Abstract

The production of N2 gas via anammox was investigated in sediment slurries at in situ NO2− concentrations in the presence and absence of NO3−. With single enrichment above 10 μM 14NO2− or 14NO3− and 15NH4+, anammox activity was always linear (P < 0.05), in agreement with previous findings. In contrast, anammox exhibited a range of activity below 10 μM NO2− or NO3−, including an elevated response at lower concentrations. With 100 μM NO3−, no significant transient accumulation of NO2− could be measured, and the starting concentration of NO2− could therefore be regulated. With dual enrichment (1 to 20 μM NO2− plus 100 μM NO3−), there was a pronounced nonlinear response in anammox activity. Maximal activity occurred between 2 and 5 μM NO2−, but the amplitude of this peak varied across the study (November 2003 to June 2004). Anammox accounted for as much as 82% of the NO2− added at 1 μM in November 2003 but only for 15% in May 2004 and for 26 and 5% of the NO2− added at 5 μM for these two months, respectively. Decreasing the concentration of NO3− but holding NO2− at 5 μM decreased the significance of anammox as a sink for NO2−. The behavior of anammox was explored by use of a simple anammox-denitrification model, and the concept of a biphasic system for anammox in estuarine sediments is proposed. Overall, anammox is likely to be regulated by the availability of NO3− and NO2− and the relative size or activity of the anammox population.

Recently, it has been demonstrated that in both aquatic sediments and anoxic water basins denitrification is not the only pathway for N2 formation (3, 8, 19, 22). Anaerobic ammonium oxidation (anammox) can couple the reduction of NO2− to the oxidation of NH4+, producing N2 gas, and hence act as an additional pathway for the removal of N from aquatic ecosystems, yet what regulates the significance of anammox for N removal in aquatic systems is largely unknown (4). Given that N is often limiting for primary production in aquatic ecosystems, further understanding of this novel shunt in the N cycle is essential.

Research using microelectrodes and measurements of solute exchange, for example, O2, NO3−, and NH4+, has established that the concentrations of solutes in sediment pore water and overlying water are at a steady state (11, 13, 14). Nitrate concentrations can reach 1 mM in the overlying water of hypernutrified estuaries and can still be present in the top 0 to 1 cm of sediment at 400 μM; however, the magnitude of both of these pools is seasonal (6, 9). In contrast, the concentrations of NO2− in both the overlying water and sediment are usually 2 orders of magnitude less than those of NO3− and seldom exceed 5 μM, though in comparison to NO3−, data for NO2− are scarce. Studies using NO2− microsensors, biosensors, or fine-scale porewater extraction methods have indicated that net NO2− production occurs in anaerobic sediment as a result of NO3− reduction (15, 17). In addition, the first stage of nitrification at the aerobic-anaerobic interface produces NO2−, which, depending on the conditions for nitrification and the overall demand for NO2−, may diffuse into the underlying anaerobic layers (5). The critical point is that at a steady state, NO2− and NO3− can coexist in anaerobic sediments at concentrations separated by orders of magnitude.

To date, measurements of anammox in sediments have relied on anaerobic slurries or anaerobic bag incubations enriched with NO3−, NO2−, or both at concentrations higher than those in the environment, especially for NO2− (19, 22). In anaerobic slurries, in the direct presence of NO3−, anammox is reliant on the initial reduction of NO3− to NO2− by the total NO3−-reducing community. Nitrate respiration (NO3−→NO2−) results in NO2− as an actual end product of metabolism which is exported from the cell. In contrast, NO2− is an intermediary of the denitrification (NO3−→NO2−→NO→N2O→N2) and dissimilatory reduction of nitrate to ammonium (NO3−→NO2−→NH4+) pathways. All of this intermediary NO2− may “leak” from the cell into the surrounding environment. The loss of NO2− is in part governed by the kinetics of each respective enzyme, the species of NO3−-reducing bacteria, and the quality of the organic substrate (1, 2). The linear formation of 29N2 from 15NH4+ and 14NO2− in anaerobic slurries suggests that NO2− is nonlimiting for anammox, and hence the pathway of NO2− formation would be irrelevant to the actual significance of anammox, but these observations (19, 22) come from experiments that were not specifically designed to examine the behavior of anammox at representative in situ NO2− concentrations (<10 μM). Even in the presence of NO2− and the absence of NO3−, the anammox community will have to compete against the largely heterotrophic NO3−- and NO2−-reducing community, which will use NO2− just as efficiently in the absence of NO3− (22).

Although we cannot reproduce a steady state in batch sediment slurry experiments, unlike intact sediment cores, the purpose of this study was to investigate the fate of NO2− and the behavior of anammox at representative sediment NO2− concentrations in the presence and absence of NO3−. Here we show that anammox exhibits pronounced nonlinear behavior at concentrations below 10 μM NO2− in the presence of 100 μM NO3−. In addition, a simple anammox-denitrification model and the concept of a biphasic system for anammox in estuarine sediments are proposed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample sites and sediment slurry preparation.

Sediment samples (oxic and suboxic layers from 0 to 2 cm) were collected from the intertidal flats at low tide from an area in the Thames estuary where significant anammox had previously been measured (site 2 [22]), stored in plastic bags, and returned to the laboratory within 1 h. Anaerobic ammonium oxidation was assayed by measuring the production of 29N2 in anaerobic slurries as previously described (22). Sediment slurries were enriched by injection through the septa, using microliter syringes (Hamilton, Bonaduz, Switzerland), with concentrated stocks of 15NH4Cl (120 mM 15NH4Cl [99.3 15N atom%]) (Sigma-Aldrich, Poole, United Kingdom) to give a final concentration of 500 μM 15NH4+ (approximately 60% labeling of the NH4+ pool) and either Na14NO2 or Na14NO3 (stock concentrations of 4 and 93 mM, respectively) (VWR International Ltd., Lutterworth, United Kingdom) to give a range of concentrations (see below). Sediments from this site are capable of reducing NO3− at approximately 100 μM h−1, and an overnight preincubation ensured that all traces of potential oxidants were removed before experimental manipulations commenced (22). All incubations were carried out on rollers in the dark in a constant-temperature room at 15°C. Following incubation, gas samples were collected (1 ml) using a gas-tight syringe (SGE Gastight Luer Lock syringe; Alltech Associates Ltd., Carnforth, Lancashire, United Kingdom) and stored in an inverted water-filled gas-tight vial (12-ml Exetainer; Labco Ltd., High Wycombe, United Kingdom). For determinations of the labeling of the NH4+ pool, pore waters were recovered from both enriched and nonenriched reference slurries by centrifugation of the slurry, filtered (0.2-μm-pore-size Minisart Plus filter; Sartorius UK Ltd.), and frozen (−20°C) until later analysis.

Anammox activity with single NO2− or NO3− enrichment.

For the first set of experiments, slurries were enriched with 15NH4+ and then independently with either 14NO3− or 14NO2− to give final concentrations of 1, 2.5, 5, 8, 10, 12, 16, and 20 μM, incubated overnight, and treated as described above.

Nitrate reduction and nitrite accumulation.

In order to determine the effect of the NO3− enrichment concentration on NO2− accumulation, we enriched prepared sediment slurries with 14NO3− at 100, 200, 400, and 600 μM and sacrificed independent slurries every hour for 4 h. The microbial activity was inhibited by injecting ZnCl2 (500 μl of a 50% [wt/vol] solution) through the septum of the serum bottle, and the pore waters were recovered and treated as described above for later analyses of NO3− and NO2− (see below).

Anammox activity with dual NO2− and NO3− enrichment.

Having established the concentration of NO3− at which NO2− did not transiently accumulate in the slurries (100 μM NO3− [see Results]), we prepared dual-enrichment experiments as outlined above and added isotopes from concentrated stocks to give the following final concentrations, in this order: 15NH4+ at 500 μM; 14NO3− at 100 μM followed by mixing for 5 min on rollers (during which time approximately 8% of the NO3− pool would have turned over); and finally, 14NO2− at 1, 2.5, 5, 8, 10, 12, 16, or 20 μM. Subsequent dual-enrichment experiments were performed with 25, 50, 75, and 100 μM 14NO3− and with 14NO2− at just 5 μM. The slurries were incubated overnight and treated as described above.

Analysis.

All nutrient analyses (NO3−, NO2−, and NH4+) were performed by use of a continuous-flow autoanalyzer (San++; Skalar, Breda, The Netherlands) and standard colorimetric techniques (7). Salinities were measured using a hand-held refractometer. Water contents, specific gravities, and porosities were determined from the dry and wet weights of known volumes of sediment. Samples of the headspace (50 μl) from the gas-tight vials were injected using an autosampler into an elemental analyzer interfaced with a continuous-flow isotope ratio mass spectrometer calibrated with air, and the mass charge ratios for m/z 28, 29, and 30 nitrogen (28N2, 29N2, and 30N2) were measured (Delta Matt Plus; Thermo-Finnigan, Bremen, Germany).

Calculation of total anammox activity.

Assuming that the 15NH4+ pool turns over at the same rate as the ambient 14NH4+ pool, the total anammox N2 production can be calculated from the production of 29N2 and the proportionate 15N labeling of the NH4+ pool, determined by accounting for the difference from nonenriched reference slurries (19, 22). Anammox can be measured by labeling either the electron donor (15NH4+) or acceptor (15NO3− and 15NO2−) pool (19), and we have previously demonstrated a high level of agreement between these two techniques (22). For this study, however, only the NH4+ pool was labeled, and our measures of anammox are therefore expressed relative to total NO3− and NO2− reduction and not total gas formation.

Modeling the behavior of anammox.

A simple model was developed in EcoS (version 3.37, N.E.R.C.; Plymouth Marine Laboratory, Plymouth, United Kingdom) to examine the behavior (shape of response) of anammox in the dual presence of NO2− and NO3− in a slurry system with a mixed population of anammox and denitrifying bacteria. The model is based around the assumption that anammox, as an autotroph, makes up a relatively small proportion (θ) of the total NO3− and NO2− reducer population (<5%) and can only use NO2− as an oxidant, whereas the denitrifying population will use NO3− preferentially but will swap to NO2− when NO3− falls below a certain threshold (22). In addition, for the sake of simplicity, the additional potential source of NO2− for anammox resulting from denitrification was not included (see Results for rationale); hence, as in the above experiments, the mixed population was started with only external sources for both NO2− and NO3−.

The changes over time of NO2− and NO3− concentrations in the pore water, subject to consumption by a bacterial population with the proportion θ of anammox and 1 − θ of denitrifiers, were assumed to be governed by the following equations:

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

where M is the number of bacteria per liter. The rates of consumption of NO2− by denitrifiers as a function of [NO2−] were assumed to be given by the following equations:

|

(3) |

|

(4) |

In these equations, fd and gd are classic Michaelis forms with half-saturation constants kNOx and maximum rates VMxD (μmol N bacterium−1 day−1). The following function acts to block the denitrifier reduction of NO2− when NO3− is available:

|

(5) |

It gives a linear decrease in rate for increasing [NO3−], with no uptake of NO2− occurring when [NO3−] > [NO3−]crit, in this case, 100 μM NO3−. The rate of consumption of NO2− by anammox was modeled as a biphasic process, determined by the following equation:

|

(6) |

where VMA (μmol N bacterium−1 day−1) is a maximal processing rate, and the modifying functions fp and fm, with 0 < fp and fm < 1, are given by the following equations:

|

(7) |

|

(8) |

The function fp yields an optimum rate when [NO2−] = lN, with inhibition for [NO2−] above and below this rate (see Fig. 3). The function fm, which is Michaelis in form, yields a constant reduction rate for NO2− at concentrations more than six times Km. The combination yields a peak of ∼VMA when [NO2−] = lN and smoothly decreases to a proportion, ɛ, of the maximal rate at high NO2− concentrations. We emphasize that it was not the purpose of this modeling exercise to precisely replicate the conditions and dimensions of our experimental slurries, but rather just to explore the overall shape of the anammox activity. While the half-saturation constants for anammox and denitrification are realistic, at 2.5 μM (reference 4 and data reported here) and 15 μM (1), respectively, the total number of bacteria was set to 104 liter−1 and the maximum rate of reaction for anammox and denitrification was set to 10−3 μmol N bacterium−1 day−1.

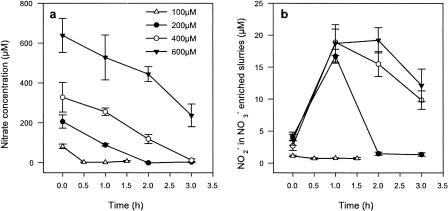

FIG. 3.

(a) Total anammox (AAO) N2 production in the direct presence of 1 to 10 μM 14NO2−, 100 μM 14NO3−, and 500 μM 15NH4+. (b) AAO as a percentage of each NO2− spike. (c and d) Representative ranges of patterns for AAO with NO2− from 1 to 20 μM and 100 μM 14NO3−. (e and f) AAO with 5 μM 14NO2− and decreasing concentrations of 14NO3−. Note that a measurement with 0 μM 14NO3− was not determined in November 2003. Values are means ± 1 SEM (n = 4). The same symbols are used for each respective left and right panel.

RESULTS

Anammox activity with single NO2− or NO3− enrichment.

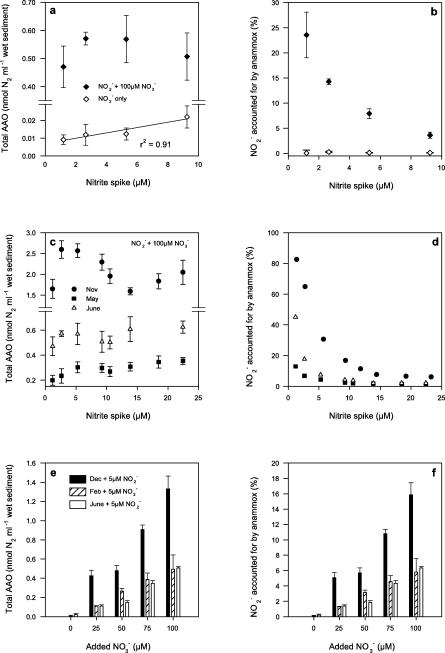

Above 10 μM NO2− or NO3−, anammox activity was always linear (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1). In contrast, anammox exhibited a range of activity below 10 μM NO2− or NO3− (Fig. 1). For example, at concentrations below 10 μM for either NO2− or NO3−, 29N2 production remained constant (Fig. 1a) and, in turn, the percentages of the electron acceptors accounted for by anammox increased to 7 and 4%, respectively (Fig. 1b). Alternatively, the production of 29N2 increased linearly from 2.5 to 20 μM NO2− or NO3−, and the percentage accounted for by anammox remained constant at <2% (Fig. 1c and d). Overall, the single-enrichment activities were highly variable below 10 μM, and on occasion (October and November 2003), several data points supported elevated activities below 5 μM (Fig. 1e and f). In contrast, the heterotrophic NO3−- and NO2−-reducing community accounted for >93 and 96% of the NO2− or NO3−, respectively.

FIG. 1.

(a and c) Production of 29N2 from labeled 15NH4+ oxidation in the direct presence of 14NO2− or 14NO3− in November and December 2003. (b and d) Total anammox N2 production (calculated from 29N2 production) as a percentage of the respective NO2− or NO3− spike. (e and f) Composite of the above NO2− data plus additional NO2− data for October 2003. Values are means ± 1 standard error of the means (SEM) (n = 4).

Nitrate reduction and nitrite accumulation.

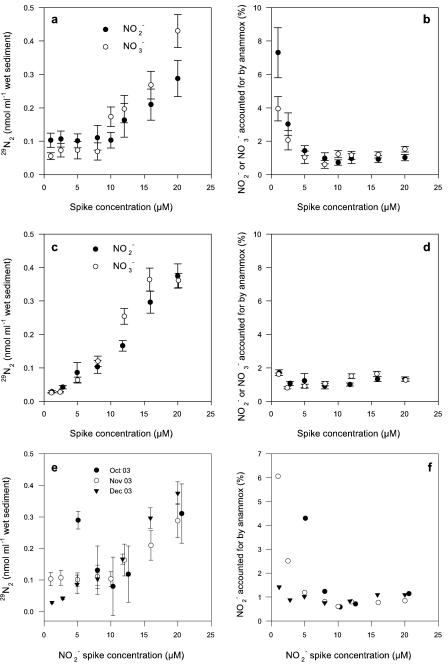

In slurries enriched with 100 μM NO3−, all of the NO3− had been consumed within the first half-hour and no significant transient accumulation of NO2− could be measured (Fig. 2). At 200, 400, and 600 μM NO3−, the slurries exhibited similar rates of NO3− reduction, i.e., 103, 105, and 97 μM h−1, respectively. These data agree with the rate of 85 μM h−1 measured at the same site in the previous year (22). In addition, those samples enriched with 200 μM NO3− and above exhibited a transient accumulation of NO2− of 19 μM after 1 h. Therefore, 100 μM NO3− could, at least during our short dual incubations, satisfy total NO3− reduction and enable the initial availability of NO2− to be regulated.

FIG. 2.

(a) Reduction of NO3− over time in anaerobic sediment slurries at four NO3− enrichment concentrations. (b) Subsequent accumulation and reduction of NO2− over time for each respective NO3− enrichment. Values are means ± 1 SEM (n = 4). The same symbols are used in each panel.

Anammox activity with dual NO2− and NO3− enrichment.

In the dual presence of NO2− (1 to 10 μM) and NO3− (100 μM) there was an even more pronounced nonlinear response in anammox activity, relative to those in the single enrichments (Fig. 3a). In addition, there was a marked increase in overall anammox activity in the dual-enrichment experiments. For example, the anammox activity increased from 0.01 nmol N2 ml−1 wet sediment at 5 μM NO2− without NO3− to 0.6 nmol N2 ml−1 wet sediment with NO3−. In turn, the presence of NO3− increased the percentage of NO2− accounted for by anammox from 0.15 to 8% at 5 μM NO2−. As with the previous single-enrichment experiments, anammox exhibited a range of activities, although they all had a similar shape (Fig. 3c). The maximum anammox activity in the presence of both NO2− and NO3− was measured in November 2003 (2.6 nmol N2 ml−1 wet sediment at 5 μM NO2−), and the lowest, to date, was measured in May 2004 (0.3 nmol N2 ml−1 wet sediment at 5 μM NO2−). In November, anammox accounted for as much as 82% of the NO2− at 1 μM, but it only accounted for 15% in May and between 26 and 5% at 5 μM NO2−, respectively, for these two months (Fig. 3d). Using 5 μM NO2− and 100 μM NO3− as a reference measure for anammox, we show the data collected to date in Table 1, along with some site characteristics.

TABLE 1.

Summary of anammox activities measured under dual enrichment with 5 μM NO2−, 100 μM NO3−, and 500 μM 15NH4− at 15°C from November 2003 to June 2004, with some site water characteristics

| Date | Anammox activity (nmol of N2 ml of wet sediment−1)a | NO3− (μM) | NO2− (μM) | Temperature (°C) | Salinity (psu) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| November 2003 | 2.6 ± 0.17 | 167.14 | 0.86 | 12 | 20 |

| December 2003 | 1.3 ± 0.13 | 562.86 | 2.07 | 10 | 12 |

| February 2004 | 0.5 ± 0.15 | 622.14 | 10.64 | 8 | 4 |

| May 2004 | 0.3 ± 0.04 | 427.29 | 1.23 | 13 | 17 |

| 2 June 2004 | 0.6 ± 0.07 | 409.59 | 0.95 | 17 | 17 |

| 16 June 2004 | 0.6 ± 0.08 | 387.63 | 0.83 | 22 | 20 |

Data are means ± standard errors (n = 4 for each date).

In subsequent experiments, dual enrichment was repeated with 5 μM NO2− and with NO3− from 0 to 100 μM (Fig. 3e and f). Clearly, as the concentration of NO3− was reduced, the anammox activity at 5 μM NO2− declined. In addition, as with all the previous experiments, there was a change in the relative significance of anammox to NO2− reduction on each occasion.

Modeling the behavior of anammox.

The model was run for the component forms (fp [equation 7] and fm [equation 8]) and the combined form of the biphasic anammox expression (fa [equation 6]), with the following parameters: ɛ = 0.15, lN = 2.5 μM, and Km = 2.5 μM. In addition, for each component and combined run, the proportion of anammox bacteria (θ) within the model was varied from 0.3 to 4.5%, and the results for the various scenarios are given in Fig. 4.

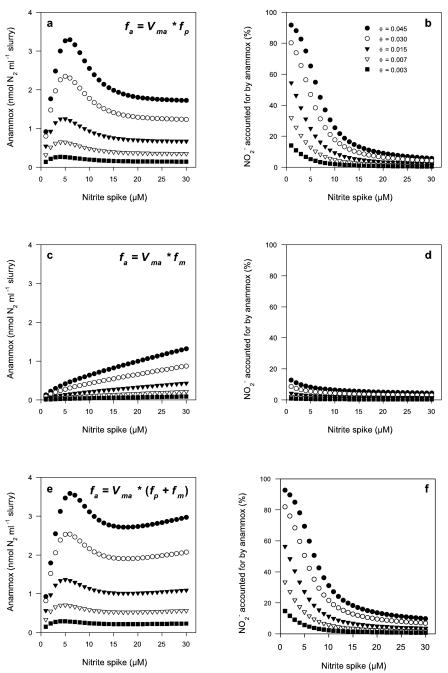

FIG. 4.

Model runs for anammox, with θ varying between 0.003 and 0.045 in each case. (a) Anammox as non-Michaelis fp (equation 7); (c) anammox as Michaelis fm (equation 8); (e) anammox as a function of the combined components fp + fm (equation 6). (b, d, and f) NO2− accounted for by anammox for each respective scenario (a, c, and e).

DISCUSSION

In our first study of anammox, we had demonstrated a linear response for anammox (production of 29N2) between 200 and 800 μM NO3− or NO2−, with a constant yield of 29N2 per molecule of NO3− or NO2− reduced (22). Here we have shown that this relationship holds for either acceptor down to a concentration of 10 μM but that below this level, anammox exhibits nonlinear behavior, with an optimum at 2 to 5 μM NO2−. Previous work with sediments had suggested that anammox has a Km for NO2− of 3 μM (4), and the results presented here confirm this observation. In single-enrichment trials with concentrations above 10 μM NO3−, anammox could account for approximately 1% of the reduced NO3−. This suggests that as more NO3− was added, a fixed proportion was lost as NO2− and, in turn, reduced via anammox, and hence the linear response (Fig. 1a and c). The flat response below 10 μM NO3− may have simply been due to the preferential affinity by anammox for the lower concentrations of NO2− resulting from NO3− reduction or, in part, to a disproportionately greater loss of NO2− from NO3− reduction below 10 μM NO3− (Fig. 1a). It has been suggested (12) that periplasmic NO3− reductase has a relatively high affinity (Nap; Km, 15 μM) and may enable bacteria to scavenge NO3− at low concentrations, while membrane-bound NO3− reductase (Nar; Km, 50 μM) is more suited to higher concentrations. Hence, a changing proportion of NO2− loss may reflect different enzyme systems, e.g., the loss of NO2− may be greater under Nap rather than Nar activity. The flat response below 10 μM NO2− indicates that the anammox community takes proportionately more of the available NO2− at lower concentrations, again reflecting the high affinity for NO2−. However, it is difficult to rationalize why the yield of anammox remained constant in the direct single presence of either NO2− or NO3− (Fig. 1a and c). In the single presence of NO2− the NO2− is obviously extracellular and thus directly available to the anammox community, yet the yield of anammox was the same as that for NO3− when the anammox community was reliant on a supply of NO2− originating from the NO3−-reducing community. For this to be the case, the availability of NO2− for anammox would have to be the same under both scenarios, either direct NO2− or NO3− reduced to NO2−. This suggests either that NO2− is never limiting in single-enrichment experiments or that some anammox bacteria may actually be coupled (both physically and metabolically) to members of the NO3−-reducing community and cannot proceed faster than the rate governed by the metabolism of the heterotrophic NO3− and NO2− reducers.

At a steady state in sediments, NO3− and NO2− coexist at concentrations separated by orders of magnitude, and it was only in the dual-enrichment experiments that the nonlinear behavior became fully apparent (Fig. 3). Clearly, the anammox activity was regulated by the presence of NO3−, and as the availability of NO3− was reduced, the anammox activity and its significance as a sink for NO2− declined (Fig. 3e and f). Hence, although anammox bacteria have a high affinity for NO2−, they are most likely vastly outnumbered by the heterotrophic NO3−- and NO2−-reducing community, which will reduce NO2− when NO3− is limiting (22). The final path of NO2− reduction is therefore modulated by the dual availability of NO3− and NO2− and the overall competition for electron acceptors. The data presented in Fig. 2 suggest that if the availability of NO3− is greater than that required for NO3− reductase to operate at Vmax, then NO2− is exported to the sediment, while below this it is not, explaining why the nonlinear behavior only became clearly visible when the loss of NO2− from NO3− reduction was controlled and NO2− was made available only under these controlled conditions. Despite the lack of NO2− leakage from NO3− reduction below 100 μM NO3−, anammox was always measurable in the single-enrichment experiments (Fig. 1), which again suggests that some of the anammox bacteria are tightly coupled to the turnover of NO3−. It is interesting that NO3− was reduced in these estuarine sediments (Thames) at 20 times the rate (∼100 μM h−1 compared to 5 μM h−1) of those in the Skagerrak, where anammox has also been measured (4, 19) and where its relative significance to N2 formation is much greater than that for the Thames. Assuming that NO3− reduction was operating at Vmax in the Skagerrak (4, 19), as shown for the Thames in Fig. 2b, then of the reduced NO3−, 60% accumulated as NO2− in the Skagerrak but only 20% accumulated as NO2− in the Thames. In the Skagerrak, therefore, the greater availability of NO2− from NO3− reduction may maintain a relatively large anammox population, and although the volume-specific rates of anammox are lower in the Skagerrak, its proportionate contribution to N2 production is greater than that in the Thames, where the anammox population is probably comparatively smaller. Whether this means that NO3− reduction leaks proportionately more NO2− in the Skagerrak than in the Thames or that NO3− respiration to NO2−, before anammox or denitrification, dominates the initial step of NO3− reduction is unclear.

In addition to the overall availability of NO2−- and NO3−-regulating anammox, there were marked fluctuations in anammox activity (Table 1). Seasonal effects have been clearly documented for the common forms of sediment metabolism, which usually follow smooth curves reflecting seasonal temperatures (6, 21). Short-term changes in sulfate reduction have been reported for upper estuarine sediments which corresponded with peaks in Desulfovibrio species activity (20). Although all of the experiments were carried out at 15°C and, hence, do not reflect in situ temperatures, the differences may reflect variations in the in situ abundance and/or activity of the anammox community sampled on each occasion; this is supported by the overall pattern of the data set and model output.

In our anammox model, NO2− can be reduced via either anammox or denitrification, with denitrification switching between NO2− or NO3− depending on the availability of NO3− ([NO3−]crit). Examples of the model output for anammox with the non-Michaelis (fp [equation 7]) (Fig. 4a and b), Michaelis (fm [equation 8]) (Fig. 4c and d), and combined (fp + fm [equation 6]) (Fig. 4e and f) components, with θ varying from 0.003 to 0.045, are given in Fig. 4. When fa includes only the function fp, anammox can never respond in a linear fashion at concentrations higher than 10 μM, since fp is modeled with a peak in activity when [NO2−] = lN and declines exponentially after this. Alternatively, a Michaelis function, such as fm, can never explain the nonlinear pattern shown at concentrations below 10 μM (Fig. 4c and d). It is only when the two functions are combined (as in equation 6) to give a biphasic behavior for anammox that the model begins to resemble the patterns observed in the data (compare Fig. 4e and f to Fig. 3c and d), in which the amount of anammox represents the sum of gas produced from both the Michaelis and non-Michaelis forms of the model. Whether or not there is a single anammox process with two enzyme systems or, alternatively, two independent anammox systems operating in these estuarine sediments is not known. The data suggest that in studies of anammox to date (19, 22), only the Michaelis form has been measured, which largely explains the previously reported linear production of 29N2 regardless of the concentration of NO2− or NO3− above 10 μM. The non-Michaelis form was certainly masked in our previous measurements of anammox (22), but it is not known whether this behavior would apply to off-shore continental shelf sediments (19). A Michaelis system may apply to anammox bacteria coupled tightly to the reduction of NO3−, and as such, NO2− will never be limiting and the operational range for NO2− is less significant. The non-Michaelis system could be optimized to function at actual pore-water NO2− concentrations, although the resolution of NO2− profiles and pore-water NO2− data to date are limited.

In addition to the biphasic expression, changing θ from 0.3 to 4.5% reproduced the range of anammox (amplitudes) measured in the slurry experiments (Fig. 4 e and f). Whether the effect of changing θ truly reflects a change in the in situ abundance (which may itself be a mixed population) or, alternatively, a change in specific activity is not known, as changing either in the model produces the same effect. Alternatively, the dampening down of anammox activity can be driven by increasing the rate of denitrification, yet this would seem least likely, as we consistently measured NO3− reduction at about 100 μM h−1 for these sediments, while the model would require an increase by a factor of about 8 to reproduce the minimum and maximum amplitudes shown in Fig. 4.

The production of 29N2 from labeled 15NH4+ and 14NO2− agrees with the 1:1 catabolism of 14NO2− + 15NH4+→29N2 + 2H2O. Anammox bacteria (in bioreactors) have, however, been shown to consume NH3 and NO2− with an overall stoichiometry of 1:1.3, with the excess NO2− (0.3 mol) being anaerobically oxidized to NO3−, though this ratio can change with the concentration of NO2− (16, 18). Hence, 1 mol of 29N2 accounts for 1 mol of 15NH4+ oxidized but potentially (depending on the actual sediment reaction) 1.3 mol of NO2− reduced, and therefore, the total anammox activity potentially needs to be multiplied by 1.3 to fully account for NO2− reduction via anammox. Allowing for this change in ratio, and depending on in situ conditions, anammox may account for the majority of NO2− reduction at 2 to 5 μM NO2− in these sediments.

The presence of anammox violates the central tenets of the isotope pairing technique (10), and the implications of this where anammox and denitrification coexist in sediments have been explored (15). Their discussion pivots around four assumptions, one of which is that anammox and denitrification are both limited by the supply of NO3− and that the uptake kinetics for its reduction product, NO2−, by denitrifying and anammox bacteria are similar. It is acknowledged that while the kinetics of denitrification as a function of NO3− are well characterized for sediments, little is known about the in situ regulation of anammox. The nonlinear response reported here for anammox below 10 μM NO2−, especially in the presence of NO3−, suggests that the kinetics of the two processes are different and challenges this assumption for anammox in estuarine sediments. In the presence of representative in situ NO2− and NO3− concentrations, the production of N2 via anammox increased. What regulates the proportionate significance of either anammox or denitrification to N2 formation in intact aquatic sediments is likely to be a combination of the respective availability of both NO3− and NO2− and the relative size or activity of the anammox population.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kevin J. Purdy for valuable discussions and Ian Sanders for field assistance.

This research was funded in part by a research grant (NER/A/S/2003/00354) to M.T. provided by the Natural Environment Research Council, United Kingdom.

REFERENCES

- 1.Betlach, M. R., and J. M. Tiedje. 1981. Kinetic explanation for accumulation of nitrite, nitric oxide and nitrous oxide during bacterial denitrification. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 42:1074-1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blaszczyk, M. 1993. Effect of medium composition on the denitrification of nitrate by Paracoccus denitrificans. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:3951-3953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dalsgaard, T., D. E. Canfield, J. Petersen, B. Thamdrup, and J. Acuna-González. 2003. N2 production by the anammox reaction in the anoxic water column of Golfo Dulce, Costa Rica. Nature 422:606-608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dalsgaard, T., and B. Thamdrup. 2002. Factors controlling anaerobic ammonium oxidation with nitrite in marine sediments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:3802-3808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dong, L. F., D. B. Nedwell, G. J. C. Underwood, D. C. O. Thornton, and I. Rusmana. 2002. Nitrous oxide formation in the Colne Estuary, England: the central role of nitrite. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:1240-1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jørgensen, B. B., and J. Sørensen. 1985. Seasonal cycles of O2, NO3− and SO42− reduction in estuarine sediments: the significance of an NO3− reduction maximum in spring. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 24:65-74. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kirkwood, D. S. 1996. Nutrients: practical notes on their determination in seawater. Techniques in marine environmental science no. 17. ICES, Copenhagen, Denmark.

- 8.Kuypers, M. M. M., A. O. Sliekers, G. Lavik, M. Schmid, B. B. Jørgensen, J. G. Kuenen, J. S. Sinninghe Damsté, M. Strous, and M. S. M. Jetten. 2003. Anaerobic ammonium oxidation by anammox bacteria in the Black Sea. Nature 422:608-611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nedwell, D. B., and M. Trimmer. 1996. Nitrogen fluxes through the upper estuary of the Great Ouse, England: the role of the bottom sediments. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 142:273-286. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nielsen, L. P. 1992. Denitrification in sediment determined from nitrogen isotope pairing. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 86:357-362. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nishio, T., I. Koike, and A. Hattori. 1982. Denitrification, nitrate reduction, and oxygen consumption in coastal and estuarine sediments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 43:648-653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Potter, L. C., P. Millington, L. Griffiths, G. H. Thomas, and J. A. Cole. 1999. Competition between Escherichia coli strains expressing either a periplasmic or a membrane-bound nitrate reductase: does Nap confer a selective advantage during nitrate-limited growth? Biochem. J. 344:77-84. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Revsbech, N. P., B. Madsen, and B. B. Jørgensen. 1986. Oxygen production and consumption in sediments determined at high spatial resolution by computer simulation of oxygen microelectrode data. Limnol. Oceanogr. 31:293-304. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Risgaard-Petersen, N., and K. Jensen. 1997. Nitrification and denitrification in the rhizosphere of the aquatic macrophyte Lobelia dortmanna L. Limnol. Oceanogr. 42:529-537. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Risgaard-Petersen, N., L. P. Nielsen, S. Rysgaard, T. Dalsgaard, and R. L. Meyer. 2003. Application of the isotope pairing technique in sediments where anammox and denitrification coexist. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods 1:63-73. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schmidt, I., A. O. Sliekers, M. Schmid, E. Bock, J. Fuerst, J. G. Kuenen, M. S. M. Jetten, and M. Strous. 2003. New concepts of microbial treatment processes for nitrogen removal in wastewater. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 27:481-492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steif, P., D. De Beer, and D. Neumann. 2002. Small-scale distribution of interstitial nitrite in freshwater sediment microcosms: the role of nitrate and oxygen availability, and sediment permeability. Microbiol. Ecol. 43:367-378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Strous, M., J. G. Kuenen, and M. S. M. Jetten. 1999. Key physiology of anaerobic ammonium oxidation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:3248-3250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thamdrup, B., and T. Dalsgaard. 2002. Production of N2 through anaerobic ammonium oxidation coupled to nitrate reduction in marine sediments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:1312-1318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trimmer, M., K. J. Purdy, and D. B. Nedwell. 1997. Process measurement and phylogenetic analysis of the sulphate reducing bacterial communities of two contrasting benthic sites in the upper estuary of the Great Ouse, Norfolk, U.K. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 24:333-342. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trimmer, M., D. B. Nedwell, D. Sivyer, and S. J. Malcolm. 1998. Nitrogen fluxes through the lower estuary of the Great Ouse, England: the role of the bottom sediments. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 163:109-124. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trimmer, M., J. C. Nicholls, and B. Deflandre. 2003. Anaerobic ammonium oxidation measured in sediments along the Thames Estuary, United Kingdom. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:6447-6454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]