Abstract

Two groups of feline panleukopenia (FPV), feline calicivirus (FCV) and feline herpesvirus 1 (FHV-1) seronegative kittens (six cats per group) were administered one of two feline viral rhinotracheitis, calcivirus and panleukopenia (FVRCP) vaccines subcutaneously (one inactivated and one modified live) and the serological responses to each agent were followed over 49 days (days 0, 2, 5, 7, 10, 14, 21, 28, 35, 42, 49). While the kittens administered the modified live FPV vaccine were more likely to seroconvert on day 7 after the first inoculation than kittens administered the inactivated vaccine, all kittens had seroconverted by day 14. In contrast, FHV-1 serological responses were more rapid following administration of the inactivated FVRCP vaccine when compared with the modified live FVRCP vaccine. There were no statistical differences between the serological response rates between the two FVRCP vaccines in regard to FCV.

Short Communication

Feline panleukopenia virus (FPV), feline calicivirus (FCV) and feline herpesvirus 1 (FHV-1) infections in cats are very common and can cause significant morbidity and mortality in cats without specific immunity. Cats in crowded environments such as humane societies, pet stores and animal shelters are commonly infected and can become ill because of high risk of exposure, stress and potential for co-infections.1–3 Vaccines containing FPV, FCV and FHV-1 are considered ‘core’ by the American Association of Feline Practitioners (AAFP) and the sooner immunity can be stimulated the less likely severe illness will result if the cat is exposed to a pathogenic field strain. 4

Serum antibody responses to FPV, FCV and FHV-1 can be easily measured and can be used to predict resistance to infection (FPV) or disease (FCV, FHV-1) on challenge.5,6 However, very little temporal information is available to document when protective antibody levels develop in normal kittens administered commercially-available products. In one study, one dose of either a modified live feline viral rhinotracheitis, calcivirus and panleukopenia (FVRCP) vaccine for intranasal administration (UltraNasal FVRCP; HESKA Corporation, Loveland, CO, USA) or a modified live FVRCP vaccine for subcutaneous administration (Purevax Feline 3; Merial, Duluth, GA, USA) were given to adult seronegative cats (five cats per group) and the serological responses of FPV, FCV and FHV-1 to each agent were followed over 28 days. 7 For FPV and FHV-1, there were no differences in seroconversion rates between the two groups of cats on any day tested after inoculation. For FCV, the cats that were administered the intranasal FVRCP vaccine were more likely to seroconvert on day 10 and on day 14 when compared with cats who were administered the FVRCP vaccine subcutaneously. There is only one inactivated FVRCP vaccine available for subcutaneous administration to cats in the USA (Fel-O-Vax PCT; Boehringer-Ingelheim Vetmedica, St Joseph, MO, USA). When administered once to feral cats during a trap-neuter-return program, cats administered this vaccine had the same proportion of protective FPV, FHV-1 or FCV antibody titers when compared with cats administered a modified live FVRCP vaccine. 8 Whether the temporal appearance of FPV, FCV and FHV-1 antibodies in the serum of vaccinated kittens after administration of the inactivated FVRCP vaccine is similar to those induced by modified live vaccines is unknown. The purpose of this study was to determine when seroconversion occurs in seronegative cats after administration of three doses of a commercially-available inactivated live FVRCP vaccine administered subcutaneously or a commercially-available modified live FVRCP vaccine administered subcutaneously.

The experimental design of this study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Colorado State University. Specific pathogen-free kittens (n = 12) born to FHV-1, FCV and FPV seronegative, unvaccinated queens were tested for FHV-1 (serum neutralization), FCV (serum neutralization) and FPV antibodies (hemagglutination inhibition) at 6 weeks of age using commercially-available assays (New York State Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory, Ithaca, NY, USA). All kittens were negative for antibodies against the three agents and were shipped to Colorado State University at 8 weeks of age. At approximately 9 weeks of age, the kittens were divided into two groups of six kittens, housed in separate rooms and inoculated subcutaneously by group with the inactivated FVRCP vaccine (Fel-O-Vax PCT; Boehringer-Ingleheim Vetmedica) or the modified live vaccine (Fel-O-Guard Plus 3; Boehringer-Ingleheim Vetmedica) on day 0, day 14 and day 28, as recommended in the AAFP vaccine guidelines for cats housed in high-risk environments. 4 Blood (1 ml) was collected on days 0, 2, 5, 7, 10, 14, 21, 28, 35, 42, 49 after the first inoculation. On vaccination days, blood was collected prior to vaccine administration. Antibodies against FPV, FCV and FHV-1 in serum were measured as described on all sample dates (New York State Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory). The reference laboratory considered the titers predicting resistance to be > 10, > 4 and > 4 for FPV, FCV and FHV-1, respectively. To determine whether differences in vaccine response occurred between groups, the number of cats with titers greater than the cut-off on each sample date were compared by Fisher’s exact test with significance defined as P <0.05.

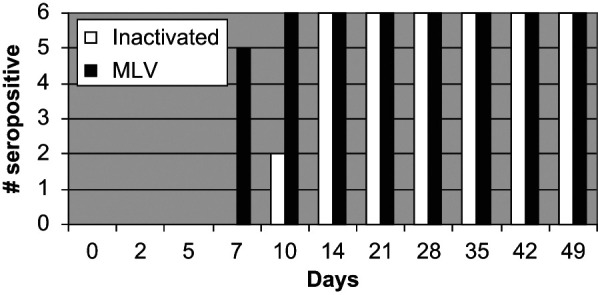

All cats in both groups had FPV titers above the positive cut-off by day 14 after the first inoculation and these titers were maintained for the duration of the study (Figure 1). On day 7, none of the six cats administered the inactivated FVRCP vaccine and five of the six cats administered the modified live FVRCP vaccine were positive; these results were significantly different (P = 0.015). On day 10, two out of six cats administered the inactivated FVRCP vaccine and six out of six cats administered the modified live FVRCP vaccine were positive, but the results were not significantly different. In the inactivated FVRCP group, the maximal FPV titer was reached on day 21 (five cats) or day 28 (one cat). In the modified live FVRCP group, the maximal FPV titer was reached on day 7 (two cats), day 21 (two cats) and day 28 (two cats). Maximal FPV titers in the inactivated FVRCP group ranged from 640–2560 and maximal FPV titers in the modified FVRCP group ranged from 2560–5120.

Figure 1.

Serum FPV antibody responses in kittens administered either an inactivated FVRCP vaccine subcutaneously or a modified live FVRCP vaccine subcutaneously on days 0, 14 and 28

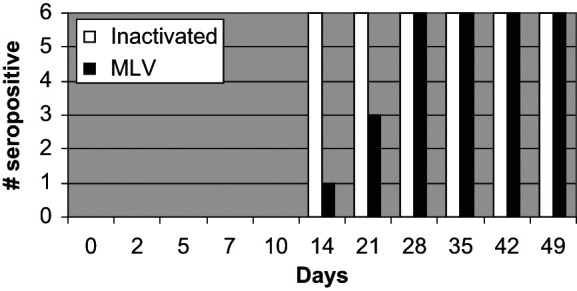

All cats in both groups had FHV-1 titers above the positive cut-off by day 28 after the second inoculation (Figure 2). On day 14, six out of six cats administered the inactivated FVRCP vaccine and one of six cats administered the modified live FVRCP vaccine were positive; these results were significantly different (P = 0.015). On day 21, six out of six cats administered the inactivated FVRCP vaccine and three out of six cats administered the modified live FVRCP vaccine were positive, but the results were not significantly different. In the inactivated FVRCP group, the maximal FHV-1 titer was reached on day 35 (four cats) or day 42 (two cats). In the modified live FVRCP group, the maximal FHV-1 titer was reached on day 28 (four cats) or day 35 (two cats). Maximal FHV-1 titers in the inactivated FVRCP group ranged from 6–384 and maximal FHV-1 titers in the modified FVRCP group ranged from 24–192.

Figure 2.

Serum FHV-1 antibody responses in kittens administered either an inactivated FVRCP vaccine subcutaneously or a modified live FVRCP vaccine subcutaneously on days 0, 14 and 28

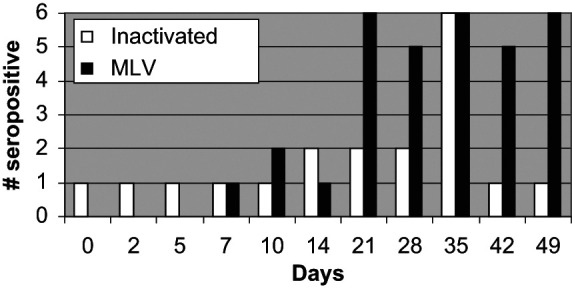

All cats in both groups had FCV titers above the positive cut-off by day 35 (Figure 3). On day 42 and day 49, only one cat administered the inactivated FVRCP vaccine was above the cut-off. On day 42, one cat administered the modified live FVRCP vaccine was below the cut-off but was above the cut-off again on day 49. In the inactivated FVRCP group, the maximal FCV titer was reached on day 28 (two cats) or day 35 (four cats). In the modified live FVRCP group, the maximal FCV titer was reached on day 21 (two cats), day 28 (two cats), day 35 (one cat) and day 42 (one cat). Maximal FCV titers in the inactivated FVRCP group ranged from 6–48 and maximal FCV titers in the modified FVRCP group ranged from 32–256.

Figure 3.

Serum FCV antibody responses in kittens administered either an inactivated FVRCP vaccine subcutaneously or a modified live FVRCP vaccine subcutaneously on days 0, 14 and 28

These kittens were born to seronegative queens in a barrier facility and so the potential for maternal antibodies to influence the results should be non-existent. While this experiment allowed for defining what would happen to FPV, FHV-1 and FCV naïve research kittens after administration of these two vaccines, it may not accurately reflect the responses that would be seen in client-owned cats of the same age in the field. In that situation, it is likely that at least some kittens at 9 weeks of age would still have maternal antibodies against the antigens which could affect the response to vaccination. Further information concerning seroconversion rates in kittens with varying levels of maternal antibodies should be gathered in future studies.

Assuming the serological cut-offs are accurate for prediction of resistance on challenge, both vaccines ultimately induced protective titers in all kittens after vaccination. However, the response times varied by vaccine and by antigen—these variations are discussed in the sections that follow. In addition, because the cats were not tested daily, the minimal time to seroconversion for each individual antigen and cat is unknown. Regardless of serological test results, challenge inoculations are required to more definitely define when protection first occurs. In kittens without maternal antibodies, previous studies have shown on challenge that protective immunity can develop very quickly. For example, kittens vaccinated with a FVRCP vaccine for intranasal administration were significantly less ill than controls when challenged with a virulent strain of FHV-1 as soon as 4 days after one inoculation. 9 In another study, cats vaccinated subcutaneously with modified live FPV, modified live FHV-1 and inactivated FCV had similar levels of protection on challenge at either 1 or 3–4 weeks after vaccination. 10 These results suggest that protection is imparted very soon after vaccine administration.

In the study described here, administration of the modified live FPV-containing vaccine resulted in earlier seroconversion than the inactivated FPV containing vaccine but all cats in both vaccine groups had protective titers by day 14 after one inoculation. As serum antibody responses play a large role in protection against FPV, these results suggest that the modified live product could induce protection several days earlier than the inactivated product in some kittens. However, the group results were only statistically different on day 7. These results support the AAFP recommendations that modified live FPV vaccines be used during the primary immunization period in kittens at high risk of exposure to panleukopenia virus, but either vaccine may be appropriate for kittens seen in general practices with low risk of exposure. 4 However, a challenge study is needed to determine whether the differences noted between the two groups of cats on day 7 were truly clinically significant.

Administration of the inactivated FHV-1 containing vaccine resulted in earlier seroconversion than the modified live FHV-1 containing vaccine in the study described here. These results are similar to those reported in another study where a modified live FHV-1 vaccine induced seroconversion either after one or two doses of the vaccine. 10 In a different study, another modified live FHV-1 vaccine administered subcutaneously failed to induce seroconversion in any of five healthy, FHV-1 seronegative, adult cats after administration of a single dose. 9 However, as cell-mediated immune responses play a large role in protection against FHV-1, these results may or may not be clinically significant.

In the study described here, more cats administered the modified live FCV containing vaccine had titers above the cut-off on days 21 and 28 than the cats administered the inactivated FCV containing vaccine but the results were not statistically different. All of the cats administered the inactivated FCV containing vaccine seroconverted by day 35 after the third vaccine administration. These results were similar to another study of an inactivated FCV-containing vaccine where FCV seroconversion was not noted until day 56, which was 28 days after the second dose of vaccine was administered. As discussed for FHV-1, cell-mediated immune responses play a large role in protection against FCV and so these results may or may not be clinically significant. There are multiple FCV strains with antigenic diversity. Based on serum neutralization assay results, administration of vaccines containing two or more FCV strains results in a wider range of cross protection than administration of vaccines containing one FCV strain.11–13

Funding

This project was funded by Fort Dodge Animal Health and performed by staff members of the Center for Companion Animal Studies at Colorado State University.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- 1. Hurley KE, Pesavento PA, Pedersen NC, et al. An outbreak of virulent systemic feline calicivirus disease. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2004; 224: 241–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pedersen NC, Sato R, Foley JE, Poland AM. Common virus infections in cats, before and after being placed in shelters, with emphasis on feline enteric coronavirus. J Feline Med Surg 2004; 6: 83–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Veir JK, Ruch-Gallie R, Spindel ME, Lappin MR. Prevalence of selected infectious organisms and comparison of two anatomic sampling sites in shelter cats with upper respiratory tract disease. J Feline Med Surgery 2008; 10: 551–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Richards JR, Elston TH, Ford RB, et al. The 2006 American Association of Feline Practitioners Feline Vaccine Advisory Panel report. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2006; 229: 1405–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lappin MR, Andrews J, Simpson D, Jensen WA. Use of serologic tests to predict resistance to feline herpesvirus 1, feline calicivirus, and feline parvovirus infection in cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2002; 220: 38–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Scott FW, Geissinger CM. Long-term immunity in cats vaccinated with an inactivated trivalent vaccine. Am J Vet Res 1999; 60: 652–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lappin MR, Veir J, Hawley J. Feline panleukopenia virus, feline herpesvirus-1, and feline calicivirus antibody responses in seronegative specific pathogen-free cats after a single administration of two different modified live FVRCP vaccines. J Feline Med Surg 2009; 11: 159–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fischer SM, Quest CM, Dubovi EJ, et al. Response of feral cats to vaccination at the time of neutering. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2007; 230: 52–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lappin MR, Sebring RW, Porter M, et al. Effects of a single dose of an intranasal feline herpesvirus 1, calicivirus, and panleukopenia vaccine on clinical signs and virus shedding after challenge with virulent feline herpesvirus 1. J Feline Med Surg 2006; 8: 158–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jas D, Aeberlé C, Lacombe V, et al. Onset of immunity in kittens after vaccination with a non-adjuvanted vaccine against feline panleucopenia, feline calicivirus and feline herpesvirus. Veterinary J 2009; 182: 86–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Masubuchi K, Wakatsuki A, Iwamoto K, et al. Immunological and genetic characterization of feline caliciviruses used in the development of a new trivalent inactivated vaccine in Japan. J Vet Med Sci 2010; 72: 1189–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Porter CJ, Radford AD, Gaskell RM, et al. Comparison of the ability of feline calicivirus (FCV) vaccines to neutralise a panel of current UK FCV isolates. J Feline Med Surg 2008; 10: 32–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Huang C, Hess J, Gill M, Hustead D. A dual-strain feline calicivirus vaccine stimulates broader cross-neutralization antibodies than a single-strain vaccine and lessens clinical signs in vaccinated cats when challenged with a homologous feline calicivirus strain associated with virulent systemic disease. J Feline Med Surg 2010; 12: 129–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]