Abstract

Background:

An adequate absolute lymphocyte count (ALC) is an essential first step in autologous chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell manufacturing. For patients with acutemyelogenous leukemia (AML), the intensity of chemotherapy received may affect adequate ALC recovery required for CAR T-cell production. We sought to analyze ALC following each course of upfront therapy as one metric for CAR T-cell manufacturing feasibility in children and young adults with AML.

Procedure:

ALC data were collected from an observational study of patients with newly diagnosed AML between the ages of 1 month and 21 years who received treatment between the years of 2006 and 2018 at one of three hospitals in the Leukemia Electronic Abstraction of Records Network (LEARN) consortium.

Results:

Among 193 patients with sufficient ALC data for analysis, the median ALC following induction 1 was 1715 cells/μl (interquartile range: 1166–2388), with successive decreases in ALC with each subsequent course. Similarly, the proportion of patients achieving an ALC >400 cells/μl decreased following each course, ranging from 98.4% (190/193) after course 1 to 66.7% (22/33) for patients who received a fifth course of therapy.

Conclusions:

There is a successive decline of ALC recovery with subsequent courses of chemotherapy. Despite this decline, ALCvalues are likely sufficient to consider apheresis prior to the initiation of each course of upfront therapy for the majority of newly diagnosed pediatric AML patients, thereby providing a window of opportunity for T-cell collection for those patients identified at high risk of relapse or with refractory disease.

Keywords: absolute lymphocyte count, acute myelogenous leukemia, chimeric antigen receptor therapy

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Based on the success of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells in acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL),1,2 the development of CAR T cells for acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) represents a natural extension. Although several phase I CAR T-cell trials targeting various AML antigens are underway,3 effective lymphocyte collection and CAR T-cell manufacturing have emerged as significant challenges.4

The feasibility of autologous CAR T-cell therapy is highly contingent on the sufficient collection of functional lymphocytes for ex vivo expansion and transduction.5 Prior experience with apheresis for CD19 CAR T-cell manufacturing demonstrated that low absolute lymphocyte counts (ALC) <400–500 cells/μl, low CD3 counts (<150 cells/μl), and receipt of specific prior chemotherapies (e.g., clofarabine) may compromise CAR T-cell manufacturing.6–8 As AML therapy is particularly intensive, the proliferative capacity of T cells in patients with AML may be diminished—particularly after multiple cycles of therapy,9,10 and the optimal time point to consider apheresis in patients with AML proceeding to CAR T-cell therapy is unknown. As little is known about ALC recovery in the current era of AML therapy, we sought to describe ALC recovery as one parameter informative to timing of lymphocyte collection for CAR T-cell production.

2 |. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 |. Study design

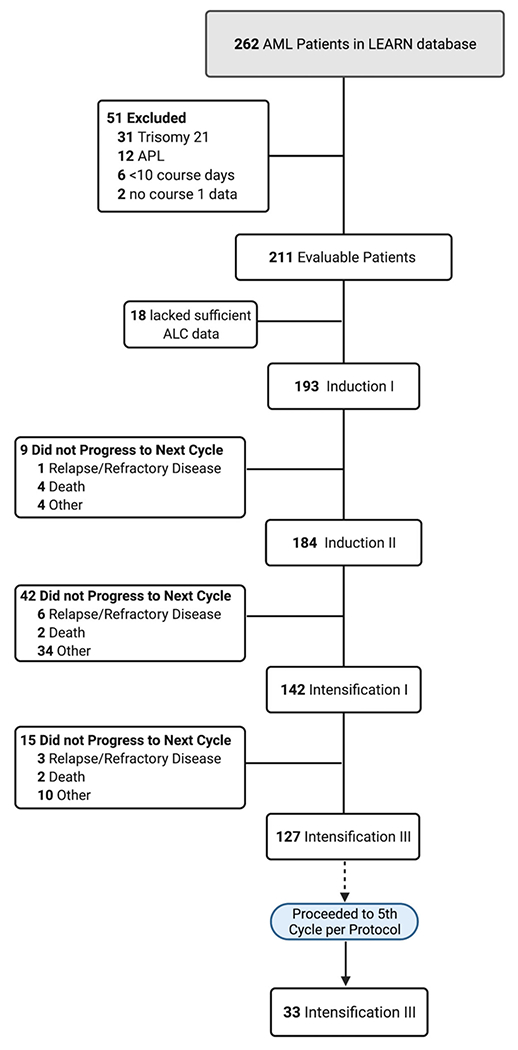

This was an observational study of patients, ages 1 month to 21 years, receiving chemotherapy for newly diagnosed AML from 2006 through mid-2018. Patients were treated at one of three hospitals (Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia [CHOP], Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta [CHOA], and Texas Children’s Hospital [TCH]) in the Leukemia Electronic Abstraction of Records Network (LEARN) consortium.11,12 Institutional Review Board approval was obtained at all sites. Patients with trisomy 21, acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL), with less than 10 course days, or with no data for course 1 were excluded (Figure 1). Patients contributed data for up to five courses of upfront chemotherapy or if they met a specific censoring criterion (refractory disease, relapse, death, pursuit of alternative treatment, transfer of care outside of the LEARN network, or undergoing consolidative hematopoietic stem cell transplant [HSCT]). A subset of patients with relapsed/refractory disease was analyzed for 45 days from the date of relapse or determination of refractory disease.

FIGURE 1.

Cohort diagram

2.2 |. Outcomes of interest

The primary outcome was “end-of-course ALC” defined by the ALC at day 1 of the subsequent chemotherapy course (or, if unavailable, ALC on the last day of the current course)—selected as a potential window of opportunity between treatment cycles for scheduling apheresis. Patients without either value were censored and excluded from analysis of the given course (Figure 1). In situations when white blood cells were too low to generate a differential or provide an ALC count, ALC value was defaulted to “0.” The secondary outcome was end-of-course ALC dichotomized at <400 and ≥400 cells/μl following each treatment course. This threshold was chosen based on prior data from B-ALL CAR T-cell production showing compromised manufacturing ability below 400 cells/μl.8

2.3 |. Statistical analysis

Baseline patient characteristics were summarized for each treatment course using frequencies and proportions for categorical variables, and median and interquartile ranges (IQRs) for continuous variables. End-of-course ALC, median, and IQR were summarized for each treatment course, for the overall cohort, and by various demographical groups. For dichotomized ALC, frequencies and proportions were summarized. To test if the observed trend in the end-of-course median ALC values across treatment courses was significant, a mixed effects model was constructed on log-transformed ALC values due to skewing of raw ALC values. This model included course number and patient characteristics as fixed effects, and random intercept and random slope for each patient. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.3, and a two-sided p-value <.05 was considered statistically significant.

3 |. RESULTS

3.1 |. Patient and treatment characteristics

A total of 193 patients had available ALC data following Induction I for analysis (Figure 1). For patients completing Induction 1, the median age in the study population was 9.7 years and the majority of patients were female (54.0%, n = 104) and White (60%, n = 116). Of patients with an AML risk group documented in the EMR, 29% (n = 56) were designated as high risk. Most patients were treated on-study or per Children’s Oncology Group trials AAML1031 (57%, n = 110) or AAML0531 (38%, n = 74) (Table S1).AAML1031 was designed to administer four courses of chemotherapy that include: Induction 1 (cytarabine, daunorubicin, and etoposide [ADE]), Induction 2 (ADE vs. mitoxantrone/cytarabine [MA]), Intensification 1 (cytarabine and etoposide [AE]), and Intensification 2 (MA vs. high-dose cytarabine) with or without additional agents (Table S2). Patients treated on-study or per AAML 0531 had the potential to receive a fifth course of high-dose cytarabine plus L-asparaginase. The median length of treatment courses ranged from 38 to 44 days.

3.2 |. Lymphocyte recovery following treatment

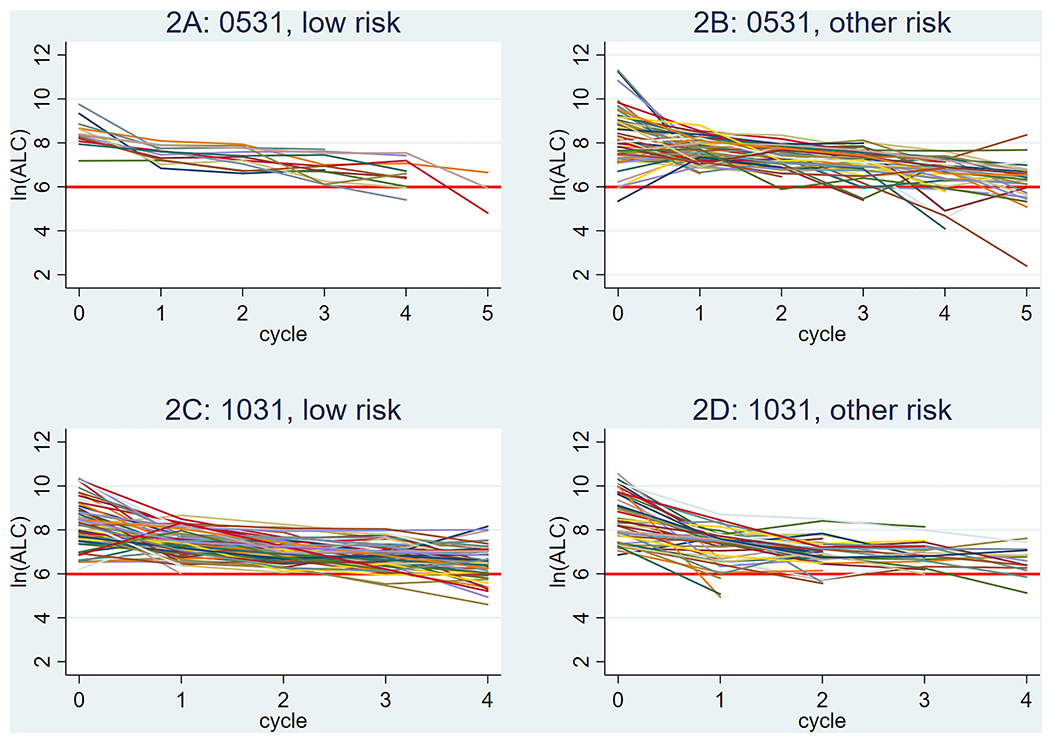

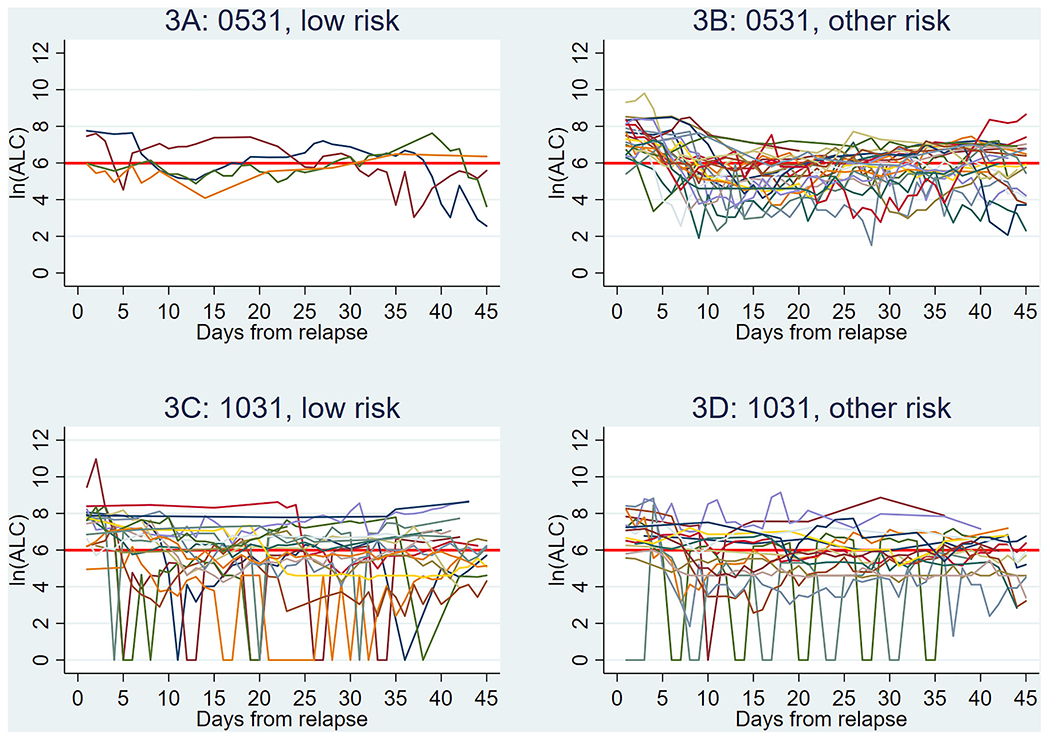

The median end-of-course ALC following Induction 1 was 1715 cells/μl (IQR: 1166–2388) with successive decreases in ALC values with each subsequent course of therapy (Table 1, Figure 2). This decreasing trend remained significant after adjusting for patient demographic and treatment characteristics (p < .001, Table S4). Despite a successive decline during treatment, the majority of patients achieved an ALC recovery >400 cells/μl at conclusion of each course of chemotherapy (Table S3). Following the first course of therapy, 98.4% (190/193) achieved an adequate ALC recovery of >400 cells/μl for potential T-cell collection. This decreased to 81.1% (103/127) for patients who completed four courses of upfront chemotherapy, and 66.7% (22/33) for patients who underwent a fifth course of therapy per protocol design. For the cohort of relapsed/refractory patients (n = 72), the median ALC at 45 days post relapse was 435 cells/μl (IQR: 164–892) with 51.4% having an ALC ≥400 cells/μl (Table 1, Figure 3).

TABLE 1.

Median ALC values (cells/μl) at completion of chemotherapy cycles

| Induction I (n = 193) | Induction 2 (n = 184) | Intensification 1 (n = 142) | Intensification 2 (n = 127) | Intensification 3 (n = 33) | Relapsed/refractory a (n = 72) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall cohort | 1715 (1166, 2388) | 1329 (844, 1961) | 1039 (717, 1587) | 736 (459, 1178) | 609 (364, 774) | 436 (165, 892) |

|

| ||||||

| Institution | ||||||

| CHOA | 1519 (1084, 2280) | 1047 (720, 1463) | 926 (520, 1392) | 691 (361, 1132) | 537 (293, 709) | 518 (270, 1025) |

| CHOP | 1937 (1332, 2420) | 1535 (920, 2000) | 1102 (780, 1450) | 726 (518, 1188) | 672 (364, 900) | 660 (269, 1075) |

| TCH | 1791 (1210, 2400) | 1548 (1154, 2395) | 1198 (901, 1992) | 904 (621, 1281) | 546 (334, 786) | 265 (51, 780) |

|

| ||||||

| Age group | ||||||

| 0–12 months | 3371 (2400, 4664) | 2367 (1478, 3018) | 2070 (1424, 2520) | 677 (184, 1517) | 460 (343, 880) | 1131 (576, 2340) |

| 1–5 years | 2147 (1469, 3380) | 1840 (1330, 2531) | 1437 (1080, 1992) | 959 (518, 1238) | 694 (450, 830) | 680 (230, 1217) |

| 6–11 years | 1925 (1336, 2250) | 1235 (798, 1651) | 990 (627, 1386) | 825 (527, 1245) | 672 (162, 799) | 275 (100, 1203) |

| 12–18 years | 1213 (854, 1737) | 891 (670, 1296) | 886 (638, 1102) | 661 (389, 950) | 493 (241, 663) | 370 (150, 595) |

| 19–21 years | 2119 (764, 2916) | 861 (855, 868) | 667 (492, 895) | 650 (568, 733) | 651 (–, –) | 170 (–, –) |

|

| ||||||

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 1734 (1166, 2268) | 1342 (920, 1944) | 10,233 (710, 1702) | 705 (407, 1171) | 540 (308, 749) | 611 (175, 1141) |

| Female | 1693 (1180, 2470) | 1261 (798, 1981) | 1078 (755, 1503) | 764 (518, 1206) | 609 (460, 830) | 370 (155, 685) |

|

| ||||||

| Race | ||||||

| White | 1754 (1272, 2337) | 1339 (896, 1961) | 1032 (792, 1460) | 795 (518, 1168) | 531 (280, 799) | 400 (125, 980) |

| Black | 1655 (982, 2393) | 1254 (730, 1840) | 1094 (644, 1702) | 672 (406, 1171) | 696 (460, 774) | 680 (269, 900) |

| Other race or unknown | 1655 (982, 2393) | 1329 (860, 2343) | 1088 (644, 1659) | 802 (471, 1569) | 609 (230, 694) | 170 (90, 370) |

|

| ||||||

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| Hispanicor Latino | 1866 (1315, 2369) | 1614 (1269, 1965) | 1180 (910, 1536) | 931 (459, 1292) | 609 (280, 799) | 461 (170, 1012) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 1697 (1147, 2420) | 1261 (818, 1720) | 1011 (674, 1587) | 732 (427, 1156) | 683 (388, 860) | 388 (47, 956) |

| Unknown | 1394 (1022, 2367) | 983 (660, 1800) | 1125 (659, 1856) | 731 (568, 1890) | 372 (297, 515) | 409 (384, 660) |

|

| ||||||

| Risk group | ||||||

| Not reported | 1777 (1320, 2964) | 1547 (1144, 2352) | 1248 (699, 2070) | 592 (364, 1079) | 609 (306, 860) | 787 (165, 948) |

| Low risk | 1563 (1119, 2392) | 1288 (823, 1840) | 963 (683, 1450) | 677 (434, 1171) | 380 (123, 774) | 510 (165, 1177) |

| Intermediate | 1926 (1256, 2344) | 1539 (1167, 2440) | 1451 (1003, 1872) | 913 (580, 1245) | 596 (450, 799) | 246 (54, 524) |

| High risk | 1672 (1149, 2193) | 1099 (664, 1554) | 959 (733, 1408) | 940 (595, 1173) | 724 (–, –) | 390 (243, 900) |

|

| ||||||

| Chemo protocol | ||||||

| AAML 1031 or AAML 1031-like | 1655 (1080, 2350) | 1320 (798, 1668) | 940 (683, 1424) | 677 (459, 1141) | – | – |

| AAML 0531 or AAML 0531-like | 1866 (1320, 2690) | 1535 (1088, 2340) | 1248 (879, 1861) | 865 (468, 1217) | 620 (343, 786) | – |

| AAML03P1 | 1778 (1394, 2162) | 2256 (1296, 3216) | 2667 (–, –) | 483 (–, –) | 364 (–, –) | – |

| Other | 847 (472, 2280) | 354 (148, 720) | 515 (138, 1175) | 1640 (–, –) | – | – |

Note: All ALC values are shown as median (IQR), as cells/μl unless otherwise indicated.

Abbreviations: ALC, absolute lymphocyte count; CHOA, Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta; CHOP, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia; TCH, Texas Children’s Hospital.

ALC values at day 45 post relapse or determination of refractory disease.

FIGURE 2.

Individual absolute lymphocyte count (ALC) (natural log [ln] scale) over treatment course by protocol and risk stratification. Data are shown starting at pretreatment baseline (x = 0), with each successive value indicative of the individual value following the completion of a chemotherapy cycle (1 = Induction I; 2 = Induction 2; 3 = Intensification 1; 4 = Intensification 2; 5 = Intensification 3). Red line corresponds to an ALC value of 400. (A) ALC values for patients with low-risk cytogenetics enrolled on AAML0531 (n = 13, 12, 13, 13, 11, and 3, at baseline and subsequent courses, respectively). (B) ALC values for patients with other cytogenetics (non-low risk) enrolled on AAML0531 (n = 66, 62, 62, 47, 41, and 29, at baseline and subsequent courses, respectively). (C) ALC values for patients with low-risk cytogenetics enrolled on AAML1031 (n = 65, 66, 64, 55, and 59, at baseline and subsequent courses, respectively). (D) ALC values for patients with other cytogenetics (non-low risk) enrolled on AAML1031 (n = 45, 44, 37, 22, and 14, at baseline and subsequent courses, respectively). The y-axis legend (in natural log): ln (ALC) of 2 = ALC of 7, ln (ALC) of 4 = ALC of 55, ln (ALC) of 6 = ALC of 403, ln (ALC) of 8 = ALC of 2981, ln (ALC) of 10 = ALC of 22,026, ln (ALC) of 12 = ALC of 162,755

FIGURE 3.

Individual absolute lymphocyte count (ALC) (natural log [ln] scale) for relapsed patients (n = 72 patients overall). Data are shown starting at relapse (x = 0), with each successive value indicative of the individual values following time post relapse (in days). Red line corresponds to an ALC value of 400. Not all patients had a daily value, and the number of samples per each time point ranged. (A) ALC values for patients with low-risk cytogenetics enrolled on AAML0531 (n = 1–4, per each time point). (B) ALC values for patients with other cytogenetics (non-low risk) enrolled on AAML0531 (n = 11–22, per each time point). (C) ALC values for patients with low-risk cytogenetics enrolled on AAML1031 (n = 8–17, per each time point). (D) ALC values for patients with other cytogenetics (non-low risk) enrolled on AAML1031 (n = 8–16, per each time point). The y-axis legend (in natural log): ln (ALC) of 2 = ALC of 7, ln (ALC) of 4 = ALC of 55, ln (ALC) of 6 = ALC of 403, ln (ALC) of 8 = ALC of 2981, ln (ALC) of 10 = ALC of 22,026, ln (ALC) of 12 = ALC of 162,755

4 |. DISCUSSION

In the largest contemporary study of ALC in children, adolescents, and young adults with newly diagnosed AML, our real world data show a clinically relevant, successive decline in ALC recovery with subsequent courses of chemotherapy and provides a relative benchmark for considerations of when an early apheresis could be performed for potential future use, particularly in those at high risk for relapse. Importantly, while the majority were able to achieve an ALC recovery above the preferred minimal threshold of ≥400 cells/μl needed to produce a viable CAR T-cell product,8 this number steadily declined with additional therapy, at relapse, and in patients refractory to upfront therapy. These results emphasize that apheresis prior to proceeding with a fourth cycle of chemotherapy (Intensification III) may represent a window of opportunity for AML patients, particularly for patients receiving five or more courses of therapy and prior to disease relapse in high-risk patients.

While our dataset does not facilitate assessment of qualitative T-cell defects resulting from cumulative exposure to AML-directed therapy, chemotherapy-related depletion of early lineage cells, in particular naive T cells, has been shown to cause a decline in ex vivo CAR T-cell stimulation response, expansion, and persistence.9,13 For AML specifically, naïive T cells begin to decline post course 4 of therapy compared to prechemotherapy levels with a significant decline of in vitro expansion following three courses of treatment.9 Even with successful manufacturing, exposure to prior lines of chemotherapy may result in persistent T-cell metabolic dysfunction in surviving cells affecting the quality of CAR T products and their long-term proliferative capacity.14 Additionally, the study was also limited in its ability to evaluate T-cell counts or perform more extensive profiling at the time of diagnosis or throughout the course of treatment, primarily as these data are not routinely collected. Future efforts in serial collection of T-cell immunophenotyping could further aid in defining optimal timing to pursue apheresis given the importance of the composition of infusion product,15 particularly as peripheral T cells in AML at diagnosis have abnormal phenotype and genotype with aberrant T-cell activation patterns that may normalize at the time of remission and affect CAR T-cell functionality, depending on the timing of cell collection.16

While the observed decrease in ALC recovery with each subsequent course of treatment and the potential for persistent T-cell metabolic dysfunction with progressive chemotherapy exposure support earlier apheresis, logistical and financial challenges must also be addressed for early T-cell collection for a collect and freeze model.17 Data from commercial CAR T-cell production for B-ALL have shown that leukapheresis products can be cryopreserved for long-term storage with no negative effects on post-thaw cell viability up to 30 months prior to CAR manufacturing and possibly longer.18 However, for patients with high-risk AML where the standard approach is to undergo consolidative HSCT in first remission (which occurred in 25.9% of our study population), use of T cells collected pre-transplant could not be used to generate an autologous CAR product for a potential post-HSCT relapse. Additional challenges surround the financing of product storage and use of previous collected leukapheresis products for the manufacturing of commercial and/or experimental CAR T cells.

In conclusion, the failure to manufacture a viable CAR T-cell product is a major barrier to the overall success of CAR T-cell trials, thus consideration of early leukapheresis for ongoing and future AML CAR T-cell trials is warranted. Future efforts focused on assessing and identifying factors impacting lymphocyte functionality alongside study of the impact of novel/targeted agents (e.g., hypomethylating agents or BCL2 inhibitors) on ALC will provide further guidance for optimal timing of T-cell collection when planning for AML adoptive cell therapy.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program, National Cancer Institute and NIH Clinical Center, National Institutes of Health (ZIA BC 011823), the Alex’s Lemonade Stand Foundation, and the Hematologic Malignancies Research Fund at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views of policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Funding information

National Cancer Institute; NIH Clinical Center; National Institutes of Health, Grant/Award [ISP-CHK ALL]Number: ZIA BC011823; Alex’s Lemonade Stand Foundation; Hematologic Malignancies Research Fund; Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia; Alex’s Lemonade Stand Foundation for Childhood Cancer; Center for Childhood Cancer Research, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia

Abbreviations:

- ALC

absolute lymphocyte count

- ALL

acute lymphoblastic leukemia

- AML

acute myelogenous leukemia

- CAR

chimeric antigen receptor

- HSCT

hematopoietic stem cell transplant

- IQR

interquartile ranges

- LEARN

Leukemia Electronic Abstraction of Records Network

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information can be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of this article.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Shah NN, Lee DW, Yates B, et al. Long-term follow-up of CD19-CAR T-cell therapy in children and young adults with B-ALL. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39:1650. 10.1200/jco.20.02262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maude SL, Laetsch TW, Buechner J, et al. Tisagenlecleucel in children and young adults with B-cell lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(5):439–448. 10.1056/NEJMoa1709866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mardiana S, Gill S. CAR T cells for acute myeloid leukemia: state of the art and future directions. Front Oncol. 2020;10:697. 10.3389/fonc.2020.00697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tambaro FP, Singh H, Jones E, et al. Autologous CD33-CAR-T cells for treatment of relapsed/refractory acute myelogenous leukemia. Leukemia. 2021;35(11):3282–3286. 10.1038/s41375-021-01232-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shah NN, Fry TJ. Mechanisms of resistance to CAR T cell therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2019;16(6):372–385. 10.1038/s41571-019-0184-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hutt D, Bielorai B, Baturov B, et al. Feasibility of leukapheresis for CAR T-cell production in heavily pre-treated pediatric patients. Transfus Apher Sci. 2020;59(4):102769. 10.1016/j.transci.2020.102769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Korell F, Laier S, Sauer S, et al. Current challenges in providing good leukapheresis products for manufacturing of CAR-T cells for patients with relapsed/refractory NHL or ALL. Cells. 2020;9(5):1225. 10.3390/cells9051225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hayden PJ, Roddie C, Bader P, et al. Management of adults and children receiving CAR T-cell therapy: 2021 best practice recommendations of the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) and the Joint Accreditation Committee of ISCT and EBMT (JACIE) and the European Haematology Association (EHA). Ann Oncol. 2022;33(3):259–275. 10.1016/j.annonc.202112.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Das RK, Vernau L, Grupp SA, Barrett DM. Naive T-cell deficits at diagnosis and after chemotherapy impair cell therapy potential in pediatric cancers. Cancer Discov. 2019;9(4):492–499. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-18-1314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Das RK, O’Connor RS, Grupp SA, Barrett DM. Lingering effects of chemotherapy on mature T cells impair proliferation. Blood Adv. 2020;4(19):4653–4664. 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020001797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller TP, Getz KD, Demissei B, et al. Rates of laboratory adverse events by chemotherapy course for pediatric acute leukemia patients within the Leukemia Electronic Abstraction of Records Network (LEARN). Blood. 2019;134(Supplement_1):333. 10.1182/blood-2019-13065631345924 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller TP, Getz KD, Li Y, et al. Rates of laboratory adverse events by course in paediatric leukaemia ascertained with automated electronic health record extraction: a retrospective cohort study from the Children’s Oncology Group. Lancet Haematol. 2022;9(9):e678–e688. 10.1016/S2352-3026(22)00168-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sabatino M, Hu J, Sommariva M, et al. Generation of clinical-grade CD19-specific CAR-modified CD8+ memory stem cells for the treatment of human B-cell malignancies. Blood. 2016;128(4):519–528. 10.1182/blood-2015-11-683847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Das RK, O’Connor RS, Grupp SA, Barrett DM. Lingering effects of chemotherapy on mature T cells impair proliferation. Blood Adv. 2020;4(19):4653–4664. 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020001797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bai Z, Woodhouse S, Zhao Z, et al. Single-cell antigen-specific landscape of CAR T infusion product identifies determinants of CD19-positive relapse in patients with ALL. Sci Adv. 2022;8(23):eabj2820. 10.1126/sciadv.abj2820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Le Dieu R, Taussig DC, Ramsay AG, et al. Peripheral blood T cells in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients at diagnosis have abnormal phenotype and genotype and form defective immune synapses with AML blasts. Blood. 2009;114(18):3909–3916. 10.1182/blood-2009-02-206946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Palen K, Zurko J, Johnson BD, Hari P, Shah NN. Manufacturing chimeric antigen receptor T cells from cryopreserved peripheral blood cells: time for a collect-and-freeze model? Cytotherapy. 2021;23(11):985–990. 10.1016/j.jcyt.2021.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qayed M, McGuirk JP, Myers GD, et al. Leukapheresis guidance and best practices for optimal chimeric antigen receptor T-cell manufacturing. Cytotherapy. 2022;24(9):869–878. 10.1016/j.jcyt.2022.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.