Abstract

Practical relevance Feline ‘lung–digit syndrome’ describes an unusual pattern of metastasis that is seen with various types of primary lung tumours, particularly bronchial and bronchioalveolar adenocarcinoma. Tumour metastases are found at atypical sites, notably the distal phalanges of the limbs; the weightbearing digits are most frequently affected, and multiple-digit and multiple-limb involvement is common. Often primary lung tumours in cats are not detected because of clinical signs referable to the primary tumour; rather, many cases present with signs referable to distant metastases. Other sites of metastases from feline primary lung tumours include the skin, eyes, skeletal muscle and bone, as well as multiple thoracic and abdominal organs. These lesions are thought to arise from direct arterial embolisation from the tumour. Indeed tumour embolisation to the aortic trifurcation is possible.

Patient group Primary lung neoplasms are uncommon in the cat. Older animals are most affected (mean age at presentation 12 years, range 2–20 years). There is no apparent sex or breed predilection.

Clinical challenges Feline lung–digit syndrome presents a diagnostic challenge. Typically there is swelling and reddening of the digit, purulent discharge from the nail bed, and dysplasia or fixed exsheathment of the associated nail. While these signs might be suggestive of infection, this could be secondary to a digital metastatic lesion, particularly in a middle-aged or elderly cat. Radiographic evidence of extensive bony lysis of the distal phalanx, which can be trans-articular to the second phalanx, raises the index of clinical suspicion for metastasis of a primary pulmonary tumour. Thoracic radiography is warranted prior to any surgery or digital amputation as the prognosis is generally grave for cats with this syndrome, with a mean survival time of only 58 days after presentation.

Evidence base This article reviews the previous literature and case reports of feline lung–digit syndrome and feline primary pulmonary neoplasia in general, discussing the course of this disease and the varying clinical presentations associated with different sites of metastasis.

Bacterial paronychia or something more sinister?

Nail and nail bed disorders are commonly seen in practice, particularly in older animals. The modern-day practitioner will be all too familiar with the presentation of an ageing or elderly cat with lameness associated with a swollen toe and a layer of purulent discharge around the nail and nail bed. This often occurs because there is less natural wearing of nails in older cats, leading to a thickened nail and secondary infection. Historically, bacterial paronychia has been recognised as the most common disorder affecting feline claws. 1 However, recent studies show that 1 in 8 cases of nail and nail bed disorders are due to neoplasia, and that the common presence of secondary infection leads to many an initial misdiagnosis. 2

Digits suffering from recurrent infections, or additional gross pathology, are frequently amputated. Significantly, however, a 2007 clinical study of 85 feline digits submitted for histopathology found that 63 showed evidence of neoplasia, with malignant disease affecting 60 (95%) of these cases. 3 Of the tumour types identified, squamous cell carcinoma and fibrosarcoma accounted for 24% and 22% of cases, respectively. However, 21% of the tumours identified were adenocarcinoma, presumed to represent metastatic spread from a primary pulmonary neoplasm: so-called feline ‘lung–digit syndrome’ (Figures 1–3). This syndrome describes a specific clinical presentation of feline primary lung neoplasia, particularly bronchogenic adenocarcinoma, which has metastasised to one or more digits.4,5 This suggests that roughly 1 in 6 laboratory submissions of an amputated feline digit contain a metastatic lesion, where the primary disease may not have been identified.

Figure 1.

(a) Metastatic lesion from a primary pulmonary adenocarcinoma in the digit of an elderly cat. The cat presented with lameness and clinically evident deviation of the nail, local soft tissue inflammation and a serosanguineous discharge from the nail bed. (b) Radiography revealed osteolysis of the associated phalanges (arrow)

Figure 3.

Gross appearance of neoplastic proliferation (arrowheads) within the caudal lung field of the cat in Figures 1 and 2

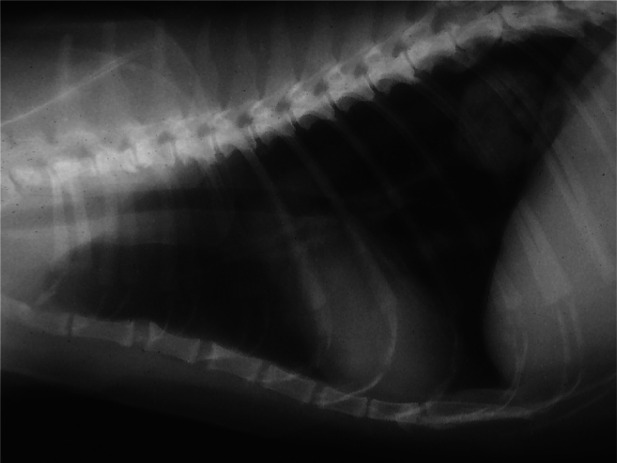

Figure 2.

A primary pulmonary neoplasm is evident within the caudal lung fields of the same cat as in Figure 1 on thoracic radiography (lateral view)

Clinical presentation

Metastatic tumours of the digit(s) can cause a variety of different local signs, although the affected animal commonly presents for lameness or painful paws. However, some cases show only minimal signs such as deviation or fixed exsheathment of the nail. 10 Multiple digits are commonly involved, and often on multiple paws. 4 In recent case reports and case series, the most commonly recognised gross clinical signs on presentation included swelling of the distal extremity of the digit, ulceration of the digital skin or nail bed, purulent discharge, and fixed exsheathment, deviation or loss of the nail.4,5,9,11 All digits may be involved, with the exception of the dew claws, in which this condition has not yet been recognised. 11 However, retrospective studies suggest that the weightbearing digits are most commonly affected. 11 Non-specific systemic clinical signs, such as malaise, inappetence, weight loss and pyrexia, are infrequently recognised in these cases. 10

Feline lung–digit syndrome appears to be more common in the elderly cat, with an average age at presentation of 12 years, although the condition has also been seen in much younger animals (range 4–20 years).4,9,11 There is no apparent sex or breed predisposition, and the syndrome has been recognised in many different purebred lines as well as in the typical moggy.9,11

Preliminary investigations

Given the potential differential diagnoses for cats with clinical signs on multiple digits such as described (see box on page 205 and Figure 4), what can help to identify lung–digit syndrome in practice?

Figure 4.

Metastases from primary lung tumours are not the only lesions that can affect the digit, or multiple digits, of cats. Infectious agents living in the environment (eg, Nocardia species, mycobacteria, fungi) and fastidious agents inoculated by biting rodents (rats, mice, voles) can also produce digital infections that tend to be granulomatous or pyogranulomatous in nature. Of course, these infections usually do not have associated lesions evident in chest radiographs, and cytology of aspirates or histology of excisional biopsies almost always reveals the aetiological agent. It is interesting that some infectious agents that spread haematogenously (like cryptococci) can also involve digits and other tissues that tend to be involved in the ‘lung–digit syndrome’. These images show (a and b) feline leprosy due to Mycobacterium lepraemurium; note the different severity in different toes of the same cat; (c and d) Nocardia species infections in two cats; (e) Cladosporium species infection; note that the lesion has a bluish hue imparted by the presence of this pigmented fungus in the cat’s tissues. Courtesy of Richard Malik (a–d), Joanna White (c and d) and Eamonn Lim (e)

Haematology and serum biochemistry

Complete blood counts and serum biochemistry profiles of affected cats are generally unremarkable.4,11 In some cases, non-specific changes such as anaemia (often non-regenerative) or leukocytosis (often neutrophilic) have been identified, 4 as well as biochemical changes such as azotaemia, which may be associated with further tumour metastases at different sites. 8 The vast majority of cases have tested negative for feline immunodeficiency virus and feline leukaemia virus. 4

Paraneoplastic disease was not thought to be involved with this condition, 11 although two recent case reports have suggested an association between hypercalcaemia and malignancy of feline bronchogenic carcinoma.12,13 Endogenous lipid (cholesterol) pneumonia has also been associated with feline bronchogenic carcinoma. 14

Radiography of the digits

Radiography of the digits reveals a classic picture of osteolysis of the third phalanx, with potential invasion of the intra-articular space (P2–P3) and also osteolysis of the second phalanx. 11 This is in marked contrast to the clinical picture in humans where phalangeal metastases do not show spread to neighbouring phalanges or intra-articular invasion. 17 In some feline cases, periosteal proliferation has been seen on all phalanges of the affected foot. 11

Thoracic radiography

Thoracic radiography will, in many cases, identify or suggest an underlying pulmonary neoplasm, and should always be considered prior to surgery or digital amputation.9,11 The classic radiographic appearance of feline primary pulmonary neoplasia is a solitary circumscribed mass in the caudal lung lobes.4,8 However, cases of primary feline neoplasia may present in a number of ways in any, or multiple, lung lobes: a single circumscribed mass, multiple circumscribed masses, lobar consolidation or in a diffuse pattern. Associated pleural effusion may be seen, often causing respiratory compromise.6,8,11,18 Enlargement of the tracheobronchial lymph nodes may also be evident.4,8,18

In some cases, however, the primary neoplastic lesion may not be visible radiographically. 6

Confirmation of diagnosis

Clinical signs and radiography can provide a high index of suspicion for lung–digit syndrome, and, given the associated poor prognosis, many cats are euthanased at this stage. But, in those difficult clinical situations, what can you do to confirm this condition?

True proof of metastatic spread of a pulmonary neoplasm to the digits relies on histopathological confirmation of the same tumour type in both sites, but you need to ensure that you collect appropriate material from these sites, which can often prove difficult to sample.

Digital biopsy samples

To sample the digit, there are essentially four options:

Needle aspirate of the digit (easy to perform but extremely unlikely to provide enough material to allow a good histopathological diagnosis);

Punch or incisional biopsies of affected (eg, ulcerated) tissue;

Avulsed nail;

Full digit amputation.

Any of the first three options may allow disease confirmation, but it is important to note that in a high number of samples neoplastic material may not be identified.1,11 The gold standard for histopathological diagnosis is full digit amputation,3,5 particularly if longitudinal sections are requested; 4 albeit there are obvious drawbacks associated with surgery in a case that may ultimately have a very poor prognosis.

Bacterial (aerobic and anaerobic) and fungal culture from the biopsy sample may also be relevant, and sometimes aspirate cytology can identify saprophytic pathogens (eg, Nocardia species and mycobacteria).4,19–21

Thoracic biopsy samples

Confirmation of pulmonary neoplasia can often be made based on thoracocentesis of pleural effusion, cytology of tracheal washes or bronchoscopic samples, or fine-needle aspiration of a lung mass. However, as with digital samples, biopsies that include the original tissue architecture are generally required to give a complete diagnosis, including site of origin; this is only achieved with lobar resection or on post-mortem examination.5,8,18,22

Pathophysiology

Histopathology of these tumours typically demonstrates highly cellular material with clumps, strands or cords of large mononuclear cells with epithelial morphology. Ciliated epithelial cells, as well as goblet cells, are commonly seen.8–11 Frequent cytoplasmic vacuoles are suggestive of secretory tumours (adenocarcinoma). 8 Signs of inflammation, including degenerate neutrophils, are often found, suggesting inflammation secondary to necrosis. 23 Metastatic lesions are often associated with extensive fibrosis.9,11 In digital lesions, neoplastic cells are most frequently found in the dermis, the dorsal aspect of the digit, or ventral to the footpad.4,11 Demonstration of pulmonary cellular features (ciliated epithelia, goblet cells, periodic acid Schiff-positive secretory material) and some cellular markers (positive staining for CAM 5.2 antibody against keratin) can be used to identify digital tumours as metastatic.4,9

The apparent increased frequency of metastatic spread of feline pulmonary neoplasms to the digits, in comparison with other sites and other species, is due to the angioinvasive properties of these lesions, and subsequent haematological spread. Tumour cells have been frequently identified within the pulmonary and digital arteries in histopathological samples.5,9 It has also previously been established that cats have a high digital blood flow to facilitate heat loss, and it is hypothesised that this explains the increased metastatic rate of tumours to these sites. 24 However, additional factors, such as cell markers or chemical secretions, may also play a role in the pathophysiology of this syndrome.4,25

Treatment and prognosis

The prognosis for a cat with lung–digit syndrome is grave.6,11 One study revealed a median survival time of 67 days after presentation (mean 58 days, range 12–122 days); the majority of cats were euthanased due to persistent lameness, lethargy or anorexia. 11

No effective treatment has yet been demonstrated for feline metastatic digital carcinoma. Amputation has not been shown to be palliative, as further metastases rapidly develop. 11 However, where there is no evidence of metastatic disease, solitary lung neoplasms may be surgically resected. Previous studies have demonstrated a median post-surgery survival time of 698 days for cats with well-differentiated tumours; survival time following resection of poorly differentiated lung tumours had a median of only 75 days. 18 The degree of differentiation of the pulmonary neoplasm has, therefore, been suggested to be a prognostic indicator following surgery. 18 Chemotherapy with mitoxantrone following lobar resection has been documented in some case studies. 22

Other sites of metastases from pulmonary neoplasms

Many other sites of metastases from feline primary pulmonary neoplasms have been identified, including the skin, eyes (fundus), skeletal muscles and bone, as well as more ‘common’ sites of metastases, such as the liver, spleen, kidneys, intestines, lungs and brain.5,8–10 Clinical features in these cases are associated with the site of metastasis: cutaneous lesions are frequently found on the dorsum (and have been loosely termed feline ‘lung–back syndrome’),28,29 ocular lesions tend initially to present as ischaemic areas on the fundus and may lead to blindness,30–33 and musculoskeletal and bone lesions commonly cause lameness and limb pain.34–36 In all cases, a thorough clinical examination and thoracic radiography should suggest the primary aetiology, and this may be confirmed through histopathology.

Key points

Primary pulmonary neoplasia is not common in cats, but lesions tend to be malignant and carry a poor prognosis. Clinical signs often relate to tumour metastases, including spread to a number of unusual places, such as bone, skeletal muscle, skin, eyes and brain.

Feline lung–digit syndrome describes a clinical syndrome of metastasis of primary pulmonary neoplasia to one or more digits. Up to 1 in 5 cases of feline digital neoplasia may represent metastatic disease.

Clinical signs of lung–digit syndrome are often lameness, digital swelling, purulent nail bed discharge and dysplasia or fixed exsheathment of the nail.

Multiple digits, often on multiple limbs, are affected.

Thoracic radiographs are a vital diagnostic tool in any cat in which there is an index of clinical suspicion of lung–digit syndrome.

An important differential diagnosis is pyogranulomatous inflammation due to atypical pathogens, including fungi, Nocardia species and mycobacteria.

The prognosis is grave, with a mean survival time of 58 days after presentation, and digital amputation is non-palliative.

Funding

The authors received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors for the preparation of this review article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- 1. Scott DW, Miller WH. Disorders of the claw and clawbed in cats. Comp Contin Educ Pract Vet 1992; 14: 449–457. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Withrow SJ, Vail DM. Withrow and MacEwen’s Small animal clinical oncology. 4th ed. Oxford: Saunders, Elsevier, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wobeser BK, Kidney BA, Powers BE, et al. Diagnoses and clinical outcomes associated with surgically amputated feline digits submitted to multiple veterinary diagnostic laboratories. Vet Pathol 2007; 44: 362–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hanselman BA, Hall JA. Digital metastasis from a primary bronchogenic carcinoma. Can Vet J 2004; 45: 614–616. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jacobs TM, Tomlinson MJ. The lung-digit syndrome in a cat. Feline Pract 1997; 25: 31–36. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Barr F, Gruffydd-Jones TJ, Brown PJ, Gibbs C. Primary lung tumours in the cat. J Small Anim Pract 1987; 28: 1115–1125. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Moulton JE, von Tscharner C, Schneider R. Classification of lung carcinomas in the dog and cat. Vet Pathol 1981; 18: 513–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hahn KA, McEntee MF. Primary lung tumors in cats: 86 cases (1979–1994). J Am Vet Med Assoc 1997; 211: 1257–1260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. van der Linde-Sipman JS, van den Ingh TS. Primary and metastatic carcinomas in the digits of cats. Vet Q 2000; 22: 141–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. May C, Newsholme SJ. Metastasis of feline pulmonary carcinoma presenting as multiple digital swelling. J Small Anim Pract 1989; 30: 302–310. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gottfried SD, Popovitch CA, Goldschmidt MH, Schelling C. Metastatic digital carcinoma in the cat: a retrospective study of 36 cats (1992–1998). J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2000; 36: 501–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Anderson TE, Legendre AM, McEntee MM. Probable hypercalcemia of malignancy in a cat with bronchogenic adenocarcinoma. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2000; 36: 52–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schoen K, Block G, Newell SM, Coronado GS. Hypercalcemia of malignancy in a cat with bronchogenic adenocarcinoma. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2010; 46: 265–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jerram RM, Guyer CL, Braniecki A, Read WK, Hobson HP. Endogenous lipid (cholesterol) pneumonia associated with bronchogenic carcinoma in a cat. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 1998; 34: 275–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ibarrola P, German AJ, Stell AJ, Fox R, Summerfield NJ, Blackwood L. Appendicular arterial tumor embolization in two cats with pulmonary carcinoma. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2004; 225: 1065–1069, 1048–1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sykes JE. Ischemic neuromyopathy due to peripheral arterial embolization of an adenocarcinoma in a cat. J Feline Med Surg 2003; 5: 353–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nagendran T, Patel MN, Gaillard WE, Imm F, Walker M. Metastatic bronchogenic carcinoma to the bones of the hand. Cancer 1980; 45: 824–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hahn KA, McEntee MF. Prognosis factors for survival in cats after removal of a primary lung tumor: 21 cases (1979–1994). Vet Surg 1998; 27: 307–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Barfield D, Rich S, Pegrum S, Malik R. What is your diagnosis? J Small Anim Pract 2007; 48: 353–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Malik R, Hughes MS, James G, Martin P, Wigney DI, Canfield PJ, et al. Feline leprosy: two different clinical syndromes. J Feline Med Surg 2002; 4: 43–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Malik R, Krockenberger MB, O’Brien CR, White JD, Foster D, Tisdall PL, et al. Nocardia infections in cats: a retrospective multi-institutional study of 17 cases. Aust Vet J 2006; 84: 235–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Clements DN, Hogan AM, Cave TA. Treatment of a well differentiated pulmonary adenocarcinoma in a cat by pneumonectomy and adjuvant mitoxantrone chemotherapy. J Feline Med Surg 2004; 6: 199–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Corr SA, Blackwood L. What is your diagnosis? Primary pulmonary tumour (carcinoma) with digital metastases. J Small Anim Pract 2003; 44: 201, 240–xiii. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Moore AS, Middleton DJ. Pulmonary adenocarcinoma in three cats with nonrespiratory signs only. J Small Anim Pract 1982; 23: 501–509. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Scott-Moncrieff JC, Elliott GS, Radoveky A, Blevins WE. Pulmonary squamous cell carcinoma with multiple digital metastases in a cat. J Small Anim Pract 1989; 30: 696–699. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Marino DJ, Matthiesen DT, Stefanacci JD, Moroff SD. Evaluation of dogs with digit masses: 117 cases (1981–1991). J Am Vet Med Assoc 1995; 207: 726–728. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fukuma H, Beppu Y, Chuma H, Egawa S, Oyamada H, Terui S. Diagnosis and treatment of metastatic bone cancer of the extremities [Japanese]. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho 1987; 14: 1729–1738. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Favrot C, Degorce-Rubiales F. Cutaneous metastases of a bronchial adenocarcinoma in a cat. Vet Dermatol 2005; 16: 183–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Petterino C, Guazzi P, Ferro S, Castagnaro M. Bronchogenic adenocarcinoma in a cat: an unusual case of metastasis to the skin. Vet Clin Pathol 2005; 34: 401–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cassotis NJ, Dubielzig RR, Gilger BC, Davidson MG. Angioinvasive pulmonary carcinoma with posterior segment metastasis in four cats. Vet Ophthalmol 1999; 2: 125–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gionfriddo JR, Fix AS, Niyo Y, Miller LD, Betts DM. Ocular manifestations of a metastatic pulmonary adenocarcinoma in a cat. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1990; 197: 372–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Heider HJ, Loesenbeck G, Heider E, Drommer W. Intraocular metastasis of bronchial carcinoma in a cat [German]. Tierarztl Prax 1997; 25: 271–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sandmeyer LS, Cosford K, Grahn BH. Metastatic carcinoma in a cat. Can Vet J 2009; 50: 95–96. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jensen HE, Arnbjerg J. Bone metastasis of undifferentiated pulmonary adenocarcinoma in a cat. Nord Vet Med 1986; 38: 288–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Langlais LM, Gibson J, Taylor JA, Caswell JL. Pulmonary adenocarcinoma with metastasis to skeletal muscle in a cat. Can Vet J 2006; 47: 1122–1123. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nakanishi M, Kuwamura M, Ueno M, Yasuda K, Yamate J, Shimada T. Pulmonary adenocarcinoma with osteoblastic bone metastases in a cat. J Small Anim Pract 2003; 44: 464–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]