Abstract

BACKGROUND

Since its description in 1790 by Hunter, the nasogastric tube (NGT) is commonly used in any healthcare setting for alleviating gastrointestinal symptoms or enteral feeding. However, the risks associated with its placement are often underestimated. Upper airway obstruction with a NGT is an uncommon but potentially life-threatening complication. NGT syndrome is characterized by the presence of an NGT, throat pain and vocal cord (VC) paralysis, usually bilateral. It is potentially life–threatening, and early diagnosis is the key to the prevention of fatal upper airway obstruction. However, fewer cases may have been reported than might have occurred, primarily due to the clinicians' unawareness. The lack of specific signs and symptoms and the inability to prove temporal relation with NGT insertion has made diagnosing the syndrome quite challenging.

AIM

To review and collate the data from the published case reports and case series to understand the possible risk factors, early warning signs and symptoms for timely detection to prevent the manifestation of the complete syndrome with life-threatening airway obstruction.

METHODS

We conducted a systematic search for this meta-summary from the database of PubMed, EMBASE, Reference Citation Analysis (https://www.referencecitationanalysis.com/) and Google scholar, from all the past studies till August 2023. The search terms included major MESH terms "Nasogastric tube", "Intubation, Gastrointestinal", "Vocal Cord Paralysis", and “Syndrome”. All the case reports and case series were evaluated, and the data were extracted for patient demographics, clinical symptomatology, diagnostic and therapeutic interventions, clinical course and outcomes. A datasheet for evaluation was further prepared.

RESULTS

Twenty-seven cases, from five case series and 13 case reports, of NGT syndrome were retrieved from our search. There was male predominance (17, 62.96%), and age at presentation ranged from 28 to 86 years. Ten patients had diabetes mellitus (37.04%), and nine were hypertensive (33.33%). Only three (11.11%) patients were reported to be immunocompromised. The median time for developing symptoms after NGT insertion was 14.5 d (interquartile range 6.25-33.75 d). The most commonly reported reason for NGT insertion was acute stroke (10, 37.01%) and the most commonly reported symptoms were stridor or wheezing 17 (62.96%). In 77.78% of cases, bilateral VC were affected. The only treatment instituted in most patients (77.78%) was removing the NG tube. Most patients (62.96%) required tracheostomy for airway protection. But 8 of the 23 survivors recovered within five weeks and could be decannulated. Three patients were reported to have died.

CONCLUSION

NGT syndrome is an uncommon clinical complication of a very common clinical procedure. However, an under-reporting is possible because of misdiagnosis or lack of awareness among clinicians. Patients in early stages and with mild symptoms may be missed. Further, high variability in the presentation timing after NGT insertion makes diagnosis challenging. Early diagnosis and prompt removal of NGT may suffice in most patients, but a significant proportion of patients presenting with respiratory compromise may require tracheostomy for airway protection.

Keywords: Nasogastric tube, Nasogastric tube syndrome, Ryle’s tube, Sofferman syndrome, Vocal cord paralysis

Core Tip: Nasogastric tube (NGT) insertion is a commonly employed procedure in hospitalised patients. Although it is considered a minor and safe procedure, complications may occur due to its invasive nature. Immediate complications while NGT insertion may be easily recognised, but long-term complications may be missed and are rarely reported. Most of the complications are minor and can be rapidly detected, but rarely, life-threatening complications like NGT syndrome have also been reported. NGT syndrome has been described decades ago, but till now, very few adult cases have been reported in the literature. Timely recognition and a simple intervention of NGT removal may be life-saving, and most patients may show complete recovery. However, a significant proportion of these patients may require tracheostomy for airway protection until the vocal cord palsy recovers.

INTRODUCTION

Nasogastric tube (NGT) insertion is a common procedure for hospitalised patients. Although NGT insertion is considered a simple procedure, it may lead to complications because of its invasive nature. Elderly, critically ill and those with underlying comorbidities may be prone to develop these complications, but these are the patients who may also benefit the most from NGT insertion. The commonly reported complications of NGT include malposition, knotting or coiling of the tube, and local trauma or bleeding[1,2]. Most of these complications occur during NGT insertion and are generally mild and easily recognised. Severe complications like oesophageal rupture have also been reported. In patients with long-standing NGT tubes, ulceration or necrosis of nasal alar, epistaxis, congestion, rhinosinusitis, and acute otitis media have also been reported[2-4]. Other complications associated with NGT include impaired lower oesophageal sphincter function, leading to increased gastroesophageal reflux (GER) and aspiration pneumonitis[2]. However, certain long-term complications associated with NGT, like the NGT syndrome, may be challenging to recognise and rarely reported (Tables 1 and 2)[5-22].

Table 1.

Base-line parameters of patients developing “nasogastric tube syndrome”

|

Case number

|

Author

|

Year of publication

|

Country of origin

|

Number of cases

|

Age

|

Sex

|

Comorbidities

|

Immunocompromised

|

Indication for NGT insertion

|

| 1 | Sofferman and Hubbell[5] | 1981 | United States | 4 | 60 | Female | Cecal cancer | None | Perioperative |

| 2 | Sofferman and Hubbell[5] | 1981 | United States | 4 | 74 | Male | None | None | CVA |

| 3 | Sofferman and Hubbell[5] | 1981 | United States | 4 | 34 | Male | None | None | Severe TBI |

| 4 | Sofferman and Hubbell[5] | 1981 | United States | 4 | 75 | Female | Osler-Weber-Rendu disease, Anemia | None | Post-operative |

| 5 | Sofferman et al[6] | 1990 | United States | 4 | 28 | Male | DM, HTN, CKD | Yes (post-renal transplantation) | Perioperative period |

| 6 | Sofferman et al[6] | 1990 | United States | 4 | 42 | Male | DM, HTN, CKD, CAD | Yes (post-renal transplantation) | Perioperative period |

| 7 | Sofferman et al[6] | 1990 | United States | 4 | 36 | Male | DM, CKD | No | AMS |

| 8 | Sofferman et al[6] | 1990 | United States | 4 | 45 | Female | DM, CKD | Yes (post-renal transplantation) | Acute pancreatitis |

| 9 | Apostolakis et al[7] | 2001 | United States | 2 | 77 | Male | None | No | Toxic megacolon |

| 10 | Apostolakis et al[7] | 2001 | United States | 2 | 73 | Male | DM, HTN, COPD | No | GI bleed |

| 11 | To et al[8] | 2001 | Hong Kong | 1 | 63 | Male | NA | NA | Perioperative period |

| 12 | Nehru et al[9] | 2003 | Kuwait | 1 | 60 | Male | DM, HTN | No | Acute stroke |

| 13 | Sanaka et al[10] | 2004 | Japan | 1 | 85 | Male | HTN | No | Gastrointestinal obstruction |

| 14 | Isozaki et al[11] | 2005 | Japan | 2 | 73 | Male | NA | NA | Dementia |

| 15 | Isozaki et al[11] | 2005 | Japan | 2 | 77 | Male | NA | NA | Acute stroke |

| 16 | Marcus et al[12] | 2006 | Israel | 1 | 72 | Male | None | No | Traumatic brain injury |

| 17 | Vielva del Campo et al[13] | 2010 | Spain | 1 | 70 | Female | DM, Parkinsonism | No | Acute stroke |

| 18 | Kim et al[14] | 2015 | Korea | 1 | 86 | Female | DM, HTN, Parkinsonism | NA | Severe pneumonia with septic shock |

| 19 | Sano et al[15] | 2016 | Japan | 1 | 76 | Male | No | No | GI obstruction |

| 20 | Perera[16] | 2018 | Sri Lanka | 1 | 76 | Female | NA | NA | Acute stroke |

| 21 | Kanbayashi et al[17] | 2021 | Japan | 1 | 77 | Male | HTN, AF | No | Acute stroke |

| 22 | Yildiz et al[18] | 2021 | Türkiye | 1 | 73 | Male | NA | NA | Perioperative |

| 23 | Taira et al[19] | 2022 | Japan | 1 | 78 | Male | No | NA | AMS |

| 24 | Cui et al[20] | 2023 | China | 1 | 65 | Female | HTN, Parkinsonism | No | Cervical cord injury |

| 25 | Nihira et al[21] | 2023 | Japan | 1 | 86 | Female | None | No | Acute stroke |

| 26 | Paul et al[22] | 2023 | Qatar | 2 | 78 | Female | DM, HTN | No | Perioperative |

| 27 | Paul et al[22] | 2023 | Qatar | 2 | 79 | Female | DM, CAD | No | AMS |

NGT: Nasogastric syndrome; DM: Diabetes mellitus; HTN: Hypertension; CKD: Chronic kidney disease; CAD: Coronary artery disease; AMS: Altered mental status; NA: Not available; COPD: Chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases; CVA: Cerebrovascular accident; TBI: Traumatic brain injury; GI: Gastrointestinal; AF: Atrial fibrillation.

Table 2.

Clinical course of patients with nasogastric syndrome

| Case number | Presenting symptoms | Type of feed NGT | Days after which symptoms developed | Side of vocal cords involved | Laryngoscopy | Biopsy | Culture | Therapeutic interventions | Tracheostomy | Outcome | Sequalae |

| 1 | Voice change, throat pain | NG | 3 | B/L | Vocal cord edema, post cricoid abcess | None | None | NG removal, steroids, antibiotics | Yes | Alive | Recovered in 7 d and discharged |

| 2 | Sore throat, stridor | NG | 8 | B/L | Vocal cod edema, arytenoid edema, post cricoid ulceration | None | None | NG removal | Yes | Alive | Recovery in 14 d |

| 3 | Throat discomfort, aspiration, | NG | 30 | B/L | Vocal cord edema and paralysis, postcricoid edema | 1 | None | NG removal, gastrostomy placement | Yes | Alive | Gastrostomy support required even after 12 wk follow up |

| 4 | Stridor, troat pain | NG | 9 | B/L | Vocal cord paralyis and arytenoid edema | None | None | Removal of tube | Yes | Alive | Recovered completely 15 d after tube removal |

| 5 | Stridor, throat pain | NG | 18 | B/L | Vocal cord edema and post cricoid ulcer | NA | Coagulase positive staph aureus | NGT removal | Yes | Alive | One month after trach – VC mobile, but residual arytenoid edema |

| 6 | Throat pain, fever | NG | 5 | Vocal cord edema and post cricoid ulcer | NA | Streptococcus | NGT removal | No | Alive | ||

| 7 | Stridor | NA | 16 | Vocal cord edema and post cricoid ulcer | NA | None | Yes | Died | |||

| 8 | Stridor, fever | NG | NA | B/L | B/L vocal cord edema | NA | Candida albicans | NGT removal | Yes | Alive | 54 d after – both VC recovered sufficient abductor mobility and decannulation done |

| 9 | Stridor | NG | 2 | B/L | Impaired vocal cord abduction bilaterally. With edema. Postcricoid necrotic ulcer was noted, 1.5 cm in width | No | Mixed bacterial growth | NGT removal | Yes | Alive | No recovery till 1 month |

| 10 | SOB | NG | 2 | B/L | Isolated and complete abductor dysfunction of his vocal cords. With edema. Postcricoid ulceration | No | Mixed bacterial growth | NGT removal, steroids | Yes | Alive | Decannulated after 5 wk |

| 11 | Cough, sore throat | NG | 9 | Left VC paralysis | Left arytenoid fold swollen | No | None | NGT removal | No | Alive | None |

| 12 | Incidental | NG | 140 | Lt | Left- inhibited abductor movement | Yes | None | NG removal | Yes | Alive | Persistent VC palsy |

| 13 | Stridor, SOB | Long intestinal tube | 4 | B/L | Mild arytenoid edema | No | None | Removal of tube | Yes | Alive | Decannulated after 3 wk |

| 14 | Stridor | NG | 730 | B/L | B/L VC edema | No | None | NA | No | Died | |

| 15 | Stridor | NG | 75 | B/L | B/L VC edema | No | None | Frequent NG changes | No | Died | |

| 16 | Stridor, tachypnea, SOB | NG | 30 | B/L | Right VC paralysis, impaired left VC mobility, B/L edema | No | None | NGT removal, steroids | No | Alive | None |

| 17 | Stridor, SOB | NG | 35 | B/L | Bilateral arytenoid edema | No | None | NGT removal | Yes | Yes | Decannualted after 20 d |

| 18 | Stridor, desaturation, AMS | NG | 15 | B/L | Impaired abduction of the Vocal cords | No | None | NGT removal, steroids | No | Alive | None |

| 19 | Stridor, throat pain, desaturation | Long intestinal tube | 6 | B/L | B/L arytenoid edema | No | None | NGT removal | Yes | Alive | Decannulated after 4 wk |

| 20 | Stridor, throat pain, Respiratory distress | NG | 14 | B/L | Bilateral vocal cord palsy with severely compromised airway. | No | None | NGT removal, steroids | Yes | Alive | Improved after 4 wk |

| 21 | Stridor | NG | 14 | B/L | B/L VC palsy | No | None | NGT removal | No | Alive | None |

| 22 | Stridor, slurring of speech, sore throat, difficulty in swallowing, desaturation | NG | 7 | B/L | B/L vocal cord edema | No | None | NGT removal, steroids | Yes | Alive | A month to complete recovery |

| 23 | Wheezing, hoarseness | Nasointestinal ileus tube | 3 | B/L | Left arytenoid edema and erythema | No | None | Tube removal, steroids | No | Alive | None |

| 24 | Incidental | NG | 15 | B/L | Severe edema | No | None | Inhaled steroids | Yes | Alive | Decannulated after 5 wk |

| 25 | Stridor | NG | 105 | B/L | BL laryngeal edema | No | None | NGT removal | Yes | Alive | None |

| 26 | Desaturation | NG | 180 | Rt | Rt VC palsy | No | None | Neb steroids | NA | Alive | None |

| 27 | Stridor | NG | 760 | Rt | Rt VC palsy | No | None | Neb steroids | NA | Alive | None |

Proliferative interarytenoid granulation tissue and no abscess.

NG: Nasogastric; B/L: Bilateral; NA: Not available; SOB: Shortness of breath; VC: Vocal cords; NGT: Nasogastric tube.

The NGT syndrome is a serious and potentially life-threatening complication of NGT insertion. Even though the first description of this syndrome was in a case series of 12 patients published by Iglauer and Molt[23] in 1939, the term NGT syndrome was coined by Sofferman et al[6] in 1990. They described NGT syndrome as the development of throat pain and abductor dysfunction of vocal cords (VC) secondary to the presence of the NGT. It is suspected to result from ulceration and necrosis of the posterior cricoid region, leading to VC abduction paralysis[6].

The exact cause of NGT syndrome remains unknown. However, multiple mechanisms have been postulated, a combination of which may lead to the development of NGT syndrome. The first reason could be the dynamic and delicate larynx being constantly irritated by the semi-rigid NGT when the patient swallows or coughs. Secondly, the tonic contractile cricopharyngeus muscle continually presses the NGT against the posterior cricoid cartilage lamina, forming pressure ulcers. Thirdly, gravity pulls the larynx posteriorly in a supine patient, causing the NGT to be stuck between the rigid cricoid cartilage and the anterior cervical spine[5]. Finally, another proposed mechanism is the ischemia secondary to the compression of blood vessels supplying the posterior cricoarytenoid muscle by the NGT[11]. All these may lead to NGT causing persistent pressure, trauma and irritation on the posterior cricoid lamina, leading to ischemic necrosis, ulceration, and infection. This infection and necrosis of the posterior cricoid cartilage affect the function of the posterior cricoarytenoid muscles, which in turn affects the capacity of the larynx to abduct the VC, leading to respiratory compromise[5,11].

Diagnosis of NGT syndrome may be missed because of lack of awareness, non-specific symptomatology and delayed presentation after NGT insertion. Hence, only a few cases have been reported in the literature. Through this meta-summary, we intend to review and collate the available case reports and series data to understand the possible risk factors, signs and symptoms, and the clinical course of patients with NGT syndrome.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

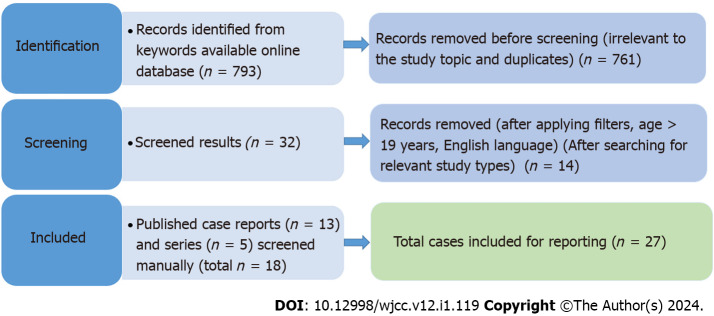

We conducted a systematic search for this meta-summary from the databases of PubMed, EMBASE, Reference Citation Analysis (https://www.referencecitationanalysis.com/) and Google scholar, from all the past studies till August 2023. The search terms included major MESH terms "Nasogastric tube", "Intubation, Gastrointestinal", "Vocal Cord Paralysis", and Syndrome. Further, it was filtered for the case reports published in the English language and on adult (> 18 years) humans. We manually screened all the search results and included the relevant literature for NGT syndrome. Duplicate articles from different search databases were excluded manually (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses flow diagram of the selected literature.

All the case reports and case series were evaluated, and the data were extracted for patient demographics, clinical symptomatology, diagnostic and therapeutic interventions, clinical course and outcomes. A datasheet for evaluation was further prepared.

Data Analysis

We prepared and evaluated the datasheet with the help of Excel and Microsoft Office 2019. Categorical variables were presented as frequency and percentage. Mean (SD) or median [interquartile range (IQR)] was used for continuous variables as appropriate. We applied a non-parametric correlational statistical test to test the non-parametric statistical hypothesis, as found appropriate. A P value of < 0.05 was deemed significant. Unless otherwise indicated, all the statistical analyses were done using SPSS (version 25.0, IBM SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). Tabulation and final documentation were done using MS Office software (MS Office 2019, Microsoft Corp, WA, United States).

RESULTS

Twenty-seven cases, from five case series and 13 case reports, of NGT syndrome were retrieved from our search, and published in literature till August 2023[6-22]. There was male predominance (17, 62.96%), and maximum number of cases were reported from the United States (10, 37.04%) and Japan (7, 25.93%). The age at presentation ranged from 28 to 86 years, with 22 (81.48%) aged 60 years or above. The median reported age was 73 years (IQR 61.5-77.0). Ten patients had diabetes mellitus (37.04%), and nine were hypertensive (33.33%). Other commonly reported comorbidities included chronic kidney disease (2, 7.4%), parkinsonism (2, 7.4%) and coronary artery disease (1, 3.7%). Only three (11.11%) patients were reported to be immunocompromised. The median time for developing symptoms after NGT insertion was 14.5 d (IQR 6.25-33.75 d).

The most commonly reported reason for NGT insertion was acute stroke (10, 37.01%), followed by peri-operative insertion (7, 25.93%) and altered mental status (3, 11.11%). The most commonly reported symptoms were stridor or wheezing 17 (62.96%), throat pain (7, 25.9%) and breathlessness (4, 14.8%). In 21, 77.78% of cases, bilateral VC were affected but in 3 patients (11.1%), only unilateral involvement was reported.

The only treatment instituted in most patients (21, 77.78%) was removing the NGT. However, few patients were also treated with systemic (7, 25.9%) or inhaled (4, 14.8%) steroids. Most patients (17, 62.96%) required tracheostomy for airway protection. But 8 of the 23 survivors recovered within five weeks and could be decannulated. Three patients (11.11%) were reported to have died (Table 3).

Table 3.

Clinical course of patients with nasogastric syndrome

|

Indication for NGT

|

Number of patients, n (%)

|

| Acute stroke | 10 (37.04) |

| Peri-operative period | 7 (25.93) |

| Altered mental status | 4 (14.81) |

| Gastrointestinal obstruction | 2 (7.41) |

| Traumatic brain or spinal cord injury | 2 (7.41) |

| GI bleed | 1 (3.7) |

| Acute pancreatitis | 1 (3.7) |

| Severe pneumonia with septic shock | 1 (3.7) |

| Toxic megacolon | 1 (3.7) |

| Presenting symptoms | |

| Stridor | 17 (62.96) |

| Sore throat/throat pain | 7 (25.93) |

| Shortness of breath | 4 (14.8) |

| Desaturation | 3 (11.11) |

| Speech disturbance | 4 (14.8) |

| Swallowing difficulty | 3 (11.11) |

| Cough | 1 (3.7) |

| Altered sensorium | 1 (3.7) |

| Incidental | 2 (7.41) |

| Type of feed NGT | |

| Nasogastric | 23 (85.19) |

| Long intestinal tube | 1 (3.7) |

| Naso-intestinal ileus tube | 2 (7.41) |

| NA | 1 (3.7) |

| Vocal cord involved | |

| Bilateral | 21 (77.78) |

| Left | 2 (7.41) |

| Right | 2 (7.41) |

| Therapeutic interventions | |

| Tube removal | 21 (77.78) |

| Systemic steroids | 7 (25.93) |

| Inhalational steroids | 4 (14.81) |

| Frequent change of nasogastric tube | 1 (3.7) |

| Tracheostomy procedure | |

| Yes | 17 (62.96) |

| No | 8 (29.63) |

| NA | 2 (7.41) |

| Final outcome | |

| Alive | 23 (85.19) |

| Dead | 3 (11.11) |

| NA | 1 (3.7) |

| Reported sequelae of NGT syndrome | |

| Improved after 3 wk | 4 (14.81) |

| Improved after 4 wk | 2 (7.41) |

| Partial improvement after 4 wk | 1 (3.7) |

| Improved after 5 wk | 2 (7.41) |

| Improved after 8 wk | 2 (7.41) |

| No recovery till 4 wk | 1 (3.7) |

| Persistent vocal cord palsy | 2 (7.41) |

| None reported | 8 (29.63) |

NG: Nasogastric; NGT: Nasogastric tube; NA: Not available; GI: Gastrointestinal.

DISCUSSION

The present review included data from 27 reported cases with a diagnosis of NGT syndrome, published in last five decades. More than 80% of patients were aged 60 years and above and 37.04% were reported to be diabetics. There was a considerable heterogeneity in the timing of onset of symptoms from NGT insertion (ranging 2 d to 2 years). In most of the patients, the only intervention required was NGT removal. Even though 62.96% required tracheostomy for airway protection, most of them showed complete recovery, with 8 of 23 survivors getting tracheostomy decannulation within five weeks.

NGT syndrome is a rare but potentially life-threatening complication of NGT insertion. It may be stipulated that the incidence of NGT syndrome may be much higher than reported and the diagnosis is largely missed, as many patients may have minor symptoms or are misdiagnosed. Further, many patients requiring NGT are too sick to report any symptoms and hence, the diagnosis largely depends on the suspicion of treating physicians. Wolff and Kessler[24], evaluated larynges of 149 patients by performing a post-mortem, who have had NGT in situ for more than 48 h and reported that 35% had post-cricoid ulcers present[24]. This may suggest, in critically ill patients requiring NGT for more than 48 h, the incidence may be much higher, warranting a high index of suspicion in such patients.

The non-specific symptoms related to NGT syndrome are frequently missed or attributed to other common diseases like asthma or infection. Throat pain has been described as an important and early presenting complaint and is a component of the classical triad defined by Sofferman et al[6] However, critically ill patients or those with altered mental status may not be able to complain of pain and hence the diagnosis may be missed or delayed. In our review, throat pain was reported in only 7, 25.93% of patients, and stridor was the most commonly reported symptom, present in almost 17, 62.96% of patients. As most of these patients had neurological dysfunction or were critically ill, throat pain might not have been reported. Hence, the presence of stridor or wheeze in a patient with NGT should alert the treating physician towards the possibility of NGT syndrome. Symptoms like breathlessness, desaturation or respiratory distress develop late and are suggestive of advanced disease requiring prompt medical intervention. If early signs are missed, patients with NGT syndrome may present with life-threatening respiratory distress, which may require emergency tracheostomy to maintain the airway.

The presence of comorbidities may also affect the incidence of NGT syndrome. Diabetes Mellitus has been reported to increase the risk of developing NGT syndrome, which was also reported to be present in 10, 37.04% of cases in our review[6]. The other reported risk factors include the presence of GER leading to an acidic environment in the post-cricoid region and the presence of NGT at the level of the lower oesophageal sphincter which may reduce its function[25].

Classically NGT syndrome has been described to affect both the VC[6]. However, as the awareness regarding this syndrome increased over the years, multiple unilateral varieties of NGT syndrome have been described[8,9,22]. Three patients (11.11%) in our review had only unilateral VC involvement.

Symptoms of NGT syndrome have been shown to develop even two days after NGT insertion[2] but may be delayed up to two years[11]. This heterogeneity in presentation and lack of predictability makes the diagnosis more challenging.

Diagnosis of NGT syndrome requires direct visualisation of the VC and the post-cricoid area. Culture or biopsy may not be required for the diagnosis but may be helpful in ruling out any secondary infection and instituting appropriate antibiotics. As the diagnosis requires an invasive procedure, patients with minor symptoms like sore throat and hoarseness of voice may not warrant such a procedure and hence may be missed.

The only treatment instituted in most of the patients (73.9%) was the removal of the NGT. Oral ingestion of food should be avoided as it may lead to aspiration due to VC palsy. Re-insertion of a softer NGT of a smaller size has also been shown to prevent the development of NGT syndrome[17]. Although NGT syndrome has been reported even with smaller size tubes, the effect of size remains unknown because most of the case reports on NGT syndrome did not mention the size of NGT used[22]. Although it seems prudent that the use of a smaller and softer NGT, if the patient’s condition allows, may prevent the development of NGT syndrome.

Even though inhaled or intravenous steroids were used in some patients, its role remains debatable. However, it may be instrumental in reducing inflammation and may provide early symptomatic relief in patients with severe symptoms. But, the risk of secondary infections must be kept in mind while prescribing corticosteroids in critically ill patients. Hence, corticosteroids if used, should be for short duration and considering risk-benefit in patients with severe airway obstruction.

Complications of NGT syndrome include acute respiratory failure and the formation of retro-cricoid abscesses. Airway compromise secondary to VC palsy may necessitate tracheostomy for maintaining the airway. The presence of an endotracheal tube may prevent VC healing. Hence, tracheostomy may be preferred in such patients. The tracheostomy tube should be removed only after the resolution of VC palsy, which, in most of these cases, occur between few weeks to months. In our review, even though most of the patients required tracheostomy, they could be successfully decannulated over the next few weeks.

There are several strengths to our analysis. We have included all the published cases on NGT syndrome till date. As we selected only adult cases, the data collected is more homogenous and applicable to adult healthcare. This being a meta-summary of case series and case reports, it has some inherent limitations. The data was collected from case series and case reports, and thus, there was no control arm, studies were heterogeneous, and prone to high risk of bias and missing data. This may affect the generalisability of the results. The present study is a meta-summary of published case reports and series, and there are significant deficits of data in these papers, and data regarding any dysphagia assessment, probe usage, or assistance provided by rehabilitation teams was not present and scarcely reported. Hence, this could not be commented on in our study. However, as these are very important aspects of understanding the natural history and course of NGT syndrome, we also recommend including these data in future research or report papers.

CONCLUSION

NGT syndrome is an uncommon clinical complication of a very common clinical procedure. However, an underreporting is possible because of misdiagnosis, or lack of awareness among clinicians. Patients in early stages and with mild symptoms may be missed. Further, high variability in the timing of presentation after NGT insertion makes diagnosis challenging. Hence, a high index of suspicion is warranted to make a diagnosis. Early diagnosis and prompt removal of NGT may suffice in most patients, but a significant proportion of patients presenting with respiratory compromise may require tracheostomy for airway protection. The long-term outcomes remain favourable with complete resolution of symptoms in most of the cases.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

The risks associated with nasogastric tube (NGT) placement are often underestimated. Upper airway obstruction with a NGT is an uncommon but potentially life-threatening complication.

Research motivation

NGT syndrome is potentially life–threatening, and early diagnosis is the key to prevention of fatal upper airway obstruction. Lack of specific signs and symptoms and inability to prove temporal relation with NGT insertion, has made diagnosing the syndrome quite challenging.

Research objectives

To review and collate the data from the published case reports and case series, to understand the possible risk factors, early warning signs and symptoms for timely detection to prevent the manifestation of the complete syndrome with life-threatening airway obstruction.

Research methods

We conducted a systematic search, from the database of PubMed from all the past studies till August 2023. The search terms included major MESH terms "Nasogastric tube", "Intubation, Gastrointestinal", "Vocal Cord Paralysis", and “Syndrome”. Further, it was filtered for the case reports published in the English language and on adult (> 18 years) humans.

Research results

Twenty-seven cases, from five case series and 13 case reports, of NGT syndrome were retrieved. There was male predominance (62.96%), and the age at presentation ranged from 28 to 86 years. The median time taken for developing symptoms after NGT insertion was 14.5 d (interquartile range 6.25-33.75 d). The most commonly reported reason for NGT insertion was acute stroke (37.01%), and the most commonly reported symptoms were stridor or wheezing (62.96%). The only treatment instituted in most of patients (77.78%) was removing the NGT. The majority (62.96%) of patients required tracheostomy for airway protection, but only three deaths were reported.

Research conclusions

NGT syndrome is an uncommon clinical complication of a very common clinical procedure. Early diagnosis and prompt removal of NGT may suffice in most patients, but a significant proportion of patients presenting with respiratory compromise may require tracheostomy for airway protection.

Research perspectives

A high index of suspicion is required for diagnosis of NGT syndrome. Further studies may aid in identifying the risk factors and help in early diagnosis.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: All the authors report no relevant conflicts of interest for this article.

PRISMA 2009 Checklist statement: The authors have read the PRISMA 2009 Checklist, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the PRISMA 2009 Checklist.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Peer-review started: October 28, 2023

First decision: December 5, 2023

Article in press: December 18, 2023

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: India

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Arakawa-Sugueno L, Brazil S-Editor: Li L L-Editor: A P-Editor: Li L

Contributor Information

Deven Juneja, Department of Critical Care Medicine, Max Super Speciality Hospital, New Delhi 110017, India. devenjuneja@gmail.com.

Prashant Nasa, Department of Critical Care Medicine, NMC Specialty Hospital, Dubai 7832, United Arab Emirates.

Gunjan Chanchalani, Department of Critical Care Medicine, Karamshibhai Jethabhai Somaiya Hospital and Research Centre, Mumbai 400022, India.

Ravi Jain, Department of Critical Care Medicine, Mahatma Gandhi Medical College and Hospital, Jaipur 302022, Rajasthan, India.

References

- 1.Agarwala S, Dave S, Gupta AK, Mitra DK. Duodeno-renal fistula due to a nasogastric tube in a neonate. Pediatr Surg Int. 1998;14:102–103. doi: 10.1007/s003830050451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Newton M, Burnham WR, Kamm MA. Morbidity, mortality, and risk factors for esophagitis in hospital inpatients. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2000;30:264–269. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200004000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lai PB, Pang PC, Chan SK, Lau WY. Necrosis of the nasal ala after improper taping of a nasogastric tube. Int J Clin Pract. 2001;55:145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stein M, Caplan ES. Nosocomial sinusitis: a unique subset of sinusitis. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2005;18:147–150. doi: 10.1097/01.qco.0000160904.56566.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sofferman RA, Hubbell RN. Laryngeal complications of nasogastric tubes. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1981;90:465–468. doi: 10.1177/000348948109000510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sofferman RA, Haisch CE, Kirchner JA, Hardin NJ. The nasogastric tube syndrome. Laryngoscope. 1990;100:962–968. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199009000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Apostolakis LW, Funk GF, Urdaneta LF, McCulloch TM, Jeyapalan MM. The nasogastric tube syndrome: two case reports and review of the literature. Head Neck. 2001;23:59–63. doi: 10.1002/1097-0347(200101)23:1<59::aid-hed9>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.To EW, Tsang WM, Pang PC, Cheng JH, Lai EC. Nasogastric-tube-induced unilateral vocal cord palsy. Anaesthesia. 2001;56:695–696. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.2001.02137-8.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nehru VI, Al Shammari HJ, Jaffer AM. Nasogastric tube syndrome: the unilateral variant. Med Princ Pract. 2003;12:44–46. doi: 10.1159/000068162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sanaka M, Kishida S, Yoritaka A, Sasamura Y, Yamamoto T, Kuyama Y. Acute upper airway obstruction induced by an indwelling long intestinal tube: attention to the nasogastric tube syndrome. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38:913. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200411000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Isozaki E, Tobisawa S, Naito R, Mizutani T, Hayashi H. A variant form of nasogastric tube syndrome. Intern Med. 2005;44:1286–1290. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.44.1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marcus EL, Caine Y, Hamdan K, Gross M. Nasogastric tube syndrome: a life-threatening laryngeal obstruction in a 72-year-old patient. Age Ageing. 2006;35:538–539. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afl042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vielva del Campo B, Moráis Pérez D, Saldaña Garrido D. Nasogastric tube syndrome: a case report. Acta Otorrinolaringol Esp. 2010;61:85–86. doi: 10.1016/j.otorri.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim T, Kim SM, Sohn SB, Lee YH, Lim SY, Sim JK. Nasogastric Tube Syndrome: Why Is It Important in the Intensive Care Unit? Acute Crit Care. 2015;30:231–233. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sano N, Yamamoto M, Nagai K, Yamada K, Ohkohchi N. Nasogastric tube syndrome induced by an indwelling long intestinal tube. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:4057–4061. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i15.4057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perera HMM. NG tube syndrome: a case report of a rare complication of NG tube. Ceylon Med J. 2018;63:192–193. doi: 10.4038/cmj.v63i4.8773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kanbayashi T, Tanaka S, Uchida Y, Hatanaka Y, Sonoo M. Nasogastric Tube Syndrome: The Size and Type of the Nasogastric Tube May Contribute to the Development of Nasogastric Tube Syndrome. Intern Med. 2021;60:1977–1979. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.6258-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yildiz E, Öner Ö, Koçak Ö, Yildirim N. A case report: probably concurrent nasogastric tube syndrome and cerebrovascular disease in a postoperative patient. BSJ Health Sci. 2021;4:153–155. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taira K, Koyama S, Morisaki T, Fukuhara T, Donishi R, Fujiwara K. Nasogastric Tube Syndrome: A Severe Complication of Nasointestinal Ileus Tube. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2022;17:191–196. doi: 10.1159/000526715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cui W, Xiang J, Deng X, Qin Z. Difficult tracheostomy decannulation related to nasogastric tube syndrome: A case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2023;110:108734. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2023.108734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nihira T, Fukaguchi K, Taguchi A, Fukui H, Sekine I, Yamamoto D, Moriya H, Yamagami H. Bilateral vocal cord palsy induced by long-term use of small-bore nasogastric tube. Acute Med Surg. 2023;10:e872. doi: 10.1002/ams2.872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paul T, Shdid RKA, Khan SHU. Unilateral Variant of NGT Syndrome: An Uncommon Complication of a Very Common Intervention. Gerontol Geriatr Med. 2023;9:23337214231172626. doi: 10.1177/23337214231172626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iglauer S, Molt WF. LXXI Severe Injury to the Larynx Resulting from the Indwelling Duodenal Tube (Case Reports) Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1939;48:886–904. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wolff AP, Kessler S. Iatrogenic injury to the hypopharynx and cervical esophagus: an autopsy study. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1973;82:778–783. doi: 10.1177/000348947308200605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dotson RG, Robinson RG, Pingleton SK. Gastroesophageal reflux with nasogastric tubes. Effect of nasogastric tube size. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;149:1659–1662. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.149.6.8004326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]