Abstract

This narrative review provides an overview of the utilization of endoscopic ultrasound-guided gallbladder drainage (EUS-GBD) as a salvage approach in cases of unsuccessful conventional management. EUS-GBD is a minimally invasive and effective technique for drainage in patients with acute cholecystitis with high risk of surgery. The procedure has demonstrated impressive technical and clinical success rates with low rates of adverse events, making it a safe and effective option for appropriate candidates. Furthermore, EUS-GBD can also serve as a rescue option for patients who have failed endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography or EUS biliary drainage for relief of jaundice in malignant biliary stricture. However, patient selection is critical for the success of EUS-GBD, and proper patient selection and risk assessment are important to ensure the safety and efficacy of the procedure. As the field continues to evolve and mature, ongoing research will further refine our understanding of the benefits and limitations of EUS-GBD, ultimately leading to improved outcomes for patients.

Keywords: Endoscopic ultrasound-guided gallbladder drainage, Gallbladder drainage, Acute cholecystitis, Malignant obstruction, Interventional endoscopic ultrasound, Lumen-apposing metal stents

Core Tip: This review article explores the use of a minimally invasive procedure called endoscopic ultrasound-guided gallbladder drainage (EUS-GBD) as a salvage technique for cases of unsuccessful biliary drainage (BD) with conventional approach. EUS-GBD has been shown to be effective in relieving biliary obstruction in patients who have failed other treatment options such as endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and EUS BD. The article summarizes the safety and efficacy of EUS-GBD in various studies, and discusses its potential advantages and limitations compared to other drainage options. The authors aim to offer a comprehensive overview of the potential role of EUS-GBD for various indications as a rescue therapy for malignant biliary obstruction when conventional treatment options fail, and to provide insights into the challenges and limitations associated with the procedure.

INTRODUCTION

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) has significantly evolved during the past decade, currently offering entire breadth of therapeutic procedures, including pancreatic fluid collections and biliary drainage (BD), gastro-entero-anastomoses creation, and vascular interventions. Also, a gallbladder drainage (EUS-GBD) is nowadays a well-established alternative to percutaneous transhepatic GBD (PT-GBD) in the management of acute cholecystitis (AC) in patients unfit for surgery[1]. This procedure is minimally invasive and can provide quick relief to patients who have failed to respond to other conventional treatment options. Recently, the use EUS-GBD has expanded to include its use as a rescue technique after failed endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) or EUS-BD for palliation of malignant jaundice.

Palliation of malignant biliary obstruction has traditionally been achieved through ERCP with stent placement. However, in cases where ERCP fails or is not feasible, alternative techniques such as EUS-guided biliary EUS-BD have emerged as effective options. By expanding the armamentarium for BD, EUS-BD offers a valuable alternatives for palliation in patients with failed ERCP or those who are not suitable candidates for conventional techniques[2-5].

The aim of this review is to offer a comprehensive overview of the potential role of EUS-GBD for different indications focusing on rescue approach for malignant biliary obstruction when conventional treatment options, such as ERCP and EUS-BD, fail. EUS-GBD can serve as an alternative route for decompression of the biliary system in such cases, offering a viable solution to relieve malignant distal bile duct obstruction instead of to perform PTBD.

TECHNICAL ASPECTS

EUS-GBD is a minimally invasive procedure that can be performed on an outpatient basis, typically under conscious sedation or deep sedation, with a lower risk of complications than surgical or percutaneous procedures. EUS-GBD is performed via a transmural approach accessing the gallbladder lumen directly from the gastric antrum (cholecystogastrostomy) or duodenal bulb (cholecystoduodenostomy) and placing a stent to establish a bile drainage route. The access selection depends on the proximity to the gallbladder, presence of duodenal obstruction, and discretion of endoscopist. Both accesses are safe and effective, but differ technically in terms of anatomical region of the gallbladder which can be targeted. From the duodenal bulb rather the neck of gallbladder will be punctured, whereas from the gastric antrum body, the access will be better for the gallbladder body. In terms of advantages, trans-duodenal route might be related with lower risk of stent migration and lower risk of food passage to the gallbladder, in the long-term perspective. Besides, retroperitoneal location of the duodenum provides more stable position for procedure performance[6]. On the other hand, trans gastric access gives more space during the stent deployment, also closure of the fistula after drainage completion appears to be easier[6].

In the past, different types of stents were used for EUS-GBD, including plastic double pigtails and self-expandable metal stents (SEMS). However, due to high risk of migration, collateral wall injury as well leaking, these seems to be no longer commonly chosen. In contrary, lumen-apposing metal stents (LAMS) became the first choice for EUS-GBD. Their design composed of bilateral anchor flanges allows lumen apposition, hence lower migration rate was observed[7]. Besides, coverage of stent by silicone prevents leaking or tissue ingrowth, thus, LAMS may be used for short and longer GBD purposes[8].

Currently, there are three types of LAMS available including AXIOS (Boston Scientific, Mattick, MA, United States), NAGI (Taewoong, Gimpo, Korea) and SPAXUS (Taewoong, Gimpo, Korea). The general design is similar with differences in flange diameter, length, and lumen diameter (Table 1). LAMS with smaller lumen diameter might be preferred for EUS-GBD. However, larger LAMS can be used for peroral cholecystoscopic interventions[9]. Also, LAMS can be divided to containing electrocautery (EC) option or without, what will determine the way of procedures performance.

Table 1.

Types of currently available lumen-apposing metal stents

|

Stent

|

Flare diameter (mm)

|

Lumen diameter (mm)

|

Length (mm)

|

Electrocautery enhanced tip

|

| AXIOS stent (Boston Scientific Co., Marlborough, MA, United States) | 21, 24, 29 | 6, 8, 10, 15, 20 | 10, 15 | Yes |

| SPAXUS stent (Taewoong Medical Co., Gimpo, Korea) | 23, 25, 31 | 8, 10, 16 | 20 | Yes |

| NAGI stent (Taewoong Medical Co., Gimpo, Korea) | 20 | 10, 12, 14, 16 | 10, 20, 30 | No |

The evolution of accessories specifically designed for EUS-GBD will further reduce the risk of adverse events (AEs) associated with the procedure, with potential improvements in technical and clinical success rates. Accessories like the EC-LAMS deployment system are believed to be beneficial because they decrease the number of accessories exchanged, potentially reducing the frequency of complications[10,11]. When EC-tip is selected, procedure does not require EUS needle (typically 19G-needle), guidewire (0.025 or 0.035-inch), and tract-dilating accessory.

In general, that spares time of the procedure when free-hand insertion technique is used. On the other hand, over-the-wire technique may help in keeping the access when the scope position is challenging and mis-deployment of the stent may occur[8]. Choice of the stent depends mainly on the endoscopist preference, however one study showed advantage of AXIOS and SPAXUS over the NAGI stent for EUS-guided trans-enteric GBD[8]. Despite plastic stents are not used directly for the EUS-GBD, they might be deployed through the lumen of LAMS, potentially preventing complications like stent obstruction, and contralateral wall injury[12].

ACUTE CHOLECYSTITIS

AC is a common inflammatory disorder of the gallbladder, and in some cases, medical therapy may not be effective. The incidence of AC has been increasing worldwide, with estimates ranging from 10% to 20% of the adult population. Traditionally, the treatment for AC involves hospital admission, antibiotics, and either surgical cholecystectomy or PTGBD[13]. However, both approaches carry a significant risk of complications, including bleeding, infection, and organ injury, and can lead to prolonged hospital stays and recovery periods. In addition, patients with severe AC may not be candidates for surgical intervention due to comorbidities or high surgical risk.

High-risk surgical patients can be defined as individuals who have underlying medical conditions, such as cirrhosis, severe heart or lung disease, or other comorbidities, which significantly increase the surgical risk. These patients may not be suitable candidates for conventional surgical interventions due to the elevated likelihood of complications and prolonged recovery periods.

The two widely accepted endoscopic techniques for GBD are the endoscopic transpapillary GBD (ET-GBD) and the transmural EUS-GBD. While ET-GBD has shown success in certain cases, it is important to note that it may not be feasible or effective in all patients, especially those with altered anatomy or difficult papillary access. In comparison, transmural EUS-GBD offers a minimally invasive alternative, allowing direct access to the gallbladder from the gastrointestinal wall under EUS guidance. In the past decade, EUS-GBD has become an increasingly popular alternative to PT-GBD and surgical cholecystectomy in the management of AC who are at high surgical risk[13]. EUS-GBD has been shown to have several advantages over traditional approaches, including higher success rates, lower complication rates, shorter hospital stays and provide a quicker return to daily activities.

EUS-GBD can be considered in patients with AC who are at high surgical risk, such as those with cirrhosis or severe heart or lung disease. In these cases, EUS-GBD can provide a less invasive and less risky alternative to surgical cholecystectomy[14]. EUS-GBD can also be used in patients with chronic cholecystitis who are not candidates for surgery due to underlying medical conditions. In addition, EUS-GBD can be performed in patients with complex biliary anatomy, such as those with a high cystic duct insertion or Mirizzi syndrome, where surgical intervention may be challenging. EUS-GBD can also be performed in patients who have undergone previous biliary surgery and who have strictures or complications related to the surgical procedure[14,15].

In the recent meta-analysis, EUS-GBD procedure was compared with PT-GBD, where the pooled technical success was 89.9% [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.87-0.92] and 87.5% (95%CI: 0.85-0.90), respectively[16]. Clinical success in EUS-GBD group was observed in 97% (95%CI: 0.95-0.98) of patients, and in 94.1% (95%CI: 0.92-0.96) of the patients treated with PT-GBD[16]. Despite that above mentioned results for AC treatment were almost comparable, differed significantly when AEs rate was assessed, ranging 14.6% and nearly 30% for EUS-GBD and PT-GBD, respectively. Among these, abdominal pain, stent dislodgement, bleeding, stent obstruction and recurrent cholecystitis were the most common[16], please refer to Table 2 for comparative studies on EUS-GBD vs PT-GBD.

Table 2.

Studies comparing endoscopic ultrasound-guided gallbladder drainage vs percutaneous transhepatic gallbladder drainage outcomes for acute cholecystitis

|

Ref.

|

Number of patients

|

Procedure

|

Technical success (%)

|

Clinical success (%)

|

Adverse events (%)

|

| Jang et al[28] | 59 | EUS-GBD | 97 | 100 | 7 |

| PTGBD | 97 | 96 | 3 | ||

| Kedia et al[29] | 73 | EUS-GBD | 97.6 | 97.6 | 13.3 |

| PTGBD | 100 | 86.7 | 39.5 | ||

| Teoh et al[30] | 118 | EUS-GBD | 96.6 | 89.8 | 32.2 |

| PTGBD | 100 | 94.9 | 74.6 | ||

| Irani et al[31] | 90 | EUS-GBD | 98 | 96 | 11 |

| PTGBD | 100 | 91 | 32 | ||

| Tyberg et al[32] | 155 | EUS-GBD | 95 | 95 | 21.4 |

| PTGBD | 99 | 86 | 21.2 |

EUS-GBD: Endoscopic ultrasound-guided gallbladder drainage; PTGBD: Percutaneous transhepatic gallbladder drainage.

For patients with minimal life expectancies or high-risk comorbidities, the initial placement of a LAMS by EUS-GBD has allowed for definitive therapy[10]. The need for an additional double-pigtail plastic stent inside the LAMS remains unclear. Additionally, the optimal duration of stenting and whether stents should be removed after resolution of AC are open questions. Studies show that minimal AEs occur even up to three years with both SEMS and LAMS, suggesting that long-term stenting is a viable option. Alternatively, for patients who require long-term treatment, the LAMS can be replaced after approximately one month by a double-pigtail plastic stent, which can be left indefinitely, successfully avoiding possible stent migration and food impaction[1,11,13]. If a patient becomes a suitable candidate for cholecystectomy at any time, the option should be explored as it eliminates the risk of recurrent AC. Although there is limited discussion of cholecystectomy after EUS-GBD, reported cases have been successful[17]. As EUS-GBD becomes more widely adopted, consideration should be given to developing techniques that optimize subsequent surgery outcomes.

EUS-GBD is a valuable technique, but it is essential to identify contraindications and establish clear patient selection criteria. Contraindications to EUS-GBD may include uncontrolled coagulopathy or bleeding disorders, patients with severe anatomic variations making EUS-GBD technically challenging and patients with inaccessible gallbladders due to factors such as extensive adhesions or ascites. Moreover, patient selection for EUS-GBD should consider factors like the patient’s overall health, comorbidities, the extent of biliary obstruction, and the presence of conditions like Mirizzi syndrome. Imaging procedures, such as contrast-enhanced computed tomography or magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography, may play a crucial role in patient selection by assessing the anatomy, gallbladder wall characteristics, and biliary obstruction severity.

Furthermore, assessment of the gallbladder wall is a crucial aspect of EUS-GBD. During the procedure, attention should be paid to gallbladder wall thickness, presence of inflammation, and any signs of malignancy. This assessment helps in determining the feasibility of EUS-GBD and provides insights into the patient’s condition. Additionally, post-procedural follow-up is essential to monitor the effectiveness of EUS-GBD and detect any complications. This includes regular imaging studies, to assess stent patency, resolution of biliary obstruction, and any signs of AEs. Lastly, clinical evaluation should be performed to monitor the patient’s symptoms and overall well-being. Early detection and management of any issues are crucial for the long-term success of EUS-GBD.

PALLIATION OF MALIGNANT OBSTRUCTION

Malignant obstruction of the bile duct is a common cause of jaundice in patients with cancer. In these cases, the obstruction can result from tumor invasion, compression, or a combination of both. It occurs when a tumor obstructs the flow of bile from the liver, leading to a build-up of bilirubin in the bloodstream. This can cause a range of symptoms, including yellowing of the skin and eyes, itching, abdominal pain, and nausea. In severe cases, it can also lead to liver failure. Jaundice can cause significant morbidity and adversely affect the quality of life of patients, and prompt treatment is required to alleviate symptoms and prevent complications[1].

ERCP OR EUS BD

ERCP and EUS-BD are both minimally invasive endoscopic techniques that are used to manage biliary obstructions. ERCP has been the traditional technique used for BD, while EUS-BD has emerged as an alternative in recent years[10]. While both techniques aim to achieve the same outcome, there are differences in terms of their indications, success rates, and complications. ERCP is typically used for BD in cases of malignant biliary strictures using a transpapillary stent in plastic or metal[1,18]. Traditionally PTBD has been the mainstay of therapy for biliary decompression in patients with malignant obstruction in case of ERCP failure.

In a retrospective review by Sharaiha et al[19], the outcomes of EUS-BD and PTBD were compared in patients who had failed ERCP. Although both procedures showed similar technical success rates, EUS-BD resulted in fewer re-interventions, lower rates of late AEs, and less post-procedure pain compared to PTBD. In multivariable logistic regression analysis, EUS-BD was identified as the sole predictor for clinical success and long-term resolution. Based on these findings, the authors concluded that EUS-BD should be the preferred treatment option following a failed ERCP[19]. A network meta-analysis comparing different methods for draining distal malignant biliary obstrcution (DMBO) after failed ERCP found that PTBD was inferior to other interventions, while EUS-choledochoduodenostomy (EUS-CDS), EUS-guided hepaticogastrostomy, and surgical hepaticojejunostomy had comparable outcomes[20]. AE rates did not significantly differ among the interventions, although PTBD showed a slightly poorer performance. Overall, all interventions were effective for DMBO drainage.

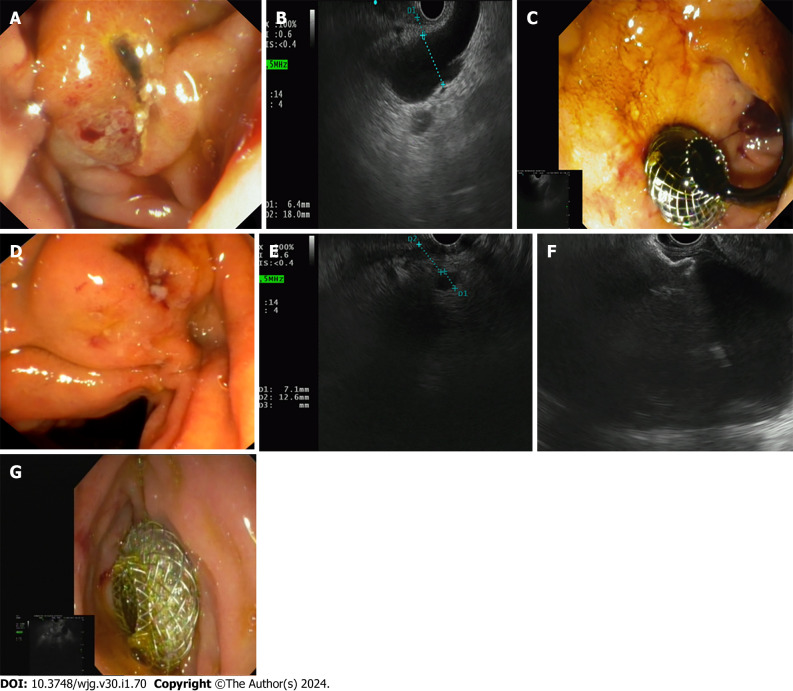

EUS-BD is indicated in cases where ERCP is not feasible due to an altered anatomy, previous surgery, or failed attempts at ERCP. EUS-CDS with LAMS is a viable and safe alternative for patients with DMBO who have failed ERCP (Figures 1A-C). In a retrospective analysis, was found that EUS-CDS with LAMSs achieved high rates of technical (93.3%) and clinical success (96.2%) in 256 patients. The procedure demonstrated acceptable AE rates (10.5%), with no fatal events reported. This study suggests that EUS-CDS with LAMSs can effectively manage DMBO after unsuccessful ERCP, providing clinicians with a valuable alternative technique and potentially reducing the need for invasive surgical interventions[21]. Both ERCP and EUS-BD have high success rates in achieving BD. The success rate of ERCP is reported to be between 85% to 95%, while the success rate of EUS-BD is reported to be between 80% to 95%[18]. However, the success rates of both techniques depend on various factors, such as the location and severity of the obstruction, the expertise of the endoscopist, and the availability of equipment and resources. In relation to challenging biliary cannulation, a specific study on BD in DMBO revealed that 56.4% of patients experienced difficulties in achieving successful cannulation, which consequently increased the risk of AEs. Furthermore, in this study, a failure in achieving biliary cannulation was observed in 80 (12,9%) out of 622 patients. This necessitated the implementation of alternative approaches to ensure effective BD[22].

Figure 1.

ERCP failure. A: Case of an infiltrated papilla causing endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) failure; B: Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)appearance of the dilated CBD (> 15 mm) with a short distance (< 10 mm) between the CBD and the duodenal wall; C: Endoscopic view of the lumen-apposing metal stents (LAMS) correctly placed in the duodenal bulb draining bile; D: Another case. of an infiltrated papilla causing ERCP. failure; E: EUS-BD was unfeasable due to CBD < 15 mm and the distance between the CBD and the duodenal wall > 10 mm; F: Rescue therapy with EUS-GBD was performed with first flange of the LAMS opening in the gallbladder lumen; G: Endoscopic view of the second flange of the LAMS correctly placed in the duodenal bulb.

Complications can occur with both ERCP and EUS-BD. The most common complications of ERCP include pancreatitis, bleeding, and infection. The reported rate of pancreatitis ranges from 2% to 9%, while the reported rate of bleeding ranges from 0.3% to 1%. The reported rate of infection is less than 1%. In contrast, the most common complications of EUS-BD include bleeding, bile peritonitis, and stent migration. The reported rate of bleeding ranges from 1% to 5%, while the reported rate of bile peritonitis ranges from 2% to 5%. The reported rate of stent migration is less than 1%[23,24]. In summary, both ERCP and EUS-BD are effective techniques for BD. ERCP is the preferred technique in cases where it is feasible, while EUS-BD is reserved for cases where ERCP is not possible. The question remains, what option exist when both techniques fail?

Additionally, it is important to note that classic conditions leading to ERCP failure include duodenal stenosis, infiltrating papilla, and other anatomical challenges that hinder successful cannulation and stent placement. Similarly, EUS-CDS may be limited by factors such as a low CBD diameter (< 15 mm) and a significant distance (> 10 mm) between the bulb and CBD, which can make the procedure technically challenging. These factors should be taken into consideration when evaluating the feasibility and success rates of EUS-GBD with LAMS as a rescue treatment for DMBO in patients who have failed both ERCP and EUS-CDS.

EUS-GBD: A RESCUE OPTION

EUS-GBD is a minimally invasive procedure which as it has been described has caught on for management of AC. Therefore, Imai et al[5] firstly described EUS-GBD as a rescue approach in patient with obstructive jaundice due to unresectable DMBO after ERCP failure. The authors reported a technical success rate of 100% and a functional success rate of 91.7% in 12 patients. The AEs rate was 16.7%, and the stent dysfunction rate was 8.3%. Finally the study concluded that EUS-GBD could be an alternative route for decompression of the biliary system when ERCP is unsuccessful[5]. Issa et al[4] conducted a multicenter retrospective study involving 28 patients with unresectable DMBO who underwent EUS-GBD between 2014 and 2019 after unsuccessful ERCP and EUS-BD. The technical success rate was 100%, and the clinical success rate was 92.6%, with a decrease in serum bilirubin of > 50% within two weeks. The AEs rate was 16.7%, and the delayed AEs included food impaction of the stent, cholecystitis, and bleeding. The Authors concluded that EUS-GBD is a feasible and safe rescue therapy for DMBO after failed ERCP and EUS-BD[4].

In a large multicenter retrospective analysis by Binda et al[25], the safety and effectiveness of EUS-GBD using LAMS as a rescue treatment for DMBO in patients who had failed both ERCP and EUS-CDS were evaluated. The study concluded that EUS-GBD with LAMS as a rescue treatment for DMBO showed high rates of technical and clinical success, with an acceptable rate of AEs[25] (Figures 1D-G). Please refer to Table 3 for comparative studies on EUS-GBD as a rescue approach. Kamal et al[2] conducted a meta-analysis of five studies with 104 patients to evaluate the efficacy and safety of EUS-GBD as a rescue therapy for malignant biliary obstruction in patients who have failed ERCP and EUS-BD. The pooled rates of clinical success and AEs were 85% and 13%, respectively. The study concluded that EUS-GBD is a safe and effective salvage therapy for achieving BD in patients with malignant biliary obstruction who have failed ERCP and EUS-BD. A recent study demonstrated a 100% clinical success rate with EC-LAMS placement in all patients undergoing EUS-GBD for palliative BD, making it a valid first-line option for low-survival patients with malignant jaundice. The study outlined that smaller diameter EC-LAMS should be the preferred choice to avoid food impaction and potential stent dysfunction[26]. Please refer to Table 4 for a comparison of the advantages and limitations of EUS-GBD with other drainage options.

Table 3.

Studies presenting procedural outcomes of endoscopic ultrasound-guided gallbladder drainage as a rescue approach

|

Ref.

|

Number of patients

|

Procedure

|

Technical success rate (%)

|

Clinical success rate (%)

|

Adverse events rate (%)

|

| Imai et al[5], 2016 | 12 | EUS-GBD with SEMS | 100 | 91.7 | 16.7 |

| Issa et al[4], 2021 | 28 | EUS-GBD with LAMS | 100 | 92.6 | 16.7 |

| Binda et al[25], 2023 | 48 | EUS-GBD with LAMS | 100 | 81.3 | 10.4 |

| Chang et al[33], 2019 | 9 | EUS-GBD with LAMS | 100 | 77.78 | 11.1 |

EUS-GBD: Endoscopic ultrasound-guided gallbladder drainage; LAMS: Lumen-apposing metal stents; SEMS: Self-expandable metal stents.

Table 4.

A table comparing the advantages and limitations of endoscopic ultrasound-guided gallbladder drainage with other drainage options in case of distal malignant biliary obstruction

|

Drainage option

|

Advantages

|

Limitations

|

| ERCP | Established technique, high success rates, can manage multiple strictures | Limited by anatomy, requires skilled operators, can cause pancreatitis |

| PTBD | High technical success rate, effective in cases of ERCP failure and altered anatomy | Associated with higher complication rates, requires external drainage, decreased quality of life, risk of multiple reintervention |

| EUS-BD | Access intrahepatic or extrahepatic duct, no risk of pancreatitis, can manage failed ERCP cases | Limited availability, requires skilled operators, higher cost |

| EUS-GBD | Can avoid transpapillary access, can manage acute cholecystitis, can manage failed ERCP and EUS-BD cases | Limited data on long-term outcomes, risk of gallbladder perforation or bleeding, limited applicability in cases of obstructed cystic duct |

EUS-GBD: Endoscopic ultrasound-guided gallbladder drainage; PTBD: Percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage; EUS-BD: Endoscopic ultrasound biliary drainage; ERCP: Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

Moreover, one of the primary safety concerns with EUS-GBD is the risk of bleeding. The gallbladder is a highly vascular organ, and during the drainage procedure, there is a risk of puncturing a blood vessel, which can lead to bleeding. The risk of bleeding is higher in patients with coagulopathy or those taking anticoagulant medications.

Other potential complications of EUS-GBD include bile leakage, perforation of the gallbladder, and post-procedural pain. However, the overall risk of complications is low, and the benefits of the procedure often outweigh the risks. While EUS-GBD can be an effective rescue technique, there are several potential limitations and challenges associated with the procedure. The location and anatomy of the gallbladder can vary significantly from patient to patient, making the procedure more challenging in some cases. Variations in the size and shape of the gallbladder, presence of the large-volume ascites, distance between gallbladder wall and gastrointestinal tract wall > 10 mm can also make it difficult to access and drain the bile. Patient selection is critical for the success of EUS-GBD. EUS-GBD may represent a possible alternative in case of failed of conventional approaches when cystic duct patency has been confirmed. Proper patient selection and risk assessment are important to ensure the safety and efficacy of the procedure.

The cost of EUS-GBD can be a limitation for some patients and healthcare systems. The procedure requires specialized equipment and resources, which can be expensive. The cost-effectiveness of the procedure should be carefully evaluated on a case-by-case basis. While EUS-GBD is becoming more widely available, it may still be unavailable in some regions or healthcare facilities. Patients in these areas may not have access to this treatment option, limiting their ability to receive palliative care. Another potential limitation of EUS-GBD is the need for specialized training. The procedure requires a high level of technical expertise and familiarity with EUS equipment and interventional techniques. However, the training and resources necessary to gain this expertise may be limited. Specialized training in EUS-GBD is not widely available, and only certain expert centers may offer the necessary training to endoscopists. These centers may be in limited geographic regions, making it difficult for some endoscopists to receive the necessary training. Furthermore, the training and resources required to become proficient in EUS-GBD can be costly, making it difficult for smaller healthcare facilities or endoscopists to incorporate this technique into their practice. The lack of access to specialized training and resources can limit the availability of EUS-GBD and the number of endoscopists who are able to perform the procedure.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, EUS-GBD has demonstrated impressive technical and clinical success rates with low rates of AEs, making it a safe and effective option for appropriate candidates who have exhausted conventional management[27]. Recently has been implemented to European Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy guidelines, as recommended therapy in AC in patients with high surgical risk. Also, was indicated as rescue procedure in patients with inoperable distal malignant biliary obstruction, when other endoscopic procedures have failed[27]. However, as each new alternative has some technical considerations, hence should be indicated only for meticulously selected group of patients.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: All the authors report no relevant conflicts of interest for this article.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Peer-review started: August 23, 2023

First decision: October 8, 2023

Article in press: December 22, 2023

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Italy

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Hu B, China; Seicean A, Romania; Shelat VG, Singapore S-Editor: Wang JJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Yu HG

Contributor Information

Alessandro Fugazza, Division of Gastroenterology and Digestive Endoscopy, Humanitas Research Hospital - IRCCS, Rozzano 20089, Milano, Italy.

Kareem Khalaf, Division of Gastroenterology, St. Michael’s Hospital, University of Toronto, Toronto M5B 1W8, ON, Canada.

Katarzyna M Pawlak, Division of Gastroenterology, St. Michael’s Hospital, University of Toronto, Toronto M5B 1W8, ON, Canada.

Marco Spadaccini, Division of Gastroenterology and Digestive Endoscopy, Humanitas Research Hospital - IRCCS, Rozzano 20089, Milano, Italy. marcospadaccini9@gmail.com.

Matteo Colombo, Division of Gastroenterology and Digestive Endoscopy, Humanitas Research Hospital - IRCCS, Rozzano 20089, Milano, Italy.

Marta Andreozzi, Division of Gastroenterology and Digestive Endoscopy, Humanitas Research Hospital - IRCCS, Rozzano 20089, Milano, Italy.

Marco Giacchetto, Division of Gastroenterology and Digestive Endoscopy, Humanitas Research Hospital - IRCCS, Rozzano 20089, Milano, Italy.

Silvia Carrara, Division of Gastroenterology and Digestive Endoscopy, Humanitas Research Hospital - IRCCS, Rozzano 20089, Milano, Italy.

Chiara Ferrari, Department of Anesthesia, Humanitas Research Hospital - IRCCS, Rozzano 20089, Milano, Italy.

Cecilia Binda, Gastroenterology and Digestive Endoscopy Unit, Forlì-Cesena Hospitals, Romagna 47121, Italy.

Benedetto Mangiavillano, Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Unit, Humanitas Mater Domini, Castellanza 21100, Italy.

Andrea Anderloni, Gastroenterology and Digestive Endoscopy Unit, Fondazione IRCCS Policlinico San Matteo, Pavia 27100, Italy.

Alessandro Repici, Division of Gastroenterology and Digestive Endoscopy, Humanitas Research Hospital - IRCCS, Rozzano 20089, Milano, Italy.

References

- 1.Fugazza A, Colombo M, Repici A, Anderloni A. Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Gallbladder Drainage: Current Perspectives. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2020;13:193–201. doi: 10.2147/CEG.S203626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kamal F, Khan MA, Lee-Smith W, Sharma S, Acharya A, Farooq U, Aziz M, Kouanda A, Dai SC, Munroe CA, Arain M, Adler DG. Efficacy and safety of EUS-guided gallbladder drainage for rescue treatment of malignant biliary obstruction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Endosc Ultrasound. 2023;12:8–15. doi: 10.4103/EUS-D-21-00206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khashab MA, Valeshabad AK, Afghani E, Singh VK, Kumbhari V, Messallam A, Saxena P, El Zein M, Lennon AM, Canto MI, Kalloo AN. A comparative evaluation of EUS-guided biliary drainage and percutaneous drainage in patients with distal malignant biliary obstruction and failed ERCP. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60:557–565. doi: 10.1007/s10620-014-3300-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Issa D, Irani S, Law R, Shah S, Bhalla S, Mahadev S, Hajifathalian K, Sampath K, Mukewar S, Carr-Locke DL, Khashab MA, Sharaiha RZ. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided gallbladder drainage as a rescue therapy for unresectable malignant biliary obstruction: a multicenter experience. Endoscopy. 2021;53:827–831. doi: 10.1055/a-1259-0349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Imai H, Kitano M, Omoto S, Kadosaka K, Kamata K, Miyata T, Yamao K, Sakamoto H, Harwani Y, Kudo M. EUS-guided gallbladder drainage for rescue treatment of malignant distal biliary obstruction after unsuccessful ERCP. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;84:147–151. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perez-Miranda M. Technical considerations in EUS-guided gallbladder drainage. Endosc Ultrasound. 2018;7:79–82. doi: 10.4103/eus.eus_5_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Widmer J, Alvarez P, Gaidhane M, Paddu N, Umrania H, Sharaiha R, Kahaleh M. Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided cholecystogastrostomy in patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer using anti-migratory metal stents: A new approach. Digest Endosc. 2014;26:599–602. doi: 10.1111/den.12163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de la Serna-Higuera C, Pérez-Miranda M, Gil-Simón P, Ruiz-Zorrilla R, Diez-Redondo P, Alcaide N, Sancho-del Val L, Nuñez-Rodriguez H. EUS-guided transenteric gallbladder drainage with a new fistula-forming, lumen-apposing metal stent. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;77:303–308. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raiter A, Szełemej J, Kozłowska-Petriczko K, Petriczko J, Pawlak KM. The complex advanced endoscopic approach in the treatment of choledocholitiasis and empyema of gallbladder. Endoscopy. 2022;54:E55–E56. doi: 10.1055/a-1352-2468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paduano D, Facciorusso A, De Marco A, Ofosu A, Auriemma F, Calabrese F, Tarantino I, Franchellucci G, Lisotti A, Fusaroli P, Repici A, Mangiavillano B. Endoscopic Ultrasound Guided Biliary Drainage in Malignant Distal Biliary Obstruction. Cancers (Basel) 2023;15 doi: 10.3390/cancers15020490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jain D, Bhandari BS, Agrawal N, Singhal S. Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Gallbladder Drainage Using a Lumen-Apposing Metal Stent for Acute Cholecystitis: A Systematic Review. Clin Endosc. 2018;51:450–462. doi: 10.5946/ce.2018.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.James TW, Baron TH. EUS-guided gallbladder drainage: A review of current practices and procedures. Endosc Ultrasound. 2019;8:S28–S34. doi: 10.4103/eus.eus_41_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Teh JL, Rimbas M, Larghi A, Teoh AYB. Endoscopic ultrasound in the management of acute cholecystitis. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2022;60-61:101806. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2022.101806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Posner H, Widmer J. EUS guided gallbladder drainage. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5:41. doi: 10.21037/tgh.2019.12.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kurihara H, Bunino FM, Fugazza A, Marrano E, Mauri G, Ceolin M, Lanza E, Colombo M, Facciorusso A, Repici A, Anderloni A. Endosonography-Guided Versus Percutaneous Gallbladder Drainage Versus Cholecystectomy in Fragile Patients with Acute Cholecystitis-A High-Volume Center Study. Medicina (Kaunas) 2022;58 doi: 10.3390/medicina58111647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boregowda U, Chen M, Saligram S. Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Gallbladder Drainage versus Percutaneous Gallbladder Drainage for Acute Cholecystitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Diagnostics (Basel) 2023;13 doi: 10.3390/diagnostics13040657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Flynn DJ, Memel Z, Hernandez-Barco Y, Visrodia KH, Casey BW, Krishnan K. Outcomes of EUS-guided transluminal gallbladder drainage in patients without cholecystitis. Endosc Ultrasound. 2021;10:381–386. doi: 10.4103/EUS-D-21-00040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hathorn KE, Bazarbashi AN, Sack JS, McCarty TR, Wang TJ, Chan WW, Thompson CC, Ryou M. EUS-guided biliary drainage is equivalent to ERCP for primary treatment of malignant distal biliary obstruction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Endosc Int Open. 2019;7:E1432–E1441. doi: 10.1055/a-0990-9488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sharaiha RZ, Kumta NA, Desai AP, DeFilippis EM, Gabr M, Sarkisian AM, Salgado S, Millman J, Benvenuto A, Cohen M, Tyberg A, Gaidhane M, Kahaleh M. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage versus percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage: predictors of successful outcome in patients who fail endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:5500–5505. doi: 10.1007/s00464-016-4913-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Facciorusso A, Mangiavillano B, Paduano D, Binda C, Crinò SF, Gkolfakis P, Ramai D, Fugazza A, Tarantino I, Lisotti A, Fusaroli P, Fabbri C, Anderloni A. Methods for Drainage of Distal Malignant Biliary Obstruction after ERCP Failure: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Cancers (Basel) 2022;14 doi: 10.3390/cancers14133291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fugazza A, Fabbri C, Di Mitri R, Petrone MC, Colombo M, Cugia L, Amato A, Forti E, Binda C, Maida M, Sinagra E, Repici A, Tarantino I, Anderloni A i-EUS Group. EUS-guided choledochoduodenostomy for malignant distal biliary obstruction after failed ERCP: a retrospective nationwide analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2022;95:896–904.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2021.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fugazza A, Troncone E, Amato A, Tarantino I, Iannone A, Donato G, D'Amico F, Mogavero G, Amata M, Fabbri C, Radaelli F, Occhipinti P, Repici A, Anderloni A. Difficult biliary cannulation in patients with distal malignant biliary obstruction: An underestimated problem? Dig Liver Dis. 2022;54:529–536. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2021.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paik WH, Lee TH, Park DH, Choi JH, Kim SO, Jang S, Kim DU, Shim JH, Song TJ, Lee SS, Seo DW, Lee SK, Kim MH. EUS-Guided Biliary Drainage Versus ERCP for the Primary Palliation of Malignant Biliary Obstruction: A Multicenter Randomized Clinical Trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113:987–997. doi: 10.1038/s41395-018-0122-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sharaiha RZ, Khan MA, Kamal F, Tyberg A, Tombazzi CR, Ali B, Tombazzi C, Kahaleh M. Efficacy and safety of EUS-guided biliary drainage in comparison with percutaneous biliary drainage when ERCP fails: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85:904–914. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2016.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Binda C, Anderloni A, Fugazza A, Amato A, de Nucci G, Redaelli A, Di Mitri R, Cugia L, Pollino V, Macchiarelli R, Mangiavillano B, Forti E, Brancaccio ML, Badas R, Maida M, Sinagra E, Repici A, Fabbri C, Tarantino I. EUS-guided gallbladder drainage using a lumen-apposing metal stent as rescue treatment for malignant distal biliary obstruction: a large multicenter experience. Gastrointest Endosc. 2023;98:765–773. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2023.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mangiavillano B, Moon JH, Facciorusso A, Vargas-Madrigal J, Di Matteo F, Rizzatti G, De Luca L, Forti E, Mutignani M, Al-Lehibi A, Paduano D, Bulajic M, Decembrino F, Auriemma F, Franchellucci G, De Marco A, Gentile C, Shin IS, Rea R, Massidda M, Calabrese F, Mirante VG, Ofosu A, Crinò SF, Hassan C, Repici A, Larghi A. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided gallbladder drainage as a first approach for jaundice palliation in unresectable malignant distal biliary obstruction: Prospective study. Dig Endosc. 2023 doi: 10.1111/den.14606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van der Merwe SW, van Wanrooij RLJ, Bronswijk M, Everett S, Lakhtakia S, Rimbas M, Hucl T, Kunda R, Badaoui A, Law R, Arcidiacono PG, Larghi A, Giovannini M, Khashab MA, Binmoeller KF, Barthet M, Perez-Miranda M, van Hooft JE. Therapeutic endoscopic ultrasound: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline. Endoscopy. 2022;54:185–205. doi: 10.1055/a-1717-1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jang JW, Lee SS, Song TJ, Hyun YS, Park DY, Seo DW, Lee SK, Kim MH, Yun SC. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided transmural and percutaneous transhepatic gallbladder drainage are comparable for acute cholecystitis. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:805–811. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.12.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kedia P, Sharaiha RZ, Kumta NA, Widmer J, Jamal-Kabani A, Weaver K, Benvenuto A, Millman J, Barve R, Gaidhane M, Kahaleh M. Endoscopic gallbladder drainage compared with percutaneous drainage. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82:1031–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.03.1912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Teoh AYB, Serna C, Penas I, Chong CCN, Perez-Miranda M, Ng EKW, Lau JYW. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided gallbladder drainage reduces adverse events compared with percutaneous cholecystostomy in patients who are unfit for cholecystectomy. Endoscopy. 2017;49:130–138. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-119036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Irani S, Ngamruengphong S, Teoh A, Will U, Nieto J, Abu Dayyeh BK, Gan SI, Larsen M, Yip HC, Topazian MD, Levy MJ, Thompson CC, Storm AC, Hajiyeva G, Ismail A, Chen YI, Bukhari M, Chavez YH, Kumbhari V, Khashab MA. Similar Efficacies of Endoscopic Ultrasound Gallbladder Drainage With a Lumen-Apposing Metal Stent Versus Percutaneous Transhepatic Gallbladder Drainage for Acute Cholecystitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:738–745. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tyberg A, Saumoy M, Sequeiros EV, Giovannini M, Artifon E, Teoh A, Nieto J, Desai AP, Kumta NA, Gaidhane M, Sharaiha RZ, Kahaleh M. EUS-guided Versus Percutaneous Gallbladder Drainage: Isn't It Time to Convert? J Clin Gastroenterol. 2018;52:79–84. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chang JI, Dong E, Kwok KK. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided transmural gallbladder drainage in malignant obstruction using a novel lumen-apposing stent: a case series (with video) Endosc Int Open. 2019;7:E655–E661. doi: 10.1055/a-0826-4309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]