Abstract

Monocytes/macrophages play a central role in mediating the effects of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) derived from gram-negative bacteria by the production of proinflammatory mediators. Recently, it was shown that the expression of cytokine genes for tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), and interferon-inducible protein-10 (IP-10) by murine macrophages in response to low concentrations of LPS is entirely CD14 dependent. In this report, we show that murine macrophages respond to low concentrations of LPS (≤2 ng/ml) in the complete absence of serum, leading to the induction of TNF-α and IL-1β genes. In contrast to the TNF-α and IL-1β genes, the IP-10 gene is poorly induced in the absence of serum. The addition of recombinant human soluble CD14 (rsCD14) had very little effect on the levels of serum-free, LPS-induced TNF-α, IL-1β, and IP-10 genes. In contrast, the addition of recombinant human LPS-binding protein (rLBP) had opposing effects on the LPS-induced TNF-α or IL-1β and IP-10 genes. rLBP inhibited LPS-induced TNF-α and IL-1β genes, while it reconstituted IP-10 gene expression to levels induced in the presence of serum. These results provide further evidence that the induction of TNF-α or IL-1β genes occurs via a pathway that is distinct from one that leads to the induction of the IP-10 gene and that the pathways diverge at the level of the initial interaction between LPS and cellular CD14. Additionally, the results presented here indicate that LPS structural analog antagonists Rhodobacter sphaeroides diphosphoryl lipid A and SDZ 880.431 are able to inhibit LPS-induced TNF-α and IL-1β in the absence of serum, while a synthetic analog of Rhodobacter capsulatus lipid A (B 975) requires both rsCD14 and rLBP to function as an inhibitor.

The cellular interaction of monocytes/macrophages with gram-negative bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) has been an area of intense research that has led to a current understanding of CD14 as a key LPS receptor. The CD14 molecule was first identified as a myeloid differentiation antigen found on the surface of peripheral blood monocytes and macrophages and later on neutrophils (12, 13). The finding that a plasma protein, LPS-binding protein (LBP), was able to bind LPS from both smooth and rough forms of bacteria and mediate attachment to macrophages provided the needed evidence for the existence of LPS receptors on cells (41, 42). This finding was followed by those of Wright et al. (43), who established that the membrane-bound CD14 molecule served as a receptor for complexes of LPS and LBP. Additional confirmation was provided by several investigators by the demonstration that the LPS responsiveness of non-CD14-expressing cells, such as 70Z/3 pre-B-lymphocytic cells (20) and Chinese hamster ovary cells (11), was increased by the expression of cellular CD14. Further confirmation of the CD14 molecule as an LPS receptor was provided by the generation of mice in which the CD14 gene was disrupted by gene targeting (16). Mice thus generated were ≥10 times more resistant to LPS than control wild-type mice receiving an equivalent dose of LPS. Unlike other cytokine and growth factor transmembrane receptors, the CD14 receptors on monocytes, macrophages, and neutrophils lack a transmembrane region and are anchored by a glycosylphosphatidylinositol linkage to the cell membrane (15). These findings have led to the proposal of a multimeric LPS receptor complex for LPS in which the CD14 molecule serves to concentrate LPS at the cell surface, while the other members of the multimeric complex function as signal transducers (reviewed in reference 37).

Much of the work generated in establishing CD14 as a receptor for low concentrations of LPS in human monocytes and neutrophils centers around the finding that a serum protein, LBP, is required for the initial interaction between low concentrations of LPS and the CD14 receptor. However, such a requirement for murine macrophages has not been proven definitively. Moreover, macrophages derived from humans and mice respond differently to lipid A analogs, such as lipid IVA (9, 10, 23, 33).

In this study, thioglycollate-elicited murine macrophages were cultured under totally serum-free conditions to investigate the requirement of serum factors for the induction of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), and interferon-inducible protein-10 (IP-10) genes by LPS. The induction of these three genes in response to low concentrations of LPS was previously demonstrated in CD14 knockout macrophages to be entirely CD14 dependent (27). We also determined whether serum factors were required for the inhibition of LPS-induced TNF-α and IL-1β genes by the LPS structural analog antagonists Rhodobacter sphaeroides diphosphoryl lipid A (RsDPLA), the Rhodobacter capsulatus lipid A synthetic analog B975-35-2 (B 975), and the synthetic LPS structural analog SDZ 880.431. We report that the murine macrophage response to low concentrations of LPS is different from the response observed with human monocytes in that substantial induction of TNF-α and IL-1β genes occurs in the complete absence of serum, whereas IP-10 gene expression is highly dependent on the presence of serum. Moreover, under serum-free conditions, recombinant human LBP (rLBP) reconstitutes LPS-induced IP-10 gene expression, whereas under these same conditions, down-regulation of the expression of both TNF-α and IL-1β genes is observed. Finally, the LPS response that results in the induction of TNF-α and IL-1β gene expression is inhibited by LPS structural analog antagonists RsDPLA and SDZ 880.431 in both the presence and the absence of serum, whereas B 975 requires both rLBP and recombinant human soluble CD14 (rsCD14) to function as an effective inhibitor in the absence of serum.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Macrophage culture conditions.

Four- to 6-week-old male and female C3H/OuJ mice (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, Maine) were injected intraperitoneally with 3 ml of 3% fluid thioglycolate. Four days later, peritoneal exudate cells were extracted by peritoneal lavage with 0.9% NaCl, washed once, and resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 2 mM glutamine, 30 mM HEPES, 0.3% NaHCO3, 100 IU of penicillin per ml, and 100 μg of streptomycin per ml (buffered RPMI medium). For total cellular RNA isolation, macrophages were cultured in six-well tissue culture dishes at 6.5 × 106 cells/well for 4 h to allow time for adherence before gentle washing to remove nonadherent cell types and then various treatments for 4 h. For serum-containing culture conditions, buffered RPMI medium was additionally supplemented with 2% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Hyclone, Logan, Utah).

This research was conducted according to the principles set forth in Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (16a).

Reagents.

Phenol-water-extracted Escherichia coli K235 LPS was prepared according to the method of McIntire et al. (22). A synthetic disaccharide analog of R. capsulatus lipid A (B 975) was obtained from Eisai Research Institute (Andover, Mass.). The tetrasodium salt of B 975 was solubilized in 10 mM NaOH, heated for 10 min at 50°C, and diluted further in a lactose (100 mg/ml)-phosphate (0.35 mg of NaH2PO4 · H2O per ml) buffer (pH 7) (500-μg/ml stock solution). The free-acid form of RsDPLA was prepared by acid hydrolysis of R. sphaeroides LPS as described previously (29), solubilized in 0.9% NaCl, and sonicated in a bath sonicator for 30 min before use (1-mg/ml stock solution). The water-soluble bis-Tris salt of SDZ 880.431 was synthesized by Sandoz Research Institute, Vienna, Austria, as described previously (34). SDZ 880.431 was solubilized initially in absolute ethanol and diluted further in 0.5% dextrose (2.5-mg/ml stock solution). rsCD14 and rLBP were generously provided by Henri S. Lichenstein (Amgen Boulder, Inc., Boulder, Colo.).

Isolation of total cellular RNA and Northern blot analysis.

Macrophages were subjected to various treatments for 4 h in buffered RPMI medium alone, buffered RPMI medium containing 2% FBS, or buffered RPMI medium supplemented with 100 ng of rsCD14 per ml, 100 ng of rLBP per ml, or both recombinant serum factors. Macrophages were then solubilized in 1 ml of RNA-STAT60 (Tel-Test, Friendswood, Tex.), and total cellular RNA was extracted according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Northern blot analysis was performed with the extracted RNA as detailed previously (27). The cDNA probes used for sequential probing of the blots were those specific for TNF-α (26), IL-1β (24), IP-10 (25), glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (6), or β-actin (35) genes. For the quantitation of genes, a PhosphorImager was used with Fast Scan software (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, Calif.). All gene expression data were calculated by first normalizing for one of the housekeeping genes, β-actin or GAPDH. Values were then expressed as a percentage of the response induced by 2 ng of LPS per ml in the presence of 2% FBS.

RESULTS

Response of thioglycollate-elicited murine macrophages to LPS in the presence and absence of serum.

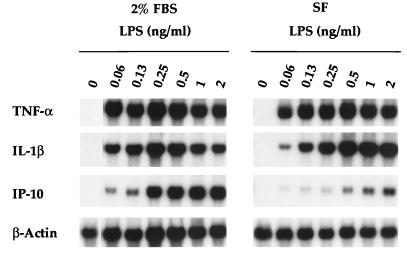

In experiments with macrophages from normal and CD14 knockout mice, it was demonstrated that the expression of cytokine TNF-α, IL-1β, and IP-10 genes by murine macrophages in response to low concentrations of LPS (∼1 mg/ml) is entirely CD14 dependent (27). To determine the extent to which the murine macrophage response to low concentrations of LPS is also dependent on serum factors, macrophages were isolated and cultured under serum-free conditions, and their responses were compared over a broad range of low LPS concentrations in the presence and absence of serum. Northern blot analysis was used to measure the expression of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IP-10 genes induced by LPS. Figure 1 illustrates that murine macrophages responded vigorously to LPS by expressing TNF-α and IL-1β mRNAs in the complete absence of serum. Levels of gene expression induced by 2 ng of LPS per ml under serum-free conditions were greater than or equal to those induced in the presence of 2% FBS. At <0.25 ng of LPS per ml, although TNF-α and IL-1β genes were expressed under serum-free conditions, the levels of steady-state mRNAs induced were somewhat lower in the absence than in the presence of serum. Based on two separate dose-response experiments in which 10-fold serial dilutions of LPS were used, the lowest concentration of LPS that resulted in the detectable expression of both TNF-α and IL-1β genes in both the presence and the absence of serum was 0.02 ng/ml (data not shown). In contrast to the inducibility of the TNF-α and IL-1β genes, the inducibility of the IP-10 gene by LPS in the absence of serum was much lower, even at the highest concentration of LPS tested. Thus, at these very low concentrations of LPS, induction of the IP-10 gene displays a clear requirement for serum factors, whereas induction of the TNF-α and IL-1β genes shows marginal serum factor dependence. Quantification of similar experiments by PhosphorImager analyses is provided in Fig. 2 and 3.

FIG. 1.

Induction of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IP-10 genes by murine macrophages stimulated by LPS in the presence and absence of serum. Northern blot analyses were performed on RNA extracted from macrophages treated with twofold serial dilutions of LPS in the presence (left panel) and absence (right panel) of 2% FBS as described in Materials and Methods. Data are from one of three similar experiments performed. SF, serum free.

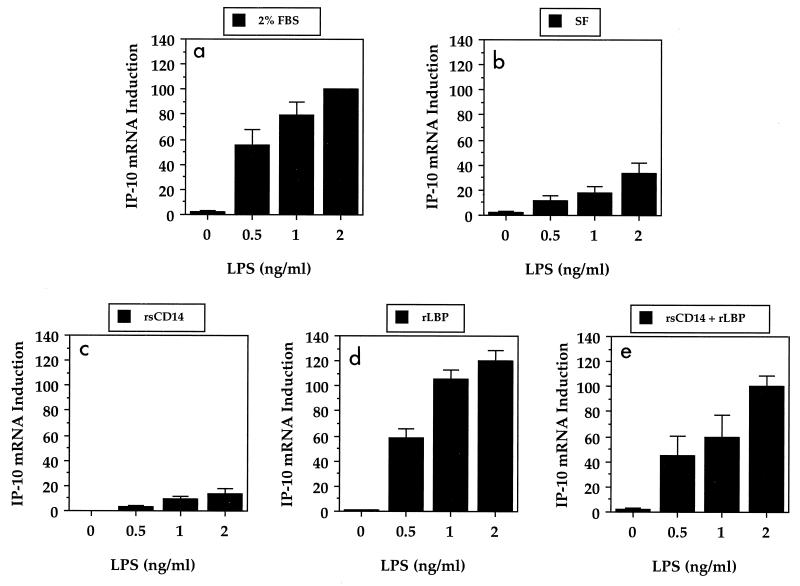

FIG. 2.

Effect of serum factors on LPS-induced IP-10 gene expression in murine macrophages. Macrophages were treated with the indicated concentrations of LPS in the presence and absence (SF, serum free) of 2% FBS or with serum-free medium supplemented with 100 ng of rsCD14 per ml and/or 100 ng of rLBP per ml. RNA was extracted and Northern blot analyses were performed as described in Materials and Methods. The gene induction data were normalized for β-actin before being expressed as a percentage of the response to 2 ng of LPS per ml in the presence of 2% FBS. The data represent the mean ± standard error of the mean from three separate experiments.

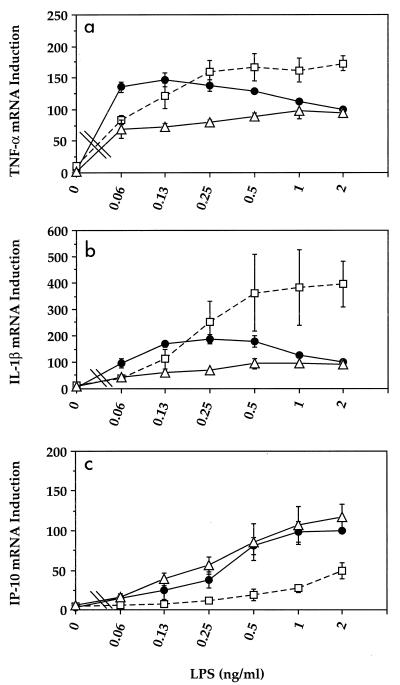

FIG. 3.

Effect of rLBP on LPS-induced TNF-α, IL-1β, and IP-10 genes in murine macrophages. Macrophages were treated with the indicated concentrations of LPS in the presence (•) or absence (□) of 2% FBS or in serum-free medium supplemented with 100 ng of rLBP per ml (▵). RNA was extracted and Northern blot analyses were preformed as described in Materials and Methods. The gene induction data were normalized for β-actin before being expressed as a percentage of the response to LPS in the presence of 2% FBS. The data represent the mean ± standard error of the mean from six separate experiments for 0.5 to 2 ng of LPS per ml and three separate experiments for <0.5 ng of LPS per ml.

Effect of rsCD14 and rLBP on LPS-induced TNF-α, IL-1β, and IP-10 genes in murine macrophages.

Since soluble CD14 and LBP are two serum proteins that have been well characterized for their abilities to influence the responsiveness of human monocytes, neutrophils, and endothelial cells to LPS, the role of these serum factors in the expression of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IP-10 genes by LPS-stimulated murine macrophages was next examined (3, 7, 14, 28). For these experiments, macrophages were treated for 4 h with LPS in serum-free medium supplemented with rsCD14 (100 ng/ml) and/or rLBP (100 ng/ml). rsCD14 had very little effect on the levels of TNF-α and IL-1β (data not shown) or IP-10 gene expression when compared to macrophages cultured and stimulated with LPS under serum-free conditions (Fig. 2b versus Fig. 2c). In contrast, the effect of rLBP was gene specific: rLBP was inhibitory for serum-free LPS-induced TNF-α and IL-1β genes (Fig. 3a and b), yet the same concentration of rLBP reconstituted the serum-free LPS-induced IP-10 gene response to levels that were comparable to those induced when macrophages were cultured in the presence of FBS (Fig. 2d and Fig. 3c). The combination of rsCD14 and rLBP had little effect on LPS-induced TNF-α and IL-1β (data not shown) or IP-10 (Fig. 2) gene expression when compared with rLBP alone. These data suggest that rLBP exerts opposing effects on LPS-induced IP-10 versus TNF-α and IL-1β gene expression.

Determination of the minimal concentration of rLBP required to reconstitute LPS-induced IP-10 gene expression and to inhibit TNF-α and IL-1β gene expression.

By keeping the concentration of LPS constant at 2 ng/ml, the minimal concentration of rLBP required to reconstitute the serum-free IP-10 gene response was determined. Table 1 illustrates that as little as 0.1 ng of rLBP per ml was able to enhance the LPS-induced IP-10 gene response over that seen under serum-free conditions. At least 1 ng of rLBP per ml was required to generate an IP-10 gene response comparable to that seen when macrophages were cultured in the presence of serum.

TABLE 1.

Effect of rLBP on LPS-induced TNF-α, IL-1β, and IP-10 genes in murine macrophages

| Treatment | Levela of:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| TNF-α | IL-1β | IP-10 | |

| 2 ng of LPS per ml + 2% FBS | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| 2 ng of LPSb | 172 ± 9 | 401 ± 83 | 44 ± 6 |

| 2 ng of LPS per ml + 0.1 ng of rLBP per mlb | 151 ± 18 | 327 ± 99 | 59 ± 12 |

| 2 ng of LPS per ml + 1 ng of rLBP per mlb | 135 ± 23 | 232 ± 94 | 122 ± 19c |

| 2 ng of LPS per ml + 10 ng of rLBP per mlb | 99 ± 5c | 109 ± 18c | 128 ± 13c |

| 2 ng of LPS per ml + 100 ng of rLBP per mlb | 94 ± 4c | 96 ± 9c | 110 ± 9c |

Arithmetic mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) from six separate experiments for LPS alone and LPS with 100 ng of rLBP per ml, arithmetic mean ± SEM from three separate experiments for LPS with 1 or 10 ng of rLBP per ml and LPS with FBS, and arithmetic mean ± SEM from two separate experiments for LPS with 0.1 ng of rLBP per ml. All values are percentages.

PhosphorImager data were normalized for the housekeeping gene β-actin before being expressed as a percentage of the LPS response in the presence of 2% FBS as described in Materials and Methods.

Significantly different (P ≤ 0.05) from value for LPS alone under serum-free conditions, as determined by an unpaired Student’s t test.

To determine the minimal concentration of rLBP that inhibited the TNF-α and IL-1β genes induced in response to LPS, the same Northern blots were reprobed for TNF-α and IL-1β genes. As shown in Table 1, 10 ng of rLBP per ml inhibited the expression of both TNF-α and IL-1β genes to levels induced by LPS in the presence of 2% FBS.

Examination of the requirement of serum factors for the antagonistic function of LPS disaccharide and monosaccharide structural analogs.

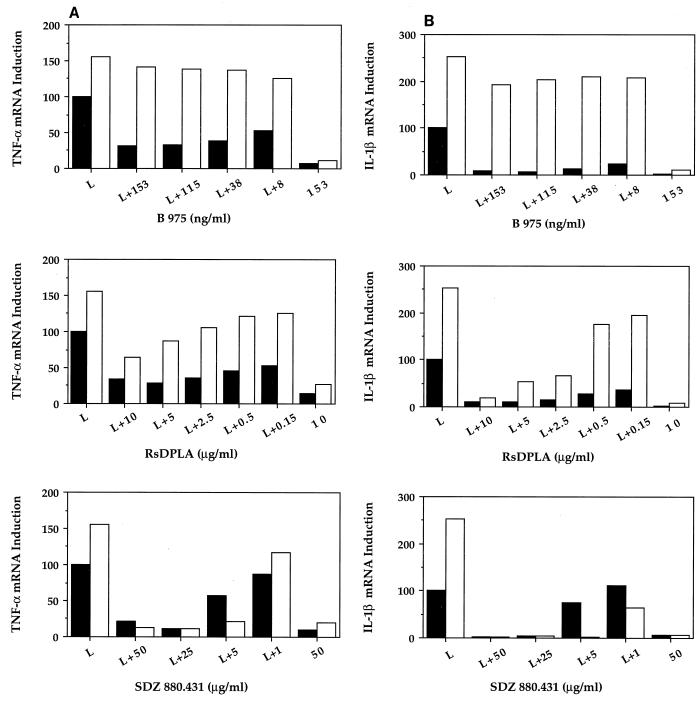

The requirement of serum factors for the inhibitory function of LPS structural analog antagonists was next examined. Macrophages were treated with a naturally occurring LPS disaccharide analog antagonist, RsDPLA, a synthetic LPS disaccharide analog antagonist, B 975, and a synthetic lipid A monosaccharide analog antagonist, SDZ 880.431, simultaneously with 2 ng of LPS per ml (Fig. 4). The LPS inhibitory effects of these antagonists were compared in the presence and absence of FBS. As shown in Fig. 5A and B, the inhibitory effects of the three structural antagonists differed greatly with regard to their potencies and requirements for serum. In the presence of serum, B 975 was the most potent of the three inhibitors tested, active in the nanogram-per-milliliter range. In the presence of serum, B 975 inhibited LPS-induced TNF-α (Fig. 5A) and IL-1β (Fig. 5B) gene expression at all concentrations tested. However, in the absence of serum, the inhibition of LPS-induced TNF-α and IL-1β gene expression by B 975 was minimal. Pretreatment of macrophages with RsDPLA or B 975 for 30 min before the addition of LPS in the presence and absence of serum yielded results that were similar to those obtained with the simultaneous addition of inhibitor and LPS (data not shown). Although high (microgram-per-milliliter) concentrations of both RsDPLA and SDZ 880.431 were required, both inhibited LPS-induced TNF-α and IL-1β gene expression to approximately the same extents in the presence and absence of serum. At lower concentrations, however, the inhibitory effects of RsDPLA were greater in the presence than in the absence of serum, whereas the opposite effect was observed with SDZ 880.431.

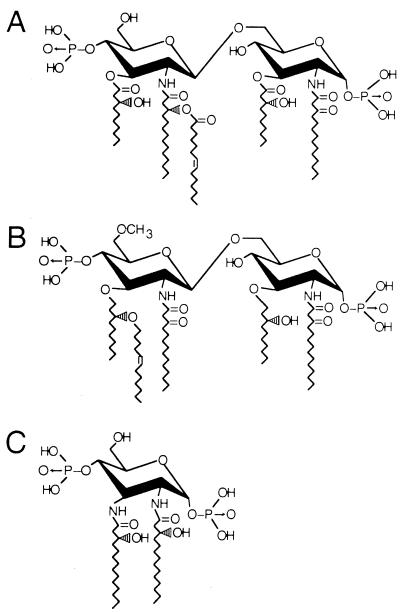

FIG. 4.

Chemical structures of LPS analog antagonists RsDPLA (A), B 975 (B), and SDZ 880.431 (C).

FIG. 5.

Comparison of the serum dependencies of LPS disaccharide and monosaccharide analog antagonists. Macrophages were treated with the indicated concentrations of B 975 (8 to 153 ng/ml), RsDPLA (0.15 to 10 μg/ml), and SDZ 880.431 (1 to 50 μg/ml) simultaneously with 2 ng of LPS per ml in the presence (▪) and absence (□) of 2% FBS. Northern blot analyses were then performed for TNF-α (A) and IL-1β (B) genes as described in Materials and Methods. The data represent the arithmetic mean from four similar experiments.

Determination of the serum factors required for the reconstitution of the LPS-induced inhibition of TNF-α and IL-1β genes by the synthetic LPS disaccharide analog antagonist B 975.

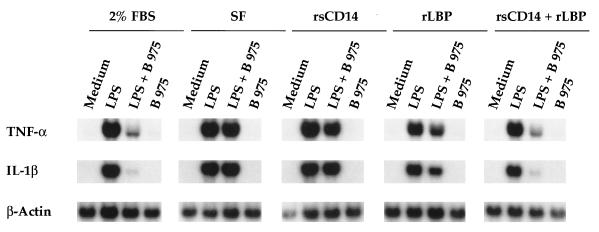

We next examined whether rsCD14 and rLBP, alone or in combination, could restore the inhibitory activity of B 975 under serum-free conditions. For these experiments, macrophages were treated with LPS (2 ng/ml) and B 975 (153 ng/ml) in the presence or absence of FBS or in serum-free medium supplemented with rsCD14 and/or rLBP. When macrophages were treated with LPS and B 975 in the absence of serum, B 975 showed only slight inhibition, at best, of LPS-induced TNF-α and IL-1β genes when compared to the levels of inhibition seen in the presence of serum (Fig. 6). Although slight inhibition of LPS-induced TNF-α and IL-1β genes was seen when B 975 was added simultaneously with LPS in the presence of either rsCD14 or rLBP, together these two serum factors acted in synergy to restore fully the inhibitory effect of B 975 on LPS-induced TNF-α and IL-1β gene expression (Fig. 6, compare first, second, and last panels).

FIG. 6.

The LPS structural antagonist B 975 requires both rsCD14 and rLBP to function as an inhibitor of LPS-induced TNF-α and IL-1β genes. Macrophages were treated with 2 ng of LPS per ml, 2 ng of LPS per ml and 153 ng of B 975 per ml, or 153 ng of B 975 per ml in the presence or absence (SF) of 2% FBS, with 100 ng of each serum factor per ml, or with both serum factors for 4 h before RNA was extracted and Northern blot analyses were performed as described in Materials and Methods. Data are from one of three similar experiments performed.

DISCUSSION

It is well established that the soluble plasma protein LBP enhances the responsiveness of human monocytes to picomolar concentrations of LPS (reviewed in reference 36). LBP, a secretory class 1 acute-phase protein that is synthesized primarily in the liver, functions as an LPS-binding, lipid transfer protein and delivers LPS to CD14 expressed on human monocytes (31, 32, 43). The LPS-enhancing effects of LBP that lead to cytokine release have been reported to result in the lowering of the stimulatory concentration of LPS by a factor of 100 to 1,000 in human phagocytes (reviewed in reference 36). In addition to LBP, normal serum and plasma have been reported to contain another multicomponent factor, septin, that enhances the effects of LPS on human phagocytes (44).

Here we report that in the total absence of serum, murine thioglycollate-elicited macrophages treated over a wide range of low concentrations of LPS express high levels of TNF-α and IL-1β mRNAs. The concentrations of LPS selected for this study were such that the TNF-α, IL-1β, and IP-10 genes induced by macrophages in response to LPS would be entirely CD14 dependent, based on a previous study with macrophages derived from CD14 knockout mice (27). The greatest observed difference between TNF-α levels and IL-1β levels expressed by macrophages cultured in the presence and absence of serum was only about twofold, even at the lowest concentration of LPS (0.02 ng/ml) that resulted in detectable gene expression. These results imply that the sensitivity of murine macrophages to LPS under serum-free conditions for TNF-α and IL-1β gene expression is significantly greater than has been reported for human monocytes. In contrast to the expression of the TNF-α and IL-1β genes, the expression of the IP-10 gene in the absence of serum was minimal at the lower concentrations of LPS tested and significantly lower in the absence than in the presence of serum, even at the highest concentration of LPS tested (2 ng/ml).

rLBP, but not rsCD14, enhanced LPS-induced IP-10 gene expression to levels comparable to those observed in the presence of 2% FBS at all concentrations of LPS tested yet inhibited the induction of both TNF-α and IL-1β genes in response to ≥0.5 ng of LPS per ml. These data suggest multiple roles for rLBP as a proinflammatory and antiinflammatory serum factor. Such a finding is not altogether surprising, since LBP shares 45% sequence identity with bactericidal/permeability-increasing protein (BPI), an LPS-neutralizing protein that is released from the primary granules of neutrophils during activation and lysis (39, 40). Although 1 ng of rLBP per ml was sufficient to enhance LPS-induced IP-10 gene expression and to inhibit TNF-α and IL-1β gene expression significantly, a high concentration of rLBP (100 ng/ml) was used in these studies to reflect the high level of LBP present in normal mouse plasma, which has been reported to be ∼2 μg/ml (8).

These data suggest that at the low concentrations of LPS used in these studies, which resulted in CD14-mediated macrophage activation and led to cytokine gene expression, LBP plays a dual role as a proinflammatory and antiinflammatory serum factor. For cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-1β, which require less LPS for triggering gene activation in murine macrophages, the dominant role of LBP might be that of an inhibitor that keeps in check the uncontrolled responses of macrophages to increasing LPS concentrations. For cytokines such as IP-10, which requires more LPS for induction by murine macrophages, the dominant role of LBP might be that of an enhancer. rsCD14 had very little effect on LPS-induced TNF-α, IL-1β, and IP-10 gene expression when used alone or when combined with rLBP under serum-free conditions. The observation that heterologous human rLBP alone was able to enhance the LPS-induced IP-10 gene response in murine macrophages to levels comparable to those induced by FBS-supplemented medium suggests similar roles for LBP in different species.

Our findings are also consistent with the recent findings of Amura et al. (2), who determined that while human LBP enhanced the production of TNF-α and IL-6 by human peripheral mononuclear cells in response to LPS, suppression of these cytokines was observed in murine macrophages under the same conditions. Previous studies also indicated that LBP plays a role in LPS clearance by transferring LPS to high-density lipoprotein, thereby limiting the cellular effects of LPS (45). Thus, LBP functions as a serum factor with multiple roles; the predominant role might be determined by the concentration of LBP at the site of action: systemic circulation, extravascular fluids, or sites of localized foci of infection.

Recently, the crystal structure of human BPI was resolved (4). Alignment of the amino acid sequences of the four members of the LPS-binding and lipid transfer family, namely, human BPI, LBP, cholesteryl ester transfer protein, and phospholipid transfer protein, indicated that structurally important residues were conserved in all four proteins. Although LBP has been demonstrated to enhance LPS-mediated effects in a number of cell types at low concentrations, the high concentrations of LBP found in the normal plasma of several species have led to uncertainty about its primary role under physiological conditions. Resolution of the crystal structure of LBP and the other two members of this family in the future should yield important information regarding the primary role of LBP among the multiple roles that have been assigned to it.

Although the signaling events subsequent to the transfer of LPS to membrane CD14 by LBP are as yet unknown, lipid A structural analog antagonists have been used to provide further insights into this process (reviewed in reference 21). Structural analog antagonists such as lipid IVA and deacylated LPS (in human monocytes) and RsDPLA (in human and murine monocytes/macrophages and neutrophils) are thought to compete with LPS for binding to specific structures on the cell membrane as well as to serum proteins LBP (1, 17) and soluble CD14 (17). However, studies by Kitchens et al. (19) and Kawata et al. (18) have suggested that inhibition by deacylated LPS and R. capsulatus lipid A, respectively, may occur under conditions in which the binding of LPS to membrane CD14 is not inhibited, suggesting that a site distal to the membrane CD14-LPS interaction may be the true site of action of LPS structural analog antagonists. This suggestion was further supported by studies by Delude et al. (5), who also determined that the site of inhibition by a synthetic RsDPLA was not membrane CD14. When the serum dependencies of the three structural analog antagonists used in this study were compared, it was found that the naturally occurring dissacharide analog antagonist RsDPLA and the synthetic monosaccharide analog antagonist SDZ 880.431 inhibited LPS-induced TNF-α and IL-1β gene expression in both the presence and the absence of serum in a dose-dependent manner. However, as the concentrations of the two inhibitors were decreased, their serum dependencies diverged: RsDPLA was a better inhibitor in the presence of serum than in the absence of serum, whereas SDZ 880.431 functioned better as an inhibitor under serum-free conditions. Interestingly, B 975, which is active at significantly lower concentrations than either RsDPLA or SDZ 880.431 in the presence of serum, failed to inhibit gene expression under serum-free conditions.

The differences in structure between natural RsDPLA and synthetic B 975 lie in the presence of a hydroxy or methoxy group at position C-6′, the position of the acyl chain with the acyloxyacyl side chain, and an ether rather than an ester linkage of C-3 and C-3′ acyl chains to the d-glucosamine disaccharide diphosphate backbone (Fig. 4). The addition of rsCD14 and rLBP to serum-free cultures resulted in the synergistic restoration of the LPS-inhibiting effects of B 975 to levels observed in the presence of serum (Fig. 6). That this effect cannot be simply attributed to a solubility problem for B 975 under serum-free conditions is supported by the finding that in the presence of a protein-containing, serum-free medium, Ex-cell 301 (R. J. H. BioSciences, Lenexa, Kans.), B 975 still failed to inhibit LPS-induced gene expression (data not shown). Since the protein concentration in Ex-cell 301 medium (100 μg/ml) was 500-fold greater than that in buffered RPMI medium containing rsCD14 and rLBP (i.e., 200 ng/ml), it seems unlikely that a difference in B 975 solubility can account for such striking functional differences. These findings may also reflect the lipophilicity of the three LPS antagonists, with SDZ 880.431 being the least and B 975 being the most lipophilic of the compounds examined. The other implication of this study is that synthetic B 975 may preferentially interact with soluble CD14 as opposed to membrane CD14, since LBP alone failed to restore fully the antagonism observed for this compound on CD14-bearing murine macrophages in the absence of serum. Alternatively, it is possible that the soluble CD14-B 975 complex has a greater capacity for interacting with (and blocking) the postulated membrane CD14-associated signaling receptor in the presence of rLBP than do membrane CD14-LPS complexes.

Schletter et al. (30) recently identified on human monocytes and endothelial cells an 80-kDa LPS-binding protein that required soluble CD14 and LBP for binding LPS. Since B 975 functions effectively as an LPS antagonist only in the presence of rsCD14 and rLBP, it is possible that its site of inhibition is at the murine equivalent of the human 80-kDa LPS-binding protein identified by Schletter et al. (30). More recently, another 216-kDa receptor that bound soluble CD14-LPS complexes was identified on several human cells, including monocytes (38). These authors also reported an interaction between the 216-kDa soluble CD14-LPS receptor and membrane CD14, providing yet another possible site for inhibition by LPS antagonists. Thus, the present findings that the LPS structural analog antagonists have different requirements for functioning as inhibitors may imply that their sites of action differ. Studies to identify the cellular targets of these LPS antagonists are under way.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants AI 18797 (to S.N.V.) and GM 50870 (to N.Q.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Aida Y, Kusumoto K, Nakatomi K, Takada H, Pabst M J, Maeda K. An analogue of lipid A and LPS from Rhodobacter sphaeroides inhibits neutrophil responses to LPS by blocking receptor recognition of LPS and by depleting LPS-binding protein in plasma. J Leukocyte Biol. 1995;58:675–682. doi: 10.1002/jlb.58.6.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amura C R, Chen L-C, Hirohashi N, Lei M-G, Morrison D C. Two functionally independent pathways for LPS-dependent activation of mouse peritoneal macrophages. J Immunol. 1997;159:5079–5083. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arditi M, Zhou J, Dorio R, Rong G W, Goyert S M, Kim K S. Endotoxin-mediated endothelial cell injury and activation: role of soluble CD14. Infect Immun. 1993;61:3149–3156. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.8.3149-3156.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beamer L J, Carrol S F, Eisenberg D. Crystal structure of human BPI and two bound phospholipids at 2.4 angstrom resolution. Science. 1997;276:1861–1864. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5320.1861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Delude R L, Savedra R, Jr, Zhao H, Thieringer R, Yamamoto S, Fenton M J, Golenbock D T. CD14 enhances cellular responses to endotoxin without imparting ligand-specific recognition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:9288–9292. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fort P, Marty L, Piechaczyk M, Sabrouty S E, Dani C, Jeanteur P, Blanchard J M. Various rat adult tissues express only one major mRNA species from the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate-dehydrogenase multigene family. Nucleic Acids Res. 1985;13:1431–1442. doi: 10.1093/nar/13.5.1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frey E A, Miller D S, Jahr T G, Sundan A, Bazil V, Espevik T, Finlay B B, Wright S D. Soluble CD14 participates in the response of cells to lipopolysaccharide. J Exp Med. 1992;176:1665–1671. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.6.1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gallay P, Heumann D, Roy D L, Barras C, Glauser M P. Lipopolysaccharide-binding protein as a major plasma protein responsible for endotoxemic shock. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:9935–9938. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.21.9935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Golenbock D T, Hampton R Y, Raetz C R H. Lipopolysaccharide antagonism by lipid A precursor IVA is species dependent. FASEB J. 1990;4:2097. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Golenbock D T, Hampton R Y, Qureshi N, Takayama K, Raetz C R H. Lipid A-like molecules that antagonize the effects of endotoxins on human monocytes. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:19490–19498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Golenbock D T, Liu Y, Millham F H, Freeman M W, Zoeller R A. Surface expression of human CD14 in Chinese hamster ovary fibroblasts imparts macrophage-like responsiveness to bacterial endotoxin. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:22055–22059. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goyert S M, Ferrero E, Rettig W J, Yenamandra A K, Obata F, Le Beau M M. The CD14 monocyte differentiation antigen maps to a region encoding growth factors and receptors. Science. 1988;239:497–500. doi: 10.1126/science.2448876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goyert S M, Ferrero E M, Seremetis S V, Winchester R J, Silver J, Mattison A C. Biochemistry and expression of myelomonocytic antigens. J Immunol. 1986;137:3909–3914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hailman E, Lichenstein H S, Wurfel M M, Miller D S, Jonson D A, Kelley M, Busse L A, Zukowski M M, Wright S D. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-binding protein accelerates the binding of LPS to CD14. J Exp Med. 1994;179:269–277. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.1.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haziot A, Chen S, Ferrero E, Low M G, Silber R, Goyert S M. The monocyte differentiation antigen, CD14, is anchored to the cell membrane by a phosphatidylinositol linkage. J Immunol. 1988;141:547–552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haziot A, Ferrero E, Kontgen F, Hijiya N, Yamamoto S, Silver J, Stewart C L, Goyert S M. Resistance to endotoxin shock and reduced dissemination of gram-negative bacteria in CD14-deficient mice. Immunity. 1996;4:407–414. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80254-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16a.Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources. Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals. National Research Council (DHEW) publication no. 85-23. Bethesda, Md: National Institutes of Health; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jarvis B W, Lichenstein H, Qureshi N. Diphosphoryl lipid A from Rhodobacter sphaeroides inhibits complexes that form in vitro between lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-binding protein, soluble CD14, and spectrally pure LPS. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3011–3016. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.8.3011-3016.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kawata T, Bristol J R, Rose J R, Rossignol D P, Christ W J, Asano O, Dubuc G R, Gavin W E, Hawkins L D, Kishi Y, McGuinness P D, Mullarkey M A, Perez M, Robidoux A L C, Wang Y, Kobayashi S, Kimura A, Katayama K, Yamatsu I. Anti-endotoxin activity of a novel synthetic lipid A analog. In: Levin J, Alving C R, Munford R S, Redl H, editors. Bacterial endotoxins. Lipopolysaccharides from genes to therapy. New York, N.Y: Wiley-Liss; 1995. pp. 499–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kitchens R L, Ulevitch R J, Munford R S. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) partial structures inhibit responses to LPS in a human macrophage cell line without inhibiting LPS uptake by a CD14-mediated pathway. J Exp Med. 1992;176:485–494. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.2.485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee J D, Kato K, Tobias P S, Kirkland T N, Ulevitch R J. Transfection of CD14 into 70Z/3 cells dramatically enhances the sensitivity to complexes of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and LPS binding protein. J Exp Med. 1992;175:1697–1705. doi: 10.1084/jem.175.6.1697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lynn W A, Golenbock D T. Lipopolysaccharide antagonists. Immunol Today. 1992;13:271–276. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(92)90009-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McIntire F C, Sievert H W, Barlow G H, Finley R A, Lee A Y. Chemical, physical, and biological properties of a lipopolysaccharide from Escherichia coli K-235. Biochemistry. 1967;6:2363–2372. doi: 10.1021/bi00860a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Munford R S, Hall C L. Detoxification of bacterial lipopolysaccharides (endotoxins) by human neutrophil enzyme. Science. 1986;234:203–205. doi: 10.1126/science.3529396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ohmori Y, Strassman G, Hamilton T A. cAMP differentially regulates expression of mRNA encoding IL-1α and IL-1β in murine peritoneal exudate macrophages. J Immunol. 1990;145:3333–3339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ohmori Y, Hamilton T A. A macrophage LPS-induced early gene encodes the murine homologue of IP-10. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990;168:1261–1267. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(90)91164-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pennica D, Hayflick J S, Bringman T S, Palladino M A, Goeddel D V. Cloning and expression in Escherichia coli of the cDNA for murine tumor necrosis factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:6060–6063. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.18.6060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perera P-Y, Vogel S N, Detore G R, Haziot A, Goyert S M. CD14-dependent and CD14-independent signaling pathways in murine macrophages from normal and CD14 knockout mice stimulated with lipopolysaccharide or Taxol. J Immunol. 1997;158:4422–4429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pugin J, Schurer-Maly C-C, Lecturcq D, Moriarty A, Ulevitch R J, Tobias P S. Lipopolysaccharide activation of human endothelial and epithelial cells is mediated by lipopolysaccharide-binding protein and soluble CD14. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:2744–2748. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.7.2744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qureshi N, Takayama K, Meyers K C, Kirkland T N, Bush C A, Chen L, Wang R, Cotter R J. Chemical reduction of 3-oxo and unsaturated groups in fatty acids of diphosphoryl lipid A from the lipopolysaccharide of Rhodopseudomonas sphaeroides: comparison of biological properties before and after reduction. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:6532–6538. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schletter J, Brade H, Brade L, Kruger C, Loppnow H, Kusumoto S, Rietschel E T, Flad H-D, Ulmer A J. Binding of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) to an 80-kilodalton membrane protein of human cells is mediated by soluble CD14 and LPS-binding protein. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2576–2580. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.7.2576-2580.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schumann R R, Leong S R, Flaggs G W, Gray P W, Wright S D, Tobias P S, Ulevitch R J. Structure and function of lipopolysaccharide binding protein. Science. 1990;249:1429–1431. doi: 10.1126/science.2402637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schumann R R, Kirschning C J, Unbehaun A, Aberle H, Knopf H-P, Lamping N, Ulevitch R J, Herrmann F. The lipopolysaccharide-binding protein is a secretory class 1 acute-phase protein whose gene is transcriptionally activated by APRF/STAT-3 and other cytokine-inducible nuclear proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:3490–3503. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.7.3490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sibley C, Terry A, Raetz C. Induction of κ light chain synthesis in 70Z/3 B lymphoma cells by chemically defined lipid A precursors. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:5098–5103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stuetz P L, Aschauer H, Hildebrandt J, Lam C, Loibner H, Macher I, Scholz D, Schuetze E, Vyplel H. Chemical synthesis of endotoxin analogues and some structure activity relationships. In: Nowotny A, Spitzer J J, Ziegler E J, editors. Endotoxin research series. 1. Cellular and molecular aspects of endotoxin reactions. New York, N.Y: Excerpta Medica; 1990. pp. 129–144. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Takunaga K, Taniguchi H, Yoda K, Shimizu M, Sakiyama S. Nucleotide sequence of a full-length cDNA for mouse cytoskeletal β-actin mRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1986;14:2829. doi: 10.1093/nar/14.6.2829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ulevitch R J. Recognition of bacterial endotoxins by receptor dependent mechanisms. Adv Immunol. 1993;53:267–289. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60502-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ulevitch R J, Tobias P S. Receptor-dependent mechanisms of cell stimulation by bacterial endotoxin. Annu Rev Immunol. 1995;13:437–457. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.13.040195.002253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vita N, Lefort S, Sozzani P, Reeb R, Richards S, Borysiewicz L K, Ferrara P, Labeta M O. Detection and biochemical characteristics of the receptor for complexes of soluble CD14 and bacterial lipopolysaccharide. J Immunol. 1997;158:3457–3462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weiss J, Elsbach P, Gazzano-Santoro H, Parent J B, Grinna L, Horwitz A, Theofan G. Bactericidal and endotoxin-neutralizing activities of the bactericidal/permeability-increasing protein and its bioactive N-terminal fragment. In: Levin J, Alvin C R, Munford R S, Stutz P L, editors. Bacterial endotoxin: recognition and effector mechanisms. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier Science Publishers B.V.; 1993. pp. 103–111. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wilde C G, Seilhamer J J, McGrogan M, Ashton N, Snable J L, Lane J C, Leong S R, Thornton M B, Miller K L, Scott R W, Marra M N. Bactericidal/permeability-increasing protein and lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-binding protein. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:17411–17416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wright S D, Jong M T C. Adhesion-promoting receptors on human macrophages recognize Escherichia coli by binding to lipopolysaccharide. J Exp Med. 1986;164:1876–1888. doi: 10.1084/jem.164.6.1876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wright S D, Tobias P S, Ulevitch R J, Ramos R A. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) binding protein opsonizes LPS-bearing particles for recognition by a novel receptor on macrophages. J Exp Med. 1989;170:1231–1241. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.4.1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wright S D, Ramos R A, Tobias P T, Ulevitch R J, Mathison J C. CD14, a receptor for complexes of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and LPS binding protein. Science. 1990;249:1431–1433. doi: 10.1126/science.1698311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wright S D, Ramos R A, Patel M, Miller D S. Septin: a factor in plasma that opsonizes lipopolysaccharide-bearing particles for recognition by CD14 on phagocytes. J Exp Med. 1992;176:719–727. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.3.719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wurfel M M, Kunitake S T, Lichenstein H, Kane J P, Wright S D. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-binding protein is carried on lipoproteins and acts as a cofactor in the neutralization of LPS. J Exp Med. 1994;180:1025–1035. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.3.1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]