Abstract

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) are increasingly being proposed as a therapeutic option for a variety of different diseases in human and veterinary medicine. At present, MSC are most often collected from bone marrow (BM) or adipose tissue (AT) and enriched and expanded in vitro before being transferred into recipients. However, little is known regarding the culture characteristics of feline BM-derived (BM-MSC) versus AT-derived MSC (AT-MSC). We compared BM-MSC and AT-MSC from healthy cats with respect to in vitro growth and cell surface phenotype. Mesenchymal stem cells isolated from AT proliferated significantly faster than BM-MSC. Phenotypic differences between BM-MSC and AT-MSC were not present in the surface markers assessed. We conclude that BM-MSC and AT-MSC are similar phenotypically but that cultures of AT-MSC are easier to generate because of their higher intrinsic proliferative rate. Thus, AT-MSC may be the preferred MSC for clinical applications where rapid and efficient generation of MSC is important.

Short Communication

Mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) therapy is being proposed as a therapeutic option for treatment of a variety of different diseases. Mesenchymal stem cells possess many characteristics that make them attractive for cellular therapy. For example, they can be derived from a variety of adult tissues, are relatively non-immunogenic, and have immunosuppressive properties that show promise in many immune and inflammatory disease processes.1,2 The ability of MSCs to stimulate healing and suppress inflammation makes them attractive for use in cats with chronic inflammation or degenerative diseases, such as inflammatory bowel disease and osteoarthritis.

Although bone marrow (BM) is the traditional source of MSC, the number, frequency, and differentiation capacity of BM-MSC has been shown to decrease significantly with age.3,4 Consequently, MSC derived from adipose tissue (AT-MSC) have received increased attention because these cells can be obtained more easily and in greater numbers from donor animals than BM-MSC.5–7 Several prior studies have shown that human AT-MSC are similar to BM-MSC depending on the intended application.5,6,8–10

Currently, there is little information on the phenotype or function of MSCs generated from cats. In 2002, Martin et al described the isolation and characterization of feline BM-MSC. 11 Jin et al have evaluated the potential for feline umbilical cord blood-derived MSCs and BM-MSCs to differentiate into or affect neuronal tissue as a means of evaluating MSC use in neurodegenerative diseases, such as Parkinson’s disease.12,13 Another study reported that c-Kit+ feline BM cells had the potential to differentiate into functional cardiac myocytes. 14 We recently reported that autologous feline BM-MSCs and AT-MSCs could be safely transplanted unilaterally into the renal cortex of cats with chronic kidney disease and that AT-MSCs were considerably easier to generate from older cat donors than BM-MSCs. 15 However, there are currently no published studies that systematically compare AT-MSCs with BM-MSCs from cats with respect to ease of culture or phenotypic properties. Consequently, we conducted a study comparing the growth properties and phenotype of feline BM-MSC and AT-MSC obtained by bone marrow aspirate and inguinal fat pad biopsy from four healthy, young, donor cats.

Four young adult (range 19–36 months, average = 26 months), specific pathogen-free (SPF) cats were used for the study. The SPF cats were purchased from a commercial research laboratory (Liberty Labs) and were raised under SPF conditions, and we therefore consider the MSCs to also be free from important cat pathogens. All animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Colorado State University, and the study cats were adopted to private homes after study completion. For sample collection, cats were sedated with ketamine (Fort Dodge, Fort Dodge, IA, USA; 10–20 mg/cat, IV), midazolam (Baxter HealthCare, Deerfield, IL, USA; 0.1 mg/kg, IV), and butorphanol (Fort Dodge, 0.1 mg/kg IV).

For BM aspiration, the skin was shaved and prepped with chlorhexiderm solution and isopropyl alcohol, and lidocaine (Vedco; Saint Joseph, MO, USA; 0.5 ml) was administered subcutaneously at the site of skin puncture. Approximately 1 ml of BM was collected from the proximal humerus of each animal into a heparin-coated syringe using an 18-gauge bone marrow needle. The sample was suspended in culture medium and placed directly into tissue culture flasks. The culture medium consisted of low-glucose DMEM (Invitrogen/Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with penicillin (Invitrogen/Gibco; 100 U/ml), streptomycin (Invitrogen/Gibco; 100 µg/ml), L-glutamine (Invitrogen/Gibco; 2 mM), 1% essential amino acids without L-glutamine (Invitrogen/Gibco), 1% non-essential amino acids (Invitrogen/Gibco; 1% bicarbonate solution (Invitrogen/Gibco; 7.5%)), and 15% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; Cell Generation, Fort Collins, CO, USA). The cells were incubated for 48 h at 37°C and 5.0% CO2, after which the non-adherent cells were removed and fresh medium was added. The remaining plastic-adherent cells were incubated until approximately 70% confluent with media changes every 2–3 days. The cells were then rinsed with Dulbecco’s phosphate buffered saline (D-PBS; Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) and detached using 0.25% trypsin-EDTA (Invitrogen/Gibco) for passage to larger flasks to allow for additional expansion.

Adipose tissue was obtained from sedated animals using a sterile 8 mm punch biopsy at a site on the ventral abdomen just caudal to the umbilicus. The biopsy site was shaved and prepped with chlorhexiderm solution and isopropyl alcohol, and the biopsy site was sutured closed after tissue collection. The skin was removed from the AT, and the AT was then minced using a sterile scalpel blade, digested with collagenase (Sigma Aldrich; 1 mg/ml) for 30 min at 37°C, and centrifuged (1200 rpm/380 x g, 5 min) to separate the stromal vascular fraction (SVF) from the remaining adipocytes. 16 The SVF was washed in D-PBS and plated in MSC medium in tissue culture flasks and expanded as described above for BM-MSC cultures.

Mesenchymal stem cells from low-passage cultures of BM (passage 2–3) or AT (passage 4–5) were characterized by surface marker expression using flow cytometry and a panel of cross-reactive antibodies specific for surface determinants expressed by MSCs from other species. Specifically, MSCs were analyzed for surface expression of CD44 (antibody clone: IM7; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA), CD105 (antibody clone: SN6; BD Biosciences), and CD90 (antibody clone: eBio5E10; BD Biosciences). 15 The MSC were also assessed for expression of CD4 (antibody clone: 3-4F4; Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL, USA) and MHC class II (antibody clone: TÜ39; BD Biosciences). 17 For immunostaining, MSC were trypsinized, washed, re-suspended in FACS buffer (PBS, 2% FBS, and 0.01% sodium azide (Invitrogen/Gibco)), and incubated with each antibody or appropriate isotype control for 30 min at room temperature. Samples were then washed, re-suspended in FACS buffer, and stored at 4°C prior to analysis. Samples were assessed for surface binding of antibodies using a Cyan ADP flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA). At least 25,000 events were collected for analysis per sample. Statistical analysis of data was performed using a Wilcoxon sign rank test with Prism5 software from Graphpad Software (LaJolla, CA, USA). The data were not normalized.

Cell proliferation was analyzed using a standard MTT assay. 18 For the proliferation assay, 5000 MSC in 100 µl MSC medium were added per well to a 96-well flat bottom tissue culture plate in triplicate. After 1, 24, 72, and 120 h incubation times, MTT solution (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrasolium bromide, Sigma Aldrich) was added to each well, and the plates were incubated for 4 h. After 4 h, 0.1N HCl in isopropanol was added to each well to dissolve the formazan product. Formazan production was quantified by measuring the absorbance on a spectrophotometer (Synergy HT; Bio-Tek, Winooski, VT). Triplicate absorbance values were averaged, and a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni post hoc analysis was performed using Prism5 software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA).

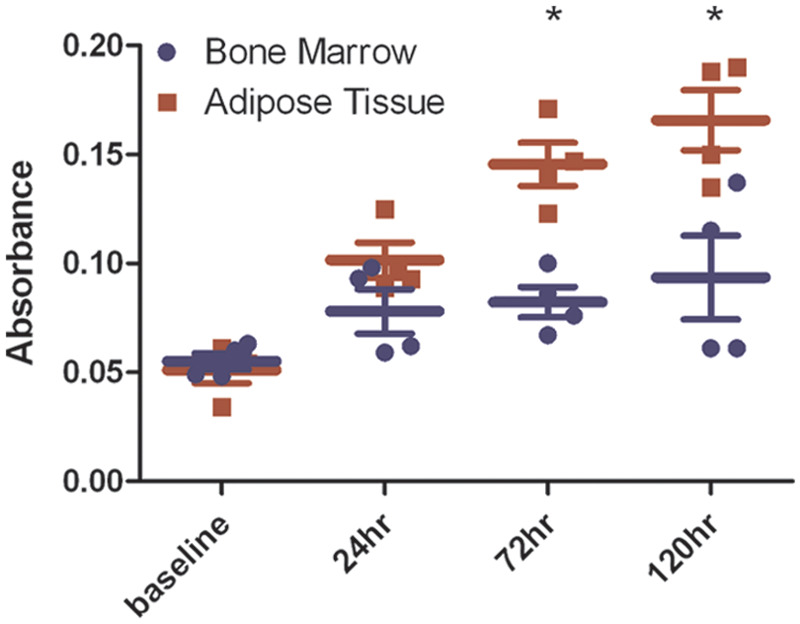

Samples of BM and AT generated plastic-adherent, spindle-shaped cells within 24–72 h of culture. We found that the replication rate of AT-MSCs was significantly greater than that of BM-MSCs, as reflected by significantly higher cell numbers for AT-MSC cultures after 72 (P <0.01) and 120 h (P <0.001) in culture (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Feline adipose tissue-derived MSCs (AT-MSCs) proliferate more rapidly than bone marrow-derived MSCs (BM-MSCs) from the same animals after 72 and 120 h in culture. Proliferation of AT-MSCs and BM-MSCs was measured by standard MTT assay in triplicate at baseline (1 h), 24, 72, and 120 h (*= P <0.01). Results are representative of two separate experiments. Culture time (hours) is shown on the x axis, and average absorbance value is shown on the y axis

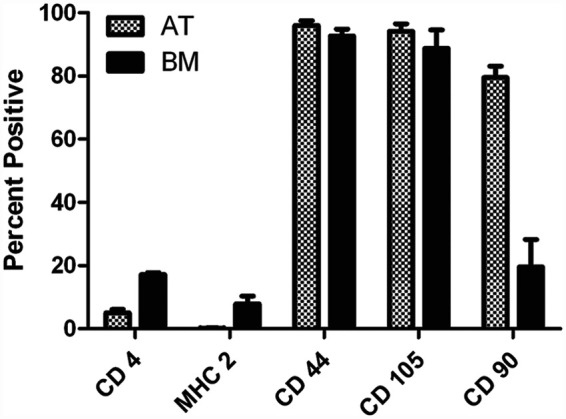

We also compared the cell surface phenotype of BM-MSCs and AT-MSCs using flow cytometry to assess expression of cell surface markers typically associated with MSCs from other species. The percentage of cells expressing CD44, CD90, CD105, CD4, and MHC class II was compared between BM-MSCs and AT-MSCs, and no statistically-significant differences were found. We found that MSCs from both sources expressed similar high levels of CD44 and CD105, and very low levels of CD4 and MHC class II (Figure 2). Although AT-MSCs consistently contained a higher percentage of cells that expressed CD90 when compared with BM-MSCs, the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.1250).

Figure 2.

Feline adipose-derived MSCs (AT-MSCs) demonstrate similar surface marker expression as feline bone marrow-derived MSCs (BM-MSCs). Primary cultures of feline MSCs were passaged 2–5 times, collected by trypsinization, and immunostained for assessment of CD4, MHC class II, CD44, CD105, and CD90 percent expression by flow cytometry. Data is representative of two separate experiments (n = 4). The specific surface marker examined is listed on the x axis, and the average percent expression is shown on the y axis

Based on these studies, we conclude that AT-MSC can be generated more efficiently and more quickly from cats than BM-MSCs and that the two MSC populations are phenotypically very similar. Our studies revealed that AT-MSC had significantly higher proliferation rates than BM-MSC, which is similar to reports from other species.8,19,20 The phenotype of feline AT-MSC generated in our study was very similar to that reported previously for BM-MSCs from cats and other species.1,5,11,21–23 The presence of CD4+ cells, particularly in the BM-MSCs in our study, is not typically reported and is likely caused by the presence of residual BM lymphocytes in early-passage BM samples. It should be noted that for human MSCs, some groups have reported distinct differences in CD34, PODXL, CD36, CD49f, CD106, and CD146 expression by AT-MSCs and BM-MSCs.10,24,25

Mesenchymal stem cells have also been functionally characterized by their ability to undergo tri-lineage differentiation and to suppress mitogen-induced T cell proliferation in vitro.5,21,25–27 We found that both AT-MSCs and BM-MSCs were capable of undergoing differentiation into chondrocytes, osteoblasts, and adipocytes in vitro, as we reported previously. 15 Although consistent with findings for other species, the findings in this study are limited by the small sample number (n = 4) and the amount of tissue available for examination from each cat. Evaluation of a larger number of animals would be necessary to confirm the preliminary findings presented here.

The therapeutic potential of MSCs depends, to a large degree, on our ability to generate large numbers of MSC relatively quickly in vitro. Therefore, AT-MSCs offer significant advantages over BM-MSCs in this regard, at least for generating MSCs from cats. The use of AT-MSCs rather than BM-MSCs also allows easier collection and a larger source of cells that can be collected in a relatively non-traumatic manner. Our research group is currently exploring the therapeutic potential for AT-MSCs to be used in the treatment of feline chronic kidney disease based on early promising results from pilot studies. 15

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Michael Lappin for providing the SPF cats used in this study.

Funding

These studies were supported, in part, by grant K08AI071724 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease, by a grant from the Winn Feline Foundation, and by a grant from the Morris Animal Foundation. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases or the National Institutes of Health.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- 1. Yarak S, Okamoto OK. Human adipose-derived stem cells: current challenges and clinical perspectives. An Bras Dermatol 2010; 85: 647–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Uccelli A, Moretta L, Pistoia V. Mesenchymal stem cells in health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol 2008; 8: 726–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Stenderup K, Justesen J, Clausen C, et al. Aging is associated with decreased maximal life span and accelerated senescence of bone marrow stromal cells. Bone 2003; 33: 919–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nishida S, Endo N, Yamagiwa H, et al. Number of osteoprogenitor cells in human bone marrow markedly decreases after skeletal maturation. J Bone Miner Metab 1999; 17: 171–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kern S, Eichler H, Stoeve J, et al. Comparative analysis of mesenchymal stem cells from bone marrow, umbilical cord blood, or adipose tissue. Stem Cells 2006; 24: 1294–1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dicker A, Le Blanc K, Astrom G, et al. Functional studies of mesenchymal stem cells derived from adult human adipose tissue. Exp Cell Res 2005; 308: 283–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kronsteiner B, Wolbank S, Peterbauer A, et al. Human mesenchymal stem cells from adipose tissue and amnion influence T-cells depending on stimulation method and presence of other immune cells. Stem Cells Dev 2011; 267: 30–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zhu Y, Liu T, Song K, et al. Adipose-derived stem cell: a better stem cell than BMSC. Cell Biochem Funct 2008; 26;: 664–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mohammadi R, Azizi S, Delirezh N, et al. Comparison of beneficial effects of undifferentiated cultured bone marrow stromal cells and omental adipose-derived nucleated cell fractions on sciatic nerve regeneration. Muscle Nerve 2011; 43: 157–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pachon-Pena G, Yu G, Tucker A, et al. Stromal stem cells from adipose tissue and bone marrow of age-matched female donors display distinct immunophenotypic profiles. J Cell Physiol 2011; 226: 843–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Martin DR, Cox NR, Hathcock TL, et al. Isolation and characterization of multipotential mesenchymal stem cells from feline bone marrow. Exp Hematol 2002; 30: 879–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jin GZ, Yin XJ, Yu XF, et al. Generation of neuronal-like cells from umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells of a RFP-transgenic cloned cat. J Vet Med Sci 2008; 70: 723–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jin GZ, Yin XJ, Yu XF, et al. Enhanced tyrosine hydroxylase expression in PC12 cells co-cultured with feline mesenchymal stem cells. J Vet Sci 2007; 8: 377–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kubo H, Berretta RM, Jaleel N, et al. c-Kit+ bone marrow stem cells differentiate into functional cardiac myocytes. Clin Transl Sci 2009; 2: 26–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Quimby JM, Webb TL, Gibbons DS, et al. Evaluation of intrarenal mesenchymal stem cell injection for treatment of chronic kidney disease in cats: a pilot study. J Feline Med Surg 2011; 13: 418–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bunnell BA, Flaat M, Gagliardi C, et al. Adipose-derived stem cells: isolation, expansion and differentiation. Methods 2008; 45: 115–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Avery PR, Lehman TL, Hoover EA, et al. Sustained generation of tissue dendritic cells from cats using organ stromal cell cultures. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 2007; 117: 222–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: Application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J Immunol Methods 1983; 65: 55–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Verfaillie CM. Adult stem cells: assessing the case for pluripotency. Trends Cell Biol 2002; 12: 502–08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Vidal MA, Walker NJ, Napoli E, et al. Evaluation of senescence in mesenchymal stem cells isolated from equine bone marrow, adipose tissue, and umbilical cord tissue. Stem Cells Dev 2011; [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Schaffler A, Buchler C. Concise review: adipose tissue-derived stromal cells — basic and clinical implications for novel cell-based therapies. Stem Cells 2007; 25: 818–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Martinello T, Bronzini I, Maccatrozzo L, et al. Canine adipose-derived-mesenchymal stem cells do not lose stem features after a long-term cryopreservation. Res Vet Sci 2011; 91: 18–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Vieira NM, Brandalise V, Zucconi E, et al. Isolation, characterization, and differentiation potential of canine adipose-derived stem cells. Cell Transplant 2010; 19: 279–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wagner W, Wein F, Seckinger A, et al. Comparative characteristics of mesenchymal stem cells from human bone marrow, adipose tissue, and umbilical cord blood. Exp Hematol 2005; 33: 1402–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zuk PA, Zhu M, Ashjian P, et al. Human adipose tissue is a source of multipotent stem cells. Mol Biol Cell 2002; 13: 4279–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pittenger MF, Mackay AM, Beck SC, et al. Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science 1999; 284: 143–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Di Nicola M, Carlo-Stella C, Magni M, et al. Human bone marrow stromal cells suppress T-lymphocyte proliferation induced by cellular or nonspecific mitogenic stimuli. Blood 2002; 99: 3838–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]