Abstract

Complications involving the heart are rare in leptospirosis, and cardiac tamponade is still rarer. We report the case of a 42-year-old hypertensive woman who presented with complaints of cough for 2 months and breathlessness for 1 month. One month later, she developed shortness of breath and loss of consciousness. The patient had a history of hemiparesis. Serum anti-Leptospira immunoglobulin M ELISA was positive. Ultrasound showed pericardial tamponade and hemorrhagic collection. Two-dimensional echocardiography showed minimal effusion posterior to the left ventricle and no effusion present to the right ventricle. High-resolution computerized tomography revealed patchy areas of ground glass opacities in bilateral upper and bilateral lower lobes, prominent bronchovascular markings bilaterally, and minimal pericardial thickening. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain showed small chronic infarcts in bilateral corona radiata and basal ganglia. A magnetic resonance angiogram of the brain showed a basilar top aneurysm, which was an incidental finding. No signs of rupture of the aneurysm were seen. Digital subtraction angiography showed 50%–70% stenosis at the junction of the V3–V4 segments of the vertebral artery. The right lower limb immobilization, along with ecosprin, ivabradine, amlodipine, and fluconazole, was started, to which the patient responded well.

Keywords: Aneurysms, basilar arteries, cardiac tamponades, leptospiroses, pericardial effusions

INTRODUCTION

Leptospirosis is a bacterial disease caused by pathogenic spirochetes of the genus Leptospira. It mostly manifests as pyrexia with chills, nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal aches, exanthema, conjunctivitis, and jaundice. Cardiovascular complications are very rare, and very few cases can be found in literature, and cardiac tamponade is a far more rare complication.[1] We report the case of a 42-year-old woman who had presented with a cough for 2 months and breathlessness for 1 month. One month later, she developed breathlessness and loss of consciousness. Serum anti-leptospira immunoglobulin M ELISA was positive. Ultrasound showed pericardial tamponade and hemorrhagic collection. Digital subtraction angiography (DSA) showed stenosis of the vertebral artery.

CASE REPORT

A 42-year-old woman with a past medical history of hypertension and stroke with residual the right-sided hemiparesis presented to the emergency department with complaints of cough for 2 months and breathlessness for 1 month. A month after the initial presentation, the patient developed shortness of breath and loss of consciousness and was admitted to the critical care medicine department. He did not have pallor or icterus; cyanosis was present, and clubbing was absent. His temperature was 99.2°F (axillary), respiratory rate was 28/min, blood pressure was 108/68 mmHg (expiratory) and 96/70 mmHg (inspiratory) (suggestive of pulsus paradoxus), and the pulse rate was 108/min, with no radio-radial or radio-femoral delay. The jugular venous pressure was raised (10 cm of water) with appreciable jugular venous distension and distended neck veins. On auscultation, heart sounds were muffled, and there was an area of dullness in the area just below the left scapula. Before intubation, her Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score was E4V2M4. She was intubated due to altered sensorium and respiratory failure, with shallow and labored breathing pattern, and her GCS score was E4V1(T) M4; pupils were reactive to light, power assessed on sedation seemed to be 3/5 in all four limbs, and all pulses were felt equally (high volume). Three years back, she had again developed the right-sided hemiparesis, along with hypertensive emergency.

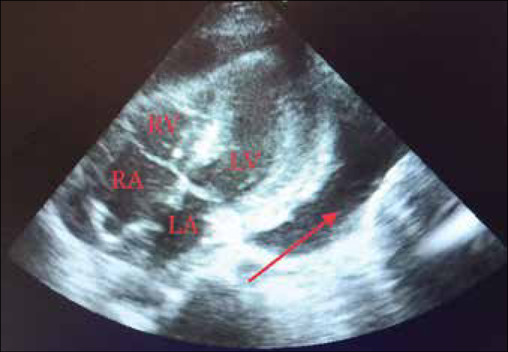

Chest X-ray showed signs of pericardial effusion. Ultrasound findings showed pericardial tamponade and hemorrhagic collection. A pericardial drain was inserted in the pericardial cavity at bedside, guided by echocardiography. Two-dimensional (2D) echocardiography revealed minimal effusion posterior to the left ventricle and no effusion present around the right ventricle [Figure 1]. High-resolution computerized tomography findings revealed patchy areas of ground-glass opacities in the bilateral upper and bilateral lower lobes, prominent bronchovascular markings in both lungs, and minimal pericardial thickening. The laboratory investigation findings are summarized in Table 1. Pericardial fluid cytology showed no malignant cells. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain showed small chronic infarcts in bilateral corona radiata and basal ganglia. A magnetic resonance angiogram of the brain showed basilar top aneurysm, which was an incidental finding. No signs of rupture of the aneurysm were seen. DSA and endovascular coiling were planned. DSA showed 50%–70% stenosis at the junction of the V3-V4 segments of the vertebral artery. The length of the lesion was approximately 4 mm; saccular aneurysm was seen at the basilar top with a dome measuring 4.7 mm × 3.5 mm and neck measuring approximately 3 mm.

Figure 1.

Two-dimensional echocardiography (subcostal view) showing minimal effusion posterior to the left ventricle (marked by red arrow) and no effusion present around the right ventricle. (RA: Right atrium; RV: Right ventricle; LA: Left atrium; LV: Left ventricle)

Table 1.

Summary of the laboratory investigations of the patient

| Laboratory investigation | Patient value | Normal value |

|---|---|---|

| Complete blood count | ||

| Red blood count | 4.2 | 3.6-5 |

| Total Leukocyte count | 6800 | 4000-11000 |

| Differential Leukocyte count | 75/15/5/10 | 55-70/20-40/2-8/1-4/0.5-1 |

| Platelet count | 50000 | 1.5-4.5 lac |

| Microbiological profile | ||

| Serum anti-leptospira IgM enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) | Positive | Negative |

| Serum anti-scrub typhus IgM ELISA | Negative | Negative |

| Serum salmonella typhi IgM | Negative | Negative |

| Blood aerobic bacterial culture | Sterile | Sterile |

| Cartridge based nucleic acid amplification test (CBNAAT) of the pericardial fluid for Mycobacterium tuberculosis | Negative | Negative |

| Further investigation | ||

| Serum procalcitonin (ng/mL.) | 3.14 | <0.10- absence of bacterial infection 0.10-0.25- bacterial infection unlikely 0.26-0.50- bacterial infection is possible >0.50- suggestive of presence of bacterial infection |

| Pericardial fluid lactate dehydrogenase (IU/L) | 4194 | 276-517 |

| Antinuclear Antibody | 3+ | |

| Cardiolipin (IgM) (LU/mL) | <3 | Negative- <12 Equivocal- 12-18 Positive- >18 |

| Beta-2-glycoprotein (IgG) (AU/mL) | 4 | Negative- <12 Equivocal- 12-18 Positive- >18 |

| PR-3 antibodies (AU/mL) | <3 | Negative- <12 Equivocal- 12-18 Positive- >18 |

| Myeloperoxidase antibodies (AU/mL) | <3 | Negative- <12 Equivocal- 12-18 Positive- >18 |

| Factor V Leiden mutation | Negative | Negative |

The patient was started on IV Doxycycline 100 mg BID for 10 days. Following this, coiling was done. The right lower limb immobilization for 8 h was advised, along with the tablet Ecosprin 150 mg by mouth daily for 14 days, in view of the left vertebral artery stenosis. Tablet ivabradine 5 mg BID by mouth daily for 14 days, tablet amlodipine 5 mg OD for 14 days, and tablet fluconazole 200 mg once, followed by 100 mg QID for 13 days, were also given. Eventually, the patient recovered and was discharged after 3 weeks of hospitalization. The patient was followed up after 2 weeks of discharge in the outpatient department and was stable.

DISCUSSION

Leptospira is a genus of bacteria that includes two species Leptospira interrogans (pathogenic, with more than 218 serovars) and Leptospira biflexa (nonpathogenic, with more than 60 serovars).[2] Leptospirosis spreads due to contact with urine or corporal fluids of infected animals or to individuals who consume or are in contact with water or ground infected by that urine or corporal fluids. Leptospirosis, a zoonotic disease, affecting most mammals, is most common in tropical and subtropical regions and mostly occurs from summer to autumn, including the rainy season. The most commonly affected population includes veterinarians, ranchers, and rice-field workers. The incubation period ranges from 2 to 28 days.[1,3] Leptospirosis has a biphasic pattern, including early flu-like, septicemic illness and a second–inflammatory phase, marked by systemic inflammatory response syndrome or cytokine storm.[2] The common clinical manifestations range from asymptomatic form to anicteric fever, chills, nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, exanthema, conjunctivitis, headache, and jaundice. The most aggressive form reported is the icteric hemorrhagic form, better known as Weil's disease.[1,3] Some other diseases like COVID-19 and dengue can be possible differential diagnoses. COVID-19 may have a similar course and may make the diagnosis more tough, especially in the tropics and more so commonly in travelers or migrants to nonendemic areas. Second, it is pertinent to consider leptospirosis when dengue is detected in a patient with severe acute febrile illness because early antibiotics may prove to be effective.[2]

Cardiovascular consequences are relatively rare and less reported.[1,3] Diagnosis is made by a combination of clinical and laboratory criteria. Modified Faine's criteria is one of the most sensitive tools for diagnosing leptospirosis.[4]

Only a few literature report the occurrence of myopericarditis[5] and arrhythmia following leptospirosis, whereas cardiac tamponade is a still rarer entity to be found.[6] In a case series from a single ward of a Sri Lankan hospital, during a 1-month period, six patients of suspected leptospirosis were admitted. Five of them had contracted severe leptospirosis with cardiac involvement. All of them developed shock. Two had also developed rapid atrial fibrillation. One had dynamic T-wave changes and the other two had sinus tachycardia. In two patients, myocarditis was noted in 2D echocardiogram, whereas in the other two, there were nonspecific findings, and the remaining one had a normal 2D echocardiogram. All the patients had increased titers of cardiac troponin I, which eventually got normalized in due course of treatment and recovery. All five had developed acute kidney injury. Four of them required inotropic/vasopressor medications to maintain their blood pressure and one patient recovered from shock only with fluid resuscitation. After recovery, no patient showed residual complications.[7] However, an autopsy study in 2008 reported that the incidence of cardiac abnormalities secondary to leptospirosis is more often than not, due to myocarditis and with different levels of involvement of the epicardium and/or endocardium, the coronary arteries, or the valves, although the patient may or may not manifest with any symptoms.[8] In yet another 2021 case report, a 32-year-old male patient had presented with ST-segment elevation after 14 days of cross-country race. Pericarditis was diagnosed and was linked to an episode of acute leptospirosis that was confirmed by serological examination.[9] Another 29-year-old male patient, with leptospirosis, had no classical clinical manifestation except shock. Within 24 h of admission, there was chest pain which led to the suspicion of a cardiac involvement, which was confirmed by diffuse supra-ST segment elevation, increased levels of troponin and NT-proBNP and an electrocardiogram showing mild left ventricular ejection fraction (48%–50%).[10]

CONCLUSION

Although a rare finding, cardiac abnormalities should not be completely ruled out while managing a patient of leptospirosis. cardiac abnormalities are mostly asymptomatic, and often manifest when it is severe or when there are manifestations of other secondary complications. Moreover, life-threatening complications like hemorrhagic cardiac tamponade might also present rarely. Hence, routine cardiac check-up should be done whenever possible, or where resources are abundant.

Research quality and ethics statement

This case report did not require approval by the institutional ethics committee. The authors followed applicable EQUATOR Network (http://www.equator-network.org/) guidelines, specifically the CARE guideline, during the conduct of this research project.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors verify that written informed consent was obtained from the subject to publish de-identified information and findings in the journal, but understands that complete anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pérez-Cervera J, Vaello-Paños A, Dávila-Dávila E, Delgado-Expósito G, Morales-Martínez de Tejada Á, Aranda-López CA, et al. Cardiac tamponade secondary to leptospirosis. A rare association: A case report. J Cardiol Cases. 2021;23:140–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jccase.2020.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gompf SG. Leptospirosis. [Last accessed on 2023 Jun 24];Medscape. Available from: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/220563-overview?icd=login_success_gg_match_norm#a1 . [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yücel Koçak S, Kudu A, Kayalar A, Yilmaz M, Apaydin S. Leptospirosis with acute renal failure and vasculitis: A case report. Arch Rheumatol. 2019;34:229–32. doi: 10.5606/ArchRheumatol.2019.7063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bandara K, Weerasekera MM, Gunasekara C, Ranasinghe N, Marasinghe C, Fernando N. Utility of modified Faine's criteria in diagnosis of leptospirosis. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:446. doi: 10.1186/s12879-016-1791-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cavalcanti SL, Lerena V, Gomez C. Acute myopericarditis. An uncommon presentation of severe Leptospirosis – A case report and literature review. Int J Trop Dis. 2018;1:009. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yeşilbaş O, Kıhtır HS, Yıldırım HM, Hatipoğlu N, Şevketoğlu E. Pediatric fulminant leptospirosis complicated by pericardial tamponade, macrophage activation syndrome and sclerosing cholangitis. Balkan Med J. 2016;33:578–80. doi: 10.5152/balkanmedj.2016.151240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jayathilaka PG, Mendis AS, Perera MH, Damsiri HM, Gunaratne AV, Agampodi SB. An outbreak of leptospirosis with predominant cardiac involvement: A case series. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19:265. doi: 10.1186/s12879-019-3905-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chakurkar G, Vaideeswar P, Pandit SP, Divate SA. Cardiovascular lesions in leptospirosis: An autopsy study. J Infect. 2008;56:197–203. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zechel M, Franz M, Baier M, Hagel S, Schleenvoigt BT. Pericarditis as a cardiac manifestation of acute leptospirosis. Infection. 2021;49:349–53. doi: 10.1007/s15010-020-01496-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barcelos V, Ferreira AC, Fontes AX, Dias L, Costa H, Martins D. Cardiac Involvement in leptospirosis – An unusual manifestation. Eur J Case Rep Int Med. 2020;7:7. [Google Scholar]