Abstract

An adenocarcinoma of the disseminated prostate gland with pulmonary, myocardial and renal metastases is described in a 12-year-old, neutered male European cat. Histologically, the tumour was localised in the spongy layer of the prostatic urethra and showed an epithelial alveolar pattern. Considering the anatomic, microscopic and immunohistochemical findings, the tumour was diagnosed as an adenocarcinoma of the disseminated prostate gland. To our knowledge this is the first report of adenocarcinoma of the disseminated prostate gland in a cat.

The prostate is an accessory sexual gland present in all male mammals. It is composed of two anatomical sections: the body (or external part), situated around the cranial part of the pelvic urethra, and the disseminated (or diffuse) part, located in the submucosa (Banks 1993, Aughey and Frye 2001). The development of the two portions varies in the different species. In carnivores and stallions the body is prevalent. However, in bulls and small ruminants, the diffuse portion is more developed (Banks 1993). In male cats, the urethra measures between 8.5 and 10.5 cm in length. The prostatic urethra measures between 1.5 and 1.9 cm and traverses ventrally through the prostate (diameter 0.45–0.5 cm) (Wang et al 1999). Prostatic pathology is very rare in the cat but neoplastic processes have been described (Hubbard et al 1990, Caney et al 1998, LeRoy and Lech 2004). To our knowledge, this is the first report of an adenocarcinoma of the disseminate part of prostatic gland with pulmonary, myocardial and renal metastases.

A 12-year-old, neutered male, domestic shorthaired cat was presented to the referring veterinarian with a history of inappetence, continued weight loss and weakness. The cat tested positive for feline immunodeficiency virus. Upon physical examination, the cat was found to be depressed and restless. The clinical signs were dysuria, haematuria and severe dyspnoea. The cat was in a very poor general condition. The owner did not give consent for further clinical diagnostic examination and because of rapid progression of the clinical signs, the animal was euthanased.

At necropsy, the cat was found to be in a poor nutritional condition. In the lungs, there were multiple, firm and white nodules, ranging from 0.5 to 1.5 cm in diameter scattered in the caudal lobes. The pulmonary nodules were close to mediastinal lymph nodes, and they were also infiltrated. A white nodule of 0.8 cm in diameter was also visible on the free wall of the left cardiac ventricle. The urinary bladder was distended. Three centimetres caudally, the prostatic urethra was moderately thickened in diameter (for about 1 cm in length) with a greyish colour on the external surface and on cut serial sections. There were no lesions in the urinary bladder and pelvic urethral mucosa.

Tissue samples from all major organs and tumour masses were fixed in 10% buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin wax, and sectioned at 4 μm thickness. Deparaffinised sections were stained with haematoxylin and eosin (HE). Additional sections of the urethra, pulmonary and miocardial nodules were also subjected to immunohistochemistry using primary monoclonal mouse anti-human antibody anti-cytokeratin 7 (CK7; DAKO, clone OV-TL 12/30, dilution 1:75).

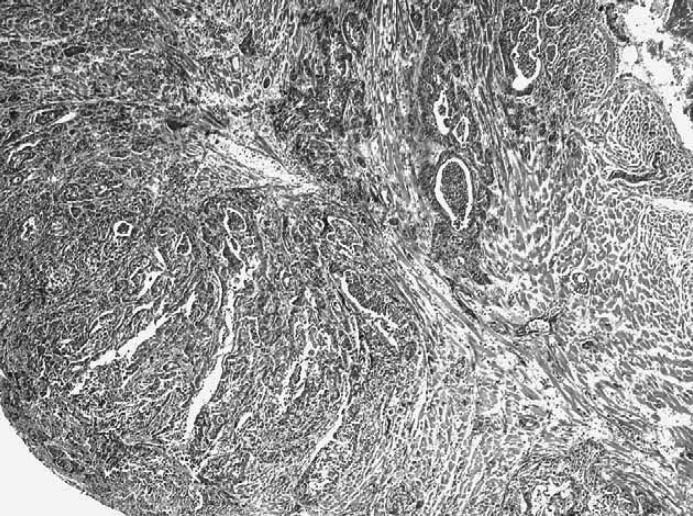

Histopathological examination of multiple serial sections of the prostatic urethra showed in the spongy layer an unencapsulated, infiltrative, and intramural neoplasia, involving the urethral muscle. Urothelial mucosa was normal (Fig. 1).

Fig 1.

Prostatic urethra of the cat showing infiltrative and intramural alveolar adenocarcinoma in the spongy layer without urothelial involvement. HE: ×40. Insert: alveolar structure formed by neoplastic epithelial cells surrounded by desmoplasia. HE: ×200.

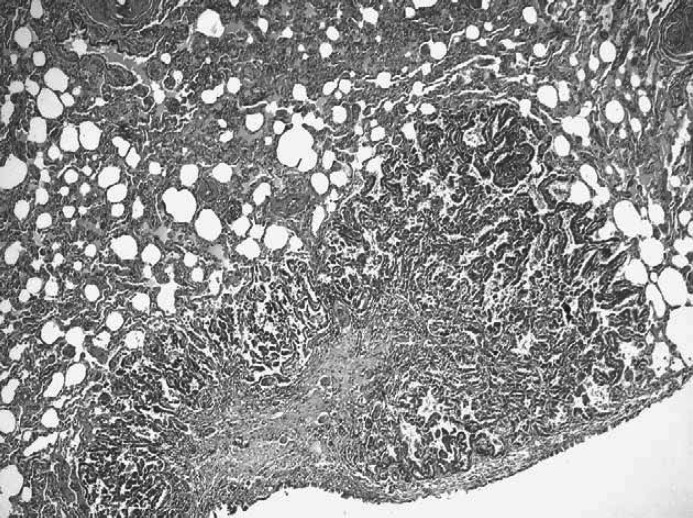

The tumour was characterised by alveolar structures, separated by a fibrous connective tissue stroma and contained moderately to markedly pleomorphic epithelial cells (Fig. 1, insert). Neoplastic cells, grouped in solid sheets, were round to oval, 60–75 μm in diameter and arranged in papillary and stratified structures. Tumour cells were characterised by an abundant pale and eosinophilic cytoplasm, and a hyperchromatic oval nucleus with 1–2 distinct nucleoli. Mitotic figures were common, ranging from two to five per high-power field (400×) and atypical to bizarre mitoses were frequently observed. Intralesional multifocal haemorrhages and necrotic areas were observed. In the prostatic urethra, tumour emboli were present. Neoplastic nodules in the myocardium (Fig. 2) and lung (Fig. 3) were histologically similar to the primal neoplasia and they showed less differentiated acinar formations. In the medulla of the left kidney a single metastasis was also present. Immunohistochemical studies demonstrated negative staining for CK7 in the prostatic neoplasia, while positive staining in the normal urethral epithelium was present.

Fig 2.

Myocardium of the free wall of the left ventricle in the cat showing multifocal epithelial alveolar metastases. HE: ×100.

Fig 3.

Caudal lobe of the cat's lung showing focal epithelial alveolar metastasis. HE: ×100.

The topographical, histopathological and immunohistochemical findings indicate an adenocarcinoma of the disseminated part of the prostate gland with pulmonary, myocardial and renal metastases.

Prostatic carcinomas are rare in the cat and uncommon in other species. The exact incidence of primary prostate carcinoma is unknown, because prostatic invasion by urothelial carcinoma originating from transitional epithelium of the prostatic urethra or from the periurethral ducts is frequent. In order to differentiate the origin of the neoplasia, it is important to perform an accurate macroscopic examination and immunohistochemistry (MacLachlan and Kennedy 2002). Previous work in the cat demonstrated that 75% of urothelial carcinomas are positive for CK7 and CK20 (Espinosa de los Monteros et al 1999).

In the present report, topographical localisation proved the prostatic origin. The origin of neoplasia from the bulbourethral gland was excluded because the lesion was localised in the prostatic urethra, 3 cm caudally to the bladder, therefore, cranially to bulbourethral region. In our case, the absence of lesions in the urinary bladder and in the urethral mucosa excludes the urothelial origin of carcinoma. Thus, the histology and, especially, the negative staining for CK7-immunohistochemistry, confirm our diagnosis. The differential diagnosis for the localisation of the neoplasia included transitional cell carcinoma, potentially responsible for severe urinary tract disorders. In the cat, transitional cell carcinomas are usually located in the bladder (fundus, ventral wall or neck) (Wimberly and Lewis 1979).

Nevertheless, some reports describe urethral transitional cell carcinoma (Barrett and Nobel 1976, Takagi et al 2005).

Previous reports of prostatic carcinoma in the cat do not specify the anatomical part of the prostate gland involved. Animals were neutered and characterised by particularly aggressive neoplasia; the age range of affected animals was 6–12 years. Metastases were reported in the main organs, but not in the regional lymph nodes (Hubbard et al 1990, Caney et al 1998, LeRoy and Lech 2004). The presence of an invasive mass in the prostatic urethra was also described.

In our case, clinical signs (dysuria) were not correlated with a mass but with an intramural, infiltrative prostatic adenocarcinoma growth in the prostatic urethra that was responsible for a moderate thickening of the wall. In conclusion, based on topographical, histopathological and immunohistochemical examination, this tumour was diagnosed as adenocarcinoma in the disseminate prostate. To our knowledge, this is the first case report of adenocarcinoma in the disseminated prostate in mammals.

References

- Aughey E., Frye F.L. Male reproductive system, Comparative Veterinary Histology, 2001, Manson Publishing: London, pp. 167–182 [Google Scholar]

- Banks William J. Male reproductive system, Applied Veterinary Histology, 3rd edn, 1993, Mosby – Year Book: St Louis, pp. 429–445 [Google Scholar]

- Barrett R.E., Nobel T.A. Transitional cell carcinoma of the urethra in a cat, Cornell Veterinarian 66, 1976, 14–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caney S.M., Holt P.E., Day M.J., Rudorf H., Gruffydd-Jones T.J. Prostatic carcinoma in two cats, Journal of Small Animal Practice 39, 1998, 140–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de los Monteros A. Espinosa, Fernández A., Millán M.Y., Rodríguez F., Herráez P., de las Mulas J. Martín. Coordinate expression of cytokeratins 7 and 20 in feline and canine carcinomas, Veterinary Pathology 37, 1999, 179–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard B.S., Vulgamott J.C., Liska W.D. Prostatic adenocarcinoma in a cat, Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 197, 1990, 1493–1494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeRoy B.E., Lech M.E. Prostatic carcinoma causing urethral obstruction and obstipation in a cat, Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery 6, 2004, 397–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLachlan N.J., Kennedy P.C. Tumors of the genital system. Meuten Donald J. Tumors in Domestic Animals, 2002, Iowa State Press, 547–572. [Google Scholar]

- Takagi S., Kadosawa T., Ishiguro T., Ohsaki T., Okumura M., Fujinaga T. Urethral transitional cell carcinoma in a cat, Journal of Small Animal Practice 46, 2005, 504–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B., Bhadra N., Grill W.M. Functional anatomy of the male feline urethra: morphological and physiological correlations, Journal of Urology 161, 1999, 654–659. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wimberly H.C., Lewis R.M. Transitional cell carcinoma in the domestic cat, Veterinary Pathology 16, 1979, 223–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]