Abstract

BACKGROUND

Several studies have explored the long-term prognosis of patients with asymptomatic gallbladder stones. These reports were primarily conducted in facilities equipped with beds for addressing symptomatic cases.

AIM

To report the long-term prognosis of patients with asymptomatic gallbladder stones in clinics without bed facilities.

METHODS

We investigated the prognoses of 237 patients diagnosed with asymptomatic gallbladder stones in clinics without beds between March 2010 and October 2022. When symptoms developed, patients were transferred to hospitals where appropriate treatment was possible. We investigated the asymptomatic and survival periods during the follow-up.

RESULTS

Among the 237 patients, 214 (90.3%) remained asymptomatic, with a mean asymptomatic period of 3898.9279 ± 46.871 d (50-4111 d, 10.7 years on average). Biliary complications developed in 23 patients (9.7%), with a mean survival period of 4010.0285 ± 31.2788 d (53-4112 d, 10.9 years on average). No patient died of biliary complications.

CONCLUSION

The long-term prognosis of asymptomatic gallbladder stones in clinics without beds was favorable. When the condition became symptomatic, the patients were transferred to hospitals with beds that could address it; thus, no deaths related to biliary complications were reported. This finding suggests that follow-up care in clinics without beds is possible.

Keywords: Gallbladder stone, Acute cholangitis, Acute cholecystitis, Asymptomatic gallbladder stone, Symptomatic gallbladder stone

Core Tip: A long-term prognosis of asymptomatic gallbladder stones at a clinic without beds was favorable. Patients with asymptomatic gallbladder stones in a bedless clinic were well-cared for and had a long duration of no symptoms.

INTRODUCTION

The reported prevalence of gallbladder stones is reported to be approximately 10%-25% in the United States and Europe[1-5]. The widespread use of abdominal ultrasonography has greatly facilitated the diagnosis of gallbladder stones[6-8]. For asymptomatic patients, clinical observation is typically sufficient. However, when symptoms, such as acute cholecystitis or acute cholangitis, manifest, appropriate treatments, including drainage, surgery, and administration of antibiotics, become essential[9-11].

Guidelines for acute cholecystitis and acute cholangitis clearly specify the criteria for transferring patients to facilities capable of providing appropriate treatment[12]. Diagnostic criteria have also been established for acute pancreatitis triggered by gallbladder stones[13]. Once patients are diagnosed with acute pancreatitis, it becomes imperative to transfer them to facilities with inpatient services, as untreated acute pancreatitis may lead to organ failure or life-threatening infections. Therefore, understanding the timing of transferring patients to facilities with inpatient services when gallbladder stones become symptomatic is crucial.

Although it is important for the attending physician to be aware of potential symptoms, asymptomatic gallbladder stones are frequently managed through periodic monitoring in clinics. To date, several reports have provided insights into the long-term prognosis of asymptomatic gallbladder stones mainly from facilities equipped to accommodate inpatients[14-19]. To the best of our knowledge, no studies have been reported from clinics that lack inpatient facilities that have observed clinical courses of asymptomatic gallbladder stones for more than a decade. Therefore, in this study, we explored the long-term prognosis of asymptomatic gallbladder stones at a clinic without beds.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Between March 2010 and October 2022, we followed up 237 patients diagnosed with gallbladder stones among 3268 cases of abdominal ultrasonography performed during screening at Sakai Clinic, a bedless clinic. Patients with gallbladder stones visited the hospital once a month for evaluation of their condition. At the time of consultation, all 237 patients had asymptomatic gallbladder stones, and none of them had a history of seizures. Patients’ demographic details are summarized in Table 1. The study included 123 males and 114 females, with a mean age of 47.675 ± 15.625 (range: 20-78) years. The mean number of gallbladder stones was 2.318 ± 3.500 (range: 1-20), and the mean stone diameter was 7.343 ± 4.298 (range: 1-22) mm. Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) was administered based on patient’s request after they were informed about its pharmacological effects. Patients who took UDCA ≥ 300 mg daily for 6 mo or more were categorized into the active treatment arm (UDCA group), and this arm included 68 patients. Comorbidity included hypertension in 125 (52.7%) patients, hyperlipidemia in 119 (50.2%) patients, diabetes mellitus in 110 (46.4%) patients, cerebrovascular disease in 42 (17.7%) patients, chronic respiratory disease in 37 (15.6%) patients, heart disease in 28 (11.8%) patients, chronic liver disease in 35 (14.8%) patients, chronic renal disease in 42 (17.7%) patients, and malignant disease in 10 (4.2%) patients. Patients diagnosed with gallbladder stones underwent abdominal ultrasonography once every 6-12 mo. Blood samples were collected at least once every 6 mo or once a month depending on the comorbidity. Abdominal ultrasonography was routinely performed by changing the posture to depict the location of gallbladder and common bile duct. In cases where the visualization of the common bile duct was difficult with abdominal ultrasonography, abdominal computed tomography (CT) was performed. Abdominal ultrasonography was performed using one of the two models (TOSHIBA SSA-250A, Japan or Canon Xario 100, Japan). CT was performed using a 16-slice MDCT scanner (TOSHIBA Activion16, Japan), with a detector collimation of 1 mm × 16 mm, table feed of 24 mm per rotation, rotation time of 1 s, tube current of 200 effective mAs, and tube voltage of 120 kV. Axial images were reconstructed by 5 mm without overlap and coronal images by 3 mm without overlap. No contrast medium was used for the assessments.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

|

Characteristic

|

Value

|

| Number of patients | 237 |

| Male | 123 |

| Female | 114 |

| Age in yr | 47.675 ± 15.625 (20-78) |

| Gallbladder stone | |

| Number of stones | 2.318 ± 3.500 (1-20) |

| Size in mm | 7.343 ± 4.298 (1-22) |

| UDCA | 68 |

| Hypertension | 125 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 119 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 110 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 42 |

| Chronic respiratory disease | 37 |

| Cardiac disease | 28 |

| Chronic liver disease | 35 |

| Chronic renal disease | 42 |

| Malignant disease | 10 |

UDCA: Ursodeoxycholic acid.

Biliary complications, such as acute cholecystitis, acute cholangitis, obstructive jaundice, and gallstone pancreatitis, were considered symptomatic. Abdominal pain during the time-course observation caused by reasons other than gallbladder stones was not considered symptomatic. Emergency abdominal ultrasonography was performed when patients developed abdominal pain, fever, or jaundice during clinic visits. If additional tests were necessary, they were conducted at the discretion of physicians. When acute cholecystitis, acute cholangitis, or gallstone pancreatitis was suspected, patients were promptly transferred to hospitals equipped to provide appropriate care, following the Tokyo Guidelines (for acute cholecystitis and acute cholangitis)[20-25] and the revised Atlanta classification (for acute pancreatitis) that existed at the time of onset[13].

To assess the long-term prognosis, we directly communicated with the patient and transfer hospitals, in addition to utilizing data from the outpatient clinic. The study was conducted at this clinic after obtaining consent from all patients regarding the use of the data. We obtained approval from the institutional review board of Chiba Prefectural Sawara Hospital (IRB number 4-12). The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Statistical analysis

For statistical analysis of categorical variables, the Pearson χ2 test with Yates correction and Fisher’s exact test were used, as deemed appropriate. Differences were considered statistically significant at P values < 0.05. Asymptomatic and survival periods were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Data were analyzed using Excel software (Version 2020).

RESULTS

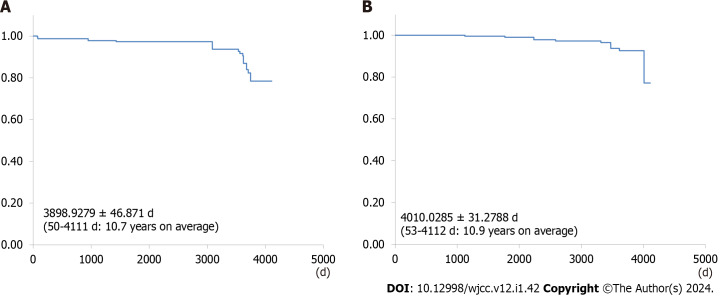

A total of 214 (90.3 %) patients remained asymptomatic during the observation period, lasting for an average duration of 3898.9279 ± 46.871 d (50-4111 d, 10.7 years on average) (Figure 1A). Among them, 23 (9.7%) patients experienced biliary complications, including acute cholecystitis in 14 (5.9%) patients, acute cholangitis in 5 (2.1%) patients, obstructive jaundice in 2 (0.8%) patients, and gallstone pancreatitis in 2 (0.8%) patients (Table 2). Comparing the group with no biliary complications during long-term follow-up to the group with biliary complications revealed significantly higher rates of biliary complications in the group with multiple gallbladder stones, those with stones 10 mm or less in diameter, and the non-UDCA group (Table 3).

Figure 1.

Long-term prognosis of asymptomatic gallbladder stones. A: Asymptomatic period; B: Survival period.

Table 2.

Biliary complications noted during the observation period

|

Biliary complication

|

Value

|

| Biliary event | 23 |

| Acute cholecystitis | 14 |

| Acute cholangitis | 5 |

| Obstructive jaundice | 2 |

| Gallstone pancreatitis | 2 |

Table 3.

Comparison of the groups with and without biliary complications

|

Characteristic

|

No symptom, n = 214

|

Biliary event, n = 23

|

P value

|

| Male | 108 | 15 | 0.1951 |

| Female | 106 | 8 | 0.1951 |

| Gallstone | |||

| Number ≤ 2 | 3 | 20 | < 0.0010 |

| Diameter < 10 mm | 3 | 20 | < 0.0010 |

| UDCA | 66 | 2 | 0.0277 |

| Hypertension | 115 | 10 | 0.6653 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 108 | 11 | 0.8293 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 102 | 8 | 0.5078 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 36 | 6 | 0.1111 |

| Chronic respiratory disease | 33 | 4 | 0.5384 |

| Cardiac disease | 26 | 2 | 1.0000 |

| Chronic liver disease | 32 | 3 | 1.0000 |

| Chronic renal disease | 36 | 6 | 0.1111 |

| Malignant disease | 9 | 1 | 1.0000 |

UDCA: Ursodeoxycholic acid.

The mean survival period was 4010.0285 ± 31.2788 d (53-4112 d, 10.9 years on average) (Figure 1B). Eleven (4.6%) deaths occurred during the observation period, with the causes being lung cancer in 4 (1.7%) patients, cerebral infarction in 3 (1.3%) patients, acute myocardial infarction in 2 (0.8%) patients, gastric cancer in 1 (0.4%) patient, and colorectal cancer in 1 (0.4%) patient (Table 4). Notably, no deaths due to biliary complications were noted during the observation period for asymptomatic gallstones.

Table 4.

Causes of deaths during the observation period

|

Causes of deaths

|

n

|

| Total number | 11 |

| Lung cancer | 4 |

| Cerebral infarction | 3 |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 2 |

| Gastric cancer | 1 |

| Colorectal cancer | 1 |

Prognoses were ascertained through outpatient visits alone in 211 (89%) patients and by inquiring hospitals to which patients were transferred in 13 (5.5%) patients. For the remaining 13 (5.5%) patients, the prognoses were determined through direct telephone conversation with them. Prognoses were determined for all 237 (100%) patients. Notably, 22 (9.3%) patients underwent abdominal CT due to the difficulty in visualizing the common bile duct using ultrasonography.

All 23 patients with biliary complications were transferred from the clinic to hospitals. All clinical and hospital diagnoses were consistent. Out of the 23 patients with biliary complications, 20 underwent cholecystectomies. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy and open cholecystectomy were performed in 18 patients and 2 patients, respectively. However, one of the patients, a 78-year-old man with lung cancer, who developed acute cholecystitis did not undergo surgery because his condition improved with conservative antibiotic therapy. When he provided informed consent regarding his prognosis, he did not wish to undergo further surgery. Instead, he was placed under a time-course observation, and no recurrence of acute cholecystitis was observed for 18 mo until he succumbed to cancer. Two other women who did not undergo surgery developed acute cholangitis, and their symptoms improved after endoscopic transpapillary removal of the common bile duct stones. Both the patients were 85 years old with multiple comorbidities. They were considered unfit for surgery; therefore, they were closely monitored without surgical intervention. In both cases, neither patient had experienced any seizures for over 2 years.

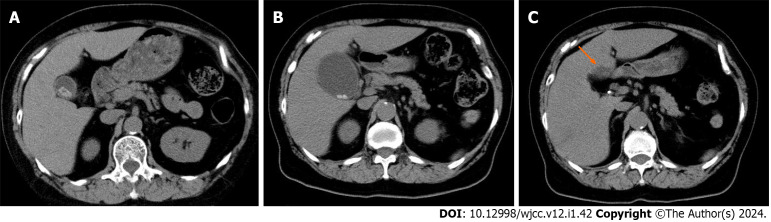

Postoperative biloma was noted in 1 patient (5%) who underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis due to surgery-related complications; however, the condition improved with conservative therapy (Figure 2). No accidental surgery-related symptoms were observed. In 1 case of acute cholecystitis, histopathological examination following laparoscopic cholecystectomy revealed carcinoma in situ. This case initially presented with numerous small stones, as observed on abdominal ultrasonography, which made evaluation of the gallbladder wall challenging. The patient has been followed up for 12 mo postoperatively, but no recurrence was noted. Gallbladder cancer was observed in only this patient (0.004%) during the observation period.

Figure 2.

A 68-year-old female. A: Computed tomography revealed gallbladder stones; B: Onset of acute cholecystitis 1215 d after the diagnosis of gallbladder stones; C: Biloma was noted on the computed tomography scan after laparoscopic cholecystectomy (arrow).

DISCUSSION

Several reports on the natural history of asymptomatic gallbladder stones have been published to date, primarily originating from institutions with inpatient facilities and research institutions[14-19]. Our study focused on reports from clinics without beds, but no major differences were observed compared to reports from clinics with beds and research institutions. In symptomatic patients, the diameter of stones was smaller and the number of stones was significantly higher than those of asymptomatic patients. Gallbladder stones with smaller diameters are more likely to affect the cystic duct than those with larger diameters. Similarly, gallbladder stones with smaller diameters are more likely to fall into the common bile duct than those with larger diameters. As the number of gallbladder stones increases, the probability of the stones impacting the cystic duct or falling into the common bile duct is also expected to increase. A single large gallbladder stone is unlikely to fall into the common bile duct, which may explain our findings.

In addition, the UDCA group was significantly less likely to become symptomatic than the non-UDCA group. UDCA, known for promoting bile outflow, may suppress the increase in gallbladder stones by promoting bile outflow. Therefore, it may prevent gallbladder stones from becoming impacted in the cystic duct or falling into the common bile duct, which may reduce the likelihood of symptoms. Previous studies have reported that long-term administration of UDCA has a prophylactic effect against the development of symptomatic gallbladder stones[26]. Some reports have suggested that short-term UDCA administration during the waiting period for cholecystectomy does not prevent the condition from becoming symptomatic[27]. Therefore, it is unlikely that UDCA has little preventive effect against symptomatic gallbladder stones when administered for a brief period.

In this study, 1 case of gallbladder cancer was identified, demonstrating carcinoma in situ upon pathological examination of resected specimen following laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis. Abdominal ultrasonography revealed a number of small stones, posing challenges in the evaluation of the gallbladder. Preoperative examination at the hospital to which the patient was transferred did not detect the presence of gallbladder cancer. A meta-analysis of three cohort studies and seven case-control studies revealed that gallbladder stones present the strongest risk factor for gallbladder cancer, with a relative risk of 4.9[28]. Meanwhile, a cohort study spanning approximately 11 years, including more than 110000 patients, reported a hazard ratio of 1.07 for gallbladder stones and a history of cholecystitis in relation to carcinogenesis, showing a negative association between gallbladder stones and the development of gallbladder cancer[29]. The incidence of gallbladder cancer in patients with gallbladder stones is as low as 0.01%-0.02% annually. Observational studies over 5 years have also shown an extremely limited incidence of approximately 0.3%[30]. Although the causal relationship between gallbladder stones and gallbladder cancer is well known, concrete evidence directly linking gallbladder stones to the development of gallbladder cancer is currently lacking. In this study, the incidence of gallbladder cancer was extremely low (0.004%). Preventive cholecystectomy can help obviate symptoms or hedge the risk of gallbladder cancer.

Cholecystectomy may cause life-threatening complications, such as vascular and bile duct injuries, albeit these are extremely rare[10]. In our study, biloma was noted after the procedure, although it was not a serious complication. Notably, these complications occur at a certain rate after cholecystectomy. Although no prospective studies have been conducted concerning cholecystectomy vs time-course observation, the therapeutic intervention for asymptomatic cases offers little benefits. Cholecystectomy should be considered only when its benefits outweigh its risks. In cases where evaluation of the gallbladder wall is difficult because of chronic cholecystitis or gallstones, surgery should be considered even in the absence of symptoms.

The long-term prognosis of asymptomatic gallstones in clinics without beds was favorable, with no deaths due to biliary complications when medical care was provided according to the criteria for diagnosis and transportation. The follow-up of these patients at the outpatient clinic was satisfactory. However, this favorable long-term prognosis is only for asymptomatic patients and not for symptomatic gallbladder stones. Symptomatic gallstones have a higher incidence of biliary complications than asymptomatic gallstones[16-19]. We cannot rule out the possibility that different results could be obtained in a long-term prognostic study. Notably, our study was retrospective and conducted at a single institution. A prospective study with a larger number of bedless clinics is necessary in the future to further investigate this matter.

CONCLUSION

The long-term prognosis of asymptomatic gallbladder stones in clinics without beds is favorable. When the condition became symptomatic, the patients were transported to hospitals equipped with beds to manage the condition, contributing to the absence of reported deaths related to biliary complications. The follow-up of asymptomatic gallbladder stones in a clinic without inpatient beds was deemed effective.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Several reports on a long-term prognosis of asymptomatic gallbladder stones that have been available to date are mainly from facilities that can accommodate inpatients. As far as we know, there has been no report to date from a clinic without beds that observed clinical courses of more than a decade.

Research motivation

There is currently no study of the long-term prognosis of asymptomatic gallbladder stones from a clinic without beds.

Research objectives

To determine the long-term prognosis of asymptomatic gallbladder stones in a clinic without beds.

Research methods

We followed up 237 cases diagnosed with asymptomatic gallbladder stones.

Research results

Those patients whose condition was asymptomatic during the observation period accounted for 214 cases (90.3%). The asymptomatic period was 3898.9279 ± 46.871 d (50-4111 d, 10.7 years on average).

Research conclusions

When the condition turned symptomatic, patients were transported to hospitals with beds that could address the condition, and no deaths related to biliary complications was reported. Asymptomatic gallbladder stones were considered to be well followed in a bedless clinic.

Research perspectives

Our study was a retrospective study in a single institution. A prospective study in a large number of bedless clinics is considered necessary in the future.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: A study at this clinic was conducted after obtaining approval from all patients about the use of data. We requested the Institutional Review Board at Chiba Prefectural Sawara Hospital to review data and obtained their approval (IRB No. 4-12).

Informed consent statement: In order to know the long-term prognosis, we confirmed the prognosis by directly calling the patient and the transportation hospitals in addition to the information at the outpatient clinic.

Conflict-of-interest statement: All authors declare having no conflicts of interest.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Peer-review started: September 3, 2023

First decision: October 24, 2023

Article in press: December 18, 2023

Specialty type: Gastroenterology & hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Japan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Fan Y, China S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Yan JP

Contributor Information

Yuji Sakai, Department of Gastroenterology, Sakai Clinic, Kimistu 299-1162, Japan; Department of Gastroenterology, Graduate School of Medicine, Chiba University, Chiba 260-8677, Japan. sakai4754@yahoo.co.jp.

Toshio Tsuyuguchi, Department of Gastroenterology, Chiba Prefectural Sawara Hospital, Chiba Prefectural Sawara Hospital, Sawara 287-0003, Japan.

Hiroshi Ohyama, Department of Gastroenterology, Graduate School of Medicine, Chiba University, Chiba 260-8677, Japan.

Junichiro Kumagai, Department of Gastroenterology, Kimitsu Central Hospital, Kisarazu 292-8535, Japan.

Takashi Kaiho, Department of Surgery, Kimitsu Central Hospital, Kisarazu 292-8535, Japan.

Masayuki Ohtsuka, Department of General Surgery, Graduate School of Medicine, Chiba University, Chiba 260-8677, Japan.

Naoya Kato, Department of Gastroenterology, Graduate School of Medicine, Chiba University, Chiba 260-8677, Japan.

Tadao Sakai, Department of Gastroenterology, Sakai Clinic, Kimistu 299-1162, Japan.

Data sharing statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Everhart JE, Khare M, Hill M, Maurer KR. Prevalence and ethnic differences in gallbladder disease in the United States. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:632–639. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70456-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glambek I, Kvaale G, Arnesjö B, Søreide O. Prevalence of gallstones in a Norwegian population. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1987;22:1089–1094. doi: 10.3109/00365528708991963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muhrbeck O, Ahlberg J. Prevalence of gallstone disease in a Swedish population. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1995;30:1125–1128. doi: 10.3109/00365529509101618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shaffer EA. Gallstone disease: Epidemiology of gallbladder stone disease. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;20:981–996. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Portincasa P, Moschetta A, Palasciano G. Cholesterol gallstone disease. Lancet. 2006;368:230–239. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69044-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gustafsson C, McNicholas A, Sondén A, Törngren S, Järnbert-Pettersson H, Lindelius A. Accuracy of Surgeon-Performed Ultrasound in Detecting Gallstones: A Validation Study. World J Surg. 2016;40:1688–1694. doi: 10.1007/s00268-016-3468-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carroll PJ, Gibson D, El-Faedy O, Dunne C, Coffey C, Hannigan A, Walsh SR. Surgeon-performed ultrasound at the bedside for the detection of appendicitis and gallstones: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Surg. 2013;205:102–108. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2012.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fang R, Pilcher JA, Putnam AT, Smith T, Smith DL. Accuracy of surgeon-performed gallbladder ultrasound. Am J Surg. 1999;178:475–479. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(99)00225-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sakai Y, Tsuyuguchi T, Kato K, Sugiyama H, Nishikawa T, Takahashi M, Yokosuka O. Clinical usefulness of doripenem (DRPM), a carbapenem antimicrobial drug, for the treatment of patients with acute cholangitis: retrospective study. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2013;51:19–25. doi: 10.5414/CP201786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gallaher JR, Charles A. Acute Cholecystitis: A Review. JAMA. 2022;327:965–975. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.2350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ito K, Fujita N, Noda Y, Kobayashi G, Kimura K, Sugawara T, Horaguchi J. Percutaneous cholecystostomy vs gallbladder aspiration for acute cholecystitis: a prospective randomized controlled trial. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;183:193–196. doi: 10.2214/ajr.183.1.1830193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miura F, Okamoto K, Takada T, Strasberg SM, Asbun HJ, Pitt HA, Gomi H, Solomkin JS, Schlossberg D, Han HS, Kim MH, Hwang TL, Chen MF, Huang WS, Kiriyama S, Itoi T, Garden OJ, Liau KH, Horiguchi A, Liu KH, Su CH, Gouma DJ, Belli G, Dervenis C, Jagannath P, Chan ACW, Lau WY, Endo I, Suzuki K, Yoon YS, de Santibañes E, Giménez ME, Jonas E, Singh H, Honda G, Asai K, Mori Y, Wada K, Higuchi R, Watanabe M, Rikiyama T, Sata N, Kano N, Umezawa A, Mukai S, Tokumura H, Hata J, Kozaka K, Iwashita Y, Hibi T, Yokoe M, Kimura T, Kitano S, Inomata M, Hirata K, Sumiyama Y, Inui K, Yamamoto M. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: initial management of acute biliary infection and flowchart for acute cholangitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018;25:31–40. doi: 10.1002/jhbp.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, Gooszen HG, Johnson CD, Sarr MG, Tsiotos GG, Vege SS Acute Pancreatitis Classification Working Group. Classification of acute pancreatitis--2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut. 2013;62:102–111. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gracie WA, Ransohoff DF. The natural history of silent gallstones: the innocent gallstone is not a myth. N Engl J Med. 1982;307:798–800. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198209233071305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morris-Stiff G, Sarvepalli S, Hu B, Gupta N, Lal P, Burke CA, Garber A, McMichael J, Rizk MK, Vargo JJ, Ibrahim M, Rothberg MB. The Natural History of Asymptomatic Gallstones: A Longitudinal Study and Prediction Model. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;21:319–327.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Festi D, Reggiani ML, Attili AF, Loria P, Pazzi P, Scaioli E, Capodicasa S, Romano F, Roda E, Colecchia A. Natural history of gallstone disease: Expectant management or active treatment? Results from a population-based cohort study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:719–724. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.06146.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McSherry CK, Ferstenberg H, Calhoun WF, Lahman E, Virshup M. The natural history of diagnosed gallstone disease in symptomatic and asymptomatic patients. Ann Surg. 1985;202:59–63. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198507000-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Friedman GD, Raviola CA, Fireman B. Prognosis of gallstones with mild or no symptoms: 25 years of follow-up in a health maintenance organization. J Clin Epidemiol. 1989;42:127–136. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(89)90086-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Persson GE. Expectant management of patients with gallbladder stones diagnosed at planned investigation. A prospective 5- to 7-year follow-up study of 153 patients. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1996;31:191–199. doi: 10.3109/00365529609031985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hirota M, Takada T, Kawarada Y, Nimura Y, Miura F, Hirata K, Mayumi T, Yoshida M, Strasberg S, Pitt H, Gadacz TR, de Santibanes E, Gouma DJ, Solomkin JS, Belghiti J, Neuhaus H, Büchler MW, Fan ST, Ker CG, Padbury RT, Liau KH, Hilvano SC, Belli G, Windsor JA, Dervenis C. Diagnostic criteria and severity assessment of acute cholecystitis: Tokyo Guidelines. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2007;14:78–82. doi: 10.1007/s00534-006-1159-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wada K, Takada T, Kawarada Y, Nimura Y, Miura F, Yoshida M, Mayumi T, Strasberg S, Pitt HA, Gadacz TR, Büchler MW, Belghiti J, de Santibanes E, Gouma DJ, Neuhaus H, Dervenis C, Fan ST, Chen MF, Ker CG, Bornman PC, Hilvano SC, Kim SW, Liau KH, Kim MH. Diagnostic criteria and severity assessment of acute cholangitis: Tokyo Guidelines. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2007;14:52–58. doi: 10.1007/s00534-006-1156-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yokoe M, Takada T, Strasberg SM, Solomkin JS, Mayumi T, Gomi H, Pitt HA, Gouma DJ, Garden OJ, Büchler MW, Kiriyama S, Kimura Y, Tsuyuguchi T, Itoi T, Yoshida M, Miura F, Yamashita Y, Okamoto K, Gabata T, Hata J, Higuchi R, Windsor JA, Bornman PC, Fan ST, Singh H, de Santibanes E, Kusachi S, Murata A, Chen XP, Jagannath P, Lee S, Padbury R, Chen MF Tokyo Guidelines Revision Committee. New diagnostic criteria and severity assessment of acute cholecystitis in revised Tokyo Guidelines. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2012;19:578–585. doi: 10.1007/s00534-012-0548-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kiriyama S, Takada T, Strasberg SM, Solomkin JS, Mayumi T, Pitt HA, Gouma DJ, Garden OJ, Büchler MW, Yokoe M, Kimura Y, Tsuyuguchi T, Itoi T, Yoshida M, Miura F, Yamashita Y, Okamoto K, Gabata T, Hata J, Higuchi R, Windsor JA, Bornman PC, Fan ST, Singh H, de Santibanes E, Gomi H, Kusachi S, Murata A, Chen XP, Jagannath P, Lee S, Padbury R, Chen MF Tokyo Guidelines Revision Committee. New diagnostic criteria and severity assessment of acute cholangitis in revised Tokyo Guidelines. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2012;19:548–556. doi: 10.1007/s00534-012-0537-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yokoe M, Hata J, Takada T, Strasberg SM, Asbun HJ, Wakabayashi G, Kozaka K, Endo I, Deziel DJ, Miura F, Okamoto K, Hwang TL, Huang WS, Ker CG, Chen MF, Han HS, Yoon YS, Choi IS, Yoon DS, Noguchi Y, Shikata S, Ukai T, Higuchi R, Gabata T, Mori Y, Iwashita Y, Hibi T, Jagannath P, Jonas E, Liau KH, Dervenis C, Gouma DJ, Cherqui D, Belli G, Garden OJ, Giménez ME, de Santibañes E, Suzuki K, Umezawa A, Supe AN, Pitt HA, Singh H, Chan ACW, Lau WY, Teoh AYB, Honda G, Sugioka A, Asai K, Gomi H, Itoi T, Kiriyama S, Yoshida M, Mayumi T, Matsumura N, Tokumura H, Kitano S, Hirata K, Inui K, Sumiyama Y, Yamamoto M. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: diagnostic criteria and severity grading of acute cholecystitis (with videos) J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018;25:41–54. doi: 10.1002/jhbp.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kiriyama S, Kozaka K, Takada T, Strasberg SM, Pitt HA, Gabata T, Hata J, Liau KH, Miura F, Horiguchi A, Liu KH, Su CH, Wada K, Jagannath P, Itoi T, Gouma DJ, Mori Y, Mukai S, Giménez ME, Huang WS, Kim MH, Okamoto K, Belli G, Dervenis C, Chan ACW, Lau WY, Endo I, Gomi H, Yoshida M, Mayumi T, Baron TH, de Santibañes E, Teoh AYB, Hwang TL, Ker CG, Chen MF, Han HS, Yoon YS, Choi IS, Yoon DS, Higuchi R, Kitano S, Inomata M, Deziel DJ, Jonas E, Hirata K, Sumiyama Y, Inui K, Yamamoto M. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: diagnostic criteria and severity grading of acute cholangitis (with videos) J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018;25:17–30. doi: 10.1002/jhbp.512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tomida S, Abei M, Yamaguchi T, Matsuzaki Y, Shoda J, Tanaka N, Osuga T. Long-term ursodeoxycholic acid therapy is associated with reduced risk of biliary pain and acute cholecystitis in patients with gallbladder stones: a cohort analysis. Hepatology. 1999;30:6–13. doi: 10.1002/hep.510300108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Venneman NG, Besselink MG, Keulemans YC, Vanberge-Henegouwen GP, Boermeester MA, Broeders IA, Go PM, van Erpecum KJ. Ursodeoxycholic acid exerts no beneficial effect in patients with symptomatic gallstones awaiting cholecystectomy. Hepatology. 2006;43:1276–1283. doi: 10.1002/hep.21182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Randi G, Franceschi S, La Vecchia C. Gallbladder cancer worldwide: geographical distribution and risk factors. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:1591–1602. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yagyu K, Lin Y, Obata Y, Kikuchi S, Ishibashi T, Kurosawa M, Inaba Y, Tamakoshi A JACC Study Group. Bowel movement frequency, medical history and the risk of gallbladder cancer death: a cohort study in Japan. Cancer Sci. 2004;95:674–678. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2004.tb03328.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miyazaki M, Takada T, Miyakawa S, Tsukada K, Nagino M, Kondo S, Furuse J, Saito H, Tsuyuguchi T, Chijiiwa K, Kimura F, Yoshitomi H, Nozawa S, Yoshida M, Wada K, Amano H, Miura F Japanese Association of Biliary Surgery; Japanese Society of Hepato-Pancreatic Surgery; Japan Society of Clinical Oncology. Risk factors for biliary tract and ampullary carcinomas and prophylactic surgery for these factors. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2008;15:15–24. doi: 10.1007/s00534-007-1276-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.