Abstract

Clinical summary:

A 4-year-old Birman cat was presented with marked obtundation and non-ambulatory tetraparesis. Two well-demarcated, intra-axial T2-hyperintense, T1-hypointense structures, which did not contrast enhance, were evident on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Histopathology of the structures revealed metacestodes that were morphologically indicative of larval stages of Taenia species. Polymerase chain reaction amplification of a fragment within the 12S rRNA gene confirmed the subspecies as Taenia serialis.

Practical significance:

This is the first report of MRI findings of cerebral coenurosis caused by T serialis in a cat. Early MRI should be considered an important part of the diagnostic work-up for this rare clinical disease, as it will help guide subsequent treatment and may improve the prognosis.

Clinical report

A 4-year-old female spayed Birman cat was referred to the Neurology and Neurosurgery Service at the Royal Veterinary College with a 2-day history of progressive obtundation and tetraparesis. The patient was an indoor/outdoor cat residing in an urban environment in a multi-cat household with reptiles and dogs. The cat had no known travel history outside the UK. No treatment was given prior to referral and there was no history of toxin ingestion.

On neurological evaluation the cat was found to be markedly obtunded, non-ambulatory tetraparetic and had multiple cranial nerve deficits. The deficits were bilateral and included reduced menace responses and facial sensation, and positional vertical nystagmus. Based on these findings, the neuroanatomical localisation was diffuse brain. Given the signalment and progression, the most likely differential diagnoses comprised inflammatory, infectious and neoplastic disease.

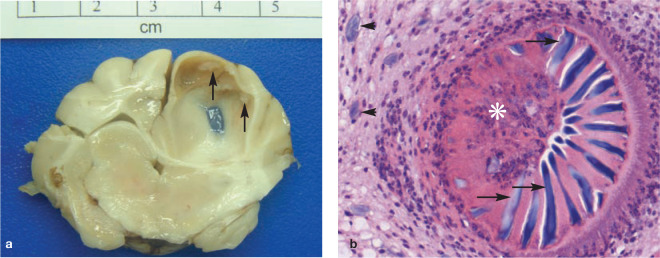

A complete blood count, serum biochemistry and urinalysis were unremarkable. Magnetic resonance (MR) images of the brain were acquired using a 1.5 T superconducting magnet with a human spine coil (Intera 1.5T, Philips Medical Systems, Eindhoven, the Netherlands). Images were obtained in sagittal and transverse planes; sequences included T1-weighted (T1W) and T2-weighted (T2W) turbo spin-echo sequences, fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) and T1W sequences after intravenous administration of gadoterate meglumine (Dotarem; Guerbet, Milton Keynes, UK).

MRI of the brain revealed two well- demarcated, intra-axial cystic structures within the frontal and parietal lobes of the left cerebral hemisphere (Figure 1). The structures were homogeneously T2-hyperintense and T1-hypointense, suppressed on FLAIR and did not demonstrate contrast enhancement. The images also showed midline shift to the right, with marked subfalcian, subtentorial and foramen magnum herniation.

Figure 1.

MRI of a Birman cat infected with the larval stage of Taenia serialis (Coenurus serialis). Sagittal and transverse T2-weighted (a,b), transverse FLAIR (c), transverse T1-weighted (d) and transverse T1-weighted post-contrast (e) images are shown. Two well-demarcated, focal, intra-axial lesions are noted which are T2-hyperintense, T1-hypointense, suppress on FLAIR and show no gadolinium contrast enhancement

Based on the MR images, the differential diagnoses for the cystic lesions were considered to be parasitic disease, primary or metastatic neoplasia or a progressive congenital anomaly. The cat recovered poorly from the general anaesthetic and, due to the grave prognosis, was euthanased.

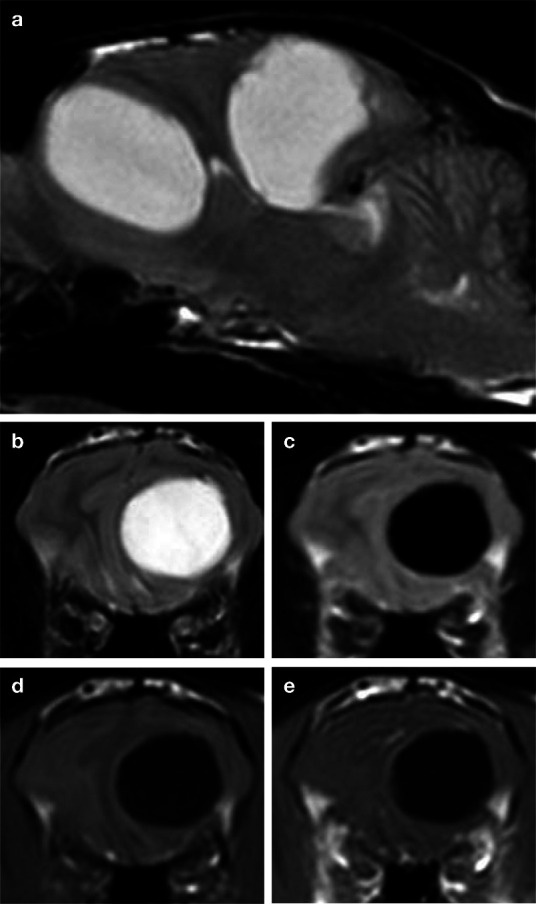

At gross post-mortem examination, the left cerebrum was mildly swollen. The caudal vermis of the cerebellum was elongate and flattened, consistent with herniation of the cerebellar vermis through the foramen magnum (coning). On the dorsal surface of the left parietal lobe a depressed translucent-appearing area measuring approximately 0.5 x 0.5 cm was noted. Sagittal sections through the left cerebral hemisphere revealed two cystic structures, which contained clear fluid. The left cerebral hemisphere enlargement resulted in marked compression of the right cerebrum and left midbrain. The midbrain compression occluded the lumen of the mesencephalic aqueduct (Figure 2), resulting in cerebrospinal fluid accumulation within the right cavity of the olfactory bulb. Small multifocal whitish areas with an irregular surface were observed on the inner aspects of the cysts (Figures 2 and 3), consistent with aggregated scolices of the larval stage of a cystic cestode.

Figure 2.

Cerebral coenurosis in a Birman cat. (a) There is an intraparenchymal cystic structure (black arrow) within the left cerebral cortex, resulting in compression of the right cerebral cortex and midbrain. Small multifocal whitish areas are observed on the inside of the cyst wall (white arrows). (b) Microscopic examination reveals that the cystic structure is formed by a metacestode characterised by an outer cuticle (rectangle) surrounding a parenchymatous body (asterisk); haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain, x 10 magnification

Figure 3.

Cerebral coenurosis in a Birman cat. (a) The inner surface of a large parasitic cyst within the left parietal lobe is multifocally roughened (arrows) corresponding to aggregations of invaginated protoscolices arranged in an approximately linear fashion. (b) Protoscolex (asterisk) showing the rostellum armed with chitinised hooks (arrows). Note the basophilic calcareous corpuscles (arrowheads) in the adjacent parenchyma. H&E stain, x 400 magnification

On histopathology, the compressed brain parenchyma surrounding the cysts showed mild mixed-cellular inflammation with lymphocytes, neutrophils and eosinophils. The histopathology also confirmed the presence of metacestodes. These were characterised by a parenchymatous body with calcareous corpuscles, and the absence of a digestive tract and reproductive organs, and were surrounded by a tegument. Invaginated scolices were noted within the cystic structures (Figures 2 and 3). Morphological features of the cestode larvae were indicative of metacestodes of Taenia species. T serialis was identified as the subspecies following amplification of a cestode-specific 12S rRNA fragment1,2 which gave 100% homology to T serialis (Genbank accession number DQ104236) when blasted against the database.

Discussion

Isolated cases of feline cerebral coenurosis have been described in Australia 3 and North America,4–8 each exhibiting neurological deterioration over 1–2 weeks. One report describes the computed tomographic appearance of a T serialis cyst as being a well-defined hypodense mass with no evidence of contrast enhancement; in the same cat, mildly inflammatory (total nuclear cell count 10/mm3) cerebrospinal fluid was noted. 6 In all cases, diagnosis was made post mortem by detection of the cerebral coenuri with the characteristic scolex.

T serialis normally has a carnivore (final host)–lagomorph (intermediate host) life cycle and it is thought that the metacestode larval stage undergoes aberrant larval migrans to cause cerebral coenurosis. 8 The cat described here presumably developed the infection via faecal–oral inoculation from one of the dogs in the household; however, the exact process of infection has not been studied in the felid.

In the human literature a well-documented condition of neurocysticercosis, caused by the larval stage (metacestode) of Taenia solium (Cysticercus cellulosae), has been described.9–15 It is thought that following a faecal–oral route of inoculation the larva travel in the bloodstream to reach the brain, where they undergo degeneration over a few weeks to several years. 9 The course of infection is characterised by a prolonged asymptomatic period of between 3 and 5 years, while the cysts mature. 10 Once large enough, the cysts may result in clinical signs, such as seizures, secondarily to obstructive hydrocephalus, increased intracranial pressure (ICP), cerebrovascular events (strokes) and encephalitis. 11 In the case reported here, increased ICP causing the subtentorial herniation seen on MRI could explain the cat’s acute progressive deterioration prior to referral.

In general, small live cysts evoke a minimal or an undetectable inflammatory response. The rupture of degenerating cysts is thought to induce the severe inflammatory changes that cause neurological signs. 10 In humans with neurocysticercosis a primary determinant of clinical signs is whether the infection is confined to the brain parenchyma, when seizures are the most common sign. 10 If lesions are extra-axial, clinical signs are mostly associated with intracranial hypertension. 10 If there are numerous intracranial cysts, their degeneration can lead to severe oedema and significantly elevated ICP, causing headache, vomiting, altered sensorium and even death. 9 It is most likely, in the case of this cat, that the increasing volume of the cysts resulted in elevated ICP, parenchymal shift and herniation, leading to rapid neurological deterioration.

Traditionally in canid hosts, the diagnosis of Taenia species infection is based on detection and identification of cestode segments passed in the faeces, or detection of eggs on faecal flotation examination. As MRI provides good soft tissue detail, it is used in human medicine to differentiate neurocysticercosis from other differentials such as tuberculosis, brain abscesses, toxoplasmosis, fungal infections and neoplasia. 10 However, in most cases computed tomography (CT) is used for screening when there is a high index of suspicion for neurocysticercosis as this modality is better than MRI at diagnosing calcified lesions. 13 Based on the rarity of cerebral coenurosis and the possibility of false-negative results with CT, MRI should be considered a much more sensitive and specific diagnostic tool in cats.

Treatment of neurocysticercosis or cerebral coenurosis may be surgical or medical. Surgical management is recommended for intraventricular cysts, and hydrocephalus secondary to neurocysticercosis. 14 In the case of intraventricular cysts, and large parenchymal cysts causing mass effect, the outcome is generally excellent. 14 Based on experiences of treatment in humans, neurosurgical intervention in this cat may have been associated with a high degree of morbidity and risk of mortality due to the multifocal and intraparenchymal nature of the lesions.

In the human literature, medical treatment for live neurocysticercosis involves an initial dose of steroids and frequent dosing of praziquantel or albendazole to reach a maximal peak and to increase compliance. 15 No studies are available on treatment of cerebral coenurosis caused by T serialis in cats. Epsiprantel is approved for use in cats for Taenia species, while praziquantel is approved for use and is highly effective in the treatment of a variety of Taenia species in dogs. However, given the marked clinical signs that this cat was demonstrating it is unlikely that medical management would have been effective.

Conclusion

Familiarity with clinical presentation, combined with diagnostic imaging, may allow early identification of this rare clinical disease and, in turn, instigation of treatment. With regards to treatment for cerebral coenurosis we can only extrapolate from the human literature for neurocysticercosis, which would suggest that surgical management is most likely to be successful for an extra-axial lesion, 14 while medical management is most likely to be effective for early small lesions. 15 Early MRI for T serialis should be considered an important part of the diagnostic work-up, as it will help guide subsequent treatment and may improve the prognosis.

Footnotes

Funding: The authors received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors for the preparation of this case report.

The authors do not have any potential conflicts of interest to declare.

Date accepted: 9 May 2012

References

- 1. Dinkel A, von Nickisch-Rosenegk M, Bilger B, Merli M, Lucius R, Romig T. Detection of Echinococcus multilocularis in the definitive host: coprodiagnosis by PCR as an alternative to necropsy. J Clin Microbiol 1998; 36: 1871–1876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. von Nickisch-Rosenegk M, Silva-Gonzalez R, Lucius R. Modification of universal 12S rDNA primers for specific amplification of contaminated Taenia species (Cestoda) gDNA enabling phylogenetic studies. Parasitol Res 1999; 85: 819–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Slocombe RF, Arundel JH, Labuc R, Doyle MK. Cerebral coenuriasis in a domestic cat. Aust Vet J 1989; 66: 92–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hayes MA, Creighton SR. A coenurus in the brain of a cat. Can Vet J 1978; 19: 341–343. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Georgi JR, De Lahunta A, Percy DH. Cerebral coenurosis in a cat. Report of a case. Cornell Vet 1969; 59: 127–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Smith MC, Bailey CS, Baker N, Kock N. Cerebral coenurosis in a cat. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1988; 192: 82–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kingston N, Williams ES, Bergstrom RC, Wilson WC, Miller R. Cerebral coenuriasis in domestic cats in Wyoming and Alaska. Proc Helm Soc Wash 1984; 51: 309–314. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Huss BT, Miller MA, Corwin RM, Hoberg EP, O’Brien DP. Fatal cerebral coenurosis in a cat. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1994; 205: 69–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rajshekhar V. Surgical management of neurocysticercosis. Int J Surg 2010; 8: 100–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mahanty S, Garcia HH. Cysticercosis and neurocysticercosis as pathogens affecting the nervous system. Prog Neurobiol 2010; 91: 172–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nash TE, Del Brutto OH, Butman JA, Corona T, Delgado-Escueta A, Duron RM, et al. Calcific neurocysticercosis and epileptogenesis. Neurology 2004; 62: 1934–1938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Myint K, Mon S, Dhillon B, Singh G, Elangoven JK, Prasanth S. A rare ophthalmic presentation of neurocysticercosis. Neuro-Ophthalmology 2006; 30: 75–78. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nash TE, Singh G, White AC, Rajshekhar V, Loeb JA, Proano JV, et al. Treatment of neurocysticercosis: current status and future research needs. Neurology 2006; 67: 1120–1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rajshekhar V. Surgical management of neurocysticercosis. Int J Surg 2010; 8: 100–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sotelo J, Diaz-Olavarrieta C. Neurocysticercosis: changes after 25 years of medical therapy. Arch Med Res 2010; 41: 62–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]