Abstract

Objectives

This study aimed to examine the prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in victims-survivors of intimate partner violence (IPV) consulting at the specialised and original facility ‘Maison des Femmes’ (MdF) or in two close municipal health centres (MHCs).

Design

A mixed-methods study using a convergent parallel design from July 2020 to June 2021.

Setting/participants

A questionnaire was proposed to women aged 18 years and over having suffered from IPV, in the MdF and in two MHCs. We also conducted qualitative interviews with a subsample of the women, asking for victim-survivors’ perceptions of the effect of the MdF’s care.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

The presence of a PTSD using the PTSD self-report checklist of symptoms, possibility of reaching women by phone 6 months after the inclusion visit, level of self-rated global health, number of emergency visits in the past 6 months, substances use, readiness to change and safety behaviours.

Results

A total of 67 women (mean age: 34 years (SD=9.7)) responded to our questionnaire. PTSD diagnosis was retained for 40 women (59.7%). Around 30% of participants self-rated their global health as bad. Less than 30% (n=18) of women were regular smokers, and only 7.5% of participants had a problematic alcohol use (Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test-Consumption score ≥4), 19.4% women used psychotropic drugs. Six months after inclusion, half of participants had been reached by phone. Analysis of the qualitative interviews clarified victim-survivors’ perceptions of the MdF’s specific care: social networking, multidisciplinary approach, specialised listening, healthcare facilities, evasion and ‘feeling at home’.

Conclusions

The high prevalence of PTSD at inclusion was nearly the same between the three centres. This mixed-methods comparison will serve as a pilot study for a larger comparative trial to assess the long-term impact of the MdF’s specialised care on victims-survivors’ mental health, compared with the care of uncoordinated structures.

Trial registration number

Keywords: MENTAL HEALTH, GYNAECOLOGY, EPIDEMIOLOGY

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

This is the first study to assess the prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder among victim-survivors of intimate partner violence attending France’s first facility dedicated to the treatment of violence against women: the Maison des Femmes.

The study has the advantage of combining quantitative and qualitative methods to consider the possibility of a larger-scale trial.

We were able to consider women in situations of violence and precariousness who are difficult to interview in practice (safety, confidentiality, shame, etc).

However, this study lacks information on other traumatic events experienced by the respondents and on the duration and/or repetition of the violence.

Health outcomes measured in this study are based solely on the women’s self-reported perceptions, rather than on possibly more valid clinical observations.

Introduction

According to the WHO, violence against women (VaW) is a global public health matter with significant physical and mental health-related consequences for the victims.1 Intimate partner violence (IPV) is the most widespread form of VaW.2 Worldwide, around 30% of girls and women aged 15 and older have experienced IPV in their lifetime.3 IPV is associated with an increased risk of developing numerous short and long-term adverse psychological outcomes, including depression, generalised anxiety disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD),4 a psychiatric disorder that may occur in people who have experienced, or witnessed, a traumatic event.5

Women who experienced violence have specific needs, arising from the often-repeated and complex nature of the trauma.6 They also tend to accumulate other risk factors for poor mental health, such as economic insecurity, parenting stress and social isolation.7 In France, victims-survivors of IPV, especially the most socially disadvantaged ones, face multiple barriers to healthcare access.8 Particularly, there is a lack of dedicated care facilities and providers trained in caring for these women’s specific medical, psychosocial, parenting and judicial needs. French health professionals are strongly encouraged to ask their female patients about any experience of physical or sexual violence.9 However, they have rarely received the specific training to deal with these issues with confidence and professionalism, and often lack the resources to refer women victims of IPV to appropriate care facilities and health providers.

As described in a recent publication,10 La Maison des Femmes (MdF, Women’s Home), established in 2016, is a medical and social structure specifically dedicated to provide individualised multidisciplinary care for victims-survivors of VaW, such as IPV. It offers care combining health, social and judicial aspects in a single structure. The MdF consists of three units: a family planning centre (FPC, consultations for contraception and abortions), a violence care unit (composed of psychiatrist, general practitioners, midwives, psychologists, social workers, lawyers, police officers and support groups) and a female genital mutilation care unit (surgeons and sex therapists). The MdF is located in the poorest department in mainland France, Seine-Saint-Denis, a department right next to Paris, where one in four women attending the FPCs suffers, or has suffered, from IPV.10

Several structures providing coordinated multidisciplinary care, directly inspired by the model of the Saint Denis women’s centre, have been created in France. As the economic model has not yet been established, the question arises of evaluating the service provided by these coordinated care structures, particularly in terms of their capacity to improve the mental health and reduce the post-traumatic stress of women victims of IPV.

The main objective of this study was to examine individual characteristics, and the prevalence of PTSD, in victims-survivors of IPV consulting at the MdF or in two other municipal health centres (MHCs) located in the same area of the Paris conurbation.

Methods

Data source and study population

We carried out surveys from July 2020 to June 2021 in three FPCs: one in the Mdf and two in MHC from the same department (MHC-1 in Saint Denis and MHC-2 in Aubervilliers).

All women aged 18 years and over consulting in one of the three FPCs, having suffered or suffering from IPV and able to understand the objectives of the study, were eligible (interpreters could be contacted by phone if necessary). Trained research assistants (RAs) were available in each of the study centres to screen women for eligibility, explain the study and ask for a written informed consent before recruitment. Women under 18 years old or under tutorship were excluded. RA also assisted participants in completing the questionnaire.

We contacted each participant by telephone 6 months later.

Patient and public involvement

For security and confidentiality reasons, it was not appropriate or possible to involve patients or the public in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of our research.

Outcome measures

Data were collected using a self-administered questionnaire that included questions about participants’ sociodemographic characteristics, as well as a range of health and substance use data.

The main outcome was a PTSD diagnosis, measured using the PTSD self-report checklist of 20 PTSD symptoms defined in the DSM-5 (PCL-5).11 PCL-5 is a widely used self-administrated questionnaire to detect and evaluate a PTSD, with a validated French version.12 Each item on this scale is rated on a 5-point Likert scale reflecting severity of a particular symptom from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely) during the past month, with a threshold score of 33.

Other outcomes included: the possibility of reaching women by phone 6 months after the inclusion visit, the level of self-rated global health (Likert scale: ‘very good’, ‘good’, ‘quite good’, ‘bad’ and ‘very bad’), the self-reported number of emergency visits in the past 6 months, the substances use: smoking status, alcohol (evaluated by the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test-Consumption/AUDIT-C13), drugs (‘Did you use hypnotics, sleep pills, antidepressants or anxiolytics in the past 6 months?’), the readiness to change, the safety behaviours (evaluated by questions inspired by the safety behaviour checklist14) and the help seeking behaviours in the past 6 months (evaluated by questions inspired by Van Parys et al15).

Qualitative interviews

We conducted semistructured interviews with a subsample of the participants in the MdF and in the MHC-1, according to the grounded theory (the interview guide is available in online supplemental figure). The interviews were all conducted by the same researcher, an MD qualified in qualitative research who used an interview guide. The interview guide was developed by the coauthors and reviewed and tested by two psychologists and one social researcher to verify the comprehensibility of the questions. The guide included questions about history of violence, women’s perception of the effect of the care provided at MdF and in the MHCs, women’s perception of their needs and their mental and physical health. Interviews were anonymised, transcribed, analysed and interpreted following practical guidance for conducting qualitative research.16

bmjopen-2023-075552supp001.pdf (61.3KB, pdf)

As recommended by the WHO, our study paid particular attention to minimising the risk affecting the safety of the respondents: confidentiality, safe climate at all time, informed consent, and basic care and support available locally for victims-survivors.17

Analysis

This mixed-method study used a convergent parallel design.18 Quantitative data analysis was conducted using SAS for Windows (V.9.4). To describe the sociodemographic characteristics, perceived social support, health and substance use indicators descriptive statistics were used consisting of frequency, percentage, and mean and SD.

As concerned the qualitative interviews, we conducted an inductive content analysis using a grounded theory approach.19 The qualitative data were analysed with NVivo V.12 software. The transcribed text was coded, then the codes were sorted into categories and main themes and were illustrated using verbatim quotations. We used a checklist of quality criteria (ie, credibility, dependability, conformability, transferability and authenticity) to improve the trustworthiness of our results.19

Results

Sample description

A total of 67 women responded to our questionnaire: 40 in the MdF, 12 in the MHC-1 and 15 in the MHC-2.

The characteristics of study participants are described in table 1 (more detailed characteristics are described in online supplemental table 1). The majority of the participants (57%) were aged below 35 years, with a mean age of 34 (SD=9.7), and had at least one child (73.1%). Slightly more than half of participants (53.0%) were not born in France. Around 25% of participants (n=17) declared having no one to turn to for help or assistance if they needed it, while more than one-third (n=25) had at least two people to turn to for help.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of study participants (n=67)

| ALL N=67 % (n) |

Maison des Femmes N=40 % (n) |

MHC-1 N=12 % (n) |

MHC-2 N=15 % (n) |

|

| Age (years) (n=67) | ||||

| Mean (SD, range) | 34.1 (9.7, 18–71) | 31.3 (8.2, 18–71) | 40.3 (8.7, 29–55) | 36.5 (10.0, 21–52) |

| Median | 33 | 29 | 37 | 37 |

| Ages (years, 4 classes) | ||||

| 18–24 | 14.9 (10) | 20.0 (8) | 0 (0) | 13.3 (2) |

| 25–34 | 41.8 (28) | 52.5 (21) | 25.0 (3) | 26.7 (4) |

| 35–49 | 34.3 (23) | 25.0 (10) | 50.0 (6) | 46.7 (7) |

| ≥50 | 9.0 (6) | 2.5 (1) | 25.0 (3) | 13.3 (2) |

| In a couple (n=67) | ||||

| Yes | 49.2 (33) | 50.0 (20) | 50.0 (6) | 46.7 (7) |

| Has children (n=67) | ||||

| Yes | 73.1 (49) | 67.5 (27) | 83.3 (10) | 80.0 (12) |

| Born in France (n=66) | ||||

| Yes | 47.0 (31) | 43.6 (17) | 50.0 (6) | 53.3 (8) |

| Health coverage (n=67) | ||||

| Health insurance | 44.8 (30) | 37.5 (15) | 66.7 (8) | 46.7 (7) |

| Social security | 17.9 (12) | 22.5 (9) | 0 (0) | 20.0 (3) |

| Universal health coverage | 25.4 (17) | 30.0 (12) | 16.7 (2) | 20.0 (3) |

| State medical assistance | 4.5 (3) | 0 (0) | 16.7 (2) | 6.7 (1) |

| No coverage | 7.5 (5) | 10.0 (4) | 0 (0) | 6.7 (1) |

| Professional situation (n=66) | ||||

| Inactive | 39.4 (26) | 38.5 (15) | 16.7 (2) | 60.0 (9) |

| Unemployed | 13.6 (9) | 10.3 (4) | 25.0 (3) | 13.3 (2) |

| Working | 37.9 (25) | 38.5 (15) | 58.3 (7) | 20.0 (3) |

| Student | 9.1 (6) | 12.8 (5) | 0 (0) | 6.7 (1) |

| Support (n=67) | ||||

| No one | 25.4 (17) | 22.5 (9) | 33.3 (4) | 26.7 (4) |

| One people | 37.3 (25) | 45.0 (18) | 25.0 (3) | 26.7 (4) |

| At least two peoples | 37.3 (25) | 32.5 (13) | 41.7 (5) | 46.7 (7) |

| Number of women who can be reached by phone 6 months after inclusion | 52.2 (35) | 65.0 (26) | 25.0 (3) | 40.0 (6) |

| Safety precaution (n=67) | ||||

| 1 | 3.0 (2) | 2.5 (1) | 8.3 (1) | 0 (0) |

| 2 | 10.6 (7) | 10.0 (4) | 8.3 (1) | 14.3 (2) |

| 3 | 19.7 (13) | 17.5 (7) | 25.0 (3) | 21.4 (3) |

| 4 (none) | 66.7 (44) | 70.0 (28) | 58.3 (7) | 64.3 (9) |

| Willingness to change (n=67) | ||||

| 0 (none) | 26.9 (18) | 27.5 (11) | 25.0 (3) | 26.7 (4) |

| 1 | 23.9 (16) | 27.5 (11) | 25.0 (3) | 13.3 (2) |

| 2 | 49.3 (33) | 45.0 (18) | 50.0 (6) | 60.0 (9) |

| Help seeking (n=67) | ||||

| 0 (none) | 10.5 (7) | 17.5 (7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 1 | 22.4 (15) | 20.0 (8) | 16.7 (2) | 33.3 (5) |

| 2 | 19.4 (13) | 20.0 (8) | 33.3 (4) | 6.7 (1) |

| 3 | 25.4 (17) | 22.5 (9) | 33.3 (4) | 26.7 (4) |

| 4 | 9.0 (6) | 7.5 (3) | 0 (0) | 20.0 (3) |

| 5 | 6.0 (4) | 5.0 (2) | 16.7 (2) | 0 (0) |

| 6 | 7.5 (5) | 7.5 (3) | 0 (0) | 13.3 (2) |

MHC, municipal health centre.

bmjopen-2023-075552supp002.pdf (79.3KB, pdf)

Six months after inclusion, half of participants (52.2%) had been reached by phone (65.0% in MdF, 25.0% in MHC-1 and 40.0% in MHC-2).

Prevalence of PTSD

Participants reported an average PCL-5 score of 37.1 (SD = 16.6) (table 2). Forty women (59.7%) had a PCL-5 score of at least 33, which is the accepted cut-off value for defining the presence of PTSD diagnosis (table 2). The prevalence of PTSD was quite similar between the three groups.

Table 2.

Medical characteristics of study participants (n=67)

| ALL N=67 % (n) |

Maison des Femmes N=40 % (n) |

MHC-1 N=12 % (n) |

MHC-2 N=15 % (n) |

|

| PCL-5 | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 37.1 (16.6) | 37.7 (18.1) | 35.7 (13.7) | 36.9 (15.6) |

| Score ≥33 | 59.7 (40) | 57.5 (23) | 60.0 (9) | 66.7 (8) |

| Self-rated global health | ||||

| Very bad | 10.6 (7) | 12.5 (5) | 9.0 (1) | 6.7 (1) |

| Bad | 23.3 (16) | 20.0 (8) | 36.4 (4) | 26.7 (4) |

| Quite good | 25.8 (17) | 25.0 (10) | 27.3 (3) | 26.7 (4) |

| Good | 31.8 (21) | 35.0 (14) | 18.2 (2) | 33.3 (5) |

| Very good | 7.6 (5) | 7.5 (3) | 9.0 (1) | 6.7 (1) |

| Emergency room visit(s) in the past 6 months | ||||

| Yes | 40.3 (27) | 47.5 (19) | 25.0 (3) | 33.3 (5) |

| Active smoker | ||||

| Yes | 26.9 (18) | 27.5 (11) | 33.3 (5) | 16.7 (2) |

| AUDIT-C≥4 | ||||

| Yes | 7.5 (5) | 10.0 (4) | 6.7 (1) | 0 |

| Use of psychotropic drugs | ||||

| Yes | 19.4 (13) | 20.0 (8) | 20.0 (3) | 16.7 (2) |

AUDIT-C, Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test-Consumption; MHC, municipal health centre; PCL-5, PTSD Checklist for DSM-5; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder.

Health and substance use outcomes

Around 40% of participants (n=26) self-rated their global health as a good or very good. The same percentage of participants reported consulting at an emergency room in the past 6 months.

Less than 30% (n=18) of women were regular smokers, and only 7.5% of participants had a problematic alcohol use with an AUDIT-C score greater than or equal to 4, one out of five women used psychotropic drugs.

Qualitative data

For this pilot study, nine women were interviewed (six in the MdF, three in the MHC-1) (online supplemental table 2).

They were aged 27–55 years old (mean age: 38.8), six were employed. Seven women had at least one child. Only one was in a couple, and they suffered from domestic violence between 1.5 and 13 years (mean: 5.4 years).

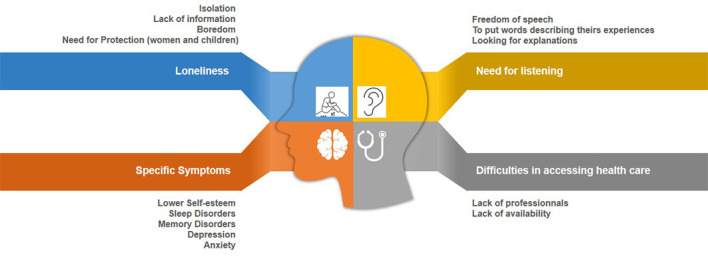

With regard to the perception of difficulties encountered by the women victims of violence, four main themes emerged from the thematic analysis: a feeling of loneliness, the need to be listened to, the specificity of the symptoms of the victims-survivors and the difficulties in accessing healthcare (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Perception of the difficulties encountered by the victims-survivors of violence.

I spend all day long alone like this, with my thoughts, I don’t know where to go, and I’m still turning in circles… (MHC1)

In fact I think we should be in a bubble with psychologists all the time [laughs] to be listened and to feel that we’re not alone. (MHC2)

We need real professionals, who understand what we’re going through (MdF5)

I wanted to go to another support group but I’ve been told that I have to wait because there are too many people… I cried not because there was no room for me but because we are so many, and there is no room for anyone… (MdF3)

With regard to the perception of the specific care of the MdF, six main themes emerged. Four of them correspond to the four themes developed in figure 1: social networking, multidisciplinary approach, specialised listening, healthcare facilities and the other two themes highlight additional advantages provided by the MdF: evasion and ‘feeling at home’ (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Perceptions of the specific care of the Maison des Femmes.

We live in a society where we are forced to believe that women are our competitors… But here we are sisters. (MdF5)

That’s what interested me here, being able to get out of my head and to concentrate on a physical activity […] it makes it possible to find an appeasement, what I call a “air bubble” so I can restart (MdF4)

I’m in a house here, it’s a house that is made for us […]. There’s a roof like a house, I mean it’s friendly, at first I said to myself “what am I doing here?” […] and finally every time I come I can say everything, I feel like it won’t come out the walls, I feel like whatever I say I won’t be judged. (MdF6).

Discussion

This study highlights the very substantial (60%) prevalence of PTSD symptoms in a sample of women who have experienced IPV and consulting at FPCs in the Parisian region.

Our results have showed that the proportion of women suffering from PTSD is not different according to the care structure and have outlined the recruitment capacity for a future larger study.

Prevalence of PTSD

These results are consistent with those reported by other authors who have described an association between the exposure to IPV and the presence of PTSD.20 21 The prevalence of PTSD among victims-survivors of IPV varies depending on the studies and on the tool used to quantify PTSD, ranging from 33% to 84%, with a mean of 61%.22

To assess the benefit of a multidisciplinary and cooperated approach on the mental health of the victims-survivors, as the MdF provides, a comparison between the three centres a few months after the inclusion with a repeated measure of PTSD would be advisable. The fact that the prevalence of PTSD at inclusion is almost the same between the three centres in our study seems to eliminate centre bias, and encourages us to consider a larger comparative study aimed at comparing the long-term impact of the MdF on the mental health of victim-survivors with that of standard-of-care structures. This study, the IROND-L study (‘Evaluation of the impact of the care of women victims of sexist and sexual violence, according to a coordinated multidisciplinary approach in women’s homes or traditional health centres or family planning, on mental and physical health: a prospective, quasi-experimental, multicentre, national study’), has just been funded by the French Ministry for Health, submitted to an ethic committee and is likely to start early in 2024. We were unable to contact a majority of women from the MHCs 6 months after inclusion, whereas two out of three women from the MdF had been reached. This could reinforce the fact that women may value the care provided by the MdF more than that provided by non-dedicated structures, but it will present an additional difficulty for a subsequent comparative study.

A multicomponent model

The MdF is a structure that provides multicomponent trauma-informed and holistic care. Getting out of IPV is a process with multiple stages.23 Our qualitative results reinforce the fact that MdF seems to fit to the needs of the victims-survivors throughout their trajectory. MdF supplies essential interventions recommended by the WHO to prevent VaW.24 These interventions correspond to models presented as highly efficient to improve the mental health of IPV survivors.25 On the top of that, respondents also described the MdF as a warm place where they could escape from reality, a new concept that needs to be explored in the future.

Perspectives

This study will serve as a basis for a larger comparative trial of the long-term impact of specialised care of the MdF on PTSD compared with the care in non-specialised structures: the ‘IROND-L’ study. We are planning a quantitative and a qualitative component, as well as a medico economic study. The main objective aims to assess the evolution of PTSD between the initial visit and 6 months later in women victims-survivors of violence, according to whether they are treated in structures offering a coordinated multidisciplinary approach (MdF), or in health centres or family planning. We also aim to assess the presence of sleep disorders, the quality of life, the presence of depressive and anxiety symptoms substances use, the reason for seeking care, and the women’s perception of their safety and well-being and that of their children.

In the pilot study, the mean PCL-5 score was=37.1 (SD=16.6). Therefore, a minimum of 150 women per group is required to achieve a power of 80% and 5% significance level (two sided), to detect a mean difference of 5.5 between the two groups, assuming that the SD of the differences is 17 (figure 2). Thus, 180 women per group will need to be recruited to account for a potential 35% rate of loss to follow-up. The IROND-L study will include 360 women victims of violence and will be conducted in 5 metropolitan department, and we hope it will increase generalisability of the results. However, generalisability may not be transposable as the MdF approach is new and quite unique worldwide.

Lastly, the future qualitative component will also require much greater recruitment to interview more profiles that are different and approach data saturation, which this pilot study could not achieve.

Strengths and limitations

This is the first French study assessing the prevalence of PTSD in victims-survivors of IPV in MHCs and the MdF, is the first French structure dedicated to the care of women victims of violence. The high prevalence of PTSD outlined in our study justifies the need for launching larger quantitative and qualitative researches on the mental health of the victims.

However, this study has several limitations. First, it was conducted in health facilities, and therefore, does not include women in IPV situations who do not have access to healthcare or those who face significant barriers to seeking care. Nevertheless, we do not believe that our population is biased towards more advantaged women. Indeed, even though limited, our sample embraces a wide range of situations, with 53% of women born outside of France, 37% having social security coverage reserved for those with no or low income from work or illegal immigrant status, suggesting that the facilities where the study was conducted have a broad recruitment base.

Even if we have no formal explanation for the low follow-up rate, financial difficulties have been described as an important factor in the loss to follow-up.26 As our study took place in the poorest area in France, we had anticipated, but without fair estimate, that the follow-up rate would be low. It was indeed one of our objectives to provide data to design the IROND-L study.

It is known, and we have shown10 that violent episodes occur more frequently during a break-up phase (separation, job search) and that women who are victims of violence are, therefore, logically more likely to move house or change their telephone number in order to escape their violent partner. It is, therefore, logical that these women are more difficult to monitor.

Moreover, we decided to focus on domestic violence in this pilot study and did not collect data on other stressful or traumatic events. Only the qualitative part of this study explored the duration and/or repetition of the violence and/or the duration since the possible end of the violence. This information will have to be considered and collected in the future quantitative and qualitative questionnaires of the larger IROND-L comparative study.

Finally, the health outcomes measured in this study are based solely on women’s self-reported perceptions, rather than on potentially more valid clinical observations. These limitations will be addressed in the future comparative study using a quasi-experimental design, where care pathways and the consumption of medical goods and services, will be assessed based on medical records and health insurance database.

Conclusions

Given the links between violence and women’s mental health found in this study, recommendations to encourage clinicians to inquire about their patients’ experiences of violence should be maintained. However, healthcare providers also need to be properly trained and informed to refer identified violence victims to appropriate adequate and trauma informed care. The future IROND-L study needs to assess the effect of coordinated interventions such as the ones offered at MdF on women’s mental health. This future study is of particular importance as the MDF model is to be duplicated throughout France, at the request of the French government,27 and is part of an overall French national public health policy for the care of victims of violence.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the women who agreed to participate in the study and the staff who ran the interviews with the women.

Footnotes

Twitter: @Fabienne_EK, @mbardou

NR and ND contributed equally.

Contributors: NR, MB and FEK conceived, planned and designed the study. GH, AB, LY and LF collected the questionnaires and collated the data. ND, SM and FEK performed the data management. ND, SM and FEK performed the statistical analyses. NR, ND, SM and FEK interpreted the data. NR drafted the manuscript. MB and GH ensured project and study management. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript. MB is the guarantor. Each author has confirmed compliance with the journal’s requirements for authorship.

Funding: The study was funded by crowd funding and promoted by the Dijon Bourgogne’s Teaching hospital.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request. The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to their containing information that could compromise the privacy/safety of research participants but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Consent obtained directly from patient(s).

Ethics approval

This study involves human participants and the Committee for the Protection of Persons of Ile de France 6 provided ethical approval for this study (reference number 92-19 NI Cat.3, file number 19.12.10.36712). Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . Violence against women: a ‘global health problem of epidemic proportions'. 2013. Available: https://www.who.int/news/item/20-06-2013-violence-against-women-a-global-health-problem-of-epidemic-proportions [Accessed 23 Feb 2023].

- 2.World Health Organization . Violence against women prevalence estimates, 2018: global, regional and national prevalence estimates for intimate partner violence against women and global and regional prevalence estimates for non-partner sexual violence against women. 2021.

- 3.Sardinha L, Maheu-Giroux M, Stöckl H, et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence estimates of physical or sexual, or both, intimate partner violence against women in 2018. Lancet 2022;399:803–13. 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02664-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trevillion K, Corker E, Capron LE, et al. Improving mental health service responses to domestic violence and abuse. Int Rev Psychiatry 2016;28:423–32. 10.1080/09540261.2016.1201053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scott KM, Koenen KC, King A, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder associated with sexual assault among women in the WHO world mental health surveys. Psychol Med 2018;48:155–67. 10.1017/S0033291717001593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramsay J, Carter Y, Davidson L, et al. Advocacy interventions to reduce or eliminate violence and promote the physical and psychosocial well-being of women who experience intimate partner abuse. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009:CD005043. 10.1002/14651858.CD005043.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Breiding MJ, Basile KC, Klevens J, et al. Economic insecurity and intimate partner and sexual violence Victimization. Am J Prev Med 2017;53:457–64. 10.1016/j.amepre.2017.03.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.IGAS . La Prise en charge À L’Hôpital des Femmes Victimes de violence: Éléments en vue D’Une Modélisation. Available: https://www.igas.gouv.fr/spip.php?article636 [Accessed 13 Dec 2021].

- 9.HAS . Repérage des Femmes Victimes de Violences au Sein Du couple. Haute Autorité de Santé 2020. Available: https://www.has-sante.fr/jcms/p_3104867/fr/reperage-des-femmes-victimes-de-violences-au-sein-du-couple [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roland N, Ahogbehossou Y, Hatem G, et al. Violence against women and perceived health: an observational survey of patients treated in the Multidisciplinary structure “the women’s house” and two family planning centres in the metropolitan Paris area. Health Soc Care Community 2022;30:e4041–50. 10.1111/hsc.13797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blevins CA, Weathers FW, Davis MT, et al. The Posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): development and initial psychometric evaluation. J Trauma Stress 2015;28:489–98. 10.1002/jts.22059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ashbaugh AR, Houle-Johnson S, Herbert C, et al. Psychometric validation of the English and French versions of the posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). PLoS One 2016;11:e0161645. 10.1371/journal.pone.0161645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C) An effective brief screening test for problem Drinking. Arch Intern Med 1998;158:1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McFarlane JM, Groff JY, O’Brien JA, et al. Secondary prevention of intimate partner violence: a randomized controlled trial. Nurs Res 2006;55:52–61. 10.1097/00006199-200601000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Parys A-S, Deschepper E, Roelens K, et al. The impact of a referral card-based intervention on intimate partner violence, psychosocial health, help-seeking and safety behaviour during pregnancy and postpartum: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017;17:346. 10.1186/s12884-017-1519-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moser A, Korstjens I. Series: practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 1: introduction. Eur J Gen Pract 2017;23:271–3. 10.1080/13814788.2017.1375093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization . WHO ethical and safety recommendations for researching, documenting and monitoring sexual violence in emergencies. 2007. Available: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241595681 [Accessed 28 Jul 2022].

- 18.Creswell JW, Clark VLP. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. SAGE Publications, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kyngäs H, Kääriäinen M, Elo S. The trustworthiness of content analysis. In: Kyngäs H, Mikkonen K, Kääriäinen M, eds. The application of content analysis in nursing science research. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2020: 41–8. 10.1007/978-3-030-30199-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pill N, Day A, Mildred H. Trauma responses to intimate partner violence: a review of current knowledge. Aggression and Violent Behavior 2017;34:178–84. 10.1016/j.avb.2017.01.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pemberton JV, Loeb TB. Impact of sexual and Interpersonal violence and trauma on women: trauma-informed practice and feminist theory. Journal of Feminist Family Therapy 2020;32:115–31. 10.1080/08952833.2020.1793564 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Woods SJ. Prevalence and patterns of posttraumatic stress disorder in abused and postabused women. Issues Ment Health Nurs 2000;21:309–24. 10.1080/016128400248112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dziewa A, Glowacz F. Getting out from intimate partner violence: Dynamics and processes. A qualitative analysis of female and male victims. J Fam Violence 2022;37:643–56. 10.1007/s10896-020-00245-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.World Health Organization . RESPECT women: preventing violence against women. 2019. Available: https://apps-who-int.proxy.insermbiblio.inist.fr/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/312261/WHO-RHR-18.19-eng.pdf?ua=1 [Accessed 28 Jul 2022].

- 25.Paphitis SA, Bentley A, Asher L, et al. Improving the mental health of women intimate partner violence survivors: findings from a realist review of psychosocial interventions. PLOS ONE 2022;17:e0264845. 10.1371/journal.pone.0264845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tong CYM, Koh RYV, Lee ES. A Scoping review on the factors associated with the lost to follow-up (LTFU) amongst patients with chronic disease in ambulatory care of high-income countries (HIC). BMC Health Serv Res 2023;23:883. 10.1186/s12913-023-09863-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.French Government . Présentation Du plan Interministériel pour L’Égalité Entre LES Femmes et LES Hommes 2023-2027/presentation of the Interministerial plan for equality between women and men 2023-2027. 2023. Available: https://www.gouvernement.fr/communique/presentation-du-plan-interministeriel-pour-legalite-entre-les-femmes-et-les-hommes-2023-2027

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2023-075552supp001.pdf (61.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2023-075552supp002.pdf (79.3KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request. The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to their containing information that could compromise the privacy/safety of research participants but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.