Abstract

Intussusception associated with lymphoma of the ileocaecocolic junction was diagnosed in a 12-year-old female domestic short-haired cat that presented with a 3-week history of diarrhoea and a protruding anal mass. Surgical exploration revealed an ileocolonic intussusception proximal to the mass at the ileocaecal junction which was excised. A diagnosis of ileocaecocolic lymphosarcoma was made and euthanasia was later performed. This is an unusual case of an ileocaecal junction tumour that manifested as a rectal prolapse associated with intussusception in a cat.

Intussusceptions are most often reported in dogs. When they do occur in cats, the majority of cases present in young animals and frequently no predisposing factors can be identified. The most prevalent location of intussusceptions is the ileocolic region (Wilson & Burt 1974, Weaver 1977). It has been postulated that a change in diameter at this site may be responsible, resulting in a kink in the bowel wall that can act as a stimulus to the development of an intussusception (Lewis & Ellison 1987). This case report describes a prolapse of an ileocaecal junction tumour through the anus in a cat associated with an intussusception.

A 12-year-old female neutered domestic short-haired cat presented as an emergency to The University of Edinburgh Hospital for Small Animals with a mass protruding from the anus.

The cat was fully vaccinated against feline herpesvirus, calicivirus, panleucopenia and leukaemia virus. For the 3 weeks prior to presentation the cat had been unsuccessfully treated for intermittent diarrhoea with dietary manipulation and anthelmintics. The mass had only appeared that evening and the cat had been licking at it constantly.

The cat was agitated on presentation. Clinical examination revealed a grade II/VI systolic heart murmur on the left side of the thorax with a normal heart rate (180 beats per min) and no pulse deficits. Rectal temperature was 101.0°F. Abdominal palpation revealed moderately thickened small intestines. The protrusion from the anus was a regular, smooth round mass measuring approximately 3 × 3 cm. The surface was moist and dark red in colour with a small amount of haemorrhage. Differentials included a prolapsed neoplasm, a prolapsed intussusception or prolapsed rectum. At this stage the mass was manually reduced after copious lavage with 0.9% sterile saline and application of a lubricating water based gel (K-Y Lubricating Jelly; Johnson & Johnson). A digital rectal examination afterwards could not localise the mass and palpation of the rectal wall was unremarkable. An injection of amoxycillin/clavulanate (Synulox; Pfizer) was administered.

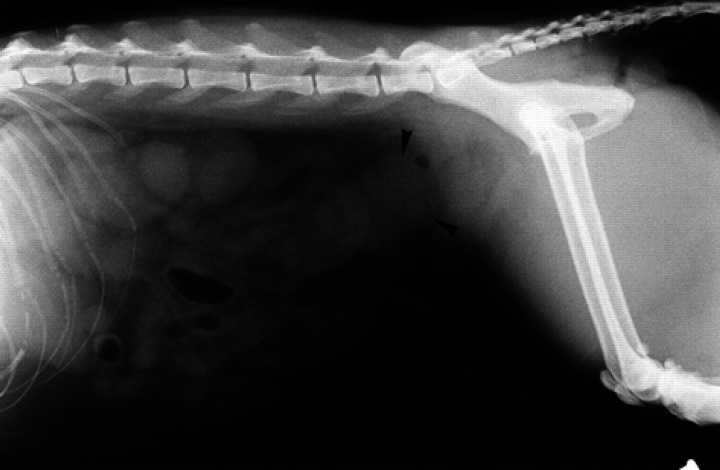

Twenty-four hours later the mass was not evident externally. Haematology and serum biochemical abnormalities included neutrophilia 13.7 × 109/l (normal range 2.5–12.8), hypoalbuminaemia 23.3 g/l (28–39) and T4 <5 nmol/l (13–48). A rectal examination was carried out under general anaesthesia which was unremarkable. Abdominal palpation revealed the presence of a large round and regular mass about 3 cm in diameter associated with the intestinal tract in the caudal portion of the abdomen. The mass was mobile and could be drawn further caudally into the pelvis so that it was just palpable per rectum. A lateral abdominal radiograph of the abdomen revealed a large soft tissue density in the region of the caudal abdomen, which in view of the clinical findings was likely to be the mass (Fig 1). No abnormalities were detected on thoracic radiography. Colonoscopy, using a 9 mm diameter fibre-optic flexible endoscope, showed the presence of a large smooth mass located approximately 10 cm proximal to the anus (Fig 2). At the distal end of the mass the colonic lumen was still patent. However, within 2 cm proximal to the distal margins of the mass the entire lumen of the colon was obliterated rendering the passage of the endoscope impossible. The wall of the colon distal to the mass was abnormally congested. Multiple biopsies were taken of the mass itself and of the colonic wall which was found to be friable. After ensuring minor haemorrhage had stopped, the cat was recovered from anaesthesia. The histopathology of all samples reported non-specific chronic inflammatory changes with at least half of the samples consisting of superficial debris which may have been masking underlying disease. No discernible neoplastic tissue was identified. During the investigative procedures the cat remained reasonably bright, ate a little and produced only a single small amount of dry faeces.

Fig 1.

Lateral radiograph of the abdomen showing a soft tissue density (black arrows) in the caudal abdomen where the mass was palpable. Note the lack of faeces in the colon.

Fig 2.

The view of the mass with the endoscope. The mass obliterates the entire lumen of the colon and appears to be bulging towards the camera.

The following day the mass had re-prolapsed from the anus. Impression smears and fine needle aspirates were taken but were non-diagnostic. The cat was premedicated with acetylpromazine (0.03 mg/kg) and morphine (0.25 mg/kg) given intramuscularly. Anaesthesia was induced by intravenous injection of propofol (Rapinovet; Shering-Plough Animal Health) at 4 mg/kg and maintained by isoflurane delivered in oxygen via a non-rebreathing circuit. Cephazolin (Kefzol; Lilly) at 20 mg/kg was administered intravenously and metronidazole (Torgyl solution; Rhone Merieux) at 10 mg/kg was given over 12 h as a continuous infusion with compound sodium lactate solution. A full abdominal exploration revealed a generalised thickening of the small intestines. At the ileocaecal junction, an intussusception was evident with most of the ileum forming the apex of the intussusception and the ileocaecal junction forming the neck. The intussusception was reducible but the ileocaecal junction was enlarged, thickened and fibrotic with an obvious mass attached to it. The associated mesenteric lymph nodes were grossly normal. Once reduced, the ileum appeared to be viable but an enterectomy was performed to remove the mass at the ileocaecal junction. Approximately 2 cm of ileum proximal to the ileocaecal junction and 2 cm of colon distal to the ileocaecal junction was resected. Metronidazole at 10 mg/kg and cephazolin at 20 mg/kg were continued post-operatively intravenously for 24 h and cephalexin (Ceporex; Shering-Plough Animal Health) at 20 mg/kg was administered orally for 5 days thereafter. Oral fluids were offered 12 h post-operatively and feeding commenced 24 h post-operatively. Analgesia was provided by buprenorphine (Vetergesic; Animal-care) at 10 μg/kg subcutaneously three times daily for 24 h. The cat made an uneventful recovery and was subsequently discharged 2 days later.

Grossly, the mass attached to the ileocaecal junction measured 4 cm in diameter. On histopathological examination, sections through the mass showed a densely cellular accumulation of neoplastic lymphocytes. Mitotic figures were frequent (>4 per high power field) and at the site of attachment of the mass, the intestinal wall was infiltrated by dense sheets of the same cell types. These features were present at the margins of both the ileum and colon and identified the disease as an alimentary lymphosarcoma.

The owner declined adjuvant chemotherapy and therefore the cat was palliated with a course of prednisolone (Prednicare; Animalcare Limited) at 1.5 mg/kg/day reducing to 1 mg/kg every other day until euthanasia was performed 3 months later.

An intussusception occurs when one portion of the gastrointestinal tract invaginates into the lumen of an immediately adjacent part causing complete or partial intestinal obstruction (Blood & Studdert 1988). The condition is seen mainly in young animals and may occur at any point of the gastrointestinal tract although ileocolic intussusceptions are reported to be the most common. This area represents a change in the diameter of the intestinal lumen which has been proposed as precursor for intussusception development.

Predisposing causes of intussusceptions have been cited to include intestinal parasitism, foreign bodies, previous abdominal surgery, virus-induced enteritis or mural lesions. In one series of 12 cats, five had an underlying intestinal disease or an intestinal linear foreign body. In the remaining seven cats no incriminating cause could be identified (Bellenger & Beck 1994). This finding is consistent with previous data which suggests that most intussusceptions are idiopathic (Wilson & Burt 1974). In this case the presence of the mass may have acted as a partial barrier to normal peristalic contractions, exacerbated by its location at the ileocaecal junction.

This case is particularly unusual in that it was the neoplasm that prolapsed through the anus as a result of the intussusception. It is more common to find an intussusception prolapsing through the anus and this can sometimes be mistaken for a rectal prolapse (Holt 1985). In this particular cat the invagination of the ileum into an abnormally narrow area of the ileocaecal junction led to complete obstruction of the lumen which resulted in the mass prolapsing when the cat strained to defecate. It seems likely therefore that the tumour predisposed to the development of the intussusception which in turn resulted in the tumour prolapsing. The diarrhoea reported initially may have been either a cause or an effect of the intussusception.

Enteroplication has been recommended to prevent recurrence of intussusceptions and without it recurrence rates of up to 27% have been reported in cases where a predisposing condition has not been found (Oakes et al 1994). In this case however, as the neoplasm was the most likely cause of the intussusception, it was hoped that its removal would prevent further intussusception.

In cats, lymphosarcoma is the commonest gastrointestinal neoplasm and constitutes 36% of reported cases of feline lymphosarcoma (Guildford & Strombeck 1996). It is particularly common at the ileocaecal junction. Treatment of this disease in cats is usually a combination of surgical resection and adjuvant chemotherapy with response rates of 30–60% and median remissions of 4–8 months (Guilford & Strombeck 1996). Further medical treatment was declined in this case and with only palliative treatment using prednisolone (Vanderhaar & Morrison 1998) the cat appeared to have a reasonable quality of life for 3 months after the surgery. Throughout this period the cat was producing soft but formed faeces and had maintained its weight up until the last week when it became inappetent. No recurrence of the intussusception was evident during this time.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Mr JW Simpson for performing the endoscopic examination in this case.

References

- Bellenger CR, Beck JA. (1994) Intussesception in 12 cats. Journal of Small Animal Practice 35, 295–298. [Google Scholar]

- Blood DC, Studdert VP, Carling RCJ. (1988) Baillièrés Comprehensive Veterinary Dictionary. London, Baillière Tindall, p. 496. [Google Scholar]

- Guilford WG, Strombeck DR, Strombeck DR. (1996/12) Small Animal Gastroenterology, 4th edn. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, pp. 519–525. [Google Scholar]

- Holt P. (1985) Anal and perianal surgery in the dog and cat. In Practice 7, 82–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis DD, Ellison GW. (1987) Intussusception in dogs and cats. Compendium of Continuing Education for the Practicing Veterinarian 9, 523–533. [Google Scholar]

- Oakes MG, Lewis DD, Hosgood G, Beale BS. (1994) Enteroplication for the prevention of intussusception recurrence in dogs: 31 cases (1978–1992). Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 205, 72–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderhaar MA, Morrison WB. (1998) Cancer in Dogs and Cats: Medical and Surgical Management, 1st edn. Maryland, Williams and Wilkins, pp. 667–695. [Google Scholar]

- Weaver AD. (1977) Canine intestinal intussusception. Veterinary Record 100, 524–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson GP, Burt JK. (1974) Intussusception in the dog and cat: A review of 45 cases. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 164, 515–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]