Abstract

Mycelia of Gibberella zeae (anamorph, Fusarium graminearum), an important pathogen of cereal crops, are yellow to tan with white to carmine red margins. We isolated genes encoding the following two proteins that are required for aurofusarin biosynthesis from G. zeae: a type I polyketide synthase (PKS) and a putative laccase. Screening of insertional mutants of G. zeae, which were generated by using a restriction enzyme-mediated integration procedure, resulted in the isolation of mutant S4B3076, which is a pigment mutant. In a sexual cross of the mutant with a strain with normal pigmentation, the pigment mutation was linked to the inserted vector. The vector insertion site in S4B3076 was a HindIII site 38 bp upstream from an open reading frame (ORF) on contig 1.116 in the F. graminearum genome database. The ORF, designated Gip1 (for Gibberella zeae pigment mutation 1), encodes a putative laccase. A 30-kb region surrounding the insertion site and Gip1 contains 10 additional ORFs, including a putative ORF identified as PKS12 whose product exhibits about 40% amino acid identity to the products of type I fungal PKS genes, which are involved in pigment biosynthesis. Targeted gene deletion and complementation analyses confirmed that both Gip1 and PKS12 are required for aurofusarin production in G. zeae. This information is the first information concerning the biosynthesis of these pigments by G. zeae and could help in studies of their toxicity in domesticated animals.

Gibberella zeae (anamorph, Fusarium graminearum) is an important pathogen of corn, wheat, barley, and rice. This fungus produces a broad range of secondary metabolites, including mycotoxins, antibiotics, and pigments (30, 32, 33). The growth of the fungus on potato dextrose agar (PDA) is rapid, resulting in dense aerial mycelia that are frequently yellow to tan with white to carmine red margins and have undersurfaces that usually are carmine red. This pigmentation pattern also characterizes several other species in the Discolor section, including Fusarium culmorum and Fusarium crookwellense (33). Two pigments produced by G. zeae and F. culmorum, aurofusarin and rubrofusarin, are golden yellow and red, respectively (2, 9, 38). Aurofusarin is a dimeric naphthoquinone that is toxic to poultry (6, 7). Ingestion of this pigment causes significant decreases in the concentrations of vitamins A and E, total carotenoids, lutein, and zeaxanthin in quail egg yolk and increased susceptibility to lipid peroxidation (6). Naturally occurring aurofusarin also has been reported in Fusarium-infected wheat (20). The biological activities of rubrofusarin include antimycobacterial and antiallergic activities, and this compound is phytotoxic to weeds, such as Amaranthus hypochondriacus L. and Echinochloa crus-galli (L.) Beuv. (8, 18, 29).

Many filamentous fungi produce pigments, such as melanins (23, 37, 41), green and bluish green conidial pigments (22, 31, 40), and red pigments (10, 26). These fungal polyketide pigments have been studied intensively because of their biological importance. Fungal melanin contributes to the virulence of melanin-producing pathogens in both plant and animal hosts, as well as to the survival and longevity of fungal propagules (23, 41). The conidial pigments of Aspergillus fumigatus and Aspergillus nidulans may be important for virulence in an animal host (22, 39) or for protection of the conidia against oxidative attack (15). Bikaverin, a red pigment produced by Gibberella fujikuori, has antiprotozoan and antifungal activities (26). In addition, some fungal polyketide pigments are considered undesirable cometabolites whose production complicates industrial fermentation processes (5, 26). The biosynthesis of these polyketide pigments is initiated by the multifunctional enzyme polyketide synthase (PKS) (13, 14).

Fungal PKSs consist of a single peptide with conserved enzymatic domains (namely, β-ketoacyl synthase, acyl transferase, and phosphopantetheine attachment site [acyl carrier protein] domains) and sometimes one or more of the following domains: dehydratase, enoyl reductase reductase, β-ketoacyl reductase, and thioesterase (13, 14). All of the known PKSs required for production of fungal pigments have the same domain structure and belong to the same enzyme class, the nonreducing PKSs (21). They all lack the domains responsible for reduction of a polyketide backbone (enoyl reductase reductase, dehydratase, and β-ketoacyl reductase).

The objectives of this study were to isolate and characterize one or more of the genes responsible for pigment biosynthesis by G. zeae and to test the hypothesis that a PKS gene, similar to the genes that participate in the biosynthesis of other fungal pigments, is involved in the production of aurofusarin, the polyketide pigment of G. zeae. Our results provide the first information on the biochemical biosynthesis of aurofusarin by G. zeae and could be used to evaluate the biological significance of aurofusarin to this fungus.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and media.

Strains SCKO4 and Z03643 were used as wild-type strains of G. zeae. SCKO4, a lineage 6 strain, is a nivalenol producer, and Z03643, a lineage 7 strain, produces deoxynivalenol and zearalenone (34). Mutant strain S4B3076 was derived from SCKO4 by using restriction enzyme-mediated integration (REMI) mutagenesis (28, 43). For pigment production, SCKO4 was grown on PDA (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) for 2 weeks at 25°C in the dark, after which the cultures were harvested, dried in a ventilated hood, and ground in a blender for pigment extraction. For DNA isolation, the fungal strains were grown in 100 ml of complete medium (4) in 250-ml Erlenmeyer flasks for 3 days at 25°C on a rotary shaker at 150 rpm. For extraction of total RNA, aerial mycelia of SCKO4 grown on carrot agar (19) were used. Carrot agar also was used for sexual crosses (3).

REMI mutagenesis and fungal transformation.

Protoplasts of G. zeae strain SCKO4 or Z03643 (1.5 × 105 protoplasts in 150 μl of 1.2 M sorbitol-10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5]-10 mM CaCl2) were prepared by treatment of young mycelia grown on YPG liquid medium (3 g of yeast extract per liter, 10 g of peptone per liter, 20 g of glucose per liter) for 12 h at 25°C with Drisealse (10 mg/10 ml of NH4Cl; InterSpex Products, Inc., San Mateo, Calif.) as previously described (25, 44) and were transformed in the presence or absence of restriction enzymes. The REMI procedure was modified from previous protocols (28, 43). One hundred micrograms of plasmid pBCATPH (42) was linearized by digestion with 80 U of HindIII for 3 h in a 100-μl reaction mixture and added to a protoplast suspension of G. zeae strain SCKO4 along with an additional 80 U of HindIII. Stable REMI transformants were selected on regeneration medium containing hygromycin B (75 μg/ml) and were stored in 25% glycerol at −80°C.

Nucleic acid manipulations, PCR conditions, and sequencing.

Fungal genomic DNA was extracted as previously described (16). Escherichia coli colonies carrying recombinant plasmids were screened by using a single-tube miniprep method (27). For fungal transformation, plasmids were purified from 5 ml of E. coli cultures by using a plasmid purification kit (NucleoGen Biotech, Siheung, Korea). Total RNA was extracted from mycelia (0.1 to 0.2 g, wet weight) by using 1 ml of TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Standard procedures were used for restriction endonuclease digestion, ligation, agarose gel electrophoresis, and gel blotting (35). 32P-labeled probes were used in both DNA and RNA gel blot hybridization. PCR primers (Bioneer Corporation, Chungwon, Korea) were resuspended at a concentration of 100 μM in sterilized water and stored at −20°C. PCR was performed as described previously (25). DNA sequencing was performed at the National Instrumentation Center for Environmental Management (Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea). Sequencing of the rescued plasmids was initiated close to the HindIII site on the REMI vector pBCATPH (42) with the specific primers pBCATPH/p1 (5′-GCTGGCGAAAGGGGGATGTGCT-3′) and pBCATPH/p3 (5′-TCCTATGAGTCGTTTACCCAGAAT-3′). Nucleotide sequences were assembled by using the SeqMan program (DNASTAR, Inc., Madison, Wis.) and were analyzed with the MegAlign and MapDraw programs (DNASTAR, Inc.). Sequences were compared with the F. graminearum genome database at http://www.broad.mit.edu/annotation/fungi/fusarim/index.html by using BLAST (National Center for Biotechnology Information; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov).

Double-joint PCR.

A transforming DNA fragment carrying a hygromycin resistance gene (hygB) flanked by DNA sequences homologous to the sequences located at the 5′ and 3′ ends of the genomic target region was amplified by using double-joint PCR, with modifications (11). To delete Gip1, DNA fragments corresponding to regions 5′ (1.1 kb) and 3′ (1.2 kb) of the Gip1 open reading frame (ORF) were amplified from genomic DNA of SCKO4 with primer pairs G1-5′f (5′-CATGGCTGAACAGGAACTTG-3′)-G1-5′r (5′-CAGGTACACTTGTTTAGAGCGCTGTCAGCTTATTGCAGT-3′) and G1-3′f (5′-TCAATATCATCTTCTGTCGTGTTATCGTGCTTCCATTTG-3′)-G1-3′r (5′-GATGAACCGCTACACTCCTG-3′), respectively. A 1.9-kb fragment containing the hygB gene under the control of the A. nidulans trpC promoter and terminator was amplified from the vector pBCATPH (42) with primers HygB-f (5′-CTCTAAACAAGTGTACCTGTGC-3′) and HygB-r (5′-CGACAGAAGATGATATTGAAGG-3′). The sequences underlined in primers HygB-f and HygB-r were added to the 5′ ends (indicated by underlining) of primers G1-5′r and G1-3′f, respectively, to promote hybridization between the PCR products amplified by these primers. Three amplicons (the 5′ flanking region of Gip1, the hygB cassette, and the 3′ flanking region of Gip1) were mixed at a 1:2:1 molar ratio and used as the template for a second round of PCR with a new primer pair (NG1-5′f [5′-CATTGGTTGGAGCAAAGA-3′] and NG1-3′r [5′-TACCTTTGACCTCAAGCC-3′], which are nested in G1-5′f and G1-3′r, respectively), which resulted in a 4.1-kb fragment carrying the hygB cassette fused to the Gip1 flanking regions.

By using the same strategy, a 4.4-kb fusion PCR product was amplified for the deletion of PKS12; the primer pairs P12-5′f (5′-GCGACTGACGTACTAACAGG-3′)-P12-5′r (5′-CAGGTACACTTGTTTAGAGATGAAATGTGGTTTGAACTCC-3′) and P12-3′f (5′-TCAATATCATCTTCTGTCGATGGAGAGGGCTGTTTGTGTA)-P12-3′r (5′-GATCTACCCCCATTTGAAGC-3′) were used to amplify 5′ and 3′ flanking regions of the PKS12 ORF, and a nested primer pair (NP12-5′f [5′-CATCATCAATTCGTTTGC-3′] and NP12-3′r [5′-GTGGCAGATCGTAATCCT-3′]) was used for the fusion product (underlined sequences are homologous to the nucleotide sequences of the primers HygB-f′ and HygB-r, as the primers G1-5′r and G1-3′f for deletion of Gip1). The PCR conditions in which the nested primers were used were denaturation for 3 min at 96°C; 30 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 60°C, and 4 min at 72°C; extension for 10 min at 72°C; and storage at 4°C. Following phenol extraction and ethanol precipitation, the final PCR products were mixed with fungal protoplasts for use in transformation as previously described (25).

Outcross and virulence test.

A sexual cross (24) was made by placing mycelial agar blocks containing a Z3639 derivative with a mat1-1 deletion (T39ΔM1-3) on carrot agar plates and incubating them for 7 days at 25°C. Conidial suspensions (105 conidia/ml) of mutants were added to the T39ΔM1-3 mycelia that grew, and the plates were incubated for an additional 10 to 14 days. Each outcross was performed in 20 carrot agar plates. At least 50 perithecia were arbitrarily selected from each cross, and two ascospores were isolated from each perithecium selected for genetic analysis. To test virulence, conidia were harvested from strains grown on carrot agar plates for 2 weeks at 25°C and were suspended in sterile water at a concentration of 1 × 105 conidia/ml. Each conidial suspension was sprayed onto the heads of barley plants at early anthesis. The plants were incubated for 2 days in a growth chamber at 25°C with 100% relative humidity and were then transferred to a greenhouse. Head blight symptoms appeared 1 week after inoculation.

Complementation analyses.

An intact copy of the PKS12 or Gip1 gene used for complementation analyses was obtained by PCR performed with genomic DNA from strain Z03643 as the template. Primer pairs G43P12-f (5′-CTTCAGTCCTTGGGAACGACCTTGC-3′)-G43P12-r (5′-CCCCATTTGAAGCTGAACTACGACGC-3′) and G43G1-f (5′-GGCATTGAGACTGGAATAGAATCGTGGCT-3′)-G43G1-r (5′-GTGGACCACGTACGAACCTACCGCAA-3′) amplified an 8.8-kb PKS12 region and a 5.0-kb Gip1 region, respectively; the former region included 1.0 kb of the 5′ flanking sequences and 1.3 kb of the 3′ flanking sequences, and the latter region contained 1.5 kb of the 5′ flanking sequences and 1.3 kb of the 3′ flanking sequences. For fungal transformation, about 5 μg of the final PCR product was incorporated directly into fungal protoplasts along with vector pII99 carrying the Geneticin resistance gene (gen) as a fungal selectable marker (24).

Aurofusarin analysis by HPLC.

Aurofusarin was prepared in our laboratory as previously described (9). Briefly, dried PDA cultures (90 g) of G. zeae SCKO4 were ground in a blender and boiled with 300 ml of chloroform. The chloroform extract was concentrated to dryness and then dissolved in 50 ml of warm phenol to which 50 ml of ethanol was added. After the solvents were filtered through Whatman no. 1 filter paper (Whatman Inc., Clifton, N.J.), 170 mg of aurofusarin was obtained as a deep red powder. To analyze aurofusarin production, dried PDA cultures were extracted with chloroform and analyzed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with a Waters 510 HPLC system equipped with a diode array detector and a Luna C18 reverse-phase column (150 cm by 4.6 mm; particle size, 5 μm; Luna, Torrance, Calif.). The HPLC analysis was performed with a linear elution gradient of 50 to 100% methanol at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. The analysis began with 50% methanol, and then the methanol concentration was increased to 100% within 12 min and was then kept constant for an additional 12 min. The detection wavelength was 360 nm.

RESULTS

Phenotype of REMI mutant S4B3076.

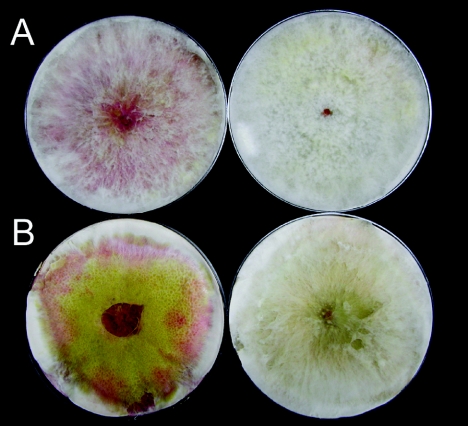

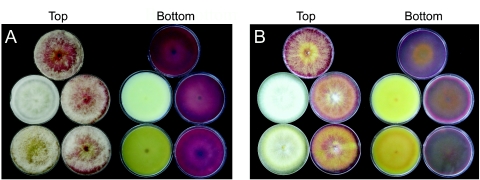

Mutant S4B3076 did not produce pigments but was similar to its wild-type progenitor, SCKO4, in mycelial growth, conidiation, and perithecium formation. Mycelia of the wild-type strain usually began to produce pigment on PDA 4 to 5 days after inoculation, eventually turning carmine red. The mycelia of the mutant remained milky white on plates even after 5 weeks, although the undersurfaces of the cultures turned yellow (Fig. 1A). The mutant phenotype was more apparent on carrot agar because the wild-type strain was more pigmented (Fig. 1B). S4B3076 could cause head blight symptoms on whole barley plants that were typical and similar to the symptoms caused by the wild-type strain (Fig. 2).

FIG. 1.

Mycelial growth of the wild-type progenitor SCKO4 (left side) and the REMI mutant S4B3076 (right side) on PDA (A) and carrot agar (B).

FIG. 2.

Virulence of S4B3076 on barley: symptoms caused by wild-type strain SCKO4 (left side) and by S4B3076 (right side).

Genetic analysis of the tagged mutation in S4B3076.

We crossed S4B3076 (hygBR aur−) and Z-RE1 (hygBR aur−) with T39ΔM1-3 (hygBS aur+). There was no recombination between hygB and aur in the progeny from either cross, and the hygB and aur phenotypes segregated at a 1:1 ratio (the ratios of hygBR aur− to hygBS aur+ were 55:60 and 51:46 in the two crosses, respectively). Thus, the aur− mutation in these strains was linked to the insertion site for the hygB gene.

Molecular characterization of S4B3076.

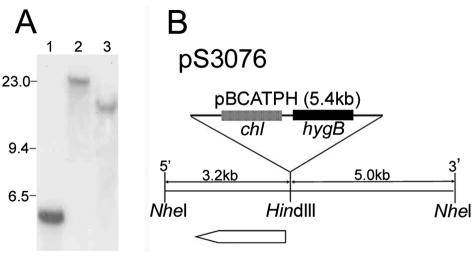

We hybridized a blot of S4B3076 genomic DNA digested with HindIII with the entire REMI vector, pBCATPH, and identified a single ∼5.4-kb fragment, which is the size of pBCATPH. Digestion of the genomic DNA with BglII and NheI, for which there are no restriction sites in the vector, resulted in hybridization of the probe to single fragments that were larger than the vector (>20 and ∼13 kb, respectively) (Fig. 3A). These hybridization patterns are consistent with integration of a single copy of the vector at a HindIII site in the S4B3076 genome.

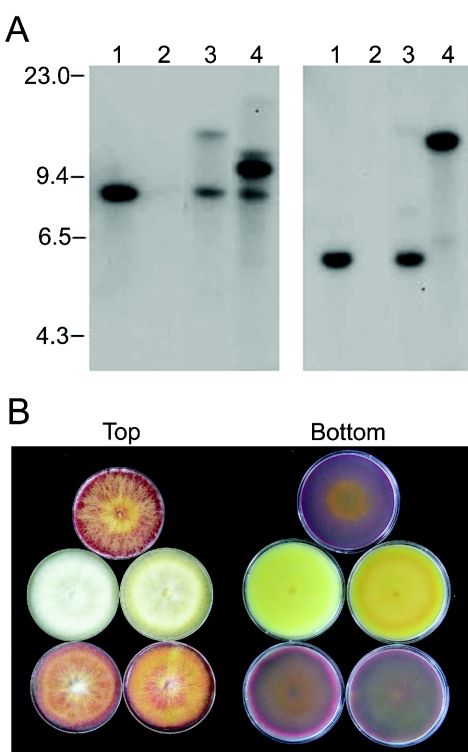

FIG. 3.

Molecular analysis of the vector insertion in the S4B3076 genome. (A) Genomic DNA of S4B3076 was digested with HindIII (lane 1), BglII (lane 2), or NheI (lane 3), and a blot containing the DNAs was hybridized with pBCATPH. The sizes of HindIII-digested phage λ DNA fragments (in kilobases) are indicated on the left. (B) Molecular structure of the plasmid (pS3076) recovered from NheI-digested and self-ligated genomic DNA of S4B3076. The ORF closest to the vector insertion point is indicated by the open arrow.

DNA flanking the vector insertion site in S4B3076 was recovered by plasmid rescue (28). Genomic DNA of S4B3076 was digested with NheI, purified by phenol extraction and ethanol precipitation, self-ligated, and transformed into E. coli DH10B cells. A 13.6-kb NheI fragment was recovered and designated pS3076. This fragment contained 3.2 kb of genomic DNA 5′ of the vector insertion site and 5.0 kb of genomic DNA 3′ of the insertion site (Fig. 3B). A 2,034-bp ORF, designated Gip1, began 38 bp from the insertion site in the 3′ direction. The putative Gip1 protein product had high sequence similarity to fungal laccases, exhibiting 43% amino acid identity to the A. fumigatus abr2 product (40) (GenBank accession no. AF104823) and 40% identity to the A. nidulans yA product (1) (GenBank accession no. X52552).

NheI-linearized pS3076 was transformed into wild-type strains SCKO4 and Z03643 to recreate the original mutation in these strains. DNA gel blot analysis identified several hygBR transformants carrying the same vector insertion as S4B3076, which resulted from double crossover between the genomic DNA recovered from pS3076 and the homologous region in the genomes of these wild-type strains. Like S4B3076, all of these transformants were aur−, while transformants carrying the vector sequence at ectopic locations in the genome normally were pigmented.

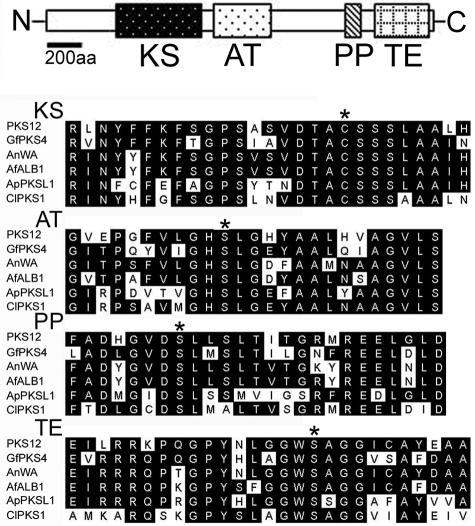

Structural organization of the putative PKS gene cluster.

The vector insertion site in the S4B3076 genome was in contig 1.116 of the F. graminearum genome database. BLAST analysis of more than 30 kb of the contig revealed several other ORFs near Gip1, including one encoding a putative PKS identified as PKS12 (21). PKS12 should have produced a 6.4-kb transcript after five putative introns were spliced. This sequence had high similarity to the fungal type I PKSs responsible for fungal nonmelanin pigments, including the red pigment bikaverin of G. fujikuroi (26) (GenBank accession no. AJ278141) and the conidial pigments of A. nidulans (31) and A. fumigatus (40). The four conserved enzymatic motifs found in the G. fujikuroi pks4 product and other nonreducing PKSs also were present in the PKS12 product in the same order (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Molecular structure of the PKS12 gene, which encodes a PKS involved in aurofusarin production in G. zeae. The map at the top shows the organization of conserved enzymatic domains within the putative PKS12 protein. N, N terminus; KS, ketoacyl synthase; AT, acyltransferase; PP, phosphopantetheine attachment site; TE, thioesterase; C, C terminus; aa, amino acids. The alignment at the bottom is an amino acid alignment of the four enzymatic domains encoded by G. zeae PKS12 with the domains encoded by other fungal nonreducing PKS genes. Conserved amino acids are indicated by a black background. Asterisks indicate the identified or proposed active site of each domain, as follows: for ketoacyl synthase, the acyl binding cysteine residue; for acyltransferase, the pantetheine-binding serine residue; for the phosphopantetheine attachment site, the phosphopantetheine-binding serine residue; and for thioesterase, the serine residue involved in release of the polyketide chain from a PKS enzyme. Abbreviations (accession numbers): GfPKS4, G. fujikuroi PKS4 (AJ278141); AnWA, A. nidulans WA (X65866); AfALB1, A. fumigatus ALB1 (X65866); ApPKSL1, A. parasiticus PKSL1 (L42765); ClPKS1, Colletotrichum lagenarium PKS1 (D83643).

Analysis of Gip1 transcript.

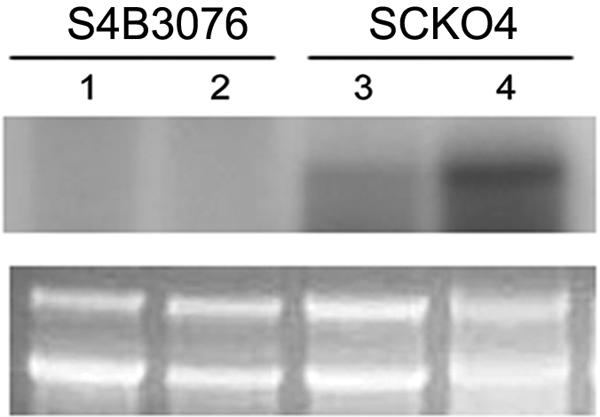

The wild-type and S4B3076 strains were grown on carrot agar for 5 days, and total RNA was extracted. RNA blots were hybridized with the entire Gip1 sequence. In the wild-type strain, the Gip1 transcript was detected in 4- and 5-day-old cultures, but it was not detected in S4B3076 at these times (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

RNA gel blot of the S4B3076 mutant and its wild-type progenitor, SCKO4, grown on carrot medium, which was hybridized with the 32P-labeled Gip1 probe. Lanes 1 and 3, 4-day-old cultures; lanes 2 and 4, 5-day-old cultures. The ethidium bromide-stained agarose gel prior to blotting is beneath the gel showing hybridization.

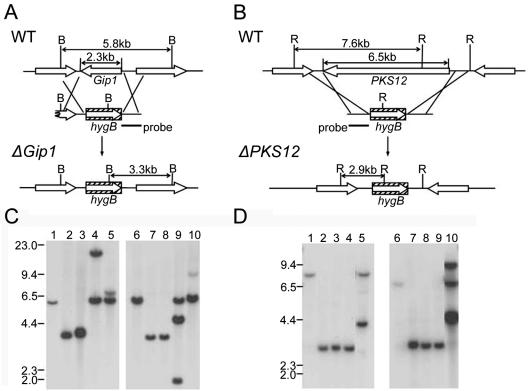

Targeted deletions of PKS12 and Gip1 in G. zeae.

We deleted PKS12 and Gip1 from G. zeae wild-type strains SCKO4 and Z03643. For Gip1, the entire ORF was replaced with the fungal selectable marker hygB by using a PCR fragment carrying both the 5′ and 3′ regions of the Gip1 ORF fused to hygB (Fig. 6A). For PKS12, 6.5 kb of the ORF region of the PKS12 gene was replaced with the hygB gene cassette by using a fusion PCR product (Fig. 6B). Integration of the fusion PCR products via double crossover resulted in transgenic strains of each wild-type strain, in which either Gip1 or PKS12 was deleted (Fig. 6C and D).

FIG. 6.

Deletion of Gip1 or PKS12 from the genomes of wild-type G. zeae strains Z03643 and SCKO4. (A and B) Deletion strategies. WT, genomic DNA of wild-type strain SCKO4; ΔGip1, genomic DNA of the strain with Gip1 deleted; ΔPKS12, genomic DNA of the strain with PKS12 deleted; B, BamHI; R, EcoRI; hygB, hygromycin B resistance gene. Putative ORFs near Gip1 or PKS12 are indicated by arrows. The probes used for blot hybridization are indicated by bars. (C and D) Gel blots of genomic DNAs from Gip1 and PKS12 deletion strains digested with BamHI and EcoRI, respectively. (C) Lane 1, SCKO4; lanes 2 and 3, derivatives of SCKO4 with Gip1 deleted (Tsg1-1 and Tsg1-3, respectively); lanes 4 and 5, transformants that carried the transforming vector at an ectopic site (Tsg1-2 and Tsg1-5, respectively); lane 6, Z03643; lanes 7 and 8, derivatives of Z03643 with Gip1 deleted (Tzg1-3 and Tzg1-5, respectively); lanes 9 and 10, transformants that carried the transforming vector at an ectopic site (Tzg1-1 and Tzg1-2, respectively). (D) Lane 1, SCKO4; lanes 2 to 4, derivatives of SCKO4 with PKS12 deleted (Tsp12-2, Tsp12-3, and Tsp12-6, respectively); lane 5, transformant Tsp12-10, which carried the transforming vector at an ectopic site; lane 6, Z03643; lanes 7 to 9, derivatives of Z03643 with PKS12 deleted (Tzp12-4, Tzp12-5, and Tzp12-9, respectively); lane 10, transformant Tzp12-8, which carried the transforming vector at an ectopic site. The sizes of standards (in kilobases) are indicated on the left.

Genomic DNAs of the Gip1 deletion strains derived from SCKO4 and Z03643 carried a single 3.3-kb hybridizing band instead of the 5.8-kb band found in the wild-type strains, suggesting that a 2.3-kb region containing the Gip1 ORF had been deleted and replaced with the hygB gene (Fig. 6A). The PKS12 deletion strains derived from SCKO4 and Z03643 carried a 6.5-kb deletion in the PKS12 ORF, which was replaced with the hygB gene (Fig. 6D). Neither the strains with Gip1 deleted nor the strains with PKS12 deleted produced aurofusarin when they were grown on PDA, but transgenic strains carrying the transforming DNA at ectopic positions had red, wild-type pigmentation (Fig. 7). The pigmentation patterns of the mutants depended on the strain and on the genes deleted. The ΔPKS12 strains had more severely altered pigmentation than the ΔGip1 strains, and in general, the color of the ΔPKS12 strains was usually lighter than the color of the ΔGip1 strains. The ΔPKS12 and ΔGip1 derivatives of Z03643 also were also more yellowish than the corresponding mutants with the SCKO4 background.

FIG. 7.

Pigmentation of derivatives of G. zeae SCK04 (A) and Z03643 (B) with Gip1 and PKS12 deleted on PDA plates. In each panel, top views of aerial mycelia grown on the plates are on the left, and the undersurfaces of the corresponding plates are shown on the right. (A) Top plates, SCKO4; middle left plates, strain Tsp12-2 with PKS12 deleted; middle right plates, transformant carrying an ectopic vector integration (Tsp12-10); bottom left plates, strain Tsg1-1 with Gip1 deleted; bottom right plates, transformant carrying an ectopic vector integration (Tsg1-2). (B) Top plates, Z03643; middle left plates, strain Tzp12-4 with PKS12 deleted; middle right plates, transformant carrying an ectopic vector integration (Tzp12-8); bottom left plates, mutant Tzg1-3 with Gip1 deleted; bottom right plates, transformant carrying an ectopic vector integration (Tzg1-1).

Complementation analyses.

An intact copy of both genes amplified from the Z03643 strain was introduced into the mutant genomes by using a cotransformation procedure to determine whether the PKS12 or Gip1 gene could complement the aurofusarin-deficient phenotype in a ΔPKS12 or ΔGip1 strain. Of 15 Geneticin-resistant transformants derived from Tzp12-4, the Z03643 ΔPKS12 recipient, 5 produced as much aurofusarin as the wild-type strain produced. Similarly, seven aurofusarin-producing transformants were recovered from 13 transformants of Tzg1-3, the Z03643 ΔGip1 recipient. All of the normally pigmented transformants examined had at least one copy of the intact PKS12 or Gip1 ORF in the genome (Fig. 8).

FIG. 8.

Complementation of pigmentation mutation in ΔPKS12 and ΔGip1 mutants. (A) Gel blot of genomic DNAs from the normally pigmented transformants derived from the ΔPKS12 or ΔGip1 strains by using an intact copy of the corresponding gene. Genomic DNAs of the ΔPKS12 and ΔGip1 transformants were digested with EcoRI and BamHI, respectively. A 6.5-kb fragment of the PKS12 ORF and a 2.2-kb fragment of the Gip1 ORF were used as probes. (Left gel) Lane 1, wild-type strain Z03643; lane 2, Tzp12-4, a ΔPKS12 recipient strain; lanes 3 and 4, normally pigmented transformants of Tzp12-4 (Rp12-4-1 and Rp12-4-4, respectively). (Right gel) Lane 1, wild-type strain Z03643; lane 2, Tzg1-3, a ΔGip1 recipient strain; lanes 3 and 4, normally pigmented transformants of Tzg1-3 (Rg1-3-2 and Rg1-3-3, respectively). (B) Pigmentation of the transformants examined by DNA gel blot analysis. Top plates, Z03643; middle left plates, Tzp12-4; middle right plates, Tzg1-3; bottom right plates, Rp12-4-1; bottom left plates, Rg1-3-2.

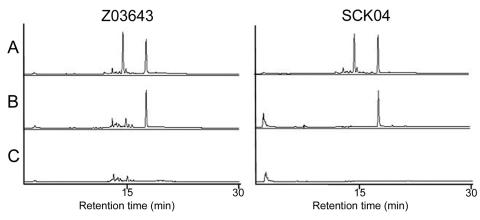

Aurofusarin analysis by HPLC.

Aurofusarin was detected in both wild-type strains (Fig. 9A). A major peak with a retention time of 17.1 min was also present, in addition to a peak for aurofusarin. Neither aurofusarin nor the second compound was detected in the ΔPKS12 strains, but only aurofusarin was missing in the ΔGip1 strains. Thus, the PKS12 translation product may participate in the biosynthesis of the second compound in addition to the biosynthesis of aurofusarin (Fig. 9B and C).

FIG. 9.

HPLC chromatograms of aurofusarin in wild-type G. zeae strains Z03643 and SCKO4 and strains with PKS12 and Gip1 deleted. (A) Wild type; (B) mutant with laccase gene (Gip1) deleted; (C) mutant with PKS gene (PKS12) deleted. The retention time of aurofusarin is 14.5 min.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we isolated genes encoding a type I PKS (PKS12) and a putative laccase (Gip1) that are required for aurofusarin biosynthesis by G. zeae. Although G. zeae and F. culmorum have been reported to produce both aurofusarin and rubrofusarin (2, 38), we detected only aurofusarin by HPLC analysis of G. zeae culture extracts.

Fusarium species produce many naphthoquinone metabolites (2, 17, 32, 36). These compounds have diverse biological activities, including phytotoxicity, antimicrobial activity, insecticidal activity, and anticarcinogenic activity (32). Aurofusarin can reduce the nutritional quality of quail eggs (6, 7), but the general antibiotic and phytotoxic activities of aurofusarin have not been extensively studied. Moreover, the biological role(s) of aurofusarin in G. zeae has not been determined. The phenotype of the aurofusarin-deficient REMI mutant suggests that aurofusarin biosynthesis is not required for most cultural characteristics of G. zeae or for the virulence of this organism for barley. However, further investigations are needed to determine if aurofusarin is involved in other traits of G. zeae (e.g., development and survival) in which other fungal pigments are known to have a role (23, 31, 39, 41).

The tagged mutation in REMI mutant S4B3076 led to the identification of the two genes studied here (PKS12 and Gip1). Targeted deletion of PKS12 and Gip1 followed by complementation analyses of the mutants confirmed that these genes participate in the biosynthesis of aurofusarin by G. zeae. The chemical structure of aurofusarin suggests that it is an unreduced polyketide and that it may be synthesized through condensation steps catalyzed by a nonreducing PKS, followed by additional enzymatic steps, such as methylation and oxidation. A recent phylogenetic analysis of the 16 G. zeae PKS genes identified the PKS12 gene as a gene that encodes a nonreducing PKS (21). Thus, aurofusarin probably is synthesized in G. zeae in a manner similar to the manner used for synthesis of polyketide pigments in other filamentous fungi.

The presence of Gip1, an ortholog of the laccase gene (abr2) required for the synthesis of blue-green conidial pigments in A. fumigatus, near a PKS-encoding gene in G. zeae suggests that these two laccase proteins have functionally similar roles in the polyketide pigment pathway (40). The abr2 protein of A. fumigatus probably oxidizes an intermediate(s) in the conidial pigment pathway. This pigment pathway appears to be similar to the dihydroxynaphthalene-melanin pathway because two additional genes that encode proteins common in fungal melanin biosynthesis, hydroxynaphthalene reductase and scytalone dehydratase, are present in the A. fumigatus cluster (23, 40). The absence of orthologs of the two melanin genes in the 30-kb region in which PKS12 and Gip1 are located suggests that the aurofusarin biosynthetic pathway is not similar to the biosynthetic pathways for the conidial pigments in A. fumigatus or to the dihydroxynaphthalene-melanin pathway of many brown and black fungi.

The functional requirement for Gip1 in aurofusarin biosynthesis in G. zeae indicates that there is an oxidation step(s) catalyzed by Gip1 in the biosynthetic pathway. The dark pigmentation of the perithecia in the aur− strains examined is consistent with the hypothesis that aurofusarin biosynthesis is independent of melanin biosynthesis. However, it is not clear whether the dark or black perithecial pigment in G. zeae is melanin, since no melanin-type PKS gene has been identified in the F. graminearum genome (21) and no mutant for perithecial pigmentation was found in 5,000 REMI transformants of the SCKO4 strain.

The second major compound detected along with aurofusarin probably is biosynthetically related to aurofusarin since it is unusual for a PKS to participate in the synthesis of more than one compound. This compound might be a precursor of aurofusarin or a shunt product derived from the aurofusarin biosynthetic pathway. Since the ΔGip1 strains produced this compound, PKS12 is upstream of Gip1 in the aurofusarin biosynthetic pathway. The yellowish color that remained in both ΔGip1 strains could have resulted from an intermediate(s) that accumulated due to disruption of Gip1; i.e., a substrate(s) of the Gip1-encoded protein may be yellow (Fig. 7). It is not clear if the second major compound is a substrate of the Gip1-encoded protein, since this compound did not accumulate in the ΔGip1 strains. The light yellow color observed in the Z03643 ΔPKS12 strain could have resulted from an additional yellow pigment(s) produced only by Z03643 that is not related to the aurofusarin pathway.

The ΔPKS12 strains described here should be useful for large-scale production of mycotoxins such as deoxynivalenol and zearalenone because of the absence of pigments in these strains (12). As aurofusarin complicates the purification of these mycotoxins, its absence should simplify the purification steps.

In conclusion, this study is significant both fundamentally and practically. It provided important information for further investigation of aurofusarin, which is both a toxic metabolite and an undesirable cometabolite of G. zeae, as well as for understanding naphthoquinone biosynthesis in other fungi. In addition, the pigment mutants generated in this study should be useful for exploring the specific role(s) of aurofusarin biosynthesis in G. zeae. Further functional studies of the other ORFs near PKS12 and Gip1 are needed to determine if this region contains a cluster of genes that are required for aurofusarin biosynthesis in G. zeae.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grant CG 1413 from the Crop Functional Genomics Center of the 21st Century Frontier Research Program, funded by the Korean Ministry of Science and Technology and the Rural Development Administration of the Republic of Korea, and by grant R01-2003-000-10208-0 from the Korean Science and Engineering Foundation. J.-E.K. and K.-H.H. were supported by graduate and postdoctoral fellowships, respectively, from the Korean Ministry of Education through the Brain Korea 21 project.

We thank R. L. Bowden, Plant Science and Entomology Research Unit, United States Department of Agriculture Agricultural Research Service, Manhattan, Kans., for providing G. zeae strain Z03643.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aramayo, R., and W. E. Timberlake. 1990. Sequence and molecular structure of the Aspergillus nidulans yA (laccase I) gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 18:3415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ashley, J. N., B. C. Hobbs, and H. Raistrick. 1937. Studies in the biochemistry of micro-organisms. LIII. The crystalline coloring matters of Fusarium culmorum (W. G. Smith) Sacc. and related forms. Biochem. J. 31:385-397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bowden, R. L., and J. F. Leslie. 1999. Sexual recombination in Gibberella zeae. Phytopathology 89:182-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Correll, J. C., C. J. R. Klittich, and J. F. Leslie. 1987. Nitrate nonutilizing mutants and their use in vegetative compatibility tests. Phytopathology 77:1640-1646. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Couch, R. D., and G. M. Gaucher. 2004. Rational elimination of Aspergillus terreus sulochrin production. J. Biotechnol. 108:171-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dvorska, J. E., P. F. Surai, B. K. Speake, and N. H. C. Sparks. 2001. Effect of the mycotoxin aurofusarin on the antioxidant composition and fatty acid profile of quail eggs. Br. Poult. Sci. 42:643-649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dvorska, J. E., and P. F. Surai. 2004. Protective effect of modified glucomannans against changes in antioxidant systems of quail egg and embryo due to aurofusarin consumption. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 17:434-440. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Graham, J. G., H. J. Zhang, S. L. Pendland, B. D. Santarsiero, A. D. Mesecar, F. Cabieses, and N. R. Farnsworth. 2004. Antimycobacterial naphthopyrones from Senna obliqua. J. Nat. Prod. 67:225-227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gray, J. S., G. C. J. Martin, and W. Rigby. 1967. Aurofusarin. J. Chem. Soc. 1967(C):2580-2587.

- 10.Graziani, S., C. Vasnier, and M. Daboussi. 2004. Novel polyketide synthase from Nectria haematococca. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:2984-2988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Han, K.-H., J.-A. Seo, and J.-H. Yu. 2004. A putative G protein-coupled receptor negatively controls sexual development in Aspergillus nidulans. Mol. Microbiol. 51:1333-1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hidy, P. H., R. S. Baldwin, R. L. Greasham, C. L. Keith, and J. R. McMullen. 1977. Zearalenone and some derivatives: production and biological activities. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 22:59-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hopwood, D. A., and D. H. Sherman. 1990. Molecular genetics of polyketides and its comparison to fatty acid biosynthesis. Annu. Rev. Genet. 24:37-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hutchinson, C. R. 1999. Microbial polyketide synthases: more and more prolific. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:3336-3338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jahn, B., F. Boukhallouk, J. Lotz, K. Langfelder, G. Wanner, and A. A. Brakhage. 2000. Interaction of human phagocytes with pigmentless Aspergillus conidia. Infect. Immun. 68:3736-3739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kereyi, Z., K. Zeller, L. Hornok, and J. F. Leslie. 1999. Molecular standardization of mating type terminology in the Gibberella fujikuroi species complex. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:4071-4076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kimura, Y., A. Shimada, H. Nakajima, and T. Hamasaki. 1988. Structures of naphthoquinones produced by the fungus, Fusarium sp., and their biological activity toward pollen germination. Agric. Biol. Chem. 52:1253-1259. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kitanaka, S., T. Nakayama, T. Shibano, E. Ohkoshi, and M. Takido. 1998. Antiallergic agent from natural sources. Structures and inhibitory effect of histamine release of naphthopyrone glycosides from seeds of Cassia obtusifolia L. Chem. Pharm. Bull. (Tokyo) 46:1650-1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klittich, C. J. R., and J. F. Leslie. 1988. Nitrate reduction mutants of Fusarium moniliforme (Gibberella fujikuroi). Genetics 118:417-423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kotik, A. N., and V. A. Trufanova. 1998. Detection of naphthoquinone fusariotoxin aurofusarin in wheat. Mikol. Fitopatol. 32:58-61. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kroken, S., N. L., Glass, J. W. Taylor, O. C. Yoder, and B. G. Turgeon. 2003. Phylogenomic analysis of type I polyketide synthase genes in pathogenic and saprobic ascomycetes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:15670-15675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Langfelder, K., B. Jahn, H. Gehringer, A. Schmidt, G. Wanner, and A. A. Brakhage. 1998. Identification of a polyketide synthase gene (pksP) of Aspergillus fumigatus involved in conidial pigment biosynthesis and virulence. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 187:79-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Langfelder, K., M. Streibel, B. Jahn, G. Hasse, and A. A. Brakhage. 2003. Biosynthesis of fungal melanins and their importance for human pathogenic fungi. Fungal Genet. Biol. 38:143-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee, J., T. Lee, Y. W. Lee, S. H. Yun, and B. G. Turgeon. 2003. Shifting fungal reproductive mode by manipulation of mating type genes: obligatory heterothallism of Gibberella zeae. Mol. Microbiol. 50:145-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee, T., Y.-K. Han, K.-H. Kim, S.-H. Yun, and Y.-W. Lee. 2002. Tri13 and Tri7 determine deoxynivalenol- and nivalenol-producing chemotypes of Gibberella zeae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:2148-2154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Linnemannstons, P., J. Schulte, M. D. Prado, R. H. Proctor, J. Avalos, and B. Tudzynski. 2002. The polyketide synthase gene pks4 from Gibberella fujikuroi encodes a key enzyme in the biosynthesis of the red pigment bikaverin. Fungal Genet. Biol. 37:134-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu, Z., and N. C. Mishra. 1995. A single-tube method for plasmid mini-prep from large numbers of clones for direct screening by size or restriction digestion. BioTechniques 18:214-217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lu, S. W., L. Lyngholm, G. Yang, C. Bronson, O. C. Yoder, and B. G. Turgeon. 1994. Tagged mutations at the Tox1 locus of Cochliobolus heterostrophus using restriction enzyme-mediated integration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:12649-12653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Macias, M., M. Ulloa, A. Gamboa, and R. Mata. 2000. Phytotoxic compounds from the new coprophilous fungus from Guanomyces polythrix. J. Nat. Prod. 63:757-761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marasas, W. F. O., P. E. Nelson, and T. A. Toussoun. 1984. Toxigenic Fusarium species; identity and mycotoxicology. The Pennsylvania State University Press, University Park.

- 31.Mayorga, M. E., and W. E. Timberlake. 1992. The developmentally regulated Aspergillus nidulans wA gene encodes a polyketide homologous to polyketide and fatty acid synthases. Mol. Gen. Genet. 235:205-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Medentsev, A. G., and V. K. Akimenko. 1998. Naphthoquinone metabolites of the fungi. Phytochemistry 47:935-959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nelson, P. E., T. A. Toussoun, and W. F. O. Marasas. 1983. Fusarium species—an illustrated manual for identification. The Pennsylvania State University Press, University Park.

- 34.O'Donnell, K., H. C. Kistler, B. K. Tacke, and H. H. Casper. 2000. Gene genealogies reveal global phylogeographic structure and reproductive isolation among lineages of Fusarium graminearum, the fungus causing wheat scab. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:7905-7910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 36.Steyn, P. S., P. L. Wessels, and W. F. O. Marasas. 1979. Pigments from Fusarium moniliforme Sheldon. Structure and 13C nuclear magnetic resonance assignment of an azaanthraquinone and three naphthoquinones. Tetrahedron 35:1551-1555. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takano, Y., Y. Kubo, K. Shimizu, K. Mise, T. Okubo, and I. Furusawa. 1995. Structural analysis of PKS1, a polyketide synthase gene involved in melanin biosynthesis in Colletotrichum lagenarium. Mol. Gen. Genet. 249:162-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tanaka, H., and T. Tamura. 1962. The chemical constitution of rubrofusarin, a pigment from Fusarium graminearum. Part. I. The zinc dust distillation of rubrofusarin and methylxanthones. Agric. Biol. Chem. 26:767-770. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tsai, H.-F., Y. C. Chang, R. G. Washburn, M. H. Wheeler, and K. J. Kwon-Chung. 1998. The developmentally regulated alb1 gene of Aspergillus fumigatus: its role in modulation of conidial morphology and virulence. J. Bacteriol. 180:3031-3038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tsai, H.-F., M. H. Wheeler, Y. C. Chang, and K. J. Kwon-Chung. 1999. A developmentally regulated gene cluster involved in conidial pigment biosynthesis in Aspergillus fumigatus. J. Bacteriol. 181:6469-6477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wheeler, M. H., and A. A. Bell. 1987. Melanins and their importance in pathogenic fungi. Curr. Top. Med. Mycol. 2:338-387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yun, S.-H. 1998. Molecular genetics and manipulation of pathogenicity and mating determinants in Mycosphaerella zeae-maydis and Cochliobolus heterostrophus. Ph.D. thesis. Cornell University, Ithaca, N.Y.

- 43.Yun, S.-H., B. G. Turgeon, and O. C. Yoder. 1998. REMI-induced mutants of Mycosphaerella zeae-maydis lacking the polyketide PM-toxin are deficient in pathogenesis to corn. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 52:53-66. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yun, S.-H., T. Arie, I. Kaneko, O. C. Yoder, and B. G. Turgeon. 2000. Molecular organization of mating type loci in heterothallic, homothallic, and asexual Gibberella/Fusarium species. Fungal Genet. Biol. 31:7-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]