Abstract

Background

Perineal damage occurs frequently during childbirth, with severe damage involving injury to the anal sphincter reported in up to 18% of vaginal births. Women who have sustained anal sphincter damage are more likely to suffer perineal pain, dyspareunia (painful sexual intercourse), defaecatory dysfunction, and urinary and faecal incontinence compared to those without damage. Interventions in a subsequent pregnancy may be beneficial in reducing the risk of further severe trauma and may reduce the risk of associated morbidities.

Objectives

To examine the effects of Interventions for women in subsequent pregnancies following obstetric anal sphincter injury for improving health.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register (30 September 2014).

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials, cluster‐randomised trials and multi‐arm trials assessing the effects of any intervention in subsequent pregnancies following obstetric anal sphincter injury to improve health. Quasi‐randomised controlled trials and cross‐over trials were not eligible for inclusion.

Data collection and analysis

No trials were included. In future updates of this review, at least two review authors will extract data and assess the risk of bias of included studies.

Main results

No eligible completed trials were identified. One ongoing trial was identified.

Authors' conclusions

No relevant trials were included. The effectiveness of interventions for women in subsequent pregnancies following obstetric anal sphincter injury for improving health is therefore unknown. Randomised trials to assess the relative effects of interventions are required before clear practice recommendations can be made.

Keywords: Adult, Female, Humans, Pregnancy, Anal Canal, Anal Canal/injuries, Obstetric Labor Complications, Obstetric Labor Complications/prevention & control, Recurrence

Plain language summary

Interventions for women in pregnancies following obstetric anal sphincter injury to reduce the risk of recurrent injury and harms

Three quarters of women who give birth vaginally sustain damage to the area between their vagina and anus (the perineum). Severe damage, involving the anal sphincter is less common, occurring in up to a fifth of vaginal births. Reported rates of anal sphincter damage vary widely which may be due to several reasons including: under and over reporting, use of different diagnostic criteria, different assessment methods and differences in training in the recognition of damage.

Sphincter damage is associated with an increased risk of short‐ and long‐term ill‐health including perineal pain, painful intercourse, bowel dysfunction, and urinary and faecal incontinence. Perineal pain following birth can affect maternal and infant bonding, ability to breastfeed and may increase the risk of urinary retention and painful intercourse, reduce well‐being and increase the risk of depression.

Women who have sustained sphincter damage during childbirth who become pregnant again, may benefit from a number of interventions to reduce the risk of repeated damage. These interventions include: antenatal pelvic floor exercises and biofeedback training to strengthen the pelvic floor; perineal massage or creams to reduce the risk of perineal tearing, or interventions during labour aimed at reducing the risk of sphincter damage including: earlier induction of labour to reduce the risk of a large baby, elective caesarean section to avoid perineal damage, vacuum extraction as opposed to forceps and selective episiotomy to reduce the risk of severe perineal damage.

Only one ongoing randomised trial was identified evaluating caesarean section compared with vaginal birth for women in subsequent pregnancies following obstetric anal sphincter injury to reduce the risk of recurrent injury and associated harms. High‐quality, adequately‐powered trials are therefore required to evaluate the relative effectiveness of different interventions to improve health in subsequent pregnancies following obstetric anal sphincter injury.

Background

Perineal trauma (damage to the area between the vagina and anus) occurs in over three‐quarters of vaginal births (Albers 1999; McCandlish 1998). Obstetric anal sphincter injury (OASI) is perineal trauma involving the anal sphincter (the ring of muscle controlling the entrance to the rectum). OASI is the severe end of the spectrum of perineal trauma and is associated with increased morbidity. Primary OASI (OASI occurring for the first time), affects up to 18% (range 1.7% to 18%) of vaginal births (Harkin 2003; Hirayama 2012; Lowder 2007). Recurrent OASI (OASI in a subsequent pregnancy, previously affected by OASI) affects up to 7.2% of vaginal births (range 4.0% to 7.2%) (Dandolu 2005; Edozien 2014; Harkin 2003; Payne 1999; Peleg 1999). There is wide variation in reported rates of OASI between countries (Hirayama 2012), which may be due to under or over reporting, differences in training in the recognition of OASI and the variety of tools used to identify injury. Tools used include: clinical examination, endoanal ultrasonography (use of an ultrasound probe to identify sphincter damage), anal manometry (use of a pressure sensitive probe to measure muscle tone) and patient questionnaires (to assess symptoms and quality of life).

Incidence rate and predisposing risk factors

Incidence rate reporting is complex. The inclusion or exclusion of women with differing risk factors (for example, use of forceps or episiotomy) will alter the denominator population and influence the incidence rate of OASI reported (Abbott 2010). Also the rate is sometimes reported for the whole obstetric population (all primiparous and multiparous births, which will include women with previous OASI) (Hirayama 2012) and sometimes the rate is reported as a subset of the whole obstetric population, for example primiparous (Gurol‐Urganci 2013) or instrumental births only (de Leeuw 2007).

The incidence of OASI seems to be increasing (Gurol‐Urganci 2013; Laine 2009; McLeod 2003). Gurol‐Urganci 2013 reported that the OASI rate tripled in England between 2000 and 2012, (1.8% to 5.9%) and that improved recognition and standardised classification of perineal trauma and changes in second stage care practices such as the declining use of episiotomy, may be contributing to the increasing incidence.

The risk of recurrent OASI was found to be five‐fold higher than the risk for multiparous births with no history of OASI, the number of women included in this study were few and only two women (4.4% confidence interval (CI) 0.54 to 15.5) sustained a subsequent OASI (Harkin 2003). This finding however is supported by Edozien 2014 who reported a five‐fold increase in risk of recurrent OASI (adjusted odds ratio (OR) 5.5, 95% CI 5.2 to 5.9) using data from over 639,000 births. Dandolu 2005 examined 258,507 vaginal births and found that 18,888 (7.31%) women sustained a primary OAIS, 14,990 of these women went on to have a further vaginal birth and 864 (5.76%) sustained a recurrent OASI. Women with a primary fourth degree tear seemed at greater risk of OASI recurrence compared to women with a primary third degree tear (7.73% versus 4.69%) and overall, instrumental delivery accompanied by an episiotomy conveyed the greatest risk of OASI reoccurrence (17.7%). Episiotomy alone increased the risk of recurrent OASI by 50%. Jango 2012 reported a lower rate of primary OASI (7336/159,446, 4.6%) and higher rate of recurrent OASI (521/7336, 7.1%) compared to Dandolu 2005. Jango 2012 found increasing birth weight, ventouse (forceps was not performed in this population) and shoulder dystocia were associated with increased risk of a OASI but episiotomy use was not. The detrimental effect of episiotomy use in women with a previous OAS reported by Dandolu 2005 is opposite to the protective effect reported for episiotomy use during births of primiparous women or women without a history of OASI (de Leeuw 2007; Gurol‐Urganci 2013). The reasons for this difference are unclear, but may be due to increased risk of episiotomy extension from previous perineal scarring (Dandolu 2005).

Asian ethnicity seems to increase the risk of OASI, but this effect seems limited to South Asian women living outside Asia (Wheeler 2011). Increasing maternal age, primiparity, induction and augmentation of labour, length of second stage of labour (> two hours), forceps delivery, increased neonatal head circumference, occiput posterior position and birthweight greater than 4 kg are associated with an increased risk of primary and recurrent OASI (Dandolu 2005; Fizgerald 2007; Hirayama 2012; Kudish 2008; Payne 1999; Peleg 1999; Williams 2005).

Data regarding the incidence of primary and recurrent OASI and the influence of risk factors are limited and sometimes conflicting. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) intrapartum care guidance however, suggests the risk of recurrent severe trauma is similar to the risk of severe trauma at first vaginal birth, though this guidance is currently being updated (NICE 2007).

Adverse effects

OASI is associated with an increased risk of short‐ and long‐term morbidity which could seriously affect quality of life. Sequelae include: perineal pain (Macarthur 2004), dyspareunia (painful sexual intercourse) (Rathfisch 2010), defaecatory dysfunction, and urinary and faecal incontinence (Fenner 2003; MacArthur 1997; Richter 2006). Perineal pain is an immediate consequence that may adversely affect maternal and infant bonding, ability to breastfeed, increase the risk of urinary retention and dyspareunia (Barrett 2000; Buhling 2006), and could reduce well‐being and increase the risk of depression (Brown 2000).

Possibly the most distressing adverse effect of OASI is anal incontinence related to anal sphincter injury and pudendal nerve damage (Fynes 1998). Four per cent of women report faecal incontinence following vaginal birth (MacArthur 1997). The incidence of anal incontinence is related to the severity of the sphincter defect observed at follow‐up. For example, following clinically identified severe perineal trauma at the time of birth, 13% of women without identifiable sphincter defects on postnatal endo‐anal ultrasound (EAUS) reported anal incontinence, whereas 64% with internal and external defects on EAUS reported anal incontinence (Laine 2011). Incontinence rates may worsen with time and following subsequent births irrespective of degree of perineal trauma sustained (Baghestan 2012; Bek 1992). Various factors have been identified that may help determine the risk of anal incontinence following a subsequent birth; these include: age, parity, presence and severity of symptoms, EAUS‐identified injury and impaired sphincter function assessed by manometry.

Anal incontinence in the absence of identified OASI at the time of birth, may be in part due to pudendal nerve damage or unidentified anal sphincter damage. Sultan 1993 identified over 30% more anal sphincter injuries using EAUS compared with clinical examination alone. This difference may, however, be related to the experience of and/or technique used by the person undertaking the initial clinical examination rather than the superior or sensitivity of EAUS (Andrews 2006).

Identification of Injury

All women who have sustained perineal trauma should have a systematic examination of the vagina, perineum and rectum, including rectal examination before and after perineal repair by an experienced practitioner trained in the recognition and management of perineal tears (NICE 2007; RCOG 2007). Methods of OASI repair OASI have been examined in a separate Cochrane review (Fernando 2006). To our knowledge, there are no reviews examining suture materials for repair of OASI, the ideal clinician to perform the repair (obstetrician or colorectal surgeon), effectiveness of immediate versus delayed repair, prevention of OASI, or interventions for women in subsequent pregnancies following OASI to reduce the risk of recurrent injury and associated harms.

Description of the condition

NICE and the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists guidelines (NICE 2007; RCOG 2007) recommend perineal or genital trauma caused by either tearing or episiotomy at birth should be defined as follows (described by Sultan 1999):

first degree – injury to skin only;

second degree – injury to the perineal muscles, but not the anal sphincter;

third degree – injury to the perineum involving the anal sphincter complex:

3a – less than 50% of external anal sphincter (EAS) thickness torn;

3b – more than 50% of EAS thickness torn;

3c – internal anal sphincter (IAS) torn;

fourth degree – injury to the perineum involving the anal sphincter complex (external and internal anal sphincter) and anal epithelium.

OASI includes third and fourth‐degree perineal tears (RCOG 2007).

Description of the intervention

Antenatal interventions for women who have sustained a previous obstetric anal sphincter injury include: pelvic floor exercises that aim to strengthen the pelvic floor and have recently been found to reduce the risk of urinary incontinence (Stafne 2012); biofeedback training which uses computer‐generated feedback from rectal balloons to (a) improve patient awareness of the presence of faecal material in the rectum and (b) to co‐ordinate contraction of the external anal sphincter with relaxation of the internal sphincter and (c) improve the force of the muscle (Miner 1990; Norton 2012); or stimulation of the sacral nerves that control the lower part of the bowel and sphincters by inserting electrodes in the lower back and connecting them to a pulse generator (Mowatt 2007). Other antenatal interventions include: perineal massage or creams that aim to reduce the risk of perineal tearing.

Intrapartum interventions include: induction of labour to reduce the risk of macrosomia (infant birth weight greater than 4 kg) and subsequent risk of trauma; elective caesarean section to avoid vaginal and perineal trauma; vacuum extraction rather than forceps to reduce the risk of vaginal and perineal trauma; selective episiotomy to reduce the risk of severe perineal trauma; and different flexion techniques of the presenting fetal part to reduce the diameter and in doing so, reduce the risk of subsequent trauma.

How the intervention might work

Interventions may aim to improve the integrity of the anal sphincter (pelvic floor muscle exercises, electrical stimulation), avoid trauma (elective caesarean section) or reduce the risk of trauma (medio‐lateral episiotomy, vacuum and flexion techniques) to the perineum and anal sphincter and in doing so reduce the risk of adverse effects such as incontinence.

Why it is important to do this review

There are currently no systematic reviews, evidence‐based guidance on interventions or strategies for women in subsequent pregnancies following obstetric anal sphincter injury to prevent or reduce the risk of further damage/trauma to the anal sphincter complex. Guidance based on robust evidence would improve the care in subsequent pregnancies for women who have previously sustained a third‐degree tear and in doing so reduce the risk of morbidity and improve health.

Objectives

The objective of this review was to assess the effects of antenatal and intrapartum interventions for women in subsequent pregnancies following a previous obstetric anal sphincter injury to reduce the risk of recurrent injury and associated harms.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We planned to include abstracts, published and unpublished randomised controlled trials, cluster‐randomised trials and multi‐arm trials assessing the effects of any intervention in subsequent pregnancies following obstetric anal sphincter injury. Quasi‐randomised controlled trials and trials using a cross‐over design were not eligible for inclusion.

Types of participants

All pregnant women who sustained obstetric anal sphincter injury during a previous birth.

Types of interventions

Any type of intervention (irrespective of when the intervention is delivered i.e. antenatal or intrapartum) aimed at reducing the risk of harm in a subsequent pregnancy following obstetric anal sphincter injury compared with any other intervention or with routine care, i.e. antenatal interventions; such as massage or creams and intrapartum interventions such as vacuum versus selective or routine episiotomy and selective or routine episiotomy with routine care. Different types of the same category of intervention (antenatal or intrapartum) i.e. vacuum versus forceps and flexion of the presenting part versus hands poised or different types of creams.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Incidence of recurrent third‐/fourth‐degree tear (as defined by authors of individual trials)

Anal incontinence (flatus, fluid and solid stool)

Secondary outcomes

Perinatal

Induction of labour

Instrumental vaginal birth (forceps and vacuum)

Caesarean birth

Perineal trauma (as defined by authors of individual trials)

Gestational age at birth

Birthweight

Admission to special care baby unit

Breastfeeding

Maternal well‐being and quality of life

Long term

Dyspareunia (as defined by authors of individual trials)

Perineal pain (as defined by authors of individual trials)

Resumption of sexual intercourse

Presence of symptoms of anal sphincter damage (as defined by authors of individual trials and including: flatal (accidental leakage of gas) and faecal incontinence, urgency, urinary incontinence)

Maternal well‐being and quality of life (at all time points reported)

Other outcome

1. Cost (as defined by authors of individual trials)

Search methods for identification of studies

The following methods section of this review was based on a standard template used by the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Electronic searches

We contacted the Trials Search Co‐ordinator to search the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register (30 September 2014).

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register is maintained by the Trials Search Co‐ordinator and contains trials identified from:

monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE;

weekly searches of Embase;

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Details of the search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE and Embase, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service can be found in the ‘Specialized Register’ section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Trials identified through the searching activities described above are each assigned to a review topic (or topics). The Trials Search Co‐ordinator searches the register for each review using the topic list rather than keywords.

We did not apply any language or date restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

No completed trials meeting our criteria for inclusion were identified. Methods of data collection and analysis to be used in future updates of this review are provided in Appendix 1.

Results

Description of studies

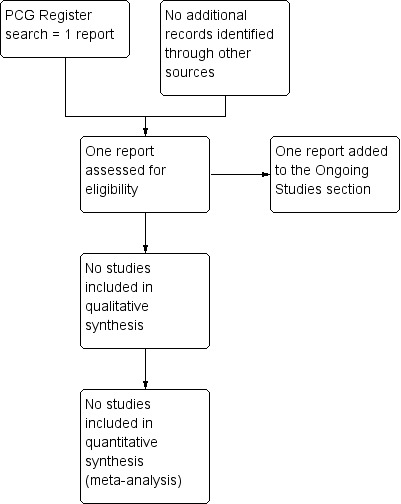

No completed trials that met the inclusion criteria of the review were identified. One ongoing trial was identified (NCT00632567) Figure 1; for more details, see Characteristics of ongoing studies.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Results of the search

The search retrieved one trial report of an ongoing study (Abramowitz 2008).

Included studies

No randomised trials were found for inclusion in the review.

Excluded studies

There are no excluded studies.

Risk of bias in included studies

Not applicable.

Effects of interventions

No randomised trials were found for inclusion in the review.

Discussion

We identified one ongoing trial (Abramowitz 2008) that will evaluate the relative effects of caesarean birth versus vaginal birth in women who have previously had an anal sphincter rupture diagnosed with anal endosonography.

Evidence on short‐ and long‐term sequelae following primary and secondary obstetric anal sphincter injury (OASI) are limited. However, health and well‐being seem to be severely adversely affected (Brown 2000; Rathfisch 2010; Richter 2006) and these effects may worsen as the woman ages (Fornell 2005). Consequently, interventions for women in subsequent pregnancies following OASI to limit or prevent further sphincter damage may convey substantial health benefits. To date there is no evidence from completed randomised trials, it is therefore important to undertake such trials to identify clinically and cost‐effective interventions for improving the health of these women.

Summary of main results

The effects of interventions for women in subsequent pregnancies following OASI for improving health is unknown.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

No randomised trials were found for inclusion in the review.

Quality of the evidence

No randomised trials were found for inclusion in the review.

Potential biases in the review process

No randomised trials were found for inclusion in the review.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

No randomised trials were found for inclusion in the review.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The effects of interventions for women in subsequent pregnancies following obstetric anal sphincter injury (OASI) for improving health is unknown. Women should be provided with this information when planning a subsequent pregnancy following OASI.

Implications for research.

Well‐designed randomised trials are required to evaluate interventions for women in subsequent pregnancies following OASI for improving health.

Acknowledgements

As part of the pre‐publication editorial process, this review has been commented on by three peers (an editor and two referees who are external to the editorial team), a member of the Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's international panel of consumers and the Group's Statistical Adviser.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Methods of 'Data collection and analysis' to be used in future updates of this review

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors will independently assess for inclusion all the potential studies we identify as a result of the search strategy. We will resolve any disagreement through discussion or, if required, we will consult the third review author.

Data extraction and management

We will design a form to extract data. For eligible studies, two review authors will extract the data using the agreed form. We will resolve discrepancies through discussion or, if required, we will consult the third review author. We will enter data into Review Manager software (RevMan 2014) and check for accuracy.

When information regarding any of the above is unclear, we will attempt to contact authors of the original reports to provide further details.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors will independently assess risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We will resolve any disagreement by discussion or by involving a third assessor.

In addition to the checks below undertaken for trials comparing one intervention with another, we will assess the risk of bias in multifactorial studies by assessing the risk that data are not presented for each of the groups to which participants were randomised (low, high or unclear risk of bias) and the risk that the study has selectively reported comparisons of intervention arms for some or all outcomes (low, high or unclear risk of bias).

(1) Random sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

We will describe for each included study the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups.

We will assess the method as:

low risk of bias (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator);

high risk of bias (any non‐random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number);

unclear risk of bias.

(2) Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

We will describe for each included study the method used to conceal allocation to interventions prior to assignment and we will assess whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during recruitment, or changed after assignment.

We will assess the methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

high risk of bias (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth);

unclear risk of bias.

(3.1) Blinding of participants and personnel (checking for possible performance bias)

We will describe for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We will consider that studies are at low risk of bias if they were blinded, or if we judge that the lack of blinding would be unlikely to affect results. We will assess blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We will assess the methods as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias for participants;

low, high or unclear risk of bias for personnel.

(3.2) Blinding of outcome assessment (checking for possible detection bias)

We will describe for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind outcome assessors from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We will assess blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We will assess methods used to blind outcome assessment as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias.

(4) Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias due to the amount, nature and handling of incomplete outcome data)

We will describe for each included study, and for each outcome or class of outcomes, the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We will state whether attrition and exclusions were reported and the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomised participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. Where sufficient information is reported, or can be supplied by the trial authors, we will re‐include missing data in the analyses which we undertake.

We will assess methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. no missing outcome data or less than 20% missing; missing outcome data balanced across groups);

high risk of bias (e.g. numbers or reasons for missing data imbalanced across groups; ‘as treated’ analysis carried out with substantial departure of intervention received from that assigned at randomisation);

unclear risk of bias.

(5) Selective reporting (checking for reporting bias)

We will describe for each included study how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found.

We will assess the methods as:

low risk of bias (where it is clear that all of the study’s pre‐specified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review have been reported);

high risk of bias (where not all the study’s pre‐specified outcomes have been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified; outcomes of interest are reported incompletely and so cannot be used; study fails to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported);

unclear risk of bias.

(6) Other bias (checking for bias due to problems not covered by (1) to (5) above)

We will describe for each included study any important concerns we have about other possible sources of bias.

We will assess whether each study was free of other problems that could put it at risk of bias:

low risk of other bias;

high risk of other bias;

unclear whether there is risk of other bias.

(7) Overall risk of bias

We will make explicit judgements about whether studies are at high risk of bias, according to the criteria given in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). With reference to (1) to (6) above, we will assess the likely magnitude and direction of the bias and whether we consider it is likely to impact on the findings. We will explore the impact of the level of bias through undertaking sensitivity analyses ‐ see Sensitivity analysis.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, we will present results as summary risk ratio with 95% confidence intervals.

Continuous data

For continuous data, we will use the mean difference if outcomes are measured in the same way between trials. We will use the standardised mean difference to combine trials that measure the same outcome, but use different methods.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised trials

We will include cluster‐randomised trials in the analyses along with individually‐randomised trials. We will adjust their sample sizes using the methods described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions using an estimate of the intracluster correlation co‐efficient (ICC) derived from the trial (if possible), from a similar trial or from a study of a similar population. If we use ICCs from other sources, we will report this and conduct sensitivity analyses to investigate the effect of variation in the ICC. If we identify both cluster‐randomised trials and individually‐randomised trials, we plan to synthesise the relevant information. We will consider it reasonable to combine the results from both if there is little heterogeneity between the study designs and the interaction between the effect of intervention and the choice of randomisation unit is considered to be unlikely.

We will also acknowledge heterogeneity in the randomisation unit and perform a sensitivity analysis to investigate the effects of the randomisation unit.

Dealing with missing data

For included studies, we will note levels of attrition. We will explore the impact of including studies with high levels of missing data in the overall assessment of treatment effect by using sensitivity analysis.

For all outcomes, we will carry out analyses, as far as possible, on an intention‐to‐treat basis, i.e. we will attempt to include all participants randomised to each group in the analyses, and all participants will be analysed in the group to which they were allocated, regardless of whether or not they received the allocated intervention. The denominator for each outcome in each trial will be the number randomised minus any participants whose outcomes are known to be missing.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We will assess statistical heterogeneity in each meta‐analysis using the T², I² and Chi² statistics. We will regard heterogeneity as substantial if the I² is greater than 30% and either the T² is greater than zero, or there is a low P value (less than 0.10) in the Chi² test for heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

If there are 10 or more studies in the meta‐analysis we will investigate reporting biases (such as publication bias) using funnel plots. We will assess funnel plot asymmetry visually. If asymmetry is suggested by a visual assessment, we will perform exploratory analyses to investigate it.

Data synthesis

We will carry out statistical analysis using the Review Manager software (RevMan 2014). We will use fixed‐effect meta‐analysis for combining data where it is reasonable to assume that studies are estimating the same underlying treatment effect: i.e. where trials are examining the same intervention, and the trials’ populations and methods are judged sufficiently similar. If there is clinical heterogeneity sufficient to expect that the underlying treatment effects differ between trials, or if substantial statistical heterogeneity is detected, we will use random‐effects meta‐analysis to produce an overall summary if an average treatment effect across trials is considered clinically meaningful. The random‐effects summary will be treated as the average range of possible treatment effects and we will discuss the clinical implications of treatment effects differing between trials. If the average treatment effect is not clinically meaningful, we will not combine trials.

If we use random‐effects analyses, the results will be presented as the average treatment effect with 95% confidence intervals, and the estimates of T² and I².

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

If we identify substantial heterogeneity, we will investigate it using subgroup analyses and sensitivity analyses. We will consider whether an overall summary is meaningful, and if it is, use random‐effects analysis to produce it.

We plan to carry out the following subgroup analyses.

Ethnicity (comparison of women of South Asian, black, middle Eastern or Hispanic ethnicity with each other and with women of white European descent.

Maternal age (less than 35 years of age versus 35 years of age or older).

Number of previous births with anal sphincter injury (once versus twice or more).

Type of previous vaginal birth (instrumental (ventouse and forceps) versus normal).

Macrosomia (less than 4 kg versus 4 kg or more).

We will use primary outcomes in subgroup analyses.

We will assess subgroup differences by interaction tests available within RevMan (RevMan 2014). We will report the results of subgroup analyses quoting the χ2 statistic and P value, and the interaction test I² value.

Sensitivity analysis

We will carry out sensitivity analysis to explore the effects of trial quality assessed by allocation concealment and other risk of bias components, by omitting studies rated as inadequate for these components. If there is statistical heterogeneity, we will explore the effects of random‐effects analyses. Sensitivity analysis will be restricted to the primary outcomes.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of ongoing studies [ordered by study ID]

Abramowitz 2008.

| Trial name or title | EPIC: Anal incontinence after delivery. Secondary prevention with caesarean section |

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

|

| Interventions | Caesarean section versus vaginal delivery. |

| Outcomes | Median incontinence VAIZEY score at 6 months. |

| Starting date | March 2008 (estimated October 2014). |

| Contact information | Laurent Abramowitz, MD +33(0)1 40 25 80 80 ext bip 2225 laurent.abramowitz@bch.aphp.fr |

| Notes | NCT00632567 |

Contributions of authors

Diane Farrar wrote the first drafts of the protocol and review.Drafts were developed and amended by Diane Farrar following review and suggestions from Carmel Ramage and Derek Tuffnell.

Declarations of interest

None known.

New

References

References to ongoing studies

Abramowitz 2008 {published data only}

- Abramowitz L. EPICc: anal incontinence after delivery. Secondary prevention with caesarean section. ClinicalTrials.gov (http://clinicaltrials.gov/) 2008.

Additional references

Abbott 2010

- Abbott D, Atere‐Roberts N, Williams A, Oteng‐Ntim E, Chappell LC. Obstetric anal sphincter injury. BMJ 2010;341:140‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Albers 1999

- Albers L, Garcia J, Renfrew M, McCandlish R, Elbourne D. Distribution of genital tract trauma in childbirth and related postnatal pain. Birth 1999;26:11‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Andrews 2006

- Andrews V, Sultan AH, Thakar R, Jones PW. Occult anal sphincter injuries—myth or reality?. BJOG: an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology 2006;113:195‐200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Baghestan 2012

- Baghestan E, Irgens LM, Børdahl PE, Rasmussen S. Risk of recurrence and subsequent delivery after obstetric anal sphincter injuries. BJOG: an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology 2012;119:62‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Barrett 2000

- Barrett G, Pendry E, Peacock J, Victor C, Thakar R, Manyonda I. Women's sexual health after childbirth. BJOG: an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology 2000;107:186‐95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bek 1992

- Bek KM, Laurberg S. Risks of anal incontinence from subsequent vaginal delivery after a complete obstetric anal sphincter tear. BJOG: an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology 1992;99:724‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Brown 2000

- Brown S, Lumley J. Physical health problems after childbirth and maternal depression at six to seven months postpartum. BJOG: an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology 2000;107:1194‐201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Buhling 2006

- Buhling KJ, Schmidt S, Robinson JN, Klapp C, Siebert G, Dudenhausen JW. Rate of dyspareunia after delivery in primiparae according to mode of delivery. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology 2006;124:42‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Dandolu 2005

- Dandolu V, Gaughan J, Chatwani A, Harmanli O, Mabine B, Hernandez E. Risk of recurrence of anal sphincter lacerations. Obstetrics and Gynecology 2005;105:831‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

de Leeuw 2007

- Leeuw JW, Wit C, Kuijken J, Bruinse HW. Mediolateral episiotomy reduces the risk for anal sphincter injury during operative vaginal delivery. BJOG: an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology 2007;115:104‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Edozien 2014

- Edozien LC, Gurol‐Urganci I, Cromwell DA, Adams EJ, Richmond DH, Mahmood TA, et al. Impact of third‐ and fourth‐degree perineal tears at first birth on subsequent pregnancy outcomes: a cohort study. BJOG: an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology 2014 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed]

Fenner 2003

- Fenner DE, Genberg B, Brahma P, Marek L, DeLancey JO. Fecal and urinary incontinence after vaginal delivery with anal sphincter disruption in an obstetrics unit in the United States. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2003;189:1543‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Fernando 2006

- Fernando RJ, Sultan AHH, Kettle C, Thakar R, Radley S. Methods of repair for obstetric anal sphincter injury. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2006, Issue 3. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD002866.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Fizgerald 2007

- Fitzgerald MP, Weber AM, Howden N, Cundiff GW, Brown MBP, for the Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Risk factors for anal sphincter tear during vaginal delivery. Obstetrics and Gynecology 2007;109:29‐34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Fornell 2005

- Fornell EU, Matthiesen L, Sjödahl R, Berg G. Obstetric anal sphincter injury ten years after: subjective and objective long term effects. BJOG: an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology 2005;112:312‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Fynes 1998

- Fynes M, Donnelly V, O'Connell PR, O'Herlihy C. Cesarean delivery and anal sphincter injury. Obstetrics and Gynecology 1998;92(4 Pt 1):496‐500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gurol‐Urganci 2013

- Gurol‐Urganci I, Cromwell DA, Edozien LC, Mahmood TA, Adams EJ, Richmond DH, et al. Third‐ and fourth‐degree perineal tears among primiparous women in England between 2000 and 2012: time trends and risk factors. BJOG: an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology 2013;120:1516‐25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Harkin 2003

- Harkin R, Fitzpatrick M, O’Connell PR, O’Herlihy C. Anal sphincter disruption at vaginal delivery: is recurrence predictable?. European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Biology 2003;109:149‐52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2011

- Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from www.cochrane‐handbook.org.

Hirayama 2012

- Hirayama F, Koyanagi A, Mori R, Zhang J, Souza JP, Gülmezoglu AM. Prevalence and risk factors for third‐ and fourth‐degree perineal lacerations during vaginal delivery: a multi‐country study. BJOG: an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology 2012;119:340‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Jango 2012

- Jangö H, Langhoff‐Roos J, Rosthøj S, Sakse A. Risk factors of recurrent anal sphincter ruptures: a population‐based cohort study. BJOG: an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology 2012;119:1640‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kudish 2008

- Kudish B, Sokol RJ, Kruger M. Trends in major modifiable risk factors for severe perineal trauma, 1996–2006. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics 2008;102:165‐70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Laine 2009

- Laine K, Gissler M, Pirhonen J. Changing incidence of anal sphincter tears in four Nordic countries through the last decades. European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Biology 2009;146:71‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Laine 2011

- Laine K, Skjeldestad FE, Sanda B, Horne H, Spydslaug A, Staff AC. Prevalence and risk factors for anal incontinence after obstetric anal sphincter rupture. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica 2011;90:319‐24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lowder 2007

- Lowder JL, Burrows LJ, Krohn MA, Weber AM. Risk factors for primary and subsequent anal sphincter lacerations: a comparison of cohorts by parity and prior mode of delivery. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2007;196:344.e1‐344.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

MacArthur 1997

- MacArthur C, Bick DE, Keighley MRB. Faecal incontinence after childbirth. BJOG: an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology 1997;104:46‐50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Macarthur 2004

- Macarthur AJ, Macarthur C. Incidence, severity, and determinants of perineal pain after vaginal delivery: a prospective cohort study. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2004;191:1199‐204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

McCandlish 1998

- McCandlish R, Bowler U, Asten H, Berridge G, Winter C, Sames L, et al. A randomised controlled trial of care of the perineum during second stage of normal labour. BJOG: an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology 1998;105:1262‐72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

McLeod 2003

- McLeod NL, Gilmour DT, Joseph KS, Farrell SA, Luther ER. Trends in major risk factors for anal sphincter lacerations: a 10‐year study. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada 2003;7:586‐93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Miner 1990

- Miner PB, Donnelly TC, Read NW. Investigation of mode of action of biofeedback in treatment of fecal incontinence. Digestive Diseases and Sciences 1990;35(10):1291‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mowatt 2007

- Mowatt G, Glazener CMA, Jarrett M. Sacral nerve stimulation for faecal incontinence and constipation in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2007, Issue 3. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004464.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

NICE 2007

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Intrapartum care of healthy women and their babies during childbirth. National Collaborating Centre for Women’s and Children’s Health 2007.

Norton 2012

- Norton C, Cody JD. Biofeedback and/or sphincter exercises for the treatment of faecal incontinence in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012, Issue 7. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD002111.pub3] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Payne 1999

- Payne TN, Carey JC, Rayburn WF. Prior third‐ or fourth‐degree perineal tears and recurrence risks. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics 1999;64:55‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Peleg 1999

- Peleg D, Kennedy CM, Merrill D, Zlatnik FJ. Risk of repetition of a severe perineal laceration. Obstetrics and Gynecology 1999;93:1021‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Rathfisch 2010

- Rathfisch G, Dikencik BK, Kizilkaya Beji N, Comert N, Tekirdag AI, Kadioglu A. Effects of perineal trauma on postpartum sexual function. Journal of Advanced Nursing 2010;66(12):2640‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

RCOG 2007

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. The Management of Third and Fourth Degree Perineal Ttears. Green Top Guideline No 29. London: RCOG, 2007. [Google Scholar]

RevMan 2014 [Computer program]

- The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration. Review Manager (RevMan). Version 5.3. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014.

Richter 2006

- Richter HE, Fielding JR, Bradley CS, Handa VL, Fine P, Fitzgerald MP, et al. Endoanal ultrasound findings and fecal incontinence symptoms in women with and without recognized anal sphincter tears. Obstetrics and Gynecology 2006;108:1394‐401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Stafne 2012

- Stafne SN, Salvesen KÅ, Romundstad PR, Torjusen IH, Mørkved S. Does regular exercise including pelvic floor muscle training prevent urinary and anal incontinence during pregnancy? A randomised controlled trial. BJOG: an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology 2012;119(10):1270‐80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sultan 1993

- Sultan AH, Kamm MA, Hudson CN, Thomas JM, Bartram CI. Anal‐sphincter disruption during vaginal delivery. New England Journal of Medicine 1993;329:1905‐11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sultan 1999

- Sultan AH. Obstetric perineal injury and anal incontinence. Clinical Risk 1999;5:193‐6. [Google Scholar]

Wheeler 2011

- Wheeler J, Davis D, Fry M, Brodie P, Homer CSE. Is Asian ethnicity an independent risk factor for severe perineal trauma in childbirth? A systematic review of the literature. Women and Birth 2011;25:107‐13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Williams 2005

- Williams A, Tincello DG, White S, Adams EJ, Alfirevic Z, Richmond DH. Risk scoring system for prediction of obstetric anal sphincter injury. BJOG: an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology 2005;112:1066‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]