M (2012). Sexual pleasure during condom-protected vaginal sex among heterosexual men. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 9(5), 1272–1276. 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02700.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann ES, Johnson PS, & Johnson MW (2015). Examining delay discounting of condom-protected sex among men who have sex with men using crowdsourcing technology. AIDS and Behavior, 19(9), 1655–1665. 10.1007/s10461-015-1107-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JA, & Wang Y (2015). The role of young adults’ pleasure attitudes in shaping condom use. American Journal of Public Health, 105(7), 1329–1332. 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen E, Sanders SA, Hill BJ, Amick E, Oversen D, Kvam P, & Ingelhart K (2014). Patterns of sexual arousal in young, heterosexual men who experience condom-associated erection problems (CAEP). The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 11(9), 2285–2291. 10.1111/jsm.12548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MW, & Bickel WK (2008). An algorithm for identifying nonsystematic delay-discounting data. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 16(3), 264–274. 10.1037/1064-1297.16.3.264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MW, & Bruner NR (2012). The sexual discounting task: HIV risk behavior and the discounting of delayed sexual rewards in cocaine dependence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 123(1–3), 15–21. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.09.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MW, Johnson PS, Herrmann ES, & Sweeney MM (2015). Delay and probability discounting of sexual and monetary outcomes in individuals with cocaine use disorders and matched controls. PLoS ONE, 10(5). 10.1371/journal.pone.0128641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MW, Strickland JC, Herrmann ES, Dolan SB, Cox DJ, & Berry MS (2021). Sexual discounting: A systematic review of discounting processes and sexual behavior. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 29(6), 711–738. 10.1037/pha0000402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez SV, & Leffingwell TR (2020). The role of unrealistic optimism in college student risky sexual behavior. American Journal of Sexuality Education, 15(2), 201–217. 10.1080/15546128.2020.1734131 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mausbach BT, Semple SJ, Strathdee SA, Zians J, & Patterson TL (2007). Efficacy of a behavioral intervention for increasing safer sex behaviors in HIV-positive MSM methamphetamine users: Results from the EDGE study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 87(2), 249–257. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.08.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myerson J, Green L, & Warusawitharana M (2001). Area under the curve as a measure of discounting. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 76(2), 235–243. 10.1901/jeab.2001.76-235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randolph ME, Pinkerton SD, Bogart LM, Cecil H, & Abramson PR (2007). Sexual pleasure and condom use. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 36(6), 844–848. 10.1007/S10508-007-9213-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen EB, Lawyer SR, & Reilly W (2010). Percent body fat is related to delay and probability discounting for food in humans. Behavioural Processes, 83(1), 23–30. 10.1016/j.beproc.2009.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robles E, Vargas PA, & Bejarano R (2009). Within-subject differences in degree of delay discounting as a function of order of presentation of hypothetical cash rewards. Behavioural Processes, 81(2), 260–263. 10.1016/j.beproc.2009.02.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders SA, Hill BJ, Janssen E, Graham CA, Crosby RA, Milhausen RR, & Yarber WL (2015). General erectile functioning among young, heterosexual men who do and do not report condom‐associated erection problems (CAEP). The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 12(9), 1897–1904. 10.1111/jsm.12964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders SA, Yarber WL, Kaufman EL, Crosby RA, Graham CA, & Milhausen RR (2012). Condom use errors and problems: A global view. Sexual Health, 9(1), 81–95. 10.1071/SH11095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarno EL, Macapagal K, & Newcomb ME (2021). “The main concern is HIV, everything else is fixable”: Indifference toward sexually transmitted infections in the era of biomedical HIV prevention. AIDS and Behavior, 25(8), 2657–2660. 10.1007/s10461-021-03226-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skaletz-Rorowski A, Potthoff A, Nambiar S, Wach J, Kayser A, Kasper A, & Brockmeyer NH (2020). Age specific evaluation of sexual behavior, STI knowledge and infection among asymptomatic adolescents and young adults. Journal of Infection and Public Health, 13(8), 1112–1117. 10.1016/j.jiph.2020.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strickland JC, Lee DC, Vandrey R, & Johnson MW (2021). A systematic review and meta-analysis of delay discounting and cannabis use. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 29, 696–710. 10.1037/pha0000378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wongsomboon V, & Cox DJ (2021). Sexual arousal discounting: Devaluing condom-protected sex as a function of reduced arousal. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 50(6), 2717–2728. 10.1007/s10508-020-01907-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wongsomboon V, & Robles E (2017). Devaluation of safe sex by delay or uncertainty: A within-subjects study of mechanisms underlying sexual risk behavior. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46(7), 2131–2144. 10.1007/s10508-016-0788-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wongsomboon V, & Shepperd JA (2022). Waiting for medical test results: A delay discounting approach. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 311, 115355. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.115355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wongsomboon V, & Webster GD (2023). Delay discounting for HIV/STI testing. Sexuality Research and Social Policy. 10.1007/s13178-023-00819-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaneva M, Philpott A, Singh A, Larsson G, & Gonsalves L (2022). What is the added value of incorporating pleasure in sexual health interventions? A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS ONE, 17(2), e0261034. 10.1371/journal.pone.0261034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.