Abstract

A radiographical study of a cat mummy from the Egyptian collection of the National Archeological Museum in Parma, Italy was carried out in order to evaluate the content and to describe how cats were wrapped and mummified. The mummy contained the complete skeleton of a 4–5-month-old cat. Radiology revealed the position of the cat’s body; it was wrapped to occupy the smallest space possible. In order to better position the cat, the ribs of the thorax were compressed cranio-caudally and the fore limbs were then positioned very close to the thorax. The hind limbs were flexed close to the lumbar spine and the tibio-tarsal joints were subluxated to allow the repositioning of the tarsal, metatarsal and phalanx bones cranio-caudally near the tibiae. A coccygeal vertebra was fractured in order to reposition the tail as close as possible to the body. Atlanto-occipital subluxation and a fracture/hole was present in the occipital region of the skull: whether this was made for draining skull contents as a mummification process and/or to euthanase the cat remains open for discussion.

Short Communication

Radiology has frequently been used by archeologists to study ancient specimens, including buried or mummified human and animal bodies from Ancient Egypt. 1 The mummy of a cat, which is part of the Egyptian collection of the National Archaeological Museum in Parma, Italy, was examined radiographically in order to evaluate the content and to describe how cats were wrapped and mummified in ancient Egypt. The mummy was bought in the 19th century, along with most of the other artefacts in the museum’s Egyptian collection.

In ancient Egypt, mummification was carried out on humans and many animals, including cats. It is known that from 1350 BC, cats were occasionally buried with their owners. Later, however, during the XXII Dynasty (945–715 BC), as a consequence of a change in Egyptian religious beliefs, many animals were thought to be the embodiment of gods and goddesses. Female cats were believed to represent the goddess Bastet. Consequently, temples devoted to Bastet were constructed throughout Egypt, such as the temple found in the Ancient Egyptian city Bubastis located along the Nile River in the Delta region of Lower Egypt. When cats died, they were mummified and buried in communal graves in the temple.

From about 332 BC to 30 BC, animals began to be raised near the temples for the specific purpose of being mummified. People bought the mummies and left them at the temple as offerings. For this reason, many cats that had died prematurely and by unnatural deaths have been found. Kittens, aged 2–4 months old, were sacrificed in huge numbers, because they were more suitable for mummification. This is likely the case of the cat mummy from the museum in Parma. Indeed, the abnormal findings in the caudal portion of the calvarium may suggest an unnatural death. Cat mummies were so numerous that in the late 19th century, mummified cats were shipped from the town of Beni Hasan, in middle Egypt, to the English port of Liverpool to be pulverised and sold as fertiliser in England.

Owing to the increasing demand for mummified cats by the Egyptian people, different ‘types’ of cat mummies were sold with different features according to the client’s requests. It was possible to find ‘cheap’ cat mummies with just a few bones inside up to a complete mummified cat body embedded in decorated wrappings. As far as the cat mummy from the museum of Parma is concerned, the arrangement of the mummy’s wrappings is intricate, with various geometrical patterns. The eyes are depicted in black ink on small round pieces of linen bandage. The cat skeleton is also complete, meaning that it is one of the most valuable types.

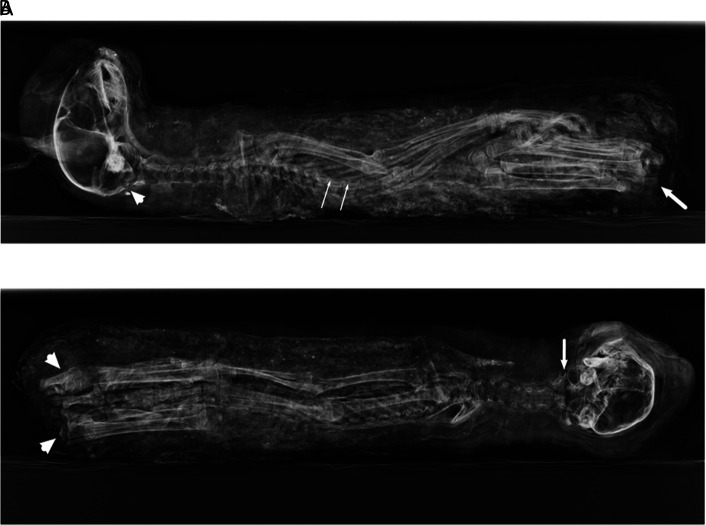

Figure 1.

Latero-lateral (A) and ventrodorsal (B) projections of the cat mummy. Within the elongated oval shape of the cat mummy, the squeezed skeletal body of the cat embedded in radiopaque wrappings is visible. (A) The thin white arrows indicate the squeezed thorax; white arrow, fractured vertebra of the tail; white arrowhead, fracture/hole in the occipital region of the skull. (B) White arrowheads indicate the luxated tibio-tarsal joints; white arrow atlanto-occipital subluxation

The cat skeleton shows open physes of long bones and vertebrae and the eruption of definitive canine teeth suggest a cat ranging in age from 4–5 months. Radiology showed the position of the body, which was wrapped so as to occupy the smallest space possible. In order to better position the cat, the ribs of the thorax were compressed cranio-caudally and the fore limbs were then positioned very close to the thorax. Regarding the folded chest shape, it is not clear if this condition was caused by the mummification process where cats were eviserated in the same way as human mummies. Most possibly, the animal was treated with a chemical substance called natron, a naturally occurring mixture of sodium carbonate decahydrate, sodium bicarbonate with small quantities of salt and sodium sulphate, and particular herbs to improve artificial dehydration, and then positioned in a sort of sitting position, before bandaging was performed. The ‘sitting position’ with flexed hind limbs and extended fore limbs against the thorax, reduces the mummy’s dimensions to a minimum. Furthermore, the cat as a divinity has always been represented in a ‘sitting position’, as it is also shown in hieroglyphic inscriptions from over 4000 years ago. It is likely that the folded chest was simply caused by the compressive bandages.

The hind limbs were flexed close to the lumbar spine and the tibio-tarsal joints were subluxated to allow the repositioning of the tarsal, metatarsal and phalanx bones cranio-caudally near the tibiae. A coccygeal vertebra was fractured in order to reposition the tail as close as possible to the body. Atlanto-occipital subluxation and a fracture/hole were present in the occipital region of the skull: whether this was made for draining skull contents as a mummification process and/or to euthanase the cat remains open for discussion.

This cat mummy has to be considered a high-quality archeological finding because of the complete body observed radiographically (and not just of a part of the animal) and the intricate wrappings with various geometrical patterns and depicted eyes.

The fact that the cat was young suggests that it was one of those bred specifically for mummification. It can be almost certainly excluded that this mummy was buried with its owner. It is more likely that it was an offering to the goddess Bastet. This was a popular tradition from late 332 BC to the 32 BC, when large numbers of these mummies were produced and sold to those who venerated the goddess Bastet.

The National Museum of Parma bought this mummy in the 18th century from an antiquarian; there is no documentation about which part of the Egypt it came from, but it is certain that it was an offering to the goddess Bastet, possibly from the temple of Bubastis.

In conclusion, the present radiographic study of the cat mummy is of great importance, showing it to be a high quality archeological finding.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Reference

- 1. Armitage PL, Clutton-Brock J. A radiological and histological investigation into the mummification of cats from Ancient Egypt. J Archael Sci 1981; 8: 185–96. [Google Scholar]