Abstract

Background:

Postpartum hemorrhage remains a leading cause of maternal mortality especially in developing countries. The majority of previous trials on the effectiveness of tranexamic acid in reducing blood loss were performed in low-risk women for postpartum hemorrhage. A recent Cochrane Systematic Review recommended that further research was needed to determine the effects of prophylactic tranexamic acid for preventing intraoperative blood loss in women at high risk of postpartum hemorrhage.

Objective:

This study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of tranexamic acid in reducing intraoperative blood loss when given prior to cesarean delivery in women at high risk of postpartum hemorrhage.

Study design:

The study is a double-blind randomized controlled trial.

Methods:

The study consisted of 200 term pregnant women and high-risk preterm pregnancies scheduled for lower-segment cesarean delivery at Enugu State University of Science and Technology, Teaching Hospital, Parklane, Enugu, Nigeria. The participants were randomized into two arms (intravenous 1 g of tranexamic acid or placebo) in a ratio of 1:1. The participants received either 1 g of tranexamic acid or placebo (20 mL of normal saline) intravenously at least 10 min prior to commencement of the surgery. The primary outcome measures were the mean intraoperative blood loss and hematocrit change 48 h postoperatively.

Results:

The baseline sociodemographic characteristics were similar in both groups. The tranexamic acid group when compared to the placebo group showed significantly lower mean blood loss (442.94 ± 200.97 versus 801.28 ± 258.68 mL; p = 0.001), higher mean postoperative hemoglobin (10.39 + 0.96 versus 9.67 ± 0.86 g/dL; p = 0.001), lower incidence of postpartum hemorrhage (1.0% versus 19.0%; p = 0.001), and lower need for use of additional uterotonic agents after routine management of the third stage of labor (39.0% versus 68.0%; p = 0.001), respectively. However, there was no significant difference in the mean preoperative hemoglobin (11.24 ± 0.88 versus 11.15 ± 0.90 g/dL; p = 0.457), need for other surgical intervention for postpartum hemorrhage (p > 0.05), and reported side effect, respectively, between the two groups.

Conclusion:

Prophylactic administration of tranexamic acid significantly decreases postpartum blood loss, improves postpartum hemoglobin, decreases the need for additional uterotonics, and prevents postpartum hemorrhage following cesarean section in pregnant women at high risk of postpartum hemorrhage. Its routine use during cesarean section in high-risk women may be encouraged.

The trial was registered in the Pan-African Clinical Trial Registry with approval number PACTR202107872851363.

Keywords: blood loss, cesarean section, high risk, postpartum hemorrhage, prophylaxis, tranexamic acid

Introduction

Postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) is the single most significant leading cause of pregnancy-related mortality, accounting for about 27% of maternal deaths globally and up to 60% in some developing nations. 1 The most frequent major procedure carried out globally is cesarean delivery. Intraoperative and postoperative maternal hemorrhage is the most common postoperative complication in high-risk cesarean delivery women. 2

The administration of tranexamic acid, a fibrinolysis inhibitor, was linked to a significant decline in overall mortality among patients with PPH. 3 Tranexamic acid is a synthetic derivative of the amino acid Lysine that reversibly inhibited the activation of plasminogen. Its action inhibited fibrinolysis and reduced blood loss. 4

It is noteworthy that there were previously published studies on tranexamic acid but the study populations were largely on women who were not at high risk of PPH. 5 Franchini et al. reported 18 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that involved the use of intravenous tranexamic acid and placebo. The overall result of the meta-analysis was in support of tranexamic acid in reducing blood loss and decreasing the need for blood transfusion during cesarean section (CS). However, these previous RCTs were not done on pregnant women at high risk of PPH. 5 A recent Cochrane review by Novikova and co-workers concluded that tranexamic acid is an effective drug for reducing intraoperative blood loss based on data from trials in low-risk women. The authors of Novikova et al.’s study also concluded that further research was needed to examine the effects of tranexamic acid for reducing intraoperative blood loss in high-risk women at high risk of PPH. Therefore, there was lack of evidence from RCTs to comparably appraise the benefits and risks of tranexamic acid and placebo when given to reduce intraoperative blood loss during CS in pregnant women at high risk of PPH. 6

The only prior randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study that evaluated the effect of tranexamic acid in a Nigerian pregnant population was the World Maternal Antifibrinolytic (WOMAN) trial. 7 The WOMAN trial was an international, randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled trial of women with a clinical diagnosis of PPH after a vaginal birth or CS. Therefore, in the WOMAN trial, tranexamic acid was administered as treatment intent rather than a prophylactic intent. The drugs used in the WOMAN trial were also administered at a postpartum period rather than in the antepartum or intrapartum period. A study comparing the efficacy and adverse effects of tranexamic acid and placebo for reducing intraoperative blood loss during CS in pregnant women at high risk of PPH was therefore desirable.

Therefore, this study aimed to compare the efficacy and adverse effects of prophylactic tranexamic acid and placebo for reducing intraoperative blood loss during CS in women at high risk of PPH.

Methods

Study design

This is a double-blind RCT.

Study setting

The study was conducted at Enugu State University of Science and Technology (ESUT), Teaching Hospital, Parklane, Enugu, South East, Nigeria, from 19 July 2021 to 28 February 2022. The approval for the study protocol was obtained from the ethics review committee of ESUT Teaching Hospital, Parklane, Enugu, Nigeria.

Study population

The study was conducted among consenting high-risk pregnant women at term who were delivered by lower-segment CS.

Inclusion criteria

Those included in the study were term high-risk pregnant women with a previous history of PPH, co-existing uterine fibroid, multiple pregnancy, previous CS, fetal macrosomia, placenta previa, multiple gestation, severe preeclampsia, eclampsia, and polyhydramnios.

Exclusion criteria

Those excluded from the study were participants who had uterine rupture, intrauterine fetal death, history of bleeding disorders, history of thromboembolism, significant antepartum hemorrhage, and known allergy to tranexamic acid and unbooked patients with prolonged obstructed labor.

Sample size determination

The sample size, n = (U + V)2 (SD12 + SD22)/(U1 − U2)2, was determined using the power analysis formula.8,9 Based on the power of 90% and estimated attrition rate of 10%, the minimum sample size required for this study was 100 participants in each study arm.

Randomization/sampling technique

Recruited participants were randomly allotted into two equal arms (1:1), namely, the preoperative intravenous tranexamic acid and placebo arms using a computer-generated random number. Randomization was performed by an independent person who was not involved in the study using randomly permuted blocks (blocks of four, allocation ratio of 1:1) with software available online (http://www.randomization.com). Eligible unbooked pregnant women presenting in the labor ward for the first time were recruited after written informed consent was given.

Study procedure

Having obtained a history, examined and reviewed the previous notes in the case file. An intravenous access was secured using a size-16G cannula and blood samples were collected from each patient prior to the CS and 48 h after the operation into an ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) bottle and sent to the hematological analysis to obtain the hematocrit levels using the microhematocrit centrifuge and reader (Haematokrit 210; Hettich, Germany). Bedside urinalysis was done to rule out proteinuria and glycosuria. The weight of the participant was obtained.

The stored pack containing either tranexamic acid (Prexam®; PROTECH Biosystems Pvt Ltd.,145, 146, Pace City I, Sector 37, Gurgaon, Haryana, India) or the placebo (normal saline, Juhel Nigeria Ltd, Nigeria) that were indistinguishable was prepared by a Pharmacist who was not a part of the study. This drug or placebo was opened by independent staff (nurse midwife on duty in labor ward) of the hospital. Following the opening of the pack containing the sequentially numbered syringe, the nurse on duty in the labor ward (who was also not part of the study) collected one of the numbered syringes containing either of the study or placebo agent and handed it over to the anesthetist. The anesthetist then administered the study drug (1 g of tranexamic acid solution (10 mL) made up to 20 mL with 10 mL of normal saline) or placebo (20 mL of normal saline) intravenously to the patients about 10 min prior to the onset of surgery. The placebo was used to blind the patient and the outcome assessor (researcher) and trained research assistants (research team) on the type of intervention agent used. The choice of anesthesia was determined by the surgeon and anesthetist after counseling the patient.

The cesarean delivery was carried out mostly under spinal anesthesia for the participants by the obstetric caregiver. A Pfannenstiel incision was used to gain access into the peritoneal cavity, and a transverse curvilinear lower-segment incision was made to deliver the baby. Following the delivery of the baby, 10 IU of intravenous oxytocin was administered within 1 min of the delivery of the baby, and the placenta was delivered by controlled cord traction. The uterus was exteriorized and repaired in two layers using standard technique. Hypotension and tachycardia were checked every 30 min during the surgery. All women received routine active management of the third stage of labor. Palpation of the tone of the uterus and uterine massage was done by the surgeon to assess for and prevent uterine atony. If there was significant intraoperative bleeding within 10 min of oxytocin injection adjudged to be only due to uterine atony, the uterus was further massaged, and additional uterotonics were administered at the discretion of the surgeon or anesthetist on duty. The additional uterotonics commonly used were 40 IU oxytocin in 1000 mL saline solution at 40 drops/min or intramuscular methylergometrine maleate, 0.5 mg, or 600 µg of rectal misoprostol. The patients were monitored for further intraoperative bleeding. The abdominal layers were closed with appropriate sutures. The vital signs were recorded every 15 min in the first hour and every 30 min in the second hour after delivery. The estimated blood loss (in mL) and history of side effects, such as shivering, pyrexia, and nausea/vomiting during the intraoperative period, were recorded.

Blood sample was drawn from the parturient for hematocrit measurement at 48 h postoperatively. In this study, primary atonic PPH was defined as blood loss of 1000 mL or more only due to uterine atony within the first 24 h after the delivery of the baby. The total estimated blood loss was calculated using the difference in hematocrit values taken prior to and 48 h after cesarean delivery, using GROSS EQUATION 10 : Estimated Blood Loss (EBL) = EBV × ((HCT1 − HCT2)/(HCT mean)), where EBL = Estimated Blood Loss, EBV = Estimated Blood volume; whereas EBV = Patient’s weight (in kilogram) × 70 mL/kg, HCT1 = preoperative hematocrit of study group or placebo group, HCT2 = postoperative hematocrit of study group or placebo group, and HCT mean = (HCT1 + HCT2)/2

Outcome measures

The primary outcome measures were the mean intraoperative blood loss during cesarean delivery and hematocrit change 48 h postoperatively. Secondary outcome measures were those who needed additional uterotonics and those who received blood transfusion intraoperatively, and if there was need for other surgical intervention for PPH (such as B-Lynch procedure or hysterectomy), the incidence of postpartum maternal anemia, and occurrence of adverse effects (nausea, vomiting, thromboembolism, coagulopathy, etc.) during the study period.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed with Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) software version 23 (SPSS Inc. Chicago, IL). Categorical data were compared using chi-square test, relative risk (RR), and 95% confidence interval (CI). For continuous data, the means were compared using Student’s t-test (unpaired and paired) or unpaired t-test, and presented in mean and standard deviation, mean difference, and 95% CI. Relationships were expressed using RRs and CIs. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

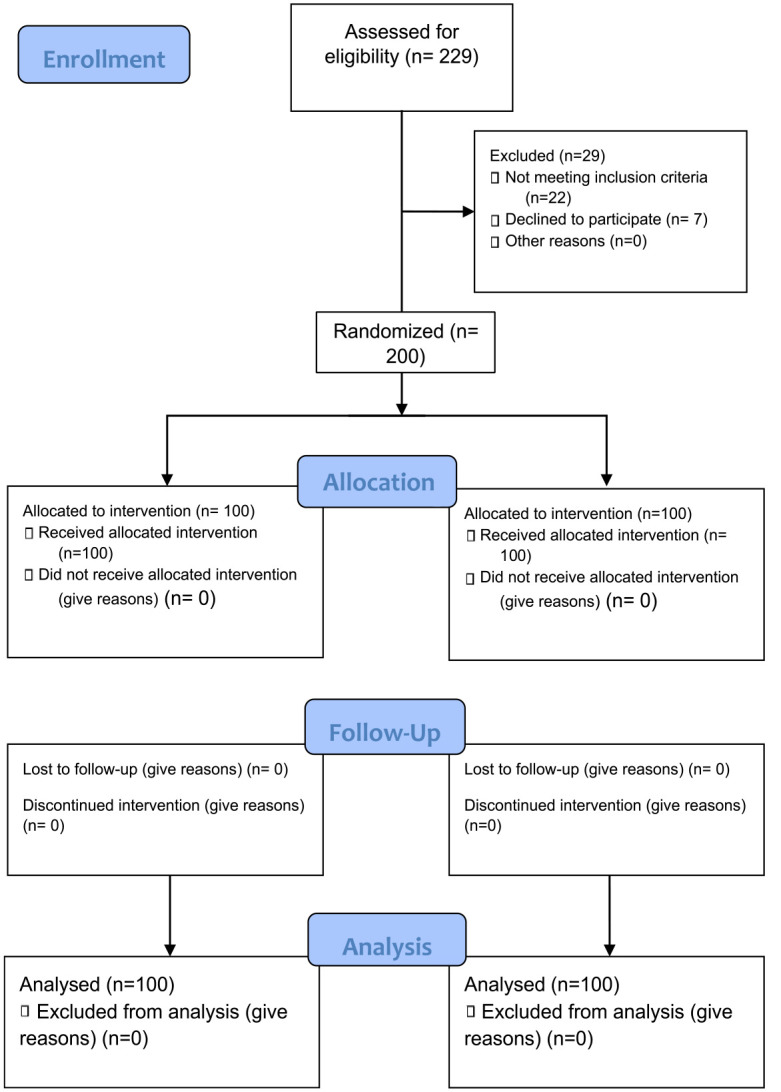

Within the study period, a total of 229 women were assessed for eligibility for the study. Of the 229 women who were assessed for eligibility for the study, 200 participants who met the inclusion criteria were randomized into the tranexamic acid group (n = 100) and placebo group (n = 100).

A flow diagram describing the participants’ flow through the study is shown in Figure 1. Table 1 summarized the sociodemographic characteristics of both groups. There was no significant difference in the baseline sociodemographic data of the two groups. The summary of the clinical indications for the CS was shown in Table 2. There was no significant difference in the indications for the CS between the two groups. There was equal distribution among the two groups and so no significant difference was obtained.

Figure 1.

Consort flowchart.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the participants.

| Variable | Tranexamic | Placebo | Total | χ2 (value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||

| Age group (years) | ||||

| 21–25 | 9 (9.0) | 8 (8) | 17 (8.5) | 2.29 (0.09) |

| 26–30 | 32 (32.0) | 31 (31) | 63 (31.5) | |

| 31–35 | 39 (39.0) | 36 (36) | 75 (37.5) | |

| 36–40 | 20 (20.0) | 22 (22) | 42 (21) | |

| 41–45 | 0 (0) | 3 (3) | 3 (1.5) | |

| M ± SD | 31.80 ± 4.40 | 32.04 ± 4.75 | 31.92 ± 4.57 | |

| Gestational age (weeks) | ||||

| 32–37 | 29 (29) | 32 (32) | 61 (30.5) | 0.09 (0.76) |

| ⩾38 | 71 (71) | 68 (68) | 139 (69.5) | |

| Booking status | ||||

| Booked | 67 (67) | 63 (63) | 130 (65) | 0.20 (0.67) |

| Unbooked | 33 (33) | 37 (37) | 70 (35) | |

| Gravity | ||||

| 0–4 | 89 (89) | 85 (85) | 174 (87) | 0.40 (0.53) |

| >5 | 11 (11) | 15 (15) | 26 (13.5) | |

| Parity | ||||

| 0–4 | 98 (98) | 100 (100) | 198 (99) | 0.51 (0.48) |

| >5 | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 2 (1) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||||

| Normal | 4 (4) | 6 (6) | 10 (5) | 1.47 (0.47) |

| Overweight | 49 (49) | 41 (41) | 90 (45) | |

| Obese | 53 (53) | 47 (47) | 100 (50) | |

| M ± SD | 29.08 ± 5.03 | 30.26 ± 3.81 | 29.67 ± 4.49 | |

| Duration of surgery (min) | ||||

| Less than 1 h | 58 (58) | 56 (56) | 114 (57) | 0.08 (0.77) |

| At least 1 h | 42 (42) | 44 (44) | 86 (43) | |

| M ± SD | 56.66 ± 15.67 | 59.95 ± 17.14 | 58.31 ± 16.46 | |

BMI: body mass index; SD: standard deviation.

Table 2.

Indications for the CS between the two groups.

| Indications | Tranexamic | Placebo | Total | χ2 (p-value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||

| Lower-segment fibroids | 5 (5.0) | 4 (4.0) | 9 (4.5) | 0.11 (0.74) |

| Placenta previa | 21 (21.0) | 25 (25.0) | 46 (31.5) | 0.35 (0.56) |

| One previous CS | 13 (13.0) | 15 (15.0) | 28 (37.5) | 0.14 (0.71) |

| Two previous CS | 15 (15.0) | 14 (14.0) | 29 (21.0) | 0.04 (0.85) |

| Preeclampsia | 5 (5.0) | 6 (6.0) | 11 (1.5) | 0.09 (0.76) |

| Eclampsia | 5 (5.0) | 6 (6.0) | 11 (5.5) | 0.09 (0.76) |

| Fetal macrosomia | 12 (12.0) | 11 (11.0) | 23 (11.5) | 0.04 (0.84) |

| Polyhydramnios | 4 (4.0) | 2 (2.0) | 6 (3.0) | 0.67 (0.41) |

| Twin gestation with T1 breech | 3 (3.0) | 4 (4.0) | 7 (3.5) | 0.14 (0.71) |

| High-order pregnancy | 4 (4) | 4 (4.0) | 8 (4.0) | 0.001 (0.99) |

| PPROM | 2 (33) | 1 (1.0) | 3 (1.5) | 0.33 (0.56) |

| Compound presentation | 2 (2) | 1 (1.0) | 3 (1.5) | 0.33 (0.56) |

| Transverse lie | 1 (1.0) | 1 (1.0) | 2 (1.0) | 0.001 (0.99) |

| More than one indication | 8 (8.0) | 6 (6.0) | 14 (7.0) | 0.29 (0.59) |

| Total | 100 (100) | 100 (100) | 200 (200) |

CS: cesarean section; T1: leading twin; PPROM: preterm premature rupture of fetal membranes.

The primary and secondary outcome measures are shown in Table 3. The mean blood loss in participants receiving tranexamic acid was significantly lower than in placebos (442.94 ± 200.97 versus 801.28 ± 258.68 mL; p = 0.001). Although, there was no significant difference in the mean preoperative hemoglobin in participants receiving tranexamic acid and controls (11.24 ± 0.88 versus 11.15 ± 0.90 g/dL; p = 0.457), the mean postoperative hemoglobin in participants receiving tranexamic acid was significantly higher in tranexamic acid group than in controls (10.39 ± 0.96 versus 9.67 ± 0.86 g/dL; p = 0.001). Significantly less proportion of participants in the tranexamic acid group than in control group (39.0% versus 68.0%; p = 0.001) required additional uterotonic agent after routine management of the third stage of labor. The incidence of PPH was significantly lower in tranexamic acid group than in controls (1.0% versus 19.0%; p = 0.001). This is shown in Table 4.

Table 3.

Comparison of blood loss during CS in women at high risk of PPH in both groups.

| Tranexamic M + SD |

Placebo M + SD |

t (p value) | Lower CI | Upper CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All groups | |||||

| EBL from gross equation (mL) | 442.94 + 200.97 | 801.28 + 258.68 | 10.92 (<0.01) | 294.46 | 424.26 |

| Preoperative PCV (%) | 33.72 ± 2.63 | 33.44 ± 2.69 | 0.745 (0.457) | 0.461 | 1.021 |

| Postoperative PCV (%) | 31.14 ± 2.88 | 29.00 ± 2.59 | 5.527 (0.001) | 1.346 | 2.904 |

| Preoperative hemoglobin | 11.24 ± 0.88 | 11.15 ± 0.90 | 0.745 (0.457) | 0.154 | 0.340 |

| Postoperative hemoglobin | 10.39 ± 0.96 | 9.67 ± 0.86 | 5.527 (0.001) | 0.459 | 0.968 |

| Mean hemoglobin | 10.83 ± 0.88 | 10.41 ± 0.85 | 3.287 (0.001) | 0.161 | 0.645 |

| Preterm | |||||

| EBL from gross equation (mL) | 439.78 ± 261.98 | 853.41 ± 306.95 | 4.23 (<0.01) | −613.605 | −214.865 |

| Preoperative PCV (%) | 34.53 ± 3.11 | 32.94 ± 2.34 | 1.71 (0.096) | −0.30 | 3.47 |

| Postoperative PCV (%) | 31.82 ± 3.68 | 28.39 ± 2.55 | 3.23 (0.003) | 1.27 | 5.60 |

| Preoperative hemoglobin | 11.51 ± 1.03 | 10.98 ± 0.78 | 1.71 (0.096) | −0.10 | 1.16 |

| Postoperative hemoglobin | 10.61 ± 1.23 | 9.46 ± 0.85 | 3.23 (0.003) | 0.42 | 1.87 |

| Mean hemoglobin | 11.07 ± 1.12 | 9.69 ± 2.53 | 2.06 (0.048) | 0.01 | 2.73 |

| Term | |||||

| EBL from gross equation (mL) | 443.71 ± 118.06 | 791.71 ± 249.77 | 10.11 (<0.01) | −415.912 | −280.08 |

| Preoperative PCV (%) | 33.55 ± 2.51 | 33.55 ± 2.76 | 0.01 (0.99) | −0.80 | 0.82 |

| Postoperative PCV (%) | 31 ± 2.69 | 29.13 ± 2.6 | 4.53 (0) | 1.05 | 2.68 |

| Preoperative hemoglobin | 11.18 ± 0.83 | 11.18 ± 0.92 | 0.01 (0.99) | −0.27 | 0.27 |

| Postoperative hemoglobin | 10.33 ± 0.9 | 9.71 ± 0.87 | 4.53 (0) | 0.35 | 0.89 |

| Mean hemoglobin | 10.78 ± 0.84 | 10.43 ± 0.89 | 2.57 (0.01) | 0.08 | 0.61 |

PPH: postpartum hemorrhage; SD: standard deviation CI: confidence interval; EBL: estimated blood loss; PCV: pack cell volume.

Table 4.

Comparison of the effect of uterotonics among the two groups.

| Variable | Tranexamic | Placebo | Total | χ2 (p value) | RR ratio | CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||||

| Additional uterotonics | ||||||

| Yes | 39 (39.0) | 68 (68.0) | 107 (53.5) | 16.903 (0.001) | 0.57 | 0.43–0.75 |

| No | 61 (61.0) | 32 (32.0) | 93 (46.5) | |||

| EBL | ||||||

| Blood loss >1000 mL | 1 (1.0) | 19 (19.0) | 20 (10.0) | 16.056 (0.001) | 0.05 | 0.01–0.38 |

| Blood loss <1000 mL | 99 (99.0) | 81 (81.0) | 180 (90.0) | |||

| Hemorrhage | 40 (40) | 67 (67) | 107 (53.5) | 14.65 (0.0001) | 0.59 | 0.45–0.78 |

| No hemorrhage | 60 (60) | 33 (33) | 93 (46.5) | |||

RR: relative risk; CI: confidence interval; EBL: estimated blood loss.

Those in the tranexamic acid group had a lower incidence of blood transfusion (39 versus 68) than for the placebo group (p = 0.001) with a CI −0.15 to 0.34. There was no statistical difference in those who had additional interventions in both groups. One woman each from both groups had hysterectomy while two participants in the study group and four in the placebo had B-Lynch procedures. This is shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Comparison of those who received blood transfusion and other surgical interventions among the two groups.

| Variable | Tranexamic | Placebo | Total | χ2 (p value) | RR ratio | CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||||

| Blood transfusion | ||||||

| Yes | 8 (8) | 26 (26) | 34 (17.0) | 10.24 (0.001) | 4 | 1.33–2.21 |

| No | 92 (92) | 74 (74) | 166 (83.0) | |||

| Hysterectomy | ||||||

| Yes | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 2 (1.0) | 0.001 (0.99) | 1 | 0.25–1.86 |

| No | 99 (99) | 99 (99) | 198 (99.0) | |||

| B-Lynch | ||||||

| Positive | 2 (2) | 4 (4) | 6 (3.0) | 0.17 (0.68) | 2.04 | 0.75–2.41 |

| Negative | 98 (98) | 96 (96) | 194 (97.0) | |||

RR: relative risk; CI: confidence interval.

The side effects of the interventions between the two groups are shown in Table 6. There was no reported major side effect between the two groups. There was no significant difference in the incidence of mild side effects in participants receiving tranexamic acid compared to controls (6.0% versus 6.0%; p = 1.000). Almost all the side effects were related to the patient’s background health condition or linked to a possible side effect of another drug. Only six women had these mild effects in the study group while five women also had similar complaints in the placebo group. The binary logistic regression predicting hemorrhage by various factors is shown in Table 7.

Table 6.

Comparison of side effects between the two groups.

| Variable | Tranexamic | Placebo | Total | χ2 (p value) | RR ratio | CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||||

| Side effect | ||||||

| No side effect | 94 (94) | 94 (94) | 94 (94.0) | 4.82 (0.31) | 0.72–2.05 | |

| Dizziness | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 2 (2.0) | |||

| Headache | 3 (3) | (0) | 3 (3.0) | |||

| Nausea | 1 (1) | (0) | 1 (1.0) | |||

| Vomiting | 0 (0) | (0) | 1 (1.0) | |||

RR: relative risk; CI: confidence interval.

Table 7.

Binary logistic regression predicting hemorrhage by various factors.

| Wald | Sig. | Exp(B) | Lower CI | Upper CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic | |||||

| Group (tranexamic) | 15.73 | <0.01* | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.31 |

| Age | 0.50 | 0.48 | 0.96 | 0.85 | 1.08 |

| Gravidity | 0.20 | 0.66 | 1.10 | 0.71 | 1.71 |

| Booking status (booked) | 0.23 | 0.63 | 0.75 | 0.23 | 2.46 |

| Gestational age (term) | 0.25 | 0.62 | 0.66 | 0.12 | 3.48 |

| BMI | 0.03 | 0.87 | 1.01 | 0.88 | 1.17 |

| Indications (positive) | |||||

| Preoperative PCV (continuous variable) | 42.37 | <0.01* | 0.29 | 0.20 | 0.42 |

| Breech | 0.08 | 0.78 | 1.28 | 0.23 | 7.14 |

| Delayed labor stage | 5.54 | 0.02* | 18.18 | 1.62 | 203.39 |

| Two or more CS | 0.10 | 0.75 | 1.32 | 0.24 | 7.32 |

| Lower-segment fibroid | 0.15 | 0.70 | 1.55 | 0.17 | 14.56 |

| Placenta previa | 4.18 | 0.04 | 8.22 | 1.09 | 61.91 |

| Macrosomia | 0.22 | 0.64 | 0.56 | 0.05 | 6.53 |

| Hypertension | 0.52 | 0.47 | 3.84 | 0.10 | 149.97 |

| Multiple gestations | 2.83 | 0.09 | 10.92 | 0.67 | 177.13 |

| Preeclampsia/eclampsia | 0.63 | 0.43 | 0.45 | 0.06 | 3.25 |

| Cord/hand prolapse | 0.48 | 0.49 | 2.69 | 0.16 | 44.58 |

| PROM | 0.18 | 0.67 | 5.34 | 0.00 | 12,724.02 |

| Fetal demise | 1.03 | 0.31 | 29.83 | 0.04 | 21,146.18 |

| Others | 0.08 | 0.78 | 1.26 | 0.27 | 5.94 |

| Constant | 36.20 | <0.01 | 11 × 1020 | ||

CI: confidence interval; BMI: body mass index; PCV: pack cell volume; CS: cesarean section; PROM: premature rupture of fetal membranes. Bold and asterisked values indicate significant at p<0.05.

Discussion

Interestingly, the principal findings of this study were that the mean blood loss, the need for an additional uterotonic agent after routine management of the third stage of labor, and the incidence of PPH in participants receiving tranexamic acid were significantly lower than in placebos but have significantly higher mean postoperative hemoglobin. Although there were no reported major side effects, there was no significant difference in the incidence of mild side effects between the two groups. This was similar to the finding in various other studies, such as the one done by the WOMAN trial, Abdel-Aleem et al., and the Clinical Randomization of an Antifibrinolytic in Significant Hemorrhage (CRASH) 2 trial.7,11,12 Although most of these studies were not done in women at high risk of PPH, this work also demonstrated a significant difference in reducing intraoperative blood loss among women at high risk of PPH. Also, Cheema et al. 1 in an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs on tranexamic acid for the prevention of blood loss after CS concluded that tranexamic acid might lower the chance of blood loss during cesarean deliveries, with a greater benefit seen in high-risk patients, but the lack of reliable data prevents drawing any firm conclusions.

This study had also revealed that the mean postoperative hemoglobin in participants receiving tranexamic acid was significantly higher in tranexamic acid group than in placebos (10.39 ± 0.96 versus 9.67 ± 0.86 g/dL; p = 0.001) and a CI of 0.46–0.96 as observed after 48 h. This was also demonstrated by various other studies, such as the CRASH 2, 12 WOMAN trial, 7 and Riana Van Der Linde et al., 13 and WHO updated recommendations on tranexamic acid for the treatment of postpartum hemorrhage in 2017. 14 Shalaby et al. 2 in a similar study demonstrated that postoperative hematocrit and hemoglobin were both lower (9.2 ± 1.6 and 27.4 ± 4.1 versus 10.1 ± 1.2 and 30.1 ± 3.4; p < 0.001 and 0.012, respectively) and their change percentages were higher (15.41% versus 7.11%, p = 0.001) in the placebo group than in the tranexamic acid group.

Third stage of labor requires prophylactic administration of uterotonics to prevent PPH. Interestingly, in this study, a significantly lower proportion of participants in the tranexamic acid group than in the placebo group (39.0% versus 68.0%; p = 0.001) required additional uterotonic agent after routine management of the third stage of labor. This was similar to the work done by Gungorduk et al. 15 that demonstrated a reduction of the need for additional uterotonics; even though the 39 women in the tranexamic acid group who received the uterotonic agents could have been less but for the fact that it has become the standard for use of uterotonics during cesarean delivery to prevent PPH, most of them might have been given out of anxiety and caution. Again, considering the fact that the participants were women at high risk of PPH, some of them received it out of extreme caution.

One of the goals of intrapartum intervention was to lower the incidence of PPH. In this study, the incidence of PPH was significantly lower in tranexamic acid group than in placebos (1.0% versus 19.0%; p = 0.001). This finding was comparable to few other studies by Abdel-Aleem et al. 11 and Bhatia et al., 16 though most were not high-risk women for PPH. In addition, this finding was similar to a recent meta-analysis involving 18 randomized control trials by Franchini et al. 5 that concluded that the use of tranexamic acid compared to controls (placebo or no intervention) reduced the incidence of PPH (risk ratio 0.40, 95% CI 0.24–0.65; 786 participants).

Blood transfusion is usually an emergency measure to reduce the incidence of shock during primary PPH. There was a statistically significant difference in the need for blood transfusion among the placebo group (26/100) compared to those who received blood transfusion in the study group (8\100) women, p = 0.001. This was similar to the findings of Franchini and other workers.5,17,18 In addition, our study agreed with Wang et al.’s meta-analysis which concluded that the need for blood transfusion was significantly less in the tranexamic acid group than in the control group (RR 0.23, 95% CI 0.10–0.57, p = 0.01). Therefore, our findings demonstrated that the use of tranexamic acid offers an advantage over placebo in reducing the need for blood transfusion during and after CS. However, our findings were contrary to that of Pacheco et al. 3 in a placebo-controlled trial in which they observed a change in hemoglobin level of −1.8 g/dL in the tranexamic acid group when compared to −1.9 g/dL in the placebo group (mean difference, 0.1 g/dL; 95% CI 0.2–0.1). The authors of Pacheco et al. 3 concluded that prophylactic administration of tranexamic acid during cesarean delivery did not reduce the need for blood transfusions. The observed difference from the index study may be due to the difference in the timing of administration of the prophylactic tranexamic acid. They administered the drug after umbilical cord clamping compared to 10 min prior to the onset of surgery in our study.

In this study, there were minor side effects of headache, dizziness, and nausea in both groups. There was no reported major side effect between the two groups. There was no significant difference in the incidence of mild side effects in participants receiving tranexamic acid compared to placebos (6.0% versus 6.0%; p = 1.000). This showed that tranexamic acid does not cause adverse drug reactions even in women at high risk of PPH. Similar reports were obtained in the WOMAN trial, 7 CRASH 2 trial, 12 in a study by XU and colleagues, 19 and Abdel-Aleem and co-workers. 11 However, there were more recorded side effects in women who received tranexamic acid in Abdel-Aleem’s study probably due to different study geographical locations. This varied slightly in this study as there were six women from the study group who had minor side effects of headache, nausea, and dizziness and five women who had similar side effects in the placebo group. It was interesting to note that these women who had the side effects which cut across the two groups, had background health conditions such as severe preeclampsia and eclampsia. Those who had headaches could have been spinal headaches arising from the spinal anesthesia or the dizziness could have been as a result of the high blood pressure. There was no reported case of thromboembolism which has been reported in other studies to be rare and not associated with low-dose tranexamic acid or admission into the ICU. 6 Ogunkua et al 20 in their study also showed that when compared to the placebo, there was no evidence that women who got tranexamic acid had an elevated risk of complications.

Finally, there was no statistically significant in the other interventions, such as hysterectomy, B-Lynch procedure, tubal ligation, and uterine artery ligation though not reported. In the study group, one person had total abdominal hysterectomy while two women had hysterectomies in the placebo group. The other procedures such as tubal ligation were collateral interventions for women who had completed their family size.

The strengths of the study were that this study was a randomized double-blind (both the outcome assessors and the participants were blinded) placebo-controlled in design. The bias from incomplete blinding of the research team members and the performance bias from almost indistinguishable packaging of the tranexamic acid and placebo were significantly reduced by complete blinding of the outcome assessors. This was achieved by labeling the syringes using a coded number written by an independent pharmacist such that only the pharmacist knew the content of the syringes and only decoded the numbers to the researcher at the end of the study. Unlike in previous randomized studies, this study recruited only women who were at high risk of PPH, as recommended by a recent Cochrane review.

The limitation of the study was that the complete elimination of liquor in the measured blood loss was not feasible. This was because the gross equation made use of the weight of the patient in which liquor was part of it. Again, the surgeries performed by different categories of Doctors with different levels of surgical skills might have contributed to bias in the study findings. However, this could have been balanced by the randomization employed in the patient’s recruitment. In addition, we could not evaluate the long-term side effects of tranexamic acid.

Conclusion

Prophylactic administration of tranexamic acid significantly decreases postpartum blood loss, improves postpartum hemoglobin, decreases the need for additional uterotonics, and prevents PPH following CS in pregnant women at high risk of PPH. The use of low-dose tranexamic acid may be recommended for every woman with no contraindication undergoing both elective and emergency CS. There should be a generous use of tranexamic acid, especially in low- and middle-income countries to reduce the burden and costs of blood and the risks associated with blood transfusions.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the participants, ESUT Teaching Hospital, and everyone who participated in the study.

Footnotes

ORCID iDs: George U Eleje  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0390-2152

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0390-2152

Chigozie G Okafor  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4458-8216

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4458-8216

Declarations

Ethical Consideration and Consent to Participate: The approval for the study protocol was obtained on 21 August 2020 from the Ethics Review Committee of ESUT Teaching Hospital, Parklane, Enugu, Nigeria (Reference no. ESUTHP/C-MAC/RA/034/VOL.1/259). The study was conducted based on the ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects according to the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided informed written consent to participate in the study.

Consort statement: This study adhered to the CONSORT guidelines. 21

Consent for publication: The consent for publication was obtained from the participants.

Author contribution(s): Kelvin E Ortuanya: Conceptualization; Data curation; Methodology; Writing—original draft; Writing—review & editing.

George U Eleje: Methodology; Supervision; Writing—original draft; Writing—review & editing.

Frank O Ezugwu: Supervision; Writing—original draft; Writing —review & editing.

Boniface U Odugu: Methodology; Supervision; Writing—original draft; Writing—review & editing.

Joseph I Ikechebelu: Formal analysis; Methodology; Writing—original draft; Writing—review & editing.

Emmanuel O Ugwu: Methodology; Supervision; Writing—original draft; Writing—review & editing.

Ahizechukwu C Eke: Formal analysis; Methodology; Writing—original draft; Writing—review & editing.

Fredrick I Awkadigwe: Formal analysis; Methodology; Writing —original draft; Writing—review & editing.

Malachy N Ezenwaeze: Formal analysis; Methodology; Writing —original draft; Writing—review & editing.

Ifeanyichukwu J Ofor: Formal analysis; Methodology; Writing—original draft; Writing—review & editing.

Chidinma C Okafor: Formal analysis; Methodology; Writing—original draft; Writing—review & editing.

Chigozie G Okafor: Formal analysis; Methodology; Writing—original draft; Writing—review & editing.

Author Declaration: All authors contributed significantly to the conceptualization and design of the study, data collection, data analysis and interpretation, drafting and revision of the article, and final approval of the submitted version. This article has not been submitted to another journal for publication.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Availability of data and materials: The data used to support the findings of this work are available on request from the authors.

References

- 1. Cheema HA, Ahmad AB, Ehsan M, et al. Tranexamic acid for the prevention of blood loss after cesarean section: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM 2023; 5: 101049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Shalaby MA, Maged AM, Al-Asmar A, et al. Safety and efficacy of preoperative tranexamic acid in reducing intraoperative and postoperative blood loss in high-risk women undergoing cesarean delivery: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022; 22: 201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pacheco LD, Clifton RG, Saade GR, et al. Tranexamic acid to prevent obstetrical hemorrhage after cesarean delivery. N Engl J Med 2023; 388(15): 1365–1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pacheco LD, Hankins GDV, Saad AF, et al. Tranexamic acid for the management of obstetric hemorrhage. Obstetric Gynecol 2017; 130: 765–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Franchini M, Mengoli C, Cruciani M, et al. Safety and efficacy of tranexamic acid for prevention of obstetric haemorrhage: an updated systemic review and meta-analysis. Blood Transfus 2018; 16(4): 329–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Novikova N, Hofmeyr GJ, Cluver C. Tranexamic acid for preventing postpartum haemorrhage. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015; 6: CD007872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shakur -Still H, Elbourne D, Gülmezoglu A, et al. The WOMAN Trial (World Maternal Antifibrinolytic Trial): tranexamic acid for the treatment of postpartum haemorrhage: an international randomised, double blind placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2017; 389: 2105–2116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sehat KR, Evans RL, Newman JH. Hidden blood loss following Hip and Knee arthroplasty. Correct management of blood Loss should take hidden loss into account. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2004; 86(4): 561–565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shein-Chung C, Jun S, Hansheng W, et al. Sample size calculations in clinical research. In : Textbook on biostatistics, 3rd ed., Boca Raton, FL; London; New York: Tayor and Francis Group, 2008, p.13. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Aly AH, Ramadani HM. Assessment of blood loss during caesarean section under general anaesthesia and epidural analgesia using different methods. Alex J Anaesth Intensive Care 2006; 9(1): 35–34. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Abdel-Aleem H, Alhusaini TK, Abdel-Aleem MA, et al. Effectiveness of tranexamic acid on blood loss in patients undergoing elective caesarean section: randomized clinical trial. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2013; 26(17): 1705–1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Roberts I, Shakur H, Coats T, et al. The CRASH-2 trial: a randomized controlled trial and economic evaluation of the effects of tranexamic acid on death, vascular occlusive events and transfusion requirement in bleeding trauma patients. Health Technol Assess 2013; 17(10): 1–79.\ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Van Der Linde R, Favaloro EJ. Tranexamic acid to prevent post-partum haemorrhage. Blood Transfus 2018; 16(4): 321–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. World Health organization. Updated WHO recommendations on Tranexamic Acid for the treatment of Postpartum haemorrhage. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health organization, 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gungorduk K, Yildirim G, Asicioglu O, et al. Efficacy of intravenous tranexamic acid in reducing blood loss after elective caesarean section: a prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Am J Perinatol 2011; 28(3): 233–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bhatia SK, Deshpande H. Role of tranexamic acid in reducing blood loss during and after caesarean section. Med J DY Patil Univ 2015; 8: 21–25. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lakshmi SD, Abraham R. Role of prophylactic tranexamic acid in reducing blood loss during elective caesarean section: a randomized controlled study. J Clin Diagn Res 2016; 10(12): QC17–QC21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wang HY, Hong SK, Duan Y, et al. Tranexamic acid and blood loss during and after caesarean section: a meta-analysis. J Perinatal 2015; 35(10): 818–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Xu J, Gao W, Ju Y. Tranexamic acid for the prevention of postpartum haemorrhage after caesarean section: a double-blind randomization trial. Arch Gynaecol Obstet 2013; 287(3): 463–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ogunkua OT, Duryea EL, Nelson DB, et al. Tranexamic acid for prevention of hemorrhage in elective repeat cesarean delivery-a randomized study. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM 2022; 4(2): 100573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Falci SG, Marques LS. CONSORT: when and how to use it. Dental Press J Orthod 2015; 20(3): 13–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]