Abstract

Long-standing cultural, economic, and political relationships among Benin, Nigeria, and Togo contribute to the complexity of their cross-border connectivity. The associated human movement increases the risk of international spread of communicable disease. The Benin and Togo ministries of health and the Nigeria Centre for Disease Control, in collaboration with the Abidjan Lagos Corridor Organization (a 5-country intergovernmental organization) and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, sought to minimize the risk of cross-border outbreaks by defining and implementing procedures for binational and multinational public health collaboration. Through 2 multinational meetings, regular district-level binational meetings, and fieldwork to characterize population movement and connectivity patterns, the countries improved cross-border public health coordination. Across 3 sequential cross-border Lassa fever outbreaks identified in Benin or Togo between February 2017 and March 2019, the 3 countries improved their collection and sharing of patients’ cross-border travel histories, shortened the time between case identification and cross-border information sharing, and streamlined multinational coordination during response efforts. Notably, they refined collaborative efforts using lessons learned from the January to March 2018 Benin outbreak, which had a 100% case fatality rate among the 5 laboratory-confirmed cases, 3 of whom migrated from Nigeria across porous borders when ill. Aligning countries’ expectations for sharing public health information would assist in reducing the international spread of communicable diseases by facilitating coordinated preparedness and responses strategies. Additionally, these binational and multinational strategies could be made more effective by tailoring them to the unique cultural connections and population movement patterns in the region.

Keywords: Epidemic management/response, Surveillance, International collaboration, Lassa fever

West Africa has a mobile and interconnected population, with common and complex cross-border movement.1 This human movement inherently increases the risk of the international spread of disease, as evidenced by the West Africa Ebola epidemic of 2014–2016 and repeated international cholera and Lassa fever outbreaks.2–4 Limiting the geographic spread of disease within a country requires comprehensive public health practice, including sensitive disease surveillance systems, timely and thorough outbreak response measures, and adequate staffing and infrastructure, with good communication across all participating agencies. Preparing for and responding to the international spread of disease has the added complexity of requiring information sharing and coordination between 2 or more unrelated public health systems, each with unique methods, staffing, and infrastructure.

With a guiding principle to mitigate the international spread of disease, the International Health Regulations (IHR 2005) provide legally binding guidance to all 196 member states, requiring that they share information about priority public health events with the World Health Organization (WHO) through their country’s IHR National Focal Point and recommending they share this information also with neighboring countries.5 In addition to the IHR reporting mechanism, intergovernmental bodies and regional disease surveillance networks around the world facilitate public health information sharing and coordination in smaller groups of neighboring countries.6,7 For example, the 15-country Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) published formal regulations in 2015 to support regional information sharing.8 Collectively, these regulations and networks facilitate global and multinational situational awareness and public health resource allocation for preparedness and response.

Concurrent with the global and ECOWAS efforts to share public health information on communicable disease events, the Benin and Togo ministries of health and the Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (NCDC), in collaboration with the Abidjan Lagos Corridor Organization (ALCO, an intergovernmental organization among Benin, Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Nigeria, and Togo) and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Division of Global Migration and Quarantine, initiated efforts in 2016 to strengthen cross-border collaboration. We describe here the process of refining public health collaboration among Benin, Nigeria, and Togo through lessons learned and successes from 3 sequential Lassa fever outbreaks identified in Benin and Togo from 2017 to 2019, each with cross-border elements.

Formalizing Cross-Border Collaboration

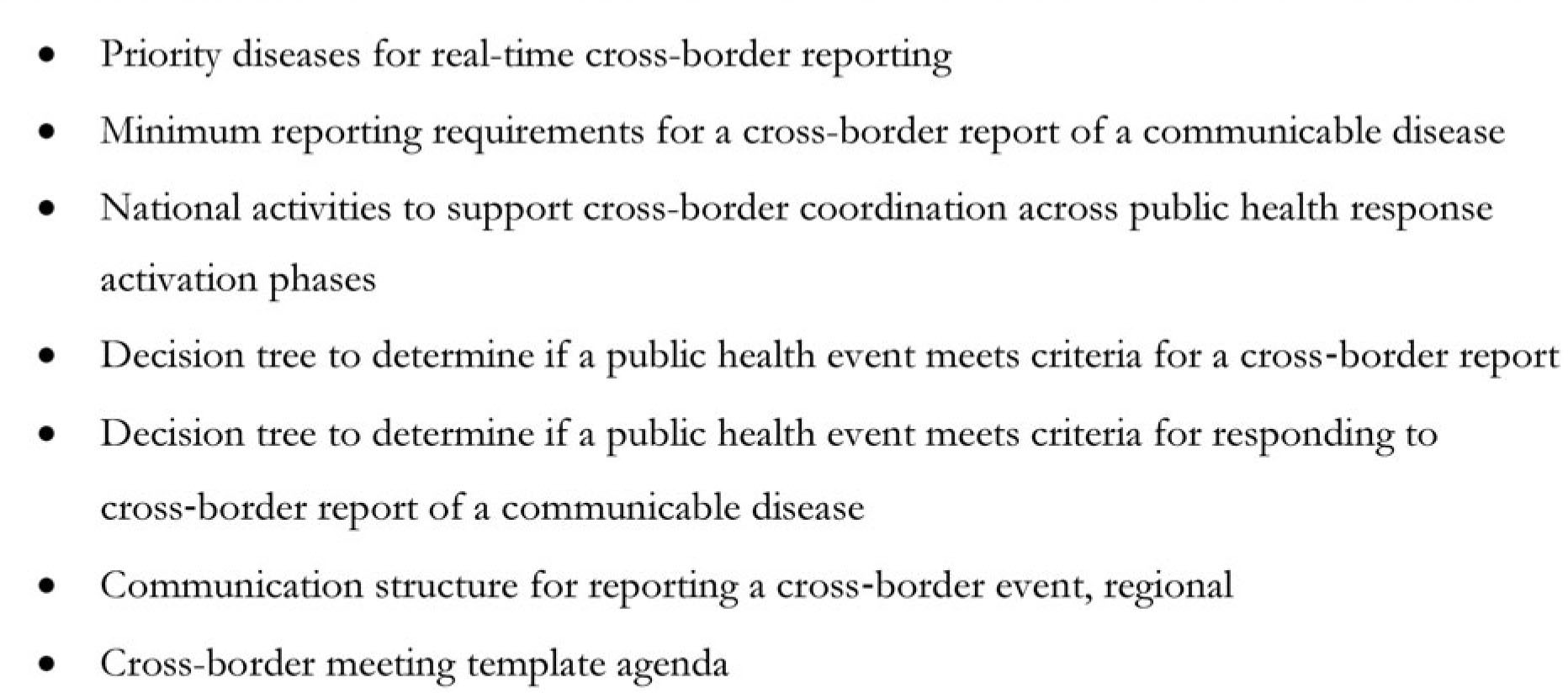

Multisectoral delegations from Benin, Ghana (district-level only), Nigeria, and Togo gathered in Cotonou, Benin, in December 2016 to draft a memorandum of understanding (MOU) and 7 supporting standard operating procedures (SOPs) to operationalize cross-border public health information sharing and collaboration using a One Health approach (Figure 1).9 At this meeting, public health surveillance and response leaders, country IHR National Focal Points, animal health representatives, ministry of health legal representatives, and others worked through case studies in country-specific groups to clarify priorities for what, when, and how to share public health information and when and how to respond after receiving a cross-border report. Group discussions led to a draft of shared expectations for each topic that embraced the unique design of each national public health system.

Figure 1.

Standard Operating Procedures Included in a Draft Memorandum of Understanding for Cross-Border Information Sharing and Collaboration Among Benin, Nigeria, and Togo, December 2016

Population Connectivity Across Borders

Additionally, Togo and Benin facilitated discussions about targeting strategies to address seasonal cross-border population movement across the highly populated coastal region. They used results from implementing the Population Connectivity Across Borders (PopCAB) method, a CDC-developed tool kit designed to engage multisectoral stakeholders at national, intermediate, and community levels in focus group discussions with participatory mapping.9 A PopCAB implementation team can analyze and create a visual representation of the gathered information to tailor public health surveillance, preparedness, and response efforts as well as cross-border collaboration strategies that respond to population mobility dynamics. More specifically, Togo and Benin presented results from PopCAB fieldwork among coastal fishermen and transporters, small entrepreneurs, and healthcare staff along the highway from Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, to Lagos, Nigeria. Finally, Benin, Nigeria, and Togo (and eventually Cameroon) initiated an analytic project designed to harmonize historical national cholera surveillance data to design more informed crossborder preparedness and response strategies.10

Application

On February 11, 2017, health facility staff at a district hospital in Benin performed an emergency cesarean section on a very ill patient who had just arrived from Nigeria. The doctor suspected she had Lassa fever and collected a blood sample for analysis at the national laboratory. The mother died soon after the delivery, but the newborn survived. On February 14, 2017, the deceased patient’s husband departed with the newborn, against medical advice and before the staff could gather his contact information. Later that day, laboratory analysis confirmed the deceased patient had had Lassa fever.

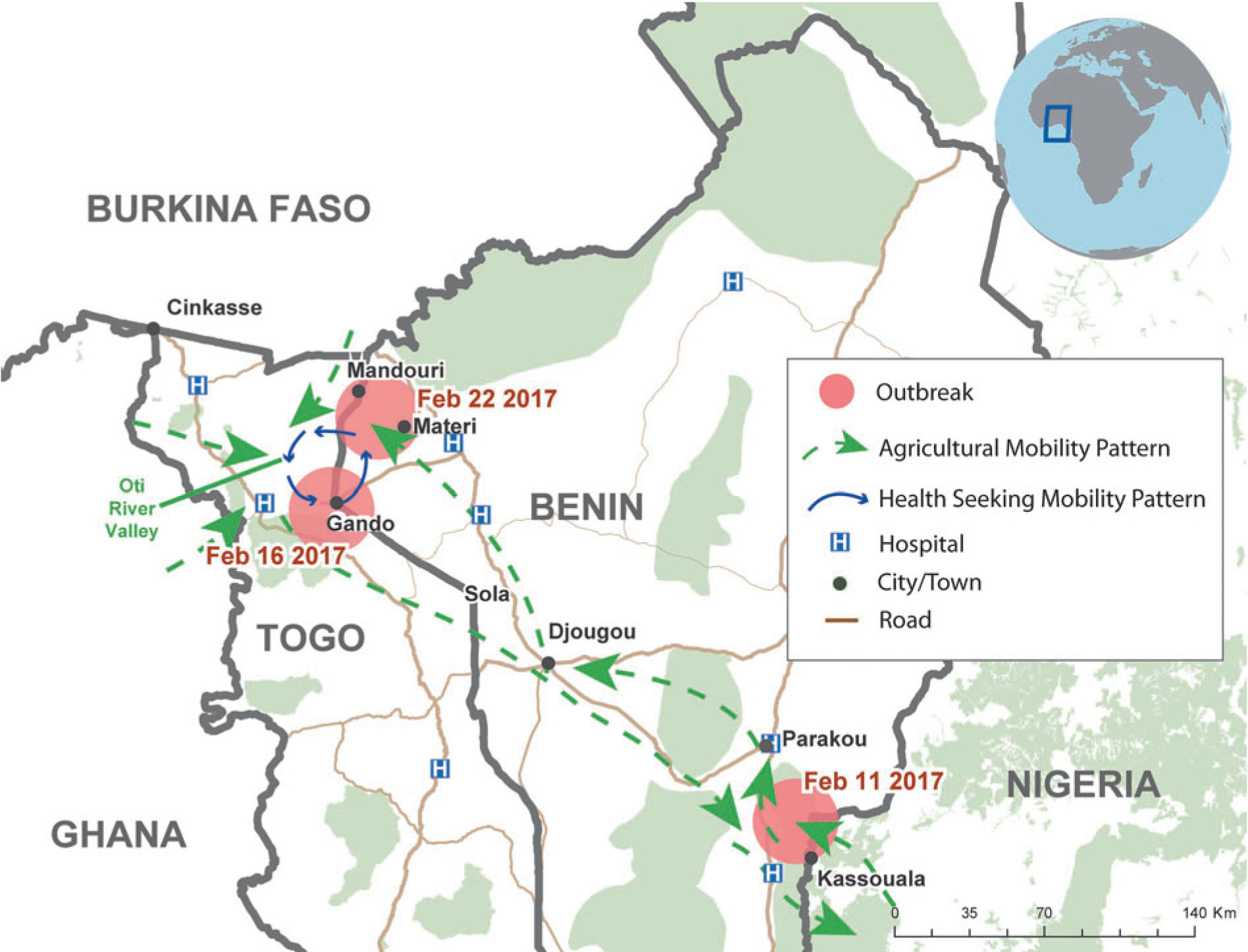

The only information the Benin IHR National Focal Point had about the deceased patient and her husband was that they were originally from Togo but had been living as agricultural migrants in Nigeria along the border with Benin. Typically, the IHR National Focal Point would activate a nationwide search to promptly locate the husband and baby to provide medical follow-up and avoid spread of infection. However, the Benin Ministry of Health had recently participated in multisectoral, binational meetings with Togo that included a PopCAB-based exercise to elicit information on informal migration pathways and points of interest within and across their national borders. One of the migration patterns that emerged was the circular migration route traveled by seasonal migrants from Togo and Benin seeking agricultural opportunities in Nigeria (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Map of circular migration route among Benin, Nigeria, and Togo with locations of Lassa fever cases from February 2017.

With the limited available demographic and travel history data about the father and newborn and the information about the circular migration pathway, the Benin IHR National Focal Point rapidly contacted his counterpart in Togo, district surveillance leads in Benin all along the relevant circular migration route, and the WHO office in Benin for a joint active search of high-risk Lassa fever contacts. With this collaborative effort, the father and newborn were located in a village on the Togolese side of a cross-border community, before they sought formal health care. The newborn later tested positive for Lassa fever and received treatment but died 10 days later. No other secondary case was identified.

A few days later, on February 22, the Benin Ministry of Health identified a second, unrelated Lassa fever case at a medical facility along the migration route. Medical staff were extra vigilant as a result of targeted risk communication along the migration pathway. They rapidly identified and successfully managed the case, preventing further transmission.

Unlike previous outbreaks, there was a coordinated community-level response between Benin and Togo, which contributed to preventing secondary cases. This highlighted the value of improved knowledge about population migration and community connectivity; having such awareness enables targeted response initiatives and efficient crossborder information sharing and response coordination in accordance with procedures in the draft MOU and supporting SOPs.

Refining SOPs and Communication Mechanisms

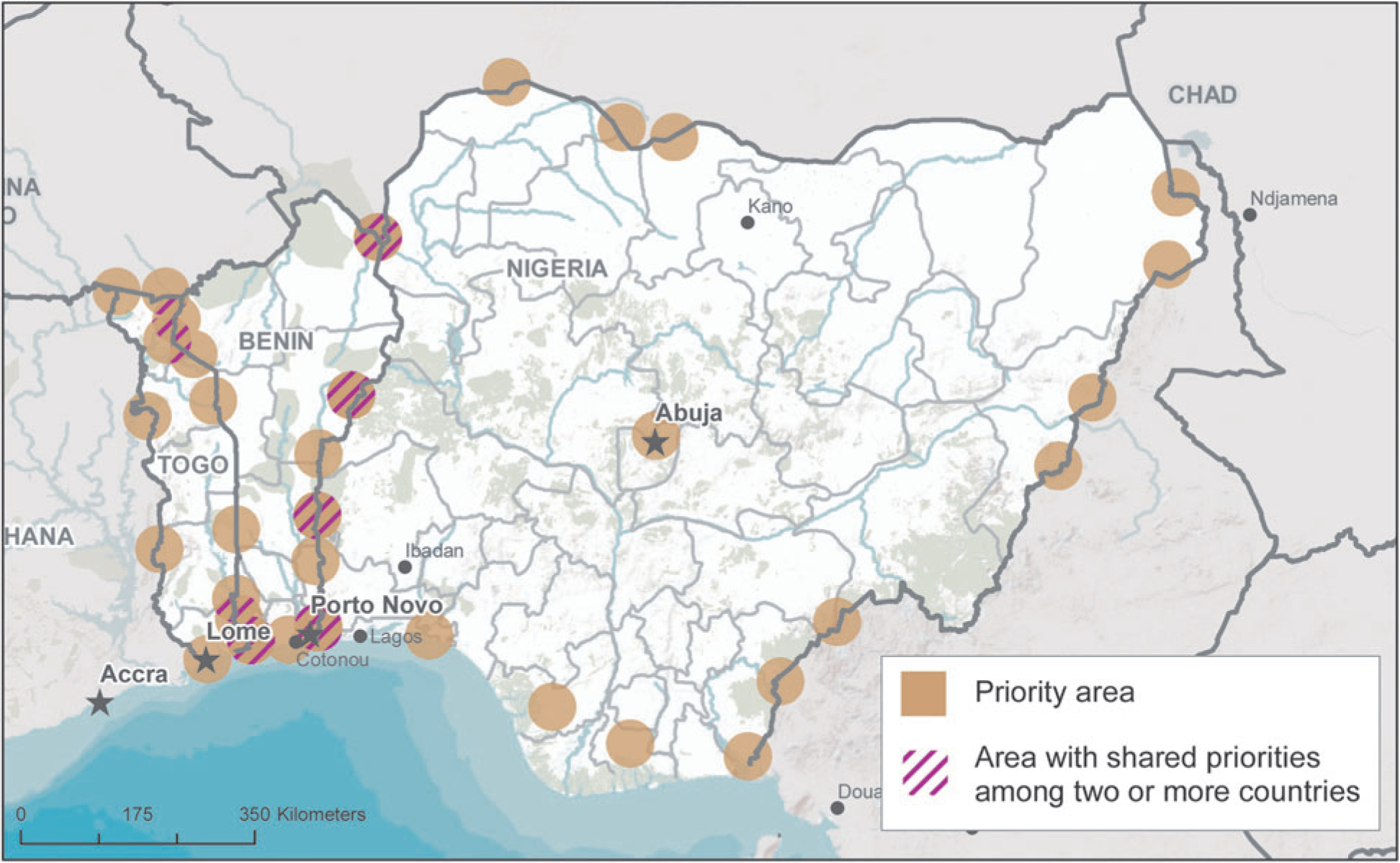

In reviewing their response, the Benin and Togo ministries of health identified the need to improve collection, analysis, and sharing of detailed travel histories, especially for cross-border travel. They conveyed their feedback during the multinational meeting in August 2017 in Lomé, Togo. During this meeting, Benin, Ghana, Togo, and Nigeria, with the addition of Côte d’Ivoire, updated the MOU and refined the 7 supporting SOPs. They also completed a 5-country bilingual (French and English) tabletop exercise to evaluate expectations for cross-border collaboration. Additionally, participants identified geographic border zones with binational concordance for prioritizing cross-border efforts (Figure 3). Finally, the delegates established a “WhatsApp” group to facilitate exchanging public health updates. These efforts further formalized the cross-border collaboration occurring through routine, district-level crossborder meetings among Benin, Ghana, Nigeria, and Togo.

Figure 3.

Multinational map of priority border areas created in August 2017 (contributions from Benin, Nigeria, and Togo extracted from full 5-country map).

Application

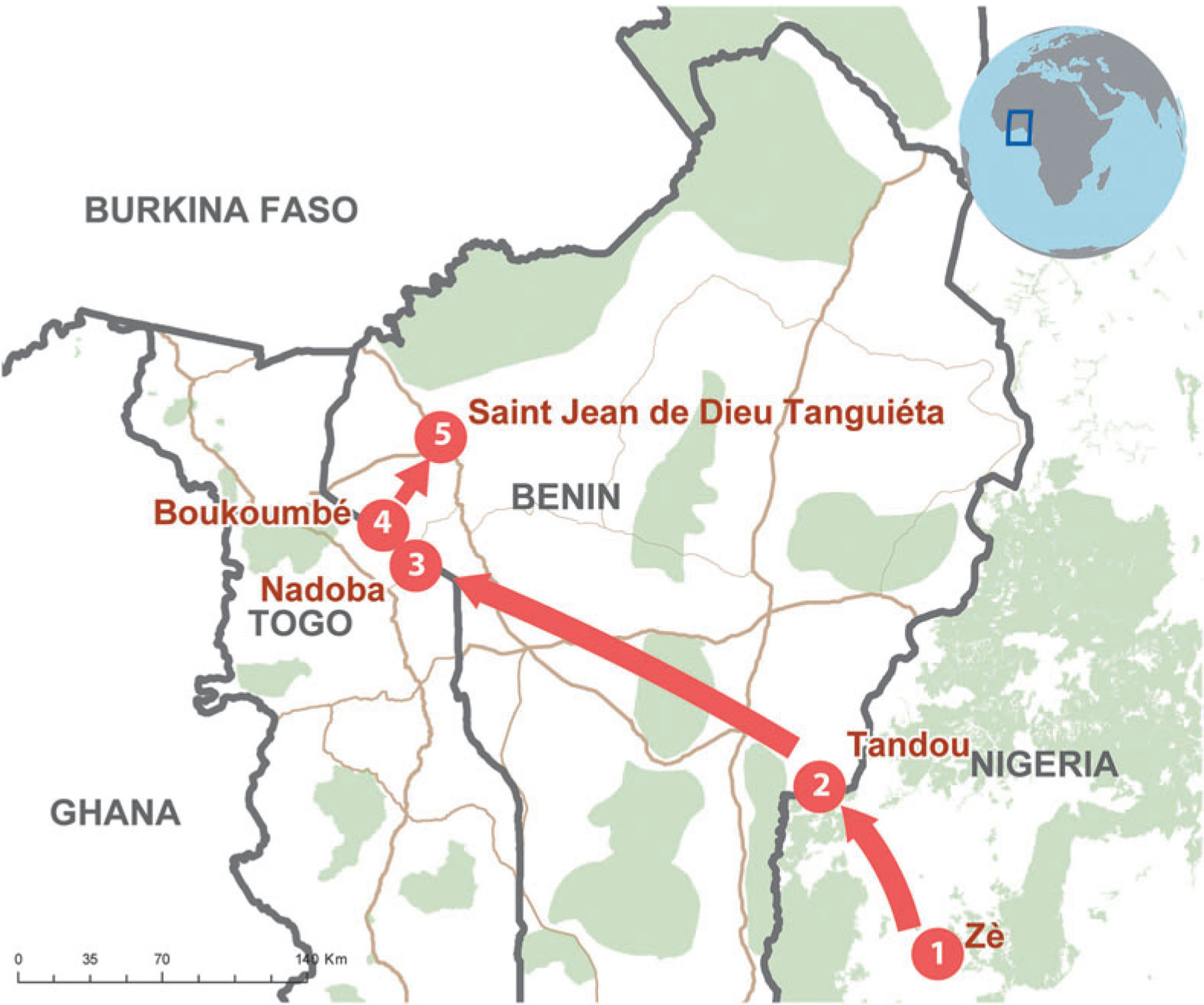

On January 8, 2018, the Benin Ministry of Health documented its first Lassa fever case of the year at a district hospital in Tanguiéta. With increased emphasis on gathering thorough travel history information, public health staff documented from the index patient a complex movement pattern beginning with illness onset in Ze, Nigeria, followed by travel through Benin to Nadoba, Togo, before diagnosis in Boukombe, Benin, and treatment at a referral hospital in Tanguiéta (Figure 4). Contact tracing identified 55 contacts in 19 health facilities and 36 communities in Benin and Togo. By the end of January, Benin had identified 5 laboratory-confirmed Lassa fever cases out of 20 investigated cases.

Figure 4.

Three-country travel history for index case in January to March 2018 Lassa fever outbreak in Benin.

As the outbreak grew, the Benin IHR National Focal Point followed the multinational SOPs and notified his counterpart at the NCDC on February 25, 2018, of the Lassa fever cases in Benin imported from Nigeria via land travel. The NCDC immediately activated a response and deployed 2 rapid response teams to Kwara State and the Saki area in Oyo State. The rapid response teams identified 97 communities along the Benin-Nigeria border with possible exposures and 340 case contacts, including 47 identified at health facilities. Educational materials on Lassa fever were shared with the communities. All contacts were followed for symptom onset, but none developed illness.

By the close of the outbreak on March 5, 2018, Benin had investigated 24 cases (5 laboratory-confirmed, 3 probable, and 16 suspected). The first 3 of the 5 confirmed cases traveled to Benin from Nigeria. The last 2 confirmed cases were domestic and diagnosed in 2 separate areas along Benin’s border with Nigeria. No epidemiologic link was identified among the 5 cases. All 5 laboratory-confirmed cases in Benin died (100% case fatality ratio, or CFR). By March 4, 2018, Nigeria had recorded 353 confirmed cases, with 78 deaths among confirmed cases (22.1% CFR).11

Improving Data Collection and Management Strategies

During this outbreak, Benin showed an improved capacity to collect and disseminate detailed, cross-border travel histories and associated risk assessments. Collectively, Benin, Nigeria, and Togo rapidly targeted cross-border collaboration while sustaining ongoing, routine communication. After the outbreak concluded in Benin, the countries identified some likely causes of the unexpected 100% CFR among laboratory-confirmed cases in Benin, a country with sufficient capacity to provide supportive care and antiviral treatment with ribavirin: poor access to care for cross-border travelers and migrants due to prohibitive cost, language barriers, perceived stigma by healthcare providers, the consequent time required to travel home from distant communities for care after illness onset, and a predominant cultural preference to seek treatment first from traditional healers.12

In April 2018, the Benin and Togo ministries of health, in collaboration with ALCO and CDC, conducted Pop-CAB training workshops, including fieldwork, for national, regional, and district staff in the northern area of their countries to characterize cross-border population movement and connectivity across Benin, western Nigeria, and Togo. They tailored PopCAB fieldwork to additionally describe healthcare provider networks and catchment areas. Within 8 days, the collaborators trained 54 staff across Benin and Togo, who subsequently implemented 21 PopCAB events across 14 cities with 224 community members representing 7 stakeholder groups: border officials, community members, community leaders, migrants, traditional healers, transporters, and health center staff.

In December 2018, Benin, Nigeria, and Togo met again in Cotonou, Benin, to improve national preparedness and response strategies as well as to continue refining cross-border strategies, especially those specific to Lassa fever. They used the recent PopCAB results to target communities for improved surveillance training and cross-border collaboration support. Additionally, Benin and Togo delegates discussed how they integrate PopCAB in national and district communicable disease outbreak preparedness and response plans to more efficiently address population movement in risk assessments and resource allocation efforts.

Application

On December 7, 2018, the final day of the 3-country meeting in Cotonou, the Benin Ministry of Health registered the first laboratory-confirmed case of Lassa fever in the second outbreak of the disease that year. The patient was a Beninois woman living in Kwara State, Nigeria, on the Benin-Nigeria border. Similar to the first outbreak in 2018, Benin Ministry of Health epidemiologists completed a detailed investigation of the index case. Additionally, the Benin IHR National Focal Point immediately informed counterparts in the NCDC and Togo Ministry of Health, as agreed during the cross-border collaboration meetings.

In response, NCDC sent a rapid response team in December 2018 to Kwara state for a 1-month active case search in communities and health facilities along the Benin border. During its search efforts, the team also taught healthcare workers how to detect, prevent, and manage Lassa fever and distributed education and communication materials to communities and healthcare facilities in the priority geographic area. No cases suggestive of Lassa fever were found during the retrospective and prospective case searches in Kwara state. This NCDC effort, conducted in collaboration with the Benin Ministry of Health, reflected the most timely cross-border collaborative response to date, as the activities occurred early in the outbreak.

On January 2, 2019, medical staff in Doufelgou district, Togo, identified a suspected case and immediately isolated and treated the patient until he died on January 8. This initial case was a 20-year-old Togolese man who had been living as an agricultural migrant for 1 year in Ogun state, Nigeria, along the Benin border. There were no secondary cases among the 33 identified contacts. Subsequently, on January 10, surveillance staff identified a probable case in the Centrale Region of Togo. The patient had recently returned to her home in Sokode, Togo, after living and working as a migrant in Lagos, Nigeria. The Togo Ministry of Health followed all 44 identified contacts, none of whom became ill with Lassa fever.

By March 29, 2019, the Benin Ministry of Health had investigated a total 25 cases (9 laboratory-confirmed, 1 probable, and 15 suspected). For each, the Benin Ministry of Health documented detailed travel history information. Six of the 9 confirmed cases were in individuals who migrated to Benin from Nigeria after illness onset, between December 2018 and January 2019. The Benin Ministry of Health identified epidemiologic links among those 6 patients, who belonged to 2 closely related families. The 3 other confirmed cases, an isolated case in Cotonou and infections in a father and son in Tchaourou along the border with Nigeria, were domestic. There was no epidemiologic link between the 2 clusters. Of note, 6 of the laboratory-confirmed cases were identified through follow-up among the 80 contacts. With the commitment and effort by the Ministry of Health to learn from experience by engaging with cross-border counterparts, quickly identifying and responding to travel and exposure histories, and rapidly engaging community members and multiple stakeholder groups, the 9 confirmed cases were identified early enough to provide adequate treatment, and none died.

Throughout these simultaneous outbreak investigations, all 3 countries continued to communicate regularly during biweekly conference calls and through the WhatsApp group about the epidemiologic situation and response efforts.

Discussion

Through 3 successive Lassa fever outbreaks in Benin and Togo, each with cross-border implications, Benin, Nigeria, and Togo enhanced their binational and multinational communication and collaboration to rapidly identify and respond to cases and at-risk communities connected through informal migration and cultural, economic, and political relationships. They accomplished this goal by improving travel history assessments and focusing on tailored risk forecasting and response strategies that integrated community-level information on population movement and community connectivity patterns. Further, they aligned expectations, harmonized across distinct public health systems, and refined when, what, and how to share and respond to public health information.

In the January to March 2018 outbreak, Benin recorded an alarming 100% CFR among the 5 laboratory-confirmed Lassa fever cases despite the availability of the antiviral drug ribavirin.13 All 5 patients presented at formal healthcare facilities in an advanced stage of disease, when treatment is likely to be less effective, and died within 1 or 2 days of arriving. Similarly, the treatment for the newborn with Lassa identified in the community in Togo was also unsuccessful, possibly because the intervention was initiated many days after birth. The delayed presentation at equipped formal healthcare facilities is associated with 3 main factors linked to population movement and community connectivity across borders and wide geographic areas. This context requires public health practitioners to think creatively about how to engage additional sectors, including mobile populations, informal migrants, and traditional healers, in public health surveillance, preparedness, response, and education campaigns and to change public health policies and practices to improve healthcare access for these groups.14

In a global context of high-volume cross-border population movement and community connectivity, coordinating public health information multinationally is challenging. The examples in this article highlight the value of adapting public health systems to informal migration pathways, cross-border movement patterns, and other cultural factors that influence who moves from one place to another and where, when, why, and how they move. Taken together, these collaborative initiatives must engage a comprehensive, multisectoral border health system approach to remain nimble and responsive to dynamic cross-border environments. These approaches are highly effective at facilitating cross-border outbreak response in the absence of formal, regional, real-time data management systems.

While public health practitioners develop binational and multinational information management systems and dashboards, we must continue to establish and refine operational guidelines to prevent cross-border communicable disease outbreaks. When successful, multinational public health coordination can minimize delayed detection of and increase effective response to communicable disease threats. Ultimately, in our globally mobile world, public health practitioners can contribute to global health security and the IHR (2005) mandate to lessen the international spread of communicable disease by cultivating rapid and effective public health information sharing and collaboration across borders. These coordinated efforts should respond to unique dynamics of cross-border community connectivity, population mobility patterns, and healthcare-seeking behaviors while accommodating disparate national and local public health systems and infrastructure.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the World Health Organization in Benin for their continued support. We thank the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the US Agency for International Development (USAID) Benin for financially supporting fieldwork, multinational meetings, and outbreak response efforts. We acknowledge Elvira McIntyre, who developed spatial databases and maps for PopCAB activities, and Kevin Griffee for his support to the Benin Ministry of Health with managing travel history information for the January to March 2018 Lassa fever outbreak.

Contributor Information

Clement Glèlè Kakaī, National Directorate of Public Health, Ministry of Health, Cotonou, Benin.

Oyeladun Funmi Okunromade, Department of Surveillance and Epidemiology;.

Chioma Cindy Dan-Nwafor, Department of Surveillance;.

Ali Imorou Bah Chabi, Abidjan Lagos Corridor Organization, Cotonou, Benin.

Godjedo Togbemabou Primous Martial, National Directorate of Public Health, Ministry of Health, Cotonou, Benin.

Mahmood Muazu Dalhat, African Field Epidemiology Network (AFENET) Nigeria, Abuja, Federal Capital Territory, Nigeria.

Sarah Ward, Division of Global Migration and Quarantine, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA.

Ouyi Tante, National Cholera Officer and Other Diarrheal Diseases, Division of Disease Control;.

Patrick Mboya Nguku, African Field Epidemiology Network (AFENET) Nigeria, Abuja, Federal Capital Territory, Nigeria.

Assane Hamadi, Division of Disease Control; all in the Ministry of Health, Lomé, Togo.

Elsie Ilori, Department of Surveillance;.

Virgil Lokossou, West Africa Health Organization, Bobo Dioulasso, Burkina Faso.

Carlos Brito, West Africa Health Organization, Bobo Dioulasso, Burkina Faso.

Olubunmi Eyitayo Ojo, Nigeria Centre for Disease Control, Federal Ministry of Health, Abuja, Nigeria.

Idrissa Kone, Abidjan Lagos Corridor Organization, Cotonou, Benin.

Tamekloe Tsidi Agbeko, Ministry of Health, Lomé, Togo.

Chikwe Ihekweazu, Nigeria Centre for Disease Control, Federal Ministry of Health, Abuja, Nigeria.

Rebecca D. Merrill, Division of Global Migration and Quarantine, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA.

References

- 1.Charrière F, Frésia M. West Africa as a Migration and Protection Area. UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR); 2008. https://www.unhcr.org/49e479c311.pdf. Accessed December 10, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dudas G, Carvalho LM, Bedford T, et al. Virus genomes reveal factors that spread and sustained the Ebola epidemic. Nature 2017;544(7650):309–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.UNICEF/WHO. UN agencies warn that cholera epidemic is spreading in West Africa. ReliefWeb September 5, 2012. https://reliefweb.int/report/sierra-leone/un-agencies-warn-cholera-epidemic-spreading-west-africa. Accessed December 10, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kofman A, Choi MJ, Rollin PE. Lassa fever in travelers from West Africa, 1969–2016. Emerg Infect Dis 2019;25(2):245–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. International Health Regulations (2005). 3d ed. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lawpoolsri S, Kaewkungwal J, Khamsiriwatchara A, et al. Data quality and timeliness of outbreak reporting system among countries in Greater Mekong subregion: challenges for international data sharing. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2018; 12(4):e0006425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ope M, Sonoiya S, Kariuki J, et al. Regional initiatives in support of surveillance in East Africa: the East Africa Integrated Disease Surveillance Network (EAIDSNet) experience. Emerg Health Threats J 2013;6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Economic Community of West African States. Establishing a network for epidemiological surveillance and communicable disease control across the ECOWAS region. In: Regulations c/reg 41/12/15 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Merrill RD, Rogers K, Ward S, et al. Responding to communicable diseases in internationally mobile populations at points of entry and along porous borders, Nigeria, Benin, and Togo. Emerg Infect Dis 2017;23(Suppl):S114–S120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glele CK, Dalhat M, Valentin OT, et al. Improving crossborder and regional communicable disease surveillance and response through a novel multicountry collaboration, Togo, Benin, Nigeria, and Cameroon. Paper presented at: ASTMH 2018; October 28-November 1, 2018; New Orleans, Louisiana. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nigeria Centre for Disease Control. Situation Report: 2018 Lassa fever outbreak in Nigeria. Nigeria Centre for Disease Control; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Houlihan C, Behrens R. Lassa fever. BMJ 2017;358:j2986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Okunromade O, Glele CK, Dalhat MM, Merrill RD, Ojo O, Ihekweazu C. Cross-border travel and high case fatality of Lassa fever for outbreak in Benin Republic, December 2017-March 2018. Paper presented at: Global Health Security 2019; June 18–20, 2019; Sydney, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marano N, Angelo KM, Merrill RD, Cetron M. Expanding travel medicine in the 21st century to address the health needs of the world’s migrants. J Travel Med 2018;25(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]