Abstract

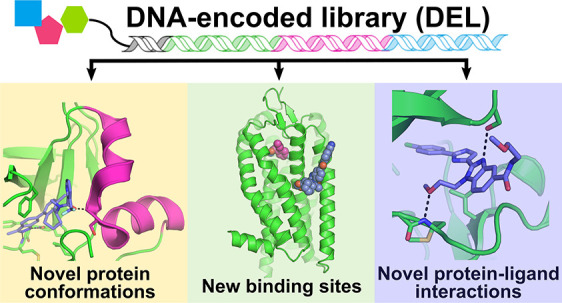

The DNA-encoded library (DEL) discovery platform has emerged as a powerful technology for hit identification in recent years. It has become one of the major parallel workstreams for small molecule drug discovery along with other strategies such as HTS and data mining. For many researchers working in the DEL field, it has become increasingly evident that many hits and leads discovered via DEL screening bind to target proteins with unique and unprecedented binding modes. This Perspective is our attempt to analyze reports of DEL screening with the purpose of providing a rigorous and useful account of the binding modes observed for DEL-derived ligands with a focus on binding mode novelty.

Significance

Screening DNA-encoded libraries (DELs) of small molecules has recently become one of the main technologies employed for discovering potential new drugs. Here, we analyze and discuss recent published DEL screens performed against important clinical molecular targets. Notable trends observed, including an apparent tendency for inhibitors from DEL screens to be highly selective and to adopt novel binding modes, are highlighted and discussed alongside the current state of the field and future considerations.

Introduction

Screening, the testing of molecule collections to discover compounds with a desired activity, remains the foundational discovery method in small molecule drug development. A study by Roche/Genentech found that, depending on the year, between one-quarter and one-half of prosecuted lead series were discovered by various types of screening.1 The remainder were mostly generated by knowledge-based or legacy approaches, e.g. “patent-busting”. High-throughput screening (HTS) was the most productive form of screening,2,3 accounting for the majority of screening-derived lead series in most years, while Focused Screening4,5 and Fragment Screening were also well-represented. DEL screening6,7 emerged as a source of leads in the last 5 years. Virtual approaches (labeled as “de novo” discovery in the publication) represented a relatively small fraction of the lead series (0–10% in most years). A recent analysis of published development candidates and screening hits reached similar conclusions, although DEL was underrepresented compared with the analysis above, not inconsistent with the typical hit-to-candidate timeline.8

Screening is often described as “exploring” the “chemical space”9,10 embodied in the molecule collection at hand. Chemical space is enormous; some estimates place the number of possible compounds with drug-like physicochemical properties to be as high as 1060. It is likely that the pharmacologically relevant space is smaller, due to some degree of conservation in the shape and volume of protein ligand binding sites.11 But even still, the space of potentially useful compounds is enormous and much too large to be effectively sampled using current screening methods. Contemporary Pharma HTS collections typically contain on the order of 1–3 million compounds, very much smaller than the potentially useful space indicated above. Therefore, deliberate choices must be made on which compounds to include (and exclude) from a screening deck.12,13 The precise selection criteria for building a screening collection varies from organization to organization.14−16 Concepts like privilege17 and diversity18 are balanced with developability properties, solubility, stability, synthetic tractability, and avoidance of nuisance compounds,19 to arrive at an organization’s desired screening deck. Due to the vastness of chemical space and our limited means of exploring it, all screening collections are the result of deliberate human decision-making.

DEL screening stands in contrast to other methods in that it is less influenced by human decision-making. There are virtually no limits to the number of building blocks that can be included within a given reaction scheme because the encoding capacity at each synthetic step is very much in excess of the number of commercially available building blocks in a particular reactivity class. Library size and diversity are therefore governed by the number of available building blocks, their reactivity, and one’s budget to acquire them.20 Fortunately, the scope and diversity of modern building block collections are sufficient to ensure that even simple schemes can give rise to diverse and useful compounds.21 If we define accessible chemical space as the totality of theoretical compounds that could be easily assembled from commercially available reagents, then DEL is the only approach that lets us meaningfully sample the accessible space. For more information about the practice and philosophy of DEL design, we refer the reader to a recent publication on this topic.22

Due to the arithmetic of combinatorial synthesis and the large number of available building blocks, DELs of immense numerical size can be constructed in just a few synthetic operations. To give a sense of the scale of DELs, we can consider the CAS registry. Compiled from the literature and patents from the last 100 years, its 275 million compounds represent the totality of the chemical enterprise. Beyond drug-like organic compounds, it also contains coordination compounds, alloys, polymers, and other substances of low interest in drug discovery. DELs containing over 275 million drug-like compounds are routinely synthesized. Therefore, a single DEL can survey more compounds than have ever been prepared and reported in the history of modern chemistry.

It is important to note that while numerical size is often used as shorthand for chemical diversity, the two are not equivalent. There is some evidence that DEL productivity does not correlate with library size.23 It is the opinion of the authors that the number and diversity of library building blocks, rather than overall library size, is the key determinant in the hit generating capacity of an individual DEL. Having access to many such DELs, with varying schemes, cores, and connection chemistries, is an important factor in overall success rates and is key to the varied molecular architectures embodied in the examples below.

What might be the consequence of screening such ultralarge and structurally unbiased libraries? If there were only a limited universe of potential ligand-protein interactions, then current HTS decks might cover that universe reasonably well. In such a world, where there are only limited ways for ligands to solve the problem of protein binding, DEL screening would be expected to yield hits of low novelty in terms of binding interactions. It seems intuitive, however, that with chemical space being so vast and our ability to mine it so sparse, there must be untapped opportunities in ligand-protein interactions. What benefit then could be derived from a broader exploration of chemical space?

The first benefit one might observe is the ability to successfully discover ligands to targets that have failed other hit identification methods. While there are cases of DEL screening enabling the “drugging of the undruggable”, including one discussed below, most are unpublished and thus beyond the view of this Perspective. But there is another consequence one could expect: the discovery of novel modes of ligand-protein interactions. If we are truly exploring novel and unexplored regions of chemical space, then we should be able to observe proteins responding in novel and unexplored ways.

There is now a critical mass of DEL publications that include structural data, in particular crystallography data, so that one could systematically probe this question. In this Perspective, we examine published DEL screening experiments and determine whether novel ligand-protein interactions are observed. Such novelty could be exemplified by novel binding sites (including allostery), novel binding modes or interactions in known sites, unusual protein conformation, or unprecedented modes of inhibition. We will examine selected DEL publications and assess the nature of their reported ligand-protein interactions in comparison to what has been reported before.

Proteins Adopting Novel Conformations

c-MET

c-MET (mesenchymal (to) epithelial transition factor, also known as hepatocyte growth factor receptor) is a receptor tyrosine kinase involved in the regulation of multiple key cellular processes, including growth, motility and survival.24 The dysregulation of this kinase is well-known to play a major role in many human cancers and as such, c-MET has received considerable attention as a drug target.25 Many small molecule inhibitors of c-MET have been disclosed and several have been approved for use in treating c-MET driven cancers.26,27 These inhibitors can broadly be divided into two classes–type I or type II – based on the mode by which they bind to c-MET. Approved type I inhibitors, including crizotinib, savolitinib, capmatinib, and tepotinib, are known or expected to bind to the ATP-binding site of c-MET and achieve extremely high selectivity by π-stacking onto a tyrosine residue (Y1230) located within the kinase’s A-loop (activation loop).28−30 Type II inhibitors, such as cabozantinib (approved) or foretinib (not currently approved), also bind to the ATP site, but in addition extend deeper into the active site, displacing the conserved “DFG” peptide motif of the A-loop.31 While type I inhibitors are proving effective, the emergence of acquired drug-resistant mutant forms of c-MET poses a major challenge,32−37 and there is currently a need for inhibitors able to inhibit both wild-type and drug-resistant mutant forms of the kinase, while maintaining high kinome selectivity.

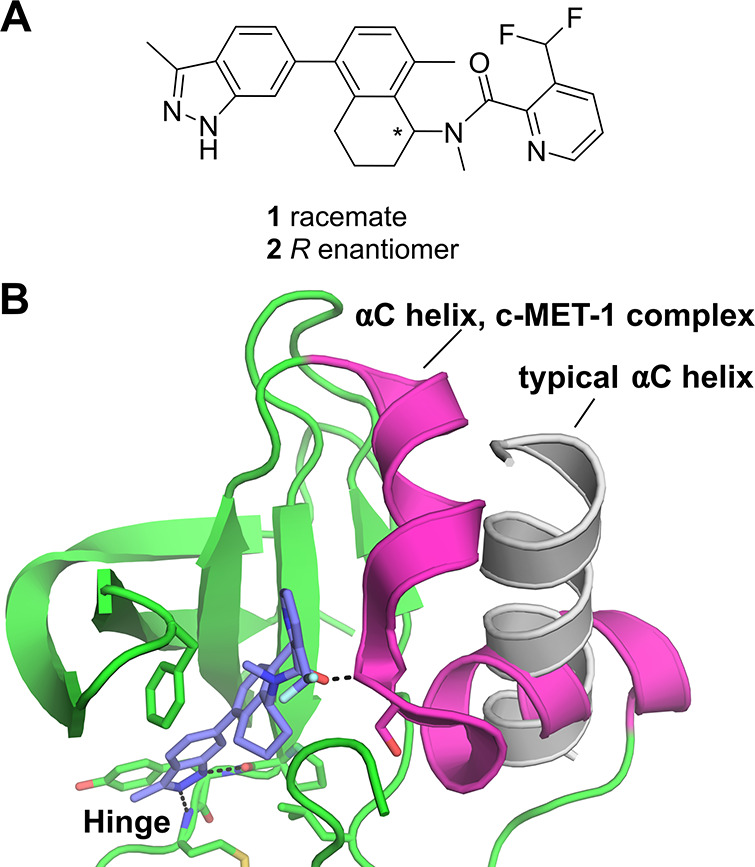

Toward this end, researchers at AstraZeneca, in collaboration with researchers at X-Chem, screened a DNA-encoded chemical library deck (ie a pooled collection of multiple DELs) composed of over 100 billion compounds against both wild-type and the acquired drug-resistant D1228V mutant form of c-MET.38 Following analysis of the screen output, racemic compound 1 was selected for off-DNA synthesis (Figure 1a), with subsequent SPR analysis confirming the compound to bind to c-MET. Crystallization experiments were then attempted (focusing on the D1228V mutant, for which 1 was seen to have a higher affinity), resulting in a 2.01 Å crystal structure (Figure 1b). Analysis of the crystal structure showed compound 1 to bind to the hinge region of the kinase and extend into the back pocket, superficially similar to the binding mode of a type II inhibitor. However, it was noted that the αC helix appeared to adopt a highly unusual conformation, having reordered to form two orthogonal helices (shown in magenta in Figure 1b), rather than the single helix typically seen for kinase αC helices (shown in light gray in Figure 1b). In order to investigate whether this αC helix conformation had been observed previously, a database containing over 8400 kinase crystal structures was searched using the c-MET-1 complex structure as a query. These efforts were unable to find a kinase crystal structure with a comparable αC helix conformation, suggesting that the kinase conformation observed in the c-MET-1 complex to be unique. The active enantiomer (as indicated by the crystal structure) was then isolated (yielding compound 2) and profiled further. When tested in an in vitro biochemical enzymatic assay, 2 was seen to inhibit wild-type and D1228V c-MET with IC50 values of 0.9 and 0.09 μM, respectively. Interestingly, an assessment of 2 for kinase selectivity against a panel of ∼140 kinases indicated this compound to be highly selective for c-MET, in line with the unusual binding mode observed crystallographically. This work therefore highlights the ability of DEL screening to discover inhibitors with not only novel binding modes but also with favorable pharmacological properties (such as high target selectivity).

Figure 1.

(a) Chemical structures of c-MET inhibitors 1 and 2 discovered by screening a DNA-encoded library deck against wild-type and the D1228V drug-resistant mutant form of c-MET reported by Collie et al.38 (b) Crystal structure of D1228V c-MET bound by compound 1 highlighting the highly unusual conformation of the αC helix (magenta, PDB entry 8ANS) observed in this complex. For comparison, in light gray is shown the αC helix from the crystal structure of c-MET bound by savolitinib (PDB entry 6SDE(28)), showing the typical conformation for this helix.

TAK1

TGF-β-activated kinase 1 (TAK1), also known as MAP3K7 and MEKK7, is a serine/threonine kinase involved in the regulation of innate and adaptive immune responses, neural fold morphogenesis, vascular development, and tumorigenesis.39 TAK1 can be activated by transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β),40 and facilitates downstream signaling of multiple pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, TLR ligands, LPS, and IL-1.41 TAK1 forms a stable complex with TAK1 binding protein 1 (TAB1), and triggers TAK1 kinase activity.42 The therapeutic potential of TAK1 inhibitors has been investigated for the treatment of pancreatic,43 ovarian,44 and breast45 cancers as well as inflammatory diseases.46

Several TAK1 inhibitors have been reported, including the natural product 5Z-7-oxozeaenol, an irreversible covalent inhibitor that binds to an active site cysteine residue of TAK1.47,48 The compound demonstrated cell activity; however, it lacks selectivity, as it binds many other kinases that possess a similar active site cysteine. More recent studies have described type I and type II kinase inhibitors such as takinib.49 These were identified from various screening campaigns, and the optimization of their potency was aided by structure-based drug design (SBDD). Despite tremendous effort, the right combination of kinase selectivity and cell potency was not achieved.

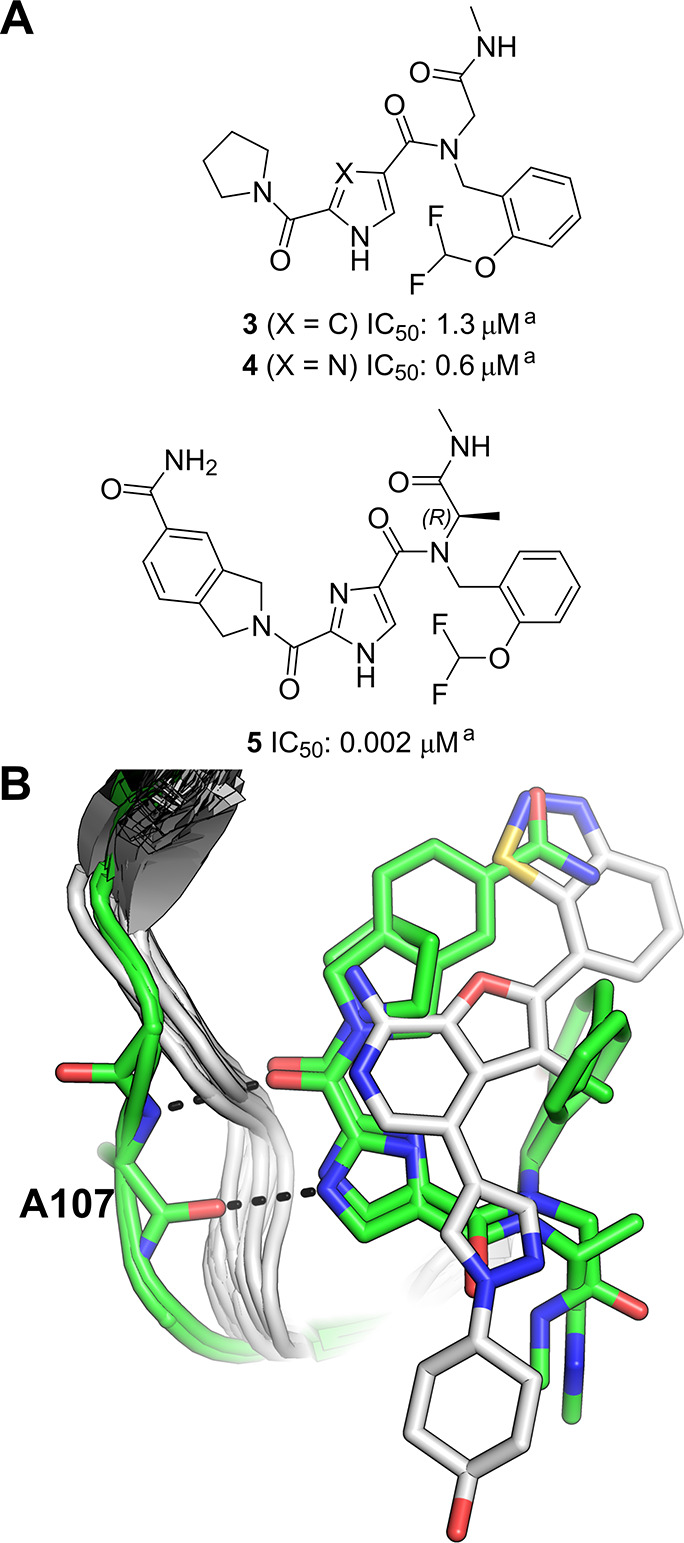

In an effort to de novo discover novel TAK1 inhibitors, a DEL campaign was initiated. The target, TAK1-TAB1 fusion protein, was subjected to a DEL screen of 21 distinct DNA-encoded chemical libraries as a library pool. Parallel screening conditions were pursued, including various target concentrations and in the presence of 5Z-7-oxozeaenol. The DEL screen resulted in a wealth of enriched binders, and data analysis and profiling revealed actionable putative binders to follow up. One of the compounds prioritized for synthesis without the encoding tags was 3 (Figure 2a), which was derived from a library of 3.76 million compounds with two diversity cycles of chemistry.50

Figure 2.

(a) Structure of TAK1 DEL hit 3 and its analogues. aBiochemical Lanthascreen assay with TAK1-TAB1 fusion protein in the presence of 10 μM ATP.50 (b) Overlay of all TAK1 crystal structures available in the Protein Data Bank at the time this Perspective was written (22 structures in total). Crystal structures of DEL hits (PDB entries 7NTH and 7NTI(50)) are colored green. All other TAK1 crystal structures are depicted as white ribbons, with the structure of a previously reported type I TAK1 inhibitor (PDB ID 4L53(51) shown in white as a representative non-DEL-derived inhibitor (all other inhibitors present in the overlaid structures have been omitted for clarity). Hydrogen bonds from the DEL-derived inhibitors to the hinge region (residue Ala107) are shown as black dashes.

Compound 3 showed a biochemical IC50 value of 1.3 μM, was assumed to be a type I binder according to its DEL selection profile, and served as a starting point for subsequent structure–activity relationship (SAR) exploration. It was hypothesized that the amide carbonyl and the pyrrole NH interact with the hinge region of TAK1 while the pyrrolidine ring makes hydrophobic interactions in the back pocket. The DNA-linker region of the N-methyl amide was predicted to be most likely solvent exposed. Modification of the pyrrole core to an imidazole moiety gave rise to its close analogue, 4 (Figure 2a). Subsequently, the X-ray crystal structure of compound 4 bound to TAK1 was obtained which paved the way for SBDD of the series that resulted in compound 5 (Figure 2a) with an IC50 of 2 nM (at the assay detection limit) in a TAK1 biochemical assay.

Both 4 and 5 were seen to bind to the hinge of TAK1 in a type I fashion, interacting with the backbone of Ala107 via their imidazole NH and the amide carbonyl as a donor–acceptor pair (Figure 2b, colored green). Interestingly, an overlay of these structures with all TAK1 crystal structures available at the time this Perspective was written (22 structures in total) revealed that both compounds 4 and 5 induce a unique conformation of the hinge region in which Ala107 is flipped relative to previous TAK1 structures. This flipped conformation serves to displace the hinge backbone from its position observed in other structures (Figure 2b, white vs green cartoons), and the authors speculate that this difference could be contributing to the high selectivity of 4 and 5 for TAK1 over other kinases.

In conclusion, the series of type I TAK1 inhibitors discovered in the DEL screen revealed a unique binding mode in the hinge region that potentially contributes to the excellent kinome selectivity of these DEL-derived compounds when compared to the other known TAK1 inhibitors.

PAD4

PAD4 (peptidyl arginine deiminase 4) is a member of a set of five closely related proteins (PAD1–4 and PAD6) that carry out post translational modifications of peptidyl arginine residues via calcium dependent deimination of the positively charged residues to give neutral citrulline residues.52,53 While the family of proteins are widely distributed throughout the body and are involved in many important physiological and pathological processes, PAD4 is most highly expressed in in bone marrow, lymphoid tissues, and blood and plays a key role in NETosis.54,55

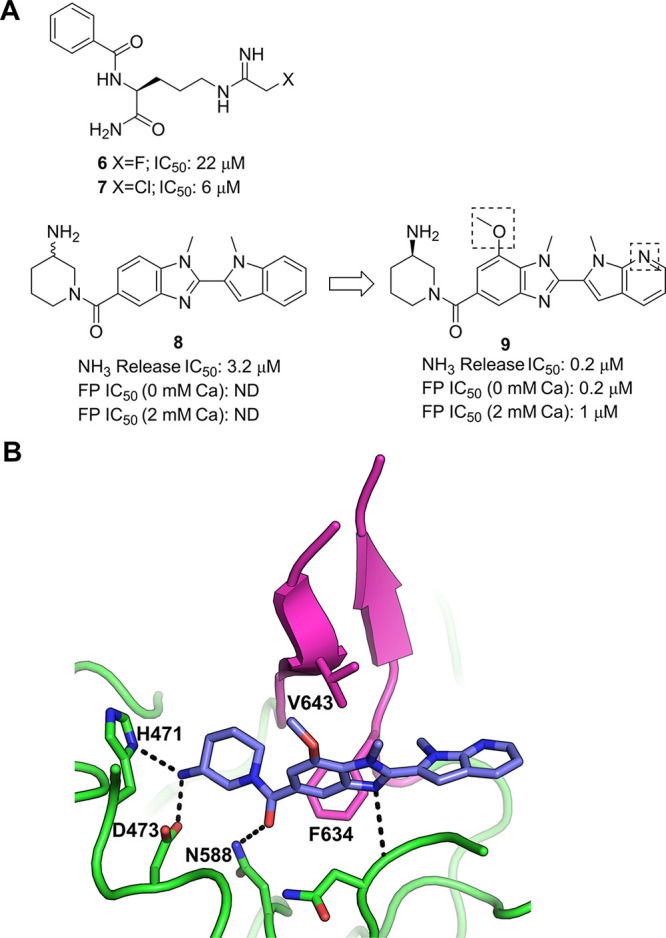

Early work on substrate analogues identified halo amidines 6 and 7 as irreversible inhibitors of PAD4 (Figure 3a), with modest activity and poor selectivity against other peptidyl arginine deiminases.56,57 However, in 2015, GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) reported a novel structural class of selective PAD4 inhibitors that were active against the calcium deficient protein.58 Screening of the GSK DNA-encoded library collection against PAD4 in the presence and absence of calcium led to the discovery of 8 (IC50: 3.2 μM, Figure 3a).

Figure 3.

(a) Chemical structures of PAD4 inhibitors including DEL-derived compounds 8 and 9.58 (b) Crystal structure of PAD4 bound by 9 (PDB entry 4×8G). Key polar interactions between the inhibitor and the protein are shown as black dashes. Residues 633–645 are colored magenta. This region, which contributes to the binding of 9 to PAD4, is disordered in the apo crystal structure (not shown).59

Substitution on the benzimidazole ring system and the introduction of an azaindole core led to an analogue with improved activity (9, IC50: 0.2 μM, Figure 3a). Analysis of the crystal structure of 9 with human PAD4 highlighted a number of key interactions that explained the observed SAR and helped refine the molecule further (Figure 3b). Furthermore, the X-ray structure revealed that the binding of the small molecule had induced a previously unseen conformation of a region of the protein. In the absence of calcium, residues 633–645 are disordered; however, 9 was seen to stabilize this region of the protein, with these residues forming a β-hairpin conformation (colored magenta in Figure 3b) that allows two lipophilic residues (Phe634 and Val643) to interact with the ligand. This was suggested to be the origin of the selectivity of these compounds over other members of the PAD family, as Phe634 is not present in PAD1–3 and PAD6.

Novel Protein–Ligand Interactions

BTK

Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) is a cytoplasmic nonreceptor kinase that plays a key role in the B-cell receptor (BCR) signaling pathway, and thereby plays a major role in the differentiation of B-cells, as well as other hematopoietic cells.60 Upregulation of BTK is now well-known to contribute to the development of multiple hematological cancers, including chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL) and mast cell lymphoma (MCL), among others.61 BTK has consequently received considerable attention as a cancer drug target, with five small molecule inhibitors approved to date for the treatment of various blood cancers.60,61 Despite these approved drugs proving hugely successful, there remains a desire to discover further BTK inhibitors with improved safety profiles, both as cancer therapeutics as well as treatments for diseases outside of the oncology setting, such as autoimmune and inflammatory diseases.62,63

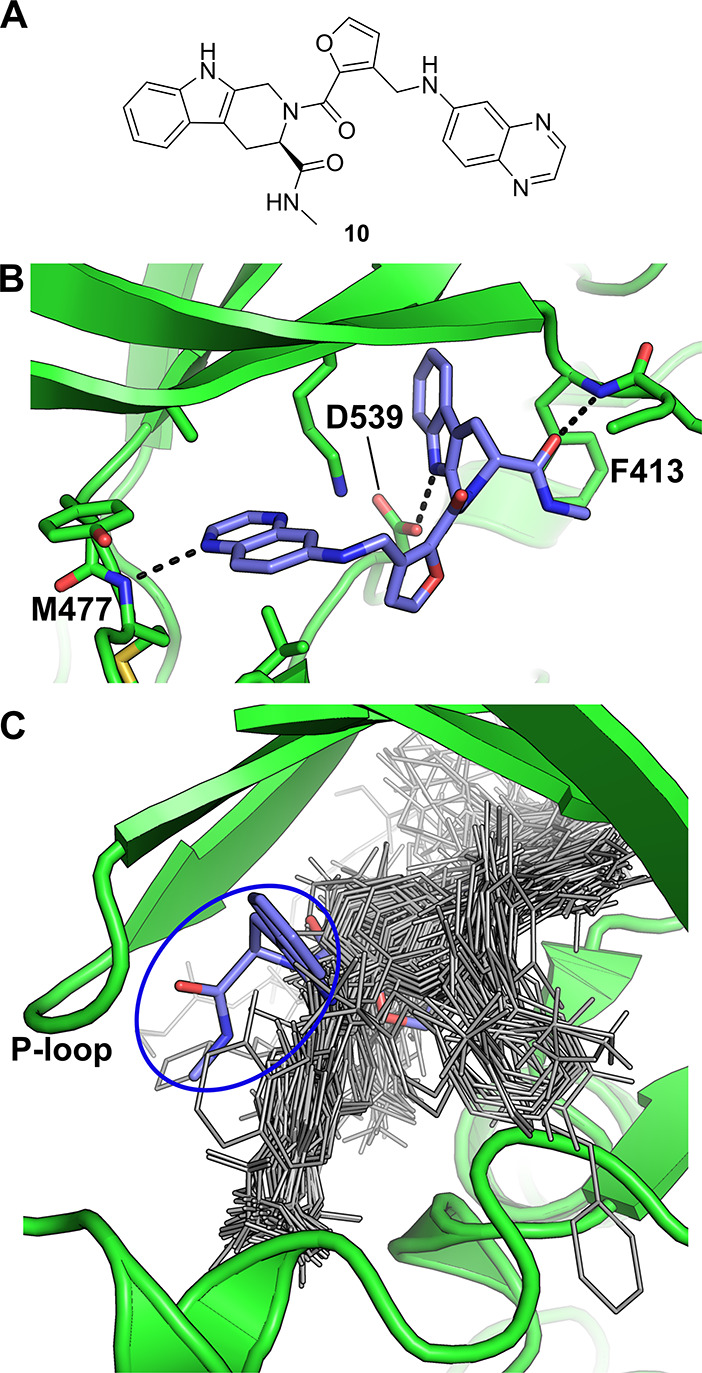

Toward this end, Cuozzo and co-workers screened a DNA-encoded chemical library composed of over 110 million compounds against BTK using multiple parallel selection conditions.64 This resulted in the identification of compound 10 which was synthesized off-DNA for further characterization (Figure 4a). 10 displayed an impressive (particularly for an unoptimized primary hit) IC50 of 0.55 nM in a probe displacement assay, and further showed promising activity (low nM IC50) and safety margins when tested in cellular assays using relevant cell lines. A cocrystal structure of BTK in complex with 10 was then determined, showing the inhibitor to bind to the ATP binding site of the kinase, forming hydrogen bonds to the backbone NH of M477 of the hinge region, as well as to the side chain of D539 and to the backbone NH of F413 of the P-loop (Figure 4b). Of particular note was that the tetrahydro-β-carboline moiety was seen to occupy a subpocket formed by a rearrangement of the P-loop which, at the time of publication, no known inhibitors had been seen to occupy (Figure 4c, blue oval). Cuozzo and co-workers then hypothesized that this previously unobserved binding mode may be the basis for the high binding affinity of 10 for BTK. Overall, this work represents an excellent example of a DEL screen yielding novel, highly active small molecule inhibitors of a validated and important drug target with a distinguished binding mode.

Figure 4.

DEL screen against BTK. (a) BTK inhibitor 10 discovered by Cuozzo et al.64 (b) Crystal structure of 10 bound to BTK (PDB entry 5U9D). (c) Structural alignment of all BTK-ligand complexes publicly available at the time 10 was reported, with 10 shown as blue sticks and all other compounds shown as gray lines. The tetrahydro-β-carboline moiety of 10 is circled in blue.

RIP1 Kinase

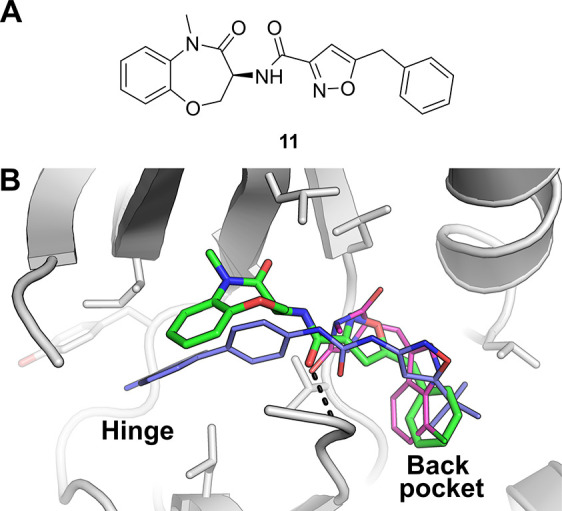

Receptor-interacting protein 1 kinase (RIP1 kinase or RIPK1) has emerged relatively recently as an important regulator of inflammation, apoptosis and necroptosis.65,66 Due to its role in these processes, RIPK1 is currently considered to be a promising drug target for the treatment of a range of acute and chronic inflammatory diseases.65,66 The first small molecule inhibitors of RIPK1 were the so-called “necrostatins”,67 with crystal structures of these compounds in complex with RIPK1 reported in 2013.68 These crystal structures showed that the necrostatins (and analogues) bind to a lipophilic pocket deep within the active site of the kinase. These compounds, however, showed relatively weak activity against RIPK1 (with IC50 values in the sub-μM/high nM range), which motivated researchers at GSK to biochemically screen a set of kinase-focused small molecules against RIPK1 in an attempt to discover inhibitors of this enzyme with improved properties.69 This led to the disclosure of a series of type II kinase inhibitors that, despite displaying considerably improved activity (compared to the necrostatins), were deemed suboptimal as lead compounds for further optimization (primarily due to the relatively high molecular weight of these compounds). In a further attempt to discover RIPK1 inhibitors with the potential for optimization toward possible clinical use, researchers at GSK then screened a DNA-encoded chemical library deck containing around 7.7 billion compounds against RIPK1.70 Following analysis of the screen output, a series of benzoxazepinones were identified as promising hits. Off-DNA synthesis and assessment of hit compound 11 (Figure 5a) in an FP-based assay provided a favorable IC50 of 10 nM, with assessment of the ability of 11 to inhibit the enzymatic activity of RIPK1 yielding an impressive IC50 (particularly for a primary hit) of 1.6 nM.

Figure 5.

(a) Chemical structure of 11, discovered by screening a DNA-encoded chemical library deck against RIPK1.70 (b) Comparison of the binding modes of various RIPK1 inhibitors. RIPK1 bound by 11 (PDB entry 5HX6, green carbons), overlaid with a type II RIPK1 inhibitor (PDB entry 4NEU, blue carbons) reported by Harris et al.,69 and with a necrostatin analogue (PDB entry 4ITH, magenta carbons) reported by Xie at al.68 The black dashes indicate a hydrogen bond from 11 to the backbone NH of residue D156.

A crystal structure of 11 in complex with RIPK1 was then determined, revealing a binding mode noticeably distinct from that of previously disclosed RIPK1 inhibitors (Figure 5b). The phenyl group of 11 was seen to bind to the same lipophilic back pocket as similar groups of the necrostatins (and analogues), however, the benzoxazepinone moiety was seen to extend toward the hinge region of the kinase (the region to which the adenine ring of its natural substrate ATP would be expected to bind), though, unlike the previously disclosed type II compound,69 was not seen to form contacts with the hinge region. This binding mode therefore classifies 11 as an “ATP-competitive type III” inhibitor, which at the time of publication was unique for a RIPK1 inhibitor. Interestingly, the assessment of 11 for kinome selectivity against a panel of over 450 kinases revealed the compound to be exquisitely selective, if not completely selective, for RIPK1. In addition, its physicochemical and DMPK properties were also determined to be favorable, marking 11 as a promising candidate for further optimization toward a potential clinical candidate. Indeed a further optimized analogue of 11 was progressed into clinical trials,71 highlighting the ability of DEL screening to yield a clinical candidate for a key drug target for which previous alternative hit-finding attempts had been unsuccessful (i.e., unsuccessful in discovering inhibitors with suitable properties).69

RIP2 Kinase

Receptor-interacting protein 2 kinase (RIP2 kinase or RIPK2), an intracellular kinase, has been identified as a key signaling partner for the pattern recognition receptors NOD1 and NOD2 (nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-containing proteins 1 and 2).72 ATP-driven autophosphorylation of RIPK2 activates downstream signal transduction. RIPK2 inhibitors targeting the NOD/RIP2 pathways have been shown to inhibit downstream cytokine production; therefore, RIPK2 inhibition represents an attractive therapeutic strategy for the treatment of inflammatory diseases.

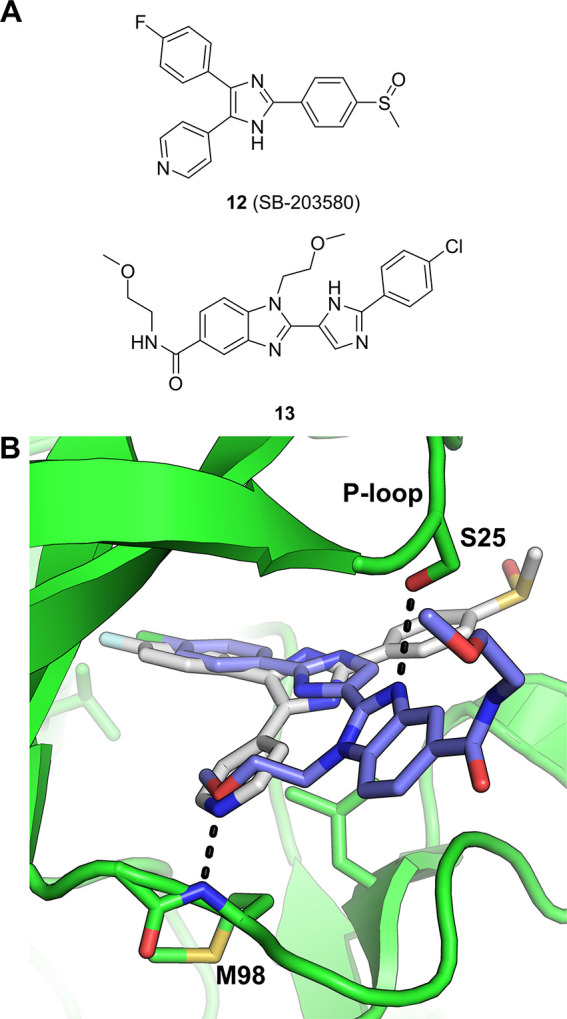

Several classes of RIPK2 inhibitors have been identified, including type I and II inhibitors, by screening known kinase inhibitor collections at GSK.73 Although these inhibitors, such as 12 (SB-203580, a p38 MAPK inhibitor, see Figure 6a),74 erlotinib and gefitinib75 (EGFR kinase inhibitors) effectively inhibit RIPK2 and block NOD2 driven cytokine production, these agents possess broad kinase activities, rendering them unsuitable as selective RIPK2 inhibitors for pharmaceutical use in treating inflammation.

Figure 6.

(a) Structures of RIPK2 inhibitors, 13 was discovered via DEL screening. (b) Overlaid structures of RIPK2-12 (SB-203580, PDB ID 5AR4) and RIPK2-13 (PDB ID 5AR5) complexes, highlighting the unique bidentate interaction of 13 in the ATP-binding site between the P-loop (S25) and hinge region (M98).76

Inhibitor 13, a novel benzimidazole chemotype (Figure 6a), was discovered by screening the GSK DEL collection against RIPK2.76 The X-ray structure of the RIPK2-13 complex revealed 13 to be a type I kinase inhibitor, albeit binding RIPK2 in an atypical manner (Figure 6b). 13 possesses an unusual methyl ether hinge-binding motif that accepts a hydrogen bond from the backbone NH of Met98, while the benzimidazole N3 forms a key hydrogen bond interaction with the side chain hydroxyl of Ser25 (located within the kinase P-loop). This binding mode of the methoxyethyl benzimidazole 13 was noted as being highly unusual for kinase inhibitors (likely due to the low prevalence of a serine at this position within P-loops across the kinome), and the investigators state that this unusual binding mode likely contributes to the superior kinase selectivity of 13 compared to other RIPK2 inhibitors, a notable achievement within the field.

Mer

Mer and Axl belong to the TAM family of receptor tyrosine kinases. They have both been implicated in the function of the immune response and the combination of Mer and Axl inhibition has gained interest as an attractive mechanism to enhance current immunotherapies.77 Mer is expressed by tumor-associated macrophages and activation of Mer promotes polarization from M1 to protumor M2-type macrophages which leads to apoptotic cell clearance through efferocytosis.78 Reversal of this macrophage polarization process through Mer inhibition should act to revive immune-mediated tumor suppression. While not an oncogenic driver in itself, Axl activity plays a complex role in immune regulation and can inhibit cytokine release, Toll-like receptor signaling, and T-cell activation by antigen-presenting dendritic cells. Inhibition of Axl in the tumor microenvironment is therefore also expected to be advantageous for enhancing the immune response.79

While small molecule TAM kinase inhibitors have progressed to the clinic,80−82 their varying degrees of selectivity across the TAM family and the broader kinome suggested there was still a clear requirement for highly selective dual Mer/Axl kinase inhibitors to evaluate for use in cancer immunotherapy. Thus, AstraZeneca embarked on a comprehensive lead-generation strategy encompassing virtual screening, FBLG, data mining, HTS and DEL screening.83

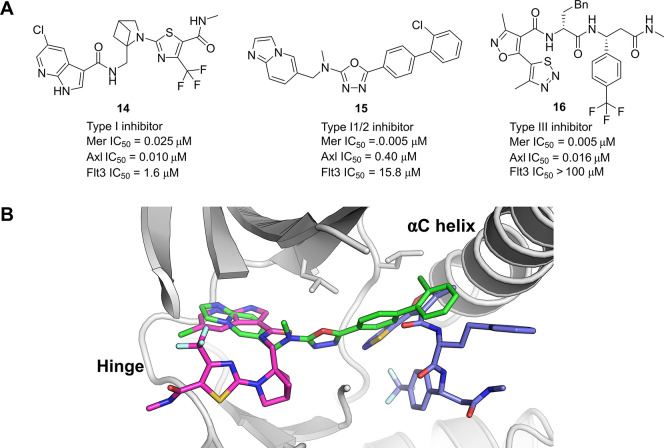

While the data mining and HTS were productive in terms of discovery of potent Mer kinase inhibitors, these efforts did not identify compounds with sufficient selectivity and developability profiles with which to progress further. A DEL screen, run in parallel alongside the other hit finding activities, utilized 20 selection conditions to be screened against a > 90-billion-member library collection. This approach was designed to probe multiple Mer constructs with and without ATP and to profile the output against several off-target proteins. This data set, in combination with a comprehensive downstream screening cascade, enabled an effective triaging process to focus down to hits which had a desired selectivity profile of dual Mer and Axl inhibition with >50-fold selectivity margin against the main antitarget Flt3 (14–16, Figure 7a). Upon solving the X-ray crystal structures of the hits bound to Mer, it was apparent how diverse the binding modes were among the different chemotypes (Figure 7b).

Figure 7.

(a) Chemical structures of the 3 Mer kinase inhibitors discovered via DEL screening. (b) Overlay of crystal structures of all three hits showing the different binding modes in complex with Mer, 14 (magenta carbons, PDB entry 7AW3), 15 (green carbons, PDB entry 7AW2), and 16 (blue carbons, PDB entry 7AW4).

While the azaindole series, exemplified by 14, showed a suitable activity profile across the TAM family kinases, it was found to be somewhat promiscuous when screened against the wider kinome which was not unexpected given the type I binding mode (Figure 7b, magenta carbons). Compound 15, containing a 1,3,4-oxadiazole core, was found to adopt a binding mode characteristic of a type I1/2 kinase inhibitor (Figure 7b, green carbons). The imidazopyridine formed a hydrogen-bonding interaction with Met674 at the hinge region while the rest of the molecule extended out toward the αC helix while maintaining a DFG-in conformation. This was only the second inhibitor reported to adopt such a binding mode for Mer. Pflug et al. previously reported the structure of EX172 which also spans from the hinge-region in the ATP pocket through to the kinase back pocket.84 In both cases, the compounds pack close to the αC helix which adopts an out conformation. The novel hinge-binding motif coupled with the extended pose of compound 15 were factors enabling the imidazopyridine series to display both high potency for Mer with an excellent selectivity margin over Flt3 and the wider kinase panel.

The third chemotype identified from the DEL screen was exemplified by compound 16. This was derived from a 3-cycle library containing two sets of amino acid building blocks. A lack of competition with ATP was observed in the biochemical Mer assay, run at both Km and high (above Km) ATP concentrations. Analysis of the crystal structure confirmed that the compound binds to an allosteric pocket near the αC helix, promoting a αC helix-out conformation with no interactions to the hinge region in the ATP pocket (Figure 7b, blue carbons). This represented a novel binding mode for a Mer kinase inhibitor. The thiadiazole and isoxazole rings bind to similar regions in the binding pocket compared with the biphenyl moiety in compound 15, while the rest of the compound extends away. Compound 16 engages in polar contacts with the catalytic Lys619 and the conserved Glu637 on the αC helix. The trifluoromethylbenzene group occupies the pocket of the DFG-Phe with the activation loop sitting in a DFG-out conformation. In contrast to the type I inhibitors, this type III binding mode conferred dual potency for Mer and Axl along with excellent selectivity against a broad set of kinases.

In summary, the DEL screening campaign delivered a variety of structurally distinct hits with different binding modes spanning across the orthosteric binding site, covering the more common type I, the less documented type I1/285 and the unique type III Mer kinase inhibitors. Both the type I1/2 and III conferred much improved selectivity profiles over existing Mer kinase inhibitors, with the imidazopyridine series developed into an effective in vivo probe compound taken into an immuno-oncology efficacy model.86

ATX

Autotaxin (ATX), also known as ENPP2 (ectonucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase family member 2), converts lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC) into the bioactive phospholipid derivative lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) and choline.87 LPA acts as an extracellular signaling molecule and exerts its biological activities through activation of the LPA receptors.88 The ATX/LPA axis has drawn considerable interest from the pharmaceutical industry due to its involvement in various disease areas such as cancer,89 pain,90 fibrosis,91 and inflammation.92 Elevated levels of ATX have been observed in the lungs of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) patients,93 a condition with high mortality rate and no curative treatment. Additionally, ATX inhibitors show promise as an attractive therapeutic strategy for the suppression of tumor progression.94

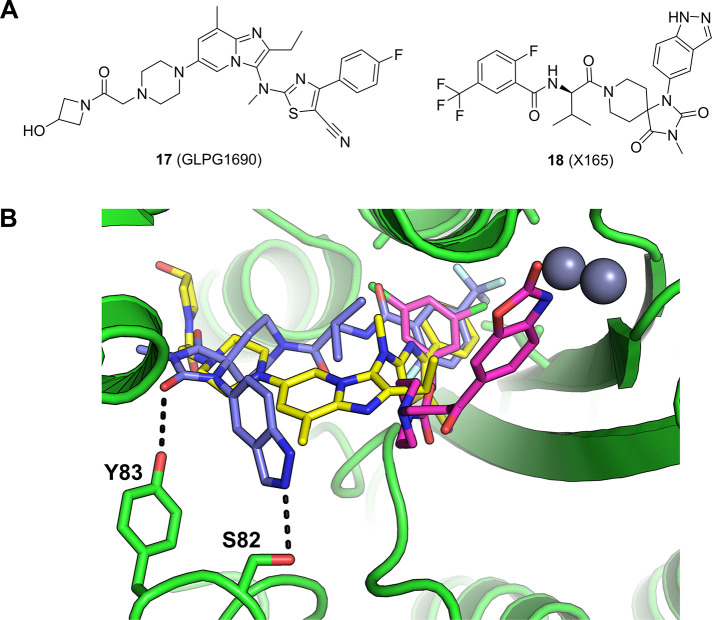

Several classes of ATX inhibitors have been reported by both academic research groups and industrial organizations. ATX inhibitors can be categorized as lipid-like structures that feature a linear lipophilic tail with acidic polar headgroup (e.g., PF8380, BI-2545), indole/indazole-derived ATX inhibitors, and other chemotypes95 including GLPG1690 (17),96 a Phase 3 clinical candidate which was recently terminated due to benefit-risk concerns.

A new class of ATX inhibitors was discovered in an affinity-mediated DEL screen of a 225 million member encoded chemical library. The selection campaign generated rich output, and several classes of structurally distinct, strongly enriched chemotypes emerged as putative binders. The synthesis of enriched exemplars without the encoding DNA tags resulted in highly potent ATX inhibitors.97 SAR exploration of the hit series was guided by the selection output, and further optimization resulted in the lead compound 18 (Figure 8a) with suitable ADME properties for testing in animal models.

Figure 8.

(a) Structures of autotaxin (ATX) inhibitors: 18 was discovered via a DEL screen reported by Cuozzo et al.97 (b) Crystal structure of 18 bound to ATX (blue carbons, PDB entry 6W35),97 overlaid with 17 (GLPG1690, yellow carbons, PDB entry 5MHP)96 and PF-8083 (magenta carbons, PDB entry 5L0K).96

The cocrystal structure of 18 with human ATX was obtained at a resolution of 1.98 Å (Figure 8b), which revealed a unique binding mode of this lead compound. Unlike previously reported structures such as PF-8380 or BI-2545, where the positions of the benzoxazolidinone98 and benzotriazole99 moieties superimpose perfectly and engage one of the catalytic zinc ions in the Zn binding pocket, 18 extends across the binding site to occupy both the hydrophobic pocket and the hydrophobic channel of autotaxin. Similar to GLPG1690,9618 does not engage the zinc ions in the Zn binding pocket. Interestingly, 18 takes trajectories that are different from the binding elements of GLPG1690 in the hydrophobic pocket and the hydrophobic channel (Figure 8b). The 2-fluoro-5-trifluoromethylphenyl substituent occupies the hydrophobic pocket while the hydantoin group carbonyl hydrogen bonds to the side chain of Tyr83. The indazole group is pointed to solvent and forms a hydrogen bond to Ser82 as well as forming an edge-to-face π–π interaction with Phe250 (not shown in Figure 8b for clarity).

As reported in the publication, the hit-to-lead campaign was accelerated by the SAR observation derived from rich DEL screen output, and the lead compound 18 (X165) was readily optimized into a candidate-quality compound.97

BRD4

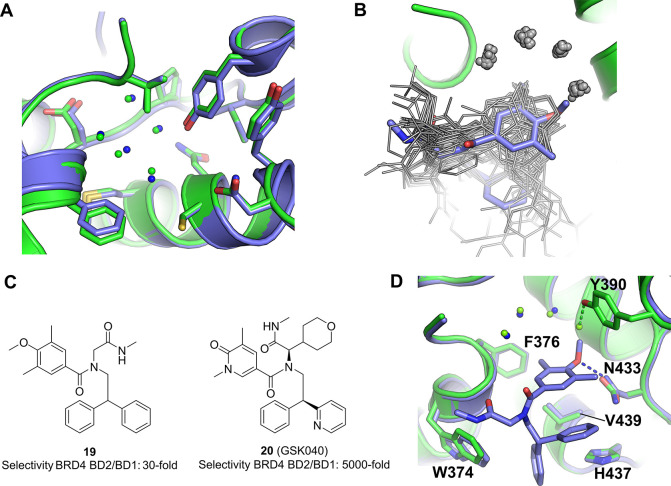

Bromodomain-containing protein 4 (BRD4) is a member of the bromo- and extra-c-terminal domain (BET) family of proteins. This family is composed of BRD2, BRD3, BRD4, and BRDT, all of which bind to acetylated lysine residues on histone tails and other proteins. Acetylated lysines function as epigenetic marks which, once bound to BET family proteins, result in the recruitment of RNA polymerase and other transcription-related proteins to these sites, thereby regulating both transcription initiation and elongation. BRD4 has attracted interest as an oncology target as it is often required for the expression of oncogenes, including Myc, in hematologic tumors and is translocated within NUT (nuclear protein in testis) genes in most NUT midline tumors. Bromodomains are the structural elements within these proteins that interact with acetylated lysines. BRD4 contains two bromodomains, bromodomains 1 and bromodomain 2. These two bromodomains are highly homologous and structurally very similar to each other (Figure 9a) and to bromodomains within other BET family members. Many early reports of BRD4 inhibitors did not explore the extent to which reported inhibitors bound to bromodomain 1, bromodomain 2, or both.

Figure 9.

(a) Overlay of BRD4 bromodomain 1 and bromodomain 2 showing the high degree of sequence and structural similarity between the two domains. BRD4 bromodomain 1 (PDB entry 2OSS) in blue and BRD4 bromodomain 2 (PDB entry 2OUO) in green. (b) Overlay of all 50 BRD4 bromodomain 2 complex structures publicly available at the time this Perspective was written, with the only compound discovered using affinity-mediated selection from a DNA-encoded chemical library shown in blue.109 The DNA-encoded chemical library hit uniquely displaces an otherwise conserved water molecule with its methoxy group. (c) BRD4 inhibitors discovered using DNA-encoded chemistry showing selectivity for bromodomain 2 over bromodomain 1. (d) BRD4 bromodomain 2 in complex with the DEL hit 19 (blue) overlaid with the apo protein (green).109

Over the past decade, there have been several reports in the scientific literature of BRD4 bromodomain 2 selective inhibitors, not least because pan-BET bomodomain inhibitors have been investigated in a range of clinical and preclinical studies and have shown nonideal therapeutic margins.100 Increasingly selective inhibitors have been reported101−109 with the most selective of these109 showing a selectivity ratio of about 5000-fold. The overlaid binding poses of 50 of these compounds can be seen in Figure 9b. There are a number of commonalities for most of these compounds including binding within the acetyl-lysine binding pocket and interactions with His437, Asn433, and Pro430, the retention of an arc of four highly conserved hydrogen-bound water molecules.

Currently there is one report of the use of DNA-encoded chemical libraries to discover BRD4 bromodomain 2 inhibitors.109 The screen within which the initial DEL hit was discovered was designed to enrich compounds that bound to BRD4 bromodomain 2 in the context of a construct that also contains bromodomain 1. Two additional constructs were screened in parallel, in which a key tyrosine in each bromodomain was mutated to an alanine to inactivate it. Bromodomain 2-selective compounds were seen to enrich against the wild-type construct and the construct with a mutation in bromodomain 1, but not against the construct with a mutation in bromodomain 2. One DEL hit (19) exhibiting this profile is shown in Figure 9c along with an optimized version of this hit, GSK040 (20) that was determined to have a 5000-selectivity for BRD4 bromodomain 2 over BRD4 bromodomain 1. This is the most selective compound reported to date. The DEL hit was crystallized with BRD4 bromodomain 2 and this structure is shown in Figure 9d, overlaid with the apo structure. The methoxyphenyl ring acts as the acetyl lysine mimetic, forming a hydrogen bond with Asn433. Additional interactions occur between His437 and Val439 with one of the phenyl rings. Perhaps most notably, the methoxy group extends toward and displaces one of the highly conserved water molecules observed in most structures of this bromodomain. This unique structural feature is shown in Figure 9b in which all 50 publicly available (at the time this Perspective was written) BRD4 bromodomain 2 complex structures have been structurally aligned (shown in gray), with the DEL hit 19 shown in blue. It is evident from this overlay that the methoxy group uniquely occupies the site that binds to one of the water molecules. Also discriminating this structure, no part of this DEL hit compound projects into the cleft between His437 and Asn433, which is the region within which most other selective compounds are believed to derive their selectivity.109 Further optimization of this compound at sites corresponding to both of the building blocks from which it was originally synthesized, and also at the linker attachment point, led the authors to discover GSK040 (20) which has a significantly increased affinity for BRD4 bromodomain 2 with an IC50 value of 5 nM, and a selectivity ratio of 5000-fold over BRD4 bromodomain 1.

InhA

Tuberculosis (TB) infects millions of people every year and contributed to the deaths of over 1.4 million in 2021.110 It was the leading cause of death from infectious diseases worldwide prior to the Covid-19 pandemic. The causative agent of TB, Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb), has been increasingly observed to possess resistance to the frontline therapies commonly used to treat TB, rifampicin and isoniazid.

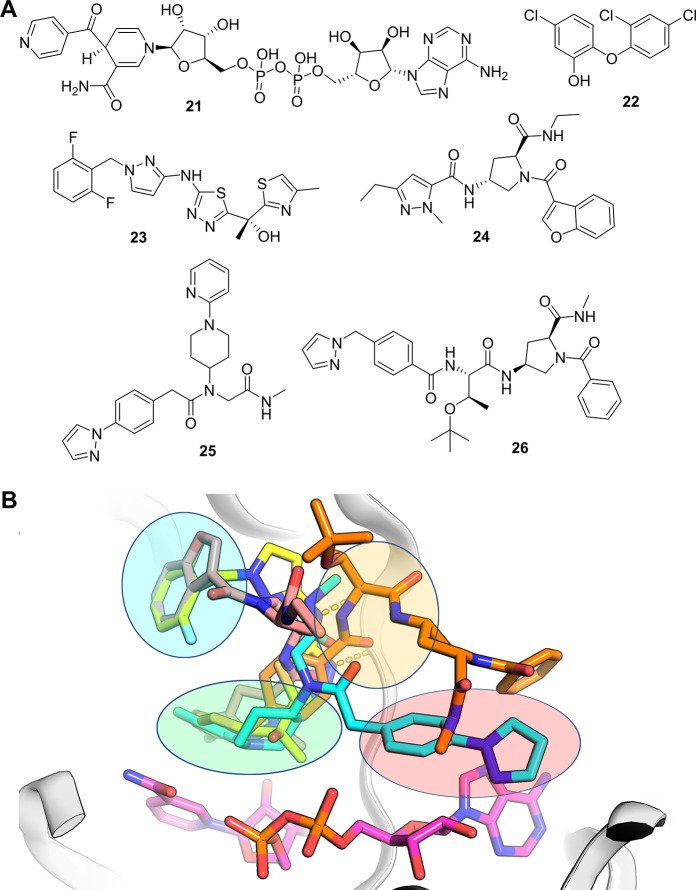

The enoyl-ACP reductase InhA, a primary target of isoniazid, catalyzes the NADH-dependent reduction of the acyl carrier protein (ACP) via an enoyl intermediate forming part of the fatty acid biosynthetic pathway essential for the formation of the waxy outer membrane mycolic acids of Mtb.111,112 Isoniazid, a prodrug that requires activation by KatG, forms a covalent adduct with the cofactor NADH (21). The isoniazid-NADH adduct acts as a picomolar inhibitor of InhA by competing with NADH.113−115 Many multidrug resistant TB strains exhibit resistance to isoniazid associated with mutations in at least five genes linked to isoniazid prodrug conversion, the majority of those mutations are linked to defects in the KatG gene and its upstream promoter.116−118 It was therefore thought that direct inhibitors of InhA would provide TB drugs for the isoniazid resistance strains without cross-resistance to isoniazid.

Several early attempts at identifying direct InhA inhibitors involved making analogs of triclosan (22),119 a common topical antibacterial agent which targets the essential role of ACP-enoyl-reductase (ER) in fatty acid synthesis. Triclosan, a transition-state mimetic, binds with a picomolar affinity to the NAD+-bound form of the enzyme. While successful attempts were made to make triclosan analogues with higher affinity to InhA by extending into the lipophilic region of InhA, the molecules retained the limiting physical properties of triclosan and were not progressed as a consequence.

In the early 2010s, researchers from GSK identified a methyl-thiazole series of InhA inhibitors (23,Figure 10a)120,121 with potent enzyme inhibition (InhA IC50 = 0.003 μM) translating into cellular potency (Mtb MIC = 0.19 μM). Like triclosan, this compound binds above the nicotinamide ring of NADH in the catalytic site and occupies the hydrophobic pocket as the triclosan analogues do (Figure 10b).122 A screen using a DEL containing 16.1 million compounds, published in 2014, identified an additional series of InhA inhibitors (24).123 While this series was shown to form different interactions with InhA than seen for previous inhibitors, it was shown to occupy a region of the binding site similar to compound 23 (Figure 10b).

Figure 10.

(a) Selected InhA inhibitors: 21 (isoniazid-NAD adduct), 22 (triclosan), 23 (methyl-thiazole series), 24 (InhA inhibitor from GSK DEL platform), 25 (pyridine-piperidine DEL series), and 26 (pyrrolidine DEL series). (b) Overlay of various InhA-inhibitor complex crystal structures. InhA shown as gray ribbons, NADH shown as sticks with magenta carbons. Distinct binding regions of the InhA binding site are indicated by colored ovals: green (catalytic site), blue (hydrophobic pocket), orange (hydrophilic site) and red (adenine-adjacent site). Compounds are depicted as sticks: 23 (PDB entry 4bqp, yellow carbons), 24 (PDB entry 4cod, salmon carbons), 25 (PDB entry 5g0v, cyan carbons), and 26 (PDB entry, 5g0w orange carbons). Hydrogen bonds between 23 and the backbone of Met98 are shown as yellow dashed lines.

Following this work, researchers from AstraZeneca and X-Chem ran a DEL screen of 66 billion encoded compounds using apo, NAD+-bound and NADH-bound forms of the enzyme,124 and identified multiple chemical series. Several of these series were shown by X-ray crystallography to bind to the previously identified catalytic, hydrophobic, and hydrophilic sites of InhA; however, two series, 25 and 26, (Figure 10a) were seen to extend into a region (adjacent to the ribose and adenine of the cofactor) to which no previous InhA inhibitors had been seen to occupy (Figure 10b, red circle).

Despite significant hopes for inhibitors of InhA, efficacious InhA inhibitors remain elusive. This may be due to hydrophobic properties of the inhibitors needed to mimic the long chain fatty acids required to make mycolic acid, the protective waxy layer of Mtb. It may also be that InhA is not as essential as once thought, and the isoniazid adduct inhibits additional targets within Mtb relating to its efficacy. Regardless of this, the two DEL studies showed how additional regions of InhA could be accessed and physical properties could be improved by making additional polar interactions with the target.

Novel Binding Sites

PAR2

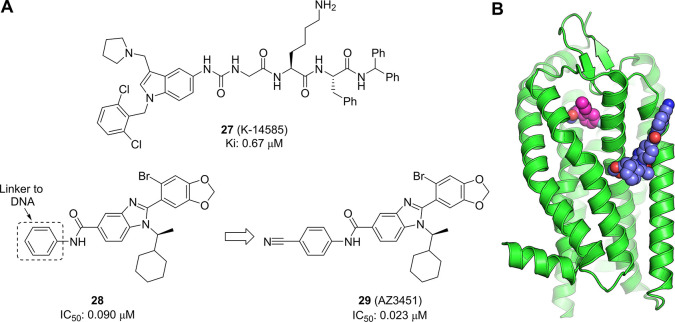

Protease-activated receptor-2 (PAR2) is a member of a family of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) that become irreversibly activated when proteolytic cleavage of their N-terminus reveals a tethered peptide ligand, which then binds and activates the transmembrane receptor domain. This family of GPCRs has been linked to a broad spectrum of diseases, including cancer and inflammation, making them the focus of significant pharmaceutical research efforts.125 A selective antagonist of PAR1 (vorapaxar) is marketed for the prevention of thrombosis, but the discovery of antagonists for the other PAR isoforms has proved to be more challenging. Early efforts to develop antagonists for PAR2 focused on modifications of known agonist peptides sequences. This work resulted in a number of peptides and peptidomimetics such as K-14585 (27, Figure 11a)126 with good affinity, but poor ADME properties. Nonpeptidic antagonists with improved properties were reported by several groups, but showed only moderate activity.127,128 However, a breakthrough came with the identification of a novel series of antagonists that were shown to bind to a previously unknown allosteric pocket in the transmembrane region. A group from AstraZeneca, Heptares and X-Chem were able to perform a successful DNA-encoded screen against this membrane-spanning protein by creating a thermostabilized form through multiple point mutations of the trans-membrane region.129

Figure 11.

(a) Chemical structure of peptidomimetic K-14585 (27) and the allosteric PAR2 antagonist AZ3451 (29) derived from an initial DEL hit 28. (b) Crystal structure of PAR2-29 complex (PDB entry 5NDZ). 29 is depicted as spheres with blue carbons, with the orthosteric binder AZ8838 shown in magenta, taken from PDB entry 5NDD.

The screen employed two variants of the protein, with one being exposed to the encoded library in solution before capture on the resin, while the other was precaptured onto resin prior to introduction of the library. An interesting set of structurally related benzimidazoles was identified in the analysis of the conditions using precaptured protein. Additional information regarding the binding interaction was obtained by the analysis of the DNA linker preference. The proposed hits were from a library that used both aryl and alkyl DNA linkers, and the data suggested a preference for an aryl linker. This was borne out when compound 28 (IC50 = 0.090 μM) showed good antagonist activity whereas the methyl amide was inactive (IC50 > 15 μM). Refinement of this hit through exploration of substitution on the phenyl ring led to improved allosteric antagonist AZ3451 (29, IC50 = 0.023 μM).

Interestingly, the profile of the benzimidazole family of compounds showed them to be competitive with known antagonists, but when a crystal structure was obtained of 29 in complex with PAR2 (Figure 11b) it was found that it occupied a novel binding pocket within the transmembrane region which did not overlap with the orthosteric site or other known allosteric pockets.130 The observed competition with known antagonists was proposed to derive from allosteric communication between binding sites within the GPCR. Together, this work provides another example of the ability of DEL screening to find novel, highly active hits for important drug targets with unprecedented binding modes.

WIP1

The wild-type p53-induced phosphatase (Wip1, encoded by PPM1D (protein phosphatase magnesium-dependent 1 δ)) is a serine/threonine phosphatase with oncogenic activity.131 Wip1 acts as a negative regulator of key proteins in the DNA damage response pathway, such as p53, p38 MAP kinase and ATM. Consistent with Wip1’s function as an oncogene, amplification and overexpression of PPM1D has been shown in multiple human cancer types, including breast and ovarian carcinomas.132,133 Gain-of-function Wip1 mutations have also been identified in primary human cancers.134 This supports the hypothesis that inhibition of Wip1 would be an attractive mechanism for suppression of tumor growth and evolution.135,136

While serine/threonine phosphatases are attractive therapeutic targets, they tend to have highly conserved catalytic domains, which makes development of selective, competitive inhibitors challenging.137 Early Wip1 inhibitors have been derived from natural substrate sequences of Wip1 by Yamaguchi et al.138 These cyclic phosphopeptides were designed to target the catalytic site through mimicking of the phosphorylated threonine in the pTXpY sequence of p38 MAP kinase. UNG2, was demonstrated to be a specific substrate for Wip1, and following further improvements to the molecule an activity for Wip1 with Ki of 110 nM was achieved.139 Some selectivity over PPM1A could be demonstrated, but this was balanced with a 30-fold reduction in the inhibitory effect for PPM1D. Due to the high negative charge of these inhibitors, cell permeability is poor, and thus their usage is restricted.

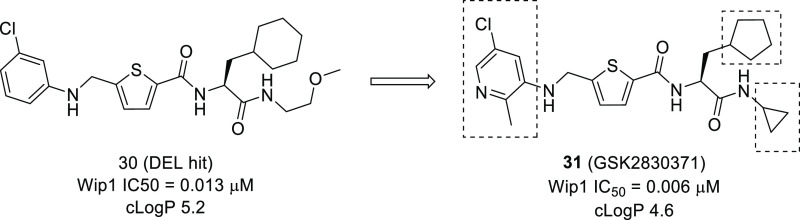

The combined synergies of parallel screening approaches were exemplified by GSK with report of a single series of small molecule Wip1 phosphatase inhibitors identified through both a biochemical and biophysical screen.140 A DNA-encoded library screen, carried out on full length Wip1, identified a potent inhibitor of Wip1 with an IC50 value of 13 nM (30, Figure 12). In parallel, a biochemical high-throughput screen, measuring the hydrolysis of an artificial substrate using truncated Wip1, was carried out and identified a compound with overlapping features to the DEL hit and an IC50 of 361 nM. These independently discovered hits were merged into a series containing an amino acid-like core region, which was designated the capped amino acids (CAA) series. Inhibition of Wip1 by 30 was found to be noncompetitive with respect to fluorescein diphosphate (FDP) and suggestive that the CAA compounds were binding outside of the catalytic active site. Pleasingly this allosteric profile appeared to translate into excellent selectivity over the two closely related PP2C family members, PPM1A and truncated PPM1K (phosphatase domain). No inhibition (IC50 > 30 μM) was also observed against a panel of 21 phosphatases. Cell permeability and pharmacokinetics of compound 30 could be suitably tuned with modest structural changes, resulting in the development of GSK2830371 (31), the first reported orally active, allosteric inhibitor of Wip1 phosphatase. This hit finding approach has demonstrated the ability of affinity screening to identify binders to novel allosteric sites, where selectivity at the orthosteric site was expected to be prohibitive for drug development, with the hit to lead optimization exemplifying the opportunity of DEL space to provide highly elaborated and potent hits in the first instance.

Figure 12.

Chemical structure of allosteric Wip1 inhibitor (30) and transformations used to yield GSK2830371 (31)

While there have been no reports of successful crystallization of the Wip1 protein, subsequent efforts were made to elucidate the mechanism of binding of GSK2830371 through other means.141 Comprehensive studies using computational modeling and functional mutagenesis were combined with the output from biochemical and biophysical assays. These results suggest that 31 binds through interactions with the hinge region, which is unique to PPM1D, causing movement in the flap region and locking it into a single, inactive conformation. While the mechanism by which 31 induces such conformational changes is unknown, one could postulate that it could be caused by binding of the ligand to multiple sites of the protein and acting as a “molecular glue”.

Novel Binding Mode of Induced Dimerization

ATAD2

ATAD2 (ATPase family, AAA domain-containing protein 2) also known as ANCCA (AAA nuclear coregulator cancer-associated protein) is an epigenetic reader, binding to acetylated lysines on histones and thereby affecting transcription. ATAD2 is overexpressed in many cancers due to coamplification with c-Myc,142 is a coactivator for transcription factors including ERα,143 E2F,144 and is a marker of poor prognosis in colorectal,145 breast and lung,146 endometrial147 and ovarian148 cancers. Genetic knockdown studies have shown that ATAD2 may be a viable oncology target.146 ATAD2 is composed of a left-handed four-helix bundle that, along with the ZA and BC loops, defines the acetylated lysine binding site within the bromodomain. The ATAD2 bromodomain interacts with acetylated lysines in appropriate sequence contexts and for example has been shown to pull down acetylated H3 and H4 peptides, an interaction that may be disrupted by mutations within the binding site149 and has also been utilized to develop a TR-FRET assay. ATAD2 has three distinct structural domains. An acidic N-terminal region provides tight but nonspecific binding to chromatin. The AAA ATPase domain drives nucleosome eviction. The bromodomain (BD) binds to acetylated lysines on histones, acting as an epigenetic reader.

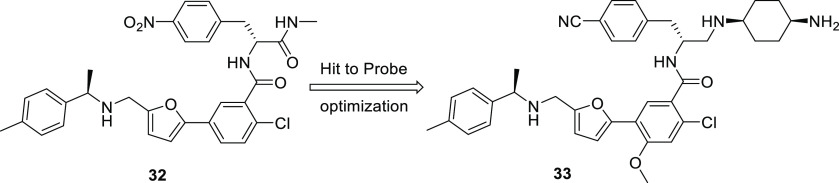

A range of ATAD2 inhibitors have been reported since 2014150−158 with IC50 values as low as single-digit nM. Discovery methodologies have been exclusively biophysical in nature; NMR, X-ray crystallography or affinity-mediated selection followed by TR-FRET with a probe derived from the tetra-acetylated histone H4 (BET), or TR-FRET directly. Consequently, compounds binding to any site that modulates peptide binding could have been discovered by any of these approaches. However, with the exception of the approach that utilized a DNA-encoded chemical library, all of the reported compounds occupy a set of overlapping sites within the bromodomain. Every X-ray crystallographic study conducted on these compounds showed them to interact with a largely consistent set of amino acids, mostly including asparagine 1064, or alternatively to reach deeper into the pocket and displacing bound water molecules. The one exception is the compound that was discovered using a DNA-encoded chemical library and affinity-mediated selection. This compound elicits its inhibitory effect using a completely distinct mechanism of action in that it induces ATAD2 bromodomain dimerization and prevents interactions with acetylated histones as a result, both in vitro, as well as with chromatin in cells. It is not clear why the approach that utilized a DNA-encoded chemical library provided compounds with such a distinct mode of action, but it may be related to the vastly larger number of compounds that were screened in this study.

Bayer and X-Chem collaborated to discover ATAD2 inhibitors using a deck of DNA-encoded chemical libraries and affinity-mediated selection.158 65 billion compounds in total were screened, with the hit derived from a 110-million-member sublibrary. The hit (32) IC50 was single-digit μM while follow-up compounds, exemplified by 33 (BAY-850), showed values as low as 22 nM by homogeneous time-resolved FRET (Figure 13). Target engagement was confirmed by thermal shift assay (TSA), microscale thermophoresis (MST), AlphaScreen, and BROMOscanTM, and a FRAP assay demonstrated displacement of full-length ATAD2 from chromatin in MCF7 cells. The BROMOscan assay indicated a high degree of selectivity over other bromodomain-containing proteins, and size-exclusion chromoatography indicated that the compound was able to induce dimerization of monomeric ATAD2. This artificially dimerized form of ATAD2 prevents interactions with acetylated histones in vitro, as well as with chromatin in cells. The hit compound enriched against a GST-tagged ATAD2 bromodomain construct in the affinity-mediated screen, and the GST-mediated dimerization of the target in this context may have also played a role in allowing for the discovery of compounds that can induce dimerization of monomeric ATAD2 themselves.

Figure 13.

BAY-850 (33), an isoform selective ATAD2 chemical probe, was optimized from an initial hit (32) discovered viaDEL screening.158

Discussion and Conclusions

The examples described above demonstrate the rich diversity of DEL screen outputs, both in terms of molecular structure and also in terms of binding modes, selectivity, and protein conformation. It is difficult to classify each of the examples mentioned above into discrete categories. We can, however, observe broad trends that speak to the novelty of the molecular interactions uncovered by DEL screening.

One such trend is proteins adopting conformations that have not been previously observed, as was seen in the c-MET and TAK1 examples. In the former case, a typically continuous helix is “broken” into two smaller orthogonal helices. In the latter, a peptide bond is flipped to change the hydrogen-bonding orientation of the backbone. In both examples, the compounds displayed unusually high selectivity across the kinome. We believe that this selectivity is likely to be the result of protein structural rearrangements. Similarly, in the PAD4 case, the DEL hit caused the organization of a disordered region into a previously unobserved β-hairpin. This reorganization and the hydrophic interactions with the inhibitor it enabled were justifiably thought to be responsible for the high selectivity the DEL compound displayed with respect to other PAD enzymes.

Another trend observed is DEL ligands interacting with proteins through novel interactions. In the BTK example, the compound engages a hydrophobic subpocket (through the tryptoline moiety) that was not observed in previous ligand complexes. In the RIPK2 cocrystal structure, it is revealed that the DEL-derived compound engages with the hinge hydrogen bond donor using a noncanonical acceptor (a methyl ether) and also makes another hydrogen bond interaction with a serine side chain. Again, high specificity is observed for RIPK2, likely due to the unique arrangement of those two H-bond interactions.

The ability to uncover multiple ligands with different binding modes in the same selection experiment is a hallmark of DEL screening. There is perhaps no better example of this than the Mer/Axl case study described here. In a single experiment, three completely distinct kinase inhibitory binding modes were uncovered: type I, type “I1/2”, and type III. Unsurprisingly, the type I inhibitor showed only modest selectivity, while the other two were very selective. Again, we see in this case that unusual binding modes seem to go hand-in-hand with high selectivity. This theme is reinforced by the RIPK1 case in which the compound was, once again, exquisitely selective. Here, an unprecedented (for RIPK1) “ATP-competitive type III” binding mode is observed.

Novel interactions are not confined to kinases. In the BRD4 case, a water molecule is displaced that is conserved among many if not all other known BRD4-inhibitor complexes. Additionally, this example is notable for what the compound does not do. It does not interact with a cleft between H437 and N433 that is occupied by most other BRD4 inhibitors.

Beyond finding new ways to interact with known binding pockets, sometimes DEL screening reveals the occurrence of completely unknown pockets. One such example is GPCR PAR2. Crystallographic studies revealed that the DEL-derived antagonist binds to a hitherto unknown pocket within the transmembrane region. Interestingly, the same DEL screen also produced agonists that bind to a well-characterized pocket in PAR2.

In the case of WIP1, while the ligand-protein complex could not be crystallized, a variety of biophysical experiments indicated the compound to be an allosteric binder that stabilized an inactive protein conformation. It achieved this by binding to a domain that is unique to Wip1 among other related phosphatases (conferring exquisite selectivity) and potentially by interacting with several domains at once, acting as an intramolecular “glue”.

A completely different inhibitory mechanism was observed in the ATAD2 case (although this had not been shown by X-ray crystallography). Here, induced dimerization led to inhibition. To the best of our knowledge, this mechanism of action is unprecedented among bromodomains. Unsurprisingly, this unique mechanism led to high selectivity, as indicated by BROMOScan data.

The lesson we take from these data is that in the search for ligands to proteins, there are many ways to skin the proverbial cat. If we have only seen a relatively narrow range of interactions for a given target, it is likely because we have only sampled a relatively narrow scope of chemistry. Again, this is not surprising since HTS decks only scratch the surface of the accessible chemical space and are likely populated with structural motifs shown to have bioactivity in the past. When truly large and unbiased libraries are interrogated, surprises happen. As shown above, these surprises, whether novel conformations, interactions, or binding sites, often lead in turn to a differentiated pharmacology.

High selectivity seems to be associated with these novel modes, as almost every case discussed above pointed to the high selectivity of the compounds. While detailed protocols for the selection experiments were lacking in most of the cited references, it is notable that counterselection with off-targets was not cited in all cases. Only the Mer/Axl report discussed its counterscreening strategy in detail, although competitive and/or mutant selections were cited for TAK, BTK, c-MET, BRD4, PAR2, and InhA. Therefore, we can hypothesize whether the high selectivity observed across these projects is the result of deliberate bias in the screening experiment, or rather a natural consequence of mining such large portions of chemical space. In either case, we can observe that the unusual binding interactions described here are not simply scientific curiosities, interesting from an academic perspective but with no real-world impact. Rather, novel interactions seem to lead directly to high selectivity, which can improve the odds of successfully arriving at a clinical candidate.

In conclusion, we feel that these observations bode well for the future of small molecule screening. As more building blocks become available and more DELs are synthesized, we will continue to expand the accessible chemical space. This expansion will further increase the already high probability that selection experiments will lead to unprecedented binding interactions and a new pharmacology. While this Perspective focuses mostly on previously validated targets, we can extrapolate these observations to novel targets as well. Beyond hit generation, potent and selective ligands like the kind described herein will serve as valuable probes, allowing researchers to validate novel disease targets in a pharmacologically relevant way. Having multiple probe compounds that address multiple sites in a novel protein would be a very powerful approach to rapidly derisking an unvalidated target. As the industry tackles newer and more difficult targets, unbiased exploration of the chemical space will be a valuable tool.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Ulf Börjesson and Dr. Benjamin C. Whitehurst for valued input and expertise.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- ACP

acyl carrier protein

- ADME

absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion

- ANCCA

AAA nuclear coregulator cancer-associated protein

- ATAD2

ATPase family, AAA domain-containing protein 2

- ATX

autotaxin

- BET

bromo and extra c-terminal domain

- BRD2–4

bromodomain-containing protein 2–4

- BTK

Bruton’s tyrosine kinase

- CAA

capped amino acid

- CAS

chemical abstracts service

- CLL

chronic lymphocytic leukemia

- c-MET

mesenchymal (to) epithelial transition factor (kinase)

- DEL

DNA-encoded library

- DMPK

drug metabolism and pharmacokinetics

- EGFR

epidermal growth factor receptor

- ENPP2

ectonucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase family member 2

- FBLG

fragment-based lead generation

- FDP

fluorescein diphosphate

- GPCR

G-protein-coupled receptor

- GSK

GlaxoSmithKline

- HTS

high throughput screening

- InhA

enoyl acyl carrier protein reductase

- IPF

idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

- LPA

lysophosphatidic acid

- LPC

lysophosphatidylcholine

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MCL

mast cell lymphoma

- Mer

(kinase expressed in) monocytes and tissues of epithelial and reproductive origin

- MST

microscale thermophoresis

- Mtb

Mycobacterium tuberculosis

- NOD1/2

nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-containing protein 1/2

- NUT

nuclear protein in testis

- TAK1

TGF-β-activated kinase 1

- TAM

TYRO3/AXL/Mer

- TB

tuberculosis

- TSA

thermal shift assay

- PAD4

peptidyl arginine deiminase 4

- PAR1/2

protease-activated receptor 1/2

- PDB

protein data bank

- P-loop

phosphate-binding loop

- PPM1D

protein phosphatase magnesium-dependent 1 δ

- RIPK1

receptor-interacting protein 1 kinase

- RIPK2

receptor-interacting protein 2 kinase

- SAR

structure–activity relationship

- SLL

small lymphocytic lymphoma

- SBDD

structure-based drug design

- WIP1

wild-type p53-induced phosphatase 1

Biographies

Dr. Gavin W. Collie received his Ph.D. from the UCL School of Pharmacy in 2012. He then completed postdoctoral positions at the European Institute of Chemistry and Biology (France) and the Institute of Cancer Research (UK). He is currently an Associate Principal Scientist at AstraZeneca, focusing on structural biology and cancer drug discovery.

Dr. Matthew Clark, CEO, X-Chem is a world-recognized innovator and leader in the DNA-encoded library (DEL) field. He was part of X-Chem’s founding team and served as VP of chemistry and SVP of research prior to his appointment as CEO. Before joining X-Chem, Matt was director of chemistry at GlaxoSmithKline, where he led the group responsible for DEL design and synthesis. He began his professional career at Praecis Pharmaceuticals, where he played a key role in the early development of DEL. He received his B.S. in biochemistry from the University of California, San Diego, holds a Ph.D. in chemistry from Cornell University, and conducted postdoctoral studies at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Dr. Anthony Keefe, SVP of Innovation, X-Chem. Tony has over 25 years of experience with encoded libraries and affinity-mediated discovery and helped to establish the DEL platform at X-Chem. Previously he worked at Archemix, where he developed the first-ever fully modified aptamers, improving their therapeutic potential by making them resistant to biologically mediated degradation. Prior to that he was a postdoctoral fellow in the laboratory of Nobel Laureate Jack Szostak at Harvard Medical School/Massachusetts General Hospital, developing mRNA display technology. Tony’s achievements in the Szostak lab include discovery of the first novel functional protein discovered independently of biology and a new protein affinity tag. Tony received a B.Sc. in chemistry from Exeter University, U.K., and a Ph.D. in chemistry from the University of Birmingham, U.K.

Dr. Andrew Madin completed his Ph.D. in organic synthesis at Imperial College, London. Following postdoctoral studies at the University of California, Irvine, he went on to work as a medicinal chemist, primarily in the areas of neuroscience and oncology. Currently, he is a member of the DNA Encoded Library screening group within AstraZeneca.

Dr. Jon Read is a research scientist with over 20 years of experience in the Drug Discovery Industry. Jon is the Director of the protein structure team within AstraZeneca UK and leads the epigenetics strategy within Discovery Sciences at AstraZeneca. He has led numerous hit generation projects within oncology, neuroscience, and infection and is passionate about identifying and characterizing small molecule hits for drug targets to support their optimization into drugs.

Dr. Emma Rivers obtained her Ph.D. in organic chemistry from Imperial College London before joining GSK as a medicinal chemist working on both hit to lead and lead optimization programs within neuroscience. She joined AstraZeneca in 2015 working on the DNA-encoded library collaboration with X-Chem and is currently a Director of Medicinal Chemistry within the Hit Discovery Department, leading the DEL chemistry team responsible for the workup and hit follow up of DEL screens for projects from across the therapeutic areas including oncology, cardiovascular, respiratory, and neuroscience.

Dr. Ying Zhang obtained her Ph.D. in organic chemistry from The George Washington University and was an Intramural Research and Training Fellow in medicinal chemistry at NIDDK, NIH before joining ArQule and Merck Research Lab (formerly SPRI Schering Plough) as a discovery chemist participating in various Lead Discovery programs and ALIS platform. She joined X-Chem in 2010 and currently serves as VP of Discovery, where she helped to establish and continues to innovate X-Chem’s DEL platform serving the small molecule drug discovery industry.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Dragovich P. S.; Haap W.; Mulvihill M. M.; Plancer J.-M.; Stepan A. F. Small-Molecule Lead-Finding Trends across the Roche and Genentech Research Organizations. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 65 (4), 3606–3615. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c02106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wildey M. J.; Haunso A.; Tudor M.; Webb M.; Connick J. H.. High-Throughput Screening. In Annu. Rep. Med. Chem.; Academic Press, 2017; pp 149–195. [Google Scholar]

- Weigelt D.; Dornage I.. Lead Generation Based on Compound Collection Screening. In Lead Generation: Methods and Strategies; Wiley-VCH, 2016; pp 93–132. [Google Scholar]

- Harris J. C.; Hill R. D.; Sheppard D. W.; Slater M. J.; Stouten P. F. W. The Design and Application of Target-Focused Compound Libraries. Comb. Chem. & High Throughput Screening 2011, 14, 521–531. 10.2174/138620711795767802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posy S. L.; Hermsmeier M. A.; Vaccaro W.; Ott K.-H.; Tofferud G.; Lippy J. S.; Trainor G. L.; Loughney D. A.; Johnson S. R. Trends in Kinase Selectivity: Insights for Target Class-Focused Library Screening. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 54–66. 10.1021/jm101195a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark A. M.; Acharya R. A.; Arico-Muendel C. C.; Belyanskaya S. L.; Benjamin D. R.; Carlson N. R.; Centrella P. A.; Chiu C. H.; Creaser S. P.; Cuozzo J. W.; et al. Design, Synthesis and Selection of DNA-Encoded Small-Molecule Libraries. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2009, 5, 647–654. 10.1038/nchembio.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodnow R. A.; Dumelin C. E.; Keefe A. D. DNA-encoded chemistry: enabling the deeper sampling of chemical space. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2017, 16 (2), 131–147. 10.1038/nrd.2016.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown D. An Analysis of Successful Hit-to-Clinical Candidate Pairs. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 66, 7101–7139. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.3c00521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reymond J.-L.; van Deursen R.; Blum L. C.; Ruddigkeit L. Chemical space as a source for new drugs. Med. Chem. Commun. 2010, 1, 30–38. 10.1039/c0md00020e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Drew K. L. M.; Baiman H.; Khwaounjoo P.; Yu B.; Reynisson J. Size estimation of chemical space: how big is it?. J. Pharmacy and Pharmacol. 2012, 64, 490–495. 10.1111/j.2042-7158.2011.01424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetzel S.; Bon R. S.; Kumar K.; Waldmann H. Biology-Oriented Synthesis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 2011, 50, 10800–10826. 10.1002/anie.201007004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper G.; Pickett S. D.; Green D. V. S. Design of a Compound Screening Collection for use in High Throughput Screening. Comb. Chem. & High Throughput Screening 2004, 7, 63–70. 10.2174/138620704772884832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacoby E.; Schuffenhauer A.; Popov M.; Azzaoui K.; Havill B.; Schopfer U.; Engeloch C.; Stanek J.; Acklin P.; Rigollier P.; et al. Key Aspects of the Novartis Compound Collection Enhancement Project for the Compilation of a Comprehensive Chemogenomics Drug Discovery Screening Collection. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2005, 5, 397–411. 10.2174/1568026053828376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Follmann M.; Briem H.; Steinmayer A.; Hillisch A.; Schmitt M. H.; Haning H.; Meier H. An approach towards enhancement of a screening library: The Next Generation Library Initiative (NGLI) at Bayer — against all odds?. Drug Discovery Today 2019, 24 (3), 668–672. 10.1016/j.drudis.2018.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuffenhauer A.; Schneider N.; Hintermann S.; Auld D.; Blank J.; Cotesta S.; Engeloch C.; Fechner N.; Gaul C.; Giovannoni J.; et al. Evolution of Novartis’ Small Molecule Screening Deck Design. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 14425–14447. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c01332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Sanchez R.; Besley S.; Quayle J.; Green J.; Warren-Godkin N.; Areri I.; Zeliku Z. Maintaining a High-Quality Screening Collection: The GSK Experience. SLAS Discovery 2021, 26 (8), 1065–1070. 10.1177/24725552211017526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeSimone R. W.; Currie K. S.; Mitchell S. A.; Darrow J. W.; Pippin D. A. Privileged Structures: Applications in Drug Discovery. Comb. Chem. & High Throughput Screening 2004, 7, 473–493. 10.2174/1386207043328544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin Y. C.; Kofron J. L.; Traphagen L. M. Do Structurally Similar Molecules Have Similar Biological Activity?. J. Med. Chem. 2002, 45 (19), 4350–4358. 10.1021/jm020155c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baell J. B.; Holloway G. A. New Substructure Filters for Removal of Pan Assay Interference Compounds (PAINS) from Screening Libraries and for Their Exclusion in Bioassays. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53 (7), 2719–2740. 10.1021/jm901137j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.; Franzini R. M.. Design Considerations in Constructing and Screening DNA-Encoded Libraries. In DNA-Encoded Libraries: Topics in Medicinal Chemistry; Springer, 2022; pp 123–143. 10.1007/7355_2022_147. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tomberg A.; Bostrom J. Can easy chemistry produce complex, diverse, and novel molecules?. Drug. Discovery Today 2020, 25 (12), 2174–2181. 10.1016/j.drudis.2020.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.; Clark M. A. Design concepts for DNA-encoded library synthesis. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2021, 41, 116189 10.1016/j.bmc.2021.116189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Does Size Matter in DEL Screening?; X-Chem, 2023. https://www.x-chemrx.com/does-size-matter-in-del-screening/#:~:text=Our%20interpretation%20of%20this%20analysis,chemistry%20(and%20eventually%20candidates.

- Gherardi E.; Birchmeier W.; Birchmeier C.; Vande Woude G. Targeting MET in cancer: rationale and progress. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2012, 12 (2), 89–103. 10.1038/nrc3205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recondo G.; Che J.; Jänne P. A.; Awad M. M. Targeting MET Dysregulation in Cancer. Cancer Discovery 2020, 10 (7), 922–934. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-19-1446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]