Abstract

A trivalent (feline panleucopenia, feline herpesvirus, feline calicivirus), modified live, commercially available cat vaccine was used at either 6, 9 and 12 weeks of age (early schedule) or 9 and 12 weeks of age (conventional schedule), and the serological response to vaccination was assessed. The level of maternally derived antibody present at 6 weeks of age was also established. The use of early vaccination at 6 weeks of age induced an antibody response to each virus by 9 weeks of age in a significant proportion of kittens compared with unvaccinated littermates. There was no difference between the conventionally and early-vaccinated groups in terms of antibody response to any antigen by 12 and 15 weeks of age.

Although vaccination against feline panleucopenia virus (FPLV), feline herpes-virus (FHV-1, also known as feline viral rhinotracheitis or FVR) and feline calicivirus (FCV) has been available in the UK for many years, these infectious agents remain common causes of morbidity and mortality in cats. This reflects the epidemiology of these diseases, where the carrier cat is important in transmission of the respiratory viruses (FHV-1 and FCV), and the persistence of FPLV in the environment allows continued exposure on infected premises (Gaskell 1994, Gaskell & Dawson 1994).

Surveys on the prevalence of FHV-1 and FCV in the general cat population carried out both prior to the introduction of vaccination (Wardley et al 1974) and subsequently (Coutts et al 1994) have demonstrated little change over that period for both FCV (24–25%) and FHV-1 (1–2%). As FCV carriers shed virus continuously, the majority of these healthy positive cats are likely to be carriers. In contrast, for FHV-1, where the virus is predominantly latent and shed mainly after stress, it is probable that a greater number of cats were FHV-1 carriers but were not actively shedding virus at the time of sampling. These carrier cats in the feline population provide an important source of virus to susceptible kittens. Where these viruses are endemic in a household (or other facility, such as a rescue shelter), disease is most often seen in young kittens around the time they lose their maternally derived antibody (MDA). Previous reports suggest that FHV-1 MDA may persist for 2–10 weeks, and for FCV, MDA may persist for 10–14 weeks (Slater & York 1975, Gaskell & Povey 1982, Johnson & Povey 1983, 1985), but this has not been widely studied.

Feline panleucopenia (feline infectious enteritis) is caused by a feline parvovirus (FPLV). It is now a relatively uncommon disease, probably due to the widespread use of effective vaccines. However, it has been suggested that in recent years, the number of feline panleucopenia cases may be increasing (Addie et al 1998). As the virus is very resistant to disinfection, once a case of panleucopenia has occurred, the environment may remain contaminated for a considerable time. Therefore, any gap between the waning of MDA and vaccination in a contaminated household is likely to lead to disease in kittens. MDA in cats declines with a half-life of 9.5 days and, for FPLV, in most cases has declined to non-interfering levels by 8–12 weeks of age (Scott et al 1970). However, in certain situations, eg where MDA is likely to be low, or there is a high challenge dose of FPLV in the environment, MDA levels may be inadequate and disease may result.

Although conventional vaccination at 9 and 12 weeks of age has previously been shown to provide protection in the majority of cases against FHV-1-, FCV- and FPLV-induced disease, in some situations, an earlier vaccination schedule may be desirable. Previous studies on FCV and FHV have also suggested that an earlier vaccination schedule may be helpful (Slater & York 1975; Johnson & Povey 1985), although these have been laboratory-based studies. This field study was therefore set up to try to assess whether earlier vaccination, at 6 weeks of age, would be successful in inducing serological response, and therefore hopefully prevent disease from occurring, prior to conventional vaccination. The vaccine used was a commercially available, systemically administered, modified live trivalent vaccine. The objectives of the trial were two-fold: to determine the level of MDA to FHV-1, FCV and FPLV in 6-week-old kittens; and to compare the antibody responses of an ‘early’ vaccination regimen (at 6, 9 and 12 weeks of age) to a ‘conventional’ vaccine regimen (at 9 and 12 weeks of age) at different timepoints post-vaccination (9, 12 and 15 weeks of age).

Materials and methods

Trial sites

Ten centres were selected as trial sites: five rescue catteries, four breeding catteries and one private household fostering rescue kittens. The respiratory and enteric disease status of each site was assessed and classified as current (present within last 4 weeks), non-current (present more than 5 weeks ago) and none (no history of disease).

Cats and kittens

Apparently healthy queens with litters of two or more kittens were recruited for the trial. When the litter was 3–4 weeks old, queens were screened, by commercial ELISA, for feline leukaemia virus (FeLV) antigen and for antibody to feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV). The litter was excluded if the queen was positive for either virus. Kittens were withdrawn if any signs of respiratory disease, enteritis or other disease developed.

The first kitten of each litter was assigned at random (by tossing a coin) to group A or B, and the remainder of the litter alternated between these groups. Group A kittens were vaccinated at 6, 9 and 12 weeks of age and group B were vaccinated at 9 and 12 weeks of age. The vaccine used for group A had a higher release titre for FCV and FPLV than that for group B (Table 1).

Table 1.

Vaccine batch numbers and virus titres

| Group A | Group B | |

|---|---|---|

| Batch number | 9405 | 9417B |

| FHV-1 titre | 106.2 TCID50 | 106.2 TCID50 |

| FCV | 106.6 TCID50 | 105.6 TCID50 |

| FPLV | 106.0 TCID50 | 105.1 TCID50 |

FHV-1, feline herpesvirus; FCV, feline calicivirus; FPLV, feline panleucopenia virus.

Sampling methods

All kittens were bled by jugular venipuncture at 6, 9, 12 and 15 weeks for FCV, FHV-1 and FPLV serology. Oronasal and rectal swabs were taken into virus transport medium (VTM) [Eagles MEM with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), 100 υg/ml ml streptomycin, 100 IU penicillin, buffered with sodium bicarbonate] for virus isolation prior to primary vaccination. Samples were stored below −50°C prior to processing. Virus isolation was performed by standard methods (Coutts et al 1994). All sera were heat inactivated (56°C/30 min) prior to testing. Antibodies to FCV were determined by a constant virus varying sera dilution neutralisation test (Johnson & Povey 1983) in 96-well microtitre plates using five wells per serum dilution. The FHV-1 serology was performed by indirect immunofluorescence antibody assay. Basically, four-fold dilutions (100 μl volumes) of each serum sample were added to a 96-well plate (two wells per dilution) containing alcohol-fixed FHV-infected CRFK cells. They were incubated at 37°C for 1 h, washed, then overlaid with FITC-conjugated anti-FHV serum. After a further hour's incubation at 37°C, each well was observed and scored positive if fluorescent foci were observed. The antibody titre was calculated by the method of Reed & Meunch (1938). FPLV antibodies were measured by HAI test as per Churchill (1982) but using a pH 6.5 buffer solution.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SSPS 8.0 and gee S-function, version 4.13. The response rate (four-fold or greater rise from an earlier titre) at 9, 12 and 15 weeks to ‘early’ and ‘conventional’ vaccination was compared and presented as an odds ratio which was analysed by the Fisher's exact test. For the FHV-1 analysis, where there was a previous titre of less than one in four at 6 weeks, a later titre of one in eight was taken as a responder. In a further analysis, carried out where group numbers were sufficient, the odds ratio was adjusted to accommodate the correlation in responses observed within litters (clusters). The odds ratio derived from this generalised estimating equation model (Liang & Zeger 1986) was analysed by the Wald test. All tests were two-tailed with significance set at P < 0.05.

Results

Thirty-five queens and 137 kittens were enrolled at 4–5 weeks of age. Only 68 kittens completed the trial as there was a higher than expected dropout rate. These 68 kittens were from 10 different households. Forty-five of the kittens were in one of five rescue shelters, the remaining 23 kittens were from the four breeding households and the private household. All the kittens at the rescue shelters were either short-haired or long-haired domestic cats. The 23 kittens in the private households comprised 13 British Short-hairs, four Korats, two Persians and three Persian-crosses.

Reasons for exclusion

Reasons for exclusion included FIV-positive queens, respiratory disease present in the kittens, and sudden death, including suspected or confirmed panleucopenia, in some litters of kittens. All the rescue shelters had reported respiratory or gastrointestinal disease in cats at the shelter either prior to the trial, during the trial or both. One rescue centre suffered a high level of morbidity and mortality in kittens around 6 weeks of age which proved impossible to follow-up; this shelter was withdrawn from the study. Three of the five breeding households reported a history of or current respiratory disease, and FCV was isolated from one household. A small proportion of kittens were lost to follow-up at 15 weeks (due to rehoming), and in some kittens insufficient serum was obtained for all tests.

MDA levels at 6 weeks of age

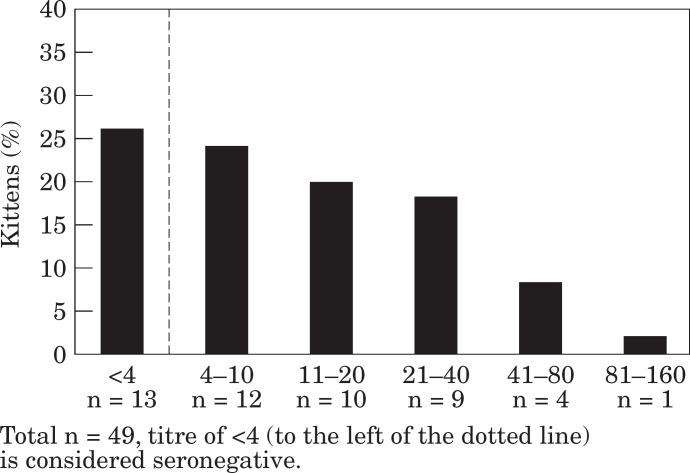

For FHV-1, although 68 kittens completed the trial, usable data was only available for 49 kittens. Titres ranged from less than one in four (n=13) to one in 128 (n=1) with a geometric mean titre of approximately one in eight (Fig 1).

Fig 1.

Maternally derived antibody levels to feline herpes-virus at 6 weeks of age.

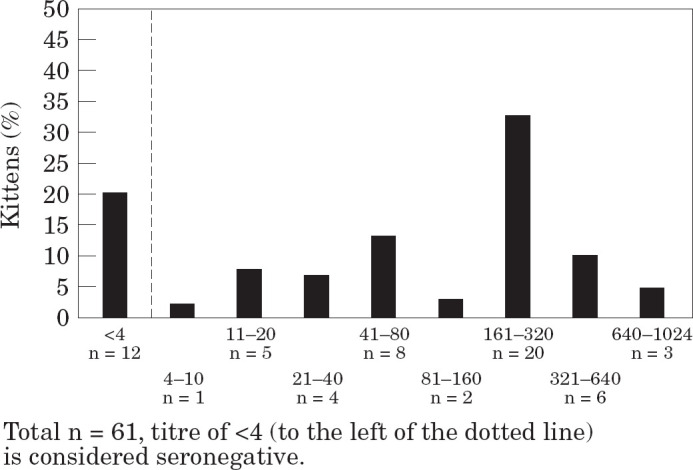

For FCV, usable data was available for 61 kittens. Titres ranged from less than one in four (n=12) to one in 1024 (n=1), with a geometric mean of approximately one in 64 (Fig 2).

Fig 2.

Maternally derived antibody levels to feline calici-virus at 6 weeks of age.

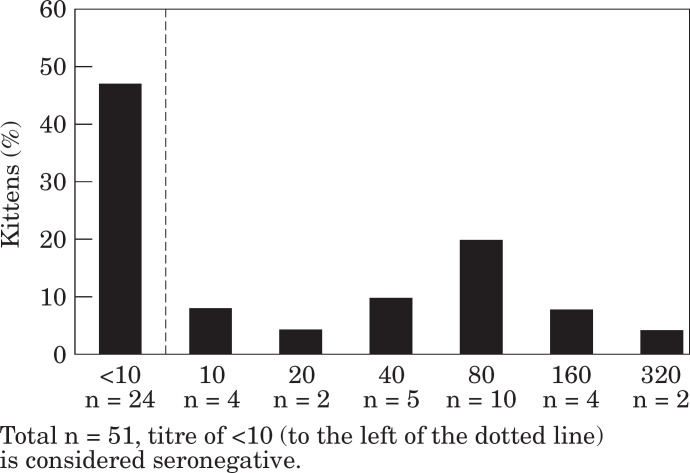

For FPLV, usable data was available for 51 kittens. Titres ranged from less than one in 10 (n=24) to one in 320 (n=2), with a geometric mean of approximately one in 16 (Fig 3).

Fig 3.

Maternally derived antibody levels to feline panleucopenia virus at 6 weeks of age.

Response rate of ‘early’ vaccinated kittens compared with ‘conventionally’ vaccinated kittens

The proportion of kittens responding in each group at different timepoints for each of the three viruses is shown in Table 2. The response rates for only those kittens that were seronegative at 6 weeks of age is shown in Table 3. The early-vaccinated kittens showed significantly better response rates to all three viruses at 9 weeks of age compared with the conventionally vaccinated (i.e. unvaccinated) kittens, although for FCV in particular, numbers were small, and statistical analysis was therefore limited. This demonstrates that kittens can respond to early vaccination as measured by serological response.

Table 2.

Response rates for all kittens in early- and conventionally vaccinated groups

| Virus | Group | 9 weeks of age | 12 weeks of age | 15 weeks of age |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FHV-1 | Early vacc. | 9/20 (45%) * | 18/26 (69%) | 23/24 (96%) |

| Con. vacc. | 1/20 (5%) * | 11/22 (50%) | 16/20 (80%) | |

| FCV | Early vacc. | 3/24 (12.5%) | 8/24 (33%) | 11/21 (52%) |

| Con. vacc. | 0/25 (0%) | 8/20 (40%) | 13/22 (59%) | |

| FPLV | Early vacc. | 8/19 (42%) † | 9/20 (45%) | 11/18 (61%) |

| Con. vacc. | 0/22 (0%) † | 10/19 (53%) | 12/16 (75%) |

Early vacc, early-vaccinated group (group A) vaccinated at 6, 9 and 12 weeks of age; Con. vacc, conventionally vaccinated group (group B) vaccinated at 9 and 12 weeks of age.

Significant difference between early- and conventionally vaccinated groups on Fisher's exact test and GEE analysis (Wald test).

Significant difference between early- and conventionally vaccinated groups on Fisher's exact test.

FHV-1, feline herpesvirus; FCV, feline calicivirus; FPLV, feline panleucopenia virus.

Table 3.

Response rates for kittens seronegative at 6 weeks of age † in the early- and conventionally vaccinated groups

| Virus | Group | 9 weeks of age | 12 weeks of age | 15 weeks of age |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FHV-1 | Early vacc. | 3/7 (43%) | 8/8 (100%) | 8/8 (100%) |

| Con. vacc. | 1/6 (17%) | 3/6 (50%) | 4/6 (67%) | |

| FCV | Early vacc. | 3/3 (100%) * | 3/3 (100%) | 3/3 (100%) |

| Con. vacc. | 0/4 (0%) * | 2/4 (40%) | 3/3 (100%) | |

| FPLV | Early vacc. | 7/8 (88%) * | 7/8 (88%) | 7/8 (88%) |

| Con. vacc. | 0/13 (0%) * | 9/13 (69%) | 9/10 (90%) |

Early vacc, early-vaccination group (group A) vaccinated at 6, 9 and 12 weeks of age; Con. vacc, conventionally vaccinated group (group B) vaccinated at 9 and 12 weeks of age.

Significant difference between early- and conventional-vaccinated groups on Fisher's exact test.

Seronegative for FHV was ≤4; for FCV <4; for FPLV <10.

FHV-1, feline herpesvirus; FCV, feline calicivirus; FPLV, feline panleucopenia virus.

Comparison of the responses of the early vaccination group at 12 weeks of age and the conventional vaccination group at 15 weeks of age (when both groups had received two doses) showed that the conventional vaccination schedule tended to give a better response at this point. This may be due to interference with early vaccination by MDA in some kittens in the early-vaccine group. However, responses in the two groups were similar by 15 weeks of age, when both groups had completed their vaccination schedule.

Discussion

MDA levels in 6-week-old kittens

Other workers have suggested that early vaccination may be beneficial in some circumstances, dependent on the level of MDA in kittens and the rate of decline (Slater & York 1975, Johnson & Povey 1985, Gaskell & Dawson 1994). The current study supports this view, and provides further information on the levels of MDA detected in 6-week-old kittens in a variety of field management situations. In general, similar to previous reports (Slater & York 1975, Gaskell & Povey 1982), the levels of MDA to FHV-1 were low (mean one in eight) at 6 weeks of age. For FCV, MDA levels were higher with a mean titre of one in 64 at 6 weeks of age. Previous studies have also found a relatively long (10–14 weeks) duration of MDA for FCV, implying a higher level of MDA initially (Johnson & Povey 1983). Unexpectedly, the current study demonstrated that almost half the kittens had no detectable MDA to FPLV at 6 weeks of age, and titres were generally low (mean one in 16). FPLV titres in 6-week-old kittens have previously been shown to be much higher (mean one in 100) (Scott et al 1970). This may indicate low likelihood of vaccination or exposure of the queens in this population of largely rescue or pedigree households, and suggests that early vaccination may be highly beneficial in such circumstances.

Response to early vaccination

Where respiratory disease has occurred in a household or colony, early vaccination has been advocated, using either intranasal or systemic routes (Slater & York 1975, Johnson & Povey 1985, Gaskell & Dawson 1994). The use of FPLV vaccines has also been suggested in younger kittens at high risk (Greene 1998), but it must be borne in mind that live FPLV vaccines should not be used in kittens younger than 4 weeks of age due to the possibility of development of cerebellar hypoplasia. Early vaccination is most useful where kittens are likely to be at risk, such as in rescue catteries, or in situations where levels of MDA have declined to non-protective levels before the conventional 9-week primary inoculation. Factors that are important to consider when suggesting the use of an early vaccination include efficacy and safety at this age, and that there should be no interference with a subsequent primary course.

Although numbers in this study were small because of the high dropout rate, and statistical analysis was therefore limited, it was demonstrated that a significant proportion of kittens vaccinated with a trivalent vaccine at 6 weeks of age will respond to vaccination compared with unvaccinated controls, as assessed by the development of a serological response 3 weeks post-vaccination. Such early protection would be of benefit to kittens in a situation where they are likely to come into contact with the viruses prior to vaccination at 9 weeks, such as occurs in rescue shelters and breeding colonies. Further, both groups responded equally by the end of the study in that there was no significant difference in serological response between the early- and conventionally vaccinated groups at 12 and 15 weeks of age.

Although the majority of cats in both groups had responded to all three vaccine viruses by 15 weeks of age, in some kittens there was an apparent lack of response to one or other of the components. However, most kittens had shown a serological response to the other viruses, suggesting they were not immunocompromised. Clearly the vaccine itself was potent, since the majority of cats responded to each component. The most likely explanations are that either low levels of MDA were still present by 9 and 12 weeks, which may have interfered with the response to vaccination, particularly with FCV, or that immunological differences prevented development of measurable antibody to specific antigens.

The kittens in group A and group B were given vaccine of different batches. Slightly higher release titres (Table 1) were given for FCV and FPLV in the 6-week-old group. It is therefore not clear whether the use of the lower titre would be equally effective in overcoming MDA in an early-vaccination schedule. It might be expected that the serological response to the higher titre product repeated three times (ie at 6, 9, and 12 weeks of age) would be superior to the lower titre product given in a conventional schedule; however, there was no difference between the groups at 12 and 15 weeks of age.

In conclusion, this study shows that early vaccination may be useful in situations where an early response to FHV-1, FPLV and FCV vaccination is required, for example in breeding colonies with endemic disease, or in young kittens in rescue catteries where a high risk of disease is expected. Use of an additional earlier vaccine at 6 weeks of age may be particularly helpful where kittens have no or low levels of MDA present at 6 weeks of age.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the owners, staff and veterinary surgeons of the households and shelters involved for their co-operation in the performance of this study, and to Claire Chillingworth at Intervet Laboratories and Chris McCracken and Ruth Ryvar at the University of Liverpool for technical assistance. KW was supported by the Robert Daubney Research Fellowship from the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons Trust Fund and by Intervet Laboratories during the course of this study.

References

- Addie D, Toth S, Thompson H, Greenwood N, Jarrett JO. (1998) Detection of feline parvovirus in dying pedigree kittens. Veterinary Record 142, 353–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Churchill AE. (1982) A potency test for inactivated small animal parvovirus vaccines using chicks. Journal of Biological Standardisation 10, 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coutts AJ, Dawson S, Willoughby K, Gaskell RM. (1994) Isolation of feline respiratory viruses from clinically healthy cats at UK cat shows. Veterinary Record 123, 555–556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaskell RM. (1994) Feline panleucopenia. In: Feline Medicine and Therapeutics (2nd edn) Chandler EA, Gaskell CJ, Gaskell RM. (eds). Blackwell Scientific, Oxford, pp. 445–452. [Google Scholar]

- Gaskell RM, Dawson S. (1994) Viral-induced upper respiratory tract disease. In: Feline Medicine and Therapeutics (2nd edn) Chandler EA, Gaskell CJ, Gaskell RM. (eds). Blackwell Scientific, Oxford, pp. 453–472. [Google Scholar]

- Gaskell RM, Povey RC. (1982) Transmission of feline viral rhinotracheitis. Veterinary Record 111, 359–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene CE. (1998) Feline panleukopenia. In: Infectious Disease of the Dog and Cat (2nd edn), Greene CE. (ed.) W.B. Saunders Company, Philadelphia, pp. 52–57. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RH, Povey RC. (1983) Transfer and decline of maternal antibody to feline calicivirus. Canadian Veterinary Journal 24, 6–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RH, Povey RC. (1985) Vaccination against feline viral rhinotracheitis in kittens with maternally derived feline viral rhinotracheitis antibodies. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 186, 149–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang KY, Zegler SL. (1986) Longitudinal data-analysis using generalised linear models. Biometrika 73, 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Reed LJ, Meunch H. (1938) A simple method of estimating fifty percent endpoints. The American Journal of Hygiene 27, 493–497. [Google Scholar]

- Scott FW, Csiza CK, Gillespie JH. (1970) Maternally derived immunity to feline panleukopenia. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 156, 439–453. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slater E, York C. (1975) Comparative studies on parenteral and intranasal inoculation of an attenuated feline herpes-virus. Developing Biological Standards 33, 410–416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardley RC, Gaskell RM, Povey RC. (1974) Feline respiratory viruses; their prevalence in healthy cats. Journal of Small Animal Practice 15, 579–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]