Abstract

The life expectancy of domestic pet cats is increasing, along with the occurrence of geriatric-onset behavioural problems, such as cognitive dysfunction syndrome (CDS). While the cause of CDS is unclear, it has been suggested that it may result from age-related neurodegeneration. In aged and in particular senile human beings, histopathological changes may include the extracellular accumulation of plaque-like deposits of β-amyloid (Aβ) protein and the intracellular accumulation of an abnormally hyperphosphorylated form of the microtubule-associated protein, tau. In severe cases, the latter may form into neurofibrillary tangles. Brain material was assessed from 19 cats, aged from 16 weeks to 14 years; 17 of which had clinical signs of neurological dysfunction. Immunohistochemical methods were used to detect Aβ and its intracellular precursor protein (amyloid precursor protein (APP)) and hyperphosphorylated-tau.

APP was constitutively expressed, with diffuse staining of neurons and blood vessels being detected in all cats. More intense staining and diffuse extracellular Aβ staining deposits were found within the deep cortical areas of the anterior- and occasionally mid-cerebrum of seven cats, all of which were over 10 years of age. Neurons staining intensely positive for AT8-immunoreactivity were seen in two cats, aged 11 and 13 years. However, no mature neurofibrillary tangles were detected. This study demonstrated that extracellular Aβ accumulation and AT8-immunoreactivity within neurons are age-related phenomena in cats, and that they can occur concurrently. There are similarities between these changes and those observed in the brains of aged people and other old mammals.

With improvements in nutrition and veterinary care, the life expectancy of pet cats and dogs is increasing (Broussard et al 1995, Morgan 2002). Accompanying this growing geriatric population, an increasing number of animals have signs of behavioural dysfunction that cannot be linked to systemic disease (Chapman and Voith 1990, Ruehl et al 1995). It is generally accepted that cognitive and motor performance deteriorates with age, and experiments with cats have indicated that this usually occurs between 10 and 20 years of age (Harrison and Buchwald 1982, 1983, Levine et al 1987). Recent clinical studies suggest that 28% of domestic pet cats aged 11–14 years develop at least one geriatric-onset behaviour problem, and this increases to over 50% for cats of 15 years of age or older (Moffat and Landsberg 2003).

In human beings, there is a range of histopathological change associated with increasing degrees of cognitive dysfunction; from mild early ageing changes, through significant neurodegenerative pathology to, for example, Alzheimer's disease (AD). Understandably, there is most known about the changes that occur in AD. Histopathologically, this is typified by the presence of senile plaques (SP) and neurofibrillary tangles (reviewed in Selkoe 1997 and Mattson 2004). Senile plaques are formed by the extracellular accumulation of β-amyloid (Aβ) protein that is formed from its constitutively produced intracellular precursor, amyloid precursor protein (APP). Neurofibrillary tangles (NFT) are formed by the initially intracellular accumulation of an abnormally hyperphosphorylated form of the microtubule-associated protein tau (Goedert 1993, Trojanowski et al 1993; reviewed in Selkoe 1997 and Mattson 2004). While there are a number of theories suggesting how these deposits may be associated with neurological degeneration, it is currently believed that the accumulation of Aβ into SP may initiate inflammatory change and neurotoxicity which ultimately results in tau hyperphosphorylation, NFT formation and neurological dysfunction (Hardy and Higgins 1992, Dickson et al 1995; reviewed in Selkoe 1997 and Mattson 2004). In addition to accumulating as SP, Aβ also accumulates around the meninges and blood vessels (eventually resulting in cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA)) (Selkoe et al 1987, Selkoe 1997).

While these changes may be associated with AD they are not specific to that disorder. In human beings, SP and CAA are also seen in the brains of many elderly people who did not have clinical signs of dementia (Selkoe et al 1987), and similar but less pronounced SP and CAA have been seen in the brains of other aged mammals, including dogs, sheep, goat, bear and wolverine (Head et al 2001). In addition, hyperphosphorylated tau is not only associated with age-related neurodegeneration, it is also present during normal early postnatal development (Riederer et al 2001), and arises in response to degenerative events such as ischaemia or seizures (Burkhart et al 1998, Blumcke et al 1999).

Initially, reports of SP in dogs were controversial because they are not easily detected using standard silver stains or thioflavine-S fluorescence. However, modified pre-treatment protocols and more sensitive immunohistochemical techniques have resulted in better characterisation of these plaques (Cummings et al 1993, 1996a, Kuroki et al 1997, Satou et al 1997, Head et al 2000, 2001, Head 2001). It is now known that the pattern of canine Aβ accumulation parallels that seen in people, being age related, with plaques developing in several cortical and subcortical brain regions (Cummings et al 1996b, Satou et al 1997, Head et al 1998, 2000, 2001, Head 2001, Kuroki et al 1997).

Several studies have shown a correlation between the extent and location of Aβ deposition and the severity and type of neuronal dysfunction in dogs (Cummings et al 1996b, Kuroki et al 1997, Head et al 1998, 2000, 2001, Head 2001). However, while all dogs naturally accumulate diffuse SP and CAA with age, some individuals and certain breeds appear to develop them at an earlier age (Bobik et al 1994, Milgram et al 1994, Head et al 2000; reviewed in Head et al 2001). These findings are similar to those seen in human beings, where genetics, diet and life-style choices have all been found to influence the prevalence and pattern of senility (reviewed in Selkoe 1997 and Mattson 2004).

The understanding of neurodegeneration in cats is less advanced than in dogs, and there have been few studies into the neuropathology of ageing in this species. Visualisation of Aβ in the cat brain, as for the dog, is dependent upon the technique used. A recent survey of pathological findings in the brains of 286 cats with nervous disorders failed to find any evidence of amyloid deposition on routine haematoxylin and eosin sections (Bradshaw et al 2004) and, when using silver stains, SP have only been found in cats older than 18 years of age (Braak et al 1994, Nakamura et al 1996, Kuroki et al 1997). More sensitive immunohistochemical techniques have identified diffuse extracellular Aβ staining deposits, consistent with SP, in a small number of cats (Cummings et al 1996b, Nakamura et al 1996, Kuroki et al 1997, Head et al 2001, 2005, Georgia et al 2004). In these reports a total of 25 cats were studied using this more sensitive methodology; 23 were over 12 years of age, and two were under 4 years of age (Cummings et al 1996b; Nakamura et al 1996, Kuroki et al 1997, Head et al 2001, 2005). While these studies do appear to show that older cats are more likely to develop extracellular Aβ deposits (only the 14 oldest cats, all of which were over 16 years of age, were found to have them) the small number warrants careful interpretation. Currently, it is therefore still to be confirmed whether these deposits are truly age related, and there is no information on the prevalence of these deposits within cat brains, the locations in which they are most likely to occur, whether they are breed related, and whether they correlate with cognitive dysfunction. In addition, the extracellular Aβ deposits in cats appear to be even more diffuse than the SP seen in dogs, and quite unlike the well developed and circumscribed SP that are typical of human beings (Cummings et al 1996b, Head et al 2001, 2005). It is for this reason that the term extracellular Aβ deposits rather than SP will be used in this report.

The aim of this study was to identify potential Aβ accumulation and hyperphosphorylated tau deposition in the brain of domestic cats, to determine which regions of the brain are most typically affected, and to look for potential associations with age and, possibly, clinical presentation.

Materials and Methods

Brains from 19 cats were investigated (Table 1). These were obtained from clinical cases that had undergone routine post mortem examination at the Comparative Pathology Laboratory, University of Bristol, between 1975 and 2002. In order to assess age-related changes a wide age range of cats were selected from 16 weeks to 14 years of age. To enhance the chance of detecting neurodegenerative change 17 of the cats were selected because they had shown clinical signs of neurological dysfunction, and in 16 of these cases no abnormalities had been detected on routine histopathological examination. One cat (cat 12) was found to have changes suggestive of Aβ deposition. Unfortunately, the retrospective nature of the study and the age of the archive material meant that all of the cases had not been investigated consistently. Where clinical details were available the cats had been shown to be negative for feline leukaemia virus and feline immunodeficiency virus infections, and to be unremarkable on routine serum biochemical analysis. The bodies had been submitted for post mortem examination with no obvious final diagnosis being evident. Two cats (cats 1 and 2) were included because they were considered unlikely to show neurodegenerative change; they had shown no clinical signs of behavioural or neurological dysfunction, and changes were not observed in their brains on histopathological examination. For histopathological examination brains were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, and processed to paraffin wax. Sections were routinely stained with haematoxylin and eosin. Further sections from cat 12 were also stained with Congo red.

Table 1.

Clinical details of the cats in the study

| Cat number | Age | Sex | Breed | Clinical signs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2–4 y | MN | DSH | None – killed in a road accident; non-neurological control |

| 2 | 6 y | M | DSH | Lame on right fore, dyspnoea, ruptured diaphragm; non-neurological control |

| 3 | 16 w | F | Oriental | One of three kittens with neurological signs noticed from 4 weeks of age; showing disorientation and incoordination |

| 4 | 16 w | M | DSH | Acute neurological signs with plantigrade hind limb gait, mild proprioceptive deficits, intention tremor and hyperaesthesia |

| 5 | 1.5 y | F | Birman | Acute neurological signs with circling and blindness; also found to have pyothorax |

| 6 | 2 y | MN | DSH | Neurological signs with a stiff gait all of its life, now generalised tremors, hyper-reflexia, ataxia and reduced menace reflex |

| 7 | 2 y | F | DSH | Acute neurological signs with quadriplegia and proprioceptive deficits in all limbs but patellar reflexes normal |

| 8 | 3 y | FN | Burmese | Chronic progressive neurological signs with ataxia and hind limb hypermetria |

| 9 | 4 y | M | DSH | Neurological signs, ataxia, head tremor and hyperaesthesia |

| 10 | 7 y | FN | DSH | Chronic progressive behavioural change with hyperaesthesia and aggression |

| 11 | 10 y | MN | DSH | Six weeks of neurological signs with ataxia and disorientation |

| 12 | 10 y | MN | DSH | Two weeks of behavioural change with seizures, vocalisation, hypersalivation, facial twitching and hyperaesthesia |

| 13 | 10 y | M | DSH | Chronic behavioural change with ataxia and aggression |

| 14 | 11 y | MN | DSH | Chronic neurological signs with seizures |

| 15 | 13 y | FN | DLH | Three weeks of progressive neurological signs with seizures and depression |

| 16 | 14 y | MN | DSH | Chronic neurological signs with stiffness, reluctance to move, and shifting lameness |

| 17 | 14 y | FN | Siamese | Chronic progressive neurological signs with seizures and multiple deficits |

| 18 | 14 y | MN | DSH | Behavioural changes and apparent blindness |

| 19 | 14 y | M | DSH | Acute onset of seizures |

y=year; w=weeks; DSH=domestic shorthair; DLH=domestic longhair; M=male; F=female; N=neutered.

For immunohistochemical staining, 10 μm sections were mounted on organosilane-coated slides. Sections from the anterior cerebrum, mid-cerebrum, rostral pons, cerebellum with medulla at the level of the vestibular nuclei, medulla at the level of the obex, and/or the spinal cord, were examined, as available. Sections were pre-treated with 90% formic acid for 4 min (Kitamoto et al 1987), followed by incubation in 3% hydrogen peroxide and 3% methanol for 30 min. The primary antibodies were incubated with the tissue overnight (diluted in 0.1 M Tris, 0.85% saline, pH 7.4–7.6, 0.1% Triton X-100, 2.0% bovine serum albumin) at room temperature. Two mouse monoclonal antibodies were used as the primary antibodies: antibody to human Aβ protein, which also binds to its precursor protein, human APP (4G8; Signet Labs, MA, USA), diluted 1:1500, and antibody to hyperphosphorylated tau protein (AT8; Endogen, MA, USA), diluted 1:500, both of which have been described elsewhere (Head et al 2005). Bound antibody was detected using a biotinylated anti-rabbit/mouse ABC peroxidase kit (Vector Laboratories, CA, USA), and visualised using brown DAB (Vector Laboratories, CA, USA). For controls the primary or secondary antibodies were omitted. All sections were examined using light microscopy. Control sections using no primary antibody were negative.

Results

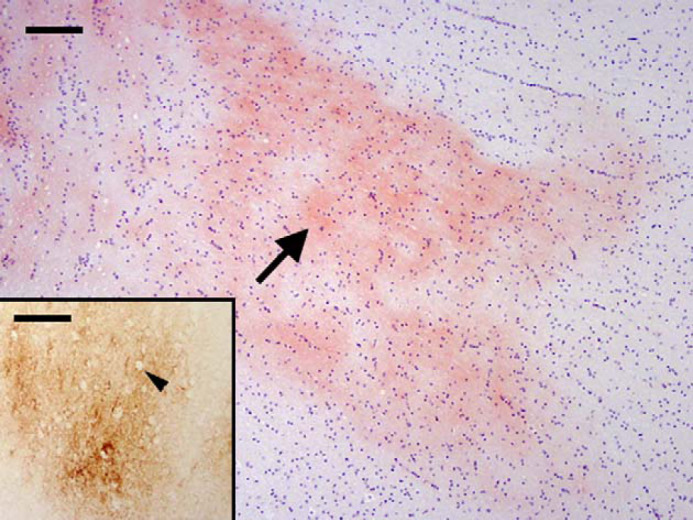

On histopathological examination, the brain of cat 12 was found to have a few, small, eosinophilic foci in the deep layers of the grey matter, close to the white matter, adjacent to the hippocampus. Congo red staining confirmed the presence of a few diffuse, finely granular, variable sized foci (Fig 1), with fine, apple green birefringence under polarised light.

Fig 1.

Cat 12, brain, frontal cortex. Diffuse amyloid deposition (arrow) within the neuropil of the deep cortical tissue adjacent to the hippocampus. Congo red. Bar, 100 μm. Inset: Diffuse and coalescing granular foci of extracellular β-amyloid (Aβ) deposits within the neuropil of the deep cortical tissue. Arrow head shows a hole in the deposit where an intact non-staining neuron is present. Immunostain, antibody to human Aβ protein and its precursor, amyloid precursor protein (APP) (4G8). Bar, 100 μm.

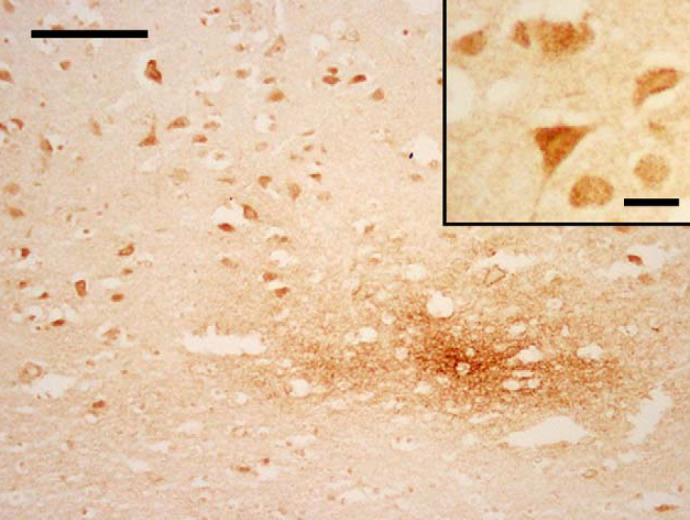

Using the antibody to APP and Aβ (4G8), intracellular staining of neurons (Fig 2) and blood vessels was observed in all cats (Table 2). There was variation between cats, from mild to intense staining, with the neurons of older cats tending to stain more intensely with a clearly punctate and intracellular pattern (Table 2). In addition, diffusely staining extracellular Aβ deposits were found within the deep layers of the cerebral cortex (Figs 1 and 2) of seven cats (Table 2), all of which were over 10 years of age. The most intense staining was typically seen in the frontal cortex, where it stained neurons within the grey matter and was seen as diffuse and coalescing granular foci (extracellular Aβ deposits) within the neuropil of the deep cortical tissue adjacent to the white matter. Some positively stained neurons, blood vessels and extracellular Aβ deposits were also seen in other areas of the cerebral cortex, and individual neurons were stained within the medulla, pons, cerebellum, and spinal cord.

Fig 2.

Cat 13, brain, frontal cortex. Intense staining of neurons and diffuse granular focus of extracellular Aβ deposits within the neuropil of the deep cortex. Immunostain, 4G8. Bar, 100 μm. Inset: higher magnification of neurons, where the stain is punctate and intracellular. Bar, 25 μm.

Table 2.

4G8 and AT8-immunoreactivity of cat brains

| Cat number | Sites examined | 4G8* positive neurons | 4G8 positive blood vessels | Large extracellular 4G8 positive deposits in deep cortex | AT8Ψ positive neurons |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ant cerebrum, cerebellum, spinal cord | + | + | − | − |

| 2 | Mid-cerebrum | + | + | − | − |

| 3 | Ant cerebrum, cerebellum | ± | ± | − | − |

| Pons | + | + | − | − | |

| 4 | Mid-cerebrum | + | + | − | − |

| 5 | Ant And hind cerebrum, cerebellum | + | + | − | − |

| 6 | Mid-cerebrum, cerebellum | + | + | − | − |

| 7 | Ant cerebrum, pons, cerebellum | + | + | − | − |

| 8 | Ant cerebrum | + | + | − | − |

| Cerebellum | + | + | − | − | |

| 9 | Mid-cerebrum | + | + | − | − |

| Cerebellum | + | + | − | − | |

| 10 | Mid-cerebrum, cerebellum | + | + | − | − |

| 11 | Ant cerebrum, | ++ | + | + | − |

| Mid-cerebrum | + | + | + | − | |

| Cerebellum, spinal cord | + | + | − | − | |

| 12 | Mid-cerebrum | + | + | ++ | − |

| 13 | Ant cerebrum | ++ | ++ | − | − |

| Mid-cerebrum | ++ | ++ | + | − | |

| 14 | Ant cerebrum | + | + | + | ++ |

| Medulla | + | + | − | + | |

| Cerebellum | + | + | − | − | |

| 15 | Ant cerebrum | + | + | + | ± |

| Mid-cerebrum | + | + | + | Occ. + | |

| Medulla and cerebellum | + | + | − | Occ. + | |

| Spinal cord | + | ± | − | − | |

| 16 | Ant cerebrum, pons | ++ | ++ | − | − |

| Cerebellum, spinal cord | + | ++ | − | − | |

| 17 | Ant cerebrum | + | + | − | − |

| Mid-cerebrum | + | + | − | − | |

| 18 | Ant cerebrum, mid-cerebrum, cerebellum | ++ | ++ | + | − |

| 19 | Medulla, cerebellum | ++ | ++ | − | − |

| Ant cerebrum, mid-cerebrum, spinal cord | ++ | + | + | − |

4G8*=positive staining using antibody to human β-amyloid (Aβ) and amyloid precursor protein (APP); AT8Ψ=positive staining using antibody to hyperphosphorylated-tau protein (AT8); Ant=anterior; pons=at the level of the pons; −=negative; +=positive; ++=intensely positive; Occ=occasional.

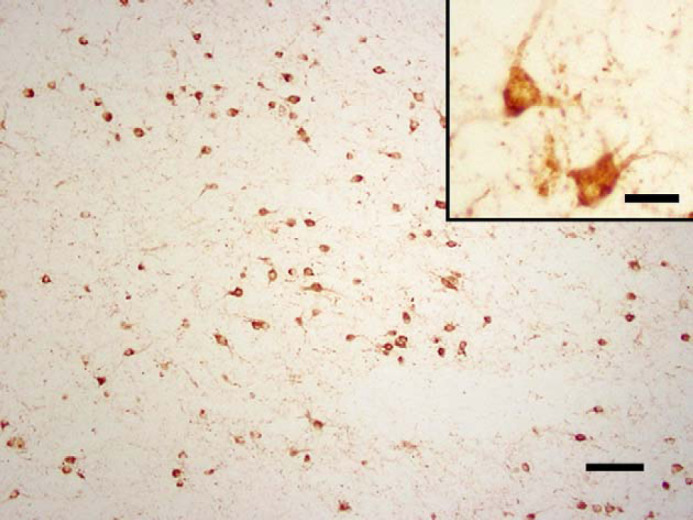

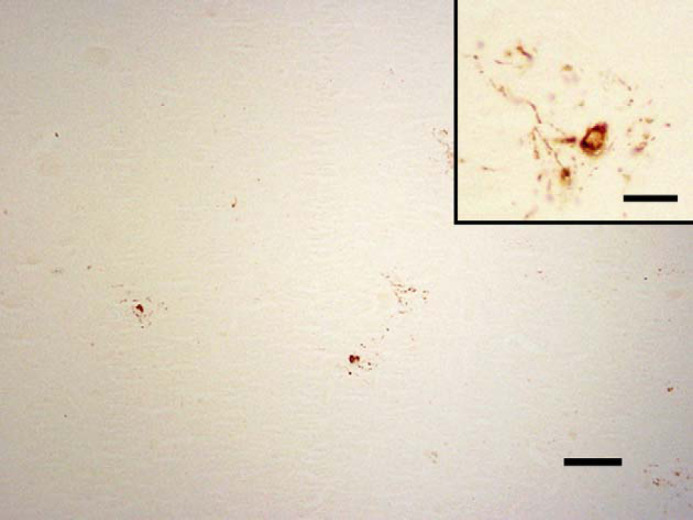

In two cats (cats 14 and 15), aged 11 and 13 years, neurons were intensely stained with AT8 (the antibody to hyperphosphorylated-tau). In both cases the stain was punctate and intracellular. In cat 14, many positively staining neurons were seen in the anterior cerebrum (Fig 3) and to a lesser extent, the medulla at the level of the vestibular nuclei. In cat 15, only occasional positively staining neurons were observed, and these had an irregular staining pattern (Fig 4). Most of these were situated within the dorsal medulla at the level of the cerebellar peduncles.

Fig 3.

Cat 14, brain, anterior cerebrum. AT8-immunoreactivity in neurons. Immunostain, antibody to hyperphosphorylated-tau protein (AT8), Bar, 100 μm. Inset: higher magnification of neurons, where the stain is punctate and intracellular. Inset bar, 25 μm.

Fig 4.

Cat 15, brain, dorsal medulla at the level of the cerebellar peduncles. AT8-immunoreactivity in occasional neurons. Immunostain, AT8, Bar, 100 μm. Inset: higher magnification of neurons with an irregular staining pattern. Bar, 25 μm.

Discussion

In the present study, intracellular staining of neurons and blood vessels was seen in all cats using the antibody to APP and Aβ (antibody 4G8). This is consistent with constitutive expression of APP, as has been shown in other mammalian species (Selkoe et al 1987, Head et al 2001). In contrast, only older cats were found to have more intense staining within or closely associated to their neurons and blood vessels, consistent with an age-dependent accumulation of Aβ. While Aβ is generally considered as an extracellular protein, it can also be detected within neurons (Hartmann et al 1997), accumulate along neuronal membranes (Head and Torp 2002), and become entrapped within the walls of cerebral arteries (Weller and Nicoll 2003).

Previous immunohistochemical studies have identified extracellular Aβ deposits (termed SP) in 14 out of 23 geriatric cats. However, only two cats of less than 4 years of age have previously been investigated, and neither were positive (Cummings et al 1996b, Nakamura et al 1996, Kuroki et al 1997, Head et al 2001, 2005). The results of the present study expand on these initial observations, finding extracellular Aβ deposits in seven of 19 cats (aged 16 weeks to 14 years), with all of the positive cats being over 10 years of age. In addition, the present study agrees with previous preliminary studies, showing that the extracellular Aβ deposits in cat brains take the form of diffuse plaques rather than well developed and circumscribed SP as are typically seen in people (Nakamura et al 1996, Head et al 2001, 2005, Georgia et al 2004). Their diffuse nature, the specificity of their immunostaining, and the lack of associated neuronal changes, suggest that the extracellular Aβ deposits of cats may be consistent with early diffuse plaques as described in human beings (Cummings et al 1996b, Georgia et al 2004, Head et al 2005).

The present study shows that the extracellular Aβ deposits typically have a patchy distribution within the deep cortical layers of the anterior, and occasionally, mid-cerebrum. Previous studies in cats have demonstrated Aβ deposits within multiple deep cortical layers of the temporal and occipital lobes (Nakamura et al 1996). In all cases the superficial layers of the cortex have not been involved (Nakamura et al 1996, Head et al 2005; findings in the present paper). This is similar to, although subtly different from, the changes seen in dogs, where the pattern of SP deposition has been shown to vary, not only between different regions of the brain, but also between individual dogs. In the prefrontal, parietal and occipital cortices, deposition tends to be patchy, with normal areas occurring close to extensive Aβ deposition. In contrast, the entorhinal cortex tends to be more homogeneously affected (Head et al 1998). Additionally, Aβ deposition within the cortex appears first in the deep cortical layers, with the more superficial layers being affected later (Satou et al 1997).

While the present study demonstrated intense AT8-immunoreactivity within the neurons of two aged cats, it failed to detect any fully developed NFT. This is in agreement with previous studies in both cats and dogs (Ball et al 1983, Selkoe et al 1987, Giaccone et al 1990, Wisniewski et al 1990, Cummings et al 1993, Kuroki et al 1997, Head et al 2005) which have shown that while mature NFT are not found, immunohistochemical staining can detect hyperphosphorylated tau within the cytoplasm of neurons, axons, apparently normal and dystrophic neurites, and oligodendrocytes (eg, using antibodies AT8 or PHF-1) (Kuroki et al 1997, Wegiel et al 1998, Head et al 2001, 2005). It has, therefore, been suggested that while dogs and cats do not form fully developed NFT, they may develop pre- or early tangle formation (Ball et al 1983, Selkoe et al 1987, Wegiel et al 1998, Giaccone et al 1990, Wisniewski et al 1990, Cummings et al 1993, Kuroki et al 1997, Head et al 2005). From the present study, cat 15 is of particular interest as the AT8-staining of its neurons had an irregular pattern suggestive of neurodegeneration, although this had not been observed on routine histology. In addition, Head et al (2005) demonstrated AT8-positivity in the hilus of the hippocampus of a geriatric cat where the neurons had a sprouting morphology similar to those more typically seen in people with AD.

At present it is not known whether neuronal AT8-immunoreactivity is associated with ageing per se, or with a specific cause of neurodegeneration. Support for its role in ageing comes from a study by Head et al (2005) which found two of five geriatric cats to be positive, while two younger cats were not. In addition, both cats with AT8-positive neurons in the present study were over 10 years of age (and they both had concurrent extracellular Aβ deposits, which we have shown is an age-related phenomena). However, both cats had previously experienced seizures. This is an interesting observation because tau hyperphosphorylation has been reported in the brains of humans who developed degenerative disease as a result of severe seizure activity (Burkhart et al 1998). In addition, one of the two cats with AT8-positive neurons reported by Head et al (2005) had also experienced seizures. Future studies on larger populations are needed to determine whether severe seizure activity may lead to the phosphorylation of tau, and what, if any, role this may play in the development of other neurological disorders.

Previous studies have suggested that there may be a degree of correlation between geriatric behavioural changes, Aβ deposition and, possibly, tau hyperphosphorylation (Cummings et al 1996b, Nakamura et al 1996, Head et al 2005). However, the number of cats studied is still very small. The present study found extracellular Aβ deposits in the majority (seven of nine) of the cats older than 10 years of age, all of which had clinical evidence of neurological dysfunction. Unfortunately, it was not possible to determine whether the presence of neurological dysfunction was significant. This is because the majority of the cats examined (17 of 19) had some kind of neurological disorder. In addition, there appears to be no obvious correlation between the nature of the clinical signs of neurological dysfunction and presence of positive staining for either extracellular Aβ deposits or AT8-immunoreactivity. However, it is possible that the lack of these changes in the young cats with neurological dysfunction may suggest that advancing age and neurological dysfunction could act in synergy to cause the deposition of extracellular Aβ deposits and neuronal AT8-immunoreactivity.

In conclusion, this study has shown that while APP is constitutively expressed within cat brains, the intensity of the staining within, or closely associated to, neurons and blood vessels appears to be age-dependent, consistent with Aβ accumulation. The development of diffuse extracellular Aβ deposits also appears to be age related and was found most frequently in the anterior cerebrum of the affected cats. The presence of neurons showing AT8-immunoreactivity also appears to be age related, and occurred concurrently with extracellular Aβ deposition. The changes found were generally similar to those observed in aged people and other mammals. Our studies indicate that future investigations will have to involve a much larger number of cats to determine whether the histopathological changes described in this paper relate to the presence of particular disease processes and whether or not particular breeds of cat may be predisposed.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by a grant from BSAVA Petsavers. Initial studies by FG-M were supported by the Cunningham Trust and the Medical Research Council. DG-M's lectureship was supported by Nestlé Purina Petcare. The authors wish to thank all members of the Department of Clinical Veterinary Science, University of Bristol, who were involved in the initial investigations and/or care of the cats used in this study. We thank Mr A Skuse for expert assistance with the figures.

References

- Ball M.J., MacGregor J., Fyfe I.M., Papoport S.I., London E. Paucity of morphological changes in the brains of aging beagle dogs: further evidence the Alzheimer lesions are unique for primate central nervous system, Neurobiology of Aging 4, 1983, 127–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumcke I., Zuschratter W., Schewe J.C., Suter B., Lie A.A., Riederer B.M., et al. Cellular pathology of hilar neurons in Ammon's horn sclerosis, Journal of Comparative Neurology 414 (4), 1999, 437–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H., Braak E., Strothjohann M. Abnormally phosphorylated tau protein related to the formation of neurofibrillary tangles and neuropil threads in the cortex of sheep and goat, Neuroscience Letters 171, 1994, 1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw J.M., Pearson G.R., Gruffydd-Jones T.J. A retrospective study of 286 cases of neurological disorders of the cat, Journal of Comparative Pathology 131, 2004, 112–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broussard J.D., Peterson M.E., Fox P.R. Changes in clinical and laboratory findings in cats with hyperthyroidism from 1983 to 1993, Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 206 (3), 1995, 302–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobik M., Thompson T., Russell M.J. Amyloid deposition in various breeds of dog [abstract], Abstracts in Neuroscience 20, 1994, 172. [Google Scholar]

- Burkhart K.K., Beard D.C., Lehman R.A., Billingsley M.L. Alterations in tau phosphorylation in rat and human neocortical brain slices following hypoxia and glucose deprivation, Experimental Neurology 154 (2), 1998, 464–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman B.L., Voith V.L. Behavioral problems in old dogs: 26 cases (1984–1987), Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 196 (6), 1990, 944–946. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings B.J., Su J.H., Cotman C.W., White R., Russell M.J. β-Amyloid accumulation in aged canine brain: a model of plaque formation in Alzheimer's disease, Neurobiology of Aging 14, 1993, 547–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings B.J., Head E., Ruehl W., Milgram N.W., Cotman C.W. The canine as an animal model of human aging and dementia, Neurobiology of Aging 17, 1996a, 259–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings B.J., Satou T., Head E., Milgram N.W., Cole G.M., Savage M.J., et al. Diffuse plaques contain C-terminal Aβ42 and not Aβ40: evidence from cats and dogs, Neurobiology of Aging 17 (4), 1996b, 653–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson D.W., Crystal H.A., Bevona C., Honer W., Vincent I., Davies P. Correlations of synaptic and pathological markers with cognition of the elderly, Neurobiology of Aging 16, 1995, 285–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgia B., Nikalaos P., Stephanos L., Ioannis V. (2004) Immunohistochemical investigation of amyloid β protein (Aβ) in the brain of aged cats. Proceedings of the 22nd ESVP meeting, Olsztyn, Poland, 15–18th September, p. 57.

- Giaccone G., Verga L., Finazzi M., Pollo B., Tagliavini F., Frangione B., et al. Cerebral preamyloid deposits and congophilic angiopathy in aged dogs, Neuroscience Letters 114, 1990, 178–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goedert M. Tau protein and the neurofibrillary pathology of Alzheimer's disease, Trends in Neuroscience, 1993, 460–465. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hardy J.A., Higgins G.A. Alzheimer's disease: the Amyloid cascade hypothesis, Science 256, 1992, 184–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison J., Buchwald J. Auditory brainstem responses in the aged cat, Neurobiology of Aging 3, 1982, 163–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison J., Buchwald J. Eye blink conditioning deficits in the old cat, Neurobiology of Aging 4, 1983, 45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann T., Bieger S.C., Bruhl B., Tienari P., Ida N., Allsop D., et al. Distinct sites of intracellular production for Alzheimer's disease A beta40/42 amyloid peptides, Nature Medicine 3, 1997, 1016–1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Head E. Brain aging in dogs: parallels with human brain aging and Alzheimer's disease, Veterinary Therapeutics 2 (3), 2001, 247–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Head E., Torp R. Insights into Aβ and presenilin from a canine model of human brain aging, Neurobiology of Disease 9, 2002, 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Head E., Callahan H., Muggenburg B.A., Cotman C.W., Milgram N.W. Visual-discrimination learning ability and β-Amyloid accumulation in the dog, Neurobiology of Aging 19 (5), 1998, 415–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Head E., McCleary R., Hahn F.F., Milgram N.W., Cotman C.W. Region-specific age at onset of β-amyloid in dogs, Neurobiology of Aging 21, 2000, 89–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Head E., Milgram N.W., Cotman C.W. Neurobiological methods of aging in the dog and other vertebrate species. Hof, Mobbs Functional Neurobiology of Aging, 2001, Academic Press: San Diego, 457–468. [Google Scholar]

- Head E., Moffatt K., Das P., Sarsoza F., Poon W.W., Landsburg G., et al. β-Amyloid deposition and tau phosphorylation in clinically characterized aged cats, Neurobiology of Aging 26, 2005, 749–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamoto T., Ogomori K., Tateishi J., Prusiner S.B. Formic acid pretreatment enhances immunostaining of cerebral and systemic amyloids, Laboratory Investigations 57 (2), 1987, 230–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroki K., Uchida K., Kiatipattanasakul W., Nakamura S., Yamaguchi R., Nakayama H., et al. Immunohistochemical detection of tau proteins in various non-human animal brains, Neuropathology 17, 1997, 174–180. [Google Scholar]

- Levine M.S., Lloyd R.L., Fisher R.S., Hull C.D., Buchwald N.A. Sensory, motor and cognitive alterations in aged cats, Neurobiology of Aging 8, 1987, 253–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson M.P. Pathways towards and away from Alzheimer's disease, Nature 430, 2004, 631–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milgram N.W., Head E., Weiner E., Thomas E. Cognitive functions and aging in the dog: acquisition of non-spatial visual tasks, Behavioural Neuroscience 108, 1994, 57–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffat K.S., Landsberg G.M. An investigation of the prevalence of clinical signs of cognitive dysfunction syndrome (CDS) in cats [abstract], Journal of the American Animal Hospital Association 39, 2003, 512. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan D. Comparative aspects of ageing, Veterinary Times, September 2002, 11–12.

- Nakamura S., Nakayama H., Kiatipattanasakul W., Uetsuka K., Uchida K., Goto N. Senile plaques in very aged cats, Acta Neuropathology 91, 1996, 437–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riederer B.M., Mourton-Gilles C., Frey P., Delacoute A., Probst A. Differential phosphorylation of tau proteins during kitten brain development and Alzheimer's disease, Journal of Neurocytology 30, 2001, 145–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruehl W.W., Bruyette D.S., DePaoli A., Cotman C.W., Head E., Milgram N.W., et al. Canine cognitive dysfunction as a model for human age-related cognitive decline, dementia, and Alzheimer's disease: clinical presentation, cognitive testing, pathology and response to l-deprenyl therapy, Progress in Brain Research 106, 1995, 217–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satou T., Nielson K.A., Cummings B.J., Hahn F.F., Head E., Milgram N.W., et al. The progression of β-amyloid deposition in the frontal cortex of the aged canine, Brain Research 774, 1997, 35–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selkoe D.J. Alzheimer's disease: genotypes, phenotype, and treatments, Science 275, 1997, 630–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selkoe D.J., Bell D.S., Podlisny M.B., Price D.L., Cork L.C. Conservation of brain amyloid proteins in aged mammals and humans with Alzheimer's disease, Science 235, 1987, 873–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trojanowski J.Q., Schmidt M.L., Shin R.-W., Bramblett G.T., Goedert M., Lee V.M.-Y. PHF tau (A68): from pathological marker to potential mediator of neuronal dysfunction and degeneration in Alzheimer's disease, Clinical Neuroscience 1, 1993, 184–191. [Google Scholar]

- Wegiel J., Wisniewski H.M., Soltysiak Z. Region and cell type specific pattern of tau phosphorylation in dog brain, Brain Research 802, 1998, 259–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weller R.O., Nicoll J.A. Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy: pathogenesis and effects on the ageing and Alzheimer brain, Neurological Research 25 (6), 2003, 611–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisniewski H.M., Wegiel J., Morys J., Bancher C., Soltysiak Z., Kim K.S. Aged dogs: an animal model to study beta-protein amyloidogenesis. Maurer P.R.K., Beckman H. Alzheimer's Disease. Epidemiology, Neurology, Neurochemistry and Clinics, 1990, Springer-Verlag: New York, 151–167. [Google Scholar]