Abstract

Practical relevance:

Bartonellae are small, vector-transmitted Gram-negative intracellular bacteria that are well adapted to one or more mammalian reservoir hosts. Cats are the natural reservoir for Bartonella henselae, which is a (re-)emerging bacterial pathogen. It can cause cat scratch disease in humans and, in immunocompromised people, may lead to severe systemic diseases, such as bacillary angiomatosis. Cats bacteraemic with B henselae constitute the main reservoir from which humans become infected. Most cats naturally infected with B henselae show no clinical signs themselves, but other Bartonella species for which cats are accidental hosts appear to have more pathogenicity.

Global importance:

Several studies have reported a prevalence of previous or current Bartonella species infection in cats of up to 36%. B henselae is common in cats worldwide, and bacteraemia can be documented by blood culture in about a quarter of healthy cats. The distribution of B henselae to various parts of the world has largely occurred through humans migrating with their pet cats. The pathogen is mainly transmitted from cat to cat by fleas, and the majority of infected cats derive from areas with high flea exposure. No significant difference in B henselae prevalence has been determined between male and female cats. In studies on both naturally and experimentally infected cats, chronic bacteraemia has mainly been found in cats under the age of 2 years, while those over 2 years of age are rarely chronically bacteraemic.

Evidence base:

This article reviews published studies and case reports on bartonellosis to explore the clinical significance of the infection in cats and its impact on humans. The article also discusses possible treatment options for cats and means of minimising the zoonotic potential.

Clinical signs in cats

It has often been suspected that Bartonella species may cause clinical signs in cats. Although several studies in experimentally and naturally infected cats have been undertaken to determine a cause–effect relationship between Bartonella species infections and clinical signs, a clear correlation has not been proven so far.

Bartonella henselae

Domestic cats are the natural reservoir for B henselae and are usually considered healthy carriers of this bacterium. However, some clinical signs have been connected to B henselae infection, based on studies involving naturally or experimentally infected cats. 1 Many studies rely on antibody detection,2–6 but are of limited value for establishing a correlation between infection and clinical signs because the presence of antibodies only demonstrates exposure and not necessarily active infection. Furthermore, because of the high prevalence of infection in healthy cats worldwide, it is not easy to demonstrate an association between clinical signs and the presence of B henselae.

Experimentally infected cats

Most cats experimentally infected by exposure to fleas do not develop clinical signs, 7 and it had been assumed that the mode of transmission would be important for clinical outcome. In a recent study, however, 3/6 cats experimentally infected by exposure to fleas showed lethargy and severe fever. One of these cats even developed myocarditis, pleural effusion, pericardial effusion, icterus and ataxia, and had to be euthanased. 8 In another study, 18 cats injected with B henselae-infected blood showed self-limiting febrile disease, transient mild anaemia, localised or generalised lymphadenopathy, mild neurological signs and reproductive failure. Necropsy revealed peripheral lymph node hyperplasia (in 13 cats), splenic follicular hyperplasia (nine cats), lymphocytic cholangitis/pericholangitis (nine cats), lymphocytic hepatitis (six cats), lymphoplasmacytic myocarditis (eight cats) and interstitial lymphocytic nephritis (four cats). 9 In a similar study, 12 cats received different numbers of colony-forming units (cfu)/ml (1010, 108 and 106, respectively) of B henselae intravenously. All cats became bacteraemic 2 weeks after inoculation. Cats infected with higher doses of B henselae developed lethargy, fever, partial anorexia and enlarged lymph nodes, but remained alert and responsive. Lymphoid hyperplasia was diagnosed on cytological evaluation of fine needle aspirates of the enlarged lymph nodes. 10

In most cases, therefore, persistent B henselae infection develops after experimental infection, but clinical signs, if present, are mild and cats recover without treatment.

Naturally infected cats

Most cats that are naturally infected with B henselae do not show clinical signs and appear to tolerate chronic bacteraemia without obvious clinical abnormalities. However, there have been several case reports and case- controlled studies that suggest a link between B henselae infection and a variety of clinical signs, as discussed below.

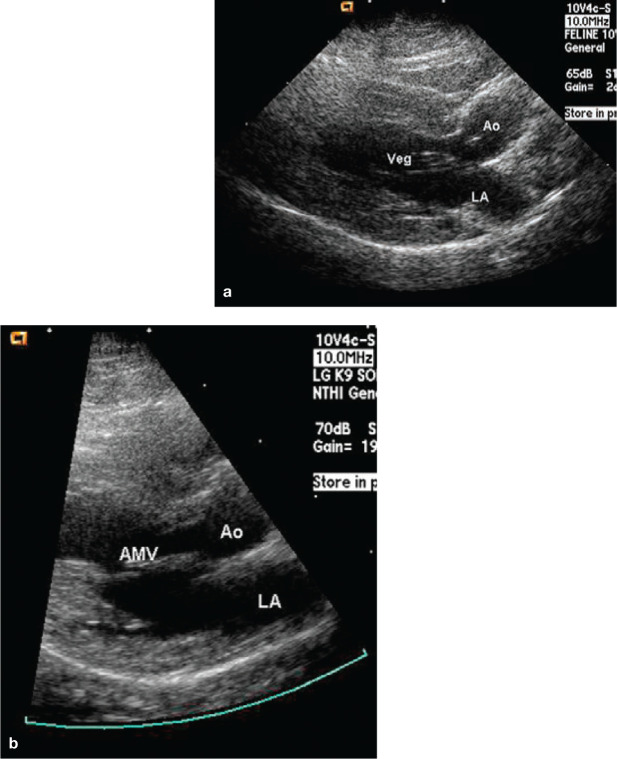

Endocarditis Although many Bartonella species have been associated with endocarditis in humans and dogs,11–13 endocarditis is rarely diagnosed in cats. In a case series in Australia, Bartonella species were isolated from the aortic valve of two cats with endocarditis, but direct causation was not proven. 14 In 2003, the first confirmed case of B henselae endocarditis in a cat was reported in the USA. Despite negative blood cultures, the cat had high Bartonella species antibody titres and B henselae DNA was detected in the damaged aortic valve. Microscopic examination of the valve after necropsy revealed endocarditis. 15 In 2009, a second confirmed case of endocarditis caused by B henselae in a cat was reported in the USA. A large hyperechoic vegetative lesion was identified by electrocardiography on the aortic valve, and B henselae DNA was detected in the damaged aortic valve. 16 In a recent case report from North Carolina, USA, B henselae was isolated from the blood of a cat diagnosed with mitral valve endocarditis (Figure 1). Following antibiotic therapy, the clinical signs, heart murmur and valvular lesion (as assessed by echocardiography) were shown to have resolved, and Bartonella species could not be isolated from a post-treatment blood culture. 17 Thus, there is sufficient evidence that infective endocarditis can be caused by natural B henselae infection in cats.

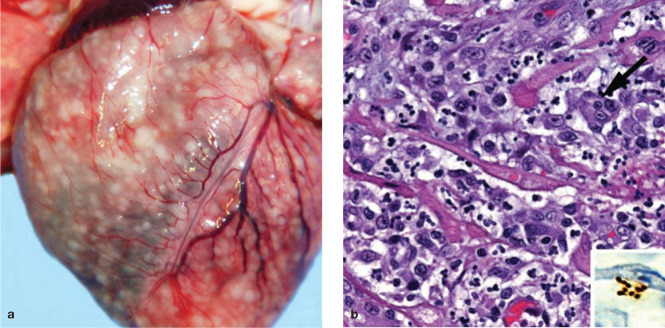

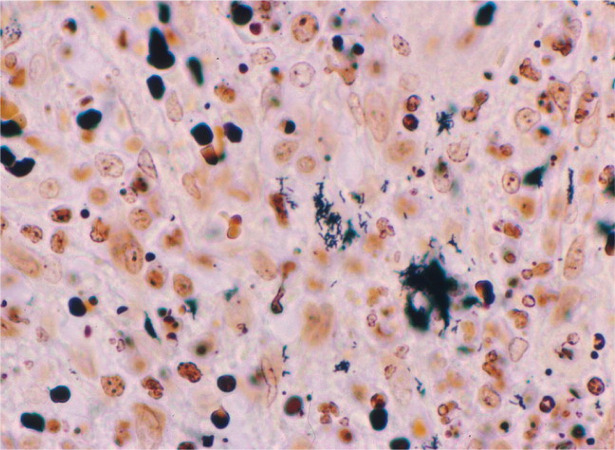

Myocarditis and diaphragmatic myositis Recently, pyogranulomatous myocarditis and diaphragmatic myositis was reported post mortem in two cats in the USA (Figure 2). 18 B henselae DNA was amplified and sequenced from the heart of one of these cats and from multiple tissue samples, including heart and diaphragm, from the second cat. This publication supports a potential association between B henselae and what has historically been described as ‘transmissible myocarditis and diaphragmitis’ of undetermined cause in cats.

CNS diseases A non-controlled retrospective study reported that antibodies to Bartonella species and Bartonella DNA can be found in the cerebrospinal fluid of cats with central nervous system (CNS) disease. 19 In that study, Bartonella species antibodies were detected in the serum of more cats with seizures than with other neurological manifestations. In another study, median B henselae antibody titres of cats with seizures were significantly higher than those of cats with other neurological diseases. 5 The results of these investigations suggest that Bartonella species infection may be associated with seizure disorders in cats. However, a clear causal relationship was not established and, furthermore, it has to be kept in mind that diagnosis of clinical bartonellosis cannot be based on antibody test results alone.5,9,20

Ocular diseases Some case reports and studies have suggested an association between B henselae infection and ocular disease. In one retrospective study, antibodies against all known Bartonella species were tested in serum samples of cats with ocular disease. This study found that Bartonella species can be a contributing factor for certain feline ocular diseases, such as uveitis or conjunctivitis. 21 In a naturally infected cat with anterior uveitis, intraocular B henselae antibody production was demonstrated after other potential causes of uveitis were excluded. 22 In one study, B henselae DNA was detected in the aqueous humour of two cats with uveitis and of experimentally infected cats without uveitis. However, only cats with uveitis had intraocular production of antibodies against B henselae, suggesting that B henselae may be a cause of feline uveitis.

Figure 1.

Endocarditis in a 3-year-old male castrated cat with B henselae infection. (a) Left parasternal long-axis view showing an echogenic vegetative lesion (Veg) associated with the anterior mitral leaflet and which was noted to move independently of the leaflet. LA = left atrium, Ao = aorta. (b) Image obtained 3 weeks after completing a 6-week course of antibiotic therapy. The vegetative mitral valve lesion is no longer present. Reproduced, with permission, from Perez et al (2010) 17

Figure 2.

Gross and histological findings in two cats from a North Carolina shelter that died after a litter of flea-infested kittens was introduced to the shelter. (a) Coalescing granulomas distributed throughout the myocardium of an approximately 9-week-old female kitten. (b) Pyogranulomatous myocarditis in an 8-month-old castrated male cat, which had been co-housed with the flea-infested kittens. Macrophages, with a rare multinucleated giant cell (arrow), are particularly numerous towards the upper left of the image; haematoxylin and eosin stain. Inset: Cluster of short bacilli in an inflammatory focus are immunoreactive (brown) for B henselae-specific monoclonal antibody; immunohistochemistry with diaminobenzidine chromogen and haematoxylin counterstain. Reproduced, with permission, from Varanat et al (2012) 18

In another study, antibody titres in serum and aqueous humour and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) results from aqueous humour samples from 49 client-owned cats with uveitis, 49 healthy shelter cats and nine cats experimentally inoculated with either B henselae or B clarridgeiae were examined. Ocular production of Bartonella species IgG was detected in 7/49 cats with uveitis, 0/49 healthy shelter cats and 4/9 experimentally inoculated cats. The organism was detected by PCR in the aqueous humour of 3/24 cats with uveitis, 1/49 healthy shelter cats and 4/9 experimentally inoculated cats. The authors concluded that Bartonella species may infect the eyes of some cats following natural exposure or experimental inoculation and may be a cause of uveitis. 23 However, in another study that compared 113 cats with uveitis with 253 cats that were healthy or had non-ocular disease, there was no difference in serum antibody prevalence or titre magnitude between the groups. 24 The median B henselae titre was 1:64 for all cats, and healthy cats were even more likely to have higher titres than cats with uveitis or cats with non-ocular disease. 24 Despite the case report in which B henselae was strongly suspected as a cause of uveitis, 22 there is only weak evidence to substantiate B henselae as being a common cause of uveitis in cats.

Stomatitis Some early studies suggested that B henselae may play a role in the pathophysiology of chronic stomatitis in cats.3,6 However, more recent work demonstrated that the prevalence of antibodies, bacteraemia or tissue infection was not higher in cats with chronic gingivostomatitis than in control populations.25–29 Belgard et al found no significant difference in the prevalence of B henselae DNA (blood samples and oropharyngeal swabs) or antibodies between cats with chronic stomatitis and control cats. 25 The results of these studies suggest that B henselae does not play a role in chronic stomatitis in cats.

Rhinosinusitis A study investigating the association between natural B henselae infection and chronic rhinosinusitis did not reveal significant differences in antibody prevalence or culture results for B henselae in cats with chronic rhinosinusitis compared with control cats. 30 Nasal tissue specimens were all negative by PCR. This suggests that B henselae likewise does not play an important role in the pathogenesis of chronic rhinosinusitis.

Immune complex diseases B henselae may be an important pathogen as far as immune complex dieases in cats are concerned. A very recent study investigated the association between B henselae infection and hyperglobulinaemia in cats. Serum protein electrophoresis was performed on samples from 50 cats with and without antibodies to B henselae. For every 1 mg/dl increase in globulin concentration, the likelihood of having a B henselae antibody titre increased 4.37-fold. These results demonstrate a strong correlation between the presence of antibodies against Bartonella species and hyperglobulinaemia. 31

Other Bartonella species

As a rule, Bartonella species rarely cause clinical signs in their reservoir host, but may cause disease in an accidental host. 32 As well as being the reservoir host for B henselae, cats can also be infected with B clarridgeiae, B koehlerae, B quintana, B vinsonii subspecies berkhoffii and B bovis (formerly B weissii).1,33

The role of B clarridgeiae in cats has not been clarified. Cats can be infected with this Bartonella species without clinical signs and transmit it to humans and, thus, may serve as reservoir host. B clarridgeiae has also been implicated as an agent of cat scratch disease (CSD) in humans and aortic valve endocarditis and hepatic disease in dogs. 34 In a study in Alabama and Florida, USA, not only B henselae DNA, but also B clarridgeiae DNA was isolated from blood, skin biopsies, gingival swabs and claw bed swabs of feral cats. 35 In a separate study in the USA, DNA of B clarridgeiae was amplified from the blood of cats or the fleas taken from those cats, and concurrent infection of cats and their fleas with both Bartonella organisms was common. 36 In an investigation into the association between B clarridgeiae infection and chronic rhinosinusitis in cats, no differences in antibody positivity or culture results were found in cats with chronic rhinosinusitis compared with healthy cats. 30 It is unclear whether cats are the main reservoir host for B clarridgeiae or are accidental hosts. It is also unclear how often cats develop clinical signs after B clarridgeiae infection.

B quintana DNA has been amplified from cat fleas 37 and ticks, 38 and the organism has been isolated from feral cats. These cats were healthy, but the pathogenicity of B quintana in cats is unknown, as is the potential for cats to transmit B quintana to humans. 39

Isolation of B koehlerae from the blood of domestic cats has been documented in two cases. In the first report, from the USA, two B koehlerae isolates were recovered from two kittens living in the same household. 40 The second report was from France, where B koehlerae was detected in the blood of a kitten suspected of causing CSD in its owner. 41 In addition, B koehlerae has been isolated from stray cats in Israel. 42

B bovis has been isolated from a few cats in the USA. The genome of the cat isolate was 80% identical to isolates found in more than 35% of 36 French dairy cattle. It was postulated that the cat isolate may have resulted from a transfer of B bovis from a bovine to a feline population some time ago. 43 It is unknown if B bovis may cause clinical signs in cats and/or whether cats may transmit the bacterium to cattle or to humans.

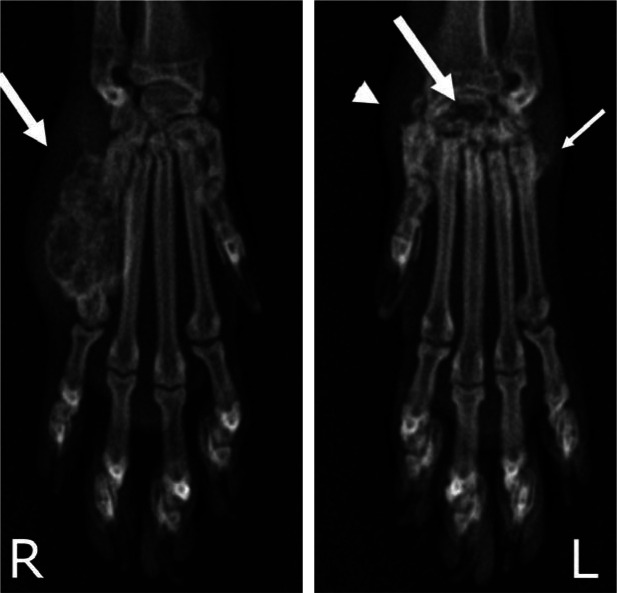

B vinsonii subspecies berkhoffii, the Bartonella species most commonly found in dogs, was detected by blood culture in a cat affected by recurrent osteomyelitis and polyarthritis, lameness, swollen limbs and limb pain (Figure 3). The cat was found to be hypercalcaemic, hyperglobulinaemic and thrombocytopenic. After treatment with antibiotics for 3 months, the cat was walking without pain, and blood culture was negative. Thus, Bartonella species infection may be considered in the differential diagnosis of feline osteomyelitis. 44

Figure 3.

Dorsopalmar radiographs of the front feet of a 5-year-old spayed female cat with polyarthritis and osteomyelitis associated with B vinsonii subspecies berkhoffii infection. Note the aggressive expansile lesion of the fifth metacarpal bone and adjacent soft tissue swelling (arrow) in the right foot, and the severe osteolysis of the radial carpal bone (large arrow), osteoproliferation of the carpal and metacarpal bones (small arrow), and carpal joint effusion (arrowhead) in the left foot. Reproduced, with permission, from Varanat et al (2009) 44

Clinical signs in humans

The genus Bartonella comprises several important human pathogens that are associated with a wide range of clinical manifestations. These include long-recognised diseases such as Carrion’s disease, caused by B bacilliformis, and trench fever, caused by B quintana. CSD, as discussed, can be caused by B henselae and B clarridgeiae.45–47 Bacillary angiomatosis and peliosis hepatitis have been described due to B henselae and B quintana infection. Chronic lymphadenopathy has been associated with B quintana. In humans with endocarditis, B henselae, B quintana and B elizabethae have been identified.47–49

B henselae is the most common pathogen transmitted from cats to humans and is considered a zoonotic agent. In various studies performed in the early and mid-1990s, the prevalence of antibodies to B henselae in humans ranged from 4–6%.50–52 In a more recent (2003) study, 23% of examined people had antibodies against B henselae. However, no difference was seen between people with and without domestic pets; nor were differences noted in terms of age, sex, urban or rural residence, or concomitant diseases. 53

While the route of transmission from cat to cat, though not unequivocally clear, is thought to happen indirectly via flea transfer from one cat to another, 8 the transmission of B henselae from cats to humans can occur directly, usually via scratches and bites, or indirectly, by means of the cat flea (Ctenocephalides felis). Most commonly, transmission occurs via the following route:

Cat scratches and bites have been shown to be significantly associated with the development of CSD,51,54 which appears to be the most common clinical presentation of B henselae infection in humans (Figure 4) and has been reported worldwide. In the United States, epidemiological databases estimate that approximately 24,000 cases of CSD occur annually, with a calculated incidence of 9.3/10,000 ambulatory patients per year. 53

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemical identification of B henselae in a case of cat scratch disease. With Warthin-Starry silver stain, these coccobacillary pathogens can be seen singly, in small clumps or in chains in necrotic foci. Courtesy of Dharam Ramnani, Webpathology.com

CSD is a persistent, necrotising inflammation of the lymph nodes. Its typical form is characterised by self-limiting regional lymphadenopathy that follows the development of a primary papular lesion and lasts from a few weeks to months. 1 Abscessation of the lymph node and systemic signs (such as fever) are occasionally reported. Atypical forms of CSD are also described; for example, encephalopathies in children and other neurological abnormalities. An unusual case of CSD has recently been reported in a veterinarian affected by persistent fever and back pain after an accidental needle puncture. 55

The immune status of a person infected with B henselae plays an important role in the outcome. In most immunocompetent people, B henselae infection has no clinical sequelae. 56 However, in some immunocompetent people, B henselae causes the typical form of CSD,57,58 which is seen most commonly in children (it is rarely seen in adults). 56 Immunocompromised people may develop atypical CSD and more severe forms of Bartonella-associated disease, which may be fatal if left untreated. These include bacillary angiomatosis, 59 parenchymal bacillary peliosis, relapsing fever with bacteraemia, 60 endocarditis,61–63 neuroretinitis, 64 aseptic meningitis 65 and uveitis. 66

What to do with a Bartonella-infected cat

Current therapeutic strategies in cats are based on in vitro studies, experience gained with human bartonellosis and case reports. Data from controlled efficacy studies in cats are lacking. While many antibiotics are effective in vitro, in vivo efficacy is limited. Elimination of Bartonella species is usually not achieved by treatment, though bacterial load decreases and clinical signs resolve. 68

Several drugs (doxycycline, amoxicillin, amoxicillin–clavulanic acid, enrofloxacin, erythromycin, rifampicin) have been used in cats naturally or experimentally infected with Bartonella species.69–71 Complete clearance of Bartonella species has not been seen with any of the drugs used.

Infected cats without clinical signs

Older cats (ie, over 2 years of age) are able to eliminate Bartonella species without antimicrobial therapy and develop an age-related resistance. In the light of this and the very rare occurrence of disease in cats, and despite the zoonotic risk, symptomless cats infected with B henselae should only be treated in particular circumstances. If young infected cats (under 2 years of age) live in a household with immunocompromised people or with children, they should be treated, regardless of whether or not they show clinical signs. In this scenario, treatment is aimed at decreasing bacterial load and thus the risk of transmission.

The treatment of choice in healthy infected cats living with immunocompromised people is doxycycline (5–10 mg/kg PO q12–24h). Treatment does not lead to total elimination of Bartonella species in all cats; in many cases it serves only to decrease the bacterial load. In one study, bacteraemia was only eliminated in 1/6 cats treated for 14 days and 1/2 cats treated for 28 days. 72

Healthy infected cats that do not live in a household with immunocompromised people or with children should not be treated with antibiotics.

Infected cats with clinical signs

Treatment is also recommended in the rare instances when Bartonella species actually cause disease in a cat. One study tested the in vitro efficacy of 17 antimicrobial compounds. Telithromycin, macrolides, doxycycline and rifampicin were found to be the most effective agents against Bartonella species. 73 There are several case reports documenting use of drugs in affected cats with some success. A cat with recurrent osteomyelitis and polyarthritis associated with B vinsonii subspecies berkhoffii infection and bacteraemia (see Figure 3) recovered after therapy with azithromycin (10 mg/kg PO q48h for 3 months) and amoxicillin–clavulanic acid (62.5 mg PO q12h for 2 months). 44 A cat with B henselae endocarditis was successfully treated with a combination of marbofloxacin (5 mg/kg PO q24h) and azithromycin (10 mg/kg PO q24h for 7 days and then q48h) for 6 weeks. 17

Figure 5.

Fleas and ‘flea dirt’ represent the greatest risk factor. Courtesy of Dr Michael R Lappin and HESKA Corporation

Footnotes

Funding: The authors received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors for the preparation of this review.

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Key Points

Infections with Bartonella species are of global importance.

Cats are the reservoir host for B henselae, which causes cat scratch disease and other clinical diseases in humans.

Most cats naturally infected with B henselae do not show clinical signs and appear to tolerate chronic bacteraemia without obvious clinical abnormalities.

In occasional cats, B henselae infections have caused clinical disease such as endocarditis and uveitis. A causal relationship with other conditions, such as CNS disease, rhinotracheitis and stomatitis, has not been proven.

Bartonella species other than B henselae can cause more severe disease in cats.

The immune status of a person infected with Bartonella species plays an important role in the outcome. Most immunocompetent people will have no clinical signs, while immunocompromised people may develop severe Bartonella-associated disease.

Only infected cats younger than 2 years living with immunocompromised owners or with children, or cats that have Bartonella-associated disease, should be treated with antibiotics.

References

- 1. Boulouis HJ, Chang CC, Henn JB, Kasten RW, Chomel BB. Factors associated with the rapid emergence of zoonotic Bartonella infections. Vet Res 2005; 36: 383–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bayliss DB, Steiner JM, Sucholdolski JS, Radecki SV, Brewer MM, Morris AK, et al. Serum feline pancreatic lipase immunoreactivity concentration and seroprevalences of antibodies against Toxoplasma gondii and Bartonella species in client-owned cats. J Feline Med Surg 2009; 11: 663–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Glaus T, Hofmann-Lehmann R, Greene C, Glaus B, Wolfensberger C, Lutz H. Seroprevalence of Bartonella henselae infection and correlation with disease status in cats in Switzerland. J Clin Microbiol 1997; 35: 2883–2885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ishak AM, Radecki S, Lappin MR. Prevalence of Mycoplasma haemofelis, ‘Candidatus Mycoplasma haemominutum’, Bartonella species, Ehrlichia species, and Anaplasma phagocytophilum DNA in the blood of cats with anemia. J Feline Med Surg 2007; 9: 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pearce LK, Radecki SV, Brewer M, Lappin MR. Prevalence of Bartonella henselae antibodies in serum of cats with and without clinical signs of central nervous system disease. J Feline Med Surg 2006; 8: 315–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ueno H, Hohdatsu T, Muramatsu Y, Koyama H, Morita C. Does coinfection of Bartonella henselae and FIV induce clinical disorders in cats? Microbiol Immunol 1996; 40: 617–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chomel BB, Kasten RW, Floyd-Hawkins K, Chi B, Yamamoto K, Roberts-Wilson J, et al. Experimental transmission of Bartonella henselae by the cat flea. J Clin Microbiol 1996; 34: 1952–1956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bradbury CA, Lappin MR. Evaluation of topical application of 10% imidacloprid– 1% moxidectin to prevent Bartonella henselae transmission from cat fleas. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2010; 236: 869–873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kordick DL, Brown TT, Shin K, Breitschwerdt EB. Clinical and pathologic evaluation of chronic Bartonella henselae or Bartonella clarridgeiae infection in cats. J Clin Microbiol 1999; 37: 1536–1547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Guptill L, Slater L, Wu CC, Lin TL, Glickman LT, Welch DF, et al. Experimental infection of young specific pathogen-free cats with Bartonella henselae. J Infect Dis 1997; 176: 206–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Breitschwerdt EB, Hegarty BC, Davidson MG, Szabados NS. Evaluation of the pathogenic potential of Rickettsia canada and Rickettsia prowazekii organisms in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1995; 207: 58–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. La Scola B, Raoult D. Culture of Bartonella quintana and Bartonella henselae from human samples: a 5-year experience (1993 to 1998). J Clin Microbiol 1999; 37: 1899–1905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. MacDonald KA, Chomel BB, Kittleson MD, Kasten RW, Thomas WP, Pesavento P. A prospective study of canine infective endocarditis in northern California (1999–2001): emergence of Bartonella as a prevalent etiologic agent. J Vet Intern Med 2004; 18: 56–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Malik R, Barrs VR, Church DB, Zahn A, Allan GS, Martin P, et al. Vegetative endocarditis in six cats. J Feline Med Surg 1999; 1: 171–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chomel BB, Wey AC, Kasten RW, Stacy BA, Labelle P. Fatal case of endocarditis associated with Bartonella henselae type I infection in a domestic cat. J Clin Microbiol 2003; 41: 5337–5339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chomel BB, Kasten RW, Williams C, Wey AC, Henn JB, Maggi R, et al. Bartonella endocarditis: a pathology shared by animal reservoirs and patients. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2009; 1166: 120–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Perez C, Hummel JB, Keene BW, Maggi RG, Diniz PP, Breitschwerdt EB. Successful treatment of Bartonella henselae endocarditis in a cat. J Feline Med Surg 2010; 12: 483–486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Varanat M, Broadhurst J, Linder KE, Maggi RG, Breitschwerdt EB. Identification of Bartonella henselae in two cats with pyogranulomatous myocarditis and diaphragmatic myositis. Vet Pathol 2012; 49: 608–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Leibovitz K, Pearce L, Brewer M, Lappin MR. Bartonella species antibodies and DNA in cerebral spinal fluid of cats with central nervous system disease. J Feline Med Surg 2008; 10: 332–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Guptill L, Wu CC, HogenEsch H, Slater LN, Glickman N, Dunham A, et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and genetic diversity of Bartonella henselae infections in pet cats in four regions of the United States. J Clin Microbiol 2004; 42: 652–659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ketring KL, Zuckerman EE, Hardy WD., Jr. Bartonella: a new etiological agent of feline ocular disease. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2004; 40: 6–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lappin MR, Black JC. Bartonella spp infection as a possible cause of uveitis in a cat. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1999; 214: 1205–1207, 1200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lappin MR, Kordick DL, Breitschwerdt EB. Bartonella spp antibodies and DNA in aqueous humour of cats. J Feline Med Surg 2000; 2: 61–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fontenelle JP, Powell CC, Hill AE, Radecki SV, Lappin MR. Prevalence of serum antibodies against Bartonella species in the serum of cats with or without uveitis. J Feline Med Surg 2008; 10: 41–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Belgard S, Truyen U, Thibault JC, Sauter-Louis C, Hartmann K. Relevance of feline calicivirus, feline immunodeficiency virus, feline leukemia virus, feline herpesvirus and Bartonella henselae in cats with chronic gingivostomatitis. Berl Munch Tierarztl Wochenschr 2010; 123: 369–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dowers KL, Hawley JR, Brewer MM, Morris AK, Radecki SV, Lappin MR. Association of Bartonella species, feline calicivirus, and feline herpesvirus 1 infection with gingivostomatitis in cats. J Feline Med Surg 2010; 12: 314–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Namekata DY, Kasten RW, Boman DA, Straub MH, Siperstein-Cook L, Couvelaire K, et al. Oral shedding of Bartonella in cats: correlation with bacteremia and seropositivity. Vet Microbiol 2010; 146: 371–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pennisi MG, La Camera E, Giacobbe L, Orlandella BM, Lentini V, Zummo S, et al. Molecular detection of Bartonella henselae and Bartonella clarridgeiae in clinical samples of pet cats from Southern Italy. Res Vet Sci 2010; 88: 379–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Quimby JM, Elston T, Hawley J, Brewer M, Miller A, Lappin MR. Evaluation of the association of Bartonella species, feline herpesvirus 1, feline calicivirus, feline leukemia virus and feline immunodeficiency virus with chronic feline gingivostomatitis. J Feline Med Surg 2008; 10: 66–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Berryessa NA, Johnson LR, Kasten RW, Chomel BB. Microbial culture of blood samples and serologic testing for bartonellosis in cats with chronic rhinosinusitis. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2008; 233: 1084–1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Whittemore JC, Hawley JR, Radecki SV, Steinberg JD, Lappin MR. Bartonella species antibodies and hyperglobulinemia in privately owned cats. J Vet Intern Med 2012; 26: 639–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Breitschwerdt EB, Maggi RG, Chomel BB, Lappin MR. Bartonellosis: an emerging infectious disease of zoonotic importance to animals and human beings. J Vet Emerg Crit Care (San Antonio) 2010; 20: 8–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chomel BB, Boulouis HJ, Maruyama S, Breitschwerdt EB. Bartonella spp in pets and effect on human health. Emerg Infect Dis 2006; 12: 389–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gillespie TN, Washabau RJ, Goldschmidt MH, Cullen JM, Rogala AR, Breitschwerdt EB. Detection of Bartonella henselae and Bartonella clarridgeiae DNA in hepatic specimens from two dogs with hepatic disease. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2003; 222: 47–51, 35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lappin MR, Hawley J. Presence of Bartonella species and Rickettsia species DNA in the blood, oral cavity, skin and claw beds of cats in the United States. Vet Dermatol 2009; 20: 509–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lappin MR, Griffin B, Brunt J, Riley A, Burney D, Hawley J, et al. Prevalence of Bartonella species, haemoplasma species, Ehrlichia species, Anaplasma phagocytophilum, and Neorickettsia risticii DNA in the blood of cats and their fleas in the United States. J Feline Med Surg 2006; 8: 85–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rolain JM, Franc M, Davoust B, Raoult D. Molecular detection of Bartonella quintana, B koehlerae, B henselae, B clarridgeiae, Rickettsia felis, and Wolbachia pipientis in cat fleas, France. Emerg Infect Dis 2003; 9: 338–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chang CC, Chomel BB, Kasten RW, Romano V, Tietze N. Molecular evidence of Bartonella spp in questing adult Ixodes pacificus ticks in California. J Clin Microbiol 2001; 39: 1221–1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Breitschwerdt EB, Maggi RG, Sigmon B, Nicholson WL. Isolation of Bartonella quintana from a woman and a cat following putative bite transmission. J Clin Microbiol 2007; 45: 270–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Droz S, Chi B, Horn E, Steigerwalt AG, Whitney AM, Brenner DJ. Bartonella koehlerae sp nov, isolated from cats. J Clin Microbiol 1999; 37: 1117–1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rolain JM, Fournier PE, Raoult D, Bonerandi JJ. First isolation and detection by immunofluorescence assay of Bartonella koehlerae in erythrocytes from a French cat. J Clin Microbiol 2003; 41: 4001–4002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Avidor B, Graidy M, Efrat G, Leibowitz C, Shapira G, Schattner A, et al. Bartonella koehlerae, a new cat-associated agent of culture-negative human endocarditis. J Clin Microbiol 2004; 42: 3462–3468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bermond D, Boulouis HJ, Heller R, Van Laere G, Monteil H, Chomel BB, et al. Bartonella bovis sp nov and Bartonella capreoli sp nov, isolated from European ruminants. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2002; 52: 383–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Varanat M, Travis A, Lee W, Maggi RG, Bissett SA, Linder KE, et al. Recurrent osteomyelitis in a cat due to infection with Bartonella vinsonii subsp berkhoffii genotype II. J Vet Intern Med 2009; 23: 1273–1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Jerris RC, Regnery RL. Will the real agent of cat-scratch disease please stand up? Annu Rev Microbiol 1996; 50: 707–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kordick DL, Hilyard EJ, Hadfield TL, Wilson KH, Steigerwalt AG, Brenner DJ, et al. Bartonella clarridgeiae, a newly recognized zoonotic pathogen causing inoculation papules, fever, and lymphadenopathy (cat scratch disease). J Clin Microbiol 1997; 35: 1813–1838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Maurin M, Birtles R, Raoult D. Current knowledge of Bartonella species. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 1997; 16: 487–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Anderson B, Sims K, Regnery R, Robinson L, Schmidt MJ, Goral S, et al. Detection of Rochalimaea henselae DNA in specimens from cat scratch disease patients by PCR. J Clin Microbiol 1994; 32: 942–948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Maurin M, Raoult D. Bartonella (Rochalimaea) quintana infections. Clin Microbiol Rev 1996; 9: 273–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Jackson LA, Perkins BA, Wenger JD. Cat scratch disease in the United States: an analysis of three national databases. Am J Public Health 1993; 83: 1707–1711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Zangwill KM, Hamilton DH, Perkins BA, Regnery RL, Plikaytis BD, Hadler JL, et al. Cat scratch disease in Connecticut. Epidemiology, risk factors, and evaluation of a new diagnostic test. N Engl J Med 1993; 329: 8–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hamilton DH, Zangwill KM, Hadler JL, Cartter ML. Cat-scratch disease – Connecticut, 1992–1993. J Infect Dis 1995; 172: 570–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Skerget M, Wenisch C, Daxboeck F, Krause R, Haberl R, Stuenzner D. Cat or dog ownership and seroprevalence of ehrlichiosis, Q fever, and cat-scratch disease. Emerg Infect Dis 2003; 9: 1337–1340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Tappero JW, Mohle-Boetani J, Koehler JE, Swaminathan B, Berger TG, LeBoit PE, et al. The epidemiology of bacillary angiomatosis and bacillary peliosis. JAMA 1993; 269: 770–775. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lin JW, Chen CM, Chang CC. Unknown fever and back pain caused by Bartonella henselae in a veterinarian after a needle puncture: a case report and literature review. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2011; 11: 589–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Massei F, Messina F, Gori L, Macchia P, Maggiore G. High prevalence of antibodies to Bartonella henselae among Italian children without evidence of cat scratch disease. Clin Infect Dis 2004; 38: 145–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Dolan MJ, Wong MT, Regnery RL, Jorgensen JH, Garcia M, Peters J, et al. Syndrome of Rochalimaea henselae adenitis suggesting cat scratch disease. Ann Intern Med 1993; 118: 331–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Regnery RL, Olson JG, Perkins BA, Bibb W. Serological response to Rochalimaea henselae antigen in suspected cat-scratch disease. Lancet 1992; 339: 1443–1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Relman DA, Loutit JS, Schmidt TM, Falkow S, Tompkins LS. The agent of bacillary angiomatosis. An approach to the identification of uncultured pathogens. N Engl J Med 1990; 323: 1573–1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Slater LN, Welch DF, Hensel D, Coody DW. A newly recognized fastidious Gram-negative pathogen as a cause of fever and bacteremia. N Engl J Med 1990; 323: 1587–1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. De La, Rosa GR, Barnett BJ, Ericsson CD, Turk JB. Native valve endocarditis due to Bartonella henselae in a middle-aged human immunodeficiency virus-negative woman. J Clin Microbiol 2001; 39: 3417–3419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Fournier PE, Lelievre H, Eykyn SJ, Mainardi JL, Marrie TJ, Bruneel F, et al. Epidemiologic and clinical characteristics of Bartonella quintana and Bartonella henselae endocarditis: a study of 48 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2001; 80: 245–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Tsuneoka H, Yanagihara M, Otani S, Katayama Y, Fujinami H, Nagafuji H, et al. A first Japanese case of Bartonella henselae-induced endocarditis diagnosed by prolonged culture of a specimen from the excised valve. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2010; 68: 174–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Kodama T, Masuda H, Ohira A. Neuroretinitis associated with cat-scratch disease in Japanese patients. Acta Ophthalmol Scand 2003; 81: 653–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Wong MT, Dolan MJ, Lattuada CP, Jr, Regnery RL, Garcia ML, Mokulis EC, et al. Neuroretinitis, aseptic meningitis, and lymphadenitis associated with Bartonella (Rochalimaea) henselae infection in immunocompetent patients and patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Clin Infect Dis 1995; 21: 352–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Font RL, Del Valle M, Mitchell BM, Boniuk M. Cat-scratch uveitis confirmed by histological, serological, and molecular diagnoses. Cornea 2011; 30: 468–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Kaplan JE, Benson C, Holmes KH, Brooks JT, Pau A, Masur H. Guidelines for prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in HIV-infected adults and adolescents: recommendations from CDC, the National Institutes of Health, and the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. MMWR Recomm Rep 2009; 58: 1–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Kordick DL, Papich MG, Breitschwerdt EB. Efficacy of enrofloxacin or doxycycline for treatment of Bartonella henselae or Bartonella clarridgeiae infection in cats. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1997; 41: 2448–2455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Greene CE, McDermott M, Jameson PH, Atkins CL, Marks AM. Bartonella henselae infection in cats: evaluation during primary infection, treatment, and rechallenge infection. J Clin Microbiol 1996; 34: 1682–1685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Regnery RL, Rooney JA, Johnson AM, Nesby SL, Manzewitsch P, Beaver K, et al. Experimentally induced Bartonella henselae infections followed by challenge exposure and antimicrobial therapy in cats. Am J Vet Res 1996; 57: 1714–1719. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Kordick DL, Breitschwerdt EB. Relapsing bacteremia after blood transmission of Bartonella henselae to cats. Am J Vet Res 1997; 58: 492–497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Hartmann K, Hein J. Bartonellose. In: Infektionskrankheiten der katze. Hannover: Schlütersche Verlagsgesellschaft mbH & Co KG, 2008, pp 182–188. [Google Scholar]

- 73. Dorbecker C, Sander A, Oberle K, Schulin-Casonato T. In vitro susceptibility of Bartonella species to 17 antimicrobial compounds: comparison of Etest and agar dilution. J Antimicrob Chemother 2006; 58: 784–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Foley JE, Chomel B, Kikuchi Y, Yamamoto K, Pedersen NC. Seroprevalence of Bartonella henselae in cattery cats: association with cattery hygiene and flea infestation. Vet Q 1998; 20: 1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Brunt J, Guptill L, Kordick DL, Kudrak S, Lappin MR. American Association of Feline Practitioners 2006 Panel report on diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of Bartonella spp. infections. J Feline Med Surg 2006; 8: 213–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Brown RR, Elston TH, Evans L, Glaser C, Gulledge ML, Jarboe L, et al. Feline zoonosis guidelines from the American Association of Feline Practitioners. J Feline Med Surg 2005; 7: 243–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]