Abstract

The psychedelic prodrug psilocybin has shown therapeutic benefits for the treatment of numerous psychiatric conditions. Despite positive clinical end points targeting depression and anxiety, concerns regarding the duration of the psychedelic experience produced by psilocybin, associated with enduring systemic exposure to the active metabolite psilocin, pose a barrier to its therapeutic application. Our objective was to create a novel prodrug of psilocin with similar therapeutic benefits but a reduced duration of psychedelic effects compared with psilocybin. Here, we report the synthesis and functional screening of 28 new chemical entities. Our strategy was to introduce a diversity of cleavable groups at the 4-hydroxy position of the core indole moiety to modulate metabolic processing. We identified several novel prodrugs of psilocin with altered pharmacokinetic profiles and reduced pharmacological exposure compared with psilocybin. These candidate prodrugs have the potential to maintain the long-term benefits of psilocybin therapy while attenuating the duration of psychedelic effects.

Introduction

Treatment-resistant depression and anxiety disorders remain significant unmet medical needs, affecting hundreds of millions of people worldwide (World Health Organization [WHO], 2023). Over the last 30 years, the current standard of care has been mostly limited to the administration of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), selective serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), and benzodiazepines. These conventional therapeutics maintain notable side effects and fail to achieve long-term benefits, resulting in dependency and resistance to treatment. These challenges warrant the continuous search for rapid-acting antidepressant and anxiolytic medicines. For thousands of years, psychedelic substances have been used in human cultures for holistic healing and spiritual purposes. In recent years, numerous drug development efforts have focused on the neuroactive, serotonergic functions of these natural hallucinogens for their therapeutic potential.1 Among these agents, there has been an increased interest in the use of psilocybin for the treatment of numerous psychiatric disorders.2 Found in various species of fungi, psilocybin is a naturally occurring prodrug of the psychedelic compound psilocin.3−6 Recent clinical trials have reported compelling results demonstrating psilocybin’s therapeutic efficacy in addressing treatment-resistant depression (TRD).7−10 Significant and meaningful improvements in depression scores were presented, with long-term benefits lasting weeks and, in some individuals, up to six months post-treatment. Similarly, clinical trials enrolling patients with moderate to severe major depressive disorder (MDD) and cancer-related distress (CRD) demonstrated substantial and durable antidepressant effects from psilocybin-assisted therapy, lasting up to 12 months.11−13 These rapid and persistent antidepressive and anxiolytic effects produced by psilocybin are characteristically accompanied by a potent psychedelic episode lasting up to 6 h from the time of dosing.4,7,14−16 The long duration of this altered state is attributed to the pharmacokinetic (PK) profile of psilocybin.6,17 Upon ingestion, exposure to acidic conditions within the GI tract, along with intestinal and hepatic alkaline phosphatase, leads to the dephosphorylation of psilocybin, producing elevated levels of systemic psilocin. Participants consuming 25 mg of psilocybin experience significant systemic psilocin exposure, with plasma levels peaking at 2 h and enduring for up to 24 h postadministration.6,17

Concerns around the duration of the psychedelic experience, which inevitably requires hours-long clinical supervision and potential psychotherapeutic integration, and also prolongs adverse toxic side effects, significantly limit the widespread therapeutic application of psilocybin. Additionally, subjective reports of acute drug effects induced by psilocybin suggest that broad experiences, ranging from acute mystical-based effects to challenging experiences of paranoia, grief, and fear, prove to produce an enduring sense of well-being and positive emotional benefits.18 To this end, it would stand to reason that psilocybin-based treatment maintains a wide therapeutic index with respect to the effective dose range. Indeed, no significant correlation was observed between subjective drug effects and body weight (broadly ranging from 49 to 113 kg). This supports the fixed-dose strategy used by current clinical trials.7,9−12,18

Owing to the somewhat dose-independent responses associated with the therapeutic effect of psilocybin, this study explores an alternative approach to reduce the extent and intensity of the psychedelic experience while maintaining the therapeutic benefit. We propose to modify the pharmacokinetics of systemic psilocin exposure. It can be argued that establishing a rapid onset and shorter duration of the acute psychoactive effects while still retaining the long-term benefits reported for psilocybin-assisted treatment will accommodate a more amendable psychotherapeutic process. To investigate this possibility, we engineered a library of novel prodrug derivatives (NPDs) of psilocin. These NPDs are modified versions of the natural prodrug psilocybin, with substitutions at the 4-hydroxyl group attached to the core indole ring.

These substitutions involve incorporating different established metabolically amenable linkers attached to diverse R groups. This library consists of twenty-eight unique compounds represented by nine distinct prodrug classes. To investigate this diversity, we screened all NPDs for in vitro metabolic stability using human intestine, liver, and serum extracts. Pharmacokinetic (PK) analysis measuring systemic plasma levels of generated psilocin and resultant neuroactivity against the 5-HT2A target receptor was also assessed in orally treated healthy mice. Outcomes of these screens revealed five unique prodrug derivatives that produced notable acute levels of plasma psilocin and reduced overall systemic exposure, as well as acute neuroactive responses approaching or exceeding levels induced by an equivalent dose of psilocybin. Of these active prodrugs, two distinct molecules produced long-term anxiolytic benefits in chronically stressed mice evaluated in the marble-burying psychiatric model.

Results

Chemical Synthesis

We embarked on the design and synthesis of unique prodrugs of psilocin, each harboring a unique cleavable moiety on the core indole ring. Psilocin bears a hydroxyl group at the 4-position of its indole core, resulting in a heterocyclic phenolic core. The hydroxyl group of phenol-based drugs has been extensively utilized as a handle for further derivatization, particularly to produce prodrugs.19 Taking advantage of the wide range of in vivo enzyme-cleavable bonds that can be processed to reveal a hydroxyl group, several types of linkers were considered in designing our pool of NPDs, including esters, carbonates, and phosphates, among others, which were all attached to the 4-hydroxy group of psilocin (Figure 1). Additionally, within each distinct group of prodrug linkers, various electronic properties and hydrophilicities were introduced to further modify the physical and chemical features of the final prodrugs, namely, their solubility and chemical stability.

Figure 1.

(A) Synthesis of psilocin (1) from 4-benzyloxy-indole (2). (B) General scheme for the synthesis of 4-OH-derived prodrugs. (C) General scheme for the synthesis of 4-OH-derived prodrugs with masked indole-NH to achieve orthogonal derivatization. See the Experimental Section for reagents, detailed synthetic procedures, and reaction yields. TIPS = triisopropylsilyl, Bn = benzyl.

To begin, psilocin was synthesized following the procedures found in the existing literature20 with slight modifications that allowed us to utilize O-benzyl-protected 4-hydroxy-indole as the building block (Figure 1A). Following the production of psilocin, different prodrug linkers were installed simply by reacting the corresponding activated linker precursors with the 4-hydroxy group of psilocin (Figure 1B). This strategy was successful in generating the majority of our designed prodrugs; however, in some cases, the indole-NH interfered with modifications on the 4-OH and orthogonal derivatization was not feasible. To circumvent this issue, a triisopropylsilyl (TIPS) protection step was introduced to the synthesis to mask the indole-NH that was revealed following the installation of the corresponding linker (Figure 1C).21 Subsequent to the 4-OH derivatization, in most cases, the N-TIPS protected moiety was also tested as an additional unique prodrug. Moreover, attempts to synthesize some of the designed prodrugs from psilocin led to the adventitious formation of NH-derivatized species, which were tested separately. Following these two general synthetic routes, a total of 28 psilocin prodrugs within 9 distinct structural groups were synthesized (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Chemical structures of the synthetic novel prodrug derivatives (NPDs) of psilocin. Where applicable, the corresponding X substituent is indicated under each unique R group.

In Vitro Prodrug Metabolism

Orally administered psilocybin is subject to significant first-pass metabolism, involving dephosphorylation at the 4-hydroxyl position, producing the bioactive form psilocin.6,4,17,22−27 This dephosphorylation occurs in various compartments within the body. Chemical hydrolysis of the phosphate group readily occurs within the acidic environment of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract.6,17,23,24,26 Enzymatic cleavage is mediated by alkaline phosphatase and nonspecific esterases when psilocybin is absorbed through the intestinal lining and upon passage through the liver.4,17,25−27 Ultimately, the generation of systemic levels of the more lipid-soluble psilocin enhances bioavailability throughout the body, specifically making it amenable for transport across the blood–brain barrier and stimulation of receptors in the brain to induce its neuroactive effects.16,28,29

Chemical modification of the cleavable moiety at the 4-hydroxyl position of these NPDs has the potential to modify the overall metabolic profile of these molecules. This altered metabolic potential will ultimately affect the kinetics of plasma psilocin levels and their overall bioavailability. Hence, by altering the rate at which systemic psilocin levels rise and changing the overall exposure of this neuroactive agent, we may be able to alter the extent and duration of the psychedelic effect. Various assays are available to evaluate the potential metabolism of candidate drugs in vitro.(30,31) A commonly established approach is the use of subcellular fractions derived from relevant organs involved in drug metabolism. Human microsomes, isolated from liver and intestinal tissues, contain a wide array of relevant enzymes involved in biotransformation and drug metabolism.32−34 S9 from either liver or intestinal tissues contain both microsomal and cytosolic components. Except for membrane-associated factors, S9 fractions essentially encompass the same metabolic enzyme profile as intact cells.35,36 To determine the in vitro metabolic parameters that might predict the PK and drug reactivity profile of each prodrug, all molecules, prepared at an assay concentration of 2.5 μM, were incubated independently in human serum and in S9 or microsomal cell-free fractions derived from both human liver and intestinal donor organ. Each molecule was also assessed for aqueous stability independent of enzyme activity in the assay buffer alone. Biotransformation of the parent prodrug into the psychoactive metabolite psilocin was monitored for each molecule in 20-min intervals for a duration of 2 h by liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC-MS) (Figures S1 and S2). As a relevant comparator, the natural prodrug psilocybin (PCB) was also assessed for its in vitro metabolic stability. Table 1 presents the in vitro half-life (T1/2) for each novel prodrug evaluated independently in each biological fraction. Table 2 lists the emergent concentration of psilocin (in μM) at the end point of each assay. Psilocybin, which is phosphorylated on the 4-hydroxyl of the indole core, proved to be considerably resilient to metabolism under these in vitro conditions, with only a marginal reactivity seen in intestinal-based fractions (Tables 1 and 2, Figure S3). In contrast, many NPDs designed to be specifically targeted by esterase-directed cleavage were readily metabolized to psilocin in all biological fractions tested. Of these, the ester-based prodrug derivatives ES01 and ES02 produced notable enzyme-mediated cleavage profiles (Figures S4 and S5, respectively), with significant metabolism detected in liver- and serum-based fractions and appreciable activity seen in intestinal isolates. Notable metabolic conversion was also seen in one carbonate-based prodrug, C03 (Figure S6), and one thiocarbonate derivative, T01 (Figure S7). The chemical diversity in the R groups within this collection of compounds does not suggest that any structural feature is fundamentally integral in promoting greater cleavage of the prodrug moiety to release psilocin; however, aromatic (e.g., R = benzyl, methoxybenzyl, halogenated benzyls) and aliphatic (e.g., R = ethyl, cyclopropyl) side chains are increasingly represented in metabolically labile compounds. Additionally, the removal of a zwitterionic state may make these compounds better esterase substrates. A compelling outcome in the above analysis is the notable metabolic activity detected in human serum samples against many of the NPDs (Tables 1 and 2, Figures S4, S5, S6, and S7). This is in stark contrast to that of psilocybin, which is considerably stable in this biological fraction (Figure S3). These NPDs, proving amenable to serum-based metabolism, present an interesting therapeutic opportunity to circumvent first-pass processing by direct systemic administration. Circulating esterases could metabolize these NPDs within the systemic compartment, making psilocin directly available for CNS delivery. Also, this holds a notable advantage over directly injecting a psilocin salt due to generally greater aqueous stability observed by most of the NPDs tested (qualitative observation; quantitative stability testing was beyond the scope of this study).

Table 1. In Vitro Metabolic Stability of Psilocybin and Twenty-Eight Novel Prodrug Derivatives (NPDs) upon Exposure to Human Serum and Human S9 and Microsomal Fractions.

|

in vitro Half-life (T1/2) [min] |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NPDa | (aq) | liver S9 fraction | liver microsomes | intestine S9 fraction | intestine microsomes | serum |

| PCB | ∞ | ∞ | ∞ | ∞ | 195.0 | ∞ |

| ES01 | ∞ | 21.0 | 17.0 | 132.0 | 315.0 | 1.0 |

| ES02 | ∞ | 3.0 | 1.0 | 104.0 | 62.0 | 1.0 |

| ES03 | 85.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 56.0 | 32.0 | 0.7 |

| ES04 | ∞ | 529.0 | 390.0 | ∞ | 113.0 | ∞ |

| ES05 | ∞ | 39.0 | 87.0 | 69.0 | 71.0 | 19.0 |

| ES06 | ∞ | ∞ | 241.0 | 445.0 | 621.0 | 101.0 |

| ES07 | 80.0 | 16.0 | 5.0 | 72.0 | 60.0 | 0.8 |

| ES08 | ∞ | 15.0 | 25.0 | 16.0 | 11.0 | ∞ |

| ES09 | ∞ | 3.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 49.0 |

| ES10 | ∞ | 33.0 | 22.0 | ∞ | ∞ | 33.0 |

| C01 | ∞ | 22.0 | 52.0 | 16.0 | 13.0 | 0.8 |

| C02 | ∞ | ∞ | 113.0 | 529.0 | 211.0 | ∞ |

| C03 | ∞ | 9.0 | 4.0 | 327.0 | 271.0 | 3.0 |

| C04 | ∞ | ∞ | 277.0 | 221.0 | 150.0 | 182.0 |

| C05 | 18.0 | 49.0 | 31.0 | 24.0 | 24.0 | 26.0 |

| T01 | ∞ | 5.0 | 6.0 | 50.0 | 71.0 | 14.0 |

| T02 | 6.0 | 7.0 | 9.0 | 24.0 | 13.0 | 32.0 |

| ET01 | ∞ | 60.0 | 27.0 | 64.0 | 50.0 | ∞ |

| EE01 | ∞ | 4.0 | 3.0 | 241.0 | 74.0 | 2.0 |

| EE02 | ∞ | 5.0 | 4.0 | 39.0 | 112.0 | 3.0 |

| EE03 | 145.0 | 16.0 | 13.0 | 52.0 | 22.0 | 0.8 |

| EC01 | ∞ | 293.0 | 104.0 | 266.0 | 894.0 | 3.0 |

| SE01 | ∞ | 191.0 | 347.0 | ∞ | ∞ | ∞ |

| SE02 | ∞ | 96.0 | 104.0 | 57.0 | 27.0 | ∞ |

| SE03 | ∞ | 391.0 | 229.0 | ∞ | ∞ | ∞ |

| P02 | ∞ | 96.0 | 43.0 | 52.0 | 28.0 | ∞ |

| P03 | ∞ | ∞ | ∞ | ∞ | ∞ | ∞ |

| PA01 | 10.0 | 26.0 | 22.0 | 39.0 | 29.0 | 145.0 |

ES = ester; C = carbonate; T = thiocarbonate; ET = ether; EE = ether-esters; EC = ether-carbonate; SE = silyl-ether; P = phosphate; PA = phosphoramidate; PCB = psilocybin; (Aq) indicates that the assay was conducted in aqueous buffer only, minus any biological fraction; and “∞” indicates that compound is stable over the 120-min incubation period.

Table 2. In Vitro Biotransformation of Psilocybin and Twenty-Eight Novel Prodrug Derivatives (NPDs) upon Exposure to Human Serum and Human S9 and Microsomal Fractions after 120 min (μM; End Point Concentration).

| end

point in vitro psilocin concentration [μM] |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NPDa | liver S9 fraction | liver microsomes | intestine S9 fraction | intestine microsomes | serum |

| PCB | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.621 | 0.172 | 0.000 |

| ES01 | 1.950 | 2.718 | 0.114 | 0.041 | 1.097 |

| ES02 | 1.343 | 1.890 | 1.384 | 0.927 | 0.778 |

| ES03 | 1.244 | 2.554 | 0.533 | 0.786 | 0.450 |

| ES04 | 0.145 | 0.329 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| ES05 | 0.689 | 1.310 | 0.000 | 0.018 | 2.010 |

| ES06 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| ES07 | 0.000 | 0.494 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| ES08 | 0.656 | 1.659 | 0.195 | 0.887 | 0.000 |

| ES09 | 0.204 | 0.244 | 0.000 | 0.053 | 0.000 |

| ES10 | 0.451 | 0.919 | 0.166 | 0.241 | 3.148 |

| C01 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| C02 | 0.084 | 0.114 | 0.044 | 0.038 | 0.000 |

| C03 | 1.177 | 1.929 | 0.224 | 0.157 | 0.361 |

| C04 | 0.133 | 0.057 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| C05 | 0.072 | 0.186 | 0.018 | 0.096 | 0.000 |

| T01 | 1.233 | 2.105 | 0.000 | 0.156 | 0.385 |

| T02 | 0.133 | 0.206 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| ET01 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| EE01 | 0.012 | 0.073 | 0.018 | 0.043 | 0.000 |

| EE02 | 0.070 | 0.132 | 0.055 | 0.081 | 0.000 |

| EE03 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| EC01 | 0.186 | 0.056 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| SE01 | 0.000 | 0.012 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| SE02 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.142 |

| SE03 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| P02 | 0.073 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.076 | 0.069 |

| P03 | 0.011 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| PA01 | 0.153 | 0.324 | 0.470 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

ES = ester; C = carbonate; T = thiocarbonate; ET = ether; EE = ether-esters; EC = ether-carbonate; SE = silyl-ether; P = phosphate; PA = phosphoramidate; and PCB = psilocybin.

Contrary to the intended design, a few NPDs, specifically C01 and EE03, which appeared to be efficiently metabolized in some or all fractions tested (Table 1), did not produce any detectable psilocin (Table 2). This is likely due to the generation of alternate or intermediate in vitro metabolites. Interestingly, both C01 and EE03 are modified at indole-NH, which may suggest inappropriate substrate recognition for cleavage of R groups at this site. As the bioanalytical method was developed to evaluate only the loss of the parent NPD and the emergence of the intended psilocin analyte, the intermediate product(s) of these compounds remain unanalyzed. Overall, most NPDs appeared generally stable in aqueous conditions except for C05, T02, and PA01, which show notable T1/2 values under these control conditions lacking any biological fractions (Table 1). Interestingly, each of these novel prodrugs maintains a TIPS-protecting group on the indole-NH. Of note, the results of C05 and T02 are in stark contrast to their respective synthetic counterparts, C03 (carbonate-linked cyclopropyl) and T01 (thiocarbonate-linked benzyl), which lack the TIPS moiety on the indole-NH. These NPDs are stable and are readily metabolized into psilocin in liver- and serum-based fractions. It is important to note that the addition of the TIPS group does not universally generate instability since both compounds ES08 and ES09 remain stable under aqueous conditions and are metabolized into psilocin in various fractions. However, some distinctions in serum metabolism are observed between ES08 and its synthetic counterpart, ES05, suggesting that additional enzymatic steps are required to cleave the TIPS moiety that may not be present in isolated serum fractions. Note that the above evaluation was intended to be a preliminary screen of putative metabolic susceptibility, and we acknowledge that it was not conducted with appropriate replicate analysis. With this in consideration, many NPDs produced robust results, adding some confidence to the downstream hit selection.

Murine Plasma Pharmacokinetics

Metabolic assessment in vitro using subcellular fractions can provide an estimation of first-pass metabolism; however, these fractions do not represent the full enzyme complement of their representative tissues. Furthermore, available methods lack appropriate standardization, making in vitro results only indicative of the true metabolic profile.30 To further evaluate the metabolic characteristics of these NPDs, a selection of molecules observed to produce psilocin in vitro and representing various cleavable motifs described above were chosen for plasma PK analysis in healthy mice (Figure S8). Of note, a carbonate-based NPD C01, which demonstrated appreciable instability in all biological fractions (Table 1) yet did not produce psilocin (Table 2), was also elected as a nonconforming test article for analysis. Each compound was administered intravenously (i.v.) at 1 mg/kg and via oral gavage (per os, p.o.) at 1, 3, and 10 mg/kg. Serial blood samples were evaluated for concentrations of each parent NPD and psilocin over a period of 24 h. As a comparator for PK profiling, psilocybin was also analyzed under the same parameters. Overall, orally dosed NPDs generated a dose-dependent increase in plasma psilocin levels, with some evidence of absorption saturation between 3 and 10 mg/kg dose levels. Each novel prodrug also demonstrated reduced overall psilocin exposure over the measured time frame relative to oral psilocybin.

When dosed at 1 mg/kg i.v., most NPDs produced notable levels of plasma psilocin, reaching maximum concentrations (Cmax) of at least 25% of those detected with psilocybin at the same i.v. dose (Figure 3, Table S1). Indeed, six molecules, ES01, ES02, C02, C03, T01, and EE02, produced psilocin levels approaching or exceeding that derived from psilocybin. Of these, the thiocarbonate-based prodrug, T01, produced a Cmax three to five times greater than psilocybin and maintained an overall systemic exposure of psilocin (AUC(0–tlast)) equivalent to the same dose of psilocybin (Table S1). Interestingly, T01 was one of a number of molecules that proved to be susceptible to serum-based metabolism in vitro (Table 2). This enhanced Cmax may support the suggestion that some of these NPDs may be able to bypass first-pass metabolism when administered systemically. In contrast, psilocin produced from orally administered psilocybin at 1 mg/kg exceeded all NPDs tested by at least 80% (Figure 3, Table S1). This distinction became generally more marginal as the dose level increased to 3 and 10 mg/kg. Notable compounds that proved more amenable to oral administration included two representative carbonate prodrugs, C02 and C03. Both these molecules achieved psilocin Cmax values and AUC(0–tlast) measures comparable to psilocybin at both 3 and 10 mg/kg dose levels. C03 also demonstrated an extended rate of psilocin elimination, or psilocin half-life (T1/2) (Table S1), suggesting that elevated levels of parent prodrug may have been absorbed and metabolized. Interestingly, C02 and C03 contain nonpolar side chains (benzyl and cyclopropyl, respectively) that may increase lipophilicity and contribute to greater absorption when orally administered.37,38 T01 also contains a benzyl prodrug moiety, which may explain the favorable psilocin Cmax and exposure at higher oral dose levels. Similarly, ester-linked aryl derivatives ES03 and ES04 also produce slightly greater psilocin bioavailability upon oral administration. Indeed, a previously reported approach involving the addition of nonpolar l-valine, l-isoleucine, and l-phenylalanine esters to positively charged guanidino-containing molecules significantly enhanced the enteric permeability of these compounds, ultimately enhancing oral delivery.39 In line with this potential for enhanced permeability, many of the NPDs were detected as circulating unmetabolized parent prodrugs after oral delivery, a property not observed at any oral dose of psilocybin (Figure S9). Future studies involving cell-based permeability and further expanded in vivo absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) will confirm the enteric absorption potential for the NDPs elected for further development.

Figure 3.

Pharmacokinetic (PK) analysis of plasma psilocin concentration and measurable psilocin exposure was evaluated in healthy C57BL/6 mice dosed with a single administration of psilocybin or an NDP. LC-MS-based quantification of resultant psilocin metabolite was performed at time points 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 24 h post dose. An additional serial sample was collected at 5 min for animals dosed i.v. (A) Maximum plasma concentration (Cmax) achieved after administration of each prodrug compound is plotted for 1 mg/kg (i.v.) and 1, 3, and 10 mg/kg (p.o). (B) Measurable plasma psilocin exposure (AUC(0–tlast)) achieved after administration of each prodrug compound is plotted for 1 mg/kg (i.v.) and 1, 3, and 10 mg/kg (p.o). n = 3 mice for all dose groups analyzed.

As discussed above, alteration to the cleavable prodrug moiety of psilocybin is predicted to produce variability in the metabolic profile of each NPD, ultimately modifying its PK and overall bioavailability. When dosed orally at both 3 and 10 mg/kg, psilocybin produces notably elevated psilocin Cmax (52.9 ± 6.03 and 243.0 ± 25.2 ng/mL) and significantly enhanced psilocin exposure AUC(0–tlast) (84.4 ± 6.24 and 397.3 ± 31.9 h*ng/mL) (Table S1). These metabolic characteristics lead to measurable levels of plasma psilocin detectable up to 24 h postadministration at both these oral dose levels (Figure S8). Two carbonate-based prodrugs, C02 and C03, which maintain Cmax and AUC(0–tlast) values comparable to psilocybin (Table S1, Figure S8), also demonstrate detectable psilocin at 24 h postdose when administered at 10 mg/kg. However, no other NPD produced detectable levels of psilocin when measured beyond 8 h after oral dosing, even when dosed as high as 10 mg/kg (p.o.). In fact, except for C02 and C03, even when plasma levels of psilocin exceed those derived from psilocybin, the active metabolite is eliminated notably more quickly (Figure 4). These results strongly suggest that derivatization of the cleavable moiety at the 4-OH position does have a markedly prominent effect on the metabolic profile of these compounds. Variation at this position may potentially alter various pharmacological parameters such as absorption of parent molecules, physiological compartments for metabolic processing, and elimination of the psilocin metabolite.

Figure 4.

Comparison of plasma psilocin concentration profiles for (A) ES01, (B) ES04, and (C) T01 dosed at 10 mg/kg relative to psilocybin (PCB) dosed at either 3 mg/kg (top plots) or 10 mg/kg (bottom plots). LC-MS-based quantification of psilocin metabolite was performed at time points 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 24 h post-oral administration.

Overall, in vitro metabolic profiles generally conformed to the in vivo PK profiles for plasma psilocin, with the notable exception being psilocybin. It has been well documented that alkaline phosphatase (AP), which is considered the main enzyme contributing to the dephosphorylation of psilocybin postabsorption (see Figure S3),4,17,25,26 is reported to be anchored to cellular plasma membranes in various tissues throughout the body.40−44 This membrane-localized feature of AP could explain the persistent stability of psilocybin when incubated in cell-free biological fractions in vitro (see Tables 1, 2 and Figure S3) since these fractions are free of plasma membrane fragments. These data may also suggest that soluble esterases, known to be prevalent in these specific biological fractions, may not play a profound role in the metabolism of psilocybin.

Head-Twitch Response Behavioral Analysis

The head-twitch response (HTR) test in mice has proven to be a reliable behavioral proxy for the psychedelic activity produced by hallucinogenic drugs in humans.45−48 HTR, a rapid and involuntary side-to-side rotational head movement, is a distinct behavior induced in rodents upon exposure to psychedelic 5-HT2A receptor agonists. Importantly, the degree of HTR has been shown to be strongly correlated to the psychoactive potency of administered hallucinogens, demonstrating significant predictive validity in this model. For our purposes, we employed the HTR mouse model to assess the functional bioavailability of systemic psilocin. There is strong translational precedence for this, as it has been demonstrated in rodents, pigs, and humans that plasma psilocin levels positively correlate with 5-HT2A receptor occupancy and potency of the psychedelic response.29,49,50 Notably, positron emission tomography (PET) scans of healthy human volunteers treated with the 5-HT2A receptor agonist radioligand [11C]Cimbi-36 demonstrated strong dose-dependent receptor occupancy trends, suggesting a single-site binding model for receptor engagement. These molecular data also correlated to subjective intensity ratings supporting the pharmacodynamic data. These reports suggest that varying levels of NPD-derived psilocin can be relatively determined as measures of HTR intensity, which can translate to the overall prodrug metabolic efficiency in vivo. The same selection of NPDs assessed for their PK properties was further evaluated for psychedelic potency in healthy naïve mice at a well-tolerated oral dose of 1 mg/kg (p.o.). Psilocybin was also included in this test as an appropriate comparator. Figure 5A presents the HTR profile for mice orally dosed with 1 mg/kg psilocybin. Relative to the vehicle, psilocybin produced statistically enhanced HTR up to 90 min postadministration, with a peak intensity occurring within the 15–30 min observation window. This profile closely correlates with the systemic levels of psilocybin-derived psilocin, which reaches a plasma Cmax within this 15-min window (see the kinetic plasma psilocin plot for PCB, Figure S8). For screening purposes, this 15 min observation window was used to assess the HTR induced by each NPD dosed at the same level. Overall, when monitored at the time frame producing peak PCB-inducing HTR (15–30 min), ten of the NPDs assayed produced statistically significant HTR above the vehicle-treated baseline, demonstrating their potential as effective prodrugs (Figure 5B). Interestingly, three ester-based prodrugs (ES01, ES02, and ES03) induced HTR at an intensity statistically equivalent to the natural psychedelic compound, even though they produced peak plasma psilocin concentrations approximately five times lower than oral psilocybin (Table S1). Two additional NPDs, T01 (thiocarbonate) and SE01 (silyl-ether), also induced notable HTR while producing lower peak psilocin levels. These significant findings also point to a potential improvement in the process of absorption for these NPDs, possibly due to the GI stability of the cleavable linkers and the chemical nature of their nonpolar, aromatic side chains. These modified properties improve acute bioavailability and may lead to more efficient and predictable psychedelic responses, ultimately improving therapeutic application. Interestingly, most of these highlighted NPDs showed HTR results consistent with their respective in vitro and PK analyses. This consistency suggests that these tests have the potential to predict physiological responses for the molecules in this class. Additionally, the carbonate-based NPD C01, with unfavorable in vitro and PK results, was also confirmed to be ineffective in inducing HTR. In contrast, the silyl-ether-based NPD, SE01, appears to have performed more favorably than the in vitro and PK data would have predicted, while NPDs, ES04, C03, and EE01, each with in vitro and/or PK data suggestive of potent HTR outcomes, in fact, appeared not to induce a notable hallucinogenic effect. Indeed, due to the subtle nature of this behavioral biomarker, as well as the transient incidence of the neuroactive effects, future studies evaluating the expanded HTR profile over a period of time would allow us to better characterize the kinetic relationship between PK and PD for these NPDs. Overall, these outcomes demonstrate that the appropriate assessment of a novel psychoactive entity requires a multimodal approach to effectively ascertain true biofunctionality.

Figure 5.

Evaluation of head-twitch response (HTR) in healthy C57BL/6 mice dosed with a single administration of psilocybin or an elected set of NPDs at 1 mg/kg (p.o.). (A) Plot presents the time course of HTR in mice orally dosed with 1 mg/kg psilocybin relative to mock-treated mice over a period of 120 min. HTR counts are plotted as the number of counts per 15-min intervals and are marked on the plot at the end of the represented measurement period (n = 4 mice in the psilocybin group, n = 3 mice in the vehicle group). (B) Plot presents the HTR count for the 15–30-min interval for mice treated with a single oral dose of vehicle, PCB, or an NPD at 1 mg/kg (n = 4 mice in the PCB group, n = 2 mice in all remaining groups). Statistical analysis conducted using ordinary one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA): **** p ≤ 0.0001, *** p ≤ 0.001, ** p ≤ 0.01, and * p ≤ 0.05.

Marble-Burying Model for Anxiolytic Potential

Numerous psychiatric mouse models have been developed to study anxiety and depression disorders.48,51,52 Many of these models have successfully demonstrated translational validity in the study of human neuropathology and therapeutic intervention. As critical as these in vivo models are for the development of novel psychotherapeutic treatments, there has also been some skepticism in their application due to the more complicated cognitive and emotional spectrum inherent in human neuropsychology. Additionally, there is the potential for overattributing innate behavioral characteristics, like burrowing and digging, as proxies of anxious behavior.53,54 For example, the marble-burying test (MBT), regularly adopted as a model of anxiety and compulsive behaviors, has been successfully used to predict anxiolytic or anticompulsive pharmacological potential.55−62 In fact, it has been presented that obsessive burying behavior directed at specific sources of aversive or threatening stimuli may be a defensive activity driven by a state of anxiety created by these noxious objects.63 However, the activity of burrowing and nest building has also been used as an indicator of well-being in mice.64 Due to this potential ethological caveat, it has been strongly suggested that contextually valid experimental designs are needed to strengthen the translational value of studies like MBT.53 To this end, the application of a chronic stress paradigm, used to evoke extended hedonic deficit and other depressive-like symptoms in rodents, such as reduced motivation, increased aggression, anxiety, and overall reduction in well-being, is widely considered to have significant etiological relevance and can serve as a valid preclinical model for various human psychiatric disorders.65−78

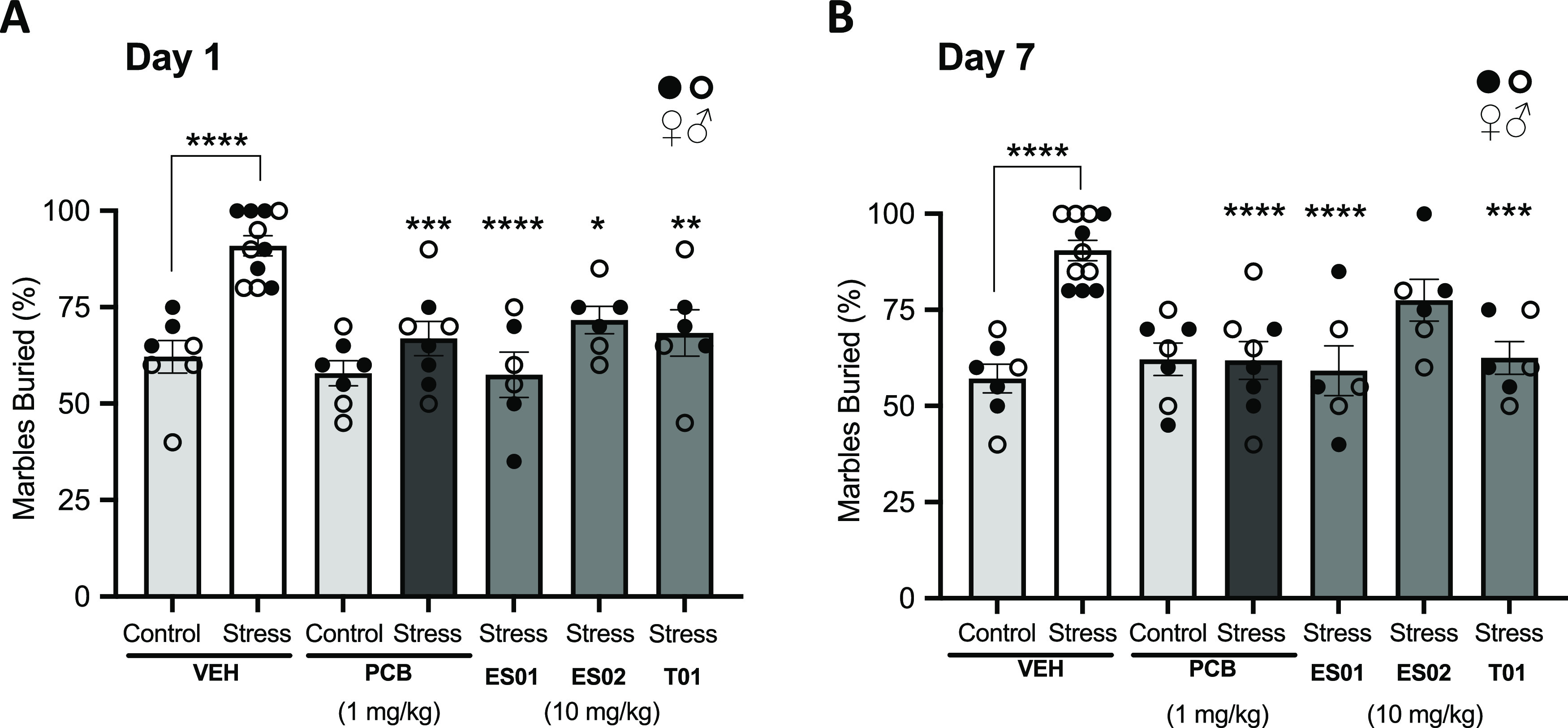

To appropriately assess the anxiolytic potential of our NPDs, we developed a seven-day mild chronic stress paradigm (MCSP) involving a combined oral corticosterone exposure (25 μg/mL introduced into drinking water for 7 days) with a daily 30-min restraint stress session using a ventilated restrainer for the last 5 days of the protocol. It has been shown by others that the combination of these stress-inducing methods leads to more severe depression and anxiety-like behaviors, producing an earlier onset of cognitive deficit in conditioned mice.76 Indeed, when evaluated using the MBT, mice subjected to the MCSP exhibited a significant increase in marble-burying behavior over the unstressed (control) group (Figure 6). This stress conditioning did not produce any noticeable gender bias. Interestingly, this elevated level of stress persisted to the same extent 7 days after MCSP conditioning. Several clinical studies have reported the successful treatment of severe anxiety after a single oral dose of psilocybin, especially in patients struggling with cancer-related distress (CRD).13,79,80 As a demonstration of relevant anxiolytic efficacy in our model, mice subjected to MCSP were treated with a single oral dose of 1 mg/kg psilocybin and assessed for induced marble-burying behavior (Figure 6). Psilocybin treatment resulted in a significantly reduced number of buried marbles by chronically stressed mice, completely returning them to their innate behavioral state, with long-term benefits lasting up to 7 days post-treatment. Consistent with this result, Hesselgrave et al. (2021)81 reported robust recovery of anhedonic responses in mice subjected to an analogous chronic stress paradigm and treated with a single dose of psilocybin 24 h prior to behavioral assessment using the sucrose preference test and female urine sniffing test. They also noted that stress-resilient mice, with no induced anhedonic responses, did not display loss of sucrose preference, and observation supported by Matsushima et al. (2009)82 using the MBT. Interestingly, our data also show that psilocybin has no significant effect on the innate burying behavior in nonstressed mice (Figure 6). These combined results, demonstrating antidepressive and/or anxiolytic effects only occur in behaviorally deficient mice, strongly suggest that the therapeutic value of psilocybin lies in the recovery of a physical neurological deficiency induced by the MCSP and not in an acute pharmacological alteration of perception. Indeed, this conclusion has also been reported by Hesselgrave et al. (2021),81 who have extended their analyses to reveal that psilocybin works through a specific mechanism of action to restore hippocampal synaptic strength in chronically stressed mice. This neuronal repair is strongly correlated to the recovery of anhedonia seen in these conditioned animals.

Figure 6.

Results for the marble-burying test (MBT) in mice subjected to a Mild Chronic Stress Paradigm (MCSP) and treated with a single dose of vehicle, psilocybin (PCB), at 1 mg/kg (p.o.), and the NPDs ES01, ES02, and T01 each at 10 mg/kg (p.o.). Plots present % marbles buried over a 20 min exposure period measured on (A) Day 1 (24 h) and (B) Day 7 (168 h) postadministration. Statistical analysis conducted using ordinary one-way ANOVA: **** p ≤ 0.0001, *** p ≤ 0.001, ** p ≤ 0.01, and * p ≤ 0.05 (n = 7 mice for vehicle and psilocybin nonstress groups, n = 11 mice for vehicle stress group, n = 8 mice for psilocybin stress group, n = 6 mice for NPD stress groups).

Three NPDs, ES01, ES02, and T01, which demonstrated efficient prodrug properties and notable bioactivity, were elected for evaluation of anxiolytic potential using the MBT in mice subjected to the MCSP. To normalize the acute exposure of psilocin relative to that produced by 1 mg/kg oral psilocybin, each NPD was dosed orally at 10 mg/kg. All three NPDs tested induced a significant reduction in marble-burying behavior in stressed mice at 1-day postdose (Figure 6). Two of these candidate prodrugs, ES01 (ester-based methoxybenzyl derivative) and T01 (thiocarbonate-based benzyl derivative), produced notable long-term positive outcomes, completely rescuing the elevated anxiety-like condition to the innate behavioral state up to 7 days after treatment. Indeed, overall psilocin exposure may explain these outcomes, with these two prodrugs producing a more sustained level of psilocin with AUC(0–tlast) values greater than twice that of ES02 within the first 8 h after administration.

Discussion and Conclusions

Depression and anxiety disorders affect hundreds of millions of people worldwide and represent a major public health burden (World Health Organization [WHO], 2023). Numerous factors contribute to this global statistic. Current antidepressant and anxiolytic medications remain ineffective for a significant proportion of the afflicted population, demonstrating either eventual relapse or complete treatment resistance.83 Even when effective, antidepressant action of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) often results in reduced limbic responsiveness and emotional blunting.84 Alternatively, psychedelics such as psilocybin promote emotional release and have produced increased and sustained improvements in perceptual outlook, optimism, and overall well-being in patients struggling with severe depression and anxiety disorders.7,8,10−13,79,80 Undesirably, the extended duration of the acute psychoactive effect of psilocybin creates major hurdles to the widespread therapeutic application of this natural psychedelic. Most critically, psilocybin-induced psychotherapy requires significant clinical supervision to ensure patient safety as well as active psychiatric oversight. Nonetheless, there is growing enthusiasm for the therapeutic potential inherent in these natural drugs, which is driving innovation in the development of novel psychedelic-inspired therapies. The goal of the present study was to design a series of novel prodrug derivatives (NPDs) of psilocin that release therapeutically meaningful levels of this psychoactive agent and induce long-term efficacious anxiolytic responses, while maintaining altered pharmacokinetic profiles of plasma psilocin concentration with modified overall exposure.

Chemical Modification at the 4-Position Alters Psilocin Exposure Profile

An established strategy in drug development is to chemically modify pharmacologically active agents into prodrug derivatives to improve a drug’s physiochemical, biopharmaceutical, and pharmacokinetic properties.85 As a natural prodrug of psilocin, psilocybin, by virtue of the phosphate moiety at the indolic 4-OH position, serves as a chemically stabilized form of this psychoactive molecule.24,25,86,87 As a soluble zwitterion, psilocybin maintains limited absorption potential; however, upon oral ingestion, a significant proportion of psilocybin is readily dephosphorylated to the more lipid-soluble psilocin, which is easily absorbed by the large and small intestinal tissues.6,17,27 Additional metabolism by intestinal and liver enzymes further enhances the bioavailability of psilocin.4,17,25,26 The primary objective of this study was to generate a series of NPDs of psilocin with diverse metabolically amendable substitutions at the 4-OH position. To the best of our knowledge, this study represents the first comprehensive evaluation of intentionally designed psilocin prodrug derivatives. Previous studies on the synthesis and characterization of various indole esters revealed 4-acetoxy-N,N-dimethyltryptamine (4-AcO–DMT; psilacetin), as a potential O-acetyl prodrug of psilocin.90,91 To date, this molecule remains fairly uncharacterized; however, reports have suggested that orally ingested 4-AcO–DMT maintains psilocybin-like pharmacological properties.92 We surmised that further modification of 4-OH beyond O-acetyl may generate altered pharmacokinetic profiles that are more amenable to clinical application. When orally dosed, all NPDs produced measurable levels of systemic psilocin (Figure 3, Table S1). Though these plasma psilocin levels are somewhat reduced relative to those of mice dosed with psilocybin, most NPDs generated functionally relevant psilocin concentrations, producing significant and timely stimulation of the 5-HT2A receptor in vivo (Figure 5B). Importantly, when comparing the PK profiles of plasma psilocin levels after a single dose, most NPDs did not produce detectable levels of psilocin beyond 8 h post administration, even in mice dosed as high as 10 mg/kg (p.o.) (Figure S8). Two carbonate-based prodrugs, C02 and C03, were an exception to this observation. Both of these NPDs maintained plasma psilocin Cmax and AUC(0–tlast) values comparable to those induced by psilocybin (Figure 3, Table S1), with levels of plasma psilocin detectable up to 24 h after the 10 mg/kg (p.o.) dose (Figure S8). Notably, many NPDs harboring nonpolar, aromatic side chains (e.g., C02, T01, and ES04) produced more systemic psilocin relative to the aliphatic and charged derivatives. This result suggests that these more favorable NPDs may possess potentially greater intestinal absorption properties. Additionally, it can be argued that the reduced level of plasma psilocin relative to that derived by an equivalent dose of psilocybin may suggest a greater GI stability of the orally dosed NPDs. This enhanced stability would simplify the metabolic process, limiting psilocin production to postabsorption bioprocessing, which may prove to be a highly advantageous parameter. A commonly reported acute adverse effect of ingesting psilocybin is nausea, vomiting, and occasional abdominal pain.7,9,11,88 Although the exact cause for this negative GI effect has not been appropriately elucidated, it is thought to be due to the rapid hydrolysis of psilocybin into the bioactive agent psilocin within the acidic lumen of the GI tract. Interestingly, serotonin signaling within the GI is a physiologically important function, and the majority of serotonin is synthesized, stored, and released by enteroendocrine cells within the intestinal mucosa.89 Indeed, signals stimulating the perception of nausea and enteric pain are among the many effects of serotonin signaling within the GI. Hence, it may be reasonable to suggest that the presence of serotonergic psilocin following ingestion of psilocybin may have the potential to stimulate these reactive centers in the gut lining, inducing similar sensations of GI distress. As such, establishing greater GI stability and designing a metabolic mechanism reliant on postabsorption conversion would generate a notable therapeutic advantage by potentially reducing the adverse GI effects and producing a more acute systemic psilocin exposure.

NPDs Generating Bioavailable Psilocin Stimulate Psychoactive Responses in Mice

Psychedelic-induced head-twitch response (HTR) in rodents has been reliably used as a behavioral pharmacodynamic biomarker of 5-HT2A receptor stimulation and a proxy for psychoactive potential.47,48 In fact, it has been shown that plasma levels of psilocin strongly correlate to the intensity of this psychomimetic behavior, indicating that systemic exposure of psilocin can be an indicator of CNS bioavailability.49 Among the NPDs, orally dosed ester- and thiocarbonate-based derivatives produced the most potent HTR in healthy mice (Figure 5). ES01 and ES03, in particular, produced HTR responses equivalent to psilocybin. Overall, these compounds reliably produced favorable in vitro and in vivo metabolic profiles relative to other NPDs, making these tests highly predictive of the intended behavioral outcome (Tables 1 and 2, Figure S8). It is important to note that relative to psilocybin, each of these compounds produced less than 20% of the maximum psilocin concentration (Cmax) and exposure (AUC(0–tlast)) when dosed orally at 1 mg/kg. However, each was able to induce a psychoactive response statistically relevant to the natural prodrug. In contrast to the ester and thiocarbonate results, two silyl-ether-based NPDs, SE01 and SE02, also induced notable HTR, although these compounds did not produce favorable metabolic profiles, with plasma psilocin levels at 7 and 1% that of an equivalent dose of psilocybin, respectively. These molecules, in fact, proved to be quite stable in vivo, with significant systemic levels of the parent derivatives detected up to 8 h postdose (Figure S9). This observation strongly suggests that the parent molecules for SE01 and SE02 may in fact be novel chemical entities with psychoactive properties of their own. Further investigation will be performed to characterize the biodistribution and functional nature of these parent NPDs. Specific attention will be paid to CNS exposure and distinctions in the stimulation of key serotonergic receptors known to have therapeutic benefits, such as 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A.

Within our library of NPDs, a few analogous compound pairs harboring the same pendant linked by different cleavable moieties were generated. As an example, the carbonate-based compound C02 and the thiocarbonate-based compound T01 both carry a benzyl side chain R group (Figure 2). Interestingly, both of these prodrugs performed differently when subjected to in vitro metabolism. T01 maintained a much shorter half-life (T1/2) in each of the biological fractions tested compared to C02 (Table 1). Correspondingly, much greater psilocin was generated by T01, with a significant preference for liver-based in vitro metabolism (Table 2). In contrast to the variation seen in vitro, these two NPDs maintained very similar in vivo metabolic profiles, with both compounds producing notable levels of plasma psilocin, maintaining very similar overall psilocin exposure (Figure 3, Table S1), and producing statistically significant psychomimetic effects in healthy mice (Figure 5). Of note, T01 performed more favorably upon intravenous administration, producing approximately seven times greater psilocin compared to C02 and approximately four times greater psilocin relative to the natural prodrug at the same dose. This may suggest that the thiocarbonate linker in T01 may be very susceptible to cleavage by circulating serum esterases, increasing the rate of psilocin generation relative to that of the other NPDs.

NPDs Retain Anxiolytic Benefit in Chronically Stressed Mice

Alteration of the cleavable linker in a prodrug has profound effects on the metabolic profile of the modified compound. Changing the linker to attract a different target enzyme may not only diversify the stability of the molecule delivered by different routes of administration but also alter the compartment responsible for the metabolic conversion of the prodrug. Psilocybin is known to be readily hydrolyzed in the acidic gastric compartment, releasing a significant level of psilocin prior to initial absorption.6,17,23,24,26 Our data have demonstrated that the substitution of an ester- or thiocarbonate-based linker at the same 4-carbon position enhances liver-based metabolic processing of these compounds. Two notable NPD candidates that exemplify this altered metabolic profile are ES01, an ester-based methoxybenzyl derivative, and T01, a thiocarbonate-based benzyl derivative. Additionally, due to the lower levels of plasma psilocin produced when NPDs are orally dosed (Figure S8), our results may imply a potentially greater stability in the GI lumen relative to psilocybin. This can be inferred from the fact that free psilocin has very favorable absorption properties. If orally dosed NPD was converted to psilocin within the intestinal lumen, we would potentially see psilocin levels equivalent to psilocybin, specifically the extended systemic exposure seen from psilocybin dosed at 3 and 10 mg/kg (p.o.) (Figure 4). This extended exposure is likely due to the continual absorption of psilocin as the intestinal reservoir of psilocybin hydrolyzes as it moves along the lower GI tract. Hence, GI stability of NPDs creates a greater reliance on postabsorption metabolic processing, likely limited to the small intestinal compartment, and potentially a more mediated acute psilocin exposure relative to psilocybin. Comprehensive absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) studies of ES01 and T01 will help support this hypothesis. Despite significant alteration to the pharmacokinetic profiles of these NPDs, fast-acting and sustained anxiolytic benefits are retained by these candidate prodrugs, highlighting their potential as valid therapeutic agents. Indeed, these novel prodrugs achieve efficacy comparable to psilocybin at dose-normalized levels (Figure 6). However, when dosed at higher levels, most NPDs maintain reduced overall exposure of psilocin compared to psilocybin, which may suggest a potentially reduced period of psychoactive effect while maintaining the associated long-term benefits. A shorter and more predictable exposure profile would have a significant clinical benefit by reducing the overall burden inherent in medical supervision and prolonging psychotherapeutic oversight. Though this needs to be fully explored and may only be appropriately determined by human trial, the current study demonstrates the potential of using modified prodrug derivatives of psilocin to treat anxiety and depression. These newly described NPDs have the promise to dramatically improve the clinical application of psilocin as a therapeutic agent, offering alternative small-molecule pharmaceutical entities that are able to address current, treatment-resistant mental disorders.

Experimental Section

General Chemistry Information

All reactions were performed under an argon or nitrogen atmosphere in flame-dried glassware and dried solvents at room temperature unless stated otherwise. Controlled temperature reactions were performed by using a mineral oil bath or aluminum heating blocks and a temperature-controlled hot plate (IKA Ceramag Midi). Temperatures below room temperature were achieved in an ice/water bath (0 °C), dry ice/ethylene glycol bath (−20 °C), dry ice/ethanol/ethylene glycol bath (−20 to −75 °C), and dry ice/isopropanol bath (−78 °C). Solvents were removed under reduced pressure by using a Büchi rotary evaporator. Anhydrous solvents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich or prepared by distillation under a nitrogen atmosphere or drying over 3 or 4 Å molecular sieves for at least 48 h. All reagents and solvents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, Combi-Blocks, Thermo Fisher, A2B Chemicals, Enamine, Oakwood Chemicals, or Ambeed unless stated otherwise. Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) was performed using silica gel 60 F254 precoated glass-backed plates. Detection of TLC spots was performed using a hand-held UV lamp at 254 nm or by staining with potassium permanganate prepared according to the literature procedure. Flash column chromatography purifications were performed using silica gel 60 (230–400 mesh, SiliCycle, Quebec) on automated Combi-Flash Teledyne NextGen 300 systems. Low-resolution mass spectra (LRMS) in heated electrospray ionization (HESI) mode were obtained from a Thermo Fortis triple quadrupole (3Q) system. High-resolution mass spectra (HRMS) in the HESI mode were obtained from a Thermo LC-LTQ-Orbitrap-XL system. Proton (1H NMR) spectra were obtained using Bruker RDQ-400 or DRY-400 (400 MHz) spectrometers. The purity of the final products submitted for biological testing was determined by 1H NMR to be ≥95%. For the NMR spectrum of all final products, see the Supporting Information.

2-(4-(Benzyloxy)-1H-indol-3-yl)-N,N-dimethyl-2-oxoacetamide (4)

A dry, three-neck RBF was charged with 4-benzyloxyindole 2 (14.0 g, 62.7 mmol) and Et2O (327 mL) under Ar. The mixture was cooled down to 0 °C in an ice bath. An argon sparge was placed on the RBF and into the reaction mixture to purge out the HCl gas released from the reaction. Oxalyl chloride (10.9 mL, 129 mmol) was added dropwise over 40 min while maintaining the cold temperature. The mixture was stirred at 0 °C for 4 h. The argon sparge was removed, and dimethylamine (157 mL, 314 mmol) (2 M in tetrahydrofuran (THF)) was added dropwise at 0 °C over 1 h using an addition funnel. The mixture was allowed to warm up to room temperature (RT) and stir overnight. Diethyl ether (200 mL) was added, and the mixture was cooled to 0 °C. The resulting precipitate (crude 3) was filtered and transferred to an Erlenmeyer flask. The solid was suspended in water (300 mL) and stirred for 30 min. Then, it was filtered and washed with more H2O to remove the residual salts. The crude solid was further dried in vacuo to afford 4, which was used in the next step without further purification. LRMS-HESI: calcd for C19H19N2O3 [M + H]+: 323.14; found 323.18. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 10.44 (s, 1H), 7.54 (ddt, J = 7.4, 1.3, 0.7 Hz, 2H), 7.50 (d, J = 3.2 Hz, 1H), 7.42–7.35 (m, 2H), 7.34–7.29 (m, 1H), 7.03 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 6.89 (dd, J = 8.2, 0.8 Hz, 1H), 6.64 (dd, J = 7.9, 0.8 Hz, 1H), 5.25 (s, 2H), 2.96 (s, 3H), 2.91 (s, 3H).

2-(4-(Benzyloxy)-1H-indol-3-yl)-N,N-dimethylethanamine, 4-BnO–DMT (5)

Lithium aluminum hydride (2 M in THF, 60.2 mL, 120 mmol) was added to a dry 3-neck flask under argon. The flask was fitted with a reflux condenser and an addition funnel. Dry 1,4-dioxane (100 mL) was added, and the mixture was heated to 60 °C in an oil bath. In a separate flask, compound 4 (7.46 g, 23.1 mmol) was dissolved in a mixture of THF (60 mL) and 1,4-dioxane (120 mL). This solution was added in a dropwise manner to the rapidly stirring LiAlH4 solution over 1 h using an addition funnel. The oil bath temperature was held at 70 °C for 4 h, followed by vigorous reflux overnight (16 h) at an oil bath temperature of 95 °C. The reaction mixture was placed in an ice bath, and a solution of distilled H2O (25 mL) in THF (65 mL) was added dropwise to quench LiAlH4, resulting in a gray flocculent precipitate. Et2O (160 mL) was added to assist in the breakup of the complex and improve filtration. This slurry was stirred for 1 h, and the mixture was then filtered using a Buchner funnel. The filter cake was washed on the filter with warm Et2O (2 × 200 mL) and was broken up, transferred back into the reaction flask, and vigorously stirred with additional warm Et2O (300 mL). This slurry was filtered, and the cake was washed with Et2O (120 mL) and hexane (2 × 120 mL). All of the organic filtrates were combined and dried (MgSO4). After the drying agent was removed by filtration, the filtrate was concentrated under vacuum and dried under high vacuum. The crude residue was triturated with EtOAc/hex (1:9, 25 mL) to afford the crude product (5) that was used in the next step without further purification. LRMS-HESI: calcd for C19H23N2O [M + H]+: 295.18; found 295.19. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.04 (s, 1H), 7.52 (dtd, J = 7.2, 1.4, 0.6 Hz, 2H), 7.39 (tt, J = 6.5, 1.0 Hz, 2H), 7.35–7.31 (m, 1H), 7.11–7.02 (m, 1H), 6.97 (dd, J = 8.2, 0.8 Hz, 1H), 6.90 (dd, J = 2.0, 1.0 Hz, 1H), 6.56 (dd, J = 7.7, 0.8 Hz, 1H), 5.21 (s, 2H), 3.11–3.02 (m, 2H), 2.65–2.56 (m, 2H), 2.16 (s, 6H).

3-(2-(Dimethylamino)ethyl)-1H-indol-4-ol, Psilocin (1)

To a stirring solution of 5 (2.00 g, 6.79 mmol) in ethanol (106 mL) under argon was added palladium on carbon (10 wt %, 723 mg, 0.679 μmol). The vessel was evacuated and backfilled with H2 gas three times, and then a balloon of H2 was left attached to the vessel. The reaction mixture was allowed to stir at room temperature for 75 min. Anhydrous MgSO4 was added to remove water, and the mixture was filtered over Celite. The filtrate was concentrated under reduced pressure to yield a brown solid. Purification by flash column chromatography on silica gel (MeOH/dichloromethane (DCM) 0:100 to 18:82) yielded the pure product 1 (psilocin) as a tan solid (530 mg, 38%). Alternatively, the crude product was used in the next step without further purification (80–85% purity). LRMS-HESI: calcd for C12H17N2O [M + H]+: 205.13; found 205.15. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.27 (s, 1H), 7.05 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 6.85 (dd, J = 8.1, 0.9 Hz, 1H), 6.81 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H), 6.59 (dd, J = 7.6, 0.9 Hz, 1H), 2.96–2.92 (m, 2H), 2.72–2.68 (m, 2H), 2.36 (s, 6H).

2-(4-(Benzyloxy)-1-(triisopropylsilyl)-1H-indol-3-yl)-N,N-dimethylethanamine, 4-BnO-TIPS-DMT (6)

To a solution of 5 (5.00 g, 17.0 mmol) in dry THF (100 mL) cooled to −78 °C under argon was added dropwise a 1 M solution of KHMDS (18.7 mL, 18.7 mmol) in THF. After stirring at −78 °C for 1 h, a solution of TIPSCl (3.82 mL, 17.8 mmol) in THF (19.0 mL) was added dropwise over 15 min, and the reaction mixture was allowed to warm up to RT. After stirring at RT for 1 h, the reaction mixture was quenched with H2O (40 mL), THF was evaporated under reduced pressure, and the aqueous solution was further diluted with H2O (75 mL) and extracted with DCM (3 × 100 mL). The organic layers were combined and washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude product was purified by flash column chromatography on silica gel (MeOH/DCM 5:95 to 10:90) to afford the pure product 6 as a light-brown oil (6.99 g, 91%). LRMS-HESI: calcd for C28H43N2OSi [M + H]+: 451.31; found 451.37. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.58–7.51 (m, 2H), 7.44–7.39 (m, 2H), 7.38–7.33 (m, 1H), 7.12 (dd, J = 8.4, 0.8 Hz, 1H), 7.08–6.99 (m, 1H), 6.94 (s, 1H), 6.60 (dd, J = 7.7, 0.7 Hz, 1H), 5.20 (s, 2H), 3.12–3.04 (m, 2H), 2.67–2.58 (m, 2H), 2.16 (s, 6H), 1.69 (h, J = 7.5 Hz, 3H), 1.16 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 18H).

3-(2-(Dimethylamino)ethyl)-1-(triisopropylsilyl)-1H-indol-4-ol, N-TIPS-Psilocin (7)

To a stirring solution of 6 (6.99 g, 15.5 mmol) dissolved in EtOH, 95% (310 mL) was added palladium on carbon (10 wt %, 1.65 g, 1.55 mmol). This mixture was put under vacuum for five min, then alternately purged with H2 gas until a pressurized hydrogen atmosphere was established, and then allowed to stir for 75 min at room temperature. The palladium on carbon was removed by filtration through Celite, and the filtrate was dried with anhydrous MgSO4 and concentrated under reduced pressure to yield 7 (4.67 g, 84%) as an off-white solid. HRMS-HESI: calcd for C21H37N2OSi [M + H]+: 361.2670; found 361. 2668. 1H NMR (400 MHz, MeOD) δ 6.98 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 6.91 (dd, J = 8.4, 7.5 Hz, 1H), 6.42 (dd, J = 7.5, 0.8 Hz, 1H), 3.06 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H), 2.77 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H), 2.39 (s, 6H), 1.72 (p, J = 7.5 Hz, 3H), 1.16 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 18H).

3-(2-(Dimethylamino)ethyl)-1H-indol-4-yl 4-Methoxybenzoate (ES01)

A solution of psilocin 1 (200 mg, 979 μmol) and triethylamine (274 μL, 1.96 mmol) in DCM (8.0 mL) was cooled to 0 °C. To this was added 4-methoxybenzoyl chloride (192 mg, 1.12 mmol) in DCM (0.5 mL). The resulting mixture was warmed up to RT and stirred for 2 h. At this time, another portion of 4-methoxybenzoyl chloride (192 mg, 1.12 mmol) in DCM (0.5 mL) was added, and the reaction mixture was stirred at RT for another hour. Methanol (2 mL) was added to the reaction mixture, and the volatiles were removed in vacuo. The crude residue was directly purified by flash column chromatography on silica gel (MeOH/DCM 0:100 to 20:80) to afford the product as a brown oil. TLC showed coelution of p-methoxybenzoic acid with the product. This isolated material was redissolved in DCM (50 mL) and extracted with saturated aqueous NaHCO3 (2 × 30 mL). The aqueous layer was back extracted with DCM (×1), washed with brine, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated to afford the pure product (ES01) as an off-white foamy solid (245 mg, 74%). LRMS-HESI: calcd for C20H23N2O3 [M + H]+: 339.17; found 339.16. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.27–8.21 (m, 3H), 7.23 (dd, J = 8.2, 1.0 Hz, 1H), 7.17 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.03–6.98 (m, 2H), 6.95 (dd, J = 2.3, 1.1 Hz, 1H), 6.88 (dd, J = 7.6, 1.0 Hz, 1H), 3.90 (s, 3H), 2.92–2.84 (m, 2H), 2.60–2.52 (m, 2H), 2.09 (s, 6H).

3-(2-(Dimethylamino)ethyl)-1H-indol-4-yl 2-cyclopropylacetate (ES02)

A solution of psilocin 1 (600 mg, 2.94 mmol) and triethylamine (823 μL, 5.87 mmol) in anhydrous DCM (29.4 mL) was cooled down to 0 °C. To this was added cyclopropylacetyl chloride (813 μL, 8.22 mmol, 2.8 equiv) in 3 portions (1.2 equiv + 1.2 equiv + 0.4 equiv; with 2 h intervals), and the resulting mixture was warmed up to RT and stirred overnight. After 18 h, TLC (MeOH/DCM 20:80) showed full consumption of psilocin. The reaction mixture was quenched with methanol (1 mL), and the volatiles were removed in vacuo. The crude residue was directly purified by flash column chromatography on silica gel (MeOH/DCM 0:100 to 20:80) to afford the product as a brown oil. 1H NMR showed coelution of cyclopropylacetic acid with the product. The isolated material was redissolved in DCM (25 mL) and extracted with saturated aqueous NaHCO3 (1 × 25 mL). The aqueous layer was back extracted with DCM (2 × 30 mL), washed with brine, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated to afford the pure product ES02 as a tan solid (510 mg, 61%). HRMS-HESI: calcd for C17H23N2O2 [M + H]+: 287.1760; found 287.1753. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.20 (s, 1H), 7.18 (dd, J = 8.2, 1.0 Hz, 1H), 7.12 (dd, J = 8.2, 7.5 Hz, 1H), 6.94 (dt, J = 2.2, 1.0 Hz, 1H), 6.81 (dd, J = 7.5, 1.0 Hz, 1H), 2.98–2.86 (m, 2H), 2.64–2.55 (m, 4H), 2.30 (s, 6H), 1.32–1.17 (m, 1H), 0.71–0.59 (m, 2H), 0.31 (dt, J = 6.0, 4.7 Hz, 2H).

3-(2-(Dimethylamino)ethyl)-1H-indol-4-yl 2,3,4,5,6-pentafluorobenzoate (ES03)

To a suspension of psilocin 1 (30 mg, 147 μmol) in dry DCM (8 mL) were added triethylamine (22 μL, 157 μmol) and pentafluorobenzoyl chloride (34.6 μL, 240 μmol). The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 2 h, and the reaction was monitored by TLC. The reaction mixture was then quenched with 0.5 M aqueous HCl and extracted with DCM (×3). The combined organic extracts were washed with water and brine, dried over anhydrous MgSO4, and filtered. The filtrate was concentrated under reduced pressure and purified by flash column chromatography on silica gel (MeOH/DCM 5:95) to provide the product ES03 as an off-white solid (21.2 mg, 36% yield). HRMS-HESI: calcd for C19H16F5N2O2 [M + H]+: 399.1126; found 399.1120. 1H NMR (400 MHz, MeOD) δ 7.39 (dd, J = 8.2, 0.8 Hz, 1H), 7.30 (d, J = 1.0 Hz, 1H), 7.20 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 6.93 (dd, J = 7.7, 0.8 Hz, 1H), 3.41 (dd, J = 7.9, 6.9 Hz, 2H), 3.25–3.13 (m, 2H), 2.84 (s, 6H).

3-(2-(Dimethylamino)ethyl)-1H-indol-4-yl 2,3-dihydrobenzo[b][1,4]dioxine-5-carboxylate (ES04)

To a solution of 1 (74.7 mg, 366 μmol) and N,N-diisopropylethylamine (100 μL, 574 μmol) in DCM (2 mL) was added, in a dropwise manner, a solution of 2,3-dihydrobenzo[b][1,4]dioxine-5-carbonyl chloride (77.2 mg, 373 μmol) in DCM (1 mL). The mixture was left to react at RT. After 3 h, the starting material was mostly consumed, and the reaction mixture was poured into a separatory funnel containing 10 mL of water and 10 mL of DCM. The aqueous phase was extracted with DCM (3 × 10 mL), and all organic phases were combined, washed with brine, and dried over anhydrous MgSO4. After filtration, the solvent was removed under reduced pressure, leaving a beige solid. The crude product was purified by flash column chromatography on silica gel (MeOH/DCM 10:90) to yield the desired product ES04 (68 mg, 51%) as a white solid. HRMS-HESI: calcd for C21H23N2O4 [M + H]+: 367.1652; found 367.1651. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 11.06 (s, 1H), 7.57 (dd, J = 7.8, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.26 (dd, J = 8.1, 0.8 Hz, 1H), 7.20–7.13 (m, 2H), 7.07 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 6.98 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 6.74 (dd, J = 7.6, 0.8 Hz, 1H), 4.38–4.28 (m, 4H), 2.79–2.71 (m, 2H), 2.44 (dd, J = 9.2, 6.7 Hz, 2H), 2.01 (s, 6H).

3-(2-(Dimethylamino)ethyl)-1H-indol-4-yl 4-bromobenzoate (ES05)

To a solution of ES08 (below) (175 mg, 322 μmol) in THF (2.0 mL) was added tetrabutylammonium fluoride (TBAF) (1 M in THF, 483 μL, 483 μmol) dropwise. After 30 min, the mixture was poured into a separatory funnel containing water (15 mL) and DCM (15 mL), the aqueous phase was extracted with DCM (3 × 15 mL), and the combined organic layers were washed with brine, dried over anhydrous MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated. The crude residue was purified by flash column chromatography on silica gel (MeOH/DCM 10:90) to afford the product (ES05) as a white powder (80.0 mg, 64%). HRMS-HESI: calcd for C19H20BrN2O2 [M + H]+: 387.0703; found 387.0704. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.87 (dd, J = 8.2, 0.9 Hz, 1H), 7.66 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.58 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.23 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 6.89 (s, 1H), 6.81 (dd, J = 8.0, 0.9 Hz, 1H), 2.93–2.86 (m, 2H), 2.79–2.73 (m, 2H), 2.42 (s, 6H).

Bis(3-(2-(dimethylamino)ethyl)-1H-indol-4-yl) Isophthalate (ES06)

To a flame-dried flask were added psilocin 1 (50 mg, 0.25 mmol) and anhydrous DCM (1 mL) under argon. Triethylamine (34 μL, 0.25 mmol) was added, followed by isophthaloyl chloride (25 mg, 0.12 mmol) dissolved in anhydrous DCM (1 mL). The mixture was refluxed overnight, then dried in vacuo and directly purified by flash column chromatography on silica gel (MeOH/DCM 10:90 to 20:80) to yield ES06 (19.6 mg, 30%) as a light-brown oil. HRMS-HESI: calcd for C32H35N4O4 [M + H]+: 539.2653; found 539.2645. 1H NMR (400 MHz, MeOD) δ 9.13 (td, J = 1.8, 0.6 Hz, 1H), 8.70 (dd, J = 7.8, 1.8 Hz, 2H), 7.95 (td, J = 7.8, 0.6 Hz, 1H), 7.42–7.37 (m, 2H), 7.29 (t, J = 0.9 Hz, 2H), 7.24–7.18 (m, 2H), 6.93 (dd, J = 7.7, 0.8 Hz, 2H), 3.41–3.36 (m, 4H), 3.20–3.14 (m, 4H), 2.73 (s, 12H).

3-(2-(Dimethylamino)ethyl)-1H-indol-4-yl 2-(2-(2-methoxyethoxy)ethoxy)acetate (ES07)

Compound 1 (100 mg, 0.49 mmol) was suspended in anhydrous DCM (0.5 mL) under an argon atmosphere. Triethylamine (0.10 mL, 0.73 mmol) was added, followed by m-PEG2-CH2 acid chloride (96 mg, 0.49 mmol) diluted in DCM (0.2 mL). The resulting mixture was stirred at room temperature for 23 h and monitored by TLC (20% MeOH/DCM). The volatiles were removed under reduced pressure, and the crude residue was directly purified by flash column chromatography on silica gel (12 g, 10% MeOH/DCM). The resulting semipure product was further purified by a second flash column chromatography on silica gel (MeOH/DCM 8:92 to 10:90) to yield ES07 (3.9 mg, 2.2%) as a colorless oil. HRMS-HESI: calcd for C19H29N2O5 [M + H]+: 365.2071; found 365.2068. 1H NMR (400 MHz, MeOD) δ 7.32 (dd, J = 8.2, 0.8 Hz, 1H), 7.27 (s, 1H), 7.15 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 6.88 (dd, J = 7.8, 0.8 Hz, 1H), 4.58 (s, 2H), 3.92–3.85 (m, 2H), 3.78–3.72 (m, 2H), 3.70–3.64 (m, 2H), 3.59–3.52 (m, 2H), 3.48–3.42 (m, 2H), 3.37 (s, 3H), 3.26–3.17 (m, 2H), 2.94 (s, 6H).

3-(2-(Dimethylamino)ethyl)-1-(triisopropylsilyl)-1H-indol-4-yl 4-Bromobenzoate (ES08)

To a solution of N,N-diisopropylethylamine (114 μL, 653 μmol) and 7 (150 mg, 416 μmol) in DCM (2.50 mL) was added in a dropwise manner a solution of 4-bromobenzoyl chloride (93.2 mg, 416 μmol) in DCM (1.25 mL). The mixture was left to react at RT. After 3 h, the mixture contained very little starting material, and the reaction mixture was poured into a separatory funnel containing 10 mL of water and 10 mL of DCM. The aqueous phase was extracted with DCM (3 × 10 mL), and all organic phases were combined, washed with brine, and dried over MgSO4. Purification was carried out by flash column chromatography on silica gel (MeOH/DCM 10:90) to afford ES08 (193 mg, 85%) as a colorless oil. HRMS-HESI: calcd for C28H40BrN2O2Si [M + H]+: 543.2037; found 543.2036. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.15 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 7.68 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 7.38 (dd, J = 8.3, 0.8 Hz, 1H), 7.17–7.10 (m, 1H), 7.02 (s, 1H), 6.90 (dd, J = 7.7, 0.7 Hz, 1H), 2.96–2.85 (m, 2H), 2.59 (t, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 2.12 (s, 6H), 1.68 (m, J = 7.5 Hz, 3H), 1.14 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 18H).

3-(2-(Dimethylamino)ethyl)-1-(triisopropylsilyl)-1H-indol-4-yl Propionate (ES09)

To a solution of N-TIPS-Psilocin 7 (180 mg, 0.5 mmol) in dry N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF, 4 mL) under argon were added potassium carbonate (69 mg, 0.5 mmol) and potassium iodide (82.8 mg, 0.5 mmol). The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 10 min, and then chloromethyl propanoate (61.2 mg, 500 mmol) was added. The resulting mixture was stirred at room temperature for 2 h. The reaction mixture was quenched by the addition of water. The mixture was then extracted with DCM (3 × 10 mL), and the organic layers were combined, washed with brine, dried over anhydrous MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated. The crude residue was purified by flash column chromatography on silica gel (MeOH/DCM 0:100 to 10:90) to afford product ES09 as a pale-yellow oil (140.4 mg, 68%). HRMS-HESI: calcd for C24H41N2O2Si [M + H]+: 417.2914; found 417.2932. 1H NMR (400 MHz, MeOD) δ 7.43 (dd, J = 8.4, 0.8 Hz, 1H), 7.22 (s, 1H), 7.13 (t, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 6.81 (dd, J = 7.7, 0.7 Hz, 1H), 3.10–2.92 (m, 4H), 2.78 (q, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 2.59 (s, 6H), 1.76 (h, J = 7.5 Hz, 3H), 1.30 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 3H), 1.18 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 18H).

3-(2-(Dimethylamino)ethyl)-1H-indol-4-yl Methyl Isophthalate (ES10)

To a suspension of psilocin 1 (102 mg, 0.50 mmol) in dry DCM (1.5 mL) under an argon atmosphere was added triethylamine (70 μL, 0.50 mmol), followed by isophthaloyl dichloride (51 mg, 0.25 mmol) dissolved in dry DCM (0.5 mL). The reaction mixture was allowed to stir at room temperature for 18 h. The crude reaction mixture was concentrated and directly purified by flash column chromatography on silica gel (MeOH/DCM 10:90 to 20:80) to afford a mixture of products. This mixture was further purified by second flash column chromatography on silica gel (MeOH/DCM 10:90) to yield ES10 (7 mg, 8%) as a colorless oil. HRMS-HESI: calcd for C21H23N2O4 [M + H]+: 367.1652; found 367.1650. 1H NMR (400 MHz, MeOD) δ 8.91 (td, J = 1.8, 0.6 Hz, 1H), 8.54 (ddd, J = 7.8, 1.8, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 8.40 (dt, J = 7.9, 1.4 Hz, 1H), 7.80 (td, J = 7.8, 0.6 Hz, 1H), 7.38 (dd, J = 8.2, 0.8 Hz, 1H), 7.27 (d, J = 0.8 Hz, 1H), 7.21 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 6.91 (dd, J = 7.7, 0.8 Hz, 1H), 4.00 (s, 3H), 3.29 (dd, J = 8.6, 6.8 Hz, 2H), 3.12–3.06 (m, 2H), 2.65 (s, 6H).

Benzyl 4-(((Benzyloxy)carbonyl)oxy)-3-(2-(dimethylamino)ethyl)-1H-indole-1-carboxylate (C01)

To a suspension of psilocin 1 (98 mg, 0.48 mmol) in dry DCM (2.0 mL) under an argon atmosphere was added triethylamine (0.12 mL, 0.87 mmol), followed by benzyl chloroformate (75 μL, 0.52 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 4 h until the starting material was no longer visualized on TLC (20% MeOH/DCM). Following dilution with DCM (10 mL) and methanol (1 mL), the reaction mixture was washed with brine, dried over anhydrous MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated to afford the crude product as an amber oil. Purification by flash column chromatography on silica gel (MeOH/DCM 0:100 to 10:90) yielded C01 (58 mg, 25%) as a white solid. HRMS-HESI: calcd for C28H29N2O5 [M + H]+: 473.2071; found 473.2059. 1H NMR (400 MHz, MeOD) δ 7.57–7.35 (m, 10H), 7.31 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.26 (s, 1H), 7.11 (tt, J = 8.1, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 6.96 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 5.26–5.19 (m, 2H), 4.45 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 2H), 3.53–3.43 (m, 2H), 3.26–3.15 (m, 2H), 2.95–2.90 (m, 6H).

Benzyl (3-(2-(Dimethylamino)ethyl)-1H-indol-4-yl) Carbonate (C02)

To a suspension of psilocin 1 (100 mg, 0.49 mmol) and potassium carbonate (68 mg, 0.49 mmol) in dry DMF (1.2 mL) under an argon atmosphere was added benzyl chloroformate (70 μL, 0.49 mmol). The reaction mixture was allowed to stir at room temperature for 4 h until completion, as determined by TLC (20% MeOH/DCM). Following dilution with water (10 mL), the reaction mixture was extracted with DCM (3 × 10 mL). The combined organic extracts were washed with brine (10 mL), dried over anhydrous MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated. Purification by flash column chromatography on silica gel (MeOH/DCM 0:100 to 10:90) yielded C02 (38 mg, 23%) as a light-yellow oil. HRMS-HESI: calcd for C20H23N2O3 [M + H]+: 339.1703; found 339.1701. 1H NMR (400 MHz, MeOD) δ 7.63 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 7.55–7.49 (m, 2H), 7.46–7.36 (m, 3H), 7.33 (s, 1H), 7.09 (t, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 6.60 (dd, J = 7.9, 0.8 Hz, 1H), 5.44 (s, 2H), 3.02 (td, J = 7.3, 1.0 Hz, 2H), 2.78 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 2.38 (s, 6H).

Cyclopropylmethyl (3-(2-(Dimethylamino)ethyl)-1H-indol-4-yl) Carbonate (C03)

To a solution of C05 (165 mg, 360 μmol) in dry THF (1.80 mL) was added tetrabutylammonium fluoride (TBAF) solution (1 M in THF, 540 μL, 540 μmol) dropwise at 0 °C. After 1 h, water (2 mL) was added, and the aqueous layer was separated and extracted with DCM (3 × 15 mL). The combined organic layers were washed with brine, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated. The crude product was purified by flash column chromatography using silica gel (MeOH/DCM 8:92) to afford pure product C03 as a colorless oil (32 mg, 29%). HRMS-HESI: calcd for C17H23N2O3 [M + H]+: 303.1703; found 303.1702. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.35 (s, 1H), 7.22 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.13 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 6.97 (dt, J = 2.1, 1.0 Hz, 1H), 6.91 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 4.12 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 3.03–2.93 (m, 2H), 2.72–2.65 (m, 2H), 2.38 (s, 6H), 1.35–1.21 (m, 1H), 0.71–0.59 (m, 2H), 0.43–0.34 (m, 2H).

3-(2-(Dimethylamino)ethyl)-1H-indol-4-yl (2,2,2-trichloroethyl) Carbonate (C04)

To a mixture of psilocin 1 (100 mg, 0.49 mmol) in anhydrous DCM (2 mL) was added triethylamine (137 μL, 0.98 mmol), followed by 2,2,2-trichloroethyl chloroformate (135 μL, 0.98 mmol). The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 4 h until the reaction was complete, as determined by TLC (20% MeOH/DCM). After dilution with DCM (10 mL), the reaction mixture was washed with brine (15 mL), dried over anhydrous MgSO4, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude product was purified by flash column chromatography on silica gel (MeOH/DCM 2.5:97.5 to 10:90) to yield C04 (10 mg, 5.5%) as a colorless oil. HRMS-HESI: calcd for C15H18Cl3N2O3 [M + H]+: 379.0378; found 379.0378. 1H NMR (400 MHz, MeOD) δ 7.69 (dd, J = 8.3, 0.8 Hz, 1H), 7.36 (d, J = 1.0 Hz, 1H), 7.14 (t, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 6.65 (dd, J = 7.9, 0.8 Hz, 1H), 5.15 (s, 2H), 3.08–3.01 (m, 2H), 2.80 (dd, J = 7.5, 6.7 Hz, 2H), 2.39 (s, 6H).

Cyclopropylmethyl (3-(2-(Dimethylamino)ethyl)-1-(triisopropylsilyl)-1H-indol-4-yl) Carbonate (C05)

A solution of 7 (250 mg, 693 μmol) and 4-nitrophenyl chloroformate (154 mg, 763 μmol) in DCM (3.47 mL) was cooled to 0 °C, and to it was added N,N-diisopropylethylamine (242 μL, 1.39 mmol) dropwise. The reaction mixture was warmed up to RT and stirred for 2 h. After 2 h, TLC (MeOH/DCM 1:9) showed almost complete conversion to the desired intermediate, 8. To the reaction mixture were added cyclopropanemethanol (168 μL, 2.08 mmol) and N,N-diisopropylethylamine (362 μL, 2.08 mmol) with vigorous stirring at RT. After 2 h, volatiles were removed in vacuo, and the crude mixture was purified by flash column chromatography on silica gel (MeOH/DCM 10:90) to afford the semipure product that contained p-nitrophenol. This material was dissolved in DCM (10 mL) and washed with saturated aqueous NaHCO3 (6 × 20 mL) to remove the residual p-nitrophenol. C05 was obtained as a light-yellow oil (185 mg, 58%). HRMS-HESI: calcd for C26H43N2O3Si [M + H]+: 459.3037; found 459.3031. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.34 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 7.09 (t, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.01 (s, 1H), 6.92 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 4.12 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 3.02–2.94 (m, 2H), 2.66 (t, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 2.38 (s, 6H), 1.66 (h, J = 7.5 Hz, 3H), 1.31–1.22 (m, 1H), 1.13 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 18H), 0.69–0.58 (m, 2H), 0.43–0.34 (m, 2H).

S-Benzyl O-(3-(2-(Dimethylamino)ethyl)-1H-indol-4-yl) Carbonothioate (T01)